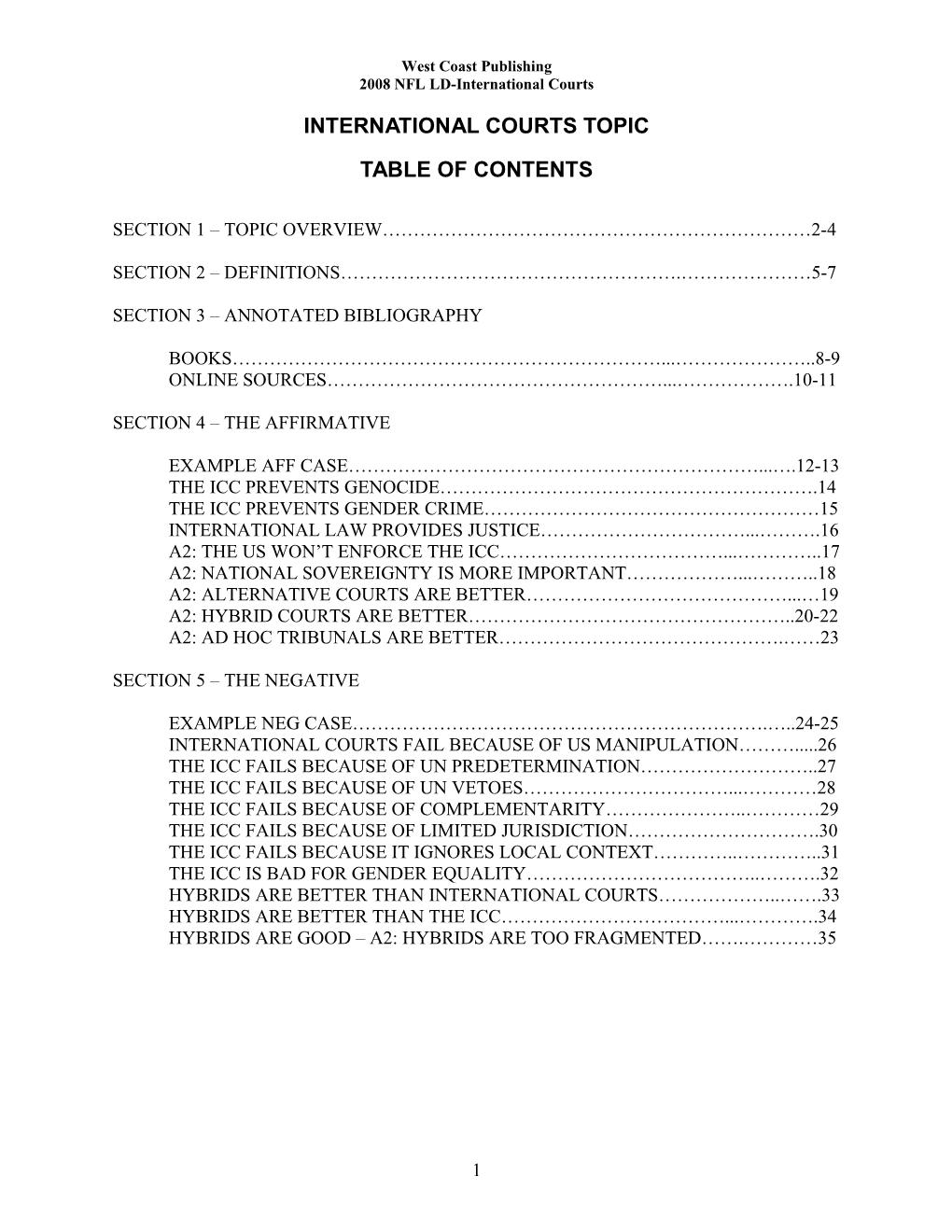

West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

INTERNATIONAL COURTS TOPIC

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SECTION 1 – TOPIC OVERVIEW……………………………………………………………2-4

SECTION 2 – DEFINITIONS……………………………………………….…………………5-7

SECTION 3 – ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS……………………………………………………………...…………………..8-9 ONLINE SOURCES………………………………………………...……………….10-11

SECTION 4 – THE AFFIRMATIVE

EXAMPLE AFF CASE…………………………………………………………...….12-13 THE ICC PREVENTS GENOCIDE…………………………………………………….14 THE ICC PREVENTS GENDER CRIME………………………………………………15 INTERNATIONAL LAW PROVIDES JUSTICE……………………………...……….16 A2: THE US WON’T ENFORCE THE ICC………………………………...…………..17 A2: NATIONAL SOVEREIGNTY IS MORE IMPORTANT………………...………..18 A2: ALTERNATIVE COURTS ARE BETTER……………………………………...…19 A2: HYBRID COURTS ARE BETTER……………………………………………..20-22 A2: AD HOC TRIBUNALS ARE BETTER……………………………………….……23

SECTION 5 – THE NEGATIVE

EXAMPLE NEG CASE………………………………………………………….…..24-25 INTERNATIONAL COURTS FAIL BECAUSE OF US MANIPULATION……….....26 THE ICC FAILS BECAUSE OF UN PREDETERMINATION………………………..27 THE ICC FAILS BECAUSE OF UN VETOES……………………………...…………28 THE ICC FAILS BECAUSE OF COMPLEMENTARITY…………………..…………29 THE ICC FAILS BECAUSE OF LIMITED JURISDICTION………………………….30 THE ICC FAILS BECAUSE IT IGNORES LOCAL CONTEXT…………..…………..31 THE ICC IS BAD FOR GENDER EQUALITY………………………………..……….32 HYBRIDS ARE BETTER THAN INTERNATIONAL COURTS………………..…….33 HYBRIDS ARE BETTER THAN THE ICC………………………………...………….34 HYBRIDS ARE GOOD – A2: HYBRIDS ARE TOO FRAGMENTED…….…………35

1 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

SECTION 1 – TOPIC ANALYSIS

Resolved: The United States ought to submit to the jurisdiction of an international court designed to prosecute crimes against humanity.

Eric Chalfant Whitman College

INTRODUCTION This topic appears to raise two significant questions concerning the role of the United States in international justice. First, the resolution begs the question of whether and to what extent the US would benefit an international justice system by submitting to its jurisdiction. Second, the resolution asks whether and to what extend the US itself would benefit from making human rights decisions based on international norms rather than potentially self-motivated standards. As Jean Galbraith, a JD candidate at UC Berkeley’s School of Law, put it, “A principle is at stake. This principle is one of national sovereignty at all costs over any binding form of international accountability.” (21 Berkeley J. Int'l L. 683) For this reason, the topic appears to raise a number of secondary questions concerning the role of self-motivation vs. submission to broader authority. Should the United States defend its own standards of human rights or is it better to attempt to fashion international standards to which the world at large should adhere? To some extent, this topic can be seen to ask the broader question of whether standards of justice should be universal or specific to individual nations, or perhaps whether we must develop standards of justice that somehow balance the universal and the local.

