To: The members of the ABF/Illinois Legal History Seminar

From: Angela Fernandez, Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Toronto

Date: April 4, 2011

Re: Pierson v. Post, the Hunt for the Fox

Please find here two chapters from my book project on the famous fox case, Pierson v. Post. I have also included here a casebook version of the reported case for those who are not familiar with it (I’ve included a version with translations for the Latin). It is not long and if you don’t know it, it really must be read to be believed.

The first two chapters of this proposed book deal with the social history of this case. Chapter 1 is about what motivated the parties in the original dispute, the beach where the fox hunt took place, and the legal status of that land. Chapter 2 focuses on the Justice of the Peace jury trial on Long Island in 1802, how the trial worked, who the JP was, who the jurors were and information about their social and economic backgrounds, and where the trial took place, a private home that probably also operated as a tavern.

The two chapters you have here are less social and more legal in their focus. Part of the reason why this case became a famous case at least in Long Island local history was the purportedly high costs the litigants were willing to pay to vindicate their rights. The involvement of lawyers was seen as key to the foolishness of the parties. Chapter 3 explores how lawyers became involved in the case and concentrates in particular on the lawyer of the party who appealed to the New York Supreme Court, Nathan Sanford. It also explains how the case became a property case rather than a tort case despite the fact that the original allegation involved malice. Chapter 4 then explains how the strategy Sanford took to win the case was risky and asks why he would have forfeited stronger (and more straightforward) arguments in favor of the ones he chose. The other lawyer had admitted that the fox was a “noxious beast’ and so rather than engage in the elaborate Roman and civil law arguments about how one acquired possession in animals ferae naturae, Sanford could have pointed out that foxes were not animals ferae naturae, they were vermin and as such could not be the subject of property. This chapter argues that the lawyers seemed intent on turning the case into a great debate, one that was premised not just on the fiction that the fox was an animal ferae naturae but also that the land on which the fox was caught was “wild and uninhabited, unpossessed and waste land,” a phrase that was partly true and partly not true, but which allowed the case to turn into a state of nature debate.

I look forward to speaking to you all further about the project and getting your reactions to the argument in these chapters.

A.F. [email protected]

1 Chapter 3: Lawyerization of the Case

Chapter 1 asked “How did this case begin?” As we saw, different conceptions of foxes in turn related to competing sources of standing and authority in this community were probably responsible for this case in the first place. Post took Pierson before a

Justice of the Peace because he saw what he had done as wrong, an impertinent interference with his hunt. Pierson took exception. As a member of a family with a lot of farmland in the area, he saw foxes as vermin and if you had a chance to kill one you did it quick. After all, in the hunt the fox might get away. Pierson might not have even seen himself as doing anything to Post, intentionally or maliciously (although he certainly did intend to take the fox knowing Post was hunting it and for all we know Post might have been right that it was with malice). As we saw in Chapter 2, although the jury technically found for Post, they really sided with Pierson and his conception of the fox – it was only worth 75¢ either as a pelt or as exterminated vermin.

What about the legal fees? Local history sources saw the involvement of lawyers as key to the foolhardiness in the case. When Adams included Hedges’s account of the fox case in his local history, he prefaced it by noting that the “love of lawsuits” had become “much more in the nature of luxuries” given that “by this time lawyers were employed.”1 When did lawyers become involved in this case? What role did they play?

What role did lawyers play?

1 Adams, 165. 2 According to the Justice of the Peace, John Fordham, Lodowick Post and Jesse Pierson appeared before him “in their proper person” on December 30th.2 To appear by proper person meant not to appear by way of attorney. When I first wrote about this, I thought that lawyers were not allowed to appear during this period in a magistrate’s court.3 The

1808 version of the Twenty-Five Dollar Act did expressly prohibit the appearance of lawyers.4 However, the 1801 version of the Act, the one that was used here, did not.5

Even if there had been an express prohibition on lawyers appearing, that does not mean that lawyers were not consulted. They might well have been consulted and then refrained from appearing with the parties in court. Is there any evidence that lawyers were involved from those early days?

