Military Resistance: [email protected] 8.9.14 Print it out: color best. Pass it on. Military Resistance 12H2

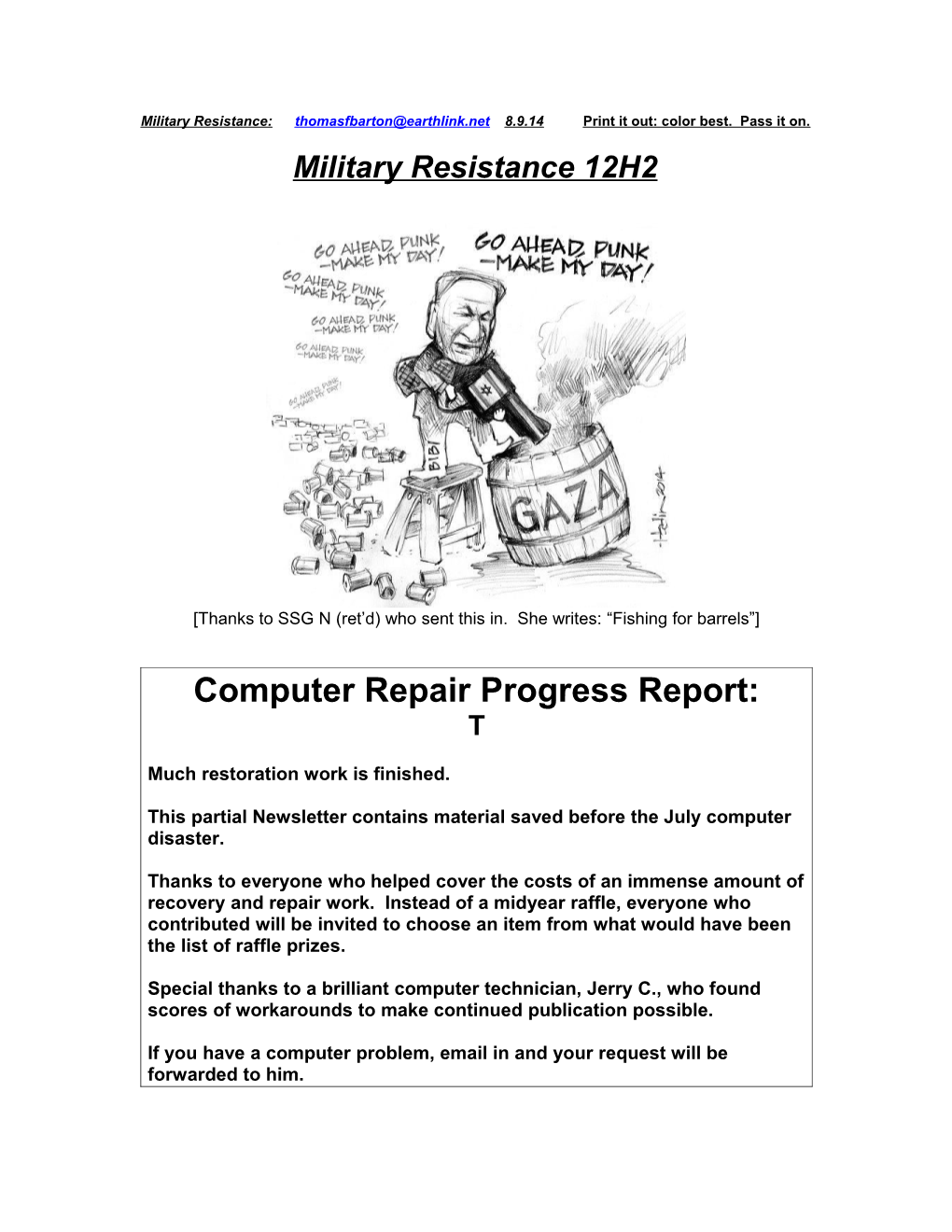

[Thanks to SSG N (ret’d) who sent this in. She writes: “Fishing for barrels”]

Computer Repair Progress Report: T

Much restoration work is finished.

This partial Newsletter contains material saved before the July computer disaster.

Thanks to everyone who helped cover the costs of an immense amount of recovery and repair work. Instead of a midyear raffle, everyone who contributed will be invited to choose an item from what would have been the list of raffle prizes.

Special thanks to a brilliant computer technician, Jerry C., who found scores of workarounds to make continued publication possible.

If you have a computer problem, email in and your request will be forwarded to him. “There Are Folks That Insist Iraq Is A Security Threat, And We Must Intervene To Protect Ourselves” “Horse Shit” “If You Cannot See The Flaws In That Argument, Let Me Help You Out”

CAPT. DAVID J. LENZI II

July 21, 2014 by CAPT. DAVID J. LENZI II, Army Times.

The writer is an active-duty Engineer officer who has deployed three times to Iraq, including as an adviser to the Iraqi army.

********************************************************************************

There seems to be an awful lot of people who think any excuse to travel to a foreign country and kill people is a good one.

It’s a shame that the two-edged sword of technologically enabled communication cuts in a way that provides them a platform from which to spew this nonsense.

Killing people for fun/sport is the province of sociopaths, not the measured, responsible foreign policy of a nation that envisions itself as a world power.

I cannot be sure how many of these mental invalids are members of the Armed Services, but they don’t belong here.

