HS502, sections 1 (Mondays) and 2 (Tuesdays): Syllabus Dr. Chris Armstrong Spring 2010 Bethel Seminary Mar 29 – Jun 4 Office: A212; 651-635-8793 Mondays/Tuesdays, 1 pm – 5 pm email: [email protected]

CHURCH IN THE MODERN WORLD

COURSE DESCRIPTION: An introduction to the major movements in Christian history from the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century to the present.

COURSE OBJECTIVES: 1. Recount and explain the significant events in the church's history since 1500. 2. Evaluate the church's relationship to its surrounding social and intellectual environment. 3. Critically evaluate both primary and secondary evidence used in historical understanding. 4. Relate the ecclesiastical and doctrinal traditions of the past to contemporary movements and theological thinking.

REQUIRED TEXTS: González, Justo. Reformation to the Present Day, vol. 2 of The Story of Christianity. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985. ISBN 0060633166 Bettenson, Henry, and Chris Maunder, eds. Documents of the Christian Church, third edition. London: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0192880713

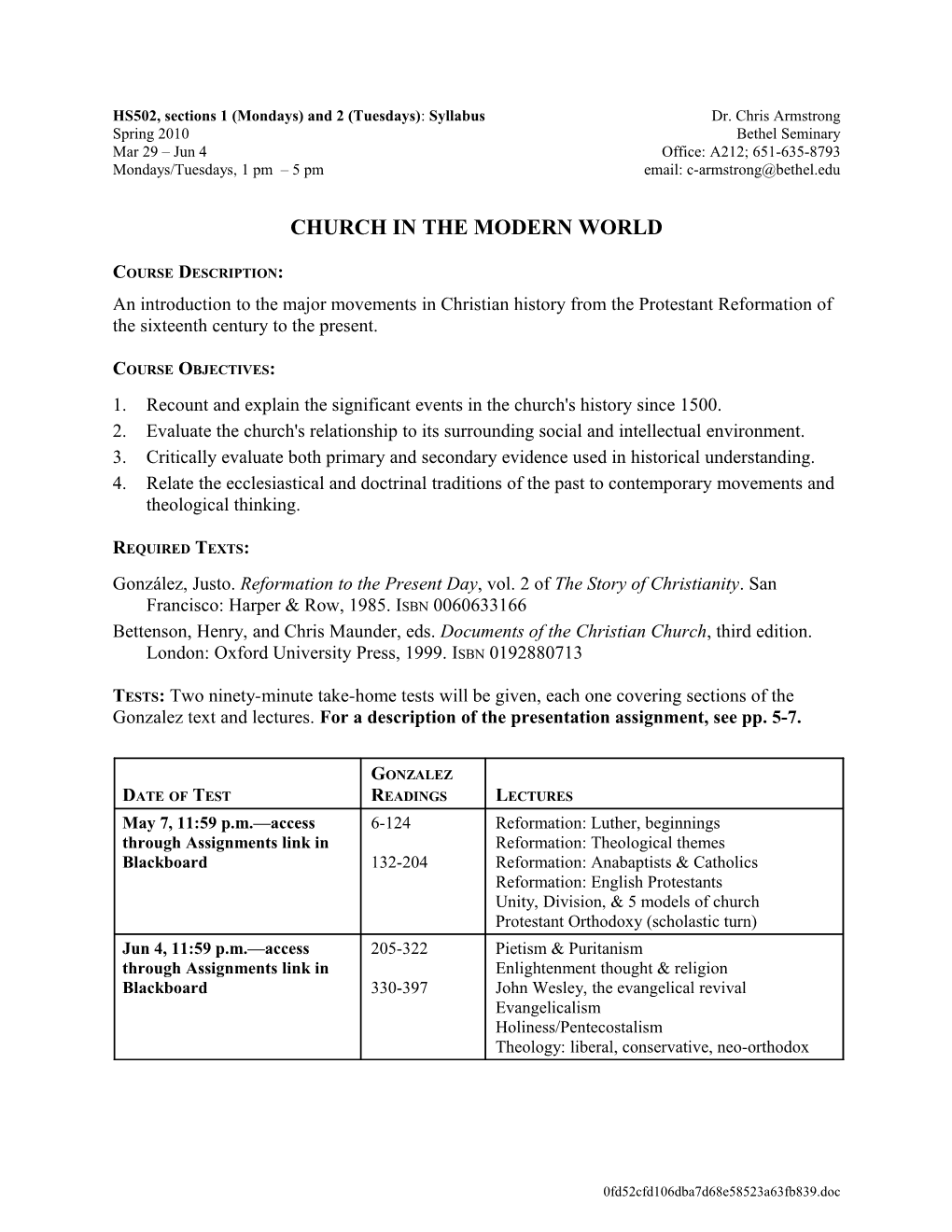

TESTS: Two ninety-minute take-home tests will be given, each one covering sections of the Gonzalez text and lectures. For a description of the presentation assignment, see pp. 5-7.

GONZALEZ DATE OF TEST READINGS LECTURES May 7, 11:59 p.m.—access 6-124 Reformation: Luther, beginnings through Assignments link in Reformation: Theological themes Blackboard 132-204 Reformation: Anabaptists & Catholics Reformation: English Protestants Unity, Division, & 5 models of church Protestant Orthodoxy (scholastic turn) Jun 4, 11:59 p.m.—access 205-322 Pietism & Puritanism through Assignments link in Enlightenment thought & religion Blackboard 330-397 John Wesley, the evangelical revival Evangelicalism Holiness/Pentecostalism Theology: liberal, conservative, neo-orthodox

0fd52cfd106dba7d68e58523a63fb839.doc HS502: Syllabus Page 2

Gonzalez Study Items:

Test I

Erasmus The Beggars Luther: reform Catherine de Medici Luther: theology Ignatius Loyola Charles V James I Zwingli Cornelius Jansen First Anabaptists Arminius Calvin: Institutes Descartes Calvin: Geneva Hume Henry VIII Kant John Knox George Fox

