The Impact of Gender Frame Sponsorship on the Frame Process in Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WBCA Announces Top 21 Candidates for the 2004 State Farm Wade Trophy 2003-04 021704

WBCA Announces Top 21 Candidates for the 2004 State Farm Wade Trophy ATLANTA, Ga. (February 17, 2004) -- With only a few weeks remaining in the regular season, the State Farm Wade Trophy Committee along with the Women's Basketball Coaches Association (WBCA) and the National Association for Girls and Women in Sport (NAGWS) today announced the top 21 candidates in contention for The State Farm Wade Trophy. Featured among the group of 21, include 2003 State Farm Wade Trophy winner, Diana Taurasi (Connecticut). Other highlighted candidates are Duke's Alana Beard, Texas trio Jamie Carey, Heather Schreiber and Stacy Stephens, Penn State's Kelly Mazzante, Stanford's Nicole Powell, and dynamic duos out of Kansas State, Nicole Ohlde and Kendra Wecker, and Minnesota's Janel McCarville and Lindsay Whalen. "All 21 candidates deserve this recognition, having made outstanding contributions to their respective teams and conferences," said WBCA CEO, Beth Bass. "Any player selected from this awesome group of talent would be an excellent representative of Lily Margaret Wade and The State Farm Wade Trophy." Although 21 players have been recognized, other players are still eligible to be considered for the State Farm Wade Trophy. One player that was not a State Farm Wade Trophy Preseason Candidate and has been added to the list for her outstanding performance this season is the University of Florida's Vanessa Hayden. The candidates were selected by a vote of committee members comprised of leading basketball coaches, journalists, and basketball administrators. Members of the committee will select the winner of The State Farm Wade Trophy from the 10-member Kodak All-America Team and will be announced during the WBCA National Convention, April 3-6, New Orleans, LA. -

National Basketball Association Official

NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION OFFICIAL SCORER'S REPORT FINAL BOX 8/4/2009 Key Arena, Seattle, WA Officials: #17 Scott Twardoski, #42 Roy Gulbeyan, #44 Felicia Grinter Time of Game: 2:10 Attendance: 6,728 VISITOR: Phoenix Mercury (16-6) NO PLAYER MIN FG FGA 3P 3PA FT FTA OR DR TOT A PF ST TO BS PTS 23 Cappie Pondexter F 35:28 6 19 0 4 4 4 3 5 8 5 3 0 4 1 16 43 Lecoe Willingham F 22:33 2 6 0 0 0 0 2 4 6 1 4 0 5 0 4 50 Tangela Smith C 32:01 5 12 4 6 0 0 1 7 8 0 4 1 0 1 14 3 Diana Taurasi G 36:15 4 11 2 5 9 11 2 4 6 2 3 0 2 1 19 2 Temeka Johnson G 30:36 6 12 3 5 0 0 0 3 3 7 4 0 0 0 15 24 DeWanna Bonner 23:54 2 7 0 1 3 4 2 2 4 0 3 2 1 0 7 11 Ketia Swanier 13:29 2 2 1 1 0 0 1 2 3 2 0 2 0 0 5 13 Penny Taylor 19:19 6 9 2 3 4 4 2 0 2 4 4 2 3 0 18 33 Kelly Mazzante 9:06 1 4 1 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 1 3 21 Brooke Smith 2:19 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 30 Nicole Ohlde DND - Surgery, left wrist TOTALS: 34 82 13 29 20 23 14 27 41 21 27 7 15 4 101 PERCENTAGES: 41.5% 44.8% 87.0% TM REB: 13 TOT TO: 16 (14 PTS) HOME: SEATTLE STORM (12-8) NO PLAYER MIN FG FGA 3P 3PA FT FTA OR DR TOT A PF ST TO BS PTS 2 Swin Cash F 40:04 4 16 0 0 4 4 2 9 11 2 4 1 4 1 12 15 Lauren Jackson F 40:20 4 13 0 1 10 10 5 6 11 2 2 0 0 3 18 20 Camille Little C 42:31 9 13 1 1 1 4 1 3 4 0 2 3 2 0 20 10 Sue Bird G 40:04 5 13 2 7 1 1 0 4 4 5 2 1 4 0 13 30 Tanisha Wright G 40:46 8 15 1 1 8 10 2 3 5 7 5 2 3 0 25 14 Shannon Johnson 11:03 0 2 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 1 0 0 0 33 Janell Burse 7:09 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 2 0 2 4 Katie Gearlds 3:03 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 Suzy Batkovic-Brown DNP - Coach's Decision 43 Ashley Robinson DNP - Coach's Decision 44 Ashley Walker DND - Jammed Right Toe TOTALS: 31 75 4 11 24 29 10 26 36 17 19 9 15 4 90 PERCENTAGES: 41.3% 36.4% 82.8% TM REB: 10 TOT TO: 15 (20 PTS) SCORE BY PERIODS 1 2 3 4 1OT FINAL Mercury 23 22 19 20 17 101 STORM 23 20 16 25 6 90 Technical Fouls - Individual Mercury: NONE STORM (1): Jackson 1:32 1st Pts. -