We know that written pleadings were not required in a magistrate’s court.6 If they were not prohibited, however, that does not mean that were not used. And, indeed, there are suggestions that there were some in this case. Livingston wrote in his dissent that

“[b]y the pleadings it is admitted, that the fox is a ‘wild and noxious beast.’”7 Calling the fox a “wild and noxious beast” is a quote from somewhere, specifically, from the pleadings, this line in the reported case suggests. Fordham also referred to the fox in this exact way in his description of the case for the New York Supreme Court’s review and one assumes that he too was basing this upon the pleadings.8 Pleadings would suggest the involvement of a lawyer, at least in Post’s case.

2 Judgment Roll, p.4 3 See Angela Fernandez, “The Lost Record of Pierson v. Post, the Famous Fox Case,” 27 Law and History Review (2009): 149-79, 165, featured in “Forum, Pierson v. Post: Capturing New Facts about the Fox,” 27 Law and History Review (2009): 145-94. 4 See. s. 9, Twenty-Five Dollar Act (1808). 5 See Dan Ernst, “Pierson v. Post The New Learning,” 13 Green Bag 2d (2009): 31-42, 34, n. 6 (pointing out the correction). 6 Cowen, A Treatise on the Civil Jurisdiction of a Justice of the Peace, 320. 7 Case, 180. 8 See Judgment Roll, p. 4. 3 Charles Donahue thinks that the judgment roll “quite dramatically” confirms that

Post’s complaint was professionally made. Why? “Because even in 1802 only a lawyer could have produced the following piece of English prose: ‘did upon a certain wild and uninhabited[,] possessed and waste land, called the beach, find and start one of those noxious beasts called a fox.’”9 The reporter George Caines stated that he took the words from the declaration.10 This would seem to confirm that there were pleadings and these words came from Post, as the declaration is the first part of the plaintiff’s pleadings.11

Donahue wrote that Post’s complaint “has all the hallmarks of a document carefully drafted by a lawyer who was firmly on Post’s side.”12 Post’s lawyer on appeal was David

Cadwallader Colden.13 Colden was not from the area, so it seems unlikely Post went to visit him but it could have been another lawyer at this stage.14

Now what is odd about this phrase, as Livingston seems to see, is that Post’s lawyer called the fox a “wild and noxious beast” or a “noxious beast.” Why would he, as

Livingston put it, “admit” that the fox was in essence vermin? How then to avoid the conclusion that foxes should be killed whenever encountered by the most efficient means available? As Livingston put it, the fox is like a pirate whose “depredations on farmers and on barn yards, have not been forgotten; and to put him to death wherever found, is allowed to be meritorious, and of public benefit.”15 Andrea McDowell has written about this aspect of Livingston’s dissent, pointing out how wrong it is. Foxhunting, at least in

9 See Charles Donahue Jr., “Papyrology and 3 Caines 175,” 27 Law and History Review (2009): 179-88, 181. 10 Case, 175. 11 Black’s Law Dictionary, 6th ed. (St. Paul Minn: West Publishing, 1990), s.v. “declaration.” 12 Donahue, “Papyrology,” 181. 13 See Judgment Roll, p. 14. 14 Donahue, “Papyrology,” 182 (noting that “it seems unlikely that Colden was representing Post from the beginning. Colden was a fancy New York City lawyer”). Sanford was also a fancy New York City lawyer but, as we will see below, he had strong connections to Long Island and Suffolk County. 15 Case, 180. 4 England, was never understood to be a way of getting rid of as many “noxious beasts” as possible. On the contrary, foxes were considered very valuable (every hunt needed one), litters were carefully cultivated so as to have adults for the hunt, and it was a heinous act of villainy to poison, trap or shoot foxes intended for this purpose.16

