The Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Vuyelwa Kuuya

1 A consequence of the chaos and instability caused by the Second Congo War was the widespread illegal exploitation of minerals and resources in that nation. The war took place between August 1998 and July 2003. It was the largest war in modern African history and directly involved 8 African nations, as well as about 25 armed groups. In April 2001, the UN appointed a Panel of Experts to investigate the illegal exploitation of diamonds, coltan, gold and other resources in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The reports of the Panel accused Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe and a number of individuals as well as corporations of systematically exploiting the resources of the DRC. 2 The UN Expert Panel accused some corporations of being linked to the activities of rebel groups within the DRC. These groups were said to be directly involved in the illegal exploitation and plundering of the natural resources of the DRC. This paper analyses the Panel’s findings on the role of corporations in the conflict. It also provides an evaluation of the manner in which the Panel carried out its mandate. It focuses on the allegations against companies that formed relationships with a particular group, the Rassemblement Congolaise pour la Democratice (Rally for Congolese Democracy), (“RCD”), a Rwandan rebel group which was accused by the Panel of being one of the principal perpetrators of many human rights abuses. The paper also focuses on corporations that allegedly formed relationships with individuals who were found by the Panel to have aided the conflict. 3 The Panel reached the conclusion that “The role of the private sector in the exploitation of natural resources and the continuation of the war has been vital. A number of companies have been involved and have fuelled the war directly, trading arms for natural resources, which are used to purchase weapons. Others have facilitated access to financial resources, which are used to purchase weapons. Companies trading minerals, which the Panel considered to be ‘the engine of the conflict in the DRC’, have prepared the field for illegal mining activities in the country.”1 This paper will asses these and other such findings made by the Panel.

The Expert Panel Reports on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth in the Democratic Republic of Congo (the Panel). 4 The Panel was commissioned with the mandate: “ To follow up on reports and collect information on all activities of illegal exploitation of natural resources and other forms of wealth in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, including violation of the sovereignty of that country;

Prepared by Vuyelwa Kuuya, Research Fellow– Lauterpacht Centre for International Law, University of Cambridge; Research Associate- First Africa (Pty) Ltd. 1 UN Expert DRC Panel Report S/2001/357 dated 12 April 2001 (para 215).

1 ‘To research and analyse the links between the exploitation of the natural resources and other forms of wealth of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the continuation of the conflict; ‘To revert to the Council with recommendations.” 2 In addition, the Panel interpreted its mandate to include a special focus on the role of corporations and individuals in fuelling the DRC conflict. 3 5 The Panel, which was a non-judicial body, subjected the facts it uncovered to a ‘reasonable standard of proof’.4 As will be discussed later, the ambiguity of this phrase caused confusion amongst companies. This phrase led the Panel to make inflammatory allegations against corporations in the 5 reports and 1 addendum it authored.5 The making of these allegations left the Panel open to accusations of abuse of ‘company human rights’ by aggrieved corporations, who were uncertain of the legality and legitimacy of the accusations levelled against them, and whose reputations were damaged. 6 The Panel travelled throughout the DRC and to other involved and affected countries within Africa and elsewhere. It conducted interviews with, and collected oral testimony from, inter alia individuals, companies, government officials, representatives of states including presidents, representatives of the United Nations, international organisations and armed groups. Testimony by witnesses was given on a voluntary basis and the identity of witnesses was kept anonymous. The Panel also analysed documentation.

Illegality 7 According to the Panel, there were four instances of illegality that could be identified in the context of the illegal exploitation of natural resources and other forms of wealth in the DRC. i. Firstly, activities were defined as illegal if they occurred without the consent of the Government of the DRC. ii. The second instance of illegality related to action which went against the existing regulatory framework of the DRC. In this context “the carrying out of an activity in violation of an existing body of regulations”6 was deemed to be an “infringement of the law and considered illegal or unlawful”7 iii. Thirdly, activities that were carried out without regard to “widely accepted practices of trade and business” were also considered illegal. iv. Lastly, the violation of international law, including soft law was also taken to be illegal. Again, the Panel did not provide the content of this body of law. The Panel did not define “soft” law. In the international context, it ‘refers to principles and policies which have been negotiated and agreed between states, or promulgated by international institutions, but which are not mandated by law or subject to any formal enforcement mechanisms. Soft law instruments are given a range of titles, typically,

2 S/2001/49, 16 January 2001, para 1. 3 Ibid., para 5. 4S/2003/1027, para 5. 5 S/2001/49 16 January 2001; S/2001/357 12 April 2001; S/2001/1072 13 November 2001; S/2002/565 22 May 2002; S/2002/1146 16 October 2002; S/2002/1146/Add.1 S/2003/1027 23 October 2003. 6 UN Expert DRC Panel Report S/2001/357, 12 April 2001, para 15. 7 Ibid.