Our professional obligation is to defend the United States. Ultimately, this viewpoint makes us look like 21st century Barbarian hordes — that’s not a good thing.

The second most objectionable category, to my mind, are the folks who think we left Iraq too soon and that more ’MURICA is what that country needs.

These folks often have bouts of amnesia where they forget that the withdraw plan followed by our sitting president was approved by his predecessor. They also tend to suffer from the illusion that a small cadre of U.S. personnel working with the Iraqi military can somehow significantly impact the culture of Iraq and the course of its government.

They seem to think that the U.S. of A. needs to be involved in the business of determining who should govern other countries and then taking military action to install/ supplant/support their leader/government of choice.

Ignoring, for a moment, the blatant amorality of this concept, let’s look at the historical record.

How did we do in Vietnam?

What about Iraq when Hussein rose to power?

How about Afghanistan, in the midst of yet another massively corrupt election sequence staged by a government that is completely ineffectual at the business of governing (kind of answered it, sorry)? The U.S. has no real demonstrated capacity for playing the long game — establishing a legitimate and capable government abroad.

We play the short game and use military power to install a government we think will work out for us near term. There is a difference between isolationism and objection to military intervention as the primary/sole foreign policy option.

Though not a mutually exclusive group, there are also folks that insist Iraq is a security threat, and we must intervene to protect ourselves.

First off, horse shit.

If you cannot see the flaws in that argument, let me help you out.

Why is Iraq a supposed security threat? Terrorists, one assumes, since it certainly isn’t the capacity of its military to project power abroad.

So, if we buy into the idea that any country that might potentially shelter or sponsor terrorists is a grave threat that requires military action, why would we start with Iraq?

Indeed, Iraq is such a small potato, why would we even bother with it at all?

As we learned firsthand while fighting in Iraq, Iran is a far larger and more dangerous sponsor of terrorism.

We discuss the threat of Al Qaeda frequently, but seem to remain mum on the point that our “friends” in Saudi Arabia are the single largest sponsor of that particular organization, whether on an official basis or no. Pakistan harbors terrorists (I seem to recall finding someone of importance there not long ago ... Bin ...Bin ... Bin something) has confirmed nuclear weapons and is every bit as dysfunctional as Iraq in some respects.

Libya? Lebanon? Now we’re discussing known shelters for terror camps and terrorists, but seemingly not worthy of U.S. military intervention. On that note, if controlling terrorism is our goal, the idea of a proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia in Iraq should make us giddy with excitement.

Two major terror sponsors spending their money to kill one another in their backyard — it’s like they’re doing our job for us.

Think about that for a moment — the usual bad actors and suspects focused on each other instead of us for a little while. We ought to be thankful, not figuring out a way to put ourselves in the middle of their shit storm.

The hard reality of the Middle East is not a reality that we can deal with effectively. We have this American-centric view that holds forth that we are the solution and some more exposure to us will somehow heal the woes of Iraq.

It just isn’t true. It’s not true in Afghanistan either.

Iraq comes from a very different place culturally. They have a huge number of unresolved issues underlying their internal politics.

There is nothing we can do to fix those things. It’s not a car or a plane where just swapping some parts around yields the desired results when it isn’t working correctly.

It’s a country and a people that were thrown together without their own consent (or even participation in the process) that is now attempting to define its own identity. They need to work that out for themselves — call it a civil war, if you like, but they need to settle their own differences. That is what they are doing right now.

I know we’d like everyone to sit around a table and talk their differences out, but not everyone does things that way.

Troops in Iraq are not going to fix that country or strike a resounding blow against terrorism or make the world a safer place.

Troops in Iraq are just more blood and treasure we don’t need to spend on a cause we’re not seeing any return on for our investment.

AFGHANISTAN WAR REPORTS

Two U.S. Soldiers Killed By IED In Mirugol Kalay

July 24, 2014 AP & U.S. Department of Defense News Release Release No: NR-390-14

Two U.S. soldiers have been killed in Afghanistan. They died July 24, in Mirugol Kalay, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan, of wounds suffered when their vehicle was attacked by an improvised explosive device. These soldiers were assigned 1st Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division, Fort Carson, Colo.

Killed were:

Staff Sgt. Benjamin G. Prange, 30, of Hickman, Neb.; and

Pfc. Keith M. Williams, 19, of Visalia, Calif.

Staff Sgt. David H. Stewart Killed In Afghanistan

Jun 23, 2014 NBCUniversal Media, LLC

A Marine from Stafford County, Virginia, was killed last week while on deployment in Afghanistan.

Staff Sgt. David H. Stewart, 34, died Friday while supporting combat operations in the Helmand province of the country, the Department of Defense announced.

Lance Cpl. Brandon J. Garabrant, 19, of Peterborough, New Hampshire, and Lance Cpl. Adam R. Wolff, 25, of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, were also killed as a result of the hostile incident.

All three were all assigned to the 2nd Combat Engineer Battalion (Forward) in the 2nd Marine Division.

Stewart most recently deployed to Afghanistan in April, while Garabrant and Wolff deployed in March.

It was his fifth deployment in 10 years, and his second in Afghanistan. He was serving as a platoon sergeant for the 2nd Combat Engineer Battalion, 2nd Marine Division, II Marine Expeditionary Force.

