Coherence and Corporeality: On Gaius II,12-14

Von Francesco Giglio

1. Introduction

“So far we have considered the law of persons; now, we shall move to the things, which either can be in our patrimony or can be had outside our patrimony”1. Within the law of things, the summa divisio is between the things of divine law and those of human law2, which are grouped into private and public3. Private things are mostly in the patrimony of private individuals – alicuius in bonis4. In this context, Gaius asserts in the second book of his Institutes that private things are either corporeal or incorporeal5. This laconic statement has sparked ardent discussions amongst Romanists and private lawyers alike because it has repercussions for our understanding of proprietary relationships both in Roman law and in modern legal systems6.

Gaius’s text and the reason for so much intellectual upset are examined in the first part of this paper. The cultural origins of the classification of corporeal and incorporeal things are introduced in the second part, with the aim of locating it on the map of the intellectual movements of its time. The third part is dedicated to the legal analysis of the Gaian passage. The investigation of the theoretical accounts of Gaius’s scheme will provide the framework for a theory which acknowledges the perspective of the German Pandectists but departs from their conclusions. It will be argued that the Gaian taxonomy at issue is linked to a cultural development which Gaius, a member of the Sabinian school reformed by Julian, absorbs and reproduces in his own work. Furthermore, it will be maintained that the categorisation of things into those that are corporeal and those that are incorporeal was introduced by the

I am grateful to Okko Behrends, Frits Brandsma, Dmitry Dozhdev, Jan Lokin, John Murphy and Martin Schermaier for their comments on earlier drafts of this paper. I would like to acknowledge the substantial support of the Leverhulme Trust. 1 Gai. inst. 2,1. 2 Gai. inst. 2,2. 3 Gai. inst. 2,10. 4 Gai. inst. 2,9. 5 Gai. inst. 2,12: Quaedam ... res corporales sunt, quaedam incorporales. 6 For a comparative perspective, see G.L. Gretton, Ownership and its Objects, in: RabelsZ 71 (2007) 802-851. Roman jurist in the context of his academic teaching and should be read in the light of Gaius’s effort to arm his students with the necessary tools for their future profession. Against this background, it was perfectly sensible for him to link the list of legal objects to the terminology of the legal claims. This didactic approach accounts for his choice of two classes of things which are entirely consistent from this perspective.

2. The Gaian Classification

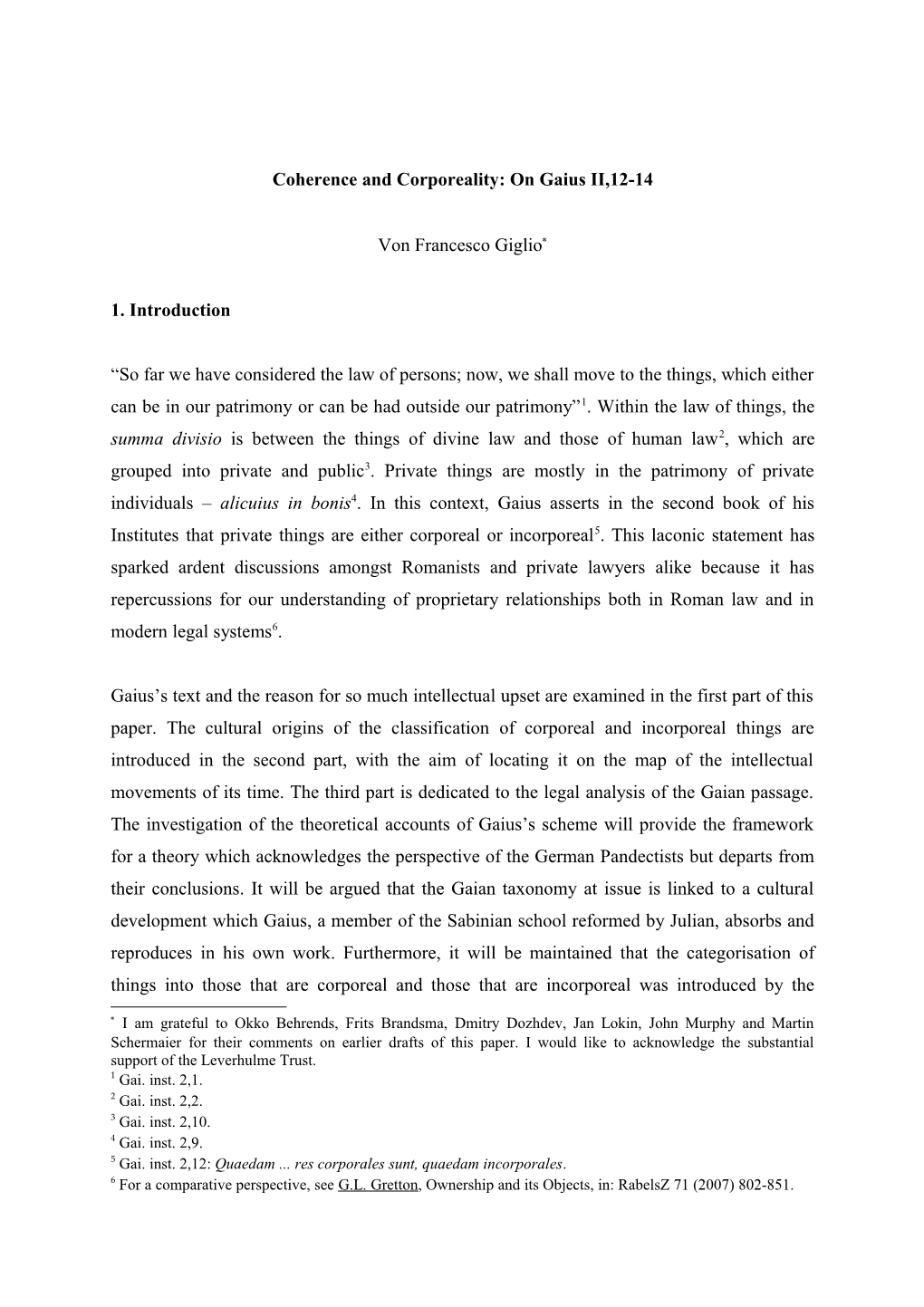

With reference to the things which can be in the patrimony of private individuals, Gaius tells us that there are two main classifications. The first one distinguishes the things according to a criterion of corporeality. The second classification concerns legal ways to convey ownership of things, which can be mancipi or nec mancipi. On the surface, the first classification seems quite straightforward. Corporeal things are “those which can be touched, such as a plot of land, a slave, clothes, gold, silver, and further innumerable other things”7. Incorporeal things, on the other hand, “cannot be touched, such as those which exist in law, as for example inheritance, usufruct, obligations in whichever manner they are brought about”8. The two lists can be displayed graphically thus:

THINGS (Gaius)

Corporeal Incorporeal (can be touched) (cannot be touched) Land Inheritance Slave Usufruct Clothes Any kind of obligations Gold Rustic / urban praedial rights Silver Countless other things

7 Gai. inst. 2,13:

This scheme presents some peculiarities that have surprised scholars. Its most striking feature is the absence of any express reference to the right of ownership. The Pandectists were not comfortable with this absence. Their uneasiness emerged clearly in Bernhard Windscheid’s words: one should not give to this classification a wider meaning than it actually had, the great German scholar observed9. In his view, in the taxonomy of things corporeal and incorporeal the word res would refer to rights. The classification would list elements of the patrimony10. However, “patrimony” is a legal concept and as such it can be formed only by rights. From what Windscheid says, it would follow that, by introducing the category of tangible objects, Gaius made a logical error, for he placed under the same roof elements with a very different, indeed incommensurable, nature. Physical things are objects of the material world. They do not pertain to the world of ideas, to which the legal concepts belong. Hence, unlike the rights over corporeal things, corporeal things, of themselves, cannot be patrimonial objects. Approaching the Gaian classification from the Pandectist perspective would lead to the inevitable conclusion that, as only rights can be elements of a patrimony, the latter is constituted solely by incorporeal things. And yet the Gaian “patrimonial” scheme contains both tangible and intangible things. Many eminent scholars have struggled with this apparent incongruence. From Friedrich Carl von Savigny11 to Heinrich Dernburg12, from Max Kaser13 to Barry Nicholas14, the literature is full of statements on the inadequacy of the categorisation at issue to portray what really happens in the legal system as regards the law of things.

