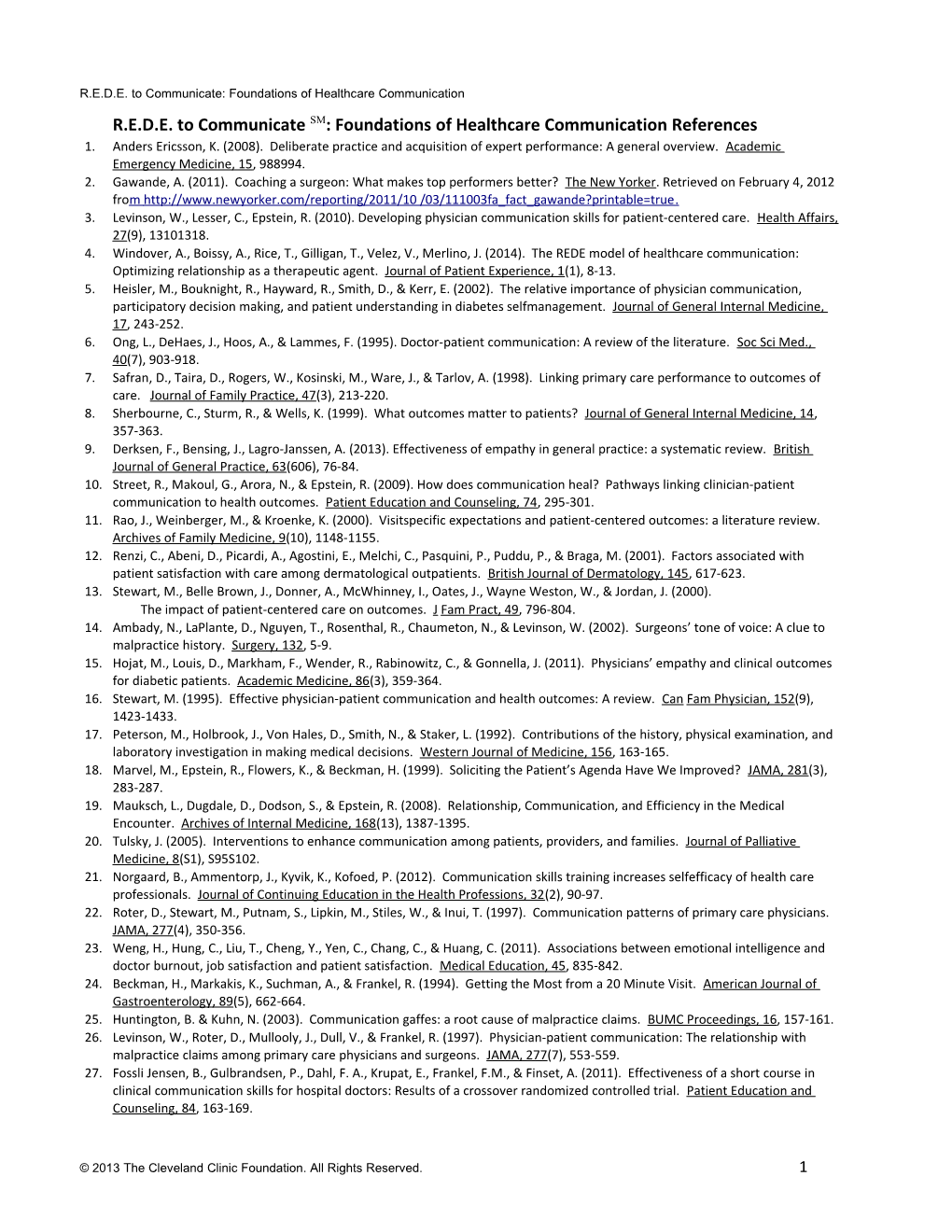

R.E.D.E. to Communicate: Foundations of Healthcare Communication R.E.D.E. to Communicate SM: Foundations of Healthcare Communication References 1. Anders Ericsson, K. (2008). Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: A general overview. Academic Emergency Medicine, 15, 988994. 2. Gawande, A. (2011). Coaching a surgeon: What makes top performers better? The New Yorker. Retrieved on February 4, 2012 fro m http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/10 /03/111003fa_fact_gawande?printable=true . 3. Levinson, W., Lesser, C., Epstein, R. (2010). Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Affairs, 27(9), 13101318. 4. Windover, A., Boissy, A., Rice, T., Gilligan, T., Velez, V., Merlino, J. (2014). The REDE model of healthcare communication: Optimizing relationship as a therapeutic agent. Journal of Patient Experience, 1(1), 8-13. 5. Heisler, M., Bouknight, R., Hayward, R., Smith, D., & Kerr, E. (2002). The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes selfmanagement. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 17, 243-252. 6. Ong, L., DeHaes, J., Hoos, A., & Lammes, F. (1995). Doctor-patient communication: A review of the literature. Soc Sci Med., 40(7), 903-918. 7. Safran, D., Taira, D., Rogers, W., Kosinski, M., Ware, J., & Tarlov, A. (1998). Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. Journal of Family Practice, 47(3), 213-220. 8. Sherbourne, C., Sturm, R., & Wells, K. (1999). What outcomes matter to patients? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14, 357-363. 9. Derksen, F., Bensing, J., Lagro-Janssen, A. (2013). Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. British Journal of General Practice, 63(606), 76-84. 10. Street, R., Makoul, G., Arora, N., & Epstein, R. (2009). How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling, 74, 295-301. 11. Rao, J., Weinberger, M., & Kroenke, K. (2000). Visitspecific expectations and patient-centered outcomes: a literature review. Archives of Family Medicine, 9(10), 1148-1155. 12. Renzi, C., Abeni, D., Picardi, A., Agostini, E., Melchi, C., Pasquini, P., Puddu, P., & Braga, M. (2001). Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. British Journal of Dermatology, 145, 617-623. 13. Stewart, M., Belle Brown, J., Donner, A., McWhinney, I., Oates, J., Wayne Weston, W., & Jordan, J. (2000). The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract, 49, 796-804. 