Hypoxyphilia

Volume XVI, No. 4 • Winter 2004 New Members

Standards Update

New ATSA Awards Program

David Prescott, L.I.C.S.W. Click here to Front Page Forum Editor download a Word President's Column printable version

Hypoxyphilia

Review of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist - Revised: 2nd Edition

Book Reviews Dear ATSA Colleagues:

Ethics Committee Report I hope that you had a wonderful holiday season. For me, this column not

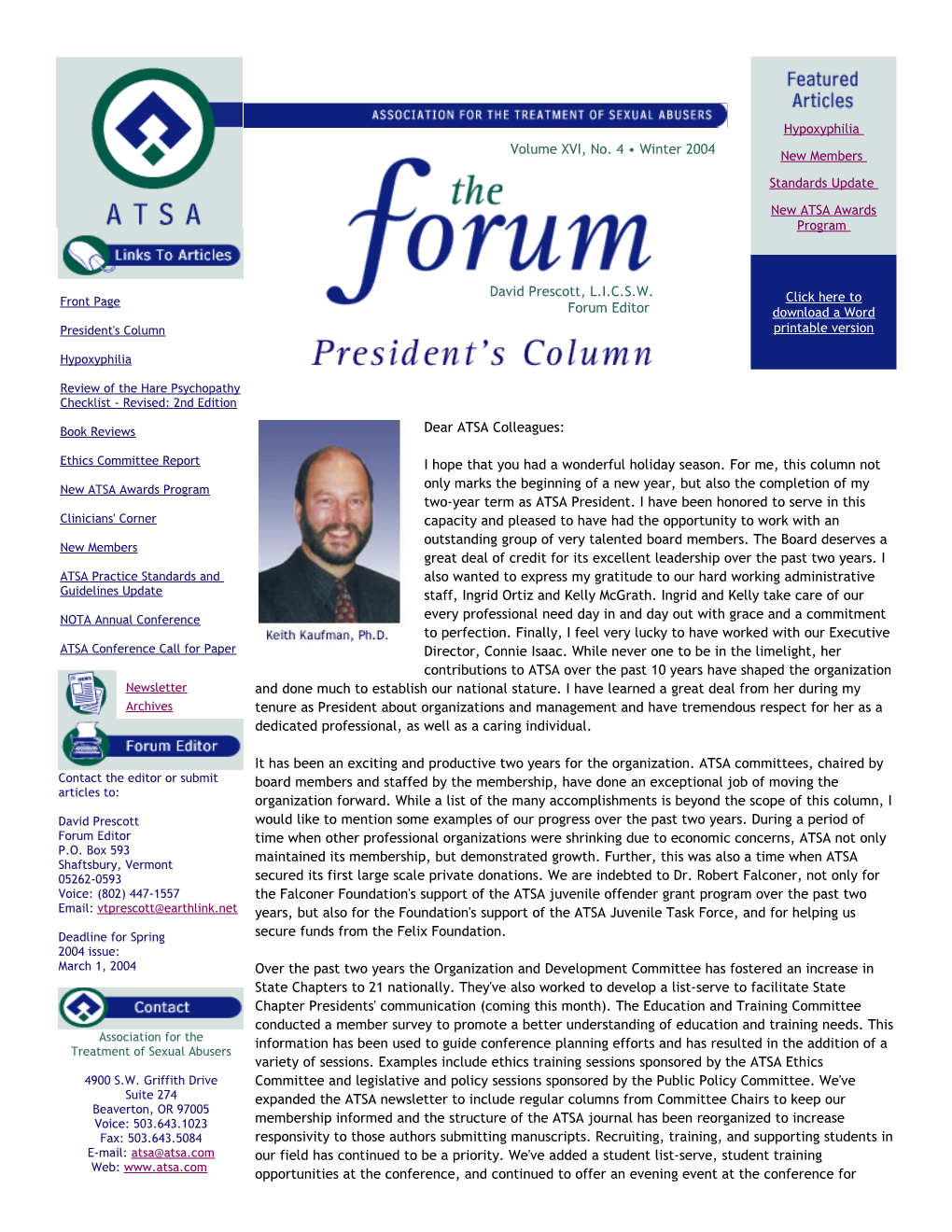

New ATSA Awards Program only marks the beginning of a new year, but also the completion of my two-year term as ATSA President. I have been honored to serve in this Clinicians' Corner capacity and pleased to have had the opportunity to work with an outstanding group of very talented board members. The Board deserves a New Members great deal of credit for its excellent leadership over the past two years. I ATSA Practice Standards and also wanted to express my gratitude to our hard working administrative Guidelines Update staff, Ingrid Ortiz and Kelly McGrath. Ingrid and Kelly take care of our

NOTA Annual Conference every professional need day in and day out with grace and a commitment to perfection. Finally, I feel very lucky to have worked with our Executive ATSA Conference Call for Paper Director, Connie Isaac. While never one to be in the limelight, her contributions to ATSA over the past 10 years have shaped the organization Newsletter and done much to establish our national stature. I have learned a great deal from her during my Archives tenure as President about organizations and management and have tremendous respect for her as a dedicated professional, as well as a caring individual.

It has been an exciting and productive two years for the organization. ATSA committees, chaired by Contact the editor or submit board members and staffed by the membership, have done an exceptional job of moving the articles to: organization forward. While a list of the many accomplishments is beyond the scope of this column, I David Prescott would like to mention some examples of our progress over the past two years. During a period of Forum Editor time when other professional organizations were shrinking due to economic concerns, ATSA not only P.O. Box 593 maintained its membership, but demonstrated growth. Further, this was also a time when ATSA Shaftsbury, Vermont 05262-0593 secured its first large scale private donations. We are indebted to Dr. Robert Falconer, not only for Voice: (802) 447-1557 the Falconer Foundation's support of the ATSA juvenile offender grant program over the past two Email: [email protected] years, but also for the Foundation's support of the ATSA Juvenile Task Force, and for helping us

