Atlantic Slave Trade 1500s-1600s

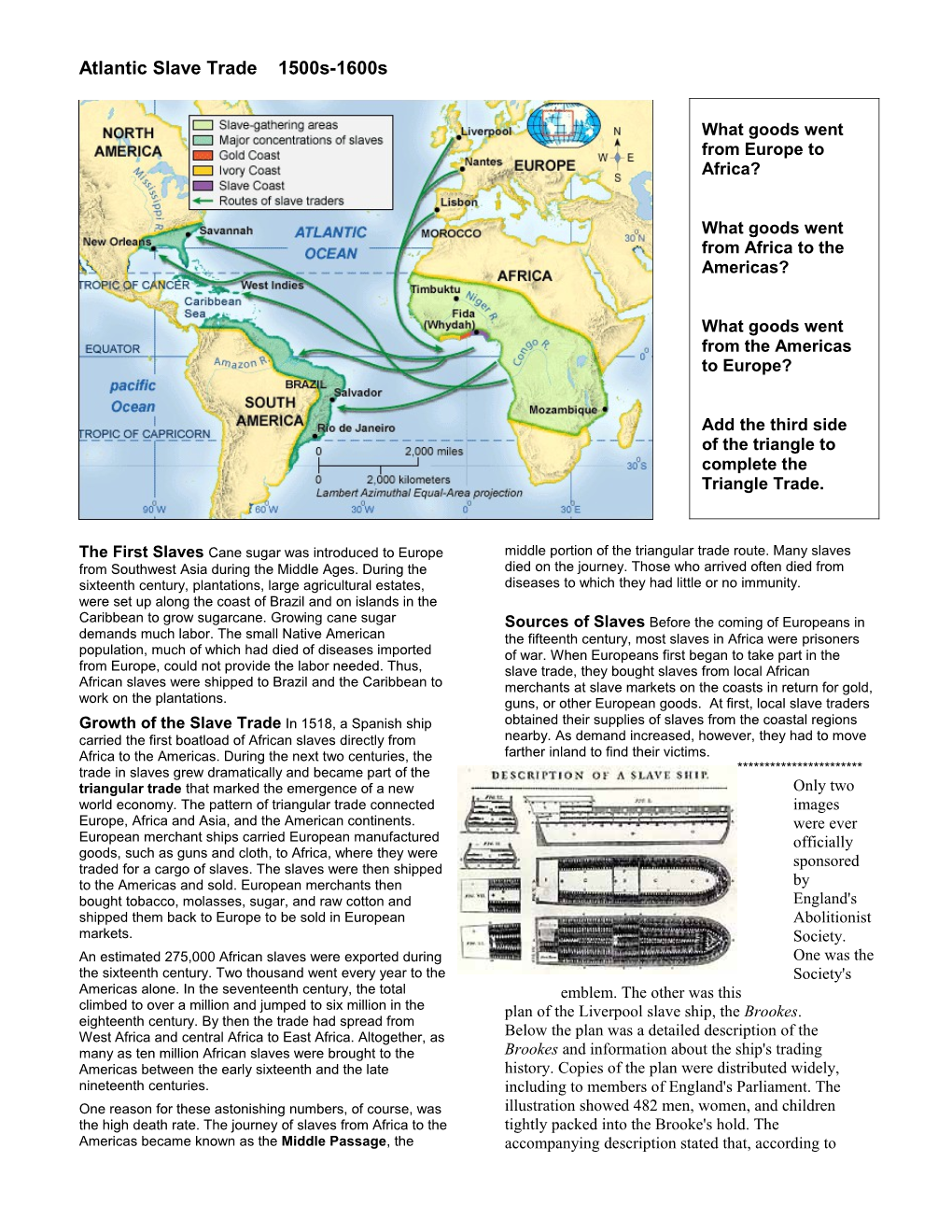

What goods went from Europe to Africa?

What goods went from Africa to the Americas?

What goods went from the Americas to Europe?

Add the third side of the triangle to complete the Triangle Trade.