Livingston did not of course draw the pro-Pierson inference from the view of the fox as a “noxious beast,” admitted or not. After describing the fox as a pirate, and indeed going on to call him other memorable things like the “wily quadruped,” Livingston argued that Post’s hunt ought not to have been spoiled. So, Livingston rhetorically asks, who could interfere with the person who keeps a pack of hounds, gets up at the crack of dawn, rides their horse all day, “if, just as night came on, and his strategies and strength were nearly exhausted, a saucy intruder, who had not shared in the honours or labours of the chase, were permitted to come in at the death, and bear away in triumph the object of pursuit?”17

Brockholst Livingston was one of the New York Livingstons, a wealthy and extremely politically well-connected family in New York State. Many people read

Livingston’s aristocracy as lying behind his decision to protect the hunter and the gentlemen’s code of conduct connected to Post’s claim.18 As Hedges wrote, Livingston’s

gentlemanly training and blood could not endure the thought that a gentleman,

enlisted in such an appropriate and laudable pursuit, in view of the fox, in pursuit

with his hounds, exalting in the anticipation of probable capture, should be

thwarted by the casual presence of perhaps a plebian spectator, who should

16 See McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 738, 750-52. Although there were areas of Britain like the Highlands where riding to hounds was not done and there foxes were simply pests or vermin. See McDowell, 757 (“[i]n areas that were too rocky and hilly for horses, too poor, or where there was not a critical mass of hunting families, foxes were in fact ‘just vermin’”). 17 Case, 181. 18 See e.g. Berger, “It’s Not About the Fox,” 1138-39. 5 without outlay or effort worth naming, slaughter and ruthlessly seize on the game

he had marked for his own. If that was law, what gentleman would be secure in

this gentlemanly pursuit?19

I see Livingston’s dissent as Lockean, as he explicitly referred to the “labours” that have gone into the hunt in terms of time and energy and his point is that the interloper’s interference with that should not go rewarded. After all, what resources had Pierson committed to the endeavor, coming along out of nowhere and clubbing the fox, as

Hedges put it, “without outlay or effort worth naming”? Livingston was the only judge or lawyer in the case to name Locke.20

McDowell wants us to notice that Livingston mixed into his dissent a generous dose of a false view of fox hunting, false at least from an aristocratic English perspective.

This would not seem to be the kind of mistake someone with his background would make. However, the puzzle here disappears when we realize that the phrase “wild and noxious beast” came from Post, who either knew his audience, in terms of the jury who would likely see the fox this way, or who made a tactical mistake. Livingston’s partial adoption of the view should be understood as an acknowledgment that the concession was made, while going on to argue that nonetheless, in his view, the activity should be protected from interference.

19 Hedges. 20 See case, 180. It is also possible to see Pierson’s side of the dispute as Lockean, as his family were the ones engaged in productive use of the nearby lands for farming, whereas Post’s recreation was not a Lockean optimal use of resources. However, the majority decision for Pierson carries none of this Lockean reasoning and Livingston’s dissent wears Locke on its sleeve. See also Charles Donahue Jr., “Animalia Ferae Naturae: Rome, Bologna, Leyden, Oxford and Queen’s County, N.Y.” in Roger S. Bagnall & William V. Harris eds., Studies in Roman Law in Memory of A. Arthur Schiller (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1986), 39-63, 58-59 (explaining how Livingston’s choice of Barbeyrac as the doctrinal writer supporting Post’s claim is a Lockean choice). 6 What about “wild and uninhabited, unpossessed and waste land”? The phrase appears no less than three times in the paragraph of Fordham’s account paraphrasing

Post’s complaint.21 However, as we saw in Chapter 2, while it is true that the beach was not individually possessed, it would be wrong to call it “unpossessed.” It might not have been individually possessed; however, the town acted as if it owned the entire beach, both above the high water mark and the foreshore between low and high tide. And while the beach was “waste” in the sense of being common land, it was not waste in the Lockean sense that was implied here, i.e. as “land that is left wholly to nature” and that is not useful because it is unimproved.22

Interestingly, when Livingston referred to the land in his dissent, he did not use