He also completed three tours of duty in Iraq after joining the Marines in June 2004. He was promoted to staff sergeant in 2010.

Stewart graduated from North Stafford High School and still considered Stafford his home despite living near Camp Lejuene in North Carolina, said his father, Nelson Stewart.

Nelson, who also served in the Marines, told News4's David Culver that his son was a "warm, loving person."

David Stewart also left behind his wife, Kristine, and two young children. "We've been together since we were teenagers and he's always been positive," Kristine Stewart said. "It didn't matter what was going on. All the joys in our life and then the hardships that come with five deployments; he just was my rock."

It's painful to think their two young children won't have their father with them as they grow up, she said. She wishes they would be able to see for themselves what a wonderful man he was.

"...David's probably up in heaven right now saying, 'I'm so sorry, sweetheart. I love you so much. And I'm so sorry,' because he always put us first," Kristine Stewart said.

POLITICIANS REFUSE TO HALT THE BLOODSHED THE TROOPS HAVE THE POWER TO STOP THE WAR

Camp Gibson Attack Kills Five Guards

Jul 22 By Ghanizada, Khaama Press

The US Embassy in Kabul strongly condemned the attack in capital Kabul which left at least five foreign security guards dead.

The attack took place around 6:30 am local time after a suicide bomber detonated his explosives near the entrance gate of the Camp Gibson, security officials said.

The Taliban militants group claimed responsibility behind the incident and said several foreign forces were killed or injured following the attack.

Taliban group spokesman, Zabiullah Mujahid said an important intelligence compound of the foreign forces was targeted in the attack.

Taliban Militants Occupy Shakh

July 22 (Xinhua)

Taliban militants after three days of fighting with security personnel have made headway and occupied land in Qaisar district of Faryab province 425 km northwest of Kabul, police said Tuesday. "Taliban rebels attacked security check points in the western part of Qaisar district three days ago, which triggered heavy battle between the two sides and the militants after three days of fighting were able to occupy Shakh area on Monday night," deputy provincial police chief Mohammad Naeem Andarabi told reporters here.

More Resistance Action

July 24, 2014 AP

A bomber detonated his payload at a checkpoint in the eastern Nangarhar province, killing a local police commander and his bodyguard, according to police spokesman Hazrat Hussain Mashraqiwal.

He said the bomber shook hands with the commander before the explosion. The Taliban claimed responsibility for the attack in a media statement

*********************************

Jul 26 By Ghanizada, Khaama Press

An Afghan army national army (ANA) officer was martyred following an explosion in capital Kabul early Saturday.

According to the security officials the incident took place around 7:00 am local time in Abdul Haq Square.

Hashmatullah Stanekzai, spokesman for the Kabul police department, said another Afghan army officer was also injured following the blast.

Stanekzai further added that the blast took place due to a magnetic bomb which was planted in the vehicle of the Afghan army officers.

The British War On Afghanistan 1842: Part 2 “Not One Benefit, Political Or Military, Has Been Acquired With This War” “A War Carried On With A Strange Mixture Of Rashness And Timidity; Brought To A Close After Suffering And Disaster” “Our Eventual Evacuation Of The Country Resembled The Retreat Of An Army Defeated” “The Closer I Looked, The More The West’s First Disastrous Entanglement In Afghanistan Seemed To Contain Distinct Echoes Of The Neocolonial Adventures Of Our Own Day” The parallels between the two invasions I came to realise were not just anecdotal, they were substantive.

The same tribal rivalries and the same battles were continuing to be fought out in the same places 170 years later under the guise of new flags, new ideologies and new political puppeteers. The same cities were garrisoned by foreign troops speaking the same languages, and were being attacked from the same rings of hills and the same high passes.

More excerpts from a magnificent book; RETURN of a KING The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839—42

By William Dalrymple, ALFRED A. KNOPF; NEW YORK 2013

**********************************************************************

In 1843, shortly after his return from the slaughterhouse of the First Anglo-Afghan War, the army chaplain in Jalalabad, the Rev. G. R. Gleig, wrote a memoir about the disastrous expedition of which he was one of the lucky survivors.

It was, he wrote, “a war begun for no wise purpose, carried on with a strange mixture of rashness and timidity; brought to a close after suffering and disaster, without much glory attached either to the government which directed, or the great body of troops which waged it. Not one benefit, political or military, has been acquired with this war. Our eventual evacuation of the country resembled the retreat of an army defeated.”

William Barnes Wollen’s celebrated painting of the Last Stand of the 44th Foot—a group of ragged but doggedly determined soldiers on the hilltop of Gandamak standing encircled behind a thin line of bayonets, as the Pashtun tribesmen close in — became one of the era’s most famous images, along with Remnants of an Army, Lady Butler’s oil of the alleged last survivor, Dr. Brydon, arriving before the walls of Jalalabad on his collapsing nag.

It was just as the latest western invasion of Afghanistan was beginning to turn sour in the winter of 2006 that I had the idea of writing a new history of Britain’s first failed attempt at controlling Afghanistan.

After an easy conquest and the successful installation of a pro- western puppet ruler, the regime was facing increasingly widespread resistance.

History was beginning to repeat itself.

In the course of the initial research I visited many of the places associated with the war. The Last Stand of the 44th Regiment at Gundamuck, 1842. William Barnes Wollen

On my first day in Afghanistan I drove through the Shomali Plain to see the remains of Eldred Pottinger’s barracks at Charikar, which now lie a short distance from the U.S. Air Force base at Bagram.