The First Slaves Cane sugar was introduced to Europe middle portion of the triangular trade route. Many slaves from Southwest Asia during the Middle Ages. During the died on the journey. Those who arrived often died from sixteenth century, plantations, large agricultural estates, diseases to which they had little or no immunity. were set up along the coast of Brazil and on islands in the Caribbean to grow sugarcane. Growing cane sugar Sources of Slaves Before the coming of Europeans in demands much labor. The small Native American the fifteenth century, most slaves in Africa were prisoners population, much of which had died of diseases imported of war. When Europeans first began to take part in the from Europe, could not provide the labor needed. Thus, slave trade, they bought slaves from local African African slaves were shipped to Brazil and the Caribbean to merchants at slave markets on the coasts in return for gold, work on the plantations. guns, or other European goods. At first, local slave traders Growth of the Slave Trade In 1518, a Spanish ship obtained their supplies of slaves from the coastal regions carried the first boatload of African slaves directly from nearby. As demand increased, however, they had to move Africa to the Americas. During the next two centuries, the farther inland to find their victims. trade in slaves grew dramatically and became part of the *********************** triangular trade that marked the emergence of a new Only two world economy. The pattern of triangular trade connected images Europe, Africa and Asia, and the American continents. were ever European merchant ships carried European manufactured officially goods, such as guns and cloth, to Africa, where they were sponsored traded for a cargo of slaves. The slaves were then shipped to the Americas and sold. European merchants then by bought tobacco, molasses, sugar, and raw cotton and England's shipped them back to Europe to be sold in European Abolitionist markets. Society. An estimated 275,000 African slaves were exported during One was the the sixteenth century. Two thousand went every year to the Society's Americas alone. In the seventeenth century, the total emblem. The other was this climbed to over a million and jumped to six million in the plan of the Liverpool slave ship, the Brookes. eighteenth century. By then the trade had spread from West Africa and central Africa to East Africa. Altogether, as Below the plan was a detailed description of the many as ten million African slaves were brought to the Brookes and information about the ship's trading Americas between the early sixteenth and the late history. Copies of the plan were distributed widely, nineteenth centuries. including to members of England's Parliament. The One reason for these astonishing numbers, of course, was illustration showed 482 men, women, and children the high death rate. The journey of slaves from Africa to the tightly packed into the Brooke's hold. The Americas became known as the Middle Passage, the accompanying description stated that, according to records, as many as 609 slaves had been transported within the same space on the same ship. The Slave Trade: Some Personal Accounts

What was it like to be kidnapped, forced into a long sea journey in crowded and unsanitary conditions, and auctioned to the highest bidder in a strange land? Some eyewitness accounts were recorded to communicate the horror of the experience. Here is one man’s description of the raid that removed him from his village: . . . We were alarmed one morning, just at the break of day, by the horrible uproar caused by mingled shouts of men, and blows given with heavy sticks, upon large wooden drums. The village was surrounded by enemies, who attacked us with clubs, long wooden spears, and bows and arrows. After fighting for more than an hour, those who were not fortunate enough to run away were made prisoners. It was not the object of our enemies to kill; they wished to take us alive and sell us as slaves. I was knocked down by a heavy blow of a club, and when I recovered from the stupor that followed, I found myself tied fast with the long rope I had brought from the desert . . . We were immediately led away from this village, through the forest, and were compelled to travel all day as fast as we could walk . . . We traveled three weeks in the woods—sometimes without any path at all—and arrived one day at a large river with a rapid current. Here we were forced to help our conquerors to roll a great number of dead trees into the water from a vast pile that had been thrown together by high floods. These trees, being dry and light, floated high out of the water; and when several of them were fastened together with the tough branches of young tress, [they] formed a raft, upon which we all placed ourselves, and descended the river for three days, when we came in sight of what appeared to me the most wonderful object in the world; this was a large ship at anchor in the river. When our raft came near the ship, the white people—for such they were on board—assisted to take us on the deck, and the logs were suffered to float down the river. I had never seen white people before and they appeared to me the ugliest creatures in the world. The persons who brought us down the river received payment for us of the people in the ship, in various articles, of which I remember that a keg of liquor, and some yards of blue and red cotton cloth were the principal. Source: Charles Bell, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles bell, A Black Man. (Pittsburgh: John T Shyrock, 1854), 158-159.