9 B. Windscheid, Lehrbuch des Pandektenrechts, 18825, § 42, 101: “Man muß sich hüten, dieser Zusammenfaßung der Vermögensdinge unter dem Gesichtspunkte der Sache größere Bedeutung für das Recht zuzuschreiben, als ihr in der That zukommt”. 10 Ibid., § 42, n. 5: „In der Eintheilung der res in res corporales und incorporales bezeichnet res Rechte ... Es bezeichnet Vermögensbestandtheile. Den Gegensatz der unkörperlichen Sache bildet nicht das Eigenthumsrecht ... sondern die körperliche Sache”. 11 F.C. von Savigny, System des heutigen römischen Rechts, vol. V, 1841, 32: „der unbehülfliche, an sich ganz entbehrliche, Ausdruck res incorporalis”. 12 H. Dernburg, Pandekten, 1. Teil, 19027, § 67 after I b: „Man identifiziert dabei das Eigentumsrecht mit der Sache, da es dieselbe total umspannt. Es wird also wie etwas Körperliches aufgefaßt, obgleich es in Wahrheit wie jedes andere Recht nur in der Idee besteht”. 13 M. Kaser, Gaius und die Klassiker, in: ZRG RA 70 (1953) 127, 143: “diese logisch bedenkliche Scheidung in Sachen und Rechte”. 14 B. Nicholas, An Introduction to Roman Law, Oxford 1962, 107: “It is a convenient distinction … but on strict examination it is illogical”. 3 Any analysis which moves from the Pandectist interpretation of the Gaian taxonomy relating to tangibles and intangibles must face at least two questions: Why is there seemingly no reference to ownership? Why did Gaius not realise that tangible things, strictly speaking, cannot be regarded as patrimonial objects? These are issues which should be examined in the context of a legal-analytical investigation, such as the one conducted by the Pandectists. However, the Institutes were written as a textbook. As we might assume from the language used, they probably reflected quite closely Gaius’s lectures, which were conceived to shape the fresh minds of law students. As any law lecturer would do, particularly one with Gaius’s talent, he was not simply providing technical data to his audience. He was conveying his vision of the Roman private law system to an audience which might hopefully adopt it in their future professions. This vision included methodological, theoretical and philosophical influences. It is therefore useful to begin the examination by placing the topic under consideration in the cultural context that generated it.

3. The Cultural Sources of the Classification

Greece’s influence over Rome is evident in every sector of culture, from the arts to philosophy. The Roman jurists were learned men; it is inconceivable that they were not well acquainted with the Greek ways15. Some authors caution, with reference to the Roman pragmatism, that the jurists might have acknowledged the pre-eminence of Greek culture without at the same time founding their analysis upon Greek philosophy. Thus, Alberto Burdese maintains that Roman law incorporated cultural inputs only in so far as such incorporation was convenient to achieve given aims16. There seems to be, therefore, some recognition among the Romanists that Greek philosophy was likely to play a certain role in Roman legal thinking, although the nature of this role is disputed17. As regards the topic at

15 See the proceedings of the Italo-French Colloquium “La filosofia greca e il diritto romano”, Rome 1976. The theory of a link between Greek philosophy and Roman legal workmanship has been advanced, among others, by H. Göppert, Einheitliche, zusammengesetzte und gesammt-Sachen nach römischem Recht, Halle 1871 and P. Sokolowski, Die Philosophie im Privatrecht, vol. I: Sachbegriff und Körper, 1907. More recently, F. Wieacker was one of the firsts to acknowledge a Greek influence on Roman law, to the analysis of which he dedicated two paragraphs of his Römische Rechtsgeschichte, vol. I, 1988, §§ 38 and 39. Mario Bretone has also provided important contributions to the debate; see M. Bretone, I fondamenti del diritto romano – Le cose e la natura, 2001. This topic has been examined in several works by O. Behrends, e.g. Institutionelles und prinzipielles Denken im römischen Recht, ZRG RA 95 (1978) 187-231, now published in M. Avenarius/R. Meyer-Pritzl/C. Möller (eds), Institut und Prinzip, 2004, 15-50, 41-49. 16 A. Burdese, ‘Res incorporalis’ quale fondamento culturale del diritto romano, in: Labeo 45 (1999) 98-110, 108. 17 Wieacker (n. Error: Reference source not found), 618 observes: “Bei der unbedingten Herrschaft griechischer Philosophie und Paideia über alle Theorie in Rom ist die Frage nach der Wissenschaftlichkeit der spätrepublikanischen Jurisprudenz nicht zu trennen vom Einfluß der Anweisungen der nachsokratischen ‘Dialektik’ auf die Bildung von Begriffen und allgemeinen Sätzen und auf den systematischen Aufbau von 4 issue, there is wide agreement on the absence of pre-Gaian legal sources that expressly refer to both tangibles and intangibles as part of the same framework. It is also generally acknowledged that corporeality was an important concept of the philosophical movements which preceded Gaius’s Institutes. These two issues have generated a debate which centres upon the creative vein of Gaius as a jurist – that is, whether Gaius was the first to translate philosophical values into legal ones – and the legal significance of the pre-Gaian, non-legal theories on corporeal and incorporeal things.

The works of the Greek and Roman philologists offer a convenient starting point to investigate the cultural roots of the Gaian classification. The grammatici were already acquainted with the distinction between corporeal and incorporeal objects long before Gaius incorporated it into his legal theory. Thus, the grammarian Flavius Charisius writes an Ars Grammatica around two centuries after Gaius. In that work, which is a compilation of much older texts, there are references to the criteria of “visibility and tangibility” 18. This might indicate that the jurists, and in particular Gaius, imported into law categories which they had encountered during their general studies19. However, it is doubted in the literature whether Charisius’s work can be taken as an example of cross-fertilisation20. The grammarian’s list of objects, it is noted, does not share any common element with the jurist’s list21. Mario Bretone adds that any speculation on a link between Charisius’s and Gaius’s classifications, similar as they might be, is redundant, for Charisius followed the grammarian tradition and therefore did not need Gaius22. Yet, although the role of Charisius as a testimony of a connection between non-legal sources and legal classifications is questioned, his texts confirm at least that the categorisation of objects on the basis of the criterion of corporeality was not a concept newly fashioned by Gaius but is likely to belong to a older cultural tradition of which the Roman jurist was possibly aware.

Einzelwissenschaften”. Recently, the arguments in favour and against such influence have been weighed in the academic dispute between Okko Behrends and Dieter Nörr. See D. Nörr, Exempla nihil per se valent, in: ZRG 126 (2009) 1-54, 44-50 and O. Behrends, Wie haben wir uns die römischen Juristen vorzustellen? Ein Frage aus Anlaß einer Kontroverse erörtert, in: ZRG RA 128 (2011) 83-129. 18 Char. gramm. (ed. Barwick); see for instance XI de obseruationibus nominum quibus genera et numeri discernuntur, p. 39: item singularia semper sunt quae nec uideri nec tangi possunt, uerum ab his in alterutram partem doloris aut gaudii adficimur, ut gaudium χαρά. 19 For Kaser (n. Error: Reference source not found), 142, the classification is a direct derivation from the grammarian works. 20 See W. Dajczak, Der Ursprung der Wendung res incorporalis im römischen Recht, in: RIDA 50 (2003) 97- 117, 100. 21 Cf. Bretone (n. Error: Reference source not found), 171-173. 22 Ibid., 172: “Carisio seguiva la tradizione dei suoi studi, e non aveva alcun bisogno di Gaio (lo conoscesse o no)”. 5 Cicero’s work offers more solid arguments to posit a connection between legal and non-legal analysis. The structure and the formulation of the distinction between what can be and what cannot be touched in the analyses of Charisius and Cicero elicits the question whether the respective classifications are too close to be merely coincidental. Let us consider the grammarian’s first23:

the appellations … are divided in two species, of which one identifies corporeal things, which can be seen and touched, such as human beings, earth, and sea; and the other incorporeal things, such as piety, justice, and dignity, which can be perceived only through the intellect, and indeed cannot be seen or touched.