Test II

Spener and Francke Bonhoeffer Zinzendorf Schleiermacher John Wesley Hegel Roger Williams Kierkegaard Whitefield/Edwards Pius IX Second Awakening Leo XIII Slavery and Civil War William Carey Joseph Smith the Russian Church criollos John XXIII and Vatican II French Revolution Barth

NOTE: The questions on the Gonzalez text will all be matching. Each set of twenty items will be divided into four five-item units, with six options listed for each set of five.

Two notes on paper-writing:

First, a friend of mine at Westmont has done students everywhere a service with a very strict (and appropriate) list of suggestions about how to put essays together for his classes. You can find my friend’s “A Few (Strong) Suggestions on Essay Writing” at the following web address: http://www.westmont.edu/~work/material/writing.html. Please don’t let his suggestions paralyze you, as I am not as strict as he is. However, following his suggestions will result in a near- guaranteed improvement in your papers for this course—and future courses.

Second, some students will benefit from my favorite web source for writing help; all should find something useful here. It is a “master list” of helps for writers that I put together while working as a writing tutor at Duke. You can find this list at the following web address: http://uwp.aas.duke.edu/wstudio/resources/writing.html. Each subject link provides a set of helps in that subject area. Especially helpful are the materials under “Drafting,” “Revising,” and “Editing for Usage and Grammar.” See also the “grammar and reference” link on the left.

0fd52cfd106dba7d68e58523a63fb839.doc HS502: Syllabus Page 3

Grading: Presentation—25% Two Tests—15% each = 30% total Final Paper—35% Discussion questions—10%

Academic Course Policies:

Please familiarize yourself with the catalog requirements as specified in Academic Course Policies document found on the Syllabus page in Blackboard. You are responsible for this information, and any academic violations, such as plagiarism, will not be tolerated. Plagiarism will result in an “F” on the course.