Lady Tigers Basketball

Lady Tigers Basketball 2013-14 SCHEDULE/RESULTS Games Kerr Activities Center (2,700) - Ada, Okla. Nov. 9 - East Central vs. Southwestern Christian - 7 p.m. Date Opponent Time 1-2 Nov. 9 Southwestern Christian 7 p.m. Nov. 12 - East Central vs. St. Gregory’s - 7 p.m. Nov. 12 St. Gregory’s 7 p.m. Nov. 16 Rogers State 2 p.m. Nov. 21 *Ouachita Baptist 5:30 p.m. at Nov. 23 *Henderson State 2 p.m. Nov. 25 St. Gregory’s 7 p.m. Dec. 5 *Harding 5:30 p.m. 0-0 (0-0 GAC) 0-1 (0-0 SAC) 0-1 (0-0 SAC) Dec. 7 *Arkansas Tech 2 p.m. ECU’s interim head coach: Emily Holombek SWCU’s head coach: Becky Mitchell Dec. 14 Midwestern State 2 p.m. Holombek’s career record: 0-0 / 1st Season Mitchell’s career record: NA Holombek’s ECU record: Same Mitchell’s Record at SWCU: NA Dec. 17 Mid-American Christian 7 p.m. Jan. 2 *Arkansas-Monticello 5:30 p.m. Media Information Series Record: ECU leads, 14-2 Radio: KXFC (105.5 FM), with Kenny Morrison Last Meeting: Nov. 26, 2012 - L, 74-76 (A) Jan. 4 *Southern Arkansas 2 p.m. and online at www.ECUTigers.com Live Stats: Available on the women’s basketball Jan. 19 *Northwestern Oklahoma State 5:30 p.m. SGU’s head coach: Josiah White schedule page at www.ECUTigers.com White’s career record: 0-0 / 1st Season Jan. 11 *Southwestern Oklahoma State 2 p.m. Live Video: Available on the women’s basketball White’s Record at SGU: Same schedule page at www.ECUTigers.com Jan. -

National Basketball Association Official

NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION OFFICIAL SCORER'S REPORT FINAL BOX Tuesday, June 21, 2016 STAPLES Center, Los Angeles, CA Officials: #55 Eric Brewton, #62 Jeff Wooten, #70 Aaron Smith Game Duration: 2:05 Attendance: 9,112 VISITOR: Minnesota Lynx (13-0) POS MIN FG FGA 3P 3PA FT FTA OR DR TOT A PF ST TO BS +/- PTS 23 Maya Moore F 19:36 3 9 0 3 2 2 1 5 6 3 4 0 2 0 0 8 32 Rebekkah Brunson F 21:47 3 5 0 0 6 6 5 4 9 1 1 2 1 2 0 12 34 Sylvia Fowles C 28:34 3 5 0 0 1 4 1 10 11 2 3 1 3 2 0 7 33 Seimone Augustus G 29:25 6 16 1 1 0 0 2 1 3 0 4 0 3 0 0 13 13 Lindsay Whalen G 24:27 3 8 0 0 0 1 0 2 2 3 1 1 3 0 0 6 21 Renee Montgomery 23:16 2 8 2 7 0 0 0 2 2 4 1 1 1 1 0 6 3 Natasha Howard 16:11 6 9 0 1 0 0 1 1 2 0 1 1 0 0 0 12 7 Jia Perkins 23:15 3 8 0 2 2 3 1 5 6 2 1 4 2 0 0 8 4 Janel McCarville 13:30 0 2 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 4 3 2 0 0 0 0 14 Bashaara Graves DNP - Coach's Decision 24 Keisha Hampton DNP - Coach's Decision 200:00 29 70 3 15 11 16 12 30 42 19 19 12 15 5 0 72 41.4 % 20.0 % 68.8 % TM REB: 9 TOT TO: 18 (17 PTS) HOME: LOS ANGELES SPARKS (11-1) POS MIN FG FGA 3P 3PA FT FTA OR DR TOT A PF ST TO BS +/- PTS 17 Essence Carson F 27:35 5 11 1 3 0 0 0 1 1 2 2 3 2 0 0 11 30 Nneka Ogwumike F 28:39 2 3 0 0 5 6 0 6 6 1 4 0 2 0 0 9 3 Candace Parker C 33:11 3 13 0 3 3 8 4 4 8 6 1 2 4 1 0 9 0 Alana Beard G 36:46 5 9 0 0 0 1 1 3 4 2 2 3 3 1 0 10 20 Kristi Toliver G 33:31 5 13 4 8 6 7 0 4 4 1 2 1 1 0 0 20 12 Chelsea Gray 11:18 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 1 0 1 3 1 0 0 42 Jantel Lavender 21:59 4 9 0 0 0 0 0 3 3 2 3 1 1 0 0 8 23 Ana Dabovic 5:59 0 1 0 0 2 2 0 1 1 0 2 0 1 0 0 2 21 Ann Wauters 1:02 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 10 Evgeniia Belyakova DND - Broken left ring finger. -