The nightmare that began with kidnapping continued with the shipboard ordeal. The slave runners had only one goal: to transport as many workers as possible for sale. To them, the slaves were not passengers, but merely goods to be sold for profit. Here is one person’s description of his first experience on ship: About twenty persons were seized in our village at the time I was: and amongst there were three children so young that they were not able to walk or to eat any hard substance. The mothers of these children had brought them all the way with them and had them in their arms when we were taken on board this ship. When they put us in irons to be sent to our place of confinement in the ship, the men who fastened the irons on these mothers took the children out of their hands and threw them over the side of the ship into the water. When this was done, two of the women leaped overboard after the children –the third was already confined by a chain to another woman and could not get into the water, but in struggling to disengage herself, she broke her arm and died a few days after of a fever. One of the two women who were in the river was carried down by the weight of her irons before she could be rescued; but the other was taken up by some men in a boat and brought on board. The woman threw herself overboard one night when we were at sea. The weather was very hot whilst we lay in the river and many of us died every day; but the number brought on board greatly exceeded those who died, and at the end of two weeks, the place in which were confined was so full that no one could lie down; and we were obliged to sit all the time, for the room was not high enough for us to stand. When our prison could hold no more, the ship sailed down the river; and on the night of the second day after she sailed, I heard the roaring of the ocean as it dashed against her sides. Source: Charles Bell, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles bell, A Black Man. (Pittsburgh: John T Shyrock, 1854), 159-160. The Slave Trade: Some Personal Accounts continued

Arrival in a new world did not signal the end of suffering. After a brief time for recovering from the ravages of the voyage, the new slaves experienced auction, and the separation of families and friends. Here is one person’s recollection of the ordeal:

My brothers and sisters were bid off first, and one by one, while my mother, paralyzed with grief, held me by the hand. Her turn came and she was bought by Issac Riley of Montgomery County. Then I was offered . . . My mother, half distracted with the thought of parting forever from all her children, pushed through the crowd while the bidding for me was going on, to the spot where Riley was standing. She fell at this feet, and clung to his knees, entreating him in tones that a mother could only command, to buy her baby as well as herself, and spare to her one, at least, of her little ones . . . This man disengage[ed] himself from her with . . . violent blows and kicks . . . I must have been then between five and six years old.

Source: Josiah Henson, Father Henson’s Story of His Own Life. (Chevy Chase, Maryland: Corinth Books, Inc.., 1962). By the time that The Slave Trade was painted in 1791, George Morland was an established English artist. He gained his reputation, in part, by his compositions of childhood subjects, but he was convinced by a poet friend to make the slave trade the subject of some paintings. As the movement to abolish the African slave trade grew in Britain, Morland painted The Slave Trade, as well as other similar paintings, inspired by one of his friend's poems.

By the time that The Slave Trade was painted in 1791, George Morland was an established English artist. He gained his reputation, in part, by his compositions of childhood subjects, but he was convinced by a poet friend to make the slave trade the subject of some paintings. As the movement to abolish the African slave trade grew in Britain, Morland painted The Slave Trade, as well as other similar paintings, inspired by one of his friend's poems.

Two British captains with their barges came, With hands uplifted, he with sighs besought And quickly made a purchase of the young; The wretch that held a bludgeon o'er his head, But one was struck with Ulkna, void of shame, And those who dragg'd him, would have pity And tore her from the husband where she taught clung. By his dumb signs, to strike him instant dead.

Her faithful Chief, tho' stern in rugged war, While his dear Ulkna's sad entreating mein, Seeing his Ulkna by a White caress'd, Did but increase the brute's unchaste desire; To part with her, "and little son Tengarr!" He vaunting bears her off, her sobs are vain, His gentler feeling could not be supprest. They part the man and wife whom all admire.

Th'indignant tear steals down his ebon cheek, Image Credit: Wilberforce House, Kingston upon His gestures speak an agitated soul! Hull City Museums and Art Galleries, UK In vain his streaming eyes for mercy seek, From hearts long harden'd in this barter foul.

Only two images were ever officially sponsored by England's Abolitionist Society. One was the Society's emblem. The other was this plan of the Liverpool slave ship, the Brookes.

Below the plan was a detailed description of the Brookes and information about the ship's trading history. Copies of the plan were distributed widely, including to members of England's Parliament. The illustration showed 482 men, women, and children tightly packed into the Brooke's hold. The accompanying description stated that, according to records, as many as 609 slaves had been transported within the same space on the same ship.