Deadline for Spring secure funds from the Felix Foundation. 2004 issue: March 1, 2004 Over the past two years the Organization and Development Committee has fostered an increase in State Chapters to 21 nationally. They've also worked to develop a list-serve to facilitate State Chapter Presidents' communication (coming this month). The Education and Training Committee conducted a member survey to promote a better understanding of education and training needs. This Association for the information has been used to guide conference planning efforts and has resulted in the addition of a Treatment of Sexual Abusers variety of sessions. Examples include ethics training sessions sponsored by the ATSA Ethics 4900 S.W. Griffith Drive Committee and legislative and policy sessions sponsored by the Public Policy Committee. We've Suite 274 expanded the ATSA newsletter to include regular columns from Committee Chairs to keep our Beaverton, OR 97005 Voice: 503.643.1023 membership informed and the structure of the ATSA journal has been reorganized to increase Fax: 503.643.5084 responsivity to those authors submitting manuscripts. Recruiting, training, and supporting students in E-mail: [email protected] our field has continued to be a priority. We've added a student list-serve, student training Web: www.atsa.com opportunities at the conference, and continued to offer an evening event at the conference for students to have time to discuss their ideas with leading researchers in the field. The Professional Issues Committee has just released a new draft of the ATSA Standards and Guidelines for members' comments. We have created time-limited task forces in the adult, juvenile/prepubescent, and prevention areas. These expert panels will be developing "white papers" intended to guide the field, our practice, and our research. Finally, we've worked hard to establish and/or enhance collaborations with organizations in related fields (e.g., American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Sex Offender Management, National Alliance to End Sexual Violence). These efforts have led to a number of important opportunities, strengthen our position on the national scene, and will likely lead to models that enhance community safety.

Thanks to all of you who have contributed to the growth of ATSA, the promotion of the field, and the enhancement of community safety. We have made considerable progress, but there is still much to do. There are many opportunities for your input and participation. Please continue to be active, vocal, and a positive force.

I leave you in the very capable hands of our new President, Dr. Ray Knight.

Best wishes for the coming year!

Keith L. Kaufman, Ph.D. ATSA Past President

Keith L. Kaufman, Ph.D. ATSA Past President Stephen J. Hucker, MB, BS, FRCP(C), FRC Psych. Professor and Academic Head Forensic Division Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences McMaster University Hamilton, Ontario

Among the many varieties of abnormal sexual behavior or paraphilia encountered by ATSA members the most unusual and perplexing will likely include what DSM IV refers to as "hypoxyphilia," a sub- category of sexual masochism. Elsewhere the same phenomenon may be called asphyxiophilia, autoerotic or sexual asphyxia among other terms. Later I will discuss what is in fact the most appropriate label, but for now I will define it as: "the production of sexual arousal using techniques that cause hypoxia (reduced oxygen supply to the brain)." These techniques typically involve self- hanging or strangulation, suffocation, or other rarer methods.

Of course masochists may engage in many different sexually stimulating activities that can cause self-harm or even death. These include the use of electrical stimulation or inhalation of drugs that cause cardiac arrhythmias.

Hypoxyphilia has been known to medical science for nearly two hundred years, and to others perhaps since antiquity, but most of what we know about it has come from the study of cases in which a mishap has occurred and the individual has died. Such fatalities occur with a frequency of about one per million of the population per year in North America though this figure is based on studies of cases that have been recognised. Even today, when the phenomenon is quite widely known, it appears that many are still mis-classified as suicides and sometimes as homicides, by persons unknown. Apart from unfamiliarity with this mode of death itself, investigation into the death may be hindered when well-meaning family members and friends remove embarrassing items, such as sexually explicit materials, that would otherwise make classification more straightforward.

Those who have studied these deaths have noted several distinguishing features. Some are clearly essential but others are not always present or the evidence may be ambiguous.

First, it should always be possible to show how the individual would have intended to control the degree of hypoxia and to escape from the situation. The intention is to survive the ritual not die from it, as might appear at first glance. When death occurs it is almost always due to the failure of a strategy intended to ensure recovery. There is no evidence that hypoxyphilia is some form of disguised suicide. Many authorities have insisted that a "fail-safe" device is invariably found but in my experience the strategy may often have been simply reliance on subjective judgement, as by releasing hold on a ligature or pulling off a plastic bag, when a feeling of giddiness supervenes.

Second, there must be evidence of sexual activity. Often the body may be found either nude, partially nude, or with the penis projecting through an open fly, perhaps with the hand touching the genitals as if frozen in the act of masturbation. Ejaculation may have occurred though the latter can occur in other types of death and is not a conclusive sign. Cross-dressing in female clothing is a feature in about a quarter of the cases.

An indication of the importance of sexual fantasy to the hypoxyphile is that various forms of pornography and other sexual paraphernalia are often found at the scene or among the deceased's personal possessions. Sometimes a mirror will have been placed strategically near the body to allow the subject to view himself as he performs his ritual or a camera may have been set up so that the person may photograph or videotape himself during his ritual. Others will create an entire environment that relates to some special fantasy and may involve, for example, the creation of a torture chamber or other obviously sado- masochistic theme. Often the elaborate nature of the equipment used in these cases make it clear that the behavior has been carried out many times before, or there may be other evidence of repetition, such as grooved beams from which ropes have been suspended. Some authorities have regarded this as an essential feature of the syndrome but, as they are not always present in otherwise obvious cases, this is disputable. Although often a rope or other ligature is the method whereby hypoxia is induced, ligatures and bindings may also be present that are not involved in the asphyxiating process but were obviously important to the deceased. Sometimes these bindings may be very elaborate indeed.

Nearly all the reported cases of hypoxyphilia have been males and most are under forty years old at the time of death. As for any masturbatory activity, the individual usually chooses a private or secluded place. Death scenes in these locations vary considerably in complexity and many forensic texts describe a typical case as involving complex elements including elaborate asphyxiating devices. However, in my own series of 171 fatal cases, most were relatively uncomplicated and not all of the more bizarre features are necessarily present.

The methods used to produce hypoxia include self-hanging, strangulation, choking, suffocation and techniques to restrict breathing movements. Hanging is the commonest method among fatal cases. Suffocation or reduction of the oxygen in the inspired air may be achieved with plastic bags, masks or more complicated apparatus involving some other kind of head covering. Sometimes anaesthetics, other gases or volatile chemicals will be included or, on occasion used alone, and administered by some other means.