2 “codes of practice”, “guidelines’’ “recommendations” or “declarations”, but, whatever the terminology, the crucial distinction between a “soft law’ instrument and a treaty is that compliance with the former is ‘voluntary’ (at least in the legal sense.)”8 Examples of ‘soft law’ instruments that would have been applicable in the DRC at the time of the conflict are listed in Appendix 1. Exploitation 8 The Panel defined exploitation as “ all activities that enable actors and stakeholders to engage in business in first, secondary and tertiary sectors in relation to the natural resources and other forms of wealth of the Democratic Republic of Congo.”9 9 This broad interpretation enabled the Panel to focus on “extraction, production, commercialization and exports of natural resources and other services such as transport and financial transactions.”10 Natural resources and other forms of wealth of the DRC. 10 These were taken to consist of: a. “mineral resources, primarily coltan, diamonds, gold and cassiterite (a tin oxide mineral and the chief ore of tin); b. agricultural produce, forests and wildlife, including timber, coffee and ivory; and c. financial products, mainly in regard to taxes.”11

The role of corporations in sustaining the conflict 11 The Panel found that there were several “elite networks” that operated in the DRC. These were defined as “politically and economically powerful groups involved in exploitation activities which are highly criminalised”.12 The Panel advanced the view that businesses and corporations played a part in sustaining the DRC conflict and provided specific names of such companies. It alleged that corporations that had formed relationships with rebel or armed forces as well as with individuals were involved in fuelling the conflict. “ By contributing to the revenues of the elite networks, directly or indirectly, companies and individuals contribute to the ongoing conflict and to human rights abuses.”13 “The consequence of illegal exploitation has been…the emergence of illegal networks headed by either top military officers or businessmen. These …elements form the basis of the link between the exploitation of natural resources and the continuation of the conflict.” Companies and armed groups.

8 Zerk J. Multinational Enterprises and Corporate Social Responsibility (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2006) 69-70. 9 s/2001/357 (para 16). 10 Ibid. 11 Ibid.,(para 13). 12 S/2002/1146 (para 6). 13 UN Expert DRC Panel Report S/2002/1146 dated 16 October 2002 (para 175).

