Chapter 4: Physical Development in Infancy

Learning Goals

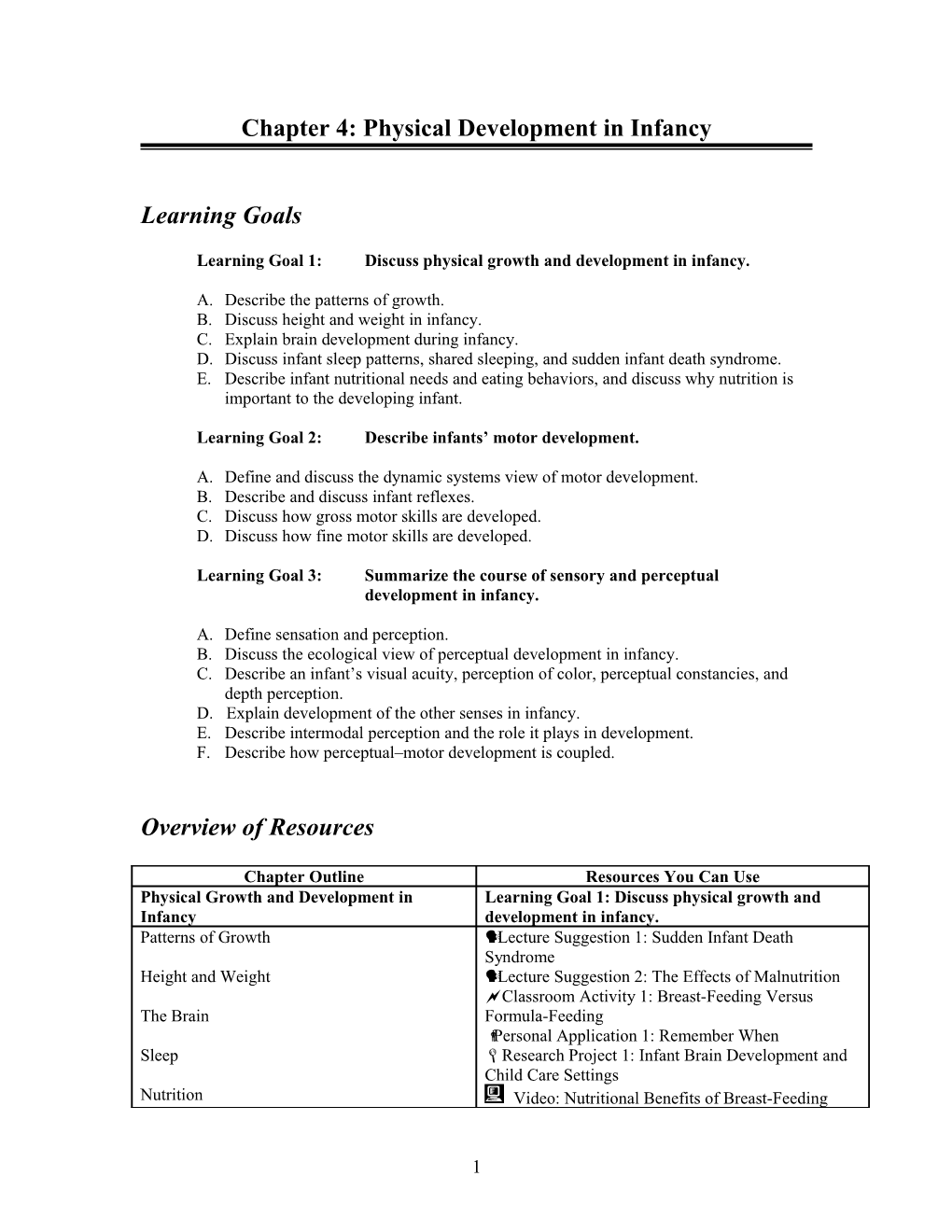

Learning Goal 1: Discuss physical growth and development in infancy.

A. Describe the patterns of growth. B. Discuss height and weight in infancy. C. Explain brain development during infancy. D. Discuss infant sleep patterns, shared sleeping, and sudden infant death syndrome. E. Describe infant nutritional needs and eating behaviors, and discuss why nutrition is important to the developing infant.

Learning Goal 2: Describe infants’ motor development.

A. Define and discuss the dynamic systems view of motor development. B. Describe and discuss infant reflexes. C. Discuss how gross motor skills are developed. D. Discuss how fine motor skills are developed.

Learning Goal 3: Summarize the course of sensory and perceptual development in infancy.

A. Define sensation and perception. B. Discuss the ecological view of perceptual development in infancy. C. Describe an infant’s visual acuity, perception of color, perceptual constancies, and depth perception. D. Explain development of the other senses in infancy. E. Describe intermodal perception and the role it plays in development. F. Describe how perceptual–motor development is coupled.

Overview of Resources

Chapter Outline Resources You Can Use Physical Growth and Development in Learning Goal 1: Discuss physical growth and Infancy development in infancy. Patterns of Growth Lecture Suggestion 1: Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Height and Weight Lecture Suggestion 2: The Effects of Malnutrition ~Classroom Activity 1: Breast-Feeding Versus The Brain Formula-Feeding Personal Application 1: Remember When Sleep LResearch Project 1: Infant Brain Development and Child Care Settings Nutrition Video: Nutritional Benefits of Breast-Feeding

1 Motor Development Learning Goal 2: Describe infants’ motor development. The Dynamic Systems View Lecture Suggestion 3: Current Views of Infant Motor Development Reflexes ~Classroom Activity 2: Assessing Infant Reflexes LResearch Project 2: Replication of Thelen’s Work Gross Motor Skills on Infant Motor Development Video: Gross Motor Ability At One Year Fine Motor Skills

Sensory and Perceptual Development Learning Goal 3: Summarize the course of sensory and perceptual development in infancy. What Are Sensation and Perception? ~Classroom Activity 3: To Circumcise or Not to Circumcise—That Is the Cutting Question The Ecological View Personal Application 2: If I Could Read Your Mind

Visual Perception

Other Senses

Intermodal Perception

Perceptual–Motor Coupling

Review ~Classroom Activity 4: Assessing Infant Abilities ~Classroom Activity 5: Critical-Thinking Multiple- Choice Questions and Answers ~Classroom Activity 6: Critical-Thinking Essay Questions and Suggestions for Helping Students Answer the Essays

Resources

Lecture Suggestions

Lecture Suggestion 1: Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Learning Goal 1: Discuss physical growth and development in infancy.