14. Ambady, N., LaPlante, D., Nguyen, T., Rosenthal, R., Chaumeton, N., & Levinson, W. (2002). Surgeons’ tone of voice: A clue to malpractice history. Surgery, 132, 5-9. 15. Hojat, M., Louis, D., Markham, F., Wender, R., Rabinowitz, C., & Gonnella, J. (2011). Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Academic Medicine, 86(3), 359-364. 16. Stewart, M. (1995). Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: A review. Can Fam Physician, 152(9), 1423-1433. 17. Peterson, M., Holbrook, J., Von Hales, D., Smith, N., & Staker, L. (1992). Contributions of the history, physical examination, and laboratory investigation in making medical decisions. Western Journal of Medicine, 156, 163-165. 18. Marvel, M., Epstein, R., Flowers, K., & Beckman, H. (1999). Soliciting the Patient’s Agenda Have We Improved? JAMA, 281(3), 283-287. 19. Mauksch, L., Dugdale, D., Dodson, S., & Epstein, R. (2008). Relationship, Communication, and Efficiency in the Medical Encounter. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168(13), 1387-1395. 20. Tulsky, J. (2005). Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 8(S1), S95S102. 21. Norgaard, B., Ammentorp, J., Kyvik, K., Kofoed, P. (2012). Communication skills training increases selfefficacy of health care professionals. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 32(2), 90-97. 22. Roter, D., Stewart, M., Putnam, S., Lipkin, M., Stiles, W., & Inui, T. (1997). Communication patterns of primary care physicians. JAMA, 277(4), 350-356. 23. Weng, H., Hung, C., Liu, T., Cheng, Y., Yen, C., Chang, C., & Huang, C. (2011). Associations between emotional intelligence and doctor burnout, job satisfaction and patient satisfaction. Medical Education, 45, 835-842. 24. Beckman, H., Markakis, K., Suchman, A., & Frankel, R. (1994). Getting the Most from a 20 Minute Visit. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 89(5), 662-664. 25. Huntington, B. & Kuhn, N. (2003). Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. BUMC Proceedings, 16, 157-161. 26. Levinson, W., Roter, D., Mullooly, J., Dull, V., & Frankel, R. (1997). Physician-patient communication: The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA, 277(7), 553-559. 27. Fossli Jensen, B., Gulbrandsen, P., Dahl, F. A., Krupat, E., Frankel, F.M., & Finset, A. (2011). Effectiveness of a short course in clinical communication skills for hospital doctors: Results of a crossover randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 84, 163-169.