INTERNATIONAL COURTS At the outset of this topic discussion, it is important to note that the resolution does not refer to a specific international court. Thus, there is potential for debaters to fashion cases specific to obscure and relatively small international courts, despite the fact that the International Criminal Court (ICC) is the single largest and widely recognized international court in the world. While it may be possible to focus this topic on another criminal court, it is likely that the topic writers had the ICC in mind, since it is also the only international court that has actively pursued US involvement and that the US has actively considered joining. But what is an international court? It will probably be a hard phrase to find in a dictionary. Most definitions of the phrase are contextual, coming up in discussions of the various kinds of national and international justice systems. In the last 20 years, the international ad hoc tribunal has been used to establish temporary courts designed to resolve a specific humanitarian crisis. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), was created by the United Nations in 1993 to prosecute serious criminals during the wars in the former Yugoslavia. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was created by the United Nations in 1994 to prosecute individuals responsible for the Rwandan genocide. These tribunals, however, are geared only toward those specific crises. There are, however, international judiciaries with a wider jurisdiction. The International Court of Justice, the official court of the United Nations and commonly called the World Court, has jurisdiction over UN Nations that wish to settle legal disputes. Submission to this court’s jurisdiction is not mandatory, and the US has rejected compulsory jurisdiction, cooperating with the World Court on a case-by-case basis. It is unlikely that the topic was geared toward this international court, as the US is already technically a member. The international court that the United States has vehemently refused to join is the International Criminal Court, located in the Hague, Netherlands. To understand the International Criminal Court, which claims jurisdiction over all participatory nations, we must also understand the Court’s history. If there is a reliable definition of “international court,” it will be found in the structure of the International Criminal Court.

THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT The international court system designed to prosecute crimes against humanity has a short and controversially ineffective history. The United Nations has been primarily responsible for the prosecution of crimes against humanity since it was chartered in 1948. The International Criminal Court was organized in 2002 in the Hague (Netherlands) explicitly to deal with matters relating to crimes against humanity, but has yet to complete its first trial, of a man named Thomas Lubanga, and progress relating to the Sudanese genocide in Darfur has been slow. The ICC has little executive power. Cases are referred by the United Nations, and there has not been a new trial since March 2005. Additionally, the ICC cannot arrest wanted individuals, but can only issue warrants for arrest and then rely on nations to arrest and offer suspects. Furthermore, the ICC can exercise jurisdiction only when national courts are unwilling or unable to prosecute crimes against humanity domestically. Thus, it has been

2 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts difficult to try powerful domestic actors, since those actors must essentially turn themselves in to the criminal court. Also, the ICC can only prosecute crimes committed on or after its date of creation, July 1, 2002. Finally, the ICC only claims jurisdiction over its 106 member-states. 40 additional countries have signed but not ratified the Rome Statute, and a number of powerful states including China and the United States have refused to join the court. (President Clinton signed the Rome Statute in 2000 without submitting it to the Senate for ratification. In 2002, President Bush unsigned the statute.) Initially, it was proposed that the ICC be given universal jurisdiction. However, opposition from the United States was largely responsible for the limitation on the ICC’s jurisdictional rights. To date, the ICC has only opened four investigations and issued public arrest warrants for twelve people, six of which remain free. The unsuccessful trial of Lubanga due to suspicious actions by Lubanga’s prosecutor has opened the ICC to allegations of ineffectiveness by non-members such as the United States. It is important to note that crimes against humanity are only one of four groups of crimes governed by the International Criminal Court, including war crimes, genocide, and the crime of aggression, which has yet to be defined or discussed in trial. Today, the International Criminal Court is the only body given comprehensive jurisdiction over international crime.

UNITED STATES OPPOSITION TO THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT The United States has mostly criticized the ICC because it reduces US national sovereignty. Furthermore, George W. Bush has been particularly vocal in criticizing vague and broad jurisdictional claims made by the ICC. Members of his cabinet have claimed that giving the ICC jurisdiction over international prosecution could lead to politically-motivated prosecutions that unfairly target the United States. In 2002, the U.S. Congress passed the American Servicemembers' Protection Act (ASPA), which contained provisions prohibiting the United States from providing military aid to countries which had ratified the treaty establishing the court, with exceptions for NATO members, major non-NATO allies, and countries which agreed with the United States not to hand over US nationals to the court. Many of these limits on military assistance have been repealed. Additionally, the ASPA contained provisions prohibiting US cooperation with the ICC and permitting the President to authorize the use of force to free any US military personnel held by the court. Thus, many opponents dubbed the ASPA the “Hague Invasion Act.” The act was eventually modified to permit US cooperation with the ICC if it aided in United States efforts to deal with foreign enemies. The International Criminal Court is distinctive in that it’s definitions of human rights and legal norms are universal. The ICC will allow national judiciaries to attempt to genuinely prosecute individuals who commit crimes against humanity, but its own judiciary is entirely separate and authoritative. There are other possibilities for the relationship between international, national, and even local judiciaries, however. Hybrid tribunals or hybrid courts attempt to blur the lines between international and national judiciaries and combine the best elements of both. Allowing a hybrid court to have the strength of an international authority and the unique perspective of local judiciaries and populations. The Special Tribunal for Lebanon and the Special Tribunal for Sierra Leone were both hybrid courts. The Special Tribunal for Lebanon incorporated judges from both international and Lebanese chambers and incorporated Lebanese law into international standards. These hybrid courts may be an alternative to international courts, or they may be a subset of international courts. Etelle Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, writes: Hybrids blend the international and the domestic with legal and organizational innovations that constitute important divergences from international ad hoc tribunals. In some cases they coexist with the local judiciary, operating in parallel, while in others, they have been grafted onto the local judicial system. But in all cases their nature is mixed. Usually, they are composed of international and local staff with foreign judges sitting alongside their domestic counterparts to try cases prosecuted and defended by teams of both local and foreign lawyers. Domestic law--reformed to include international standards--is typically applied alongside international law. Ultimately, hybrid criminal bodies form a family of their own, apart from other judicial entities. (23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347) Many debates on this topic may come down to a comparison of the effectiveness of international courts versus hybrid courts or ad-hoc tribunals. International courts have the advantage of powerful enforcement and community consensus, but lack the ability to flexibly interact with specific populations, while hybrid courts or ad hoc tribunals may have more to offer in terms of supporting indigenous judiciaries and sustainable international justice, but may lack the necessary power of authority to compel changes in behavior. In much of the literature on this question, there is a comparison to long-term versus short-term goals. International courts may be designed to immediately resolve humanitarian crises, with less attention paid to supporting sub-international justice, while hybrids and ad hoc tribunals may be designed to foster long term growth in indigenous judiciaries to prevent future crises before they happen. Another apt analogy is “give a person a fish and they will eat for a day” versus “teach a person to fish and they will eat forever.”