In Herat I paid my respects at the grave of Dost Mohammad Khan, at the Sufi shrine of Gazur Gah. In Jalalabad I sat by the Kabul River and ate the same delicious shir maheh river fish, grilled on charcoal, which 170 years earlier had sustained the British troops besieged there and which had been particularly popular with “Fighting Bob” Sale.

On my arrival in Kandahar, the car sent to pick me up from the airport received a sniper shot through its back window as it neared the perimeter; later I stood at one of Henry Rawlinson’s favourite spots, the shrine of Baba Wali on the edge of town, and saw an lED blow up a U.S. patrol as it crossed the Arghandab River, then as now the frontier between the occupied zone and the area controlled by the Afghan resistance.

In Kabul I managed to get permission to visit the Bala Hisar, once Shah Shuja’s citadel, now the headquarters of the Afghan Army’s intelligence corps, where reports from the front line are evaluated amid a litter of spiked British cannon from 1842 and upturned Soviet T-72 tanks from the 19805.

“The Same Tribal Rivalries And The Same Battles Were Continuing To Be Fought Out In The Same Places 170 Years Later Under The Guise Of New Flags, New Ideologies And New Political Puppeteers”

The closer I looked, the more the west’s first disastrous entanglement in Afghanistan seemed to contain distinct echoes of the neocolonial adventures of our own day.

For the war of 1839 was waged on the basis of doctored intelligence about a virtually non-existent threat: information about a single Russian envoy to Kabul was exaggerated and manipulated by a group of ambitious and ideologically driven hawks to create a scare—in this case, about a phantom Russian invasion.

As John MacNeill, the Russophobe British ambassador, wrote from Teheran in 1838: “we should declare that he who is not with us is against us . . . We must secure Afghanistan.” Thus was brought about an unnecessary, expensive and entirely avoidable war.

The Remnants of an Army. Elizabeth Lady Butler

The parallels between the two invasions I came to realise were not just anecdotal, they were substantive.

The same tribal rivalries and the same battles were continuing to be fought out in the same places 170 years later under the guise of new flags, new ideologies and new political puppeteers.

The same cities were garrisoned by foreign troops speaking the same languages, and were being attacked from the same rings of hills and the same high passes.

In both cases, the invaders thought they could walk in, perform regime change, and be out in a couple of years.

In both cases they were unable to prevent themselves getting sucked into a much wider conflict.

Just as the British inability to cope with the rising of 1841 was a product not just of the leadership failures within the British camp, but also of the breakdown of the strategic relationship between Macnaughton and Shah Shuja, so the uneasy relationship of the ISAF leadership with President Karzai has been a crucial factor in the failure of the latest imbroglio. Here the U.S. special envoy Richard Hoibrooke to some extent played the role of Macnaughton.

When I visited Kabul in 2010, the then British Special Representative, Sir Sherard Cowper-Coles, described Holbrooke as “a bull who brought his own china shop wherever he went “— a description that would have served perfectly to sum up Macnaughton’s style I74 years previously.

Sherard’s analysis of the failure of the current occupation in his memoirs, Cables from Kabul, reads astonishingly like an analysis of that of Auckland and Macnaghten: “Getting in without having any real idea of how to get out; almost *wilful misdiagnosis of the nature of the challenges; continually changing objectives, and no coherent or consistent plan; mission creep on a heroic scale; disunity of political and military command, also on a heroic scale; diversion of attention and resources (to Iraq in the current case, to the Opium Wars then) at a critical stage of the adventure; poor choice of local allies; weak political leadership.”

Then as now, the poverty of Afghanistan has meant that it has been impossible to tax the Afghans into financing their own occupation.

Instead, the cost of policing such inaccessible territory has exhausted the occupier’s resources.

Today the U.S. is spending more than $100 billion a year in Afghanistan: it costs more to keep Marine battalions in two districts of Helmand than the U.S. is providing to the entire nation of Egypt in military and development assistance.

In both cases the decision to withdraw troops has turned on factors with little relevance to Afghanistan, namely the state of the economy and the vagaries of politics back home.

As I pursued my research, it was fascinating to see how the same moral issues that are chewed over in the editorial columns today were discussed at equal length in the correspondence of the First Afghan War: what are the ethical responsibilities of an occupying power?

Should you try to “promote the interests of humanity,” as one British official put it in 1840, and champion social and gender reform, banning traditions like the stoning to death of adulterous women; or should you just concentrate on ruling the country without rocking the boat?

Do you intervene if your allies start boiling or roasting their enemies alive? Do you attempt to introduce western political systems?

As the spymaster Sir Claude Wade warned on the eve of the 1839 invasion, “There is nothing more to be dreaded or guarded against, I think, than the overweening confidence with which we are too often accustomed to regard the excellence of our own institutions, and the anxiety that we display to introduce them in new and untried soils. Such interference will always lead to acrimonious disputes, if not to a violent reaction.” For the westerners in Afghanistan today, the disaster of the First Afghan War provides an uneasy precedent: it is no accident that the favourite watering hole of foreign correspondents in Kabul is called the Gandamak Lodge, or that one of the principal British bases in southern Afghanistan is named Camp Souter after the only survivor of the last stand of the 44th Foot.