You may want to start this lecture by presenting the story of an infant who died from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) ( http://sids-network.org/stories.htm ). Then introduce students to the facts and myths regarding SIDS. Complete the lecture by presenting the current thinking about causes and lowering risks.

SIDS is:

2 a definite medical entity. experienced by seemingly healthy victims. a death that occurs quickly, with no signs of suffering, and is usually associated with sleep. currently unpredictable and not preventable. determined after a thorough investigation including an autopsy, a death scene investigation, review of the infant’s health status prior to dying, and other family medical history. the major cause of death in infants between 1 month and 1 year of age with most deaths occurring between the ages of 2 and 4 months. claims the lives of over 7,000 American babies each year…nearly one baby every hour of every day.

SIDS is not:

caused by external suffocation. caused by vomiting and choking. caused by child neglect or abuse. contagious.

Who is at risk for SIDS?

Babies who sleep on their stomachs. Babies born to mothers who smoke during pregnancy, and babies who are exposed to passive smoke after birth. Babies born to mothers who are younger than 20 years old at the time of their first pregnancy. Babies born to mothers who had no or late prenatal care. Babies who are premature or those with low birth weight. Babies who are placed to sleep on soft surfaces such as soft mattresses, sofas, sofa cushions, waterbeds, sheep skins, or other soft surfaces. Babies who are placed to sleep in an environment containing fluffy and loose bedding such as pillows, quilts, other coverings, stuffed toys, and other soft items.

What causes SIDS?

Evidence suggests that some SIDS babies are born with brain abnormalities that make them vulnerable to sudden death during infancy. In many SIDS babies, abnormalities are found in parts of the brainstem that use serotonin as a neurotransmitter and are thought to be involved in the control of breathing during sleep, sensing carbon dioxide and oxygen, and the ability to wake up. A baby with this abnormality may lack a protective brain mechanism that senses abnormal respiration or cardiovascular function and which would normally lead babies to wake up and take a breath.

Babies who sleep on their stomachs may get their faces caught in bedding, which causes them to breathe too much carbon dioxide and too little oxygen. Researchers are studying whether this is why sleeping on the stomach is hazardous, and why babies with brainstem abnormality die when sleeping in this position.

3 A larger number of babies who died from SIDS apparently had respiratory or gastrointestinal infections prior to their deaths. This fact may explain why more SIDS cases occur during the colder months of the year. Researchers indicate that some SIDS babies had higher-than-normal numbers of cells and proteins generated by the immune system. Some of these proteins interact with the brain to alter heart rate, slow breathing during sleep, or put the baby into a deep sleep which may be strong enough to cause death, particularly if the baby has an underlying brain abnormality.

What can parents and other caregivers do to lower the risk of SIDS?

Place babies to sleep on their backs unless advised otherwise by a physician. Place the baby on a firm mattress, such as in a safety-approved crib or other firm surface. Remove all fluffy and loose bedding, such as fluffy blankets or other coverings, pillows, quilts, and stuffed toys, from the baby’s sleep area. Get good prenatal care, including proper nutrition, avoid maternal smoking or drug/alcohol use, and go for frequent medical checkups beginning early in pregnancy. Take babies for regular well-baby checkups and routine immunizations.

Sources: http://sids-network.org/facts.htm http://www.prevent-sids.org/sids-facts.htm

Lecture Suggestion 2: The Effects of Malnutrition Learning Goal 1: Discuss physical growth and development in infancy.

The purpose of this lecture is to expand upon Santrock’s introduction of the effects of malnutrition. The prevalence of malnutrition is overwhelming. Nearly 195 million children under the age of 5 are undernourished. Malnutrition affects physical and cognitive development, and the environment in which malnutrition occurs also influences the outcome.

Brown and Pollitt’s (1996) article “Malnutrition, Poverty, and Intellectual Development,” overviews several interesting studies related to this complex relationship. Recent research has stimulated a conceptual shift in our understanding of the relationship between malnutrition and cognitive impairments. Traditionally, the “main-effect” model guided our understanding. This model states that malnutrition during the first two years of life caused severe, permanent brain damage that in turn resulted in cognitive impairment. This linear model is too simplistic: brain growth retardation is not always permanent. Rather, brain growth is “put on hold temporarily” when malnourished. If diet is improved, brain growth can rebound, especially if an appropriate environment is involved. In addition, other factors such as physical growth, quality of the environment, and intellectual stimulation impact the effects of malnutrition on cognitive development. Thus, an “interactional model” more accurately describes the complicated relationship between malnutrition and cognitive development. Malnutrition has a bidirectional relationship with illness which can cause delays in motor development and physical growth, which, in turn, leads to lowered expectations of the child from others; these lowered expectations can impede cognitive development. In parallel, delayed motor development and physical growth, and lethargy from illness can reduce exploration of the environment, which impacts cognitive development. If poverty is added to the equation, the effects can be exacerbated given the reduced quality of the environment in which the child can explore and the lack of educational and medical resources.