3 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY One of the most significant terms in this topic appears to be “crimes against humanity.” The phrase was first used in an international declaration on May 24, 1915, when the Allied Powers Britain, France, and Russia issued a joint statement condemning a series of “massacres” carried out by the Ottoman Government on civilian populations. According to the International Criminal Court, the most widely-known international court, crimes against humanity are defined primarily by the relationship between the actor committing the crime and the victim(s) of the crime. “An international criminal justice offence; the perpetration of acts of war upon a civilian, non-soldier population.” This includes murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation or forcible transfer of a population, imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law, torture, rape and other sexual violence, and persecution against a target population. You can see an expanded definition at Duhaime.org’s legal dictionary. The Online Business Dictionary clarifies that crimes against humanity, distinct from war-crimes, can be committed “before, during, or after a conflict or war.” (BusinessDictionary.com) Merriam-Webster, on the other hand, places emphasis on the grounds for the commitment of such crimes. A crime against humanity is “directed especially against an entire population or part of a population on specious grounds and without regard to individual guilt or responsibility even on such grounds.” (Merriam-Webster’s Online Dictionary, 2008) Presumably, crimes against humanity are often understood to be necessary atrocities in the pursuit of a broader objective. For example, the infringements on civil liberties contained in the USA Patriot Act could be argued to be crimes against humanity, despite claims that such infringements are necessary in the war on terrorism, which is more important than the civil liberties of civilians. In a similar vein, the Random House dictionary places emphasis on the innocence of the target population, defining a crime against humanity as “a crime or series of crimes, such as genocide, directed against a large group because of race, religion, country of origin, or other reason unconnected with any individual’s responsibility for having committed a criminal act.” (Random House Online Dictionary, 2008) It is also significant to note that there is a distinction between isolated infringements on human rights and crimes against humanity. According to the Rome Statue Explanatory Memorandum, which provides for the International Criminal Court to have jurisdiction over genocide, crimes against humanity, and war-crimes, crimes against humanity “are particularly odious offences in that they constitute a serious attack on human dignity or grave humiliation or a degradation of one or more human beings. They are not isolated or sporadic events, but are part either of a government policy (although the perpetrators need not identify themselves with this policy) or of a wide practice of atrocities tolerated or condoned by a government or a de facto authority. However, murder, extermination, torture, rape, political, racial, or religious persecution and other inhumane acts reach the threshold of crimes against humanity only if they are part of a widespread or systematic practice. Isolated inhumane acts of this nature may constitute grave infringements of human rights, or depending on the circumstances, war crimes, but may fall short of falling into the category of crimes under discussion.” Thus, the nation-wide civil-liberty curtailments in the USA Patriot Act could be argued to be crimes against humanity, but select detentions of enemy combatants or terrorist suspects are presumably not indiscriminate enough to qualify as crimes against humanity. Finally, it is important to note that the international classification “crimes against humanity” does not take into account domestic criminal law, such that an odious act may not necessarily violate the laws of the government committing the act, but need only violate international standards. According to the London Charter of the International Military Tribunal, set up for the Nuremberg trials, acts can be considered crimes against humanity, “whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated.” (http://www.abanet.org/irr/hr/spring00humanrights/gifford.html)

CONCLUSION

Consider the questions at the pivot of this topic and devise generic strategies upon which we can build. Is it more important for the United States to be free to make its own decisions about what is legal than it is for an international court to gain the support of a world leader as powerful as the United States? The affirmative would want to claim that strengthening the ICC is priority one, while the negative would want to claim that such infringements on United States sovereignty would destroy our ability to act decisively in guaranteeing national security. Is joining an international court a good way to guarantee international justice? The affirmative would want to claim that an international court would be effective in deterring and resolving humanitarian crises, while the negative would want to claim that to lend our support for an international court would destroy more successful alternative options like hybrid courts.

4 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

These questions are two excellent starting points for more exploration concerning international justice. There is ample room for creative argumentation on both sides of the topic, so don’t be afraid to explore the literature in the annotated bibliography; this topic is large enough to foster virtually any kind of education you desire.

5 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

SECTION 2 – DEFINITIONS

Ought – The word “ought” can be used synonymously with “should” to indicate action. This can be used to justify reading a plan or it can simply be used to ask a question of right and wrong. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. 12 Jul. 2008.

Submit – At first glance, this word appears to mean that the US must accept the authority of an international court over national laws and sovereignty. However, there is room for flexibility. For example, Princeton Wordnet defines submit as “accept as inevitable,” which has different legal implications. Obscure definitions of “submit” could be used to sidestep the question of jurisdiction and instead focus the debate on US acceptance of the existence of international courts without accepting their authority. WordNet® 3.0. Princeton University. 12 Jul. 2008.

The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. 12 Jul. 2008.

MSN Encarta Online, 2008 to accept somebody else's authority or will, especially reluctantly or under pressure

Merriam-Webster/s Online Dictionary, 2008 to yield oneself to the authority or will of another : surrender b: to permit oneself to be subjected to something

Jurisdiction – This word has a rather precise legal meaning, and there is little disagreement that jurisdiction means legal decision-making power. This word can be used as a check on obscure definitions of “submit” that attempt to avoid the debate over national vs. international sovereignty. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. 12 Jul. 2008.

6 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

International Court – this term may be distinct from international tribunals, but is defined primarily by international authority. An international court is not an agent, but is a collection of nations that are collectively responsible for enforcement. Generally, the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court are the two major international courts.

International courts require the consent of nations Judith Faucette, July 28, 2008, International Courts and International Law International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice An important aspect of these courts is that they operate based on consent. Unlike national courts, where the court has jurisdiction over individuals by virtue of national sovereignty over territory, international courts are not sovereign over any territory. Nations consent to hand jurisdiction over to the court – jurisdiction over territory, nationals, or the state itself. This is one reason why international law is considered "weak" by some detractors, as it only has as much authority as states are willing to give up.

Hybrid tribunals are not international courts because they are flexible in responding to local populations Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 However, despite ambiguities in definitions of hybrid courts, some baseline characteristics emerge. Hybrids blend the international and the domestic with legal and organizational innovations that constitute important divergences from international ad hoc tribunals. In some cases they coexist with the local judiciary, operating in parallel, while in others, they have been grafted onto the local judicial system. But in all cases their nature is mixed. Usually, they are composed of international and local staff with foreign judges sitting alongside their domestic counterparts to try cases prosecuted and defended by teams of both local and foreign lawyers. Domestic law--reformed to include international standards--is typically applied alongside international law. Ultimately, hybrid criminal bodies form a family of their own, apart from other judicial entities.

An International Court is an independent authority that can make legal decisions that supersede the national laws of participant nations Hans Kelsen, Naval War College (U.S.), 2001, Collective Security Under International Law, p.124 According to a principle of general international law, a state can exercise jurisdiction over another state through its courts, and this means jurisdiction over acts of another state, and thus make the organ of another state individually responsible for a violation of international law, only with the consent of this state. Insofar as an international court is a common court of the states which are contracting parties to the treaty by which a court or its jurisdiction is established, an international court can try individuals for having violated international law by acts of state, and this means in their capacity as organs of a state, only with the consent of this state.

Prosecute – This term also has a specific legal meaning, and it may be extremely difficult to convince a judge to accept alternative definitions. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. 12 Jul. 2008.

7 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

Crime Against Humanity – This term may be relatively flexible according to dictionaries, but has a specific term in the context of the International Criminal Court, which has an independent category for crimes against humanity. There is a limited debate as to whether genocides should be considered crimes against humanity or must be placed in a category unto themselves.

MSN Encarta Online Dictionary, 2008 atrocity: a cruel and immoral act such as torture, murder, or expulsion, committed against a large number of people

Merriam-Webster’s Online Dictionary, 2008 atrocity (as extermination or enslavement) that is directed especially against an entire population or part of a population on specious grounds and without regard to individual guilt or responsibility even on such grounds

BusinessDictionary.com, 2008 Genocide, murder, enslavement, deportation and other reprehensible acts against the civilian population committed before, during, or after a conflict or war.

The London Charter of the International Military Tribunal, set up for the Nuremberg trials Murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population . . . whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated

Random House Online Dictionary, 2008 a crime or series of crimes, such as genocide, directed against a large group because of race, religion, country of origin, or other reason unconnected with any individual’s responsibility for having committed a criminal act

8 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

SECTION 3 – ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS

Meyer, Howard. The World Court in action: judging among the nations, Lanham, Md. : Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, c2002 This book discusses the International Court of Justice, the official court of the United Nations, commonly called the World Court. The US has rejected compulsory jurisdiction, but cooperates with the World Court on a case-by-case basis.

Maogoto, Jackson Nyamuya. War crimes and realpolitik : international justice from World War I to the 21st century. c2004 This book provides a good background of the evolution of the international criminal justice system, with an emphasis on the tension between the pursuit of justice and the influences of politics in the creation of international courts.

