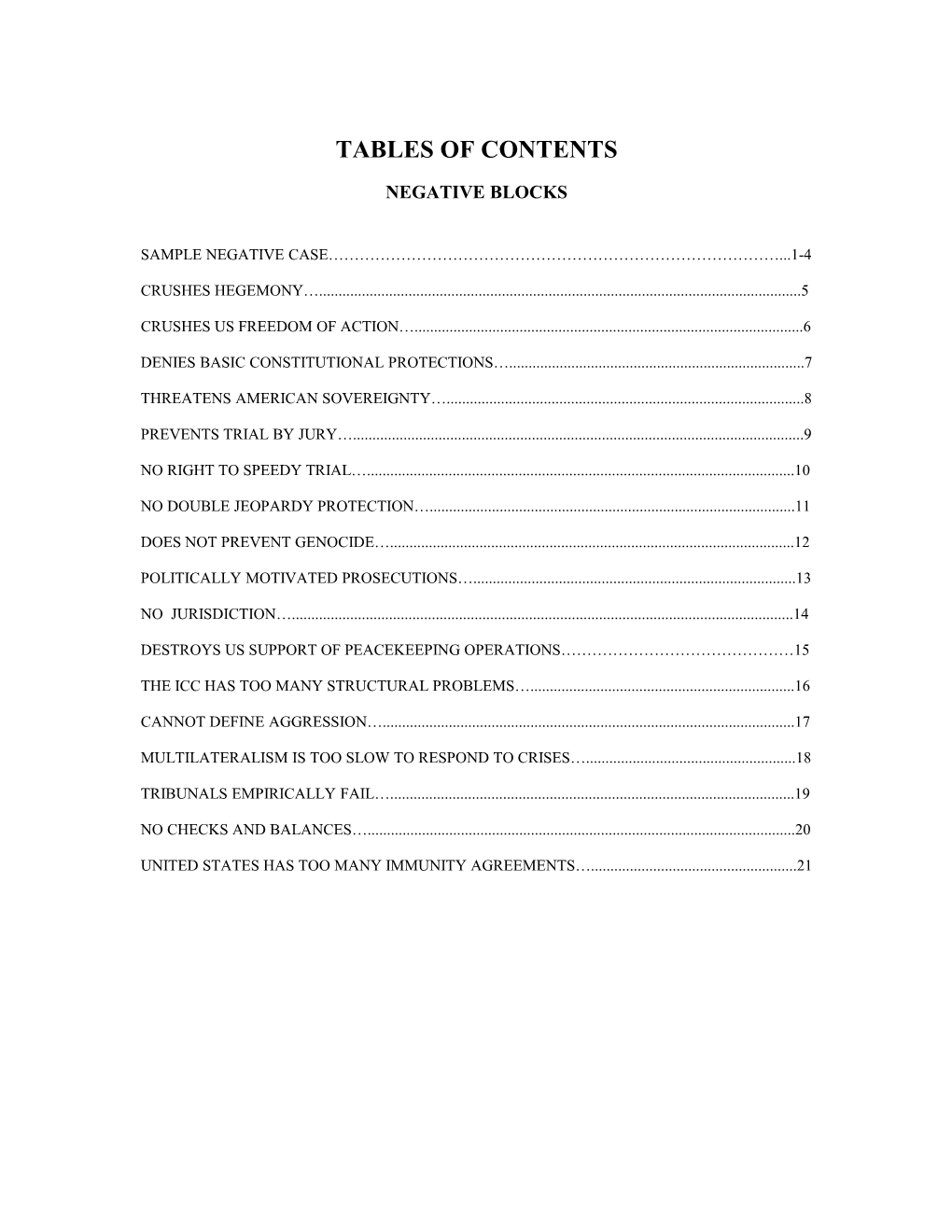

TABLES OF CONTENTS

NEGATIVE BLOCKS

SAMPLE NEGATIVE CASE……………………………………………………………………………...1-4

CRUSHES HEGEMONY…...... 5

CRUSHES US FREEDOM OF ACTION…...... 6

DENIES BASIC CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTIONS…...... 7

THREATENS AMERICAN SOVEREIGNTY…...... 8

PREVENTS TRIAL BY JURY…...... 9

NO RIGHT TO SPEEDY TRIAL…...... 10

NO DOUBLE JEOPARDY PROTECTION…...... 11

DOES NOT PREVENT GENOCIDE…...... 12

POLITICALLY MOTIVATED PROSECUTIONS…...... 13

NO JURISDICTION…...... 14

DESTROYS US SUPPORT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS………………………………………15

THE ICC HAS TOO MANY STRUCTURAL PROBLEMS…...... 16

CANNOT DEFINE AGGRESSION…...... 17

MULTILATERALISM IS TOO SLOW TO RESPOND TO CRISES…...... 18

TRIBUNALS EMPIRICALLY FAIL…...... 19

NO CHECKS AND BALANCES…...... 20

UNITED STATES HAS TOO MANY IMMUNITY AGREEMENTS…...... 21 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen. Let’s get right to the issues at hand. Today we debate the resolution: Resolved: The United States ought to submit to the jurisdiction of an international court designed to prosecute crimes against humanity. I will begin by presenting definitions, value, and criteria before going through several contentions.

My definitions for this round are:

Ought refers to having a specific obligation or duty to take some form of action.

Submit means to relegate or refer to another person for decision or judgment.

Jurisdiction means that practical authority is granted to a formally constituted legal body or to a political leader to deal with and make pronouncements on legal matters and, by implication, to administer justice.

International courts are formed by treaties between nations, or under the authority of an international organization such as the United Nations.

Prosecute means to initiate and carry out a legal action, usually associated with carrying out a criminal case.

Crimes against humanity, according to the International Criminal Court, include crimes such as the extermination of civilians, enslavement, torture, rape, forced pregnancy, deportation, persecution on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious or gender grounds, and enforced disappearances—but only when they are part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population.

VALUE: SOVEREIGNTY My value today is sovereignty, defined as the power to do everything in a state without accountability. This sense of sovereignty provides for complete control of judicial powers within the nation state. Sovereignty implies a sense of equality of peoples that universality can be applied to each individual nation state.

CRITERION: UTILITARIANISM My criterion for this debate, must therefore, be that of utilitarianism defined as the greatest good for the greatest number. Only utilitarianism clearly achieves the intended goal of treating and valuing all people equally and therefore putting everyone’s risks and stakes in an equal place. Based off this criteria and value we would like to prevent several advantages.

CONTENTION ONE: ANY INTERNATIONAL COURT WOULD CRUSH UNITED STATES MILITARY HEGEMONY.

SUBPOINT A: THE ICC KILLS US FREEDOM OF ACTION- IT WOULD OUTLAW PREEMPTIVE STRIKES INTENDED TO PROTECT OUR OWN NATIONAL SECURITY Gary Dempsey, Foreign Policy Analyst at the Cato Institute, August 19, 1998, Courting Disaster, The Cato Institute, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.cato.org/dailys/8-19-98.html More worrisome still is the inclusion of the yet-to-be-defined crime of "aggression" in the court's expansive jurisdiction. According to the Rome debates, "aggression" could eventually include such things as the "bombardment by the armed forces of a State against the territory of another State" and "the blockade of the ports or coasts of a State by the armed forces of another State." Including those actions under "aggression" will reduce the military options available to the United States by outlawing preemptive strikes and the kind of naval blockade President Kennedy employed during the Cuban Missile Crisis. That has U.S. policymakers worried. As Department of Defense spokesman Kenneth Bacon has explained, "What we're concerned about is that the court not be set up in a way that gives it very broad authority to pursue a vague definition of aggression that could be confused with legitimate defensive action to protect our national security interests."

2 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

SUBPOINT B: THE ICC RESTRICTS US FREEDOM OF ACTION- EMPIRICALLY PROVEN BY THE AIR CAMPAIGN IN YUGOSLAVIA John R. Bolton, Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, January 18, 2000, Flaws Undermine Concept: Would Court Would be Ineffective, Threaten U.S. Powers, The American Enterprise Institute, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.aei.org/news/newsID.11201,filter./news_detail.asp Second, restraining U.S. military power is the real hidden agenda here. Already Mary Robinson, the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, accused NATO of acting illegally in the air campaign against Yugoslavia -- a precursor of things to come. Moreover, creating potentially powerful institutions outside of, and purportedly superior to, our Constitution is inconsistent with U.S. autonomy and will erode our ability to act independently in our interests. Not only is the court potentially threatening, it also establishes a dangerous precedent.