Post’s phrase “wild and uninhabited, unpossessed and waste land.” Livingston described the land on which the fox was started and hunted as “waste and uninhabited ground,” leaving out both the “wild” and “unpossessed.”23 It seems to me that this description of the land was more technically accurate than Post’s, since as we have seen, the land was not “unpossessed” and the sense of waste land that was meant was not the Lockean

“wild” and uncultivated kind. The phrase Livingston did use, “waste and uninhabited,” did actually fit the beach. As we saw in Chapter 2, the sense of “waste” meant here was common land. And it would seem to be relatively unproblematic to call the beach

“uninhabited,” since even if many people used it, no one actually lived on it.

If Livingston saw the problem with calling the land “waste” in the Lockean sense and “unpossessed” when it was not, why not take issue with it directly? As with the description of the fox as “wild and noxious,” Livingston was not free to do so, since this

21 See Judgment Roll, pp. 4-5. 22 Locke, Two Treatises of Government, 136. 23 See Case, 180. 7 was the description of the land in the declaration or pleadings. It was part of the statement of facts on appeal, which Pierson admitted were true in the claim he chose to pursue and the New York Supreme Court agreed to hear argument on.

Pierson had six grounds of complaint in the appeal, four of them purely procedural.24 However, the ground on which the case was decided at the New York

Supreme Court was on the so-called “third exception,” that Post’s claim was “not sufficient in law to maintain an action.”25 As Livingston put it, “[o]f the six exceptions, taken to the proceedings below, all are abandoned except the third.”26 The demurrer-like structure of this argument – conceding that all the facts alleged in Post’s claim were true but maintaining that even if they were, they were not enough to support an action against

Pierson – effectively precluded taking any issue with Post’s statement of the facts, including the description of the land. Livingston was as hemmed in by this as the parties were by the time of the appeal, specifically by the way that the lawyers framed the case.

An important question will be why they did it that way. However, first, we need more information on Pierson’s lawyer, Nathan Sanford. Who was he and how did he become involved in this case?

Pierson’s lawyer, Nathan Sanford

24 See Judgement Roll, 10-13. For a detailed review, see Fernandez, “Lost Record,” 172-74. But see note ? below. 25 Case, 175 (the reporter Caines stating that “the defendant there [Pierson] sued out a certiorari, and now assigned for error, that the declaration and the matters therein contained were not sufficient in law to maintain an action”). See also Judgment Roll, p. 12 (Sanford, Pierson’s lawyer, claimed in the third exception that “the matters contained therein [i.e. Post’s “declaration[,] complaint[,] or demand”] are not sufficient in law for the said Lodowick Post to have[,] maintain[,] or support his said action against the said Jesse Peirson and therefore the said judgment thereupon rendered and given is vicious[,] erroneous[,] and void in law”). 26 Case, 180. 8 Nathan Sanford was a prominent lawyer who practiced in New York City and

Albany. However, he was from the area of Long Island where the fox fight took place.