In most cases hypoxyphilic deaths are a complete surprise to family and friends as the deceased was typically in a good mood and giving every indication that they were looking forward to the future. There is no relationship between hypoxyphilia and mental or personality disorder but there is clearly an association with other paraphilias, which have a tendency to cluster in other circumstances as well. Thus other, more typical masochistic behaviors are frequently noted among hypoxyphilic fatalities, though most other common paraphilias have also been reported.

In contrast to fatal cases, where we must necessarily discover about the person retrospectively, there have been relatively few reports of living hypoxyphiliacs. Obviously these cases are of prime importance to our understanding of the phenomenon as they provide the only direct knowledge we have of the subjective accounts of the experience of hypoxia and the motivations for inducing it in this fashion. Unfortunately most of these living cases are reported very sketchily.

The behaviors described by survivors closely resemble those that have died using them. Most have used self-hanging but suffocation and self-drowning have also been described. In most cases it appears to have begun around puberty though sometimes an inordinate interest in ropes, chains etc is reported from childhood. Often the onset is obscure though some reports suggest imitation of others may play a part in some cases.

The living cases reported in the literature usually, though not always, have been referred to mental health professionals for various reasons. Among the fifteen cases that I have examined over my career, all were suffering or had suffered from concurrent mood and anxiety disorders. Eight of them had made suicide attempts in the past. Unlike most of those reported in the literature the commonest method used to induce hypoxia in my own cases was some form of suffocation, usually with an plastic bag, but several methods were often used in combination.

Although none of my cases reported using hypoxyphilia on a daily basis many did so very frequently and had performed the act numerous times in the past without fatal mishap.

Eight of my patients performed their ritual in the nude and three cross-dressed. A wide range of sexual paraphernalia was also used including mirrors, self-photography, bondage, hoods, blindfolds, enemas, electrical stimulation and beating themselves or by a partner. Only two of them viewed pornography during their activities.

As with fatal cases, the living patients reported a wide range of concurrent paraphilias including other forms of masochism, sadism, transvestitic fetishism and fetishism.

Many of these patients were articulate and willing to discuss their thoughts, fantasies and motivations in great detail. Surprisingly perhaps, half of them described frankly sadistic fantasies. None of them sought the effects of hypoxia as such but usually reported that their activities were part of a more elaborate, usually masochistic, fantasy in which they were forced into painful, uncomfortable or humiliating situations. Three had cross gender fantasies and three clearly described being sexually aroused by being in physical danger and of struggling against physical restraints.

What is striking about the accounts of living practitioners is that they reflect a very different picture from that gained from the study of fatal cases. While the high frequency of mood disorder might be dismissed simply as the reason why these patients presented to a psychiatrist, a number were referred because of the hypoxyphilic behavior itself and out of concern they were endangering their lives. Some other authors who have studied living cases have been struck by the "death orientation" and have suggested, on psychodynamic grounds, that hypoxyphilia is a "suicidal syndrome." However, as noted above most authorities now regard hypoxyphilic fatalities as presumptive accidents and one might consider them more akin to the unintended deaths of those who hang-glide, sky-dive, climb high mountains or engage in other hazardous pursuits.

The association with mood disorders is intriguing also because of the increased awareness of the frequency of these disorders seen in other paraphilias, including those that are not illegal. Moreover, the "thrill seeking" characteristics of many man with sexually compulsive behaviors has often been observed.

It is of interest that, among fatalities, self-hanging is the commonest method used but, among living cases, suffocation is the commonest. Similarly fatal cases more likely employed complex apparatus. At the time of writing only one of my fifteen living subjects appears to have died by hypoxyphilia suggesting, perhaps, that self-hanging and the use of complicated equipment, are more likely to result in eventual fatality. This may be important as it may be possible to counsel a hypoxyphiliac to chose the apparently less risky method.

This leads to the obvious consideration of treatment options for hypoxyphilia. Here my experience has been that, as with other paraphilias, few are really motivated to give up their means of sexual gratification. For the few that can be engaged, the combination of cognitive behavior therapy and medication would be recommended. With such a strong association between hypoxyphilia and mood disorder, an SSRI antidepressant will have a dual benefit of helping to relieve depression and reducing sexual impulsivity. I myself have also used anti-androgens and, in one case, castration, all with good outcomes followed, in one or two cases, over many years.

Finally, I want to return to the question that I introduced at the outset: Is "hypoxyphilia" the most appropriate term for this behaviour? It is not at all clear to me from the clinical material that the subjective experiences of hypoxia are, in themselves, what these individuals most desire. Their fantasies are, more typically, of being in danger, "on the edge," having one's life in the balance and at the mercy of impersonal forces, of defying death.

References and further information available on request from the author [email protected] by Mark G. Koetting, Ph.D. Sharper Future San Francisco, California

In 1991, Multi-Health Systems published the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R), a 20-item clinical rating scale designed to assess psychopathy, which Hare (1998) defined as a "socially devastating" personality disorder characterized by egocentricity, impulsivity, irresponsibility, shallow emotions, lack of empathy and remorse, chronic deception, and persistent violation of social norms. The PCL-R has been described as "state of the art" (Fulero, 1995), and "unparalleled" in its ability to predict violence (Salekin, Rogers, & Sewell, 1996), including sexual aggression. High scores may also be associated with negative treatment outcome (Rice, Harris, & Cormier, 1992) despite ostensibly positive treatment performance among sex offenders (Seto & Barbaree, 1999). Given the status of psychopathy as "one of the most crucial factors to consider" in the assessment and treatment of sex offenders (Seto & Lalumiere, 2000), the recent release of the 2nd Edition of the PCL-R is a significant event for many ATSA members.

In this review of the PCL-R, I will provide a summary of the changes from the 1991 PCL-R to its 2nd Edition, with mention of the nascent measure's strengths and weaknesses, and highlights of the data accumulated over the last 12 years pertaining to the PCL-R and its use with sex offenders.