COURSE SCHEDULE

DATE COURSE TOPICS* ASSIGNMENTS

LECTURES: Reformation: Luther, Read two web articles—see below 3/29-30 beginnings, theological themes

PRESENTATIONS: Anabaptists, Have Bettenson 202-33, 236-38 Catholic Reformation read before class session 4/5-6 LECTURES: Reformation: (Bettenson readings for) Anabaptists & Catholics; Unity, Presentations A, B Division, & 5 Models of Church

Reformation: English Protestants Have articles on Thomas More (in BB) read. View in class and 4/12-13 discuss: A Man for All Seasons

VIDEO: A Man for All Seasons

PRESENTATIONS: Puritanism, (Bettenson readings for) Quakers Presentations C, D 4/19-20 LECTURES: Protestant Orthodoxy In-class: Pietism primary readings (scholastic turn), Pietism & Puritanism and discussion

Blackboard readings on E, F, G Reading and Research Week 1 (no postings or presentations) 4/26-27 Proposal and outline for final research paper: (submit under Assignments by 11:59 pm, 4/30)

Blackboard readings on E, F, G Reading and Research Week 2 (no postings or presentations) 5/3-4 Test I due in Assignments area of Blackboard (11:59 pm, 5/7)

0fd52cfd106dba7d68e58523a63fb839.doc HS502: Syllabus Page 4

PRESENTATIONS: Oxford (Bettenson readings for) movement, Liberalism Presentations H, I 5/10-11 LECTURES: Enlightenment Thought & Religion, John Wesley, Evangelical Revival

PRESENTATIONS: Vatican II, New (Bettenson readings for) voices Presentation J, K 5/17-18 LECTURES: Theology: Liberal, Fundamentalist

LECTURES: Theology: Neo- No presentations 5/24-25 Orthodox; Holiness/Pentecostalism

NO PRESENTATIONS Test II due in Blackboard (11:59 pm, 6/4) 5/31 – 6/1 LECTURE TUESDAY (NO CLASS Final research paper due in MONDAY): Modernity, 20th-c. Blackboard (11:59 pm, 6/4) Literary Revival

* NOTE: Lecture topics may vary from this chart. This is a general guide only. For Week 2: Please read the following: http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/robinson- sources.html and http://academic.bowdoin.edu/WritingGuides/ -- choose "How to read a primary source" from left navigation bar. Syllabus continued on next page

0fd52cfd106dba7d68e58523a63fb839.doc HS502: Syllabus Page 5

Presentations: The assignment

Each student, ideally with one or two other students, will present on one of the topics described in the grid titled “Presentation topics and primary readings” on p. 7 in this syllabus, using the primary and secondary sources provided for this purpose. This assignment is worth more than any other part of your work for this course (30% of the final grade). Prepare accordingly!

Your primary readings will come from three sources—all indicated in the grid on p. 7: (1) Bettenson, (2) documents scanned and posted in the “course documents” area of our course’s Blackboard site, and (3) web sources linked from the grid (you can click on these directly from the electronic copy of this syllabus, here or posted in the “syllabus” area of this class’s Blackboard site).

These primary readings tend to focus on the theological thought of historical figures and movements. In your presentations, your job is to situate the primary readings in history and to suggest applications of that thought for a modern lay Christian audience. Think of yourself as giving your presentation to an adult Sunday school class at your church.

In preparing your presentation, you will use secondary sources—see the Presentations and Papers: Secondary Sources link under Course Documents on Blackboard for some sources to start with, all of which are in the seminary library, and many of which are on the reserve shelf for this course—to contextualize that thought in history.

Each presenter should aim to take about 10 minutes in formal presentation. Discussion will follow after both/all of the presenters have finished, and should take up about 10-20 more minutes. NOTE: Presenters who go over 10 minutes risk losing marks. This is because (1) conciseness is one of the most important and difficult skills in historical work, and (2) discussion is an important part of what we will be doing together.

Your classmates will be far from passive in these presentations. In fact, they will be ready to pepper you with questions. Each student who is not presenting during a given class session is responsible to (1) read, on Blackboard, the primary material for that day’s four presentations and (2) prepare two discussion questions (per instructions below) for each person presenting.

Each presentation will have four parts, described below, which will work together to help your classmates (your “adult Sunday school class”) get the most out of the primary-source materials they have read for that day. How you divide these four areas among the members of your panel is up to you. You will be graded on how well your presentation achieves the goals given in the following description of the “four parts”:

Presentations: The “four parts”

Think of your presentation as a mission to the “final frontier”—knowledge of the past:

I. “Prepare your launching pad”

Contextualize your writers and the movement or event they represent (e.g. Puritans, Vatican II) in social, cultural, and ecclesiological history.