4 Source: Brown, J. L., & Pollitt, E. (1996). Malnutrition, poverty, and intellectual development. Scientific American, 274(2), 38–43.

Lecture Suggestion 3: Current Views of Infant Motor Development Learning Goal 2: Describe infants’ motor development.

The purpose of this lecture is to expose students to the current view of infant motor development. Esther Thelen’s dynamic systems theory is introduced in the chapter, and this lecture extension describes one of her research studies (1984; 1987; 1994). Thelen’s perspective contrasts sharply with traditional views of motor development which consider motor development as a maturationally determined stage-like progression. In contrast, Thelen views motor development and walking, in particular, to be the result of “self-organization.” That is, systems exhibit complex patterns over time without a genetic blueprint. Movement develops from the interaction of constraints in the organism and the environment. Thus, it is the dynamic interaction of developing neuromuscular pathways and changing environmental demands that determines when an infant will first walk independently. This new view of motor development emphasizes the importance of exploration and selection in finding solutions to new task demands. Infants need to assemble adaptive patterns by modifying their current movement patterns. The task and the challenge of the context are what drive change, not prescribed genetic instructions.

The so-called disappearing reflex intrigued Thelen. Newborn infants, when held upright with their feet on a support surface, perform alternating step-like motions and appear to be walking. This phenomenon is referred to as the “stepping reflex.” The intriguing aspect of this is that this ability “disappears” a few months later and does not reappear until approximately 12 months of age. Experts assumed that the reflex “disappears” because of some genetic maturationally determined switch in the brain. This explanation made sense because they assumed that motor development was single-causal. However, Thelen and her colleagues (1984) observed infants kicking their legs and noted that they were actually engaged in the same movement as the stepping reflex. Thus, the kicking movement was actually the stepping reflex in a supine position. Interestingly, when they positioned the kicking infant in an upright position, the infant ceased the motion, yet when they laid the same infant down, the infant resumed the kicking/stepping movement. They questioned how the maturing brain could inhibit this reflex in one position and not in a different position.

During the same developmental period that the stepping reflex was not evident in the upright position (after it disappears), Thelen noted that infants were experiencing rapid weight gain. The infants were getting heavier, but not necessarily any stronger. She then speculated that it was the interaction of the heavier legs and the biomechanically demanding posture of being upright that suppressed the stepping reflex. Thelen and her colleagues ingeniously tested their hypothesis (Thelen, Fisher, & Ridley-Johnson, 1984). They experimentally manipulated the weight of the infants’ legs by submerging the infants in waist-deep water. The infants, without the added weight, could “walk.” The point to stress is that motor development is not single-causal, but rather a multicausal developmental phenomenon.

Research Project 2 (Replication of Thelen’s Work on Infant Motor Development) complements this lecture suggestion.

Sources:

5 Thelen, E. (1994). Motor development: A new synthesis. American Psychologist, 50, 79–95. Thelen, E., Fisher, D. M., & Ridley-Johnson, R. (1984). The relationship between physical growth and a newborn reflex. Infant Behavior and Development, 7, 479–493. Thelen, E., Kelso, J. S., & Fogel, A. (1987). Self-organizing systems and infant motor development. Developmental Review, 7, 39–65.

~Classroom Activities

Classroom Activity 1: Breast-Feeding Versus Formula-Feeding Learning Goal 1: Discuss physical growth and development in infancy.

This activity is designed to stimulate discussion regarding students’ knowledge and perceptions of breast-feeding and bottle-feeding. This activity would be useful in introducing the topic of infant nutrition. Pass out Handout 1, and have students take five minutes to complete the survey.

Count the percentage of students who were breast-fed versus formula-fed.

Ask students to share if they have ever heard their mother or caretaker talk about their feeding experience from when the student was an infant. If so, what have they heard them say? Most of the students in the class may not have ever spoken with their mother or caretaker about this topic (it tends to come up only when a new child or grandchild is on the way).

Create a class list of advantages and disadvantages of breast-feeding and bottle-feeding. It is often interesting to hear what the male students say, and you may notice trends in what the women versus the men say. The men in the class often comment that whatever their preference, it may not be their choice whether or not their wife or partner breast-feeds their baby.

Classroom Activity 2: Assessing Infant Reflexes Learning Goal 2: Describe infants’ motor development.

The purpose of this classroom activity is twofold: (1) students will gain experience assessing infant reflexes; and, (2) students will further develop their understanding of infant reflexes. The goal is to assess two infants, one aged 1 to 4 months and the other aged 6 to 12 months. Invite two parents and their infants to class. Oftentimes, one of your students has an infant in his or her family or knows someone who does; most often a phone call is all it takes to get the parent to bring the baby to the class. Handout 2 describes seven infant reflexes and the conditions that elicit each of the reflexes. For each infant, have the parent perform the stimulation necessary to elicit the reflexive behavior. Students can note on the handout which of the reflexes are present (P) or absent (A) for each infant. After performing the demonstration with each infant, they should answer the questions that are listed in Handout 2.

Use in the Classroom: Discuss the observation techniques and possible problems with the methods used. Have students discuss any discrepancies and the reasons why reflexes drop out.

Logistics: Materials: Handout 2 (Assessing Infant Reflexes).

6 Group size: Full class. Approximate time: 10 minutes for the reflex assessment and 15 minutes for a full class discussion.

Classroom Activity 3: To Circumcise or Not to Circumcise—That Is the Cutting Question Learning Goal 3: Summarize the course of sensory and perceptual development.