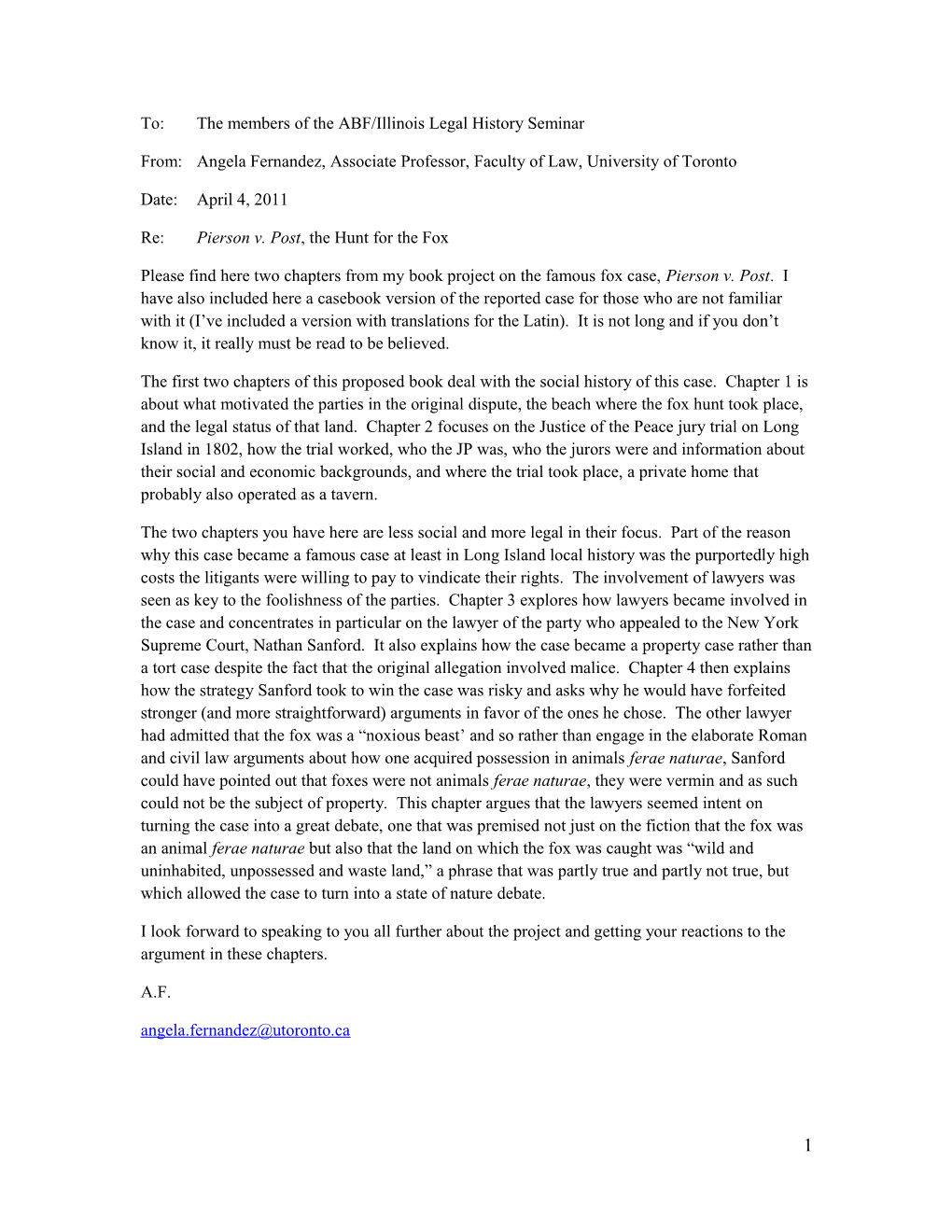

He owned a family house in Bridgehampton, where he was born (see Map at Figure 11 at the corner of Woolsey Lane and Scuttle Hole Road marked “Hon Nathan Sandford”).27

Scuttle Hole is in a village known as Mecox, southwest of Sag Harbor and north of

Sagaponack.

[Figure 11 – Reproduced from an Appendix in William Donaldson Halsey, Sketches from Local History (Southampton, New York: Yankee Peddler Book Company, 1966)]

27 This house no longer stands, having burned down sixty or so years ago. See Ernest S. Clowes, Wayfarings: A Collection Chosen from Pieces Which Appeared Under That Title in the Bridgehampton News, 1941-1953 (Bridgehampton, N.Y., 1941), 120 (writing that the “Old Sanford House” burned to the ground about two weeks ago). 9 It is unclear what connection Sanford kept with the Scuttle Hole house once he grew up and moved from the area. We know he was left land when his father died in 1787 when

Nathan was just ten years old.28 His father was a Justice of the Peace and a man of standing and importance in the community, whose wealth probably came from whaling and cattle.29 Thomas was elderly when he married Nathan’s mother, Phebe (Baker)