© 2013 The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. All Rights Reserved. 1 R.E.D.E. to Communicate: Foundations of Healthcare Communication

28. Bar, M., Neta, M., & Linz, H. (2006). Very first impressions. Emotion, 6 (2), 269-278. 29. Chaplin, W., Phillips, J., Brown, J., Clanton, N., & Stein, J. (2000). Handshaking, gender, personality, and first impressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(1), 110-117. 30. Platt, F., Gaspar, D., Coulehan, J., Fox, L., Adler, A., Weston, W., Smith, R., & Stewart, M. (2001). “Tell me about yourself”: The patient-centered interview. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134(11), 1079-1085. 31. Beckman, H. & Frankel, R. (1984). The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data. Annals of Internal Medicine, 101, 692-696. 32. Barrier, P., Li, J., & Jensen, N. (2003). Two words to improve physician-patient communication: what else? Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 78, 211-214. 33. Heritage, J., Robinson, J., Elliott, M., Beckett, M. & Wilkes, M. (2007). Reducing patients’ unmet concerns in primary care: the difference one word can make. J Gen Intern Med, 22(10), 1429-1433. 34. Middleton, J., McKinley, R., Gillies, C. (2006). Effect of patient completed agenda forms and doctors education about the agenda on the outcome of consultations: randomized controlled trial. BMJ, doi:10.1136/bmj.38841.444861.7C. 35. Barsky, A. (1981). Hidden reasons some patients visit doctors. Diagnosis and Treatment, 94 (4/1), 492-498. 36. Burack, R. & Carpenter, R. (1983). The predictive value of the presenting complaint. Journal of Family Practice, 16(4), 749-754. 37. Tallman, K., Janisse, T., Frankel, R., Hee Sung, S., Krupat, E., & Hsu, J. (2007). Communication practices of physicians with high patient-satisfaction ratings. The Permanente Journal, 11(1), 19-29. 38. Darley, J. & Batson, D. (1973). “From Jerusalem to Jericho”: A study of situational and dispositional variables in helping behavior, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17(1), 100-108. 39. Hojat, M. Vergare, M., Maxwell, K., Brainard, G., Herrine, S., Isenberg, G., Veloski, J., & Gonnella, J. (2009). The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Academic Medicine, 84(9), 1182-1191. 40. Levinson, W., Corawara-Bhat, R., & Lamb, J. (2000). A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA, 284(8), 1021-1027. 41. Spiro, H.M., McCrea Curnen, M.G., Peschel, E. & St. James, D. (1993). Empathy and the Practice of Medicine: Beyond Pills and the Scalpel. Binghamton, New York: Vail-Ballou Press. 42. Coulehan, J., Platt, F., Egener, B., Frankel, R., Lin, C., Lown, B., Salazar, W. (2001). “Let me see if I have this right…”: Words that help build empathy. Annals of Internal Medicine, 135, 221-227. 43. Rautalinko, R., Lisper, H., & Ekehammar, B. (2007). Reflective listening in counseling: Effects of training time and evaluator social skills. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 61(2), 191-209. 44. Langewitz, W., Denz, M., Keller, A., Kiss, A., Ruttimann, S., & Wossmer, B. (2002). Spontaneous talking time at start of consultation in outpatient clinic: Cohort study. BMJ, 325, 682-683. 45. Weston, W., Brown, J., Stewart, M. (1989). Patientcentred interviewing part I: Understanding patients’ experiences. Can Fam Physician, 35, 147-151. 46. Helman, C. (1981). Disease versus illness in general practice. Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 548-552. 47. Carrillo, J., Green, A., & Betancourt, J. (1999). Crosscultural primary care: A patient-based approach. Annals of Internal Medicine, 130, 829-834. 48. Kleinman, A., Eisenberg, L., & Good, B. (1978). Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Annals of Internal Medicine, 88(2), 251-258. 49. Schenker, Y., Fernandez, A., Sudore, R., & Schillinger, D. (2011). Interventions to improve patient comprehension in informed consent for medical procedures: A systematic review. Medical Decision Making, 31, 151-173. 50. Schillinger, D., Piette, J., Grumbach, K., Wang, F., Wilson, C., DAher, C., Leong-Grotz, K.,Castro, C., Bindman, A. (2003). Closing the loop: Physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163, 83-90. 51. Kessels, R. (2003). Patients’ memory for medical information. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 96, 219-222. 52. National Center for Education Statistics (2006). The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. U.S. Department of Education. Accessed April 25, 2013 at : http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf . 53. Misra-Hebert, A. & Issacson, J. (2012). Overcoming health disparities via better cross-cultural communication and health literacy. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, 79(2), 127-133.