CONTENTION TWO: THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT HAS PROVEN THAT IT DOES NOT PROTECT THE RIGHTS GUARANTEED TO UNITED STATES CITIZENS IN THE CONSTITUTION

SUBPOINT A: THE ICC VIOLATES THE BASIC PRINCIPLES OF AMERICA- THE CONSTITUION SEEKS TO PROTECT AMERICANS FROM PROSECUTION BY FOREIGN POWERS Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivikin Jr., Attorneys at Hunton and Williams, February 5, 1999, The International Criminal Court vs. the American People, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/BG1249.cfm These provisions referred to the British practice of prosecuting Americans in "vice-admiralty" courts for criminal violations of the navigation and trade laws. Like the ICC, these courts followed the civil law, "inquisitorial" system. 14 Convictions, of course, could be obtained far more easily from these tribunals than from uncooperative colonial juries. 15 The U.S. Constitution's Framers sought to eliminate forever the danger that Americans might again be surrendered to a foreign power for trial by specifically requiring that criminal trials be by jury and conducted in the state and district where the crime was committed. This is the only right guaranteed by the Constitution to be stated twice in the original document and its first ten amendments. As Justice Joseph Story explained, the "object" of these provisions was "to secure the party accused from being dragged to a trial in some distant state, away from his friends, and witnesses, and neighborhood; and thus subjected to the verdict of mere strangers, who may feel no common sympathy, or who may even cherish animosities, or prejudices against him." 16

SUBPOINT B: US PARTICIPATION IN THE ICC IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL BECAUSE IT DOES NOT ALLOW PROTECTIONS GUARANTEED BY THE CONSTITUTION Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivikin Jr., Attorneys at Hunton and Williams, February 5, 1999, The International Criminal Court vs. the American People, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/BG1249.cfm The ICC violates constitutional principles. The failure of the ICC treaty to adopt the minimum guarantees of the U.S. Constitution's Bill of Rights is, in fact, one of the principal reasons why the United States could not, even if it wanted to, join the ICC treaty regime. As the U.S. Supreme Court recently suggested in United States v. Balsys, 10 the United States cannot participate in or facilitate a criminal trial under its own authority, even in part, unless the Constitution's guarantees are preserved. If, however, the United States were to join the ICC treaty regime, the prosecutions undertaken by the court, whether involving the actions of Americans in the United States or overseas, would be "as much on behalf of the United States as of" any other State Party. 11 Since the guarantees of the Bill of Rights would not be available in the ICC, the United States could not participate in, or facilitate, any such court.

3 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

CONTENTION THREE: THE ICC HAS NO LEGITIMATE AUTHORITY AND THREATENS AMERICAN SOVEREIGNTY

SUBPOINT A: THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT THREATENS OUR SOVEREIGNTY BY ASSERTING ITS JURISDICTION TO TRY OUR CITIZENS WITHOUT THE CONSENT OF OUR ELECTED BODIES Marc Grossman, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, May 6, 2002, American Foreign Policy and the International Criminal Court, Congressional Information Services, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N Third, the treaty threatens the sovereignty of the United States. The Court, as constituted today, claims the authority to detain and try American citizens, even through our democratically-elected representatives have not agreed to be bound by the treaty. While sovereign nations have the authority to try non-citizens who have committed crimes against their citizens or in their territory, the United States has never recognized the right of an international organization to do so absent consent or a UN Security Council mandate.

SUBPOINT B: THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT ASSERTS IT’S JURISDICTION EVEN WHEN SIGNATORY STATES DO NOT WANT IT TO BE, AND DOES NOT NEED THE APPROVAL OF THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL Jeremy Rabkin, Professor of Government at Cornell University, October 1998, Courting Disaster International Law: Yes International Criminal Court No, The America Spectator, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N The State Department sought to get by these fundamental problems by tying the court to the Security Council--where the United States has an absolute veto under the terms of the U.N. Charter. If the court could only be invoked by the Security Council, then the United States could block any action against American citizens or any action that would create a ticklish problem for American diplomacy. But the Rome conference insisted on a court that would have its own independent prosecutorial arm, acting on its own initiative. The court's jurisdiction is limited to cases involving signatory states--but its jurisdiction may be invoked even when the signatory state does not want it to be, to protect nationals of a signatory state even when the perpetrators are not from a signatory state. Even when the criminal's home state initiates prosecution in its own courts, the international court may launch a subsequent prosecution if it deems the original trial (or sanction) inadequate. If the court were up and running and Sudan were a party, the court could prosecute U.S. officials responsible for the cruise missile attack on a pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum.

4 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

CRUSHES HEGEMONY

1. UNITED STATES HEGEMONY IS HIGH NOW. Zbigniew Brzenzinski, Former National Security Adviser to Jimmy Carter, 2004, The Choice: Global Domination or Global Leadership, pg. viii At the outset of the twenty-first century, America’s power is unprecedented in its global military reach, in the centrality of America’s economic vitality for the well-being of the world economy, in the innovative impact of America’s technological dynamism, and in the worldwide appeal of the multifaceted and often crass American mass culture. All of these give America matchless global political clout. For better or worse, America is the global pacesetter, and there is no rival in sight.

2. INTERNATIONAL COURTS WILL DESTROY UNITED STATES HEGEMONY BY LIMITING OUR FREEDOM OF ACTION- IT WILL REQUIRE US TO ASK PERMISSION FROM THE UN EVERY TIME WE WISH TO INTERVENE. Brett D. Schaefer, Fellow in International Regulatory Affairs, July 2, 1998, The International Criminal Court: Threatening U.S. Sovereignty and Security, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/EM537.cfm The ICC also presents important policy concerns on U.S. national security and the use of the U.S. military. For example, many countries support placing the "crime of aggression" under the jurisdiction of an ICC. Several definitions of "crime of aggression" are being debated; all are variations of the phrasing known as Option 1, which states that any individual in a position of "exercising control or capable of directing, planning, preparing, ordering, initiating, or carrying out an armed attack" against another state, when this attack is in contravention of the U.N. Charter, is subject to investigation, trial, conviction, and punishment by the ICC. In effect, this would require the United States to receive prior U.N. Security Council approval and ICC confirmation of the legality of a proposed military action. If it does not do so, every U.S. official involved in the operation, up to and including the President, could be charged, tried, convicted, and sentenced merely for protecting U.S. interests.

3. A LOSS OF UNITED STATES HEGEMONY WILL CAUSE MULTIPLE NUCLEAR WARS, SPREADING DISEASE AND COLLAPSING THE GLOBAL ECONOMY. Niall Fergusson, Herzog Professor of History at NYU, July/August 2004, A World Without Power, Foreign Policy, online L/N

The worst effects of the new Dark Age would be felt on the edges of the waning great powers. The wealthiest ports of the global economy--from New York to Rotterdam to Shanghai--would become the targets of plunderers and pirates. With ease, terrorists could disrupt the freedom of the seas, targeting oil tankers, aircraft carriers, and cruise liners, while Western nations frantically concentrated on making their airports secure. Meanwhile, limited nuclear wars could devastate numerous regions, beginning in the Korean peninsula and Kashmir, perhaps ending catastrophically in the Middle East. In Latin America, wretchedly poor citizens would seek solace in Evangelical Christianity imported by U.S. religious orders. In Africa, the great plagues of aids and malaria would continue their deadly work. The few remaining solvent airlines would simply suspend services to many cities in these continents; who would wish to leave their privately guarded safe havens to go there? For all these reasons, the prospect of an apolar world should frighten us today a great deal more than it frightened the heirs of Charlemagne. If the United States retreats from global hegemony--its fragile self- image dented by minor setbacks on the imperial frontier-its critics at home and abroad must not pretend that they are ushering in a new era of multipolar harmony, or even a return to the good old balance of power. Be careful what you wish for. The alternative to unipolarity would not be multipolarity at all. It would be apolarity-a global vacuum of power. And far more dangerous forces than rival great powers would benefit from such a not-so-new world disorder.