This activity affords students an opportunity to debate the controversy surrounding infant circumcision. Oftentimes, students have preformed ideas regarding circumcision or neglect to consider the implications of circumcision. Students usually assume that circumcisions are only performed on male infants. In small groups, have students identify the advantages and disadvantages of male circumcision and the advantages and disadvantages of female circumcision. Also, the groups should determine whether they are in favor of male and female circumcision. Frequently, students in the United States are appalled by the practices of female circumcision in Africa, yet they fail to reflect on the practice of male circumcision in the United States. Then as a class, you can tally the groups’ ideas, positions, and the mitigating circumstances for whether they would encourage the circumcision of male and female infants. Do the students’ decisions differ based upon gender, age, religion, or parenting status? The following ideas will help you get started:

According to Kennard (2004), current rates for male circumcision are as follows:

Australia 15% Canada 20% United States 60%

In the United States, over 1.25 million infants are circumcised annually (3,300 per day, 1 child every 26 seconds).

Advantages of male circumcision: Parents can make sure that after-surgery care is properly done to avoid infection. Parents can request safe local anesthesia for the baby during the procedure. Circumcised males have easier hygiene to practice. Circumcised men are less likely to contract cancer of the penis.

Disadvantages of male circumcision: Surgery has a little risk, as do all surgeries; after-surgery care is important for avoiding infection. Physical trauma occurs because most circumcisions are performed without anesthesia. There is no evidence that a circumcised male is less likely to acquire or transmit venereal disease. Cancer of the penis is quite rare.

Two interesting films related to female genital mutilation: Warrior Marks by Alice Walker: This is a documentary film that follows Alice Walker and Pratibha Parmar through a journey in Africa and England, where they seek to educate people about the harmful, sometimes deadly aftereffects of female genital mutilation. Rites, a documentary film by the American Anthropological Association (AAA), also outlines the harmful effects of female genital mutilation.

For additional information and perspectives, visit the following Web sites:

7 http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/ http://www.fgmnetwork.org/intro/fgmintro.html

Logistics: Group size: Small group, then full class. Approximate time: Small group (15 minutes) and full-class discussion (30 minutes).

Sources: Denniston, G. C. (1992). Unnecessary circumcision. The Female Patient, 17. Kennard, J. (2004). Male circumcision. http://menshealth.about.com/cs/menonly/a/circumcision.htm Romberg, R. (1985). Circumcision: The painful dilemma. South Hadley, MA: Bergin & Garvey Publishers. Squires, S. (June 1990). Medinews. Ladies’ Home Journal, 94.

Classroom Activity 4: Assessing Infant Abilities Learning Goal 2: Describe infants’ motor development. Learning Goal 3: Summarize the course of sensory and perceptual development.

The purpose of this activity is to expose students to an infant, and allow them to observe an assessment of an infant’s abilities. Invite a parent and his or her infant to class. Oftentimes, one of your students has an infant in his or her family or knows someone who does; most often a phone call is all it takes to get the parent to bring the baby to the class. It is important to demonstrate various infant assessment instruments or scales to the students before the infant is brought into the class. Consider covering the Apgar, the Brazelton Neonatal Assessment Scale, and the Denver Developmental Screening Test. If the psychology department, educational psychology department, or library does not have a copy of these screening devices, a local pediatrician may be convinced to part with a copy of what they use and to offer some quick instruction on how to use it. Another option is to invite a local pediatrician to come to the class and give the screening.

The students’ task will be to determine the age of the infant as well as the baby’s developmental scores. It is best if each student gets a copy of the screening devices ahead of time. During the class period, run the infant through some of the components of each of the screening devices. It would probably be best if you conducted the behavioral tests, but only upon the direction of the students. The infant will experience less stress if you minimize the number of individuals manipulating him or her. The infant, if awake, will tolerate between 10 and 20 minutes of manipulation. After the infant leaves or refuses to play anymore, have students try to determine what the baby’s scores would be on the various measures and to give their best guess as to the specific age of the infant. Ask the parent to reveal the infant’s actual age and, if known, the baby’s latest developmental scores. If the infant is unresponsive during the class period, allow the students to ask the parent questions regarding the infant (e.g., can he or she differentiate the infant’s cries).

Logistics: Materials: One or more of the following assessment instruments: Apgar, Brazelton Neonatal Assessment Scale, and Denver Developmental Screening Test. Copies of the screening devices for students. Group size: Full class. Approximate time: 20 minutes to review assessment devices, 10 to 20 minutes for the assessment, and 30 minutes for a full-class discussion.

8 Classroom Activity 5: Critical-Thinking Multiple-Choice Questions and Answers Learning Goal 1: Discuss physical growth and development in infancy. Learning Goal 2: Describe infants’ motor development. Learning Goal 3: Summarize the course of sensory and perceptual development.

Discuss the answers to the critical-thinking multiple-choice questions in Handout 3. Suggested answers are provided in Handout 4.

The point of question 1 is to get students to pay attention to figures and tables provided in the text. Students often do not understand this material very well; you probably will want to discuss how to interpret tables and figures with them. For example, you may want to address how inferences can be drawn from the tables and figures beyond what is indicated in text or captions.

The point of question 2 is to have students attend to the difference between sensation and perception, and to examine the sorts of inferences researchers make about infant perceptual capacities based on infant behavior. Both of these issues are good topics for discussion prior to having students do this exercise. The distinction between sensation and perception is not clear to people working in the field, and some researchers do not feel it is productive to make the separation. Nevertheless, an interesting way to apply the distinction is to discuss whether infants’ discrimination between stimuli, or their reaction to stimulating events, represents some sort of innate, reflexive response or whether it is based on active interpretation. You can guide students’ solutions to this question by having them try to decide which of the results for each of the senses described in the text most convincingly indicates active perceptual processes.