To start with, the 2nd Edition uses the exact same items and verbatim scoring criteria as the 1991 PCL-R, which affords continuity with the extensive literature from the past decade. There are several strengths of the PCL-R: Prodigious data- The chapter addressing validity in the new manual is four times longer than the 1991 version, with a separate section dealing with the PCL-R and sexual recidivism (see below). The data presented in the manual are based on a total of nearly 11,000 individuals and 33 North American samples. Expanded norms- Descriptive and validation data are now available for specific groups, such as female and African-American offenders, British and Swedish samples, substance abusers, and rapists and child molesters. Clinical and Research Utility- The two factors of the PCL-R (F1=Interpersonal/Affective, F2=Social Deviance) are now subdivided into four "facets": F1 entails the facets labeled "Interpersonal" and "Affective" and F2 includes the facets labeled "Lifestyle" and "Antisocial." In conjunction with their corresponding T-scores (which have replaced the percentile ranks and are listed on the PCL-R score sheet), these six clusters (two factors, four facets) will permit finer clinical discriminations both between subjects and within a particular subject. The four facets should also ignite research into potential subtypes of psychopathy that may ultimately bear on treatment and recidivism. Controversial Issues- In the manual, Hare directly responds to various criticisms and arguments advanced by psychopathy researchers on several provocative topics (e.g., "white collar" psychopaths, adolescent psychopathy and early labeling, and psychopathy as a variant of normal personality). Hare also critiques Cooke and Michie's (2001) three-factor model of psychopathy - in which core personality traits are afforded more weight than antisocial behaviors - as consistent with "an academic view that is at odds with clinical tradition." However, this complex conceptual debate is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. Clarity- Perhaps in spite of its "technical" label, the manual is lucidly written, with an abundance of helpful tables. Clinical Interview- Questions in the Interview Guide are modified somewhat from the previous form, and more space is provided to record responses.

As with the 1991 version, there remain several shortcomings of the PCL-R, including its average length of time to administer and score (three hours or more), its requirement of detailed file information, the small percentage of Hispanic-American individuals in the normative samples (2.6%), and its susceptibility to faking good (see p.32 of the manual). In some cases, these weaknesses may warrant use of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (Lilienfeld & Andrews, 1996), a promising self- report measure of psychopathy that continues to garner research support. Of particular relevance to the reader, some useful and perhaps surprising data on sexual abusers is documented in the new PCL-R manual. Note that only about 20% of the PCL-R's normative sample of 1384 sex offenders were scored using the standard procedure. The remainder were scored based solely on file review, which reduces the total scores by about seven points (Hare, 2003). Therefore, Hare recommends using the norms for all male offenders when interpreting scores for sex offenders. About 33% of the 162 rapists and 66% of the individuals who committed both rape and child molest (mixed group) scored equal to or greater than 30, Hare's (1991) recommended cut score for a diagnosis of psychopathy. The standard procedure yielded mean scores of 25.5 for rapists, 20.9 for child molesters, and 29.0 for the mixed group.

Based on 11 studies of the PCL-R's use with adult sex offenders published between 1995 and 2003, several general conclusions can be drawn. The PCL-R is less strongly related to sexual recidivism (correlations typically range from .20 to .30) than it is to violent recidivism (correlations often equal .30 or higher) for sex offenders. Using a cut score of 25 on the PCL-R, the percentage of psychopathic sex offenders who commit a new violent offense is about twice that of non-psychopathic sex offenders. The mean PCL-R score of sex offenders who reoffend sexually is generally over 21, whereas the mean for non- recidivists is typically under 18. Finally, several recent studies have confirmed that sex offenders rated high on the PCL-R (using cut scores of 25, 26, and 30) who also show evidence of deviant sexual interests have sexual recidivism rates of 60% to 70%, about twice the rate of non-psychopathic, non-deviant comparison groups.

Like its predecessor, the 2nd Edition of the PCL-R is a utilitarian instrument with an impressive base of empirical support. For clinicians who are both trained in the use of the PCL-R (for information: www.hare.org) and who assess and treat sexual aggression on a regular basis, the PCL-R is an indispensable tool.

Psychological test available to qualified users from Multi-Health Systems www.mhs.com Books: 2003 In Review Reviewed by David Prescott, Forum Editor

Editor's note: If there is a common frustration for myself, authors, and readers, it is that there is a limit to how many books can be reviewed in each issue. In many cases, it can be difficult for members to contribute reviews, and our best reviewers are often busy contributing to ATSA in other ways. In this article, I include a number of smaller reviews of recent books in the hopes that members may better choose among them.

In Their Shoes: Examining the Issue of Empathy and Its Place in the Treatment of Offenders

Challenging Experience: An Experiential Approach to the Treatment of Serious Offenders

Child Maltreatment Risk Assessments: An Evaluation Guide

Denial and Discovery: Behind the Scenes of Psychosexual Assessments

How to Work with Sex Offenders: A Handbook for Criminal Justice, Human Service, and Mental Health Professionals

In Their Shoes: Examining the Issue of Empathy and Its Place in the Treatment of Offenders Edited by Yolanda Fernandez, Ph.D. Wood'n'Barnes, 2002 (www.woodnbarnes.com ) $27.95 USD, 195 pages

Anyone who has ever argued with a loved knows that empathy is a dynamic aspect of humanity that can ebb and flow without apparent reason. Those entering the field of sexual abuse are quickly told that empathy is a key element in treating this population, and yet recent research demonstrates little correlation between empathy and recidivism (e.g. Hanson & Bussiere, 1998). Worse still, most of this research indicates that we have a long way to go in properly defining and measuring this elusive construct.

Fernandez and her colleagues have produced a volume of depth and breadth that will interest practitioners, students, and researchers alike. It is likely the first and most extensive volume of its kind on the subject. Its scope ranges from Geris Serran's exhaustive overview of attempts to measure empathy to Ruth Mann, Maxine Daniels, and William Marshall's hands-on discussion of role play in empathy development. Perhaps most importantly, Fernandez and her colleagues place strong emphasis on the importance of empathy in treatment providers, and provide a "Criteria for Therapist Assessment" checklist as an appendix.