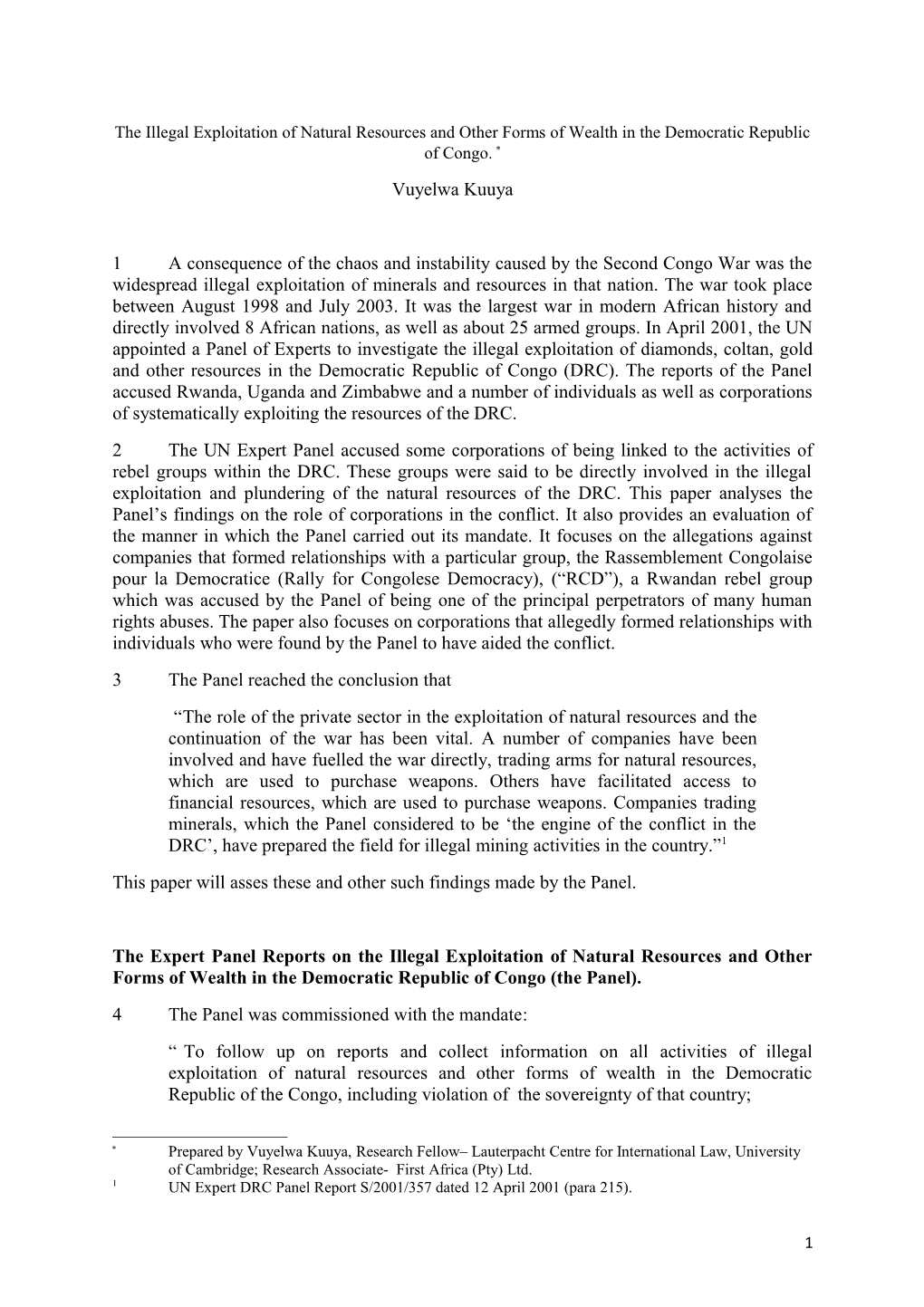

3 12 Some formed relationships with the Rassemblement Congolaise pour la Democratice (Rally for Congolese Democracy) or the RCD. The RCD This group consisted of between 2000 and 5000 combatants and was sponsored by Rwanda. During the war it was in effective control of most of the eastern DRC. It “assumed all the State administrative functions in the areas it holds.” The Panel stated that there was a “link between the exploitation of the resources and the on-going efforts of the RCD to continue the conflict, or at least to maintain the status quo.”14 The RCD was the principal perpetrators of several abusive practices in the DRC as is shown in Table 1 below.

Company Rebel group Alleged Activities of rebel group Link between company and rebel group Dara Forest 15 RCD Between September 1998 and DARA Forest Company obtained Timber Citi Bank16 The group held a August 1999, RCD forces concessions from the RCD. This Air Boyoma.17 monopoly over forcibly seized products and amounted to an illegal extraction of Coltan resources in resources from farms, storage timber because it occurred without the Goma area and facilities, factories and banks.’20 authorisation from the government of the received U$ 1 Between U$1-8 million DRC.28 million per month Congolese Francs were stolen by in taxes from the RCD from the Kisangani Citibank facilitated loan payments to mining companies Bank..21 RCD.29 in the area.18 Taxes Locals in Kisangani were were ‘aimed at murdered and injured when they A former first Vice-President of RCD was financing and tried to resist the looting of a shareholder in Air Boyoma. It supporting the war banks and seizure of other transported natural resources between effort.’19 resources by the group.22 Goma and Lodja.30 From 1998 the RCD forcibly removed 7 years of mineral resources from mines in Eastern Congo. It removed between 2000 and 3000 tonnes of Cassiterite, and between 1000 and 1500 tonnes of Coltan from the region.23 In 2000 the group killed 348 elephants in the Kahuzi-Biega Park. Rebels were found with 2 tonnes of elephant tusks in the Bakavu area. It also seized 3 tonnes of elephant tusks in Isiro.24 Child labour was utilised by the group in the Kilo Moto and Equateur provinces.25 14 S/2001/1072 (para 127). 15 Company received mining concessions from the RCD in eastern DRC. 16 S/2001/357 (para 132). Citibank also allegedly handled the finances of the AFDL rebel group led by Kabila. before his ascension to the presidency of the DRC Ibid (para 30). 17 The vice president of the RCD division in charge of the Goma region, was a shareholder in Air Boyoma. 18 Ibid., (para 145) 19 S/2001/357 13 (para 68). 20 Ibid., (para 32). 21 Ibid., (para 42). 22 Ibid. 23 S/2001/357 (para 33). 24 Ibid.,(para 61 and 62).