5 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

CRUSHES US FREEDOM OF ACTION

1. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT KILLS US ABILITY TO ACT AGAINST THREATS- IF THE ICC THOUGHT US ACTION WAS AGGRESSIVE IT COULD TAKE THE PRESIDENT INTO ITS JURISDICTION. Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivikin Jr., Attorneys at Hunton and Williams, February 5, 1999, The International Criminal Court vs. the American People, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/BG1249.cfm The ICC threatens America's ability to defend its interests through military action. The ICC would be able to prosecute any individual American, including the President, military and civilian officers and officials, enlisted personnel, and even ordinary citizens who were involved in any action it determined to be unlawful and within its jurisdiction. For example, if the ICC existed today, it could investigate President Clinton's August 1998 attack on Osama bin Laden's terrorist base in Afghanistan or the more recent attacks on Iraq. Possible allegations would be that these attacks constituted "aggression" or crimes against humanity based upon any resultant damage to civilians or civilian property. If the ICC determined that there was sufficient evidence to support an indictment, the President, the Secretary of Defense, or any other individual who took part in planning or executing the attacks could be sought by the ICC to be tried for these actions, even though they were entirely lawful under the Constitution and laws of the United States.

2. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT PREVENTS FORWARD DEPLOYMENT OF US FORCES BY PLACING THOSE DECISIONS IN THE HANDS OF THE JUDGES. Marc Grossman, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, May 6, 2002, American Foreign Policy and the International Criminal Court, Congressional Information Services, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N Fourth, the current structure of the International Criminal Court undermines the democratic rights of our people and could erode the fundamental elements of the United Nations Charter, specifically the right to self defense. With the ICC prosecutor and judges presuming to sit in judgment of the security decisions of States without their assent, the ICC could have a chilling effect on the willingness of States to project power in defense of their moral and security interests. This power must sometimes be projected. The principled projection of force by the world's democracies is critical to protecting human rights--to stopping genocide or changing regimes like the Taliban, which abuse their people and promote terror against the world.

3. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT KILLS US FREEDOM OF ACTION BECAUSE IT IS TOO RISKY TO PUT OUR TROOPS WITHIN THE GRASP OF ICC JURISDICTION. Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivikin Jr., Attorneys at Hunton and Williams, February 5, 1999, The International Criminal Court vs. the American People, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/BG1249.cfm Make plain that a country's ratification of the ICC treaty will result in a reassessment of U.S. troop deployments in that country. The United States should not contemplate a policy of isolation, nor should it withdraw U.S. troops from strategically important deployments. Such a policy would not be in its long- term interests. However, the United States should inform countries in which U.S. troops are stationed that ratification of the ICC would present a direct threat to U.S. soldiers stationed within their borders and, therefore, would require a reassessment of the terms and conditions of its U.S. overseas troop deployments. Tens of thousands American service men and women are stationed overseas, principally in Western Europe, but also in the Persian Gulf and Asia, and their presence is in the interests of the United States and the host states as well. Many of these hosts rely upon U.S. military power to guarantee their security and stability. It should be made clear to these states that part of the price they must pay for such protection, which allows them to eschew much of the defense spending that otherwise would be required to ensure their security, is the guarantee that they will not subject U.S. nationals to the ICC's jurisdiction.

6 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

DENIES BASIC CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTIONS

1. THE ICC IS A MOCKERY OF CIVIL LIBERTIES- EVEN THE MOST BASIC RIGHTS GUARANTEED WOULD NOT BE GIVEN TO DEFENDANTS. Ted Galen Carpenter, VP for Foreign Policy Studies at The Cato Institute, December 27, 2000, No Civil Liberties at the International Criminal Court, The Cato Institute, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.cato.org/dailys/12-27-00.html The Criminal Court is a horrific institution from the standpoint of civil liberties. It would make a mockery of even the most basic due process guarantees. We have already had a glimpse of the probable abuses from the operation of the ICC's predecessors, the special war crimes tribunals in the Balkans and Rwanda. Rights that Americans take for granted would be greatly diluted or absent entirely in ICC trials. For example, there is no right to a trial by an impartial jury. A verdict is rendered by majority vote of a panel of appointed judges. Thus, a 3-2 vote could doom a defendant to a lengthy prison term -- in some cases even a life term. If that were not bad enough, some -- perhaps all -- of the judges on a panel might come from countries where there is no concept of an independent judiciary or a tradition of fair trials. A defendant could even face jurists who were officials in regimes that were openly biased against his government or political movement. It gets worse. There is no protection against double jeopardy. If a defendant is acquitted of charges, the prosecutor's office can appeal the verdict to an appellate body within the ICC. A hapless defendant could be subjected to prosecution for the same offense again, and again, and again. Nor is there any guarantee of either a speedy or a public trial. The Court could hold indicted individuals for months or even years before judicial proceedings get underway. The Yugoslavia war crimes tribunal has held sessions behind closed doors—supposedly to protect the privacy of alleged victims of war crimes. Such nonpublic sessions underscore perhaps the worst feature of the ICC.

2. US PARTICIPATION IN THE ICC IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL BECAUSE IT DOES NOT ALLOW PROTECTIONS GUARANTEED BY THE CONSTITUTION Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivikin Jr., Attorneys at Hunton and Williams, February 5, 1999, The International Criminal Court vs. the American People, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/BG1249.cfm The ICC violates constitutional principles. The failure of the ICC treaty to adopt the minimum guarantees of the U.S. Constitution's Bill of Rights is, in fact, one of the principal reasons why the United States could not, even if it wanted to, join the ICC treaty regime. As the U.S. Supreme Court recently suggested in United States v. Balsys, 10 the United States cannot participate in or facilitate a criminal trial under its own authority, even in part, unless the Constitution's guarantees are preserved. If, however, the United States were to join the ICC treaty regime, the prosecutions undertaken by the court, whether involving the actions of Americans in the United States or overseas, would be "as much on behalf of the United States as of" any other State Party. 11 Since the guarantees of the Bill of Rights would not be available in the ICC, the United States could not participate in, or facilitate, any such court.

3. ICC IS UNCONSTITUTIONAL BECAUSE IT ALLOWS CRIMES COMMITTED IN THE UNITED STATES TO BE TRIED AT THE ICC. Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivikin Jr., Attorneys at Hunton and Williams, February 5, 1999, The International Criminal Court vs. the American People, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/BG1249.cfm United States participation in the ICC treaty regime would also be unconstitutional because it would allow the trial of American citizens for crimes committed on American soil, which are otherwise entirely within the judicial power of the United States. The Supreme Court has long held that only the courts of the United States, as established under the Constitution, can try such offenses. The Supreme Court made this clear in the landmark Civil War case of Ex parte Milligan. In that case, the Court reversed a civilian's conviction in a military tribunal, which did not provide the guarantees of the Bill of Rights, holding that "[e]very trial involves the exercise of judicial power," and that the military court in question could exercise "no part of the judicial power of the country." 12 This reasoning is equally applicable to the ICC.

7 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

THREATENS AMERICAN SOVEREIGNTY

1. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT THREATENS AMERICAN SOVEREIGNTY BECAUSE IT SHARES OUR POWERS WITH THE COURT Jeremy Rabkin, Professor of Government at Cornell University, October 1998, Courting Disaster International Law: Yes International Criminal Court No, The America Spectator, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N If the International Criminal Court is constitutional, then it would seem entirely constitutional to make wholesale transfers of the constitutional authority of U.S. institutions to international bodies. In fact, the countries of the European Union have done something much like this, allowing appeals from their own courts to the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg. They have also delegated legislative and regulatory powers from their own parliaments and governments to European institutions. If the U. S. can do the same sort of thing by treaty, then we have a different constitution than we thought we did--one whose basic allocation of powers and responsibilities can be rearranged whenever the president (and Senate) agrees with one or more foreign governments to do so. The International Criminal Court, of course, is supposed to involve more than two or three other countries. It is supposed to be an institution for the world, a new pillar of international law. But for just that reason it raises a second set of disturbing issues. The Framers of the U.S. Constitution were not contemptuous of international law. Among other things, they specified that Congress should have power to "punish offenses against the law of nations"--on the understanding that an independent United States should take seriously its obligation to enforce the "law of nations" (as international law was called in that era). But the understanding of the Framers (and of all subsequent statesmen until recently) was that international law governed the relations of sovereign states. Sovereign states do not share their internal governing authority with international bodies. And they cannot act as obedient subjects of some higher authority and still claim to be sovereign. For this reason, international law has always been understood as a special kind of law, since it lacks the force of a central authority to enforce it.

2. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT THREATENS AMERICAN SOVEREIGNTY- NO LONGER WILL AMERICAN OFFICIALS BE ANSWERABLE TO AMERICANS, BUT RATHER TO AN INTERNATIONAL COURT. Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivikin Jr., Attorneys at Hunton and Williams, February 5, 1999, The International Criminal Court vs. the American People, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/BG1249.cfm The ICC threatens American self-government. The creation of a permanent, supranational court with the independent power to judge and punish elected officials for their official actions represents a decisive break with fundamental American ideals of self-government and popular sovereignty. It would constitute the transfer of the ultimate authority to judge the acts of U.S. officials away from the American people to an unelected and unaccountable international bureaucracy. As Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in his Democracy in America, "[h]e who punishes the criminal is . . .the real master of society." In this regard, the claims of ICC supporters that the court is not directed at American citizens may be dismissed. Suggestions that U.S. soldiers and civilians could not be brought before the ICC because that court would be required to defer to U.S. judicial processes--the concept of "complementarity"--are disingenuous. Under the ICC treaty, the court would be the absolute judge of its own jurisdiction and would itself determine when, if ever, such a deferral was appropriate.

3. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT THREATENS OUR SOVEREIGNTY BY ASSERTING ITS JURISDICTION TO TRY OUR CITIZENS WITHOUT THE CONSENT OF OUR ELECTED BODIES Marc Grossman, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, May 6, 2002, American Foreign Policy and the International Criminal Court, Congressional Information Services, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N Third, the treaty threatens the sovereignty of the United States. The Court, as constituted today, claims the authority to detain and try American citizens, even through our democratically-elected representatives have not agreed to be bound by the treaty. While sovereign nations have the authority to try non-citizens who have committed crimes against their citizens or in their territory, the United States has never recognized the right of an international organization to do so absent consent or a UN Security Council mandate.

8 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

ICC BAD: PREVENTS TRIAL BY JURY

1. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT DOES NOT GUARANTEE A RIGHT TO TRIAL BY JURY Brett D. Schaefer, Fellow in International Regulatory Affairs, July 2, 1998, The International Criminal Court: Threatening U.S. Sovereignty and Security, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/EM537.cfm The United States also faces unique problems with the very nature of an ICC. It is questionable, for example, whether the U.S. Constitution allows the U.S. government to permit U.S. citizens to be tried for alleged crimes committed on U.S. soil by a body that is not a court of the United States. For example, if the United States agreed to grant jurisdiction over international drug trafficking to the ICC, this court legitimately could demand extradition of an accused U.S. citizen who never set foot outside the United States. Another problem is that the ICC most likely would not provide many of the basic legal rights of Americans, such as a trial by jury, forbidding trials in absentia, and the right of the accused to confront his accuser.

2. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT DOES NOT GUARANTEE A RIGHT TO TRIAL BY JURY Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivikin Jr., Attorneys at Hunton and Williams, February 5, 1999, The International Criminal Court vs. the American People, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/BG1249.cfm The ICC is fundamentally inconsistent with American tradition and law. In its design and operation, the ICC is fundamentally inconsistent with core American political and legal values. Indeed, if Americans ever were arraigned before the ICC, they would face a judicial process almost entirely foreign to the traditions and standards of the United States. First and foremost, they would face a civil law "inquisitorial" system where guilt would be determined by judges (possibly from countries hostile to the United States) alone. There would be no right to trial by jury, a right considered so central by the Founders of the American Republic that it was guaranteed twice in the U.S. Constitution (in Article III, Section 2, and the Sixth Amendment).

3. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT DOES NOT GUARANTEE A RIGHT TO TRIAL BY JURY Ted Galen Carpenter, VP for Foreign Policy Studies at The Cato Institute, December 27, 2000, No Civil Liberties at the International Criminal Court, The Cato Institute, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.cato.org/dailys/12-27-00.html Rights that Americans take for granted would be greatly diluted or absent entirely in ICC trials. For example, there is no right to a trial by an impartial jury. A verdict is rendered by majority vote of a panel of appointed judges. Thus, a 3-2 vote could doom a defendant to a lengthy prison term -- in some cases even a life term. If that were not bad enough, some -- perhaps all -- of the judges on a panel might come from countries where there is no concept of an independent judiciary or a tradition of fair trials. A defendant could even face jurists who were officials in regimes that were openly biased against his government or political movement.

4. THE ICC FORBIDS TRIALS BY JURY Gary Dempsey, Foreign Policy Analyst at the Cato Institute, August 19, 1998, Courting Disaster, The Cato Institute, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.cato.org/dailys/8-19-98.html Specifically, the court threatens to diminish America's sovereignty, produce arbitrary and highly politicized "justice," and grow into a jurisdictional leviathan. Already some supporters of the proposed court want to give it the authority to prosecute drug trafficking as well as such vague offenses as "serious threats to the environment" and "committing outrages on personal dignity." Even if such expansive authority is not given to the ICC initially, the potential for jurisdictional creep is considerable and worrisome. Moreover, it appears that many of the legal safeguards American citizens enjoy under the U.S. Constitution would be suspended if they were brought before the court. Endangered constitutional protections include the prohibition against double jeopardy, the right to trial by an impartial jury, and the right of the accused to confront the witnesses against him.

9 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

ICC BAD: NO RIGHT TO SPEEDY TRIAL

1. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT DOES NOT GUARANTEE A RIGHT TO A SPEEDY TRIAL- THEY VIEW ANYWHERE BETWEEN 1-5 YEARS AS BEING JUST. Robert Brickman, Independent Writer, May 2003, A Court Without Laws, Brandeis Univeristy Publication, accessed 12/10/2008, http://people.brandeis.edu/~cbmag/Articles/2003%20May/A%20court%20without %20laws-%20May%202003.pdf All these fears aside, the ICC fundamentally and explicitly violates the Constitution. Were a United States citizen to be brought before the ICC, he would not have the rights secured by the Bill of Rights that many in this country take for granted. The right to a speedy trial, for instance, would not necessarily be applied in the ICC. Though the Court’s bylaws say that defendants shall be tried without “undue delay,” Hague prosecutors for the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia have stated that anywhere from one to five years is not considered undue delay. This practice clearly mocks the systematic presumption of innocence which remain an integral part in the trial of an American. In the U.S., a prisoner cannot simply be held without trial. If a federal defendant is not brought before a jury in three months, he must be released. Other inconsistencies such as the right to a jury trial, the right to face one’s accuser, the ban of double jeopardy and the inadmissibility of hearsay evidence all point to one larger problem: by ratifying the Rome Statute and becoming party to the ICC, the citizens of the United States relinquish a portion of their inalienable rights.

2. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT DOES NOT GUARANTEE A RIGHT TO A SPEEDY TRIAL Lee A. Casey and David B. Rivikin Jr., Attorneys at Hunton and Williams, February 5, 1999, The International Criminal Court vs. the American People, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/BG1249.cfm Trial by jury is not, of course, the only right guaranteed to Americans that would be unavailable in an ICC. For example, an American surrendered to the ICC would not enjoy rights to reasonable bail or a speedy trial, as those rights are known and guaranteed in the United States. Although the ICC would have to provide a trial "without undue delay," this could mean many years in prison. For instance, mocking the presumption of innocence, the prosecutor of the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, a court widely viewed as a model for the ICC, actually argued that up to five years would not be too long to wait in prison for a trial. 8

3. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT DOES NOT GUARANTEE THE RIGHTS TO A SPEEDY TRIAL. The American Cause, May 21, 2001, International Court: Guilty on All Counts, The American Cause, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.theamericancause.org/intl.htm This morning, the New York Times writes a matter-of-fact obituary for liberty lost: "The international criminal court is going to be a reality…The Bush Administration … should … not waste global influence in a futile attempt to prevent the court’s establishment." Not so fast. The Times forgets that the present occupant of 1600 Penn withdrew from the ill-conceived Kyoto protocol in a weekend. Under the Vienna Convention, he can redeem his predecessor’s folly by submitting a letter of declaration asking to be released, for though we have signed on, we have not ratified the Rome Treaty. As things now stand, the treaty has been signed by 139 nations and ratified by 31. Once 60 countries ratify, the court will be empowered to subpoena anyone anywhere in the world, and signatory states will be obligated to apprehend the accused who will be tried and sentenced before UN judges. Subjecting our citizens to this regime would be unconstitutional both in establishment and application. In 1866, the Supreme Court ruled that a court not authorized under Article III of our Constitution could have "no part of the judicial power of the country." Moreover, the traditional tenets of American justice – a speedy trial, the right to confront witnesses, innocent until proven guilty – are not likely to be projected by global dimensions as long as our fellow signatories include such anti-democratic exemplars as Algeria, Cambodia, Haiti, Iran, and Sudan.