0fd52cfd106dba7d68e58523a63fb839.doc HS502: Syllabus Page 6

What do I mean by social, cultural, and ecclesiological history?

a. Social: Give us a window into the economic, political, and demographic realities of the writers’ time, with special attention to (1) social realities that shaped the writers’ thinking and (2) social realities that can help us to understand what they were thinking and why. One good way of getting at these two aspects of a writer’s social context is to ask yourself: What made you say “aha!” when you were learning about the social background of that writer?

b. Cultural: Introduce us to trends of thought and practice in the social world of the writers, including any details about the arts, sciences, religious landscape, etc. that will help us to understand the writers and their thought.

c. Ecclesiological: Tell us what we need to know about the church setting in which the writers lived and thought. This can include theology, worship, ecclesiology, social ministry, and whatever else is relevant to helping us understand the key quotations you have chosen to highlight from the primary document(s).

II. “Build and position your spacecraft”

Provide us (your Sunday school class) with a sturdy profile of the movement or event represented by your writers. What key facts will help us understand what this movement or event was all about? Are there important things we should know about the writers themselves? For this section, you may wish to provide the class with a handout or two: Timelines, chronologies, nutshell biographical sketches, charts or other visual aids, and brief bibliographies of key sources are all welcome. In this way, you can “resource” your colleagues (and perhaps some future adult Sunday school class that you’ll use this presentation with!), enriching their understanding of church history.

III. “Lift off and ‘boldly go!’”

Take a few well-chosen quotations from the primary source materials and explain to us what those ideas meant to the writers—and to their church and their society, given the historical context and description you’ve just set up for us. BIG points are given on this section for exercising your sympathetic historical imagination to get beyond modern stereotypes to what the writers really meant. What made them “tick”? In this section, I will be looking for a presentation of your writers’ ideas that, even if it is a critical one (that’s fine with me, as long as you proceed with appropriate sensitivity to classmates who may identify with the positions you are critiquing), would still be recognizable to them.

IV. “Bring the fruits of your exploration back to earth”

Now tell us what these writers’ ideas can mean for us today. Though you may be tempted to do this in sections I-III, resist that temptation. There’s no point in applying history to today if we rush through the history itself to get to the application—and thus do a bad job of the history. That would be like, well, getting into a rusty, decrepit rocket on a broken-down launch pad and trusting it to get us where we want to go! This section, though important, should take up no more than ¼ of your presentation.

0fd52cfd106dba7d68e58523a63fb839.doc HS502: Syllabus Page 7

HS502 presentation topics and primary readings

Topic Pages (B = Bettenson, P = Placher [Blackboard])

Roots and key documents of the B 202-33, 236-38 Reformation; reading only, no presentation

A. Anabaptists Hillerbrand, The Protestant Reformation, 122-152 (Blackboard)

B. Catholic Reformation: Institutional B 272-82; P 47-52; Profession and spiritual reform of Tridentine Faith

C. Puritanism B 311-19; P 75-79, 108-113; Selections from Puritan Writers

D. Quakers B 337-41; P 79-82; William Penn, A Letter to the King of Poland;

E. Deism; reading only, no B 341-49; P 83-87 presentation

F. Methodism; reading only, no B 349-51; P 94-98; John presentation Wesley, The Character of a Methodist

G. Evangelicalism; reading only, no P 111-114, 117-119, 165-167; presentation additional reading TBA

H. The Oxford Movement & the B 351-59; P 145-49; Gaustad Mercersburg Theology vol. I, 422-24

I. Liberalism P 131-39, 149-51, 169-74; Gaustad vol. II, additional reading TBA

J. Vatican II B 359-369

K. New voices (black, liberation, B 375-390; P 200-205 (P is feminist, and eco- theology) optional)

0fd52cfd106dba7d68e58523a63fb839.doc HS502: Syllabus Page 8

HS502 presentation discussion questions

Each week that there are presentations, every student in the class will read—at least skim- read, to familiarize themselves with—the primary material listed in the right-hand column of the presentation grid, p. 7 in this syllabus. Then, some time before the class, you will post two questions on the appropriate forum(s) in the Blackboard “Discussion board” area. (that's 2 questions per week, not per presentation topic). Then print a copy of your questions to refer to during the presentations.