4 The group charged mining companies taxes on about 8 different minerals.26 The RCD group engaged in arms trading.27 Table 1 13 Table 2 below provides a list of other companies that were involved in activities that sustained the DRC conflict. This was done in various ways such as the payment of taxes to rebel forces who perpetrated human rights abuses, transportation of illegally exploited resources, failure to pay taxes to the authorities in the DRC, supplying arms and facilitating the trade in conflict resources. Table 2

Company Conflict sustaining activity Air Navette, 31 Transportation of arms to rebels and removal of Jumbo Safari minerals and other forms of wealth from the New Gomair DRC. Sun Air Services Kivi Air Services32 Air Cargo Ziare33 Sabena cargo34 They were a part of the ‘chain of exploitation SDV 35 and continuation of war.’36 Sabena Cargo was allegedly ‘transporting illegal natural resources extracted from the DRC’.37 Trinity This company removed gold and timber from the DRC without paying any taxes to the DRC authorities.38 33 companies from Germany, They were involved in the importation of Belgium, Rwanda, Malaysia, minerals from the DRC through Rwanda. 40 Tanzania, Switzerland, Russia, India, the United Kingdom, Netherlands and Pakistan.39 Avient Air Supplied services and equipment to the Zimbabwe Defence Forces.41 These forces

25 Ibid.,(para 69). 26 Ibid.,(para 144). 27 Ibid.,(para 145). 28 S/2001/357 (para’s 47 and 50). 29 S/2001/357 (para 132). 30 Ibid., (para 75). 31 S/2001/357 (para 31). 32 Ibid. 33 Annexure 1 of S/2002/1146. 34 S/2001/357 (para 76). 35 S/2001/357 38 (para 183). 36 Ibid., (para 182). 37 Ibid., (para 76). 38 Ibid., (para 80). 39 These companies were referred to in Annex 1 of S/2001/357. 40 Annex 1 of S/2001/357. 41 S/2002/1146 (para 55).

5 trained the FDD rebel group and supplied the group with arms. It also brokered the sale of 6 attack helicopters to the Kinshasa government.42 It also carried out bombing raids in the Eastern DRC in 1999 and 2000.43 Somikivu Operated in the eastern DRC and continued to pay taxes to rebels.44 Several individuals were instrumental in facilitating the exploitation of, and trade in, natural resources in the DRC. These individuals were listed in the final report of the Panel. The Panel suggested that the Security Council place a travel ban and financial restrictions on these individuals.45 Two of these individuals were Jean-Pierre Bemba who later became vice- President of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Aziza Kulsum Gulamali alleged to have been one of the most notorious arms traffickers in the region. The companies listed in Table 3 formed relationships with these individuals in various ways shown below. Table 3

Company Individual Alleged activities of the Alleged link between individual individual and company Air Navette46 Jean-Pierre Bemba.47 Unlawful seizure of Air Navette He was the leader of coffee beans from the transported the MLC insurgent Equateur Province.48 resources that group that perpetrated Seized 200 tons of coffee were seized by human rights abuses in from a coffee producing Bemba. the DRC. company.49 Instructed MLC insurgents to capture towns and forcibly empty banks of cash reserves.50 Produced counterfeit Congolese Francs which increased the rate of inflation in the DRC.51 Used child labour in the extraction of minerals.52

42 Ibid. 43 Ibid. 44 S/2001/1072 (para 71). 45 S/2002/1146 Annex II. 46 S/2001/357 (para 74). 47 He was the leader of the MLC insurgent group. 48 S/2002/1146 (para 53). 49 Ibid. 50 S/2002/1146 (para 40). 51 Ibid. 52 Op cit note 1 (para 58).

6 Sogem Ms Aziza Kulsum She paid approximately Sogem and Cogem53 Gulamali57 U$1 million to the RCD Cogem were Bank She allegedly rebel group per month.58 clients of Bruxelles provided arms to Hutu Gulamali.59 Lambert54 rebels and was alleged BankBruxelles Starck55 to have been one of Lambert handled Somigl56 the most notorious some of arms traffickers in the Gulamali’s Great Lakes region. finances. She was allegedly Somigl was a involved in the conglomerate of trafficking of ivory the RCD, and gold Gulamali was the General Manager of Somigl.