Question 3 continues to provide practice with the distinctions between inferences, observations, and assumptions.

Logistics: Materials: Handout 3 (Critical-Thinking Multiple-Choice Questions) and Handout 4 (Answers). Group size: Small groups to discuss the questions, then a full-class discussion. Approximate time: Small groups (15 to 20 minutes), full-class discussion of any question (15 minutes).

Classroom Activity 6: Critical-Thinking Essay Questions and Suggestions for Helping Students Answer the Essays Learning Goal 1: Discuss physical growth and development in infancy. Learning Goal 2: Describe infants’ motor development. Learning Goal 3: Summarize the course of sensory and perceptual development.

Discuss students’ answers to the critical-thinking essay questions presented as Handout 5. The purpose is threefold. First, answering these questions further facilitates students’ understanding of concepts in chapter 4. Second, this type of essay question affords the students an opportunity to apply the concepts to their own lives which will facilitate their retention of the material. Third, the essay format also will give students practice expressing themselves in written form. Ideas to help students answer the critical thinking essay questions are provided as Handout 6.

Logistics: Materials: Handout 5 (Essay Questions) and Handout 6 (Ideas to Help Answer).

9 Group size: Individual, then full class. Approximate time: Individual (60 minutes), full-class discussion of any questions (30 minutes).

Personal Applications

Personal Application 1: Remember When Learning Goal 1: Discuss physical growth and development in infancy. Learning Goal 2: Describe infants’ motor development. Learning Goal 3: Summarize the course of sensory and perceptual development.

The purpose of this exercise is for students to connect with the material on infant development through stories about themselves. Since we have no active memories dating back to our first couple of years, it is not possible to recall experiences related to reflex-based functioning, milestones such as rolling over and searching for a hidden object, and parental responses. The dramatic nature of development during these early stages is difficult to grasp when simply reading about it in a book.

Instructions for Students: Ask your parents to spend some time talking with you about when you were a baby. Maybe they can get out the pictures and your baby book. Ask them what they remember about the early days after birth. Did your mother breast-feed or not? Why? What were the views during that time about doing so? What are their memories of your sleep habits, eating habits, motor development, crying, stimulus response, and potty training? In what ways do they remember you changing the most? Enjoy this walk down memory lane with your parents and either read your text prior to your conversation or soon afterward to link your own story with the specific developmental issues covered.

Use in the Classroom: Have students share their stories in class. Compare and contrast what they experienced and discuss how much is likely to indicate individual differences and how much is a function of their parents’ memories.

Personal Application 2: If I Could Read Your Mind Learning Goal 3: Summarize the course of sensory and perceptual development.

The purpose of this exercise is to get students to think more in depth about infant sensory experiences and the research methods used to study them. Until quite recently, babies have been believed to experience the world in very limited ways. This was most likely because people relied only on what they could see babies do. Some amazing developments have been made with regard to assessing the early experiences of infants, and we now know that even in utero, babies are capable of sensing and encoding sensory information.

Instructions for Students: Read through your text and familiarize yourself with infants’ sensory functioning and the studies psychologists have done to learn more about this amazing area. Choose a behavior you would like to explore with an infant, and write up how you would go about studying it. Use a journal article format to write up your proposal, beginning with the behavior of interest, why it is of interest, and your methodology. Base your results section on what you expect you might find, and conclude with any questions you may have that would lead to additional scientific investigation.

10 LResearch Project Ideas

Research Project 1: Infant Brain Development and Child Care Settings Learning Goal 1: Discuss physical growth and development in infancy.

The purpose of this activity is to have students review research studies regarding infant brain development and to apply the research findings to the development of an infant child care setting. The first step involves the literature review. Either have students gather research articles or you can have a few selected articles for the students to use. Nash’s (1997) article “Fertile Minds” in Time magazine is very interesting and relevant. In small groups, the students should then generate a list of perceptual abilities that develop over the first year of life. Second, the students should develop a child care program for infants that would facilitate infants’ brain development. The child care program should be based on suggestions from current research findings that would enhance infants’ development. For example, they should determine what toys would be appropriate for infants of different ages, and they should decide how they would decorate the setting. Consider using Gunzenhauser’s (1988) edited book as a resource for this activity. It is important to point out that more stimulation is not always better. See Handout 7.

Have students complete the following tasks: First, using research articles and your textbook, identify how the brain develops during the first year of life. Explain how experiences influence brain development. Second, develop a child care program for infants that would facilitate infant brain/perceptual development. The child care program should be based on suggestions from current research that would enhance infants’ development. For example, you will want to consider what toys would be appropriate for infants of different ages and decide how you would decorate the setting.

Sources: Gunzenhauser, N. (1988). Infant stimulation: For whom, what kind, when, and how much? (Pediatric Round Table No. 13). Johnson & Johnson Baby Products. Nash, J. M. (1997, Feb. 3). Fertile minds. Time, 49–56.

Research Project 2: Replication of Thelen’s Work on Infant Motor Development Learning Goal 2: Describe infants’ motor development.

This research project will help students understand the complex nature of the development of infant motor skills, especially the development of walking, and give them practice replicating a research study. Lecture Suggestion 3 regarding Thelen’s perspective on infant motor development will provide relevant background knowledge. This project will require approval by the school’s human subjects review board and the parent’s informed consent.