What is of particular interest in the present context is the fashion in which the grammarian distinguishes all things: they either can be seen and touched or can be perceived. Charisius qualifies the partition with examples that have no immediate relation to law. Even the use of a term such as “justice”, far from conferring any legal relevance to the scheme, in this context points out that Charisius was simply looking for clear illustrations which would be understandable to his, non-legal, audience. Here is a graphic representation of his taxonomy:

THINGS (Charisius)

Corporeal Incorporeal (can be seen and touched) (cannot be seen or touched) (perceived through intellect) Man Piety Earth Justice Sea Dignity

Charisius’s classification can be usefully compared with a well-known passage of the Topica, in which Cicero distinguishes things which “are” from things which can “be comprehended”24. The former can be perceived and touched, whereas the latter cannot be touched or demonstrated (tangi demonstrarive) but can be perceived with the intellect (cerni

23 Char. gramm. (ed. Barwick) p. 193-194: appellatiua autem … in duas species diuiduntur, quarum altera significat res corporales, quae uideri tangique possunt, ut est homo terra mare, altera incorporales, ut est pietas iustitia dignitas, quae intellectu tantum modo percipiuntur, uerum neque uideri nec tangi possunt. 24 Cic. top. 26-27: Definitionum autem duo genera prima: unum earum rerum quae sunt, alterum earum quae intelleguntur. Esse ea dico quae cerni tangique possunt, ut fundum aedes, parietem stillicidium, mancipium pecudem, supellectilem penus et cetera; quo ex genere quaedam interdum vobis definienda sunt. Non esse rursus ea dico quae tangi demonstrarive non possunt, cerni tamen animo atque intellegi possunt, ut si usus capionem, si tutelam, si gentem, si agnationem definias, quarum rerum nullum subest corpus, est tamen quaedam conformatio insignita et impressa intellegentia, quam notionem voco. 6 animo atque intellegi). So far, the parallels with Charisius are remarkable. Yet, unlike Charisius’s, Cicero’s classification seems to take “existence” as the decisive criterion to distinguish the categories: only corporeal things “are”. Unsurprisingly, given the different audiences and cultural backgrounds of the authors, Cicero supports his description of both sides of the classification with examples taken from the legal terminology, such as usucapion and tutela. This use of legal terms can hardly be a matter of chance, given that Cicero had developed a familiarity with legal matters through his contacts with the Mucii25. Yet, claims that the Roman orator was deliberately seeking to provide a theoretical framework for both philosophical and legal reflections have so far been unable to convince the majority of the Romanists26. Rather, it is pointed out that there are clear differences between Cicero’s and Gaius’s taxonomy. In the literature, Cicero’s qualification of the incorporeal things as merely intellectually comprehensible res is interpreted by some authors as a signal that the distinction was not devised to help the organisation of legal reasoning27. These are Cicero’s lists:

THINGS (Cicero)

Corporeal Incorporeal (are) (can be comprehended) (can be distinguished and touched) (can be distinguished and perceived with intellect) (have no body) Land Usucapion Temples Guardianship Walls Gens Dropping moisture Male consanguinity Slave Sheep Furniture Food

25 Cic. Lael. 1: ego autem a patre ita eram deductus ad Scaevolam sumpta virili toga, ut, quoad possem et liceret, a senis latere numquam discederem; itaque multa ab eo prudenter disputata, multa etiam breviter et commode dicta memoriae mandabam fierique studebam eius prudentia doctior. Quo mortuo me ad pontificem Scaevolam contuli. 26 The stronger supporter of such claims being, in modern times, Okko Behrends. 27 R. Monier, La date d’apparition du dominium et la distinction juridique des res en corporales et incorporales, in: Studi in onore di Siro Solazzi, Napoli 1948, 357-374, 361. 7 Note the terminology adopted in the three classifications examined so far with regard to the human being. Charisius uses the same expression, homo, as Gaius. But for Charisius, and unlike Gaius, homo is a general term which embraces all creatures, without distinguishing their social and legal status. On the other hand, Cicero and Gaius, albeit employing different words, mancipium and homo respectively, refer to the same concept, that is the slave. Gaius was aware that slavery was a legal status contra naturam, not a natural human condition. A homo can be classified as a thing only from the perspective of law28.

At first sight, it is Seneca’s position which reveals more points of contact with Gaius’s scheme than Cicero’s view. The stoic philosopher states that “what is” (quod est) can be corporeal or incorporeal29. Hence, Seneca refers expressly to the category of intangible things – introducing a classification which can be directly translated into legal categories. Moreover, he accepts that even intangibles exist. Seneca acknowledges that the previous generations of Stoics had not used the distinction which he proposes. They had differentiated between “things that are” (quaedam sunt) and “things that are not” (quaedam non sunt)30. For Wojciech Dajczak, the difference introduced by Seneca might have influenced Gaius. Dajczak formulates the hypothesis that Seneca’s ontological vision would support Gaius’s categories. Gaius was introducing a classification of things that are in the patrimony – things that “are” – and Seneca was classifying “what is”. Hence, Seneca would offer a valuable working model to Gaius31. Indeed, Seneca might have been the first to use the term “incorporeal”, which Cicero had not employed, in a philosophical context as an “existing” element – as opposed to simple “void”32. Despite the ontological differences between Cicero and Seneca, the case is made in the literature that the works of both these authors might have influenced Gaius. Seneca provided clear contours to the distinction33, whereas Cicero’s legal examples might come more or less directly from the works of Quintus Mucius34.

28 Cf. Florentinus D. 1,5,4,1: Servitus est constitutio iuris gentium, qua quis dominio alieno contra naturam subicitur. See also Ulpianus D. 1,1,4,1: cum iure naturali omnes liberi nascerentur nec esset nota manumissio, cum servitus esset incognita. 29 Sen. epist. 58,14: ‘Quod est’ in has species divido, ut sint corporalia aut incorporalia; nihil tertium est. 30 Ibid., 15: Primum genus Stoicis quibusdam videtur 'quid'; quare videatur subiciam. 'In rerum' inquiunt 'natura ... quaedam sunt, quaedam non sunt, et haec autem quae non sunt rerum natura complectitur‘. 31 Dajczak (n. Error: Reference source not found), 102-103. 32 R.W. Sharple, Stoics Epicureans and Sceptics, London 1996, 47: “What is incorporeal ‘subsist’ … but does not exist” (with reference to stoic philosophy). 33 Monier (n. Error: Reference source not found), 361. 34 Bretone (n. Error: Reference source not found), 181. 8 4. Gaius’s Classification between Stoicism and Scepticism

Many Romanists locate the origin of the Gaian classification at issue in stoic philosophy. Cicero’s relationship with the Mucii is well documented. The Mucii were followers of the stoic doctrines. Seneca was a stoic philosopher. However, the interest of the Republican jurists for the stoic movement does not necessarily indicate that Cicero too applied stoic philosophy whilst distinguishing things according to a criterion of corporeality or lack thereof.

In fact, Cicero clarifies in the Partitiones oratoriae that he follows the precepts of the Sceptic Academy (e illa nostra Academia)35. The few voices raised against the “near to unanimous assumption that Cicero was an unswerving adherent of the sceptical Academy throughout his life” are convincingly counteracted by Woldemar Görler36. For the German author, Cicero does wish to believe in dogmatic tenets, such as the immortality of the soul and the self- sufficiency of virtue, but is restricted from embracing them by his recognition “that none of this could ever be proved”37.

In his exposition of the theory of definition in the Topica, Cicero refers to two orders of classification. The first group comprises the things corporeal and incorporeal. In the second group, the author distinguishes partition (partitio), that is division in parts, from division (divisio), that is division in species38. Following Görler’s analysis, we have to conclude that both classifications should be considered in the context of Cicero’s sceptic persuasion.

In this context, it should be noted that Cicero and Servius shared a passion for sceptic philosophy and went to the lectures delivered by Philo of Larissa39 during his Roman sojourn. 35 Cic. part. 139. 36 W. Görler, Silencing the Troublemaker, in: C. Catrein (ed.), Kleine Schriften zur hellenistisch-römischen Philosophie von Woldemar Görler, Leiden/Boston 2004, 240-267, 240 (first published in 1995). 37 Ibid. 265. 38 Cic. top. 28: Atque etiam definitiones aliae sunt partitionum aliae divisionum; partitionum, cum res ea quae proposita est quasi in membra discerpitur, ut si quis ius civile dicat id esse quod in legibus, senatus consultis, rebus iudicatis, iuris peritorum auctoritate, edictis magistratuum, more, aequitate consistat. Divisionum autem definitio formas omnis complectitur quae sub eo genere sunt quod definitur hoc modo: Abalienatio est eius rei quae mancipi est aut traditio alteri nexu aut in iure cessio inter quos ea iure civili fieri possunt. – Cicero tells us also that the two categories require different procedures: a division in parts would not be incorrect if it failed to list all parts when it concerned a res infinita. On the other hand, a division in species ought to enumerate all the species included in the classification: At si stipulationum aut iudiciorum formulas partiare, non est vitiosum in re infinita praetermittere aliquid. Quod idem in divisione vitiosum est. Formarum enim certus est numerus quae cuique generi subiciantur; partium distributio saepe est infinitior, tamquam rivorum a fonte diductio, top. 33. 39 Cic. Brutus 306: eodemque tempore, cum princeps Academiae Philo cum Atheniensium optumatibus Mithridatico bello domo profugisset Romamque venisset, totum ei me tradidi admirabili quodam ad 9 Okko Behrends argues that the sceptic tenets influenced Gaius as well: whilst Cicero was interested in the theory of definition (“Definitionslehre”), Gaius worked on the theory of patrimony (“Vermögenslehre”)40. Yet, their theories adopted the same scheme: the objects are tangible or not and in either case the classification is embedded within the sceptical theory of knowledge. Cosima Möller’s study on the Roman servitudes has recently provided further support to the claim that stoicism did not provide the philosophical matrix for Cicero’s classification41.