For the Afghans themselves, in contrast, the British defeat of 1842 has become a symbol of liberation from foreign invasion, and of the determination of Afghans to refuse to be ruled ever again by any foreign power.

The diplomatic quarter of Kabul is after all still named after Wazir Akbar Khan, who in nationalist Barakzai propaganda is now remembered as the leading Afghan freedom fighter of 1841—2.

“We In The West May Have Forgotten The Details Of This History That Did So Much To Mould The Afghans’ Hatred Of Foreign Rule, But The Afghans Have Not”

We in the west may have forgotten the details of this history that did so much to mould the Afghans’ hatred of foreign rule, but the Afghans have not.

In particular Shah Shuja remains a symbol of quisling treachery in Afghanistan: in 2001 the Taliban asked their young men, “Do you want to be remembered as a son of Shah Shuja or as a son of Dost Mohammad?”

As he rose to power, Mullah Omar deliberately modelled himself on Dost Mohammad, and like him removed the Holy Cloak of the Prophet Mohammad from its shrine in Kandahar and wrapped himself in it, declaring himself like his model Amir al-Muminin, the Leader of the Faithful, a deliberate and direct re-enactment of the events of the First Afghan War, whose resonance was immediately understood by all Afghans.

History never repeats itself exactly, and it is true that there are some important differences between what is taking place in Afghanistan today and what took place during the 1840s.

There is no unifying figure at the centre of the resistance, recognised by all Afghans as a symbol of legitimacy and justice: Mullah Omar is no Dost Mohammad or Wazir Akbar Khan, and the tribes have not united behind him as they did in 1842.

Nevertheless, due to the continuities of the region’s topography, economy, religious aspirations and social fabric, the failures of 170 years ago do still hold important warnings for us today.

As George Lawrence wrote to the London Times just before Britain blundered into the Second Anglo-Afghan War thirty years later, “a new generation has arisen which, instead of profiting from the solemn lessons of the past, is willing and eager to embroil us in the affairs of that turbulent and unhappy country. . . Although military disasters may be avoided, an advance now, however successful in a military point of view, would not fail to turn out to be as politically useless. . .

“The disaster of the Retreat from Kabul should stand forever as a warning to the Statesmen of the future not to repeat the policies that bore such bitter fruit in 1839—42.”

SOMALIA WAR REPORTS

Insurgents Attack In Mogadishu

23 July 2014 By Maalik Som, Shabelle

Deadly battle flared up on last night between Somali National army forces and Al Shabaab militants in Mogadishu, reports said.

The fatal skirmishes erupted after fighters from Al Shabaab launched an ambush attack against Somali Government bases located SOS, Suuqa Xoolaha and ex-control junction of Bal'ad villages in Mogadishu.

The exact number of casualties on both warring side are yet to be unclear. After the fighting, Somali National army forces arrested dozens on suspicion of Al Shabaab members.

MILITARY NEWS YOUR INVITATION: Comments, arguments, articles, and letters from service men and women, and veterans, are especially welcome. Write to Box 126, 2576 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10025-5657 or email [email protected]: Name, I.D., withheld unless you request publication. Same address to unsubscribe.

“It’s Kind Of Terrifying To Be In Such An Emotionally Safe Environment And Then Suddenly Be Expelled Into An Alienated, Fractured, Empty American Society” “I Think They’re Seeing Our Society Clearly For The First Time, Because They’ve Experienced The Opposite In Combat” “Redeploying To The Dirty Water Back Home Becomes Heartbreaking. They’re Seeing The Alienation. They’re Experiencing The Loneliness” “And For Many Vets, That’s More Frightening Than Combat Ever Was”

1st Infantry Division soldier in “Korengala

June 30, 2104 By Jon R. Anderson, Army Times [Excerpts]

When Army paratrooper Sgt. Brendan O’Byrne returned from a tortured year of combat in Afghanistan’s deadly Korengal Valley, he looked into the lens of a video camera and wondered out loud whether God hated him for what he had done there.

“I’m not religious or anything, but I felt like there was hate for me, because I did ...” O’Byrne says, pausing, “... sins. I sinned. And although I would have done it the same way — everything the same exact way — I still feel this way.

“That’s the terrible thing with war. You do terrible things, then you have to live with them afterwards. But you’d do it the same way if you had to go back.” Despite those conflicting emotions, a part of O’Byrne wanted to go back.

That’s something author, filmmaker and war correspondent Sebastian Junger would hear again and again from troops returning from combat: They missed it.

In his new documentary “Korengal,” Junger explores that paradox among warfighters who have learned to hate war — but love combat.

Junger’s Oscar-nominated 2010 documentary “Restrepo” followed O’Byrne and his platoon of troops through their deployment to a remote mountaintop outpost during some of the worst fighting in Afghanistan.

“Korengal” picks up where “Restrepo” leaves off, not so much as the next chapter in the story of those troops, but as a way to delve more deeply into what they went through.

“It’s meant to be complementary to ‘Restrepo,’ ” Junger tells OFFduty. “ ‘Restrepo’ is mostly for civilians to give them a sense of the experience of combat. ‘Korengal’ is more for the soldiers themselves, to inquire more deeply into their experience and how it affected them.”