Andrew F. Cooper et al., Editors. Enhancing global governance : towards a new diplomacy? c2002 This book argues passionately for greater interdependence and cooperation concerning international justice. It argues that despite global interdependence, powerful countries are pursuing unilateral policies that increase the risk of resentment and terrorism. It argues that the locus of international power must shift from a few imperial powers to an increased emphasis on local governance and grassroots involvement in international affairs. By ceding national authority to international courts, it will become easier for more localized bodies to become involved in international affairs by providing an arena in which sub-national bodies are on equal footing with powerful nations. The book focuses primarily on the UN.

Patrick, Stewart et al., editors. Multilateralism and U.S. foreign policy : ambivalent engagement c2002 This book has a broader subject than just international justice. It focuses on the question of why the United States is reluctant to commit to multilateral cooperation. The book provides arguments for both sides that illuminate the possible reasons why the US is ambivalent about cooperation, but concludes that the United States must de-emphasize national sovereignty for the sake of cooperation.

Drinan, Robert F. The Mobilization of Shame: A World View of Human Rights. c2001 This book tells the history of the concept of human rights and its increasing relevance in global thinking. The book has been critically acclaimed for its balanced discussion of the current state of human rights, praising the United States for being a human rights leader and simultaneously criticizing the US for refusing to join the ICC.

Riemer, Neal, Editor. Protection Against Genocide: Mission Impossible? c2000 This book is a collection of articles calling for the strengthening of global human rights institutions, with a focus on the prevention of genocide. The book argues that the current international climate provides an opportunity for substantial improvement in human rights protection, emphasizing that the largest problem today is lack of political will in supporting global institutions. It is argued that a global court in charge of determining when the use of force is appropriate in dealing with genocides is a critical component of a coherent global human rights regime.

Sewall, Sarah B., and Kaysen, Carl, Editors. The United States and the International Criminal Court : national security and international law. c2000 This book is focused almost entirely on the arguments that the United States has used to avoid joining the ICC, with emphasis on legal, historical, military, and political perspectives. The book considers both the potential risk to national security associated with signing onto the ICC as well as potential US security threats that may arise from continued national opposition to the ICC.

9 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

Frye, Alton, Project Director. Toward an International Criminal Court? : three options presented as presidential speeches. c1999 This work explores three options for US policy concerning the ICC: endorse it fully, reject it fully, or work with the ICC as a nonparty while attempting to resolve US objections to the treaty. The work takes the form of three speeches that a US president might make to the American people in announcing each hypothetical option, exploring the political implications of each.

May, Larry. Crimes Against Humanity: A Normative Account, c2005 This book focuses on the moral, political, and legal questions that arise when individuals who commit crimes against humanity are tried by international criminal tribunals. Namely, the book focuses on when breaches of national sovereignty are justified due to the nature of crimes against humanity. May attempts to determine when holding individuals liable for crimes against humanity is justified based on Hobbesian moral principles.

Robertson, Geoffrey, Crimes against humanity: the struggle for global justice. c2000. Geoffrey Robertson, a veteran lawyer in international human rights cases, lays out the history of human rights as an international concept, with a focus on the legal aspects of holding individuals responsible for crimes against humanity responsible. Robertson concludes that international courts play a pivotal role, but concedes that major world leaders will, for political reasons, remain immune from prosecution.

10 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

ONLINE SOURCES

Barrett, Matthew A., J.D. 2000, University of Georgia, Ratify or Reject: Examining the United States’ Opposition to the International Criminal Court. The Georgia of International and Comparative Law, Inc. Fall 1999, 28 Ga. J. Int'l & Comp. L. 83 This article, written as the US debated whether or not to join the ICC, discusses the legal ramification of signing onto the court. It argues that the United States could prevent the ICC from claiming jurisdiction over domestic crimes by engaging in a “genuine” investigation or prosecution of its own citizen(s). It also discusses the effect that ratification of the Rome Statute of the ICC would have on domestic due process rights.

Scheffer, David J., Senior Fellow, United States Institute of Peace, former chief negotiator for the ICC treaty regime, Staying the Course with the International Criminal Court, November 2001/February 2002, Cornell International Law Journal, 35 Cornell Int’l L.J. 47 As the former chief negotiator for the ICC treaty regime, David Scheffer argues for continued American engagement in negotiations concerning US opposition to the ICC. Furthermore, he argues that such negotiations would make cooperation with the ICC desirable, protect US interests, and make US ratification of the ICC treaty more plausible. Scheffer argues that the ICC is crucial in holding individuals in leadership positions accountable for crimes against humanity.

Kirsch, Philippe, president of the International Criminal Court, ESSAY: THE ROLE OF THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT IN ENFORCING INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW, Washington College of Law, American University, 2007, 22 Am. U. Int'l L. Rev. 539 The president of the ICC argues in this essay based on remarks given at the American University Washington College of Law that all states in a position to provide cooperation with the ICC can and must help ensure that the ICC functions properly.

Heyder, Corrina. The U.N. Security Council's Referral of the Crimes in Darfur to the International Criminal Court in Light of U.S. Opposition to the Court: Implications for the International Criminal Court's Functions and Status. Berkeley Journal of International Law, 2006, 24 Berkeley J. Int’l L. 650 This article focuses on the ICC’s case concerning the genocide in Darfur. It argues that the case would seem to deny the United States the ability to continue opposing the ICC, as the US is very clearly interested in justice in Darfur. Furthermore, it is argued that only an international body like the ICC, which gives genocide victims a global voice, can deal with international problems like genocides.

Sterio, Milena. Assistant Professor of Law, Cleveland Marshall College of Law, The Evolution of International Law, Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, Spring 2008, 31 B.C. Int’l & Comp. L. Rev. 213. This article discusses the history and development of international law, and assesses the effectiveness of international law generally in modifying state and individual behaviors.

Lavers, Troy. [PRE]DETERMINING THE CRIME OF AGGRESSION: HAS THE TIME COME TO ALLOW THE IN-TERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT ITS FREEDOM? 2008. Albany Law Review, 71 Alb. L. Rev. 299 This article discusses the referral process whereby the UN Security Council determines which cases the ICC gets to hear. It argues that the UN determination process is a substantial restriction on the potential legitimacy of the ICC, giving security council members veto power over potential cases and creates due process problems such as right to a fair trial, as the UN body has already made a determination. The article argues that the time has come for the ICC to be given the freedom to choose its own cases. Steinberg, Richard H., and Zasloff, Jonathan M., University of California at Los Angeles School of Law, Centennial Essay: Power and International Law, January 2006, American Journal of International Law, 100 A.J.I.L. 64 This article provides a history and thorough discussion of the many sides of the contemporary debate concerning the role of international law in abolishing or enhancing the role of power in international relations.

11 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

Franck, Thomas M., Board of Editors, American Journal of International Law, Centennial Essay: The power of legitimacy and the legitimacy of power: international law in an age of power disequilibrium. January 2006, 100 A.J.I.L. 88 This article analyzes the current crisis facing international law, as powerful countries like the US and alliances like NATO repeatedly flout international law in the name of national interest. The article indicates that the importance of “rational choice” and concerns about the primacy of national interest over international law are not the true differences between international law’s critics and defenders. Rather, the main difference between the two is “between a longer view of national interest and a narrower, more immediate approach to interest gratification.” The article concludes that the longer view better serves national interest by focusing on legitimacy while the shorter view focuses on power.

Wippman, David. Vice Provost for International Relations and Professor of Law at Cornell University, The Costs of International Justice. American Journal of International Law, October 2006, 100 A.J.I.L. 861 This article discusses the purely economic costs of the United States in adhering to the jurisdiction of international courts, with a focus on the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR).