Behrends’s conjecture offers a coherent account of the Gaian scheme. Gaius is categorising those elements of the factual, or material, world which are relevant to the law because they can be the objects of patrimonial rights. At the same time, Gaius considers also the patrimonial rights themselves, which are beyond the material world and originate in the world of the law. Behrends refers to a fundamental dichotomy between natura and institutio, that is, what belongs to nature and what is created by our intellect. The former has factual character. It exists because it is there and can be touched. The latter has normative character. It exists because it is created rationally. The “nature and institution” dichotomy, for Behrends, was a classical distinction still kept by Ulpian in his Institutes. It might therefore represent the mainstream view during Gaius’s time. But Gaius, coherently with his academic allegiance, prefers to follow Julian’s approach and bases his system upon the two pillars of ius gentium and ius civile42, coalescing nature and law in the name of a naturalis ratio, which is the system of rules shared by all peoples, as opposed to the special rules that characterise the legal system, the ius civile43. Behrends’s explanation supplies a persuasive theory of the relationship which links natural and legal objects. It offers an answer to the question, which philosophiam studio concitatus.. I am grateful to Okko Behrends for a yet unpublished manuscript in which he delineates the development of the dialectic method used by the Sceptics: Philo of Larissa’s work in this area is linked to Plato’s Theaetetus, in which the great Greek philosopher distinguishes tangibles from intangibles and introduces the distinction between partition and division which can be found in Cicero, cf. O. Behrends, Die geistige Mitte des römischen Rechts, ZRG RA 125 (2008) 25-107, 44-54. – On Philo, see C. Brittain, Philo of Larissa: The Last of the Academic Sceptics, Oxford 2001. The title of the monograph clarifies the author’s position: Philo might have taken a peculiar philosophical stance in the last, Roman, phase of his life. But, for Brittain, Philo’s philosophical innovations, contained in the lost Roman Books, were still in line with the evolutionary pattern of the Sceptic Academia. His pupil Antiochus of Ascalon, who was one of Cicero’s teachers too, abandoned sceptic analysis in favour of a more dogmatic approach. Cicero presents Antiochus’s view in the Academici libri, in which Varro follows Antiochean tenets. W. Görler, Antiochos von Askalon über die ‘Alten’ und über die Stoa, in: Catrein (n. Error: Reference source not found, but article first published in 1990) 87-104, argues convincingly that Cicero, in the missing part of the libri, would embrace the sceptical position – probably following Philo: “Ohne Frage wird er [sc Cicero] denn auch am Ende des uns leider verlorenen Dialogs als der ‘Sieger’ dagestanden haben”, Görler 89. 40 O. Behrends, Die Person oder die Sache?, Labeo 44 (1998) 26-60, 39-40. 41 C. Möller, Die Servituten, Göttingen 2010, 222-228. 42 Behrends, Labeo 44 (1998) 38. 43 Gai. inst. 1,1. 10 has puzzled many generations of scholars, of the absence in pre-Gaian authors of references to a classification similar or leading to the one later adopted by Gaius. The Roman jurist, according to this interpretation, opted for a view that departed from the more traditional accounts. The latter stuck to the natura and institutio division. Hence, Gaius followed a path which might not have been accepted by most of his contemporaries and by subsequent generations of jurists.

Möller’s analysis helps to understand the difference between Gaius and the authors who did not distinguish corporeal from incorporeal things: the dualism of Servian origin contained in the couplet natura and institutio was embraced by Gaius, a Sabinian, after the new course steered by Julian, who incorporated elements of the institutional reasoning typical of the Proculians into Sabinian reasoning44. Following the avenue opened by the head of the Sabinian School, Gaius used the dualistic approach – considered from the novel perspective of the naturalis ratio – as the basis of his distinction of things corporeal and incorporeal. The left-hand list would be dedicated to natura, which explains the materiality of the objects enumerated. The right-hand list would contain things posited – instituted – by the human mind. One is tempted to conclude that the lack of sources might indicate a general rejection of the theory behind Gaius’s taxonomy. However, although this possibility cannot be excluded, it appears quite improbable given the weighty influence of Julian’s doctrines upon Gaius’s work.

As will be argued later on, Gaius created the classification at issue with a specific, didactic goal in mind: he used it to point up in his lectures the connections between the law of things and the law of actions. Yet, the traditional stoic tenets could not provide theoretical support to his classification of res corporales and incorporales, as Seneca’s analysis of things corporeal and incorporeal reveals.

The philosopher argues that quod est can be tangible or intangible. It follows that, for Seneca, even incorporeal objects “are”. However, Seneca himself tells us that this was not what the Stoics before him thought. The earlier generations distinguished between “what is” and “what is not”, the latter having no substance45. Hence, for the Stoics, anything which had no

44 Möller (n. Error: Reference source not found) 227-228. 45 Sen. epist. 58,15: Primum genus Stoicis quibusdam videtur 'quid'; quare videatur subiciam. 'In rerum' inquiunt 'natura quaedam sunt, quaedam non sunt, et haec autem quae non sunt rerum natura complectitur, quae animo succurrunt, tamquam Centauri, Gigantes et quidquid aliud falsa cogitatione formatum habere aliquam imaginem coepit, quamvis non habeat substantiam. 11 substance – an incorporeal thing – was not. The stoic alternative to corporeality was “void”. It is well-known that stoic philosophy saw nature as the produce of divine creation. The latter includes everything, even the legal principles which become concrete – almost corporeal – in the reality surrounding the human being46.

If this analysis is correct, Cicero’s classification based upon sceptic precepts supplied the best theoretical framework to Gaius. Stoic philosophy was unable to provide a support to the scheme in question because of the fashion in which the Stoics considered incorporeal things. Indeed, Seneca’s classification was not in line with the traditional stoic tradition. It is quite possible that the Roman philosopher in the relevant passage of the epistulae appropriated sceptic tenets, which leads us back to the Sceptics.

The difference in the theoretical approach adopted by the Roman jurists does matter. It is central to comprehending how the Republican, the pre-classical, and then the classical lawyers saw the incorporeal things. A good starting point to highlight the practical importance of this issue is offered by the famous case of Theseus’s ship47:

The ship on which Theseus sailed with the youths and returned in safety, the thirty-oared galley, was preserved by the Athenians down to the time of Demetrius Phalereus. They took away the old timbers from time to time, and put new and sound ones in their places, so that the vessel became a standing illustration for the philosophers in the mooted question of growth, some declaring that it remained the same, others that it was not the same vessel.

The issue concerned the identity of the ship: can an object whose components have been integrally dismantled and then reassembled be regarded as identical to the original object prior to the substitutions? The Stoics and the Sceptics worked out opposite answers to this question. The concept of universitas, the association of citizens, contributes to the clarification of the link between Theseus’s ship and the taxonomy of things corporeal and incorporeal. To qualify a universitas as a body different from its members, one must accept that the institution universitas survives the departure of its members48. In other words, the idea of universitas as a body which is independent of its components is only possible if it is seen as an abstract concept, a res incorporalis49. The concept of incorporeal thing allows the continuity before and after the destruction of the ship because its – intangible – identity is not affected by the

46 Möller (n. Error: Reference source not found) 225. 47 Plut. Thes. 23,1 (transl. by B. Perrin, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University, repr. 1998). See O. Behrends, Das Schiff des Theseus und die skeptische Sprachtheorie, Index 37 (2009) 397-452, part. 422-442. 48 See Behrends, ZRG RA 125 (2008) 47-50. 49 Gai. inst. 2,14, states about the inheritance as an incorporeal thing that ‘it is immaterial that tangibles are comprised in the inheritance’. 12 change. Sceptic philosophers, who acknowledged the concept of incorporeal thing, would accept the idea that the disassembled ship could be put back together without losing its identity. If, on the other hand, universitas is identified with its members, that is each one of them, then it is regarded as a corpus ex corporibus and the separation of its elements changes the nature, the essence, of the association, which, consequently, cannot be abstractly conceived. According to the first interpretation, a universitas can even be composed by only one member. According to the second, stoic, interpretation, there can be no such legal structure.

The very same idea is discussed in the legal sources, which confirms that this issue does not concern a purely speculative question. Thus, if a building is completely demolished to be re- built in an identical fashion, does a servitude over the old building survive in the new edifice? The survival in the new building of the old charge requires an ideal continuity between old and new structure which presupposes that the identity of the thing has not been compromised by the material demolition of the structure50. Once again, only the – sceptic – concept of incorporeal thing supports this construction.