William Marshall provides an introductory chapter on the "historical foundations and current conceptualizations of empathy", that addresses such controversial areas as trait/state views of empathy, and its distinction from sympathy. He further discusses his multi-stage model of empathy, along with its weaknesses. Liam Marshall provides a chapter describing the development of empathy in individuals from a human evolutionary perspective. It discusses affective interpersonal responses, gender differences, and attachment, with potential application to abusers of all ages. Dana Anderson and Philip Dodgson provide a chapter on "empathy deficits, self-esteem, and cognitive distortions in sexual offenders" which considers many of the finer points of empathy development. Among their points is an observation that changes in one's emotional vocabulary do not always result in the important changes in thinking and behavior that reduces the risk of harmful behavior. They also refer to William Marshall's observation that in some cases, the affective response to another's situation can itself be so upsetting that the observer will respond by relieving their own distress, thereby appearing unempathic. Beyond mere academic discussion, the authors stress the importance of self-esteem in the development of empathy and the reduction of cognitive distortions that drive re-offense. Other chapters include Heather Moulden and William Marshall's discussion of "empathy, social intelligence, and aggressive behavior" and Geris Serran's "emotional expression and recognition". The book's broad scope ensures that readers will find some chapters of greater relevance to their work than others.

Given our field's history of difficulty in defining empathy and understanding its relationship to sexual recidivism, this book is both timely and useful. As we come to better understand the active ingredients of treatment (e.g. thoughts, behaviors), In Their Shoes will no doubt contribute significantly to our attempts to help abusers better access their treatment. While empathy, self-esteem, and integrity may not yet show up in the research, Fernandez and her colleagues clearly demonstrate that our attention to empathy can result in better treatment outcomes and better hope for those affected by sexual abuse.

Challenging Experience: An Experiential Approach to the Treatment of Serious Offenders by John Bergman, MA, RDT, MT-BCT and Saul Hewish, Dip CC. Wood'n'Barnes, 2002 (www.woodnbarnes.com ) $27.95 USD, 160 pages

One need not look far to find controversial elements of experiential treatment with sexual offenders. Critics describe it as intrusive, traumatizing, and without empirical support. Others express concerns around training, its potential for misuse, and their own discomfort. Bergman and Hewish address many of these concerns from the start.

While not intended to be a complete volume on every facet of experiential treatment, the authors have compiled an excellent set of exercises that move from simple warm-ups, through low- to high-intensity treatment. Strategies for designing sessions are provided. Those practitioners in settings where high intensity experiential treatment might not be warranted will still find many fresh ideas for moving closer to substantive issues in treatment.

Bergman and Hewish emphasize a number of critical elements at the outset. These include using the exercises only within a strong therapeutic relationship, and following some basic rules of role-play. Safety and simplicity are fundamental values that are emphasized throughout the text. The authors point to many underlying theories very succinctly, while outlining a number of areas where practitioners will wish to be knowledgeable before fully using this book. Far from complicated or convoluted, the exercises seem almost deceptively easy, and will be beneficial to those attempting to access the affective aspects of treatment, exit from power struggles, or get past old beliefs.

Challenging Experience plainly reflects the years of work the authors have invested in this treatment. Each aspect is honed down to its most basic elements. Overcoming doubt and resistance, for example, is expressed with confidence and simplicity: "The client only needs to see the conflict clearly. He needs to know that it is between him and his 'this is stupid'. He will do the solving .We use these techniques to be 'in the now' where clients can solve problems just as we do, 'in the now'" (p.6).

The reader will wish to keep in mind that the exercises contained in this book can be very powerful tools that require careful use. However, just as they can move clients who are stuck at one place in treatment, they can also move stuck therapists. Despite the book's simplicity, it is never reductionist, and can stand on its own or as a springboard to more advanced study. Child Maltreatment Risk Assessments: An Evaluation Guide by Sue Righthand, Ph.D., Bruce Kerr, Ph.D., and Kerry Drach, Ph.D. Haworth Press, 2003 (www.haworthpress.com ) $24.95 USD, 216 pages

Those familiar with Dr. Righthand's contributions to the JSOAP, JSOAP - II, and OJJDP bulletin "Juveniles Who Have Sexually Offended" will already be aware of her diligence and thorough understanding of the field. For this book, she has teamed up with two other experts in forensic evaluation to produce a document essential to those assessing and preventing child abuse. Its focus on the origins of child maltreatment and developing risk management strategies makes it invaluable to ATSA members working with families and their reunification.

Righthand, Kerr, and Drach describe risk assessment as a process of "identifying factors that research has found may increase or mitigate risk. One objective of risk assessment is to identify the risk of future child maltreatment that individuals or families present. Another objective is to design interventions for effectively managing risk" (p.83). After an introductory chapter outlining recent research into the effects of child abuse and neglect, the authors review the literature around numerous etiological factors, including discussion around recent investigation into the helpful effects of safety plan implementation. A chapter on "formulating risk management strategies" includes an overview of treatment outcome literature. As ATSA members might expect, cognitive-behavioral interventions appear to be more effective than psychodynamic ones, and attention is given to treatment dosage and intensity. There is further discussion of matching parenting training with appropriate supportive services, and various abuse-specific interventions for family and child. Throughout their discussion, the authors stress that child maltreatment and its effects are "interactive processes involving both person-specific factors, such as individual competence, and situational variables" (p.166).

The final chapter, entitled "Putting It All Together" is a comprehensive overview of the process, and will interest all who are asked to describe risk. An extensive review of risk factors, ranging from historical and developmental, through personal and dispositional, to current contextual factors, is provided, along with discussion of core questions for practitioners to ask. These include considerations of the persistence of risk factors across time and situation, factors that mitigate as well as increase risk, and the extent to which risk factors can be remedied or managed. The chapter concludes with a section on "conducting and writing quality evaluations".

Although written specifically for child maltreatment situations, Righthand and her colleagues offer overviews and advice that will benefit virtually any ATSA member. It is comprehensive, emphasizes diverse considerations, and borrows from numerous areas of study. For evaluators interested in expanding or sharpening their skills, this book will provide many possible avenues for further investigation and inquiry.

Denial and Discovery: Behind the Scenes of Psychosexual Assessments by Keith E. Anderson, LCSW, and Philip M. Smith, BA Trafford Publishing, 2002 (www.trafford.com ) $24.50 USD, 305 pages

Anderson and Smith have created a unique book. It is a collection of ten case histories taken from their practice in Saco, Maine. The authors made significant alterations to identifying data to protect confidentiality, often fusing multiple features from several cases. It is not written as a "how-to" textbook nearly so much as reflections on the assessment process and the lives of those with whom they work. From the first pages it is clear that the authors view the entirety of their work, from evaluating adults and juveniles, to building a practice, to writing the book itself as an ongoing journey uncovering not just fact, but a broader sense of the truth.