First, have students read the Thelen, Fisher, and Ridley-Johnson (1984) article. They should also write a summary of the introduction and specify the hypotheses. Second, have students, in groups of two to four people, replicate the procedure in this study. Given that two separate manipulations were conducted in the Thelen, Fisher, and Ridley-Johnson study, have half of the students manipulate the leg mass by adding small weights to the infant’s legs. The other half of the class can manipulate the effects of leg mass by submerging the infant’s legs in water. Third, students should write up their results and relate their results to the hypotheses. If the results are not

11 consistent with Thelen’s, have the students explain why they think the results were inconsistent. Finally, students should present their findings to the class. See Handout 8.

Use in the Classroom: Discuss whether the students had to modify the procedures. Did they obtain the same findings? If not, why?

Source: Thelen, E., Fisher, D. M., & Ridley-Johnson, R. (1984). The relationship between physical growth and a newborn reflex. Infant Behavior and Development, 7, 479–493.

Videos

VAD segment # 1708: Nutritional Benefits of Breast-Feeding (found on the Online Learning Center, www.mhhe.com/santrockld13)

Human milk or an alternative formula is the baby’s source of nutrients and energy for the first 4 to 6 months of life. For years, debate has focused on whether breast-feeding is better for the infant than bottle-feeding, but studies have shown that breast-feeding is better for many important health reasons.

VAD segment #828: Gross Motor Ability at 1 Year (found on the Online Learning Center, www.mhhe.com/santrockld13)

Gross motor skills involve large-muscle activities such as moving one’s arms and walking. Key skills developed during infancy include control of posture and walking. A number of gross motor milestones occurs in infancy, although the actual timing of milestone achievement may vary as much as 2 to 4 months, especially in older infants. Although infants usually learn to walk by their first birthday, the neural pathways that allow walking begin to form earlier.

McGraw-Hill's Visual Assets Database for Life-span Development (VAD 2.0) (http://www.mhhe.com/vad) This is an on-line database of videos for use in the developmental psychology classroom created specifically for instructors. You can customize classroom presentations by downloading the videos to your computer and showing the videos on their own or inserting them into your course cartridge or PowerPoint presentations. All of the videos are available with or without captions.

Multimedia Courseware for Child Development Charlotte J. Patterson, University of Virginia This video-based two-CD-ROM set (ISBN 0-07-254580-1) covers classic and contemporary experiments in child development. Respected researcher Charlotte J. Patterson selected the video and wrote modules that can be assigned to students. The modules also include suggestions for additional projects as well as a testing component. Multimedia Courseware can be packaged with the text at a discount.

McGraw-Hill also offers other video and multimedia materials; ask your local representative about the best products to meet your teaching needs.

12 Feature Film

In this section of the Instructor's Manual, we suggest films that are widely available from local video rental outlets.

Jack (1996)

Starring Robin Williams, Diane Lane Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

This fun but dramatic film is about a boy with a unique aging disorder that makes him age four times faster than normal children. Various problems ensue such as going to school for the first time and trying to become friends with children his age, causing emotional stress, and not just physical issues, for young Jack.

üWeb site Suggestions

At the time of publication, all sites were current and active; however, please be advised that you may occasionally encounter a dead link.

American SIDS Institute http://www.sids.org/

Circumcision Information and Resource Pages (CIRP) http://www.cirp.org/

Infant Senses http://life.familyeducation.com/baby/sensory-integration/50444.html

La Leche League International (Breastfeeding) http://www.lalecheleague.org/

Malnutrition http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/985140-overview

National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome http://www.dontshake.org/

National SIDS/Infant Death Resource Center http://www.sidscenter.org/

Zero to Three: National Center for Infants, Toddlers, and Families http://www.zerotothree.org/

13 Handout 1 (CA 1)

Breast-feeding Versus Formula-Feeding

How were you fed as an infant?

Breast-fed Bottle-fed (formula) Don’t know

List five advantages of breast-feeding.

List five potential disadvantages or concerns about breast-feeding.

List five advantages of formula-feeding.

List five potential disadvantages or concerns about formula-feeding.

If you have a child, or if you were to have a child, how would you want your child fed as an infant?

Breast-feeding Formula-feeding Don’t know

Why?

14 Handout 2 (CA 2) Assessing Infant Reflexes

The purpose of this exercise is twofold: (1) you will gain experience assessing infant abilities; and, (2) you will further develop your understanding of infant reflexes. The goal is to assess two infants, one aged 1 to 4 months and the other aged 6 to 12 months. For each infant, perform the stimulation necessary to elicit the reflexive behavior. Note which reflexes are present (P) or absent (A) for each infant. After completing the assessments, answer the questions that follow.

Infant 1 Infant 2 Reflex Stimulation and reflex Sex __ Age __ Sex __ Age __

Placing Place backs of infant’s feet against a flat surface’s edge: Baby withdraws foot P/A P/A

Walking Hold baby under arms with bare feet touching flat surface: Baby makes step-like motions that appear like coordinated walking P/A P/A

Darwinian Stroke palm of infant’s hand: (grasping) Baby makes strong fist; if both fists are closed around a stick, the infant could be raised to standing position P/A P/A

Tonic neck Lay baby down on back: Infant turns head to one side and extends arms and legs on preferred side and flexes opposite limbs P/A P/A

Moro (startle) Make a sudden, loud noise near infant: Infant extends legs, arms, and fingers; arches back; and draws back head P/A P/A

Babinski Stroke sole of baby’s foot: Infant’s toes fan out and foot twists in P/A P/A

Rooting Stroke baby’s cheek with one’s finger: Baby’s head turns, mouth opens, and sucking movements begin P/A P/A

Questions: How many of the reflexive behaviors were exhibited by each infant? Which reflexes dropped out early? What responses seem to replace each of the reflexive behaviors in the older infant? What might be the adaptive value of each reflex in the infant’s repertoire?