Joint venture companies Incentives for assistance 14 According to the Panel President Kabila “ wielded a highly personalised control over State resources, avoiding any semblance of transparency and accountability. Management control over public enterprise was virtually non-existent and deals granting concessions were made indiscriminately in order to generate quickly needed revenues and to satisfy the most pressing political or financial exigencies.”60 15 The Kabila regime “often used the potential of its vast resources in the Katanga and Kasai regions to secure the assistance of some allies or to cover some of the expenses that they might incur during their participation in the war. Among all of its allies, Zimbabwean companies and some decision makers have benefited most from this scheme…The most utilised scheme has been the creation of joint ventures.” 16 The Panel further stated that Kabila gave incentives in the form of mining concessions to Zimbabwean companies as a way of ensuring the continued support of Zimbabwean troops in the DRC’s war effort. It stated that: “ This scheme of giving incentives for assistance involved Zimbabwean companies receiving vast mining concessions, using their influence with the Kabila regime to develop joint ventures and receiving preferential treatment for their businesses”.61

53 S/2002/1146 (para 120). 54 This bank handled Gulamali’s finances Ibid., (Para 12). 55 S/2001/357 (para 92). 56 Ibid., (para 93). 57 Ibid. 58 S/2002/1146 (para 93). 59 S/2001/357 (para 92). 60 Ibid., (para 11). 61 Ibid., (para 158).

7 17 The Panel’s assessment was that the “richest and most readily exploitable of the publicly owned mineral assets of the DRC are being moved into joint ventures that are controlled by…private companies. These transactions, which are controlled through secret contracts and off-shore private companies amount to a million dollar corporate theft of the country’s mineral assets.”62 18 These joint ventures were formed as a result of the: “will of private citizens and businesses who endeavour to sustain the war for political, financial and other gains; for example, generals and other top officers in the Ugandan and Zimbabwean army and other top officials and unsavoury politicians in the government of the DRC.”63 This lack of transparency, accountability and order as well as this system of patronage, created the context in which Zimbabwean businesses formed joint ventures during the war. Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) 19 Zimbabwe’s official military force is referred to as the ZDF. The ZDF deployed troops to the DRC to assist Kabila in ejecting Rwandese, Ugandan and Burundian troops and rebels from the DRC. Within the ZDF was a division known as the Zimbabwe Defence Industries. Its main role was to take advantage of business opportunities on behalf of Zimbabwean military and government personnel. It formed various joint venture companies with the Kabila government. This was in an environment where “the constrains of governmental controls and regulations and a functioning legal system to enforce them” were “often absent.”64 Table 4 below shows a few of the joint venture companies that were formed between ZDI companies, Congolese and other companies.

62 S/2002/1146 (para 36). 63 Ibid. 64 Ibid., (para 79).

8 Table 4

Joint venture company Alleged Zimbabwean Alleged Congolese Alleged other partners partner partner SENGAMINES – the OSLEG COMIEX CONGO ORYX NATURAL largest joint venture (OPERATION 20% share of RESOURCES. company formed during SOVEREIGN the Sengamines 20% share of the DRC conflict LIGITIMACY). venture the Sengamines 40% share of the company. venture. Sengamines venture Provision of the Provision of company. resources to be financial and Controlled by exploited. technical Zimbabwe Defence capabilities Industries and needed for Zimbabwean resource military personnel. exploitation. Main contribution was to provide security for the Sengamines mining project No financial or technical capability to exploit minerals. ORYX ZIMCON ZIMCON ORYX 90% share of the 10% share of Oryx Zimcon. Oryx Zimcon Main contribution Provision of was the deployment financial and of troops to the technical Kasai area to protect expertise for the the project exploitation of infrastructure from the resources. invasion by disgruntled resident communities. COSLEG OSLEG COMIEX Largest timber exploration operation in the world.