While often hated in the moment, combat deployments become a blessing of sorts, Junger says. There is a clarity of focus and purpose that comes with war that few in civilian life will ever know.

Mix that with daily doses of high adrenaline and a kind of pure loyalty among those you fight alongside, and combat is a perfect baptism into tribal brotherhood.

Many troops may not even like those they serve alongside, but there is a certainty among them that each would not hesitate to die for the other, Junger says.

But that blessing becomes a curse when they return home.

“They miss the brotherhood — that incredibly close bond between 30 guys in combat. And real intimacy. From the bunk I slept in at Restrepo I could reach my arm out and touch three other men. We were really close — physically and emotionally close.

“It’s kind of terrifying to be in such an emotionally safe environment and then suddenly be expelled into an alienated, fractured, empty American society,” Junger says.

“We have the highest rates of suicide, depression and child abuse — and now mass killings — ever in human history. It’s crazy. And that’s the society these guys are coming back to.”

Like a fish who has known only dirty water, war provides an ironic clarity of what life could be like. But redeploying to the dirty water back home becomes heartbreaking.

“I think they’re seeing our society clearly for the first time, because they’ve experienced the opposite in combat. They’re seeing the alienation. They’re experiencing the loneliness.” And for many vets, that’s more frightening than combat ever was.

“Feeling alone and alienated — that’s scarier than bullets. They know how to deal with bullets, and in combat they’re dealing with bullets together. But now they’re dealing with their loneliness, by definition, alone. And that’s way scarier,” Junger says.

While helping troops wrestling with post-traumatic stress is important, he goes on, “It makes me think, at the end of the day, who really has the problem, us or them? Who really needs to be healed? I’m not talking about healing from the trauma of, say, seeing someone’s leg blown off.

“That’s a whole other thing. I’m talking about the sense of alienation when they come home.”

Most Israeli soldiers returning from combat don’t have that problem, he points out.

“My guess is it’s because everyone serves in the military and they come back to a society that’s coherent, in a defensive posture, and everyone is involved. So there’s no readjustment. Most ancient tribal societies were the same way.”

FORWARD OBSERVATIONS “At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. Oh had I the ability, and could reach the nation’s ear, I would, pour out a fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern rebuke.

“For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder.

“We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake.”

“The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppose.”

Frederick Douglass, 1852

It would be a fundamental mistake to suppose that the struggle for democracy can divert the proletariat from the socialist revolution, or obscure, or overshadow it, etc. On the contrary, just as socialism cannot be victorious unless it introduces complete democracy, so the proletariat will be unable to prepare for victory over the bourgeoisie unless it wages a many-sided, consistent, and revolutionary struggle for democracy.” -- V. I. Lenin, Collected Works, 4th English Edition; Vol. 22

“Of All Persons, Therefore, The Productive Worker Has Least Command Over The Services Of Unproductive Workers, Although He Has Most To Pay For The Involuntary Services (The State And Taxes)” “The Artisan Or Peasant Who Produces With His Own Means Of Production Will Either Gradually Be Transformed Into A Small Capitalist Who Also Exploits The Labour Of Others, Or He Will Suffer The Loss Of His Means Of Production And Be Transformed Into A Wage Worker” “It Can Therefore Be Assumed That The Whole World Of Commodities, All Spheres Of Material Production — The Production Of Material Wealth — Are Subordinated To The Capitalist Mode Of Production”

From Karl Marx, Theories Of Surplus Value; International Publishers; New York, 1952

The performance of certain services, or the use values resulting from certain activities or labours, are embodied in commodities; others on the contrary leave no tangible results separate from the persons themselves; or, their result is not a vendible commodity.

For example, the service rendered to me by a singer satisfies my aesthetic need; but what I enjoy exists only in an action inseparable from the singer himself; and as soon as his labour, the singing, comes to an end my enjoyment is also over; I enjoy the activity itself — its reverberation on my ear.

These services themselves, like the commodities which I buy, may be necessary or may only seem necessary — for example the service of a soldier, a doctor or a lawyer; or they may be services which only yield enjoyment.

But this makes no difference to their economic character.

If I am in good health and do not need a doctor, or have the good luck not to be involved in a lawsuit, I avoid paying out money for medical or legal services as I do the plague.

The services may also be forced on me: the services of officials, etc.

If I buy the service of a teacher not to develop my faculties but to acquire skills with which I can earn money — or when others buy this teacher for me — and if I really learn something, which in itself is quite independent of the payment for the service — these costs of education, like the costs of my maintenance, belong to the costs of production of my labour power.

But the special usefulness of this service does not alter the economic relation; it is not a relation in which I transform money into capital, or whereby the supplier of the service, the teacher, transforms me into his capitalist, his master.

Consequently it also does not affect the economic character of this relation whether the doctor cures me or the teacher makes a success of teaching me or the lawyer wins my lawsuit.

What is paid for is the performance of the service as such, and by its very nature the result cannot be guaranteed by those who render the service.

A great part of services belongs to the costs of consumption of commodities, such as those of a cook, maid, etc. It is characteristic of all unproductive labours that they are at my disposal — as is the case in the purchase of all other commodities for consumption — in the same proportion as that in which I exploit productive workers.

Of all persons, therefore, the productive worker has least command over the services of unproductive workers, although he has most to pay for the involuntary services (the State and taxes).