15 Handout 3 (CA 5)

Critical-Thinking Multiple-Choice Questions

1. Chapter 4 contains a number of tables and figures that illustrate various topics. Five of them are listed below. Each of the figures is paired with an interpretation of the information it presents. Which interpretation is most accurate? Circle the letter of the best answer, and explain why it is the best answer, and why each other answer is not as good.

a) Figure 4.6: The number of brain cells increases dramatically during the first two years of life. b) Figure 4.13: Reflexes that disappear involve gross motor behavior. c) Figure 4.15: Most infants can walk by themselves before they are 1 year old. d) Figure 4.5: Dendrites are located within the nucleus of the cell body. e) Figure 4.7: The synaptic density of the human brain peaks before 6 years of age and declines steadily up to age 11.

2. In this chapter, Santrock distinguishes between the concepts of sensation and perception, and then takes the reader on a tour of the sensory and perceptual capacities of human infants. For which sense do we appear to know the most about the perceptual capabilities of infants? Circle the letter of the best answer, and explain why it is the best answer and why each other answer is not as good.

a) vision b) hearing c) smell d) taste e) touch

3. Robert Fantz’s pioneering study of visual perception found that infants look at different things for different lengths of time. Which of the following statements represents an important inference rather than an assumption or an observation? Circle the letter of the best answer, and explain why it is the best answer, and why each other answer is not as good.

a) Infants, as young as 2 days old, prefer to look at patterns—such as faces, printed matter, or bull’s-eyes—longer than colored discs. b) Infants, as young as 2 days old, look longer at patterns—such as faces, printed matter, or bull’s-eyes—than they do at colored discs. c) Pattern perception has an innate basis. d) Fantz’s “looking chamber” advanced the ability of researchers to investigate infant vision perception. e) 2 month-old infants prefer to look at patterns—such as faces, printed matter, or bull’s-eyes—longer than colored discs.

16 Handout 4 (CA 5)

Answers for Critical-Thinking Multiple-Choice Questions

1. Chapter 4 contains a number of tables and figures that illustrate various topics. Five of them are listed below. Each of the figures is paired with an interpretation of the information it presents. Which interpretation is most accurate? Circle the letter of the best answer, and explain why it is the best answer and why each other answer is not as good.

a) The interpretation of figure 4.6 is not accurate. This figure illustrates the increasing richness of connections between neurons, not an increase in the number of neurons. Dendrites connect neurons, they are not separate nerve cells. b) The interpretation of figure 4.13 is not accurate. The grasping reflex involves fine, not gross, motor skills. c) The interpretation of figure 4.15 is not accurate. The figure shows a time range during which infants begin to walk unaided. This time frame extends well past 1 year of age. d) The interpretation of figure 4.5 is not accurate. Dendrites extend out from the cell body. They are not located within the nucleus of the cell body. e) The interpretation of figure 4.7 is accurate. The data presented in the figure reveals that all three regions of the brain show a dramatic increase in synaptic density by age 6 and then a steady decline up until age 11.

2. In this chapter, Santrock distinguishes between the concepts of sensation and perception, and then takes the reader on a tour of the sensory and perceptual capacities of human infants. For which sense do we appear to know the most about the perceptual capabilities of infants? Circle the letter of the best answer, and explain why it is the best answer, and why each other answer is not as good.

a) Vision is the best answer. We know of several kinds of visual discriminations that infants can make (e.g., striped versus gray fields, stages of face perception, depth perception, and coordination of vision and touch). These all seem to require different kinds of interpretations of visual stimuli and involve a greater variety of interpretations compared with the other senses. b) Hearing is not the best answer. Facts are presented about auditory discrimination, the coordination of hearing and vision, and hearing sensitivity. The first two are arguably aspects of perception, but the last seems more an example of sensation (registering the occurrence of a stimulus). So “vision” is a better answer. c) Smell is not the best answer. We know about a small number of smell discriminations that infants can make (perceptions). We have fewer examples of olfactory perceptions than visual perceptions. d) Taste is not the best answer. Again, we mainly know about various discriminations that are possible. Some of these discriminations, however, appear to be based on responses newborns make to very specific taste stimuli which may indicate that “true” perception is not involved. e) Touch is not the best answer. Much of the information about touch comes from studies of reflexes; hence, it is unclear whether perception is involved. Nothing is indicated about touch discriminations, and the only perceptual phenomenon noted is the coordination of touch and vision.

3. Robert Fantz’s pioneering study of visual perception found that infants look at different

17 things for different lengths of time. Which of the following statements represents an important inference rather than an assumption or an observation? Circle the letter of the best answer, and explain why it is the best answer and why each other answer is not as good. a) Infants, as young as 2 days old, prefer to look at patterns—such as faces, printed matter, or bull’s-eyes—longer than colored discs is not the best answer, as it is an assumption. Researchers assume that a preference is displayed when an infant looks longer at one stimuli compared with other stimuli. b) Infants, as young as 2 days old, look longer at patterns—such as faces, printed matter, or bull’s-eyes—than they do at colored discs is not the best answer as it is an observation. Fantz found that infants did look longer at patterns compared to colored discs. c) Pattern perception has an innate basis is the best answer as it represents an inference. Given that it is not possible to determine if pattern perception is innate, researchers infer that it is innately based or at least is acquired after only minimal environmental experience given that pattern perception has been observed in infants only 2 days old. d) Fantz’s “looking chamber” advanced the ability of researchers to investigate infant vision perception is not the best answer as it reflects an observation. Fantz’s pioneering work has stimulated significant research and understanding of infant visual perception. e) 2 month-old infants prefer to look at patterns—such as faces, printed matter, or bull’s-eyes—longer than colored discs is not the best answer as it is an assumption, same as the answer for “a.”