Howell, and she was his second wife. She died in 1796.30 Nathan was said to have been

“carefully reared by his mother’s relatives,” attended the prestigious Clinton Academy in

East Hampton before entering Yale College in 1793 where he studied for two years and was then called to the bar in 1799.31

Clinton Academy was named after Dewitt Clinton and it had three streams, the

Classical Department, the English Academical Department, and the Common School.32

We do not know which of the three streams Sanford was in. However, one local historian wrote that “[h]e must have had an unusual mind and some unusual teachers [at Clinton

Academy] who recognized it, for he quickly developed a taste for the best in literature and for problems of the mind.”33 He came to be known as “a finished scholar, as familiar

28 See Grover Merle Sanford, The Sandford/Sanford Families of Long Island: Their Ancestors and Descendants (Baltimore: Gateway Press, 1975), 19. 29 Phone conversation with Ann Sandford, August 25, 2009. 30 Merle, 19. 31 Ibid., 27. Berger wrote citing to a conversation with Ann Sandford that Nathan Sanford “was the child of uneducated parents, but with the encouragement of the Piersons was able to attend the prestigious Hayground Academy.” “It’s not about the Fox,” 1134. Hayground Academy seems to be a mistake for Clinton Academy. I have not been able to substantiate the point about being encouraged by the Piersons. Sanford was related to the Piersons on his father’s side, not his mother’s side. See note ? below. 32 Tuition depended on which stream a student belonged to, 30 shillings per quarter for the Classical (“a regular classical education” plus other subjects such as geography, navigation, and mathematics), 20 shillings a quarter for the English Academical (“a Miscellaneous Education” of reading, writing, arithmetic, English grammar, rhetoric, composition, “sentimental and epistolary,” and French), and for the Common School it was 9 shillings, six pence per quarter for those who only read and 12 shillings per quarter for anyone else. See Rules and Regulations for the Government of Clinton Academy in East-Hampton (Sagg Harbor: David Frothingham, 1794), copy provided by Rosanne Barons, Registrar, East Hampton Historical Society. 33 Clowes, Wayfarings, 120. 10 with the French language as with his own, and in later life he made himself master of both Spanish and Italian. The Latin poets were his delight, and he solaced his leisure with their richness and beauty.”34

Upon being called to the bar, Sanford was admitted as an attorney in the New

York Supreme Court and the Court of Common Pleas of New York City, otherwise known as the Mayor’s Court.35 He was made a counselor of the latter court in early 1801 and a solicitor of the Court of Chancery in 1802.36 As a supporter of the Tammany faction of the Jeffersonian Republican Party, he was to receive some important public appointments from Thomas Jefferson, including a position as a Commissioner of

Bankruptcy.37 The best of these came in 1803, an appointment as United States District

Attorney for Southern New York, a position he held for twelve years that was reputed to bring him $10,000 annually in fees.38 In other words, in late 1802, he was a busy and up- and-coming, though not yet as wealthy and super-eminent as he would later come to be, as a United States district attorney and then later still as a member of the state legislature, state senate, United States senate, and the eventual replacement of James Kent as the

34 Ibid., 121. 35 Sanford’s diplomas are in a set of his papers at the New York State Library in Albany. See “Certificate of admittance as Attorney at Law, January 25, 1799” & “Certificate of admittance as Attorney at Law, February 26, 1799,” Nathan Sanford Papers SC14054, Folder 1. The first was his admittance to the New York Supreme Court and the second was to “the Court of Common Pleas called the Mayor’s Court.” 36 “Certificate of admittance as a Counsellor at Law, February 4, 1801” & Certificate of admittance as a Solicitor of the Court of Chancery, March 15, 1802,” Nathan Sanford Papers SC14054, Folder 1, New York State Library, Albany, N.Y. 37 “Appointment as a Commissioner of Bankruptcy, District of New York,” no date, signed by James Madison, Jefferson’s Secretary of State. It would therefore have been sometime between 1801 and 1809. Nathan Sanford Papers SC14054, Folder 1, New York State Library, Albany, N.Y. 38 Edward Conrad Smith, “Nathan Sanford,” Dictionary of American Biography. In an unflattering portrait of Sanford, James Kent wrote that Sanford made a fortune in this office “by his multiplied & Vexatious Prosecutions during the Embargo times. His Charges were enormous & he had the Control of the Confidence of M.B. Tallmadge the district Judge. I remember that John Wells expressed the utmost abhorrence of the oppressive administration of Justice under Sanford & Tallmadge.” Donald M. Roper, “The Elite of the New York Bar as Seen from the Bench: James Kent’s Necrologies,” 56 New York Historical Society Quarterly (1972): 199-237, 230. 11 Chancellor of New York State. By 1805, the time of the appeal in this case, he was already a very important lawyer-politician and wealthy.39