12 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

SECTION 4 – THE AFFIRMATIVE

EXAMPLE AFFIRMATIVE CASE

I affirm this debate’s resolution: The United States ought to submit to the jurisdiction of an international court designed to prosecute crimes against humanity.

I will define key terms from the American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: 4th Edition. 2000. Submit means “To yield or surrender (oneself) to the will or authority of another.” Jurisdiction means “the right and power to interpret and apply the law” International Court has no definition in American Heritage, so I will define it as the International Criminal Court, since it is the largest and most widely recognized international court Prosecute means “To initiate civil or criminal court action against.” And Crimes Against Humanity, according to the ICC, means ““An international criminal justice offence; the perpetration of acts of war upon a civilian, non-soldier population.” You can see an expanded definition at Duhaime.org’s legal dictionary.

My value for this round is justice, since the resolution asks a question about international law. Focusing this round on justice is the best way to garner topical education from this topic.

My Criterion is the prevention of genocide – I will argue that submitting to the jurisdiction of the ICC will provide the greatest justice for the global population by eliminating the worst form of injustice.

Contention One: The ICC will fail to provide justice without US adherence The United States is the biggest world power, and supported the ICC in its creation, but has since refused to provide leverage for it’s jurisdiction by ratifying the Rome Statute. As Roseann M. Latore, an editor for the Boston College International & Comparative Law Review, writes in 2002, The opinion of the international community is that, without the participation of the United States, the ICC will be "maimed at birth." Most nations desire the inclusion of the United States because it alone has the ability to ensure that criminals sought by the ICC are brought to trial. The United States' participation in the ICC, therefore, would provide the credibility and the strength the ICC needs to be effective. Roseann M. Latore, Solicitations Editor & Symposium Chair of the Boston College International & Comparative Law Review, Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, Winter, 2002, p. 164

Furthermore, US ratification of the ICC would send an overwhelming signal of long-term commitment to international law. As Department of State Legal Advisor John Bellinger writes, I. U.S. treaty practice demonstrates commitment to international law . . . The press . . . tends to focus on a small number of treaties . . . transformed into symbols for what is seen as the United States' hostility to international law and global cooperation. [*637] In reality, our treaty practice reflects the seriousness with which we take international obligations, not our indifference to them. . . . During negotiations, we try to eliminate ambiguities and pin down important questions of policy. . . . [W]e don't do this to be obstructionist. . . . This is in part a matter of good draftsmanship, and an attempt to head off disputes and pro-mote compliance. But it is also a reflection of the reality in which we operate: We need to explain to our Senate exactly what obligations we are taking on . . . . This accountability . . . also explains why we are so careful . . . to determine whether we need to subject our ratifi-cations of treaties to any reservations or understandings and why we make sure to line up any implementing legislation in advance. . . . [W]e do not join treaties lightly, as a goodwill gesture, or as a substitute for taking meaningful steps to comply. Ironically, this rigorous approach is sometimes seen . . . as a sign of hostility. In part, this can be traced to a wide-spread view that willingness to join a treaty is a litmus test of a country's commitment to international law. Under this view, joining a treaty is good; not joining a treaty, or expressing concerns . . . are the excuses of a nation unwilling to shoulder international responsibilities. John Bellinger, quoted in: John R. Crook, Contemporary Practice Of The United States Relating To International Law: General International And U.S. Foreign Relations Law: State Department Legal Adviser Describes U.S. Views On International Law, Suggests Possible Cooperation With International Criminal Court On Darfur, The American Society Of International Law American Journal Of International Law July, 2007

13 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

This strengthening of the international justice system is crucial in establishing global human rights standards that can prevent future genocides. National sovereignty must be made submissive to international justice. As Michael Ignatieff, member of the independent international commission on Kosovo, said in a lecture on Human Values at Princeton University in April 2000 We know from historical experience that when human beings have defensible rights—when their agency as individuals is protected and enhanced—they are less likely to be abused and oppressed. On these grounds, we count the diffusion of human rights instruments as progress even if there remains an unconscionable gap between the instruments and the actual practices of states charged to comply with them. Calling the global diffusion of Western human rights a sign of moral progress may seem Eurocentric. Yet the human rights instruments created after 1945 were not a triumphant expression of European imperial self-confidence but a reaction on European nihilism and its consequences, at the end of a catastrophic world war in which European civilization very nearly destroyed itself. Human rights was a response to Dr. Pannwitz, to the discovery of the abomination that could occur when the Westphalian state was accorded unlimited sovereignty, when citizens of that state lacked criteria in international law that could oblige them to disobey legal but immoral orders. The Universal Declaration represented a return by the European tradition to its natural law heritage, a return intended to restore agency, to give individuals the juridical resources to stand up when the state ordered them to do wrong. 2. The Juridical, Advocacy, and Enforcement Revolutions Historically speaking, the Universal Declaration is part of a wider reordering of the normative order of postwar international relations, designed to create fire-walls against barbarism. The juridical revolution included the UN Charter of 1945, outlawing aggressive war between states; the Genocide Convention of 1948, protecting religious, racial, and ethnic groups against extermination; the revision of the Geneva Conventions of 1949, strengthening noncombatant immunity; and finally the international convention on asylum of 1951 to protect the rights of refugees. Before the Second World War, only states had rights in international law. With the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, the rights of individuals received international legal recognition.3 For the first time, individuals—regardless of race, creed, gender, age, or any other status—were granted rights that they could use to challenge unjust state law or oppressive customary practice. Michael Ignatieff, member of the independent international commission on Kosovo, chaired by Judge Richard Goldstone of South Africa. Former fellow at King’s College, Cambridge; École des Hautes Études, Paris; and St. Antony’s College, Oxford; and Visiting Prof of Human Rights Practice at Harvard. “I. Human Rights as Politics II. Human Rights as Idolatry,” The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Princeton University April 4–7, 2000 http://www.tannerlectures.utah.edu/lectures/Ignatieff_01.pdf

Finally, we have a moral obligation to do everything we can to support efforts to prevent genocide. It is an immeasurable tragedy worse than physical death. As Claudia Card, a philosophy professor at the University of Wisonsin-Madison, writes in 2003, When a group with its own cultural identity is destroyed, its survivors lose their cultural heritage and may even lose their intergenerational connections. To use Orlando Patterson's terminology, in that event, they may become "socially dead" and their descendants "natally alienated," no longer able to pass along and build upon the traditions, cultural developments (including languages), and projects of earlier generations (1982, 5-9). The harm of social death is not necessarily less extreme than that of physical death. Social death can even aggravate physical death by making it indecent, removing all respectful and caring ritual, social connections, and social contexts that are capable of making dying bearable and even of making one's death meaningful. In my view, the special evil of genocide lies in its infliction of not just physical death (when it does that) but social death, producing a consequent meaninglessness of one's life and even of its termination. This view, however, is controversial. Claudia Card, Philosophy Prof @ U of Wisconsin-Madison. "Genocide and Social Death," Hypatia, Vol.18, Iss. 1 2003