18 Handout 5 (CA 6)

Critical-Thinking Essay Questions

Your answers to these kinds of questions demonstrate an ability to comprehend and apply ideas discussed in this chapter.

1. Provide examples of cephalocaudal and proximodistal patterns of development.

2. Outline brain development during infancy, and speculate how brain development relates to behavioral and psychological development during this period of life.

3. How would you describe infant sleeping patterns to an expectant mother?

4. Discuss the pros and cons of breast- versus bottle-feeding.

5. How would you explain the importance of reflexes and their development to a friend?

6. Describe the general patterns in the development of infant motor capabilities during the first year.

7. Compare and contrast the development of gross and fine motor skills during infancy.

8. Describe the dynamic systems view proposed by Thelen, and explain how it differs from the traditional view of motor development.

9. Define and distinguish sensation and perception. Also, explain why they make interesting problems for study by developmentalists and what practical problems their study might solve.

10. Explain how it is possible for researchers to study infants’ early competencies.

11. Apparently, infants can imitate facial expression almost at birth, but have 20/200 to 20/400 vision at birth. Provide a rationale for understanding this apparent inconsistency.

12. Explain what we know about the ability of infants to hear.

13. Do infants feel pain? In answering, also indicate evidence that challenges the traditional practice of not administering anesthetics to infants having operations.

14. Describe the relationship between perception and motor development. Give an example.

19 20 Handout 6 (CA 6)

Ideas to Help You Answer Critical-Thinking Essay Questions

1. Present your examples in a directional format by following the flow of each pattern of development.

2. Approach these areas as a hierarchy—begin with brain development and map out behavioral development and then psychological development.

3. If you can, use infants you know to give examples of infants’ sleep patterns. Emphasize the similarities and differences between the infants.

4. Imagine that your job is to objectively inform mothers-to-be about their feeding options, keeping in mind that their concern is for what is in the best interest of their baby.

5. Begin by defining what a reflex is, then explicitly describe several infant reflexes. Tell the purpose of each, and then conclude with the overall importance of reflexes early in development.

6. Create a timeline, and mark the general onset of particular motor capabilities. Draw your conclusions about the overall patterns that emerge.

7. Make a list of gross motor skills and fine motor skills in the order in which they develop to provide an illustration of what you are comparing. You can derive similarities and differences from this.

8. Begin with an overview of the traditional view of motor development and its weaknesses. Describe dynamics systems theory and how it addresses the shortcomings of the former.

9. Describe what an individual experiences with regard to sensation and perception. This will provide a basis for explaining why they are pertinent to study, and the possible practical applications resulting from doing so.

10. Address this issue through descriptions of several infant research methodologies. Describe a study or two and the findings they have yielded. What factors contribute to our confidence in those results? What makes these studies (and their findings) different from those done years ago? Are infants getting smarter, or are the research methods getting better? Comment.

11. Examine the pictures in your text demonstrating infants’ visual abilities. Also review what the text says about the extent to which infants imitate, and the kinds of expressions they copy.

12. During your explanation, keep in mind the fact that infants cannot tell us what they can and cannot perceive. Also, address how we know what we do about their auditory experiences.

13. Begin with a discussion of the historical view of infants and pain. Why has thinking changed, and in what ways is it different? What practical implications have resulted from the change?

14. First define perception and explain what constitutes motor development—this will lay the foundation for a discussion about their relationship. The best explanations come out of approaching your audience as being completely naïve about the subject matter.

21 Handout 7 (RP 1)

Infant Brain Development and Child Care Settings

The purpose of this activity is to review research studies regarding infant brain development and to apply the research findings to the development of an infant child care setting.

Using research articles and/or your textbook, describe how the brain develops during the first year of life. Explain how experiences influence brain development.

Develop a child care program for infants that would facilitate infant brain/perceptual development. The child care program should be based on suggestions from current research findings that would enhance infants’ development. For example, you will want to consider what toys would be appropriate for infants of different ages, and decide how you would decorate the setting. It is important to point out that more stimulation is not always better.

Sources: Gunzenhauser, N. (1988). Infant stimulation: For whom, what kind, when, and how much? (Pediatric Round Table No. 13.) Johnson & Johnson Baby Products. Nash, J. M. (1997, Feb. 3). Fertile minds. Time, 49–56.

22 Handout 8 (RP 2)

Replication of Thelen’s Work on Infant Motor Development

The purpose of this research project is to help you better understand the complex nature of the development of infant motor skills, especially the development of walking, and to give you practice replicating a research study. In order to proceed, you will need to clear this project with the human subjects review board at your school and get a signed informed consent form from the baby’s parents. You will first write a summary of the Thelen, Fisher, and Ridley-Johnson (1984) article. Then you should attempt to replicate the procedure in this study. Half of the class will manipulate the infant’s leg mass by adding small weights to the infant’s legs. The other half of the class will manipulate the effects of leg mass by submerging the infant’s legs in water. You will then write up your results and relate the results to the proposed hypotheses. If the results are not consistent with those of Thelen, Fisher, and Ridley-Johnson, you should explain why you think the results were different.

Summarize the introduction section of the Thelen, Fisher, and Ridley-Johnson (1984) article. Identify the hypotheses of the study. Describe the research procedures, and explain if your procedures differed from Thelen’s procedures. Summarize the results of your study. Discuss how your results compare with those of Thelen, Fisher, and Ridley-Johnson. Discuss any discrepancies.

Source: Thelen, E., Fisher, D. M., & Ridley-Johnson, R. (1984). The relationship between physical growth and a newborn reflex. Infant Behavior and Development, 7, 479–493.

23