WBCA and Kodak Announce NCAA Division I Kodak/WBCA All-America Finalists

WBCA and Kodak Announce NCAA Division I Kodak/WBCA All-America Finalists ATLANTA, Ga. (March 10, 2004) -- The Women's Basketball Coaches Association (WBCA) and Eastman Kodak Company today announced the finalists for the 2004 NCAA Division I Kodak/WBCA All-America Basketball Team. WBCA head coach members from each of the eight WBCA geographical regions determine finalists. Once selected, all finalists are considered for Kodak/WBCA All-America Team honors. Finalists for the NCAA Division I Kodak/WBCA All-America Team are listed below by region. Region Jacqueline University of Notre Dame Jr. F 6'2" 1 Batteast Rebekkah Georgetown University Sr. F 6'3" Brunson Amber Jacobs Boston College Sr. G 5'8" Cathy Joens George Washington University Grad G 5'11" Cappie Pondexter Rutgers University Jr. G 5'9" Diana Taurasi University of Connecticut Sr. G 6'0" Region 2 Alana Beard Duke University Sr. G/F 5'11" Kaayla Chones North Carolina State University Sr. C 6'3" Katie Feenstra Liberty University Jr. C 6'8" Camille Little University of North Carolina Fr. F 6'1" Lakeia Stokes Clemson University Sr. G/F 6'0" Iciss Tillis Duke University Sr. F 6'5" Region Seimone Louisiana State University So. G/F 6'1" 3 Augustus Shameka University of Arkansas Sr. G/F 6'1" Christon Shyra Ely University of Tennessee Jr. F 6'2" Vanessa Hayden University of Florida Sr. C 6'4" Christi Thomas University of Georgia Sr. F/C 6'5" Le'Coe Auburn University Sr. F 6'0" Willingham Region 4 Sandora Irvin Texas Christian University Jr. -

2003 NCAA Women's Basketball Records Book

Champ_WB02 10/31/02 4:49 PM Page 131 Championships Division I Championship .................................. 132 Division II Championship.................................. 142 Division III Championship................................. 144 Champ_WB02 10/31/02 4:49 PM Page 132 132 DIVISION I CHAMPIONSHIP Division I Championship Colorado 88, Southern U. 61 1-4, 1-2, 3, 3; Wynter Whitley 5-11, 4-4, 8, 14. Tulane 73, Colorado St. 69 TOTALS: 28-73, 11-14, 38 (5 team), 71. Stanford 76, Weber St. 51 Oklahoma: Caton Hill 5-11, 3-3, 6, 14; Jamie Duke 95, Norfolk St. 48 Talbert 3-5, 2-2, 5, 8; Rosalind Ross 7-14, 8-10, 10, TCU 55, Indiana 45 26; LaNeishea Caufield 4-13, 4-4, 3, 12; Stacey UC Santa Barb. 57, Louisiana Tech 56 Dales 6-13, 2-2, 6, 17; Dionnah Jackson 3-4, 2-2, 4, Texas 60, Wis.-Green Bay 55 9; Shannon Selmon 0-0, 0-0, 0, 0; Stephanie Simon 0- Cincinnati 76, St. Peter’s 63 (OT) 0, 0-0, 0, 0; Lauren Shoush 0-1, 0-0, 1, 0; Lindsey South Carolina 69, Liberty 61 Casey 0-1, 0-0, 1, 0; Stephanie Luce 0-0, 0-0, 0, 0; Drake 87, Syracuse 69 Kate Scott 0-0, 0-0, 1, 0. TOTALS: 28-61, 21-24, 42 Baylor 80, Bucknell 56 (5 team), 86. Halftime: Oklahoma 40, Duke 28. Three-point field SECOND ROUND goals: Duke 4-20 (Matyasovsky 0-1, Tillis 1-4, Krapohl Connecticut 86, Iowa 48 1-2, Beard 1-4, Gingrich 1-4, Mosch 0-1, Whitley 0- Penn St. -