20 In addition to these joint ventures, the Panel stated that there were others which were formed by elite networks linked to the “smuggling of precious metal, gems, arms trafficking,

9 illegal foreign exchange trading and money laundering.”65 The elite network consisted of “politically and economically powerful groups involved in exploitation activities which are highly criminalised”.66

THE FINAL REPORT OF THE PANEL 21 The Panel levelled allegations at some companies in its final report, in a process viewed publicly as naming and shaming them. It provided an exhaustive list of all the companies alleged to have played a role in fuelling conflict in the DRC. These companies were placed into Annex I, II and III of the final report. Annex I and II of the final report 22 These annexes contained a list of companies “that were involved in natural resource exploitation in a way which could be linked directly with funding the conflict and the resulting humanitarian and economic disaster in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.”67 The Panel possessed evidence that such companies had contributed, either directly or indirectly, to funding conflicts.68 Annex III of the final report 23 This annex listed companies that had indirect links to the DRC conflict. They were perceived by the Panel to bear the responsibility of ensuring that such links did not fund the conflict or contribute to its continuation in any way. Such companies allegedly benefited from the acquisition of concessions or other contracts from the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo on terms that were more favourable than they might have received in countries where there was peace and stability.69 These companies were said to generally be in breach of the OECD Guidelines (the Guidelines), the articles of which the Panel did not make reference to. EVALUATION OF THE PANEL’S WORK 24 After the Panel accused the companies in its final report, the UNSC issued Resolution 1457 which allowed companies to exercise their right to reply to the allegations made by the Panel against them. It stated that the UNSC: “ Invites, in the interests of transparency, individuals, companies and States, which have been named in the Panel’s last report to send their reactions, with due regard to commercial confidentiality, to the Secretariat, no later than 31 March 2003, and requests the Secretary-General to arrange for the publication of these reactions, upon request by individuals, companies and States named in the report.”70 25 Before the reactions of companies are presented, it is useful to highlight some weaknesses in the Panel’s mandate and methods.

65 Op. cit. note 37 (para 9). 66 S/2002/1146 (para 6). 67 Ibid., (para 9). Italics added for emphasis. 68 Ibid., (para 12). 69 Ibid. 70 S/RES/1457 (2003) para 11.

10 None of members of the Panel came from the Great Lakes region under investigation. Although the Panel consisted of five members throughout its existence between 2001 and 2003, the chair of the Panel changed twice, some members were with the Panel in 2001 only, while different members joined it from 2002 to 2003.71 These changes and the lack of representation of the Great lakes region within the Panel’s membership could have had a negative impact on the Panel’s understanding of the issues involved.

The Panel’s use of the OECD Guidelines as the standard for evaluating corporate behaviour was also questionable. The DRC was not in the OECD region, it was in a state of war and the Guidelines were not drafted to apply to such a context. Many of the state and non-state actors in the country were not from the OECD and the Guidelines would have meant very little to them. Notwithstanding this, the Panel stated that various companies were in breach of the OECD Guidelines without mentioning the specific provisions of the Guidelines these companies had allegedly breached.

According to the Panel’s mandate, it was a non-judicial body. Yet, the Panel was established for the sole purpose of carrying out investigations into illegal activities that were taking place in the DRC, without any reference to any legal texts. The evidence it obtained was from unnamed sources that could not be challenged by companies. The Panel subjected such evidence to a ‘reasonable standard of proof.’ ‘Reasonableness’ was not defined by either the UNSC or the Panel. The word ‘reasonable’ is vague and slippery, and the meaning of the terms differs from place to place and from time to time. There is equally no clarity provided on which legal standard the Panel used to judge the ‘reasonableness’ of the proof it obtained. Was it a criminal or civil standard? If it was the former, the Panel would have had to identify witnesses and subject their testimony to proof beyond reasonable doubt. If it was a civil standard, facts would have to be proved on a balance of probabilities. As far as the proof itself was concerned, the Panel did not state whether and which laws of evidence would apply. Clarity on this issue would have made a considerable difference to the companies against which the Panel had made allegations. 26 Companies that responded to the Panel’s allegations took issue with the methods used by the Panel to discharge its mandate. The reactions companies gave to the Panel’s accusations were useful for two reasons. Firstly, they raised strong arguments against the Panel’s modus operandi .Secondly, some of the reactions provided evidence of the ways in which companies interpret their responsibilities in weak governance zones and how they view standards such as the OECD Guidelines. Company reactions to the Panel’s report

71 2001: S/2001/49 and S/2001/357 Mme. Safiatou Ba-N.Daw (Côte d’Ivoire) (Chairperson); Mr. François Ekoko (Cameroon); Mr. Mel Holt (United States of America); Mr. Henri Maire (Switzerland); Mr. Moustapha Tall (Senegal). S/2001/1072 Brigadier General (Ret.) Mujahid Alam (Chairperson)(Pakistan); Mel Holt (United States of America); Henri Maire (Switzerland); Moustapha Tall (Senegal). 2002: S/2002/565 and S/2002/1146 Ambassador Mahmoud Kassem (Egypt) (Chairperson); Jim Freedman (Canada);Mel Holt (United States of America); Bruno Schiemsky (Belgium); Moustapha Tall (Senegal). 2003: S/2003/1027 Ambassador Mahmoud Kassem (Egypt), (Chairperson); Andrew Danino (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland); Alf Garsjb (Sweden); Mel Holt (United States of America); Bruno Schiemsky (Belgium); Ismaila Seck (Senegal).