To those of us who take note of the work of others as a means of improving our own skills, this book will be a welcome addition. It is informal, inquisitive, and easy to read. The authors stance appears quite humanitarian, and a respect for each client, from the initial "denial" to the ongoing "discovery" (hence the title) is evident throughout. The authors work together on each evaluation using their individual attributes to complement each other as well as connect with a wider range of clients. It is written for a general audience as well as professionals. Each chapter is a narrative exploring the background, information gathering, and clinical interview of an individual, and each ends with a section on the "concepts and principles illustrated by the case". Although the authors use diverse test batteries based on individual case situation, they are not described to any great extent. The clinical interview is the primary focus.

Clearly, the assessment process is dependent on numerous factors, including each area's applicable legal framework, purpose for evaluation, referral sources, questions, and concerns, etc. Readers will likely find aspects with which they both resonate and disagree. In the end, the efforts of the authors to shed light on the most personal elements of interviewing and assessment, make this book both courageous and worthwhile.

How to Work with Sex Offenders: A Handbook for Criminal Justice, Human Service, and Mental Health Professionals by Rudy Flora, LCSW, ACSW Haworth Press (www.haworthpress.com) $22.95 USD, 252 pages (softcover),

An inherent danger in crafting an introductory handbook is that attempts to cover every aspect of our work can do considerable disservice to its more sensitive elements. Examples include family reunification, therapeutic engagement, or diagnostic thresholds for sexual disorders. A number of recent efforts (e.g. Carich and Mussack, 2001) have been quite impressive. Mr. Flora's book will benefit some who enter the field. However, it also omits a number of crucial developments in the field.

Flora, a practitioner and former probation officer, appears well aware of the need for a handbook that can assist law enforcement officials develop an introductory understanding of this population. As its title suggests, however, he covers a broad range of areas without noting the high level of training that each requires. For example, the chapter on family addresses only the generic work of Salvador Minuchin, and, more specifically, the work of Chloe Madanes.

Those working in reunification situations are familiar with the complexity of the task. Myriad abusive elements of family interactions can remain hidden unless practitioners specifically take them into account. The contributions of such authors as Jan Hindman, Anna Salter, Jill Levenson and John Morin, and Jerry Thomas all go without acknowledgement or discussion. Flora endorses through its inclusion such steps as having the abuser apologize on his knees, without taking into account the many conditions under which this would be completely inappropriate. His emphasis on apology appears to preclude an emphasis on taking responsibility. As many have observed, apologies can create an expectation that they be accepted. The chapter neither addresses the impact of abuse on child victims, nor advocates further training.

Other areas where further discussion would have been helpful include the brief section on risk assessment (pp 222-3), which mentions the VASOR and RRASOR, but not the Static 99, SONAR, MnSOST - R, VRAG/SORAG, or other scales and methods. A section on recidivism notes the 13.4% rate found in the Hanson and Bussiere (1998) meta-analysis, but does not discuss other elements such as rapist/child molester breakdowns or recidivism across time at risk.

Although antisocial personality disorder is referenced (pp 197-8), psychopathy is not. The research and writings of Vernon Quinsey, Robert Hare, Marnie Rice, Steven Hart, Grant Harris, Chris Webster and others are not mentioned. Similarly, the section on "standards in treatment" (pp 50-54) borrows heavily from the work of Eli Coleman and his colleagues, but never mentions ATSA's standards. While no author is obligated to mention ATSA or the work of its members, these omissions seem curious.

Flora's work is not without reference to the sex offender literature, and is not without merit. The introductory chapters can provide information to those looking to flesh out their interview schedules. However, sections such as "profiling sex offenders" (pp 20-22) risk leaving the uninitiated with a false sense of confidence. While the title implies that there is a clearly defined, well-demonstrated "right way" and "wrong way" to "work with " sexual abusers, this book falls well short of its implication that it can teach others how to work with this complicated population, their families, and victims.

References for all reviews available from [email protected] upon request. Members: Elizabeth Letourneau, Ph.D. (chair), Fred Berlin, M.D. Sandy Jung (student representative) Rebecca Palmer, M.S. Jim Worling, Ph.D.

The composition of the Ethics Committee is changing. Dr. Fred Berlin served diligently for the past two years and has rotated off the committee. Our sincere thanks to Dr. Berlin! I served on the committee for the past three years, and as Chair for the past two years and will rotate off in January. Fortunately, Dr. Jill Levenson (ATSA's Southern Regional Representative) will take over as Chair, and I have no doubt the committee will benefit from her leadership.

Recently, I reviewed each of the cases the Committee addressed over the past three years. It was with surprise that I counted only 12 formal complaints filed during that time. Of these, only three ended with recommended sanctions for findings of unethical behavior. Certainly, the actual rate of ethics violations is higher than this figure represents. Many violations are never reported and (generally) only complaints from current organization members are accepted. Nevertheless, these numbers suggest that, by and large, ATSA members go about their business with an appropriate degree of professionalism.

Two of the most difficult cases that were addressed during my tenure dealt with behavior as an expert witness. One of these resulted in sanctions (the member was found to have fabricated information use to qualify as an expert) and one case was dismissed. In this second case, a non-member sent in a complaint regarding guilt-phase expert testimony. Per the ATSA Advisory Board, the ATSA Executive Board, and the Ethics Committee's interpretation of the current (2001) ATSA Standards (particularly Standards 9.02 and 9.03), guilt-phase testimony is permissible. However, experts who testify must make clear the fact that testing results in no way indicate guilt or innocence. I would like to remind ATSA members that the Standards are currently under revision. ATSA members are encouraged to contact Professional Issues Chair Maia Christopher [email protected] or Co-Chair Bill Murphy [email protected] with suggestions regarding revision (or not) of these and other Standards.

Short- and Long-Term Committee Goals: 1. Continue discussion about a members-only hotline for informal ethics requests (as Chair, I fielded approximately one call per month requesting informal ethics consultation). 2. Improve the consistency with which ethics-related columns are submitted to the Forum. 3. Continue to ensure that ethics-related issues are included at the annual Conference. 4. Continue to work with the Standards & Procedures committee on revision of standards that have implications for the Ethics Committee.