14 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

The ICC Prevents Genocide

A strengthened ICC would send a strong signal capable of preventing genocides. Sharon A. Williams, a Professor of Law at Osgoode Hall Law School, suggests that an organized international justice system could have changed the shape of history. Would a real threat of prosecution together with enforcement capability have made a difference to the course of history? In all likelihood the answer is yes. In 1936, in a speech made at a Nuremberg rally, Adolf Hitler addressed the perceived ineptitude on the part of states collectively to take effective action against governments or individuals for committing international crimes. In referring to the Armenian holocaust, where Turkish officials allegedly killed over one and a half million Armenians during the First World War, he asked rhetorically: "Who after all is today speaking about the destruction of the Armenians?" A dangerous signal was sent to Hitler and subsequent ruthless leaders when the Allied Powers failed to bring to justice those allegedly responsible in Turkey. The underlying philosophy was that the international community would do nothing and monstrous crimes could be committed with impunity. Had strong, united, international cooperation existed, perhaps Hitler in Germany and elsewhere in Eastern and Western Europe, Idi Amin in Uganda, Pol Pot in Cambodia, Saddam Hussein in Iraq and Kuwait, Radovan Karadzic and Slobodan Milosevic in the Former Yugoslavia, Jean Kambanda in Rwanda, Hissene Habre in Chad, and Foday Sankoh in Sierra Leone may have been deterred from perpetrating the widespread and systematic atrocities that the world has witnessed. Sharon A. Williams, Professor of Law, Osgoode Hall Law School, Osgoode Hall Law Journal, Summer, 2000, p. 298

15 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

The ICC Prevents Gender Crime

The ICC can succeed in providing justice for gender-based crimes Tina R. Karkera, J.D. Candidate, Washington College of Law, American University, 2004. THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT'S PROTECTION OF WOMEN: THE HANDS OF JUSTICE AT WORK, 2003 12 Am. U.J. Gender Soc. Pol'y & L. 197 Where other international courts have failed with regard to gender-based crimes, the ICC is expected to succeed. n38 The Rome Statute grants the ICC jurisdiction over four major areas of crimes: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and aggression. n39 The ICC Prosecutor n40 can choose to prosecute gender-based crimes under either crimes against humanity or war crimes. n41 [*205] The Rome Statute's inclusion of gender provisions did not occur independent of precedent or history. n42 Cases prosecuted in the ICTY, as well as later on in the ICTR, played a crucial role in the inclusion of such provisions in the Rome Statute. n43 Equally influential as the ICTY and ICTR statutes and case law were advances on gender violence issues made within the United Nations. n44 II. Protecting Women: Articles 7 and 8 The Rome Statute broadened the ICC's jurisdiction and made gender-based crimes an international concern. n45 Article 7 of the Rome Statute addresses crimes against humanity; n46 Article 8 addresses [*206] war crimes, n47 and both these articles include gender-based crimes as prosecutable crimes. n48 Furthermore, the ICC has jurisdiction over individuals, not states, engaged in crimes. n49

16 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

International Law Provides Justice

International legal protections provide a mechanism for dispossessed peoples to shame the state and eliminate oppression. As Marcus Raskin, Professor of Public Policy at the George Washington University Graduate Program, writes: Acheson was defending white Rhodesia against the black African majority and the emerging hardy band of international lawyers who insisted on international law based in the spirit of morality. 34 Of course, Acheson patronized those such as the wise Quincy Wright, and even Grenville Clark and Louis Sohn, for he knew that if their ideas caught on, if their ideas jumped classes to reach and link to the ideas and struggles of the angry and dispossessed, and if the dispossessed were to escape the THM framework, law would become a threat to naked power. The United States and the West would have been inhibited in defining the world's social development. After all, what else are the curious phrase "nation-building" and the concept of globalization, other than materializations of an attempt to define the structure of national cultures without including one's own in the crucible of interaction, except as imperial guide? But abstract language and law are curious instruments of world historical development. In the hands, hearts and minds of people they can become quite unpredictable, especially when aided by new readings of the law which have a moral core. What must be surely irritating to the colonizers is that this hardy band used the rhetorical explanation and rationalization of realpolitik, as used by nation-states, as legal jiu jitsu for catalyzing autonomous groups to argue for human rights, freedom and even economic rights. Surely this is what happened with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 35 and what may become true of the covenants on political, economic and social rights. 36 This jiu jitsu was based on more than legal skill. It stemmed from those traditions which had roots in natural law, the Declaration of Independence, recognition of human dignity and pragmatic progress. The philosopher Richard McKeon's claim that cultural rights were fundamental to all other rights 37 helped to justify and give shape to the changing context for international law and politics, one which necessarily included different cultures beneath and beyond the nation-state. Marcus Raskin, Professor Of Public Policy Graduate Program, George Washington University. “Re-Framing International Law For The 21st Century: The International Law Of Reconstruction,” Transnational Law & Contemporary Problems Fall, 1999 9 Transnat'l L. & Contemp. Probs. 513

17 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

A2: The US Won’t Enforce the ICC

Even if the ICC were unenforceable, adhering to its jurisdiction would send a strong signal that the US was committed to human rights, which are vital in preventing genocide. Our State Department Legal Advisor John Bellinger believed that.

And, he also believes that US submission would be entirely genuine. We would commit to enforcing the ICC’s decisions. John Bellinger writes again, Today's world presents many challenges, from transnational terrorism to economic interdependence to global warming, AIDS, and possible future pandemics to the eternal quest for human dignity and lib-erty. The United States believes that collective action and international law are essential in coordinating the international community's approach to these deep and difficult problems. . . . [T]he U.S. role in the world makes international law more important to us, not less. We do not seek to impose constraints on others but shrink from them ourselves. Our careful approach to treaty negotiation and treaty acceptance reflects our respect for international law, not a desire to be free of it. When we assume international obli-gations, we take them seriously and seek to meet them, even when doing so is painful. And where inter-national law applies, all branches of the U.S. government, including the judiciary, will enforce it. n7 John Bellinger, quoted in: John R. Crook, Contemporary Practice Of The United States Relating To International Law: General International And U.S. Foreign Relations Law: State Department Legal Adviser Describes U.S. Views On International Law, Suggests Possible Cooperation With International Criminal Court On Darfur, The American Society Of International Law American Journal Of International Law July, 2007

18 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

A2: National Sovereignty Is More Important

1. US refusal to adhere to the ICC is more damaging to US national security than compliance Peggy E. Rancilio, University of Detroit Mercy Law Review, Winter, 2001, p. 337 In the end, "it will cost America less in blood and treasure if international stability and security are based on the rule of law, backed up by economic and military might, rather than based on might alone." U.S. reliance on might alone will often result in the U.S. standing alone. The lack of U.S. support ultimately weakens the strength of the court and provides rouge leaders with some comfort that the court will not be a serious threat to them. "To condemn massive atrocities, without creating an effective method to apprehend and bring the criminals to justice, is to mock the victims and encourage more criminality."

2. The ICC strengthens United States hegemony by sharing burdens and enhancing stable multilateralism Andrew J. Walker, Assistant District Attorney, Galveston County, Texas, Winter ’04, WEST VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW, no. 245, p. 256 The existence of a strong ICC is in the United States' best interest. On a primary basis, while the United States cannot rely on most states to carry out their international obligations and must be able to protect itself from international outlaws, it cannot be required to take on all of the world's burdens. An effective international criminal court is capable of alleviating this burden by maintaining security abroad where the United States cannot or should not act. Ideally, it can force the elites of a country to respect the severity of the consequences to be imposed by political risks of international criminal acts. Furthermore, it can compel national leaders to recognize the need for an international system of multilateral accountability to replace the former bipolar political status of the Cold War. This deterrence capability remains even if it is unrealistic to expect an institution based on the Kantian ideal of interdependence amongst sovereigns to serve as a reliable prophylactic to crimes against humanity.