Descendant and student of Sanford’s life, Ann Sandford, thinks Nathan’s older step-brother Thomas who never married probably lived in the Scuttle Hole house.40

However, Thomas, the eldest child of his father’s first marriage, was left a legacy; the land went to Nathan.41 This inheritance would presumably have included this house.

Step-brother Thomas died ca. 1789.42 However, Southampton town tax assessment rolls list Sanford’s real property, defined as “house and land,” at $2000 in 1801 and $2800 in

1803.43 Nathan probably maintained residences in both New York City and Albany appropriate to his busy practice in both cities. However, Ann Sandford believes that his family and financial interests would have kept him in close contact with people on the

South Fork of Long Island and traveling there.44

How early did Sanford become involved in the case? He might have been consulted if he was at home in Bridgehampton sometime after the incident on December

10, 1802 and before the Justice of the Peace Proceedings on December 30, 1802. There is a record book of Sanford’s cases before the New York City Court of Common Pleas or

39 Kent’s objections to Sanford were manifold. He “suddenly abandoned the federal [party] & joined the democratic Party, & became an admirer of Jefferson & corresponded with him.” “He was always in my view a hard, avaricious heartless Demagogue … He removed to Albany after having buried two wives & was hated for his Character and Conduct … He spent his last years in building a most extravagantly expensive but inconvenient House.” “He was a member of the Convention in 1821” – the convention that forced the retirement of many of the old Federalists like Kent – “& succeeded me as Chancellor,” a point that must have rankled particularly. 40 Email to the author from Ann Sandford (September 1, 2009). 41 Sanford, The Sandford/Sanford Families of Long Island, 19. 42 Ibid. 43 There is no entry for personal property, as presumably, living elsewhere, he was taxed on this elsewhere. Sanford is also listed in 1806 as being taxed (in conjunction with someone named Silas White) on “house and land” worth $2800. The tax assessment roll for 1818 lists his value of Sanford’s house and land at $6200. Tax Assessment Rolls, 1801, 1803, 1806, 1818. 44 Email to the author from Ann Sandford (September 1, 2009). 12 Mayor’s Court.45 Based on the four cases in this record book in which clients were retained in December 1802 and steps in their cases were taken in December 1802 and

January 1803, there are two gaps, periods when Sanford might well have come home to

Bridgehampton, especially as this was at Christmas time.46

The first period is from December 10th to December 22nd 1802.47 The initial incident over the fox happened on December 10, 1802 and it seems that Pierson was notified orally some time on or after December 22nd that he would have to appear at the hearing on December 30th.48 Assuming Pierson would have waited until after notification to bring the case to Sanford, it is difficult to see how this could have taken place in person. If Sanford was back in New York City working on December 23rd, the two-day stage coach ride from Bridgehampton to Manhattan would have had him leaving the area