Elizabeth Letourneau, Ph.D. Chair, Ethics Committee In recognition of those who have made significant contributions to the field of sexual abuse, the Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers is pleased to acknowledge individuals whose work and mission has impacted those affected by sexual abuse.

The Significant Achievement Award recognizes individuals who have contributed to the state of knowledge the field of sexual abuse; the reduction or prevention of sexual abuse; or the development of initiatives or programs to assist abusers or victim/survivors.

The Distinguished Practitioner Award recognizes an individual who, in their role as full-time clinician, has demonstrated excellent and innovative clinical skills that have engaged clients in the process of change and advanced the state of sex offender treatment.

The Public Education Award recognizes work by a journalist from the press, television, or film that has advanced the public understanding of relevant issues regarding sexual abuse and offending, as well as the role of effective treatment in risk management.

The Distinguished Contributions to Community Service Award recognizes an individual who has made outstanding contributions in serving the community through dedicating their time, energy, knowledge and skills to support/facilitate community safety and abuse prevention.

The Fay Honey Knopp Award is presented to a person studying, working or volunteering in the field of sexual abuser treatment or sexual abuse research whose work exemplifies the qualities and vision of human goodness that Honey brought to the field and whose work/spirit is an inspiration to others.

The ATSA Awards are not necessarily awarded annually. Each year the recipients will be chosen based on the number of and quality of submissions.

A complete description of the awards, the criteria and the nomination procedure can be accessed by going to the ATSA website www.atsa.com and clicking on Awards and Grants in the left hand navigation bar. Rediscovering and Utilizing The Concept of The Unconscious in Contemporary Sex Offender Treatment

By Mark S. Carich, Ph.D. Psychologist Administrator for the Illinois Department of Corrections' Big Muddy Correctional Center.

Carole Metzger, L.C.S.W. Unit Supervisor Public Service Administrator at Cheshire Mental Health, Illinois Department of Human Services

Introduction It seems that much of contemporary sex offender treatment is based on utilizing conscious oriented theory and therapy techniques. Alone, unconsciously depth-analytically oriented therapies in general have proven to be ineffective with chronic and more psychopathic offenders. Thus, clinicians have remained distant from utilizing the unconscious. Recently, Ward & Hudson (2000) have acknowledged the possibility of unconscious dynamics and processes involved in offending in their theoretical discussion implicit planning of sexual offending pathways. Our clinical experience indicates that there are effective unconsciously oriented techniques.

The purpose of this discussion is to define the unconscious and provide links to contemporary treatment.

What is the Unconscious? The unconscious is not a mystical concept that entails magic. The unconscious part of self is generally thought to be right hemispheric functioning of the brain (Lankton and Lankton, 1983). Everyone has right brain functioning. People operate out of the unconscious most of the time. The concept of the unconscious can be defined as, a hypothetical construct used to describe behavior, phenomena, stored material, processes, etc., out of immediate awareness (Carich, 1994a, 2001). Freud used a structural concept to denote the various levels and processes within levels (i.e., conscious, preconscious, and unconscious). He also viewed the unconscious as a negative entity. In contrast, Milton H. Erickson described the unconscious as a positive reservoir of learnings and experiences. He included: a reservoir of memories associations; patterned behaviors; trance states and behaviors; dissociative behaviors; altered states of awareness; involuntary ideomotor/ideodynamic behaviors; intuition; dissociation (sense of detachment); catalepsy (muscular immobility, rigidity and suspension of limb movement); rhythmic patterns; imagery/images; time distortion; creativity (artistic patterns); amnesia; symbolic representations; non-verbal behavior; spontaneity (automatic thoughts and responses, flash fantasies); bio-physiological responses; spatial modes (Erickson, Rossi & Rossi, 1976; Havens, 1985). Another colleague of Erickson, E.L. Rossi (1993), emphasized a specific location of the unconscious in the hypothalamic and limbic system of the brain. He views this as the mind-body connection via state dependent memory and learning. Consciousness ranges from immediate to unconscious awareness.

In our experience, conscious and unconscious awareness forms a complementary whole and the conscious can't exist alone (Ansbacher and Ansbacher, 1956; Ansbacher, 1982; Carich, 1994a, 1996b). We view the unconscious as both a psycho- physiological entity and process. It is a reserve of resources processing dynamics and memory.

The Sex Offender and the Unconscious Many sex offenders appear highly dissociative and exhibit the above behaviors. Although Erickson viewed the unconscious as a positive constructive factor (force), we have found that the unconscious can be a source of deviancy, distortion and destructiveness depending on the individual. Highly deviant people use the unconscious as a source of deviancy. Most offenders have both positive unconscious resources, along with deviant templates. Deviant templates are considered offense scripts, that include implicit decision processes (Ward & Hudson, 2000). According to Ward & Hudson (2000), offenders use mental simulation (imagery) and automatic processes. The offending cycle is deeply ingrained into the unconscious, as offenders make deviant choices at unconscious levels. Most chronic and psychopathic offenders operate from distorted world views (ingrained templates) out of immediate awareness. Offense scripts are developed through repeated learnings and decisions over time in which offending behaviors are encoded into long-term memory. Offense scripts could be encoded in state dependent memory, learning and behavioral processes, as previously discussed by Carich & Parwitaker (1992). Ward & Hudson (2000, p. 191) define automatic processes as past, relatively autonomous, unintentional, difficult to consciously control and effortless (fast, coherent, and consistent) and may occur without conscious awareness... Offense scripts are templates (or unconscious structures and implicit rules) that guide behavior. These implicit rules consist of beliefs and decisions made at unconscious levels.

Applications It appears that the most effective psychotherapy and/or treatment involves knowingly or unknowingly using the unconscious process. By viewing conscious awareness on a continuum, it lends itself to a number of applications. Some of these include: imagery; guided imagery; metaphorical therapy; trancework/hypnotherapy; strategic tactics; dreamwork; mind-body approaches; relaxation protocols; art therapy; systemic interventions; psychodrama; etc. (Carich, 1999; Carich & Patrick, 1994; Carich & Metzger, 1999a, 1999b, 1999c). The essence of long term therapeutic success involves altering deviant templates and mobilizing positive resources to replace deviant templates.