Your two discussion questions—one in each of two categories—should be questions that you would honestly like answered about each set of readings. The purpose of these questions is to contribute to our class discussion. In framing each of your two kinds of questions (1 & 2, below), you may also add to the question a brief comment suggesting your own tentative answers or observations on these questions. But these comments shouldn’t go beyond a sentence or two— and there must be a real question behind them! Each discussion week, I will be looking for one discussion question from each student, for each presentation, in each of the following categories:

1. A question of fact For example, you may ask: “What does such-and-such a word in the reading mean?” or “Did people in the writer’s time pay any attention to such-and-such a recommendation of his/hers?” or “Such-and-such an event, social practice, or statement seems bizarre, stupid, self-contradictory or otherwise opaque to my modern American understanding. Is there some piece of historical background knowledge that would explain this?” You could also ask many other kinds of questions of fact—as long as they (1) will help illuminate the text for you and perhaps others in the class, and (2) can be answered in a straightforward, factual mode.

2. A question of interpretation Please read the following carefully:

Your interpretive questions must be fruitfully discussable—or in other words, non-trivial.

First, to be discussable and non-trivial, your interpretive question must not lead to a dead end because it is unanswerable from the text. So the question, “Did John Wesley secretly desire to overthrow the government of England?” or the question, “Would John Wesley have espoused Confucian thought?” are both trivial questions because there’s no way to answer either of them from the text. Any answer we might give would be conjecture or would require some other source text or piece of evidence we don’t have. Note that a “trivial” question in this sense is not necessarily an un-important one—just not useful for discussion.

Second, to be discussable and non-trivial, your interpretive question must not lead to an immediate, obvious answer. So, “Did John Wesley really believe a good Methodist ought to be happy all the time?” would also be trivial because we can immediately answer the question from the text. Again, “trivial” in this sense does not mean un-important, just not useful.

One possible non-trivial interpretive question on Wesley would be this one: “Why did Wesley pose ‘happiness’ as a key marker of a good Methodist?” Though the presenter may not have an immediate answer to this question, it could spark a good discussion that would draw not only on the text itself, but on the social, cultural, and ecclesiological context and the profile of Wesley

0fd52cfd106dba7d68e58523a63fb839.doc HS502: Syllabus Page 9 and his movement that the presenter will have given us. Such a discussion could help us work toward important truths about Wesley and his Methodist movement.

Note that I say we work toward the truth about Wesley. I don’t believe we can ever come to the definitive, complete, comprehensive, water-tight truth about this or any other important question related to history. It’s the Law of Diminishing Certainty: the more important and “deep” the question, the harder it is to get a single, simple, conclusive answer.

This may discourage those of you who come to the study of history on a quest for objective truth —defining truth in strong modernist terms as absolute certainty. Or it may confirm those of you with tendencies toward strong postmodernism in the opinion that history-writing is just “a joke we play on the dead”—imposing whatever fanciful interpretations we want to on the past, and let the most convincing orator (or the person with the bucks and the social power to publish the most books) win.

I now fall in neither of these extreme camps—though during my graduate studies I went through both of them. I’ve finally cast my lot with the Pietists. This is my position: If we ask good, meaty, non-trivial questions in our study of what human beings have said and done in history, we will learn useful, transformative things. In other words, history repays those who join its interpretive conversation: they come away better people for it.

In the end, for our purposes, the journey is, in a significant sense, the destination. That’s why we’re investing time in primary source reading, presentation, and discussion in this course: we’re learning how to become our own interpreters of history.

Final paper

Final paper will be 8-10 pp. (including any footnotes, but not title page or bibliography), due June 4, in a subtopic of one of the remaining 11 presentation topics that you did not choose to present on (including the topics without presentations: E, F, and G).

The assignment for the final paper is this: choose some narrow, limited subtopic (e.g. a particular person, idea, event, document, etc.) of your chosen topic that engages your interest, and write a paper that does the following:

(1) contextualizes that subtopic in a manner similar to part I of the presentations,

(2) profiles or explains, for the lay reader, your subtopic in a manner similar to part II of the presentations, and

(3) explains the relevance of that subtopic for us today, in a manner similar to part IV of the presentations.

0fd52cfd106dba7d68e58523a63fb839.doc