ICC BAD: NO DOUBLE JEOPARDY PROTECTIONS

10 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

1. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT DOES NOT OFFER PROTECTIONS AGAINST DOUBLE JEOPARDY. David Storobin, J.D. Rutgers University School of Law, June 13, 2005, International Criminal Court: Guilty as Charged, The Global Politician, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.globalpolitician.com/2875-icc- courts The Fifth Amendment further states: "No person shall . . . be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb." The ICC also doesn't recognizes this right. Indeed, by virtue of allowing the ICC to re-try individuals who were already tried by national courts (after ICC found the process "ineffective"), it in and of itself creates the problem of double jeopardy. That is especially so considering that the court seeks to be complimentary to the national courts. Even if this problem can be solved, however, it remains a fact that people can be tried again and again in the ICC until the prosecutor and the alleged victims get the desired result. And even if a conviction never results, one can easily understand how a person can be terrorized - financially, emotionally and otherwise - throughout his life by being tried again and again for the same crime. According to "Protection of United States Troops From Foreign Prosecution Act of 1999": "A prosecutor under the ICC Treaty would be able to appeal a verdict of acquittal, effectively placing the accused in `double jeopardy' . . . . Such appeals are forbidden in the law of the United States and have been inconsistent with the Anglo-American legal tradition since the 17th century." [8]

2. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT DOES NOT PROVIDE PROTECTIONS AGAINST DOUBLE JEOPARDY Michael S. Rozeff, Professor of Finance at the University of Buffalo, July 12, 2002, To Back the International Criminal Court or Not, Lew Rockwell, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.lewrockwell.com/rozeff/rozeff43.html This power means that the Court can open a case if it and it alone decides that a State trial is shielding a defendant, delaying trial to shield a person, or simply not proceeding independently and impartially. The member States have created in the ICC a kind of supreme court that does not have to wait for cases to be brought to it but that can preempt ongoing proceedings or start new trials after trials in national courts have already occurred. The member States have therefore given up significant sovereignty, although any State can withdraw upon one year’s notice. But taking a case out of a national court might cause that nation to withdraw from the Court or incite others to withdraw, or they might try to amend the Statute. These actions might politically restrain the Court. They might make the Court weaker than Article 17 makes it seem. Conversely, some nations (rulers) might welcome the opportunity to shift a troublesome case to the ICC. However this works out, Article 17 alters due process for the affected citizens. It allows legal double jeopardy or being tried twice for the same crime. Double jeopardy could occur even in a private justice system or under anarchy. However, the incentives do not favor it because it creates costly conflicts among courts, and courts bear these costs directly. In the case of the ICC, we can’t be sure how this will play out or whether the Court will ever invoke Article 17.

3. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT DOES NOT PROVIDE PROTECTIONS AGAINST DOUBLE JEOPARDY. Earl Taylor Jr., August 1998, Newsletter, The National Center for Constitutional Studies, accessed 12/10/2008, https://www.nccs.net/newsletter/aug98nl_print.html Many nations did not want the definitional elements of the various international crimes to be included in the text of the statute. This presents the legal enigma of preventing a person from knowing what behavior constitutes a crime. The statute allows for a person who has been acquitted by the international tribunal to be retried if new evidence is found within five years, thus negating the well established legal concept of double jeopardy. The practicality of the court is also an issue. The attempt to coalesce the legal traditions of more than 150 countries into one ambiguously worded document is rife with problems. The text is vaguely worded leaving the newly established tribunal to interpret what the document means rather than being bound to a tightly written statute.

DOES NOT PREVENT GENOCIDE

11 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

1. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT DOES NOT DETER WAR CRIMES OR ATROCITIES- ONLY BRUTE FORCE CAN Jeremy Rabkin, Professor of Government at Cornell University, October 1998, Courting Disaster International Law: Yes International Criminal Court No, The America Spectator, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N With all their moral deficiencies, however, the Nuremberg trials had one powerful justification: at the time of the trials, the Allied Powers were the only government operating in Germany. These were international trials because there could not be any other kind at that moment. There was not another such trial until Madeleine Albright, as U.N. ambassador, pressed for an international tribunal to deal with war criminals in Yugoslavia. The idea was welcomed at that time as a way of registering Western repugnance at atrocities-- when the West was not willing to do much else apart from registering disapproval. What finally put a stop to ethnic cleansing and human slaughter in Bosnia (to the extent that they have been stopped) was the subsequent resort to air strikes and displays of military force. The threat of international trials of individual culprits (few of whom have been apprehended, and even fewer put on trial) was at best a minor factor. So it was after World War II. The Nuremberg trials did little to deter murderous regimes in the ensuing decades. Nazi crimes were brought to an end by bombers and tanks.

2. THE ICC DOES NOT DETER GENOCIDE- SUDAN HAS SIGNED THE TREATY AND STILL COMMITS ILLEGAL ATROCITIES Brett D. Schaefer, Fellow in International Regulatory Affairs at the Heritage Foundation, January 9, 2001, Overturning Clinton's Midnight Action on the International Criminal Court, The Heritage Foundation accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/InternationalOrganizations/EM708.cfm Supporters argue that the ICC will deter genocide and other atrocities, but this flies in the face of reality. Many repressive governments have signed the Rome Statute but continue to commit atrocities against civilians. The Sudanese government, for example, is embroiled in a civil war against Christians and others from the nation's southern region, and Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe has encouraged his supporters to murder political opponents and seize their property. Clearly, such regimes do not fear an ICC. They are more likely to see it as a useful vehicle for spurious accusations against the United States and its allies.

3. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT CANNOT SOLVE GENOCIDE- EMPIRICALLY PROVEN BY MILOSEVIC John R. Bolton, Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, January 18, 2000, Flaws Undermine Concept: Would Court Would be Ineffective, Threaten U.S. Powers, The American Enterprise Institute, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.aei.org/news/newsID.11201,filter./news_detail.asp First, the ICC wrongly assumes that war-crimes perpetrators will actually be deterred by the risk of possible conviction. But hard men like Hitler and Pol Pot are often not deterred from aggression, even by cold steel, let alone by a weak and distant institution with no real enforcement powers. Last year, Slobodan Milosevic, aided by the now- deceased Arkan, ignored the existing Yugoslav tribunal and inflicted grievous wrongs in Kosovo. Holding out the prospect of ICC deterrence to the truly weak and vulnerable is a cruel joke.

4. THE ICC DOES NOT DETER GENOCIDE OR CONFLICT- IN FACT, IT SCARES WARRING FACTIONS AWAY FROM THE PEACE TABLE TO CONTINUE THEIR HORRIFIC ACTS Gary Dempsey, Foreign Policy Analyst at the Cato Institute, August 19, 1998, Courting Disaster, The Cato Institute, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.cato.org/dailys/8-19-98.html The court also could jeopardize future U.S. efforts to resolve international conflicts. For example, if the court indicts the leaders of a warring faction while the United States is trying to conduct peace talks, that faction may respond by rejecting the resulting peace plan or staying away from the negotiating table altogether. That result would lead to more death and destruction, not less. In fact, according to former British envoy David Owen, a similar scenario unfolded in Bosnia in 1993 when the Serb faction rejected the Vance-Owen peace plan out of "fear that skeletons in their cupboard, such as massacres and war crimes, would be uncovered by the United Nations if they accepted the peace plan." The result: the Bosnian war dragged on for another 18 months.

12 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

US TARGETED FOR POLITICALLY MOTIVATED PROSECUTIONS

1. THE UNITED STATES IS DETERMINED TO PREVENT CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY, BUT IT MUST PROTECT ITSELF FROM POLITICALLY MOTIVATED PROSECUTIONS THROUGH THE ICC. Brett D. Schaefer, Fellow in International Affairs at the Heritage Foundation, June 21, 2004, Justice By Fiat, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Press/Commentary/ed062104e.cfm This is cold comfort. No nation is more dedicated than the United States to preventing crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide, and to bringing criminals to justice. The deplorable crimes committed in Abu Ghraib serve to support this contention. America continues to fully investigate and is proceeding to punish those responsible with the full weight of U.S. law. America's determination to punish perpetrators of these crimes offers no protection from politically motivated charges, however, as demonstrated by those alleging that the incident constituted war crimes and insinuating that the U.S. is covering up particulars of the incidents. These and similar experiences — like the ridiculous charges under Belgium's "Universal Competence" law against President George H. W. Bush, Secretary Powell, Vice President Cheney, and General Tommy Franks, among others, for their roles in Operations Desert Storm and Iraqi Freedom — reinforce America's determination to protect itself from politically motivated criminal allegations.

2. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT INVITES PROSECUTIONS ONTO AMERICANS- THEY CAN TAKE JURISDICTION OVER CRIMES WITHOUT THE CONSENT OF THE HOST COUNTRY Jeremy Rabkin, Professor of Government at Cornell University, October 1998, Courting Disaster International Law: Yes International Criminal Court No, The America Spectator, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N Mr. Clinton says that "jurisdiction over U.S. personnel should come only with U.S. ratification of the Treaty" and has called on the Senate to delay ratification until the court is adequately reformed. But U.S. personnel would be subject to prosecution anyway, because the court now has jurisdiction where the victims of a "war crime" or "crime of aggression" come from a ratifying state (even if the alleged perpetrators do not). Moreover, the treaty establishes a special provision by which a country can ask the court to take jurisdiction over some crime against its nationals without that country actually committing itself to turn over its own nationals to the court. This is an invitation to special raids on Americans. Or perhaps on American allies, such as Israel, which pleaded in vain at the Rome conference against successful Arab initiatives that effectively classify the building of Jewish settlements on the West Bank as a "war crime."

3. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT IS INCONSISTENT WITH AMERICAN STANDARDS- IT IS EMPIRICALLY PROVEN THAT IT ALLOWS FOR POLITICALLY MOTIVATED PROSECUTION John R, Bolton, Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, November 3, 2003, American Justice and the International Criminal Court, The American Enterprise Institute, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.aei.org/news/newsID.19407,filter./news_detail.asp Subjecting U.S. persons to this treaty, with its unaccountable Prosecutor and its unchecked judicial power, is clearly inconsistent with American standards of constitutionalism. This is a macro-constitutional issue for us, not simply a narrow, technical point of law. Our concerns about politically motivated charges against U.S. persons are not just hypothetical. Recently in Belgium, allegations of war crimes were brought against the President, the Vice President, the Secretaries of State and Defense, and former President Bush under that country’s notorious and far-reaching universal competence statute. That problem was brought closer to home when senior Belgian officials themselves were charged under the statute, and the law was subsequently amended to limit its scope. Without sufficient protection against such frivolous charges, responsible officials may be deterred from carrying out a wide range of legitimate functions across the spectrum, from actions integral to our national defense to peacekeeping missions or interventions in humanitarian crises or civil wars, such as in Liberia. Simply launching criminal investigations has an enormous political impact.

13 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

ICC BAD: DOES NOT HAVE JURISDICTION

1. THE ICC OVERREACHES ITS JURISDICTION- IT CLAIMS TO BE ABLE TO BRING CHARGES AGAINST NON-PARTY STATES, FEWER THAN HALF THE WORLDS NATIONS HAVE SIGNED ON, AND THE US IS ESPECIALLY VULNERABLE BECAUSE IT HAS THOUSANDS OF TROOPS BASED IN FOREIGN NATIONS David Davenport, Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution, August 27, 2003, Commentary: New Threat to U.S. Sovereignty, United Press International, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N Rather than involving the U.N. Security Council in referring cases, as had been done historically, this group wanted an independent prosecutor who could bring cases more proactively. Whereas international law limits the effect of treaties to those nations that sign them, proponents of the court wanted it to have jurisdiction over citizens of non-party states. And they wanted to add a new, undefined crime of "aggression" to the list of crimes the prosecutor could charge. These were overreaches of jurisdiction beyond anything done before and they were out of step with the recommendations of the International Law Commission charged by the United Nations with structuring the court. Therefore, the United States rightly objected to them. The surprise was not that the United States refused to go along with this expansive agenda for the court, but that proponents of the court rushed it through to approval without the support of major world powers. Even today, fewer than half the nations of the world, representing considerably less than half its population, have ratified the treaty.

2. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT OUTSOURCES THE RESPONSIBILITIES OF AMERICAN COURTS, THUS FORCING US TO SHARE THAT JURISDICTION WITH THAT INTERNATIONAL BODY Jeremy Rabkin, Professor of Government at Cornell University, October 1998, Courting Disaster International Law: Yes International Criminal Court No, The America Spectator, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N Years ago, the U.S. Judicial Conference warned that any international tribunal must observe all the guarantees of U.S. due process. Yet no such tribunal would follow the exact procedures specified in the Bill of Rights. Trial by jury, for example, is unusual outside the English-speaking world. Even if the procedures of the international court did meet American standards, the most serious objection would remain. If we can offer up Americans to international tribunals for some matters (such as "war crimes"), why not for others (such as narcotics trafficking)? Could we transfer broad swaths of responsibility from our own courts to international bodies? Does it make no difference whether our law is enforced by judges appointed by our own president (and confirmed by our own Senate) or by international officials selected through international horse-trading who operate by some shifting international "consensus"?

3. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT ASSERTS IT’S JURISDICTION EVEN WHEN SIGNATORY STATES DO NOT WANT IT TO BE, AND DOES NOT NEED THE APPROVAL OF THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL Jeremy Rabkin, Professor of Government at Cornell University, October 1998, Courting Disaster International Law: Yes International Criminal Court No, The America Spectator, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N The State Department sought to get by these fundamental problems by tying the court to the Security Council--where the United States has an absolute veto under the terms of the U.N. Charter. If the court could only be invoked by the Security Council, then the United States could block any action against American citizens or any action that would create a ticklish problem for American diplomacy. But the Rome conference insisted on a court that would have its own independent prosecutorial arm, acting on its own initiative. The court's jurisdiction is limited to cases involving signatory states--but its jurisdiction may be invoked even when the signatory state does not want it to be, to protect nationals of a signatory state even when the perpetrators are not from a signatory state. Even when the criminal's home state initiates prosecution in its own courts, the international court may launch a subsequent prosecution if it deems the original trial (or sanction) inadequate. If the court were up and running and Sudan were a party, the court could prosecute U.S. officials responsible for the cruise missile attack on a pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum.

14 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

DESTROYS US SUPPORT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS

1. FORCING AN INTERNATIONAL COURT ON THE US WILL KILL PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS- INSTEAD OF AN INCREASE IN US TROOP DEPLOYMENTS IT WILL DECREASE THE NUMBER OF TROOPS COMMITTED Brett D. Schaefer, Fellow in International Affairs at the Heritage Foundation, June 21, 2004, Justice By Fiat, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Press/Commentary/ed062104e.cfm Worse than the effort to impose the ICC on an unwilling United States is the potential impact of this effort on international peace and security. If the U.S. is not successful in renewing the Security Council resolution protecting non-ICC parties participating in United Nations peacekeeping operations from the court, U.S. participation in those operations would be severely curtailed. Moreover, U.S. support for those missions could be severely eroded and set the U.S. on a more aggressive course vis-à-vis the ICC, particularly if Congress takes offense. America is committed, proven through its sacrifice of blood and treasure, to opposing despots and bolstering democratic systems of government based on the rule of law. If successful, those lobbing politically motivated charges designed to deter American policy may reap the unintended harvest of a world rendered less secure and less peaceful by an America disinclined to act.

2. RATIFYING THE ICC DESTABILIZES US PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS- IT ALLOWS FOR INCREASED VIOLENCE AGAINST AMERICAN TROOPS Gary Dempsey, Foreign Policy Analyst at the Cato Institute, August 19, 1998, Courting Disaster, The Cato Institute, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.cato.org/dailys/8-19-98.html Furthermore, the court could destabilize future U.S.-led peacekeeping operations and endanger American lives in the process. Suppose the court handed down a verdict that the leaders of one faction had to pay reparations or return conquered territory to the victims of another faction, U.S. peacekeeping troops on the ground could find themselves in the messy position of either enforcing or refusing to enforce the court's judgment. Either way, one faction will be upset and U.S. peacekeepers will be caught in the middle -- a prospect that adds one more reason to get out of the peacekeeping business altogether.