11 Natural justice and Fair procedure 27 The publication of the names of companies in the Panel’s reports gave the impression that the Panel was implementing a criminal process. This is despite the fact, as mentioned earlier, that the Panel was established as a non-judicial body without the jurisdiction to pronounce on the guilt or innocence of any of the parties it investigated. The use of witnesses by the Panel and its public levelling of allegations against companies both in its reports and on the internet, were factors that made the Panel seem as though it was a judge and jury that passed judgment against companies. Furthermore, companies were only allowed to respond to the Panel after judgment had been made against them. Not surprisingly, companies were accordingly often highly critical of the Panel’s work and methods. a. The human rights of companies (juristic persons) 28 One of the major critics of the Panel’s modus operandi was BVBA Nami Gems, a Belgian diamond trading company. It saw the publication of allegations without prior notice to companies, as an abuse of company human rights and cited articles 2, 6, 10, 11 and 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as applying to companies.72 These articles protect the privacy, dignity, honour and reputation of all persons and also enumerate the rights of all persons to equality before the law. The articles give special attention to the right of all persons to a fair trial, including the right to be tried by an independent and impartial tribunal, in public and on the basis of an existing law. The articles also protect the rights of all to be presumed innocent before being accused of guilt. Whether or not this argument has any legal basis is arguable. b. Audi alteram partem – ‘Hear the other side’ 29 The audi alteram partem rule states that non-one should be condemned without a hearing in which they are given the opportunity to respond to the accusations made against them. Ahmad Diamond Corporation,73 Abadiam,74 Somikivu75 and Saracen,76 were companies that took the publication of allegations against them by the Panel as being a denial of their “rights” to due process. Effectively, they expected the Panel to contact them before the publication of allegations so as to give them an opportunity to defend themselves before the reports ‘naming and shaming’ them were published. c. Lack of transparency 30 The Panel was not accessible to any of the parties named in its reports. Many companies expected the Panel to hold discussions with them. BVBA Nami Gems stated that its officials made 47 attempts to contact the Panel through faxes, emails and telephone calls but according to them, received no response from the Panel. De Beers also stated that it waited seven months before the Panel responded to its attempts to establish communication.77 d. Evidence 31 Many of the companies complained that they had not seen any of the evidence on which the Panel based its allegations. They also took issue with the fact that they had no information pertaining to the witnesses who had raised these allegations with the Panel. For

72 S/2003/1146/Add.1 105. 73 Ibid. 74 Ibid., 142. 75 Ibid 76 Ibid 195-196 77 Ibid 175

12 example, the Managing Director of Saracen reported that when he met with the Panel he was not shown any evidence against the company because the Panel informed him that as a matter of policy, it would not divulge its sources.78 32 Subsequent to the responses it received from corporations, the Panel revised its method of categorizing companies according to their role in fuelling the DRC conflict and placed companies in five new categories. Category I - Resolved Status 33 Companies that made attempts to clear their names were placed into this category. Such companies left no outstanding issues to be resolved with the Panel. However, the Panel warned that this Resolved Status did not invalidate its earlier findings regarding the activities of the listed companies and that this came about as a result of the companies refraining from the illegal exploitation of natural resources. 34 Resolved Status was also given to companies which had taken action to remedy their actions or given firm, time-bound commitments to do so. For example, banks like Belgolaise that had formerly opened accounts for companies that were involved in questionable activities in the DRC closed such accounts and pledged to make their account opening procedures more stringent in the future. 35 Companies that ceased conducting businesses with Congolese companies which had traded in conflict resources were also placed on the Resolved Status list. Some companies which had allegedly hired corrupt Congolese government officials in order to gain lucrative mining concessions undertook to sever those ties and were placed on the ‘resolved status’ list. 36 Those companies that had originally been operating in the DRC before the conflict and had paid money to insurgents were also placed in this list. They were found to have been absolved of any wrongdoing because such activities were seemingly legitimate.79 The absolution of these companies by the Panel was on the basis that they contributed to the development of the communities in which they operated. 37 The Panel provided no clarity on the criteria used to resolve the issues between the named companies and the Panel. It said of companies in this category, the ‘original issues that led to their being listed in the annexes having been worked out to the satisfaction of both the Panel and the companies and individuals concerned.’80 Yet, this ‘should not be seen as invalidating the Panel’s earlier findings with regard to the activities of these actors.’81 This creates confusion because it is not clear why the Panel said issues were resolved when it also implied that they were not. Category II – Provisional resolution 38 The companies in this category made commitments to desist from suspicious activities. The Panel stated that it was ‘only a matter of going forward with improved controls and procedures that is required’82 for companies in Category II to be entered on the list in