19 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

A2: Alternative Courts Are Better

Even if other international courts are potentially more effective than the ICC, international perception means that no one will support anything else Jean Galbraith, JD Candidate, 2004, School of Law, University of California at Berkeley, BETWEEN EMPIRE AND COMMUNITY: The United States and Multilateralism 2001-2003: A Mid-Term Assessment: HUMANITARIAN LAW The Bush Administration's Response to the International Criminal Court, Berkeley Journal of International Law 2003 21 Berkeley J. Int'l L. 683 Given that the ICC was created as a permanent forum for bringing war criminals to justice and has the backing of a substantial number of the world's nations,n62 the United States must consider how its approach to the ICC will affect its ability to play a major role in bringing future war criminals to justice. The collective effort in creating the ICC was enormous, n63 and the United States [*693] participated seriously in this effort.n64 It may now prove difficult to generate international support for the international prosecution of war criminals via other means. Besides the political difficulties of getting Security Council authorization for any such prosecution (authorization which would still be needed for certain ICC prosecutions), ICC party nations may not want to put funds and energy into other tribunals besides the ICC, thus perhaps making particularly challenging the U.S. goal of achieving the international prosecution of war criminals through other means.

20 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

A2-Hybrid Courts are Better

1. There won’t be any more hybrid courts Remigius Oraeki Chibueze, Attorney-at-Law and Counselor, State Bar of California; Solicitor & Advocate of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT: BOTTLENECKS TO INDIVIDUAL CRIMINAL LIABILITY IN THE ROME STATUTE, Spring 2006, 12 Ann. Surv. Int'l & Comp. L. 185 After the establishment of the ICC, it is very unlikely that the international community may establish another ad hoc international or hybrid criminal tribunal to prosecute persons accused of international crimes. n178 Thus, the continued application of international individual criminal responsibility rests with the Court.

2. Joining the ICC will not undermine hybrid courts Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 The ICC's establishment has already had a significant impact on the world of international justice. However, it cannot cope with more than a small fraction of the world's war crimes cases. This is where hybrid courts come in. Indeed, the potential for ICC-hybrid symbiosis speaks to the heart of hybrids' importance. n320 Hybrids will neither undermine the ICC nor be rendered superfluous by the ICC.

3. Hybrid courts are manipulated by local populations to prevent the establishment of justice Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 One of the hybrid model's most serious potential flaws is that instead of incorporating the best of both international and local judicial systems, it may reflect the worst of both. Ideally, hybrids' value lie in their fluidity and ability to adapt to local culture, language, and law while maintaining the core values of international criminal law, which anchor them, and impart credibility and a measure of impartiality. However, their very capacity to adjust to local realities in an effort to better serve indigenous populations could be manipulated, and their flexibility could morph into volatility and confusion. The further hybrids deviate from an international tribunal prototype, the more they risk being manipulated by ethnic, military, or political factions, and they can still become kangaroo courts, valuing expediency at the expense of proper procedure.

4. Hybrids can alienate local populations and suffer from underfunding and lack of leadership Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 Just as hybrids can drift too far towards the Scylla of flawed local justice, they can also stray towards the Charybdis of disconnected international justice. Too great a reliance on international structures and visions can create a chasm between the court and local populations, a brand of justice that smacks of imperialism and is not anchored in local culture. A promising model which overcomes some inherent flaws of international and local courts does not necessarily provide answers to all problems. Like any judicial institution, hybrids need leadership, independence, good management, and funding.

5. Hybrid courts are too weak to target powerful individuals Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 Hybrids share many of the problems experienced by national courts. It can frequently be dangerous for war crimes trials to take place in situ - local and hybrid courts run the risk of being influenced by the very agents that perpetrated or ordered the crimes in question. Trying heads of state or powerful army, paramilitary, and police leaders in their former fiefdoms when they retain significant support bases can be enormously dangerous. n234 Even incarcerating [*412] perpetrators might "not be feasible if their supporters retain significant military or paramilitary power to force their release."

21 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

A2-Hybrid Courts are Better

6. Hybrid courts yield sham trials that exacerbate ethnic tensions Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 Hybrids may also flounder if the crimes they adjudicate were committed or endorsed by elites who were not truly ousted by the post-conflict change in regime. n237 Local participation in hybrid tribunals can thus open the door to "sham trials by insincere regimes implicated in the very atrocities adjudicated." n238 On the opposite extreme of the spectrum, local input can also create a space for "political [*413] show trials by successor regimes bent on vengeance instead of justice [such that the trials] are not likely to advance the rule of law at either the national or international levels." n239 With severe ethnic, tribal, and political divisions among the local population, a hybrid court can fan flames of local strife, raising perceptions of bias or favoritism if members of one group are appointed over others.

7. Hybrid courts fail due to lack of experienced workers Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 Hybrid courts face many of the logistical and training difficulties of local trials. Since they hire locals and use local infrastructure, their work can be constrained by damaged infrastructure or a lack of experienced lawyers, judges, investigators, analysts, etc. in the country.

8. Hybrid courts create a confusing patchwork that prevents international justice Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 Another possible dire consequence of a patchwork of hybrid courts would be "a fragmentation of international criminal law, whereby different [*414] substantive rules emerge in different regions." n240 With independent hybrid tribunals adjudicating similar legal issues, but without any hierarchy, review procedures, principle of stare decisis, or even court-to-court comity, a crisis could loom with multiplying variations in the substance of international law. Whereas potentially dangerous splits in U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals on key legal issues are resolved by the United States Supreme Court's writ of certiorari, which promotes uniformity, "the emergent system of international criminal law has neither a high court of review nor a requirement of stare decisis." n241 Jonathan Charney explains the danger: "Significant variations in general international law . . . could undermine the perceived uniformity and universality of international law." n242 The net result could be that "the increased multiplicity of international dispute settlement forums may present particular difficulties for the international legal system." n243 Variations in substantive rules of international criminal law might create havoc n244 for several reasons: First, international crimes that are supposedly universal in nature would lose their sense of universality and global condemnation as they come to have regional variation. Second, loopholes might be created whereby perpetrators of international crimes could avoid conviction by relying on regional variation in the definitions of crimes. Third, judges in certain regions could possibly reshape international criminal law to allow particular individuals to avoid conviction. n245 [*415] Ultimately, under the "pressure of divergent norm enunciation by different hybrid courts, international criminal law's legitimacy could crumble, given the fragile nature of the nascent body of law."

22 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

A2-Ad Hoc Tribunals are Better

1. Ad hoc tribunals are being phased out because they are ineffective Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 Ad hoc international tribunals' days appear to be numbered. This is largely because the ICTY and ICTR's cost has produced tremendous donor fatigue, although their inherent weaknesses and inability to communicate effectively with local populations have not sparked the criticism they deserved. Both of these tribunals are being forced to speed up operations in anticipation of closing shop. n331 The clock is ticking all the more urgently to find viable alternatives to ad hoc tribunals.

2. Ad hoc tribunals create confusion and gridlock Jean Galbraith, JD Candidate, 2004, School of Law, University of California at Berkeley, BETWEEN EMPIRE AND COMMUNITY: The United States and Multilateralism 2001-2003: A Mid-Term Assessment: HUMANITARIAN LAW The Bush Administration's Response to the International Criminal Court, Berkeley Journal of International Law 2003 21 Berkeley J. Int'l L. 683 The Bush administration may manage to persuade the Security Council to set up an ad hoc tribunal for dealing with Saddam Hussein and his officials. For future war criminals, however, the United States may have a difficult time getting such tribunals through the Security Council. The ICC may appear a logical venue to other Security Council members for war criminals whose crimes (unlike those of Saddam Hussein) occurred primarily after the ICC's jurisdiction began on July 1, 2002. Furthermore, the ICC itself may initiate investigations of such war criminals if they come from party nations or committed their crimes on the territory of other party nations. Any attempt by the Security Council to set up a competing tribunal might cause complication, confusion, and gridlock.n101

3. Ad hoc tribunals fail and probably won’t be created again Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347 Runaway costs, management flaws, and communication failures in the ad hoc tribunals in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia have generated fatal donor fatigue n1 and called into question the efficacy of international criminal justice. For this reason, it is unlikely that an ad hoc international tribunal will be created again.