As intimated, Cicero’s theory of definition contains only two schemata: the classification of things corporeal and incorporeal and the distinction between division in parts, or partitio, and division in species, or divisio. “Partition” implies the possibility of breaking a unity into pieces, such as the different parts of a statute or of the magistrate’s edict – or, one might add, the members of a universitas. In the case of a “division”, there is nothing that can be broken in smaller parts. Rather, a division orders concepts into a genus-to-species relationship. A well-known controversy between Quintus Mucius and Servius Sulpicius Rufus reported by Paul in his work on the Edict provides an excellent example of the interaction of the two schemata of definitions. It concerns a dispute on the concept of ownership. The passage opens with Paul’s statement that it is not wrong to assert that the whole thing (totum) is somebody’s if none of its parts can be said to be of another person51. Discussing this view, which was

50 Paul. 15 ad Sab. D. 8,2,20,2, justifies the transfer of the servitude from the old to the new building on the basis of utilitas: Si sublatum sit aedificium, ex quo stillicidium cadit, ut eadem specie et qualitate reponatur, utilitas exigit, ut idem intellegatur: nam alioquin si quid strictius interpretetur, aliud est quod sequenti loco ponitur: et ideo sublato aedificio usus fructus interit, quamvis area pars est aedificii. 51 Paul. 21 ad ed. D. 50,16,25 pr: Recte dicimus eum fundum totum nostrum esse, etiam cum usus fructus alienus est, quia usus fructus non dominii pars, sed servitutis sit, ut via et iter: nec falso dici totum meum esse, cuius non potest ulla pars dici alterius esse. Hoc et Iulianus, et est verius. 13 shared by Julian, Paul reports the respective positions of Quintus Mucius and Servius Sulpicius as regards the concept of ‘part’ in the context of ownership52.

Mucius accepts only the possibility of undivided ownership. In his view, several persons can share ownership – can have a part – of the same thing only if each title-holder has a right to the whole (pro indiviso). By contrast, for Servius a “part” of ownership can relate to a general right shared by all title-holders pro indiviso, as Quintus Mucius argues, but also to a specific right of each individual owner to a discrete part of the whole (pro diviso). Bretone tentatively explains this passage as a disagreement concerning theoretical notions or mental representations (“nozioni o rappresentazioni mentali”)53. “Part”, in this context, would be regarded as an incorporeal thing by both Quintus Mucius and Servius Sulpicius who held opposite views as regards its meaning. It seems, however, that this passage can be explained in the light of an interaction of the two groups of Cicero’s theory of definition.

The concept of “part” refers to the diairetic, as opposed to the tangibility-based, method presented by Cicero in the Topica – a classification that was familiar both to the Stoics and the Sceptics54. The Stoics used it to distinguish the various branches of philosophy. Whilst discussing the right of ownership, Quintus Mucius examines this right as a whole, the ὅλος, which cannot be broken into parts without compromising its wholeness55. Hence, ownership is regarded by him as an indivisible right that could be shared, but only in its totality. The creation of parts breaks the totality and creates two or more wholes. Unlike Quintus Mucius, Servius Sulpicius can recur to the sceptic tenets, according to which intangibles “are”. The concept of res incorporalis allows him to use the Ciceronian diairetic analysis to develop a classification of ownership containing a category which enables the identification and separation of “part” of the right of ownership without endangering the identity of the right itself. Not only the pars pro indiviso, therefore, but also the pars pro diviso is in his view compatible with the notion of ownership.

52 Paul. D. 50,16,25,1: Quintus mucius ait partis appellatione rem pro indiviso significari: nam quod pro diviso nostrum sit, id non partem, sed totum esse. servius non ineleganter partis appellatione utrumque significari. 53 Bretone (n. Error: Reference source not found) 187. 54 D. Nörr. Divisio und Partitio, Berlin 1972, 20-27; K. Ierodiakonou, The Stoic Division of Philosophy, in: Phronesis 38 (1993) 57-74, 62-67. 55 Ierodiakonou, Phronesis 38 (1993) 62-63 (examining the Stoic account of μέρος, which can be translated as pars): “according to our sources (cf. PH III 98), if a part ceased to exist, the whole is also said to be destroyed; on the other hand, the standard view in Greek philosophy (cf. Aristotle, Met. 1059b34-40), which we may reasonably suppose was shared by the Stoics, is that the genus does not perish, if one of its species becomes extinct”. 14 The aim of the two jurists in the debate at issue was to set the boundaries between sole ownership and co-ownership. The theory of definition reported by Cicero, which encapsulated the diairetic and the tangibility-based method, offered a support for the exposition of their different visions reflecting different philosophical perspectives, which in this case were linked to the concept of res incorporalis.

5. The Legal Origin of the Classification

It seems, therefore, that there was plenty of material from which Gaius could draw inspiration for his division. The scheme marks an essential passage of the Gaian Institutes because it provides a crucial element of his normative theory of law. Gold, clothes, and land, from this perspective, partake of the same normative values as usufructs and servitudes. Such a result, of itself, would already justify the importance which this taxonomy has enjoyed through the centuries until present times. An explanation in terms of its normative value, however, does not deal with the role of the Gaian scheme within the system of legal rules of the Institutes from an analytical perspective. The examination of this role will be the next step of this investigation. Yet before locating the legal function of the classification on Gaius’s map of private law, it is opportune to spend a few words on the question of its legal origin.

It is a matter of debate who introduced the “Gaian” classification, although it is commonly accepted that Gaius was the first jurist to adopt it56. Kaser observes that, in the sources, the few passages where it is mentioned are all by late classical jurists57. Raymond Monier accepts that Gaius was the first one to adopt the scheme but does not credit the Roman lawyer with having developed it. Gaius would not present the degree of originality which is necessary to achieve such a task58. Bretone finds a compromise between these two views by observing that, systematically, the distinction is Gaian, but the legal concept of intangible thing was much older, probably going back to Quintus Mucius Scaevola59.

56 V. Arangio-Ruiz, Istituzioni di diritto romano, Napoli 196014, 162-163, was probably the first scholar to advance this view. 57 Kaser (n. Error: Reference source not found), 143. 58 Monier (n. Error: Reference source not found), 363. 59 Bretone (n. Error: Reference source not found), 189. This explanation has been confuted under the previous heading. 15 The concept of corporeality was used by the jurists even before Gaius, but in a different context60. If, like Behrends, one accepts that Gaius founded his private law system upon a newly interpreted concept, the naturalis ratio, the view which ascribes the work to him or his pupils seems the most plausible: the classification of res corporeal and incorporeal can be explained in philosophical terms in the light of the Gaian understanding of the dichotomy ius civile and ius gentium. Gaius was a classical jurist, whereas Ulpian was a late classical author. But, as intimated, Ulpian based his jurisprudence upon a normative account which used the schema natura/institutio, whereas Gaius preferred the concept of naturalis ratio. Hence, Gaius follows an avenue which might not have been acknowledged as orthodoxy – the latter being represented possibly by Ulpian. The fact that in the sources there are very few references to this aspect of his work seems to suggest that, on this issue, Gaius supported original ideas. Even if it is accepted that Gaius might not have been a legal innovator, still he espoused an innovative theory with major reflections upon his legal taxonomy.

It is possible that the historical events taking place in the few decades which separate Gaius from Ulpian might help to explain why the two authors opt for different methods in their respective Institutes. Gaius looked at Cicero rather than Seneca although the time-span which separated Cicero from Gaius was much wider than that between Gaius and Seneca. It may seem odd that Gaius went back to Cicero’s age to find inspiration for his classification while there were helpful theories closer to him, given that Seneca was born more than forty years after Cicero’s death. Yet, this kind of approach is in line with the method adopted by Gaius. As the frequent references to the Twelve Tables in the Institutes testify61, the Roman jurist tended to link his jurisprudence to the elder tradition, particularly the oldest sources. From this perspective, Cicero the Republican and consul might have offered a more authoritative model than the stoic Seneca, who was active in the Principate. The late classical jurists abandoned this backward-looking approach, to concentrate on the more pressing tasks emerging under the Severi.

There is final issue that needs to be briefly considered. Gaius was a Sabinian. If it is true that this school took over the stoic-related, principle-based reasoning of the Republican jurists, one would expect Gaius to follow stoic precepts rather than Cicero’s analysis, which was

60 See G. Pugliese, ‘Res corporales’, ‘res incorporales’ e il problema del diritto soggettivo, in: Studi in Onore di Vincenzo Arangio-Ruiz, Napoli 1953, 223-260, 245-247. 61 In the Second Book of the Institutes, the Twelve Tables are mentioned six times: 42, 45, 47, 49, 54, and 64. 16 linked to Servius’s “institutional” reasoning62. Cicero’s great respect for Servius’s legal expertise was probably a consequence of the time spent together learning sceptic philosophy. Indeed, Cicero considered Servius the “second best” orator, but the first jurist63. Hence, Servius would not appear the more straightforward choice for Gaius, who followed a different theoretical approach. However, there are several reasons which militate in favour of Servius. We have already seen that stoic theory did not provide a workable doctrine of res incorporales to Gaius. Further, Gaius wrote after the methodological changes introduced by Julian, whose conciliatory approach triggered a partial convergence of the Sabinian principle- based method with the Proculian institutional reasoning64. Additionally, cultural influences are at times overridden by more pragmatic approaches dictated by contingency reasons. For Behrends, one of these reasons is to be seen in the developments following the Res publica restituta65. The shift of the axis of power from the republican structures to the princeps transformed the status of the Romans from citizens to subjects. This change of status had a serious impact upon two of the most precious rights. Ownership and freedom were no longer considered as essential components of the legal status of the Roman citizens. Rather, they were granted to the subjects by a superior authority. Gaius’s analysis, in which ownership was regarded as a concept linked to the power of the princeps, rather than as a legal institution, would reflect for Behrends the changes in the cultural climate.