78 Ibid 195. 79 Ibid.,5 (Para 9). 80 Op. cit. note 11 (para 23). 81 Ibid. 82 Op. cit. note 75 (para 29).

13 Category I. In the meantime, they were referred to National Contact Points (NCP’s) 83 of the member states of the OECD. These NCP’s would carry out further investigations on these companies. (Further information on the NCP process will be provided later in the paper). Category III – Referred for updating or further investigation 39 Companies on this list were also referred to the NCP’s of the OECD for further monitoring and investigation.84 These companies either failed to recognise the presence of any issues to be discussed with the Panel or failed to resolve issues with the Panel. One of them ‘refused to accept that it has any responsibility to do what it can to avoid providing support, even inadvertently, to rebel groups in conflict areas where it may be operating or have business interests.’85 Companies that had self-imposed business practice principles voluntarily on themselves but failed to adhere to these were also added to this category. Category IV – Referred for further investigations 40 Some governments whose corporate citizens were implicated in the report such as inter alia the UK, Belgium and the USA decided to conduct their own investigations on certain companies named in the Panel reports. Companies subject to such investigation were placed within this category. This step was heavily dependent on the political will of governments. Category V – Parties that did not react to the Panel’s report. 41 Parties that took no action to exercise their right of reply to the Panel’s report were placed in Category V. Category III and the National Contact Points of the OECD 42 In Annex III of its final report, the Panel referred various companies to National Contact Point’s (NCP’s) for investigation.86 NCP’s are offices that are established by members of the OECD in order to encourage the observance and implementation of the Guidelines. NCP’s handle enquiries about corporate adherence to the Guidelines, discuss related matters and assist in solving issues that may arise where adherence or lack of adherence to the Guidelines is concerned.87 They do not initiate investigations and rely on information provided by complainants. When the NCP has completed its process, it issues a statement of its findings.88 Conclusion 43 The reports of the Panel succeeded in highlighting the fact that corporations investing in conflict zones are placed within very close proximity to human rights violations and

83 Ibid. 84 National Contact Points for the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

14 accusations of being complicit in these harms. The reports are also useful in informing an understanding of the reputational risks faced by corporations entering into joint ventures with either state or non-state actors in conflict regions. 44 The Panel discharged its mandate without applying the audi alteram partmen or ‘hear the other side’ rule. This stands out as a major shortcoming of the panels work because the corporations mentioned in the reports were deserving of a chance to respond to allegations before the reports were placed in the public domain. 45 However, despite these methodological and other shortcomings in the drafting and discharging of the Panels mandate, the Panel succeeded in highlighting the fact that there was need for the setting out of special standards of behaviour for corporations operating in zones of weak governance. The Panel’s work provides a useful background to the use of the OECD Risk Awareness Tool for Multinational Enterprises in Weak Governance Zones adopted by the OECD Council in 2006. Any corporation that hopes to invest in a conflict zone should use both the Panel’s reports and the OECD Risk Awareness tool as a reference point.

15 Bibliography UN Security Council Expert Panel Reports on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of the Democratic Republic of Congo S/2001/49 16 January 2001. S/2001/357 12 April 2001. S/2002/565 22 May 2002. S/2002/1146 16 October 2002. S/2003/1027 23 October 2003.

Addenda to the UN Security Council Expert Panel Reports on the Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources and Other Forms of Wealth of the Democratic Republic of Congo S/2001/1072 13 November 2001 S/2003/1146/Add.1 20 June 2003

UN Security Council Resolutions Resolution 1457 (2003)

Websites

Books Zerk J. Multinational Enterprises and Corporate Social Responsibility (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2006)

16