© 2013 The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. All Rights Reserved. 2 R.E.D.E. to Communicate: Foundations of Healthcare Communication R.E.D.E. to CommunicateSM: Foundations of Healthcare Communication Skills Checklist Relationship:

Establishment Development Engagement Phase I Phase II Phase III

Convey value & respect with the welcome Engage in reflective listening Share diagnosis & information • Review chart in advance & comment on their • Nonverbally – e.g., direct eye contact, • Orient patient to the education & planning history forward lean, nodding portion of the visit • Knock & inquire before entering room • Verbally using continuers such as • Present a clear, concise diagnosis “mm-hmm”, “I see”, “go on” or • Greet patient formally with smile & handshake reflecting the underlying meaning or • Pause if necessary • Introduce self & team ; clarify role(s) emotion of what is said “What I hear • Provide additional education, if desired & • Position self at patient’s eye level you saying is…” or helpful to the patient “Sounds like…” • Frame information in the context of the • Recognize & respond to signs of physical or • Avoid expressing judgment, getting patient’s perspective emotional distress distracted, or redirecting speaker • Attend to patient’s privacy • Express appreciation for sharing

• Make a brief patient-focused social comment, if appropriate

Collaboratively set the agenda Elicit patient narrative Collaboratively develop treatment plan • Orient patient to elicit a list of presenting • Use transition statement to orient • Describe treatment goals & options concerns patient to the history of present illness including risks, benefits, & alternatives • Use an open-ended question to initiate survey • Use open-ended question(s) to initiate • Elicit patient’s preferences & integrate into • Ask patient to list all concerns for the visit or patient narrative a mutually agreeable plan hospital stay (e.g., “What else?”) • Maintain the narrative with verbal • Check for mutual understanding • Summarize list of concerns to check accuracy; ask patient to prioritize & nonverbal continuers • Confirm patient’s commitment to plan • Propose agenda that incorporates patient & “Tell me more…” or “What next?” • Identify potential treatment barriers & clinician priorities; obtain patient agreement • Summarize patient narrative to check need for additional resources accuracy • Fill in gaps with close-ended questions

Introduce the computer, if applicable Provide closure • Orient patient to computer • Alert patient that the visit is ending

• Explain benefit to the patient • Affirm patient’s contributions & collaboration during visit • Include patient whenever possible (e.g., share • Arrange follow-up with patient AND lab work or scans) consultation with other team members • Maintain eye contact when possible • Provide handshake & a personal goodbye • Stop typing & attend to patient when emotion arises

© 2013 The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. All Rights Reserved. 3 R.E.D.E. to Communicate: Foundations of Healthcare Communication

Demonstrate empathy using SAVE Explore the patient’s perspective Dialogue throughout using ARIA • Recognize emotional cues & respond “in the using VIEW • Assess using open-ended questions moment” • Vital activities (occupational, o What the patient knows about • Allow space to be with the patient & the interpersonal, intrapersonal) “How diagnosis & treatment emotion without judgment does it disrupt your daily activity?” or • Clarify the emotion if needed “How does it impact your o How much & what type of education functioning?” • Recognize emotion evoked in you & refrain the patient desires/needs • Ideas from trying to fix or reassure o • Demonstrate verbally with SAVE o “Often people have a sense of what Patient treatment preferences o Support/partnership: “I’m here for you. is happening. What do you think is Health literacy Let’s work together…” o wrong?” or “Do you know others who have had similar symptoms?” Acknowledge:“This has been hard on you.” • Reflect patient meaning and emotion • Expectations o Validate: “Most people would feel the • Inform way you do.” “What are you hoping I (we if part o Tailor information to patient o Speak slow of a team) can do for you today?” & provide only a few small chunks of o Emotion naming: “You seem sad.” • Worries (concerns, fears) information at a time • Demonstrate nonverbally – doing only that “What worries you most about it?” which feels natural & authentic to you o Use understandable language & visual aids

• Assess patient understanding & reaction to the information provided

© 2013 The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. All Rights Reserved. 4