6. The Meaning of the Classification

Commenting on the Gaian scheme, Hans Kreller argues that Gaius caused an age-old confusion (“säkulare Verwirrung”) because he compared tangible things with positions of dominion having legal content (“Machtpositionen rechtlichen Inhalts”). The two categories would concern incommensurable measures and were therefore inadequate as a basis for a

62 For an analysis of institutional and principle-based legal reasoning towards the end of the Republic see Behrends (n. Error: Reference source not found). 63 Cic. Brut. 151: Et ego: de me, inquam, dicere nihil est necesse; de Servio autem et tu probe dicis et ego dicam quod sentio. non enim facile quem dixerim plus studi quam illum et ad dicendum et ad omnes bonarum rerum disciplinas adhibuisse. nam et in isdem exercitationibus ineunte aetate fuimus et postea una Rhodum ille etiam profectus est, quo melior esset et doctior; et inde ut rediit, videtur mihi in secunda arte primus esse maluisse quam in prima secundus. atque haud scio an par principibus esse potuisset; sed fortasse maluit, id quod est adeptus, longe omnium non eiusdem modo aetatis sed eorum etiam qui fuissent in iure civili esse princeps. 64 This is a reductive statement. Julian’s work was the result of an exceptionally sharp legal mind, as the redaction of the Edict, entrusted to him by Hadrian, clearly shows. The analysis of the concepts of natura and institutio and of the novel idea of naturalis ratio, which have been briefly considered above, cannot be further developed here. For a more detailed analysis, see the literature cited at n. Error: Reference source not found42 and Error: Reference source not found44. 65 This theory is object of Behrends’ unpublished paper mentioned above (n. Error: Reference source not found39). 17 classification, as, in Kreller’s view, Windscheid and the Pandectists would correctly point out66. For Kaser, this classification is not only logically questionable, but also useless, because it did not have any practical impact67. In fact, the main raison d’être of the categorisation seems to be the prohibition to transfer res incorporales through simple delivery68. It is a modest task for one of the only two general classifications of the law of private things which can be in patrimonio. Still, Gaius must have considered this scheme as bearing a major significance; otherwise he would not have given it such a prominent position.

To the many detractors of the Gaian scheme one could reply with Heinrich Pflüger that an offence against logic is one of the most unlikely objections that can be put to the Romans 69. It is extremely improbable that a methodical, highly-talented jurist like Gaius did not see that he was comparing incommensurables and that, independently of the intrinsic inconsistency of the categories, he was introducing a classification with a minimal legal impact. Authors such as Behrends, Bretone, and Dajczak have sought to clarify the theoretical significance of the Gaian schema. Yet, it is the question of its legal-analytical relevance that has been predominantly discussed in the literature.

The key to understand the Gaian taxonomy on corporeal and incorporeal things is often seen in the role purportedly played by the right of ownership. Since the Pandectists, the classification has been mostly considered to be strictly entangled with patrimonial rights. “Ownership” and “patrimony” are therefore the recurring themes of most interpretations. Ownership would be an essential element despite not having been explicitly mentioned because otherwise Gaius’s silence on this right would not be explicable, given that he could not simply have forgotten it. The patrimony is seen as the other central pillar of the construction because Gaius discusses the classification in question within the context of the things which are in patrimonio. Under the combined influence of the concepts of ownership and patrimony, the most common reading of the Gaian scheme is in line with the view, advanced by the Pandectists, that the corporeal things would be those patrimonial elements that can be the object of ownership, whereas the incorporeal things would concern patrimonial rights bar ownership. Giuseppe Grosso’s analysis of the Gaian passage in a seminal set of lectures on the Roman law of things provides an excellent example of the approach just

66 H. Kreller, Res als Zentralbegriff des Institutionensystems, in: ZRG RA 66 (1948) 572-599, 585-586. 67 Kaser (n. Error: Reference source not found), 143: “Praktischen Wert hat der weite res-Begriff offenkundig keinen”. 68 Gai. II, 28. 69 H.H. Pflüger, Über körperliche und unkörperliche Sachen, in: ZRG RA 65 (1947) 339-343, 340. 18 described70. The only possible justification for the absence of the most important patrimonial right, that is ownership, in the Gaian classification has to be for Grosso that ownership, as a general and absolute seigniory over the res, affects the thing so deeply that the right is identified with the thing itself as regards its use and exploitation. Unlike the incorporeal things, the corporeal things would allow the owner to claim, “The thing is mine!” Rights, as intangibles, would only enable the right-holders to assert their title over the right in question, not to claim the right as their own. Grosso argues that Gaius proposes a theoretical structure that is in line with a practical approach. Yet, from a legal perspective the confusion between the right and its object would be a logical mistake because the terms of the distinction are heterogeneous and therefore incommensurable71.

Pflüger counteracts these arguments by advancing the idea that Gaius employs a metonymy72, that is, a figure of rhetorical speech which connects two objects seen as contiguous. Hence, when Gaius writes “slave”, “gold”, “silver”, “land”, and so forth, he means “right of ownership”. Giovanni Pugliese adds that the Romans were aware that the vindicator acquired dominium, that is ownership, but they thought that mentioning ownership would have been useless pedantry (“inutile pedanteria”), because the vindication concerned only the acquisition of ownership73. These authors argue that under ‘corporeal things’ one ought to understand “ownership”. This link between corporeality and ownership builds the backbone of Windscheid’s criticism of the Gaian classification. The German Pandectist observes that a common linguistic usage adopted by the legal terminology mentions, instead of the right of ownership, the thing over which the right is exerted74. Following Windscheid’s reasoning to its logical conclusion, one would have to conclude that res was in fact a concept which included only rights. Michel Villey turns this argument upside down. He argues that the res was a material thing and that, in the context of corporeality, it embodied rights or legal elements. Thus, there were no transfers of ownership rights, but only deliveries of things. This theory would explain why Gaius does not refer to ownership but to corporeal objects, which

70 G. Grosso, Corso di diritto romano: Le cose, in: Rivista di Diritto Romano (2001) 1-137, 11-15 (reprint of original lectures, Turin 1941). 71 Ibid., 13 and 15: “I due termini della distinzione sono dunque eterogenei; il concetto tecnico di cosa resta limitato nell’ambito delle cose corporali”. 72 Pflüger (n. Error: Reference source not found69), 342-343. The author derives this idea from Donellus. 73 Pugliese (n. Error: Reference source not found60), 241. 74 Windscheid (n. Error: Reference source not found), 42: “Ein sehr gewöhnlicher, im Leben entstandener, aber vom Rechte festgehaltener Sprachgebrauch nennt statt des Eigentumsrechts die Sache, an welcher es stattfindet”. T. Rüfner, Savigny und der Sachbegriff des BGB, in: S. Leible/ M. Lehmann/ H. Zech (eds), Unkörperliche Güter im Zivilrecht, Tübingen 2011, 33-48, n. 14 at 39, followed this idea back to J. Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 1789, edited by J.H. Burns/H.L.A. Hart, 1982, 211 n. 12: “[I]n common speech, in the phrase ‘the object of a man’s property’, the words ‘the object of’ are commonly left out”. 19 are the only ones to be actually conveyed75. Pugliese objects that, if Villey were right, the classification would be meaningless: if the rights contained in the res were heterogeneous in comparison with the thing itself, they could not be seen as res; if they were homogeneous, they could not be considered res incorporales76.