Vice versa, however, my power to employ productive workers does not at all increase in proportion to the extent that I employ unproductive workers, but on the contrary falls in the same proportion.

Productive workers may, in relation to me, be unproductive workers.

For example, if I have my house re-papered, and the paper-hangers are wage workers of an employer who sells me the job, it is just the same for me as if I had bought a house already papered: I would have expended money for a commodity for my consumption; but for the employer who gets these workers to hang the paper they are productive workers, for they produce surplus value for him.

What then is the position of independent handicraftsmen or peasants who employ no workers and therefore do not produce as capitalists?

Either, as always in the case of the peasant (but not for example of a gardener whom I get to come to my house), they are commodity producers and I buy the commodity from them — in which case it makes no difference for example that the handicraftsman supplies it to order or the peasant brings to market what he can.

In this relationship they meet me as sellers of commodities, not as sellers of labour, and this relation has therefore nothing at all to do with the exchange of capital, and therefore also nothing to do with the distinction between productive and unproductive labour, which is based purely on whether the labour is exchanged with money as money or with money as capital.

They therefore belong neither to the category of productive nor to that of unproductive workers, although they are producers of commodities. But their production does not fall under the capitalist mode of production.

It is possible that these producers working with their own means of production not only reproduce their labour power but create surplus value, since their position makes it possible for them to appropriate their own surplus labour or a part of it (as one part is taken from them in the form of taxes, etc.).

And here we come up against a peculiarity that is characteristic of a society in which one definite mode of production predominates, although all productive relations have not yet been subordinated to it.

In feudal society, for example, as we can best observe in England because here the system of feudalism was introduced ready made from Normandy and its form was impressed on what was in many respects a different social foundation — even productive relations which were far removed from the nature of feudalism were given a feudal form; for example, simple money relations in which there was no trace of mutual personal service as between suzerain and vassal, for instance the fiction that the small peasant held his property as a fief.

In just the same way in the capitalist mode of production the independent peasant or handicraftsman is sundered into two persons.

As owner of the means of production he is capitalist, as worker he is his own wage worker.

As capitalist, he therefore pays himself his wages and draws his profit from his capital; that is to say, he exploits himself as wage worker and pays himself with the surplus value, the tribute that labour owes to capital.

Perhaps he also pays himself a third part as landowner (rent), in the same way, as we shall see later, that the industrial capitalist who works with his own capital pays himself interest and regards this as something which he owes to himself not as an industrial capitalist, but qua capitalist pure and simple.

The social character of the means of production in capitalist production — the fact that they express a definite productive relation — has so grown together with, and in the mode of thought of bourgeois society is so inseparable from, the material existence of these means of production as means of production, that the same definition (definite category) is applied even where the relation is the very opposite.

The means of production become capital only in so far as they have become an independent power confronting labour.

In the case mentioned the producer — the worker — is the possessor, owner, of his means of production.

They are therefore not capital, any more than in relation to them he is a wage worker.

Nevertheless they are thought of as capital, and he himself is split in two, so that as capitalist he employs himself as wage worker

In fact this way of presenting it, however irrational it may seem at first sight, is nevertheless correct in so far as the producer in such a case actually creates his own surplus value (assuming that he sells his commodity at its value), or the whole product materialises only his own labour.

That he is able to appropriate to himself the whole product of his own labour, and that the excess of the value of his product over the average price of his day’s labour is not appropriated by someone else, he owes however not to his labour — which does not distinguish him from other workers — but to his ownership of the means of production.

It is therefore only through his ownership of these that he takes possession of his own surplus labour, and thus arises his relation, as his own capitalist, to himself as wage worker.

The separation between the two is the normal relation in this society. Where therefore it does not in fact exist, it is presumed, and, as shown above, up to a point with justice; for (as distinct for example from conditions in Ancient Rome or Norway or in the North-West of the United States) in this society the unity appears as accidental, the separation as normal, and consequently the separation is maintained as the relation, even when one person unites the different functions.

Here emerges in a very striking way the fact that the capitalist as such is only a function of capital, the worker a function of labour power.

For it is also a law that economic development divides out functions among different persons, and the artisan or peasant who produces with his own means of production will either gradually be transformed into a small capitalist who also exploits the labour of others, or he will suffer the loss of his means of production (this may happen to begin with although he remains their nominal owner, as in a mortgage) and be transformed into a wage worker.

This is the tendency in the form of society in which the capitalist mode of production predominates.

In examining the essential relations of capitalist production it can therefore be assumed that the whole world of commodities, all spheres of material production — the production of material wealth — are subordinated (formally or really) to the capitalist mode of production (since this is being continuously approximated to, is in principle the goal of capitalist production, and only if this is realised will the productive power of labour be developed to its highest point).

On this premise, which expresses the goal (limit), and which therefore is constantly coming closer to exact truth, all workers engaged in the production of commodities are wage workers, and the means of production in all these spheres confront them as capital.

It can then be said to be a characteristic of productive workers, that is, of capital- producing workers, that their labour is realised in commodities, in material wealth.

MILITARY RESISTANCE BY EMAIL If you wish to receive Military Resistance immediately and directly, send request to [email protected]. There is no subscription charge. Same address to unsubscribe.