3. US TROOPS PARTICIPATING IN PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS WILL BE UNIQUELY TARGETED BY HOSTILE FORCES. Jack Spencer, Senior Policy Analyst for Defense and National Security in the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for International Studies at The Heritage Foundation, July 3, 2003, Why US Troops Should Not Be Sent To Liberia, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/Africa/wm308.cfm Americans peacekeepers will be targets of political violence. The United States is not neutral, as peacekeepers must be if they are to be effective. U.S. troops would – rightfully – be on the side of the rebel forces trying to oust Charles Taylor. In fact, the Bush Administration has more than once identified Taylor as the problem and called for Taylor to leave the nation. Even if the U.S. were neutral, it would not be perceived as such, and this creates huge problems—the greatest of which is violence against U.S. forces. Organized forces that feel they are not being treated fairly by the United States would identify America as

4. UNITED STATES FORCES ARE TRAINED TO BE WAR FIGHTERS NOT PEACEKEEPERS

Jack Spencer, Senior Policy Analyst for Defense and National Security in the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for International Studies at The Heritage Foundation, July 3, 2003, Why US Troops Should Not Be Sent To Liberia, The Heritage Foundation, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.heritage.org/Research/Africa/wm308.cfm The U.S. armed forces do not make good peacekeepers. America’s armed forces are equipped and trained to fight wars, not be international peacekeepers. And that is the way it should be. As demonstrated in the three most recent major conflicts—Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq—only the United States has the capability to move large forces globally and defeat adversaries in relatively short amounts of time with relatively low casualty rates on both sides. They are able to conduct such operations because that is how they are equipped and trained. However, just because the United States can fight and win wars does not mean that it is the best nation at peacekeeping.

15 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

ICC BAD: HAS MANY STRUCTURAL PROBLEMS

1. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT IS ENTERING CRISIS MODE- THEY FACE NUMEROUS STRUCTURAL PROBLEMS Hague Justice Portal, September 23, 2008, The ICC: A Crisis of Maturity, Radio Netherlands Worldwide, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.rnw.nl/internationaljustice/specials/commentary/080923-HJP- commentary Ten years after the signing of the Rome Statute and some six years after it entered into force, the International Criminal Court (ICC) finds itself in troubled waters. The case against Thomas Lubanga, the first accused to appear before the Court, is on the verge of collapse and could well end in a complete failure. In the other situations before the Court, for example Uganda and Sudan, the progress made to date has been minimal. We have reached the point where more and more analysts use the word ‘crisis' to describe the current situation at the ICC. In a commentary written for the Hague Justice Portal, the author -who wishes to remain anonymous for personal reasons- analyses the different elements of this crisis and attempts to understand both their origins and their wider significance. In trying to balance several controversial strategic choices made by the ICC prosecutor and other structural problems at the Court, the author proposes a comprehensive overview of what could be the first ‘crisis of maturity' of the International Criminal Court.

2. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT FACES NUMEROUS FLAWS THAT ARE UNDERMINING ITS JURISDICTION. John R. Bolton, Former Undersecretary of State for Arms Control, November 14, 2002, The United States State Department, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.state.gov/t/us/rm/15158.htm The Court’s flaws are basically two-fold, substantive, and structural. As to the former, the ICC’s authority is vague and excessively elastic, and the Court’s discretion ranges far beyond normal or acceptable judicial responsibilities, giving it broad and unacceptable powers of interpretation that are essentially political and legislative in nature. This is most emphatically not a Court of limited jurisdiction. Crimes can be added subsequently that go beyond those included in the Rome Statute. Parties to the Statute are subject to these subsequently-added crimes only if they affirmatively accept them, but the Statute purports automatically to bind non-parties, such as the United States, to any such new crimes. It is neither reasonable nor fair that these crimes would apply to a greater extent to states that have not agreed to the terms of the Rome Statute than to those that have.

3. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT FACES TOO MANY FLAWS TOO BE SUCCESSFUL John R. Bolton, Former Undersecretary of State for Arms Control, November 14, 2002, The United States State Department, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.state.gov/t/us/rm/15158.htm As troubling as the ICC’s substantive and jurisdictional problems are, the problems raised by the Statute’s main structures -- the Court and the Prosecutor -- are still worse. The ICC does not, and cannot, fit into a coherent, international structural "constitutional" design that delineates clearly how laws are made, adjudicated or enforced, subject to popular accountability and structured to protect liberty. There is no such design, nor should there be. Instead, the Court and the Prosecutor are simply "out there" in the international system. Requiring the United States to be bound by this treaty, with its unaccountable Prosecutor and its unchecked judicial power, is clearly inconsistent with American standards of constitutionalism. This is a macro-constitutional issue for us, not simply a narrow, technical point of law. We are considering, in the Prosecutor, a powerful and necessary element of executive power, the power of law-enforcement. Never before has the United States been asked to place any of that power outside the complete control of our national government without our consent. Our concern goes beyond the possibility that the Prosecutor will target for indictment the isolated U.S. soldier who violates our own laws and values by allegedly committing a war crime. Our principal concern is for our country’s top civilian and military leaders, those responsible for our defense and foreign policy. They are the ones potentially at risk at the hands of the ICC’s politically unaccountable Prosecutor, as part of an agenda to restrain American discretion, even when our actions are legitimated by the operation of our own constitutional system.

16 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

CANNOT DEFINE AGGRESSION

1. AN INTERNATIONAL COURT CANNOT DEFINE AGGRESSION, WHICH RENDERS ITS POINT USELESS. Alisha Telici, Corporate Counsel at Charles Schwab, Winter 2004, Note: The International Criminal Court: Is the United States overlooking an easier way to hold Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden accountable for their actions, The New England Law Review, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N Complementarity aside, the most controversial of the four crimes within the jurisdiction of the ICC is the crime of aggression. In contrast, the inclusion of other core crimes, such as the crime of genocide, passed through the Rome conference quietly. While most Member States agreed that agressionw as a crime that should be punishable by the ICC, the debate centered on how to set out the exact parameters of aggression in the Rome Statute. Thus, the Rome Conference was unable to produce a definition of crimes of aggression upon which the majority of the attending Member States could agree. Currently, the Statute does not contain a definition for the crime of aggression instead it provides: The Court shall exercise jurisdiction over the crime of aggression once a provision is adopted in accordance with articles 121 and 123 defining the crime and setting out the conditions under which the Court shall exercise jurisdiction with the respect to the crime. Such a provision shall be consistent with the relevant provision of the Charter of the United Nations. Articles 121 and 123 provide for amendments to the Rome Statute and the statutory review process respectively.

2. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT WEAKENS THE UN SECURITY COUNCIL BY TAKING AWAY ITS POWER TO DETERMINE WHAT IS AN ACT OF AGGRESSION Marc Grossman, Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, May 6, 2002, American Foreign Policy and the International Criminal Court, Congressional Information Services, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N Second, the treaty approved in Rome dilutes the authority of the UN Security Council and departs from the system that the framers of the UN Charter envisioned. The treaty creates an as-yet-to-be defined crime of "aggression," and again empowers the court to decide on this matter and lets the prosecutor investigate and prosecute this undefined crime. This was done despite the fact that the UN Charter empowers only the Security Council to decide when a state has committed an act of aggression. Yet the ICC, free of any oversight from the Security Council, could make this judgment.

3. THE ROME STATUE AND THE AMENDMENTS TO THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT CREATE TWO DIFFERENT DEFINITIONS FOR WHAT CONSTITUTES AGGRESSION Anja Seibert-Fohr, head of the Minerva Research Group at the Max-Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law in Heidelberg, Germany, November 18, 2008, The Crime of Aggression: Adding a Definition to the Rome Statue of the ICC, The American Society of International Law, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.asil.org/insights081118.cfm#author What does this now mean for the future structure of the Rome Statute, if the State parties adopt the definition of aggression? Since the amendment only enters into force with respect to those States Parties ratifying or depositing an instrument of acceptance, there may end up being two different sets of application: The Rome Statute in its current design would apply to those States Parties that do not ratify or formally accept the amendment. The amended Statute will only apply to those having accepted the amendment one year after the deposit of their instruments of ratification or acceptance. In order to ensure a uniform text that reflects the differences in application, the adoption of an Additional Protocol to the Rome Statute on the Crime of Aggression could be considered. This method of amendment is common, for example, in the area of human rights and international humanitarian law. The procedure outlined in Article 121(5) could be realized adequately by adopting such an additional protocol. Since the amendment necessitates adjustments with respect to the ratione personae jurisdiction it could be sensible to combine all relevant provisions on the crime of aggression together in one document.