In Jan Willem Tellegen’s view77, the scheme becomes clear if the meaning of Gaius’s description of incorporeal things, quae iure consistunt, is properly deciphered. Things were often transferred in Roman law through in iure cessio, the judicial vindication of the buyer to which the seller did not object, so that the praetor could allocate the thing to the new owner. As regards this form of conveyance, there was a specific formula for corporeal things which allowed the buyer to claim, “The slave, the land, this gold is mine!” But the situation was more complex as regards res incorporales. For Tellegen, intangibles were things which existed merely for procedural purposes, in court, to give to the praetor the possibility to assign them to a party, and thus to transfer the title as if they were corporeal things78. The list of res incorporales was necessary to establish that intangibles could be the object of a vindicatio and therefore could be transferred. This thesis has been strongly criticised as being arbitrary or even “fanciful”79. As Alberto Burdese remarks, a reading of the Gaian scheme as suggested by Tellegen would imply that, within the same passage, Gaius would use the term ius both as place of jurisdiction, in iure, and as an object of the claim, res incorporalis – such as ius successionis and ius utendi fruendi80. Although it cannot be accepted, Tellegen’s analysis supplies some useful points for reflection, as will be seen.

As Tellegen laments, the theories which identify the left-hand list of the Gaian scheme – the one dedicated to the res corporales – with ownership have been so far unable to conjugate legal-theoretical and legal-analytical explanations to clarify why Gaius has introduced the classification. Even if it is accepted that the left-hand list refers to ownership, whereas the right-hand list refers to other legal interests, the reason for the classification remains unclear. Behrends’s account, which places the classification within the wider historical picture of the Res publica restituta, might be more fruitful: as ownership had faded away as a legal

75 M. Villey, L’idèe de droit subjectif et les systèmes juridiques romains, in: Revue historique de droit français et étranger 24-25 (1946-47) 201-227, 211-212. 76 Pugliese (n. Error: Reference source not found60), 237. 77 J.W. Tellegen, ‘Res incorporalis’ et les codifications modernes du droit civil, in: Labeo 40 (1994) 35-55. 78 Ibid., 51-52. 79 Bretone (n. Error: Reference source not found), 284: “Questa tesi è fantasiosa”. 80 A. Burdese, Ius consuetudine, pactum, ius e res, in: SDHI 61 (1995) 707-721, 718-719. 20 institution, being transformed into a general principle, Gaius needed to find another avenue to integrate this right into the law of transactions.

7. The Birksian Theory of Ownership

Werner Flume argues that the premise upon which the dispute concerning the Gaian classification is based is flawed. In his view, the whole discussion is the consequence of a misunderstanding which goes back to the Pandectists81. As intimated, Windscheid and his contemporaries thought that Gaius was introducing a categorisation based upon the criterion of patrimony. The corporeal things were for them those patrimonial elements that could be the object of ownership rights, whereas the incorporeal things, they too considered as patrimonial elements, were not related to ownership. This interpretation of the classification became necessary because the Pandectists did not regard the Gaian taxonomy as homogeneous, given that corporeal things cannot be patrimonial objects. For Flume, the Pandectist deduction was logical. Their original hypothesis, however, was incorrect. Gaius would bear no responsibility for the age-old confusion mentioned by Kreller, for he did not want to classify patrimonial rights, but rather objects (“Gegenstände”).

In his analysis of the concept of ownership, Peter Birks accepts the idea that the Gaian scheme contains a distinction of objects, but he reverses Flume’s conclusions, stating that both sides of the classification dealt with ownership82, not only the category of the corporeal things, as the Pandectists claimed. He contends that “Roman law distinguishes between different objects of meum esse rather than between different relationships to or interests in the material world”83. In his view, the Roman citizen would assert that the thing was his independently of the kind of thing in question. The object of the claim would be gold, land, or clothes; but also usufructs and servitudes. Gaius would have added the obligations to the list of intangibles. It follows from Birks’s theory that even obligations were for Gaius things that could be the object of ownership. The addition of the obligations would be the true innovation in the Gaian classification, because obligations were rights in personam, not rights in rem. The Gaian extension, as Birks acknowledges, was not successful. But this partial failure did not

81 W. Flume, Die Bewertung der Institutionen des Gaius, in: ZRG RA 79 (1962) 1-28, 23-24: „Das moderne Mißverständnis des Begriffspaars res corporales – incorporales beruht darauf, daß man sich von den Vorstellungen der Pandektistik nicht lösen kann”. 82 P. Birks, The Roman Law Concept of Dominium and the Idea of Absolute Ownership, in: Acta Juridica (1985) 1-37, 26-27. Note that Birks does not refer to Flume’s analysis. 83 Ibid., 27. 21 compromise the elegance of the scheme. According to Birks, Gaius proposed a system in which all assets are owned independently of their corporeality or lack thereof.

If we leave the obligations out of the picture for a while, Birks’s thesis seems to find some support in Gaius’s definition of the action in rem, which was “one in which we assert either that some corporeal thing is ours, or that we are entitled to some right, such as … an usufruct”84. Here, Gaius states that the actions in rem apply to corporeal things as well as to rights. Birks argues that both lists in Gaius’s scheme refer to objects of ownership. Consequently, for the eminent Romanist the proprietary statement of the title-holder would apply both to tangibles and intangibles. It is helpful to report the core of his view in full85:

[Gaius was] affirming, correctly, that the relationship between a man and his ius obligationis (ie a right in personam) was conceptually the same meum esse as between a man … and his horse: the difference lay in the asset owned, not in the relationship between the person and the asset … Gaius’ scheme is elegant. Assets are owned, but consist in many different forms.

To clarify the implications of Birks’s idea, a few words must be spent on the Roman proprietary claims and the transfer of ownership. According to our sources, the oldest ownership claim is the legis actio sacramento in rem. It was characterised by two assertions of ownership, a vindication and a counter-vindication. The judge had to decide which one was correct and assigned the thing accordingly86. A similar scheme was used for the transfer of ownership whenever this result was not obtained with the simple delivery of the thing. The buyer claimed that the thing was his (hunc ego hominem ex iure Quiritium meum esse aio) and the seller did not contest this allegation, so that the person who supervised the procedure (libripens or magistratus) accepted that the issue of ownership had been resolved87. This meum esse claim established the proprietary title and, according to Birks, created a relationship that was ‘conceptually the same’ for corporeal and incorporeal things. Had this been indeed the case, the Birksian conclusion that the classification referred to two categories of res, both concerning ownership rights, would be accurate. However, it does not appear that this was what Gaius had in mind. As shall be shown, ownership was not the fulcrum of his scheme.

84 Gai. inst. 4,3: In rem actio est, cum aut corporalem rem intendimus nostram esse aut ius aliquod nobis conpetere, uelut utendi aut utendi fruendi. 85 Birks (n.82Error: Reference source not found), 27. 86 Gai. inst. 4,16. 87 Gai. inst. 1,119 (mancipatio); 2,24 (in iure cessio). 22 Birks’s theory of an overarching right of ownership which would encompass both sides of the scheme encounters at least two serious obstacles. The first one is that Gaius includes obligations among the incorporeal things. The performance of an obligation could be judicially enforced with an action in personam, not with an action in rem88, and therefore it did not enable the right-holder to assert the meum esse. One might reply, using the Birksian reasoning by implication, that this was Gaius’s attempt to expand the category of incorporeal things to construe a new system of ownership. In so doing, Gaius would have enlarged the sphere of the right as to include actions in personam. This hypothesis is not convincing. It is hardly imaginable that Gaius would introduce a novel element which drastically changed the framework of the Roman private law without making any comment in support of his choice. Nowhere in the sources there is a clue which hints at such a bold move.

The second obstacle to Birks’s theory is related to the meum esse claim. Birks impliedly assumes that the differences between the intentio that was relevant for corporeal things and the intentio relating to incorporeal things were just a matter of cosmetics and did not affect the identity and structure of the in rem claim. On the basis of this assumption, he can infer that both corporeal and incorporeal things could be the object of ownership. However, in the system founded upon the legis actiones the pronunciation of the correct words was an integral part of the mechanism for the transfer of ownership. The claim, “I state that the thing is mine”, contained a technical expression, not simply generic words. Meum esse corresponded for the Romans to what modern lawyers would classify as a right of ownership. In the classical formula of the rei vindicatio, through which ownership of things could be claimed, the magistrate had to establish whether the claimant’s statement, “The thing is mine”, was correct, in which case he would have allocated the thing to the claimant89. This is not what happened for the vindication of a right such as usufruct or servitude, where the claimant asserted, “I have the right/I am entitled (mihi esse ius) to keep a given conduct”90 – for instance to use and enjoy the thing or to walk through my neighbour’s garden. The difference between the two intentiones of the actio in rem is quite manifest. Pugliese observes that the idea of ownership of rights was alien to the Roman mentality. This incompatibility would emerge in the description of the action in rem, where Gaius took care to distinguish tangible things from rights. Such distinction would not have been necessary had the action been the

88 Gai. inst. 4,2. 89 O. Lenel, Das Edictum Perpetuum, Leipzig 19273, 185-186. 90 For example, to walk through the land, or to use and enjoy the thing, ibid., 190-195. 23 same for corporeal and incorporeal things91. For Monier, the proprietary link of the claim concerning tangibles was highlighted by the use of the possessive meum, which the claimant of a right could not use92. Even if, as Burdese observes, the formulary intentio of the confessory actions of usufruct and servitude suggests a certain degree of closeness (accostamento) with the intentio of the meum esse vindicator93, still the acknowledgment of this undeniable closeness excludes necessarily any identity between the two intentiones. One can conclude, therefore, that Birks’s inference of a conceptual similarity between rights over corporeal things and rights concerning other rights is contradicted by the sources94.