Military Resistance In PDF Format? If you prefer PDF to Word format, email: [email protected] DANGER: CAPITALISTS AT WORK

OCCUPATION PALESTINE AP Reporter In Gaza Needs Another Term For ‘Blood-Soaked’

Jul 23, 2014 The Onion

GAZA CITY— Saying that he doesn’t want to use the same phrasing yet again in his latest article, Associated Press journalist Marcus Lambert, who has been stationed in the Gaza Strip since the beginning of this month’s most recent outbreak of Israeli- Palestinian violence, told reporters Wednesday that he is having trouble finding another term for “blood-soaked.”

“I’m trying to find a way to describe the scene after today’s airstrikes, but I’ve used ‘blood-soaked’ two times already,” Lambert said while writing his latest update, adding that he had also used up the phrases “blood-drenched,” “bloodstained,” and “saturated with blood” in the same dispatch.

“Blood-spattered is close, but it’s not quite right. The problem is that there are only so many expressions to describe this kind of thing. And you can’t just say ‘a whole lot of blood’ or ‘more blood than ever before’—that’s not AP style.

Maybe I could describe the blast site as ‘crimsoned?’ Man, this is a tough one.”

At press time, following heavy shelling of Gaza’s Bani Suhaila region, Lambert was also intently seeking synonyms for “bombed-out,” “wailing,” and “orphan.”

To check out what life is like under a murderous military occupation commanded by foreign terrorists, go to: http://www.maannews.net/eng/Default.aspx and http://www.palestinemonitor.org/list.php?id=ej898ra7yff0ukmf16 The occupied nation is Palestine. The foreign terrorists call themselves “Israeli.” DANGER: POLITICIANS AT WORK

Fleeing Iraqis Relieved That Cheney Has No Regrets About War Photograph by Emrah Yorulmaz/Anadolu/Getty.

July 16, 2004 The Borowtiz Report

BAGHDAD — Just days after former Vice-President Dick Cheney said that he had no regrets about the invasion of Iraq, people fleeing their homes across that war-torn nation expressed tremendous relief that he was at peace with his decision.

As news spread that Cheney would not change a thing about the 2003 invasion, Iraqis driven out of their villages and towns by marauding terrorists called the former Vice- President’s words well-timed and soothing.

Sabah al-Alousi, who fled Mosul when ISIS militants overran it last month, said that Cheney’s confident pronouncement about the invasion of Iraq “is the first good news I’ve heard in a long time.”

“As I’ve fled from town to town, looking for a place where I might not be suddenly slain for no reason, the one thought that kept nagging me was, ‘How does Dick Cheney feel about all of this?’” he said. “I can’t tell you what a relief it is to know he isn’t losing any sleep.”

The Iraqi man said that he had been concerned that Cheney might harbor regrets about Iraq, such as the trillions of dollars spent, thousands of lives lost, W.M.D.s not found, and international disgrace of Abu Ghraib, but thanks to the former Vice-President’s recent statements, “I now see that I was worried about nothing.”

“Iraq is a scary place right now,” al-Alousi said. “The country could be broken into pieces, or become a part of an Islamic caliphate, or be the scene of unspeakable sectarian violence for years to come.

“But somehow, knowing that Dick Cheney would do it all over again if he could makes everything a little better.”

DO YOU HAVE A FRIEND OR RELATIVE IN MILITARY SERVICE? Forward Military Resistance along, or send us the address if you wish and we’ll send it regularly.

Whether at a base in the USA or stationed outside the Continental United States, this is extra important for your service friend, too often cut off from access to encouraging news of growing resistance to the war and economic injustice, inside the armed services and at home.

Send email requests to address up top or write to: The Military Resistance, Box 126, 2576 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10025-5657. Vietnam GI: Reprints Available Edited by Vietnam Veteran Jeff Sharlet from 1968 until his death, this newspaper rocked the world, attracting attention even from Time Magazine, and extremely hostile attention from the chain of command.

The pages and pages of letters in the paper from troops in Vietnam condemning the war are lost to history, but you can find them here.

Military Resistance has copied complete sets of Vietnam GI. The originals were a bit rough, but every page is there. Over 100 pages, full 11x17 size.

Free on request to active duty members of the armed forces.

Cost for others: $15 if picked up in New York City. For mailing inside USA add $5 for bubble bag and postage. For outside USA, include extra for mailing 2.5 pounds to wherever you are.

Checks, money orders payable to: The Military Project

Orders to: Military Resistance Box 126 2576 Broadway New York, N.Y. 10025-5657

All proceeds are used for projects giving aid and comfort to members of the armed forces organizing to resist today’s Imperial wars. Military Resistance Looks Even Better Printed Out Military Resistance/GI Special are archived at website http://www.militaryproject.org .

Issues are also posted at: http://www.uruknet.info/

Military Resistance distributes and posts to our website copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in an effort to advance understanding of the invasion and occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan. We believe this constitutes a “fair use” of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law since it is being distributed without charge or profit for educational purposes to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for educational purposes, in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. Military Resistance has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of these articles nor is Military Resistance endorsed or sponsored by the originators. This attributed work is provided a non-profit basis to facilitate understanding, research, education, and the advancement of human rights and social justice. Go to: law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml for more information. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

If printed out, a copy of this newsletter is your personal property and cannot legally be confiscated from you. “Possession of unauthorized material may not be prohibited.” DoD Directive 1325.6 Section 3.5.1.2.