17 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTIONS BAD: TOO SLOW TO RESPOND

1. MULTILATERALISM LEADS TO INACTION- GENOCIDE AND PROLIFERATION RESULTS. Brent Jentleson, Professor of Public Policy and Political Science at Duke University, Winter 2004, Tough Love Multilateralism, The Washington Quarterly, accessed 12/10/2008, http://mitpress.mit.edu/journals/pdf/wash_27_1_7_0.pdf For multilateralists, this shift away from force only as a last resort requires breaking out of the tendency to conflate conflict avoidance with security enhancement, making the former instead of the latter the criteria for success. In diplomacy, the desire to come to agreement and avoid conflict comes with the territory. It should, but as a preference, not a postulate. Certain situations and adversaries necessitate the willingness to threaten or use force. The international community will never be taken seriously if its position comes across as “Please, don’t make me do this.” If adversaries or aggressors know that force will be used only as a last resort, only after the incremental pursuit of an array of options, they retain the strategic initiative and tactical advantage. This sequential last-resort approach forfeits any prospect of acting preventively. It would consign the world to wait until episodes of ethnic cleansing and genocide have run their horrific courses, terrorist networks have become deeply entrenched, or weapons of mass destruction (WMD) have been further proliferated or even been used.

2. UTILIZING MULTILATERALISM GUARANTEES FAILURE- NATIONS WHO LACK THE RESOURCES TO SOLVE THE PROBLEM CANNOT DEMAND THAT THEY BE SOLVED. US UNILATERALISM MUST PRECEDE MULTILATERALISM FOR ACTION TO BE EFFECTIVE- EMPIRICALLY PROVEN BY BOSNIA Robert Kagan, Senior Associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Summer 1998, The Benevolent Empire, Foreign Policy, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N This insufficiency is the fatal flaw of multilateralism, as the Clinton administration learned in the case of Bosnia. In world that is not genuinely multipolar—where there is instead a widely recognized hierarchy of power—multilateralism, if rigorously pursued, guarantees failure in meeting international crises. Those nations that lack the power to solve an international problem cannot be expected to take the lead in demanding the problem be solved. They may even eschew the exercise of power altogether, both because they do not have it and because the effective exercise of it by someone else, such as the United States, only services to widen the gap between the hegemon and the rest. The lesson President Bill Clinton was supposed to have learned in the case of Bosnia is that to be effective, multilateralism must be preceded by unilateralism. In the toughest situations, the most effective multilateral response comes when the strongest power decides to act, with or without others, and then asks its partners whether they will join. Giving equal say over international decisions to nations with vastly unequal power often means that the full measure of power that can be deployed in defense of the international community’s interests will, in fact, not be deployed.

3. MULTILATERALISM FAILS- THE UNITED NATIONS FAILURE TO SOLVE THE CRISES IN KOSOVO, RWANDA, AND IRAQ PROVES THAT UNITED STATES UNILATERALISM IS ESSENTIAL TO WORLD STABILITY. WE ARE THE ONLY COUNTRY WILLING TO SPEND THE MONEY IT TAKES TO SOLVE WORLD PROBLEMS. Gary Schmidt, Executive Director at the Project for the New American Century, March 30, 2003, The Pittsburgh Post Gazette, accessed 12/10/2008, online L/N For example, for all the huffing and puffing about the need to have this war sanctioned by the United Nations, it goes without saying that neither France nor China is especially eager to constrain its national security decisions because of U.N. mandates. Indeed, in the continuing case of North Korea’s violation of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, France and China have actively sought to push the matter way from U.N. consideration. The fact is, the United Nations can only operate by majority consensus, and this means that its decisions will be governed by the particular interests of the individual member states of the Security Council—not some disembodied, benign voice of the “international community”. As the failure to back up its own resolution on Iraq and to act decisively in the cases of Rwanda and Kosovo in the 1990s shows, the United Nations cannot be trusted to be the sole arbiter of these matters. No. The unavoidable reality is that the exercise of American power is key to maintaining what peace and order there is in the world today.

18 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

INTERNATIONAL TRIBUNALS EMPIRICALLY FAIL

1. THE KHMER ROGUE TRIBUNALS PROVE INTERNATIONAL COURTS FAIL- THEY HAVE RECENTLY STALLED BECAUSE THE DEFENSE ATTORNEY HAS CALLED FOR A NEW TRANSLATION OF THE LAW Claire Duffett, Special to Law.com, December 10, 2008, Khmer Rouge Genocide Tribunal Stumbles as French Defense Laywer Demands New Translation, Law.com International News, accessed 12/10/2008, http://www.law.com/jsp/law/international/LawArticleIntl.jsp?id=1202426601165 The proceedings of Cambodia's United Nations-backed genocide tribunal briefly descended into chaos last week, as defense lawyers for Khieu Samphan, former Cambodian head-of-state under the Khmer Rouge, argued the case must halt until all documents are translated into French. A tumultuous press conference on Dec. 4, marked by the trademark antics of Samphan's French defense attorney, Jacques Vergès, preceded a more productive hearing on Dec. 5 that paved the way for the first of five regime leaders detained by the tribunal to go to trial. Accusations of corruption, disagreement among prosecutors and overspending have all helped delay the trials. According to a timeline created in 2006, all five trials should already be completed. Now, they are expected to continue through 2010.At the press conference, Khmer Rouge victims bemoaned the slow and disjointed progress of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, the tribunal's official name. "We don't want a trial by media," complained Australian prosecutor William Smith, from underneath a canopy of sound booms. Chaos, however, is exactly what Jacques Vergès appears to want.

2. INTERNATIONAL TRIBUNALS FORMED AFTER RWANDA AND YUGOSLAVIA FAILED TO PROSECUTE PERPETRATORS OF GENOCIDE. Laura Catlett, Writer for the Virginia Law Journal, November 7, 2007, International Tribunals Fail to Deter War Crimes, Drumbl’s Book Charges The international tribunals formed in response to crimes in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia have failed to effectively deter war crimes and punish perpetrators, said Washington and Lee law professor Mark Drumbl during a talk at the Law School Nov. 1. Drumbl recently penned a book on the subject, “Atrocity, Punishment, and International Law,” which aims to reveal the weaknesses in the current international criminal tribunals and offer more effective strategies to prosecute those who commit mass atrocities such as genocide. “War crimes target everyone,” Drumbl said. “We are all victims.…We need to set up a system in these states where oppressors bear personal burdens for crimes.” After the Rwandan genocide and the conflict in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the United Nations established two international criminal tribunals to prosecute those who participated in genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes in each of the conflicts. Drumbl explained that the tribunals had two goals: to hold individuals accountable for participating in mass atrocities, and to deter others from committing similar crimes in the future by demonstrating that they would be prosecuted. Both tribunals are still prosecuting individuals for the crimes.

3. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL IN RWANDA LET THE MASTERMINDS OF THE GENOCIDE SERVE THEIR SENTENCES IN COUNTRY CLUB-LIKE CONDITIONS Tom Farer, International Lawyer and Human Rights Activist, 2000, Restraining the Barbarians: Can International Criminal Law Help, The Human Rights Quarteraly, Vol. 22 Num. 1, acessed 12/10/2008, online L/N A second question an agnostic might pose is whether a system shaped by the human rights sensibility in its most distilled form will tolerate effective procedures and intimidating punishments Despite pleas from the post-holocaust government in Rwanda—in effect, therefore, from the survivors—the United Nations denied its own creation, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwandan (ICTR), the authority to impose capital punishment. Even life terms, with or without the prospect of parole, are deemed “inhuman” by some European civil libertarians. Moreover, those convicted by the ICTR will serve their sentence in a state designated by the ICTR from a list of states that eave expressed a willingness to take the convicted, provided that the prisons meet internationally recognized prison conditions. At present, hover, there is no prison in Rwanda that even approaches internationally recognized minimum prison conditions, raising the possibility that those convicted fo masterminding the genocide will serve their sentences in country club settings, while those convicted by Rwandan courts will ser their time in appalling prison conditions.

19 West Coast Publishing 2009 January-February LD- International Criminal Court

ICC BAD: NO CHECKS AND BALANCES