23 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

SECTION 5 – THE NEGATIVE

EXAMPLE NEGATIVE CASE

I negate this resolution:

First, I would like to define “international court” as an independent authority that can make legal decisions that supersede the national laws of participant nations Hans Kelsen, Naval War College (U.S.), 2001, Collective Security Under International Law, p.124 Insofar as an international court is a common court of the states which are contracting parties to the treaty by which a court or its jurisdiction is established, an international court can try individuals for having violated international law by acts of state, and this means in their capacity as organs of a state, only with the consent of this state.

My value for this round is justice.

My criterion is sustainability in international law. Justice will be best served by refusing to submit to international courts, which crowd out hybrid courts that are better able to solve humanitarian crises and establish indigenous judiciaries capable of creating international justice.

Contention One is that hybrid courts are an alternative to international courts that combine international and national or subnational judiciaries based on local circumstances. As Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, writes: However, despite ambiguities in definitions of hybrid courts, some baseline characteristics emerge. Hybrids blend the international and the domestic with legal and organizational innovations that constitute important divergences from international ad hoc tribunals. In some cases they coexist with the local judiciary, operating in parallel, while in others, they have been grafted onto the local judicial system. But in all cases their nature is mixed. Usually, they are composed of international and local staff with foreign judges sitting alongside their domestic counterparts to try cases prosecuted and defended by teams of both local and foreign lawyers. Domestic law--reformed to include international standards--is typically applied alongside international law. Ultimately, hybrid criminal bodies form a family of their own, apart from other judicial entities. Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347

Contention Two is that lending support for international courts would effectively destroy these hybrid courts in favor of universal laws that ignore the contexts of humanitarian crises. As the US demonstrated the advantages of international courts, countries would stop supporting hybrid courts. Support for an international court is directly proportional to neglect for hybrid courts and ad hoc tribunals. In other words, to express respect for an international court would be to express disrespect for hybrid courts.

24 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

Contention Three is that this tendency is worse for international justice. International courts are unsustainable due to perceptions of imperialism. The world must abandon international courts in favor of hybrid alternatives. Etelle R. Higonnet explains again how hybrid courts are comparatively better at fostering sustainable international justice and resolving humanitarian crises, when she writes: However, this does not imply that international courts are the only alternative. Despite the dangers of integrating local elements with international justice, and of hybrids diverging in their interpretation of international law, the benefits of abandoning a cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all, international approach to trying war crimes outweigh the disadvantages. Domestic courts and realities on the ground may be troubling, murky, and dangerous, but bypassing local input is even more problematic than including it. Local culture plays an indispensable part in any long term solution to post-atrocity rebuilding. If donor countries or the U.N. are to succeed in changing a country for the better, they "cannot display an elitist, paternalistic attitude" toward war crimes victims and national judiciaries, "i.e., viewing local participation as inherently biased, tribal, inexperienced, and inept." n22 Doing so jeopardizes the goal of indigenous reform and empowerment, leaving us with the alternative of perpetual international oversight--at once unsustainable in practical terms, and dubious in moral terms, given its inherent imperialism. Etelle R. Higonnet, Bernstein Fellow in the Africa Division of Human Rights Watch, Spring 2006, RESTRUCTURING HYBRID COURTS: LOCAL EMPOWERMENT AND NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM, Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23 Ariz. J. Int'l & Comp. Law 347

Thus, I negate the resolution. The United States ought not submit to the jurisdiction of an international court as long as there exist better alternatives like hybrid courts, which can only survive in the absence of a stronger central international judiciary that is unwilling to incorporate localized legal structures and opinions.

25 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

International Courts Fail Because of US Manipulation

Merely submitting to the jurisdiction of an international court does not guarantee US compliance. The US will always pursue its national interests and will not suddenly change its priorities away from illegal unilateralism. That means that the affirmative case is backwards – the US will demonstrate the weakness of international law when it flouts international courts

1. The perception that the United States has excessive political power in an international court will destroy international justice. Thomas M. Franck, Board of Editors, the American Journal of International Law, January 2006, CENTENNIAL ESSAY: THE POWER OF LEGITIMACY AND THE LEGITIMACY OF POWER: INTERNATIONAL LAW IN AN AGE OF POWER DISEQUILIBRIUM, 100 A.J.I.L. 88 Importantly, while this sounds like a purely descriptive-empirical observation, it also has enormous prescriptive potential. If this power-realism is the prism through which law's purchase is to be understood in the future, that perception -- right or wrong as a description of the present -- can indeed become a self- fulfilling prophecy. In any society, but especially among states, the compliance pull of law is based on the expectation of each participant that most others, most of the time, will obey the law -- all of it, not just some subsets, and not only when it [*91] is in their immediate interest to do so.

2. If the US doesn’t comply with an international court’s jurisdiction, international law will fall into anarchy Thomas M. Franck, Board of Editors, the American Journal of International Law, January 2006, CENTENNIAL ESSAY: THE POWER OF LEGITIMACY AND THE LEGITIMACY OF POWER: INTERNATIONAL LAW IN AN AGE OF POWER DISEQUILIBRIUM, 100 A.J.I.L. 88 The real power of law to secure systematic compliance does not rest, primarily, on police enforcement -- not even in police states, surely not in ordinary societies, and especially not in the society of nations -- but, rather, on the general belief of those to whom the law is addressed that they have a stake in the rule of law itself: that law is binding because it is the law. That, of course, is a fragile psychological belief, one, moreover, that is unverifiable. While, in every community, it constitutes an essential social construct, it is easily deconstructed. If one were able to ask the bumblebee, with its aerodynamically unviable body-to-wing ratio, how it manages to fly, it might well fall to the ground. A grave responsibility is thus incurred by those who undermine the general belief in the independent capacity of law to affect compliant behavior, even if they direct their attack to one particularly vulnerable subset of laws. For, in essence, the debate is not merely about Article 2(4) of the UN Charter. It is not just about whether a universal treaty adhered to by 191 countries is a disposable instrument. It is about the weighing of power against legitimacy. It is a struggle for the soul of the community of nations. That struggle will be waged with the weaponry of facts, but, more important, with that of perceptions. When a community loses faith in law's power to restrain and channel conduct, this perception propels the descent into anarchy.

3. Noncompliance with the ICC will destroy its credibility Remigius Oraeki Chibueze, Attorney-at-Law and Counselor, State Bar of California; Solicitor & Advocate of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT: BOTTLENECKS TO INDIVIDUAL CRIMINAL LIABILITY IN THE ROME STATUTE, Spring 2006, 12 Ann. Surv. Int'l & Comp. L. 185 Thus, "a decision by the Prosecutor to bring charges against an accused will prompt the critical, indeed crucial question of arrests and transfer to The Hague." n148 In other words, the Court would be unable to exercise its jurisdiction if States refused, delayed or otherwise failed to carry out their obligation to arrest and/or surrender the accused to the Court. There is no doubt that "the credibility of the Court would suffer if an arrest warrant issued by the judges of the Pre-Trial Chamber at the request of the prosecutor pursuant to Article 58 remained ineffective over a long period because the States Parties were slow, or failed, to execute it." n149

26 West Coast Publishing 2008 NFL LD-International Courts

The ICC Fails Because of UN Predetermination