History Facilities Ncaa Sec Records Media Info

GENERAL STAFF PLAYERS STAFF REVIEW HISTORY 73 FACILITIES NCAA SEC RECORDS MEDIA INFO RECORDS SEC HISTORY UTSPORTS.COM HISTORYHISTORY ALL-TIME ROSTER A NAME NO YEARS STATUS HOMETOWN/HIGH SCHOOL POS HT GMS PPG RPG Jody Adams 3 1989-93 Graduate Cleveland, TN/Bradley Central G 5-5 107 6.7 1.7 Nicky Anosike 55 2004-08 Graduate Staten Island, NY/St. Peter’s F/C 6-4 146 7.5 6.3 Alberta Auguste 33 2006-08 Graduate Marrero, LA/John Ehret F 5-11 75 5.1 2.6 Lauren Avant 12 2010-11 Transfer Memphis, TN/Lausanne Collegiate School G 5-9 19 2.6 1.3 B Suzanne Barbre 34 1974-78 Graduate Morristown, TN/Morristown West G 5-8 64 13.5 4.2 Briana Bass 1 2008-12 Graduate Indianapolis, IN/North Central G 5-2 118 2.1 0.8 Vicki Baugh 21 2007-12 Graduate Sacramento, CA/Sacramento F 6-4 111 5.8 5.1 Angie Bjorklund 5 2007-11 Graduate Spokane Valley, WA/University G/F 6-0 132 11.1 2.9 Shannon Bobbitt 00 2006-08 Graduate New York, NY/Bergtraum G 5-2 74 9.3 2.3 Cindy Boggs 24 1974-75 Graduate Ducktown, TN G 5-6 Fonda Bondurant 12 1975-77 Graduate South Fulton, TN/South Fulton G 5-6 30 2.1 0.9 Sherry Bostic 14 1984-86 Transfer LaFollette, TN/Campbell County F 5-11 51 3.1 1.9 Nancy Bowman 12 1972-75 Graduate Lenoir City, TN G 5-3 Gina Bozeman 20 1981 Transfer Sylvester, GA/Worth Academy G 5-6 8 1.3 0.4 Dianne Brady 20 1973-75 Graduate Calhoun, TN G 5-2 Alyssia Brewer 33 2008-11 Transfer Sapulpa, OK/Sapulpa F 6-3 87 6.9 4.6 Cindy Brogdon 44 1977-79 Graduate Buford, GA/Greater Atlanta Christian F 5-10 70 20.8 6.0 Lou Brown 21 2018- Active Melbourne, AUST/Australian Inst. -