8. The Role of Ownership in the Gaian Scheme

To compare material things with rights is a taxonomic mistake, which explains why the Pandectists had to transform the res corporales into patrimonial rights. Law is a social science, a creation of the human intellect to facilitate the organisation of a social community. As such, it is not interested in corporeal things, which belong to the material world. Law is concerned with abstractions, that is ideal objects. If the Gaian classification combines material objects with rights and considers all of them to be patrimonial elements, it is undeniably founded upon a classificatory error. Material things exist for the law in so far as they form the objects of legal interests and legal relations. Only those interests and relations form part of the patrimony. On this basis, the conclusion that the two Gaian lists contain incommensurable elements seems unavoidable. If the corporeal things can be the object of ownership and the incorporeal things cannot be owned, and if both tangibles and intangibles are patrimonial elements, as the Pandectists argued, the schema is indeed illogical. Yet, there is no clear indication in the Institutes that Gaius intended to introduce a categorisation which was centred on the right of ownership. Ownership and patrimony are interwoven with the classification, but not as directly as the Pandectists assumed. As Flume correctly observed, this is a classification of objects.

91 Pugliese (n. Error: Reference source not found60), 251. 92 Monier (n. Error: Reference source not found), 366. 93 Burdese (n. Error: Reference source not found80), 718. 94 Arguably, Birks threw into the academic discussion his controversial idea because, in reality, he was addressing not the Romanists, but the common lawyers. On an interpretation of Birks’s theory as an attempt to create a link between Roman law and the English common law which would allow common lawyers to integrate Roman law in their reasoning, see F. Giglio, Pandectism and the Gaian Classification of Things, in: University of Toronto Law Journal 62 (2012) 1-28, 21-23. 24 Gaius developed his taxonomy from the perspective of the legal actions. His analysis started from the formula of the action in rem, the text of which did not refer generically to a “right of ownership”, but specifically to the thing the right over which was vindicated. Thus, the formula petitoria, through which the claimant asserted his proprietary right over a thing according to the formulary system which was still in use during Gaius’s lifetime, stated that the “slave”, the “land” and so forth were the claimant’s. There was no reference to the claimant being the “owner” or claiming on the basis of his “right of ownership”. This formula contained an intentio which enabled the claimant to assert that the thing was his, but also that he was entitled to a given right. Again, the right in question had to be specified in the intentio.

Gaius implicitly confirms the strict relation between the meum esse statement and the right of ownership when he considers the conveyance of the corporeal things by mere delivery. He argues, “If I deliver clothing or gold or silver to you, be it as a consequence of a sale or a gift or for any other legal ground, the thing will be yours at once, if only I am its owner”95. The fact that I am the owner and divest myself of the right for your benefit triggers the effect that you can assert that the thing is yours. Here, Gaius avoids the cumbersome “the thing will be yours if I can assert that the thing is mine until I deliver it to you”. Similarly, he does not write, “You will be the owner if I am the owner”. Either statement would be possible, but only the avenue taken by Gaius highlights the relationship between the meum esse statement and the ownership right upon which this statement relies: The thing will be yours, that is, you will be able to assert a meum esse, if I am the owner. This passage emphasises the role of the formulae of the actions in the qualification of the right – a pragmatic approach which is coherent with Roman legal thinking.

There is no evidence that Gaius wanted to introduce a new taxonomy of things which would have profoundly modified the structure of the right of ownership. As Flume realised, this classification is not centred on ownership at all. In fact, if one agrees with Birks, Monier, and Alan Watson96 that the meum esse was a technical term for ownership, one must conclude that ownership is present in both categories of the classification. A meum esse statement could not be made by the right-holder to assert his title over most of the res listed in the category of intangibles, such as usufruct and servitude, where the claimant would only argue that he was

95 Gai. inst. 2,20: Itaque si tibi uestem uel aurum uel argentum tradidero siue ex uenditionis causa siue ex donationis siue quauis alia ex causa, statim tua fit ea res, si modo ego eius dominus sim. 96 A. Watson, The Law of Property in the Later Roman Republic, Oxford 1968, 91-92. Several other authors have supported this theory. 25 entitled to a given right (mihi esse)97, not that the right was his. However, the vindication of the inheritance (hereditas) presented a different picture. Unlike all the other claims in rem over incorporeal things, the heir was able to use a formula petitoria to assert that the inheritance belonged to him. According to Otto Lenel, the heir would claim, “The inheritance is mine”!98 Hence, the heir would use a claim with a meum esse intentio, which signals the exertion of an ownership right. There is no reason to suppose that in the limited time-span between the introduction of the Perpetual Edict and Gaius’s Institutes the formula concerning inheritance had changed. The hereditas will be examined in greater detail later on. At this stage, it suffices to point out that there is at least one instance of ownership in both categories of the classification, tangibles and intangibles. But if ownership is present in both the left- hand and the right-hand list, it cannot be the reason which moved Gaius to introduce his scheme.

9. Gaius’s Action-Based Perspective

If considered from the perspective of the claims in rem, the approach chosen by Gaius for his scheme provides a coherent picture of the law of things. And the right of ownership played a significant role in his analysis. Gaius was acquainted with the terms dominium and dominus99. But, it is contended, he did not use them because ownership appeared in both the left-hand and the right-hand list, given that all corporeal and at least one incorporeal res could be vindicated through a meum esse claim. The taxonomy was mainly influenced by Gaius’s decision to link the schema to the intentio of the actions in rem, which referred to the concrete object of the dispute, not to the abstract right: these clothes/slaves/gold bullions are mine! On the other hand, when the claim did not address proprietary issues, the intentio would mention the abstract right: ius utendi fruendi, ius eundi agendi and the like. By examining the things from the perspective of the meum esse claim, Gaius adopted a methodological approach with strong didactic value but also with a very practical connotation. His students, the main target audience of the Institutes, were going to use meum esse claims in legal litigation and understandably Gaius wanted to teach them in the most effective fashion how to connect the actions with their objects, rectius with the law of things.

97 Gai. inst. 4,3: ius aliquod nobis conpetere, uelut utendi aut utendi fruendi, eundi, agendi aquamue ducendi uel altius tollendi prospiciendiue. 98 Lenel (n.Error: Reference source not found89), 176-178: “Si paret hereditatem Publi Maeui ex iure Quiritium Auli Agerii esse”. 99 Cf. Gai. inst. 2,40. 26 If the res are considered from the standpoint of the actions in rem, ownership does not form a discrete category – a category that can be opposed to the limited real rights. The claimant in rem would state either that the slave or any other tangible was his, making use of the meum esse claim, or that he was entitled to a right of passage or other intangible, thus applying the mihi esse claim100. From this angle, the true contrast seems to be the one between homo or fundus or vestis, as tangible objects of legal claims, on the one hand and ius utendi fruendi, ius successionis or ius obligationis, as intangible objects, on the other hand. This is the sense of the alternative identified by Gaius in his description of the actiones in rem, in which the meum esse claims are opposed to the mihi esse claims. The actions in rem concern either corporeal things or rights, all of which are consequently considered objects of in rem protection. There is an evident and non-coincidental parallel between the intentio of the actiones in rem and the Gaian classification of things. In the Institutes, the law of things precedes the law of actions; and it is probably the latter which accounts for Gaius’s need to introduce a classification based upon the concept of corporeality. The significance of the actio in rem within the system of the law of actions explains why this particular classification of the law of things is so important.

Having decided that the actiones provide the angle of observation, Gaius coherently employed a terminology which was in line with that of the legal actions. This is a further confirmation that the Gaian scheme reflects primarily the intentio of the actiones in rem, which is based upon the criterion of corporeality. In the light of this criterion, the opposition between corporeal and incorporeal things is consistent with the general picture of the law of actions. All the things listed in the right-hand list, the one which contains intangibles, blend perfectly notwithstanding the difference in the respective formulae and even in the function of their particular claims.

Hereditas is the only res that contradicts the neat distinction of the couplets tangible/meum esse claim and intangible/mihi esse claim. This exception can be explained through historical development. The hereditas is an incorporeal complex of legal interests. However, as Biondo Biondi plausibly asserts, originally the hereditas comprised only corporeal things and for this reason it was treated as a res corporalis101. Biondi argues that the heir did not obtain the title to, that is the right over, the things which formed the estate; but rather the things themselves,