Conclusion The unconscious construct has been downplayed and neglected in contemporary sex offender treatment. Paradoxically, most effective conscious-oriented approaches appear to be operating at unconscious levels within the offender and group process. Our position is best summarized by Ward & Hudson (2000, p. 199): Individuals can act out without being aware of their underlying intentions in many facets of their lives. Just as much of everyday behavior is unconscious, parts of the offending process remains unconscious.

In terms of contemporary theory, Ward & Hudson (2000) have begun using the concept in redefining the theories of RP and pathways to offending. Instead of denying or underplaying the unconscious process, the real question centers around utilizing and accessing those processes. The key is finding and accessing various windows into the offenders unconscious process. In conclusion, Honey Fay Knopp (1994) emphasized building bridges between disciplines. One such bridge is recognition and utilization of the unconscious process construct within the contemporary sex offender treatment framework.

References are available upon request from the authors at [email protected] or the Editor at [email protected] The following members were approved in September, 2003 and January 2004.

Mzola Ahuama-Jonas Tracy DeTomasi Christine D. Hendy Decatur, GA Mundelein, IL Kissimmee, FL

Jennifer Anderson Philip Dodgson A. Elissa Hilyard Mundelein, IL Aurora, Ontario Lawrence, KS

Armand M. Belmonte Theresa M. Donsbach Sharon C. Hinze Waterbury, CT Arcadia, FL Spokane, WA

Larry J. Benoit Roger Dowty Robert F. Hirsch Lafayette, LA Missoula, MT Seattle, WA

Lisa Brochu Kerry Jo Duty Elizabeth Horrillo Las Vegas, NV Ann Arbor, MI Roseville, CA

E. Douglass Brown Gary M. Echt Steven R. Jenkins Phoenix, AZ Pepper Pike, OH San Bernardino, CA

William B. Brown Amanda Fanniff Robert E. Jesiolowski Lake Saint Louis, MO Tucson, AZ Indianapolis, IN

Margaret Bullens Leslie A. Fiferman Phillip Karpinski San Diego, CA Rapid City, SD Las Vegas, NV

La Teisha Mason Callender Kimberly A. Finch Hugh Keating Monroe Township, NJ Mauston, WI Kingman, AZ

Tiffany Caram Lyle B. Forehand Thomas Kiester Shawnee, OK Big Bear Lake, CA Los Angeles, CA

Lisa H. Carr Richard L. Frank William R. Kraus Oregon City, OR Inverness, FL Marietta, GA

Craig L. Christensen Kathy L. Gelein Angelica Lacalamita Erie, PA Roseville, CA Mundelein, IL

Dana Costin Danielle A. Harris Brannon LaForce Toronto, Ontario College Park, MD Mobile, AL

Brian Cunningham Linda C. Hatzenbuehler Lisa Lynne Layne Patton, CA Pocatello, ID Kansas City, MO

Andrea L. Dalton Ainslie Heasman John A. Leibold Mississauga, Ontario Fresno, CA Erie, PA Francita Love Laura M. Pries Brent Thibault Decatur, GA Bowling Green, OH Barre, MA

Heidi Marcon Joseph W. Proctor Suzanna M. Tillotson Toronto, Ontario Oregon, IL Murray, UT

Carmen B. McCoy Amy Raff Damian S. Vallelonga Michigan City, IN Ann Arbor, MI Syracuse, NY

Stephen J. McGovern Norbert Ralph Terrie Velasquez Mauston, WI Pleasant Hill, CA Reno, NV

Deon Mehring Julio A. Ramirez Victor Velonis Minot, ND Phoenix, AZ Palm Beach Gardens, FL

Donna L. Moore Jennifer Schneider Jonathan Venn Nashville, TN Newark, NJ Columbia, SC

Julie A. Motley Wanda Schofield Brent E. Wainwright Farmington, MO Waterville, Nova Scotia Sandy, UT

Norman G. Nelson Betty Lou Schroeder David A. Wallace Lynnwood, WA San Antonio, TX Albany, NY

Charles I. Newell Char Schultz Sam L. Wallace Billings, MT Napa, CA Fayetteville, AR

Sarah Noakes Kyle W. Shore Richard Weinberger Victoria, Australia Indianapolis, IN Minneapolis, MN

Mark Nowicki Dominique Simons Keef Weinstein Kihei, HI Colorado Springs, CO Mundelein, IL

Leslie Offenbach Kaffie Sledge Mindy White Hartford, CT Columbus, GA Arcadia, FL

Melissa J. Olsen Ashley Smith Colleen Wilson Iowa City, IA New Orleans, LA Mount Pleasant, MI

Cameron Page Gary Smith Mark D. Wolkenhauer San Bernardino, CA Marysville, WA Patton, CA

James J. Park Clint Sperle C.D. Wright Chico, CA Sioux Falls, SD Winston-Salem, NC

Byron Parks Vicki R. Stancu Kristen Zgoba Reno, NV Pearl City, HI Newark, NJ

Cindy Peterson Nancy Mumma Streit Winona, MN Little Rock, AK

Ann Pimental Paul J. Sturmer Bridgewater, MA Bangor, ME We have good news-the ATSA Practice Standards and Guidelines have not gone South for the winter. As you know, the Professional Issues Committee has been revising the Standards document. The Committee has completed a draft that is available for review on the "Members Only" section of the ATSA home website (www.atsa.com). Comments and feedback will be accepted until February 3, 2004.

We believe it is important that every opportunity be provided for member involvement at all levels of the Standards revision process. The full membership has another opportunity to provide the Professional Issues Committee guidance and assistance in the final development of the ATSA Standards and Guidelines.

Thank you to everyone who has given us input and we look forward to hearing from more of you.

Maia Christopher Bill Murphy Co-chair, Professional Issues Committee Co-chair, Professional Issues Committee Access proposal form on ATSA website: http://www.atsa.com/confOther.html

Direct contact: Conference Administrator NOTA PO Box 28259 Edinburgh EH9 1YQ [email protected] Telephone/Fax: 0131 466 0139

Closing Date for Submissiohns: 1st March 2004