Aug. 13 Vs. Phoenix.Indd

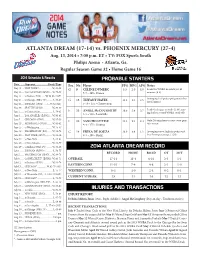

ATLANTA DREAM (17-14) vs. PHOENIX MERCURY (27-4) Aug. 13, 2014 • 7:00 p.m. ET • TV: FOX Sports South Philips Arena • Atlanta, Ga. Regular Season Game 32 • Home Game 16 2014 Schedule & Results PROBABLE STARTERS Date .........Opponent ....................Result/Time Pos. No. Player PPG RPG APG Notes May 11 .....NEW YORK^ .......................W, 63-58 G 9 CÉLINE DUMERC 3.3 2.0 4.0 Leads the WNBA in assists per 40 May 16 .....SAN ANTONIO (SPSO) ....W, 79-75 5-7 • 145 • France minutes (8.9) May 17 .....at Indiana (FSS) .......W, 90-88 (2OT) Averaging 15.9 points per game in her May 24 .....at Chicago (NBA TV) .......... L, 73-87 G 15 TIFFANY HAYES 13.2 3.0 2.6 last 15 games May 25 .....INDIANA (SPSO) ...... L, 77-82 (OT) 5-10 • 155 • Connecticut May 30 .....SEATTLE (SPSO) ................W, 80-69 F 35 ANGEL McCOUGHTRY 19.0 5.4 3.7 Leads the league in steals (2.48), aim- June 1 .......at Connecticut .......................L, 76-85 ing for her second WNBA steals title June 3 .......LOS ANGELES (ESPN2) ....W, 93-85 6-1 • 160 • Louisville June 7 .......CHICAGO (SPSO) ..............W, 97-59 F 20 SANCHO LYTTLE 12.4 9.2 2.4 Only Dream player to start every game June 13 .... MINNESOTA (SPSO) .........W, 85-82 6-4 • 175 • Houton this season June 15 .... at Washington ......................W, 75-67 June 18 .... WASHINGTON (FSS) ........W, 83-73 C 14 ERIKA DE SOUZA 13.9 8.9 1.2 Averaging career highs in points and June 20 .... NEW YORK (SPSO) ...........W, 85-64 6-5 • 190 • Brazil free throw percentage (.720) June 22 ... -

2006 NCAA Division I Women's Basketball Championship

DIVISION I WOMEN’S Basketball DIVISION I WOMEN’S BASKETBALL History Team Results Championship Championship Year Champion (Record) Coach Score Runner-Up Site Game Attendance Total Attendance 1982 ............. Louisiana Tech (35-1) Sonja Hogg 76-62 Cheyney Norfolk, Va. 9,531 56,320 1983 ............. Southern California (31-2) Linda Sharp 69-67 Louisiana Tech Norfolk, Va. 7,387 62,020 1984 ............. Southern California (29-4) Linda Sharp 72-61 Tennessee Los Angeles 5,365 77,497 1985 ............. Old Dominion (31-3) Marianne Stanley 70-65 Georgia Austin, Tex. 7,597 98,569 1986 ............. Texas (34-0) Jody Conradt 97-81 Southern California Lexington, Ky. 5,662 90,177 1987 ............. Tennessee (28-6) Pat Summitt 67-44 Louisiana Tech Austin, Tex. 15,615 104,412 1988 ............. Louisiana Tech (32-2) Leon Barmore 56-54 Auburn Tacoma, Wash. 8,719 122,165 1989 ............. Tennessee (35-2) Pat Summitt 76-60 Auburn Tacoma, Wash. 9,758 154,651 1990 ............. Stanford (32-1) Tara VanDerveer 88-81 Auburn Knoxville, Tenn. 20,023 177,820 1991 ............. Tennessee (30-5) Pat Summitt 70-67 (ot) Virginia New Orleans 7,865 153,014 1992 ............. Stanford (30-3) Tara VanDerveer 78-62 Western Ky. Los Angeles 12,072 187,417 1993 ............. Texas Tech (31-3) Marsha Sharp 84-82 Ohio St. Atlanta 16,141 217,910 1994 ............. North Carolina (33-2) Sylvia Hatchell 60-59 Louisiana Tech Richmond, Va. 11,966 266,154 1995 ............. Connecticut (35-0) Geno Auriemma 70-64 Tennessee Minneapolis 18,038 248,534 1996 ............. Tennessee (32-4) Pat Summitt 83-65 Georgia Charlotte, N.C. -

Women's Basketball Award Winners

WOMEN’S BASKETBALL AWARD WINNERS All-America Teams 2 National Award Winners 15 Coaching Awards 20 Other Honors 22 First Team All-Americans By School 25 First Team Academic All-Americans By School 34 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners By School 39 ALL-AMERICA TEAMS 1980 Denise Curry, UCLA; Tina Division II Carla Eades, Central Mo.; Gunn, BYU; Pam Kelly, Francine Perry, Quinnipiac; WBCA COACHES’ Louisiana Tech; Nancy Stacey Cunningham, First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Wom en’s Lieberman, Old Dominion; Shippensburg; Claudia Basket ball Coaches Association. Was sponsored Inge Nissen, Old Dominion; Schleyer, Abilene Christian; by Kodak through 2006-07 season and State Jill Rankin, Tennessee; Lorena Legarde, Portland; Farm through 2010-11. Susan Taylor, Valdosta St.; Janice Washington, Valdosta Rosie Walker, SFA; Holly St.; Donna Burks, Dayton; 1975 Carolyn Bush, Wayland Warlick, Tennessee; Lynette Beth Couture, Erskine; Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Woodard, Kansas. Candy Crosby, Northern Ill.; Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, 1981 Denise Curry, UCLA; Anne Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Donovan, Old Dominion; Okla. Harris, Delta St.; Jan Pam Kelly, Louisiana Tech; Division III Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Irby, William Penn; Ann Kris Kirchner, Rutgers; Kaye Cross, Colby; Sallie Meyers, UCLA; Brenda Carol Menken, Oregon St.; Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Cindy Noble, Tennessee; Elizabethtown; Deanna Debbie Oing, Indiana; Sue LaTaunya Pollard, Long Kyle, Wilkes; Laurie Sankey, Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. Beach St.; Bev Smith, Simpson; Eva Marie St.; Susan Yow, Elon. Oregon; Valerie Walker, Pittman, St. Andrews; Lois 1976 Carol Blazejowski, Montclair Cheyney; Lynette Woodard, Salto, New Rochelle; Sally St.; Cindy Brogdon, Mercer; Kansas. -

Suzie Mcconnell-Serio, University of Pittsburgh 9 A.M

22001166 UUSSAA BBaasskkeettbbaallll WWoommeenn’’ss UU1188 NNaattiioonnaall TTeeaamm JJuullyy 1133--1188,, 22001166 •• VVaallddiivviiaa,, CChhiillee U18 Scheduulee SStaff Head Coach Saturday,, July 2 Suzie McConnell-Serio, University of Pittsburgh 9 a.m. Practice 5 p.m. Practice Assistant Coach Kamie Ethridge, University of Northern Colorado Sunday,, July 3 9 a.m. Practice Assistant Coach 6 p.m. Practice Charlotte Smith, Elon University Monday,, July 4 Athlletic Trainer 11 a.m. Practice Ed Ryan, Colorado Springs, Colorado Tuesday,, July 5 Team Leaders 10 a.m. Practice Carol Callan, USA Basketball 6 p.m. Scrimmage: USA - Japan Ohemaa Nyanin, USA Basketball Wednesday, July 6 Press Officer 10 a.m. Practice Jenny Johnston, USA Basketball 5 p.m. Scrimmage: USA - Japan Thursday,, July 7 10 a.m. Practice MMediia Poolicy 5 p.m. Scrimmage: USA - Japan Media members must be credentialed to attend Friday,, July 8 training camp. For credentialing, please email Jenny 10 a.m. Practice Johnston at: [email protected] 5 p.m. Practice/Scrimmage Athletes and coaches are available for interviews after each session. All interviews should be arranged through a Saturday,, July 9 member of the USA Basketball communications staff. Depart for Chile Sunday,, July 10 TBD Practice Monday,, July 11 TBD Practice / Scrimmage Canada Tuesday,, July 12 TBD Practice • All sessions are closed to the public. • All U.S. sessions will take place at the United States Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colorado. • Media must be credentialed to attend. • U.S. times are Mountain Daylight Time. TTaabbllee ooff Coonnteennttss Generall Information Event History Training Schedule .............................................................. IFC 2014 Recap ......................................................................... -

08-09 WBB Media Guide

PLAYERS Hawk Profiles The Hawk Will Die! Never CAREER HIGHS Points: ..............................................................8, vs. Massachusetts, 2/27/13 Field Goals:......................................................3, vs. Massachusetts, 2/27/13 Field Goals Att:................................................5, vs. Massachusetts, 2/27/13 3-Pt Field Goals:.........................................................................Yet To Come 3-Pt Field Goals Att: ...................................................1, vs. UMBC, 12/29/12 Free Throws:.......................................2, 2x, last vs. Massachusetts, 2/27/13 Free Throws Att:..........................................4, vs. Savannah State, 12/21/12 Offensive Rebounds: .............................................1, 2x, last at VCU, 2/6/13 Defensive Rebounds: .....................................2, vs. Massachusetts, 2/27/13 Total Rebounds: .................................2, 2x, last vs. Massachusetts, 2/27/13 Assists:........................................................................1, vs. UMBC, 12/29/12 Blocks:.........................................................................................Yet To Come Steals:..........................................................................2, vs. UMBC, 12/29/12 Minutes: ...........................................................8, vs. Massachusetts, 2/27/13 32 2013-14 Saint Joseph’s University Women’s Basketball Hawk Profiles Ciara Andrews #21 Sophomore • 5-9 • Guard Glenside, Pa. / Cheltenham 2012-13: Appeared