45 “Registry of Court Cases 1799-1812,” Sanford Family Paper SC23075, New York State Library, Albany, N.Y. [hereinafter Mayor’s Court Registry]. 46 See ibid., 72 (Gelston v. Cornwall); 73 (Smith v. Davidson); 74 (Smith v. Harris); 75 (Smith v. Pheonix). 47 In Gelston v. Cornwall, “9 December 1802 Gave notice of being retained to Bogert [attorney for the plaintiff – Sanford was retained by the defendant the day before on December 8].” Mayor’s Court Registry, 72. Sanford was retained by the plaintiffs in Smith v. Davidson, Smith v. Harris, and Smith v. Pheonix on December 23, 1802. Mayor’s Court Registry, 73, 74, 75. 48 December 22 was the date that Fordham issued the order for either of the Southampton constables to summon Pierson to appear on December 30. See Judgment Roll, pp. 8-9. When I first wrote about this, I thought that the six-day notice period between summons and appearance had been violated as Sanford claimed. See Fernandez, “Lost Record,” 172-73; Judgment Roll, p. 11-12. However, the record contains an endorsement by the constable in the case that he served Pierson by reading the summons to him. See Donahue, “Papyrology,” 183. I transcribed some difficult-to-read handwriting as “Jesey Parson” rather than Jesse Peirson. See Judgment Roll, p. 9. Sanford’s claim that the service happened on December 30 seems to be based on a lack of precision in Fordham`s description. See Judgment Roll, pp. 3-4. Pierson was likely served orally by the Constable within the six-day period and not served on December 30 even though the wording Fordham used caused Sanford to write that “it appears in and by the said record” that the summons happened on December 30. See Judgment Roll, 11 [emphasis added]. It seems likely that Sanford was grasping at straws here. Another of Sanford’s certiorari cases from 1805 sheds some light on the other procedural objections. In Brown v. Smith, Law Judgment S-82, Sanford tried the point about the wording of the direction to the Constable in the summons, namely, that it should not be to “any” Constable but should be directed to a particular one. See Fernandez, “Lost Record,” for an explanation of why that is a picky point. Sanford also tried to claim, as he did in Pierson v. Post, that it was a manifest error that the Justice of the Peace rather than the jury found the costs. I wrote in the “Lost Record” that I had not been able to ascertain whether or not that was a valid objection. However, Brown v. Smith was a case where the Justice of the Peace assessed costs and the New York Supreme Court blessed this. See Brown v. Smith, 3 Caines 81 (1805). As Caines’s marginal note puts it, “costs follow by the statute, and therefore need not be found [by the jury].” 13 on December 21st. The second period in which Sanford seems to have been absent from his New York City practice is from December 29th to January 10th.49 Again, given the two-day ride, he might have arrived on the 30th (his last working day seemed to be

December 28). There would not have been much time for advance consultation given that the proceedings began at 2:00 pm on that day.

It is of course possible that Pierson simply contacted Sanford by mail sometime after the incident (December 10) or after Pierson was notified of the court date, i.e. sometime on or after December 22. The eight days until December 30 would certainly have allowed time for correspondence back and forth about this. The two families, the

Piersons and the Sanfords, were connected – Nathan Sanford’s paternal grandmother was a Pierson.50 It is not inconceivable that Pierson would have reached out to him in that way even if Sanford did not make any visits to the area at that time. An absence from working in New York City might just as easily have meant time in Albany or even other activities in New York City or a vacation there. If he was in Southampton during that second period, December 29th to January 10th, Pierson would certainly have seen him about the appeal. In any event, Pierson must have got in touch with Sanford sometime before the end of January, since Sanford was granted the writ of certiorari on January 29,

1803.51

It is worth noting that if Sanford did visit the area in December/January of that year or was talking to his friends and family there, he would almost certainly have heard

49 On December 28 in Smith v. Harris and Smith v. Pheonix he “filed bill obtained copy of rule to plead and served it with copy of bill on defendant” in both cases. Mayor’s Court Registry, 74, 75. The earliest date back in January of the New Year is January 11. See Smith v. Davidson, Mayor’s Court Registry, 73. 50 The father of Nathan’s father, Thomas Sandford, married Sarah Pierson in 1709. She was the daughter of Colonel Henry Pierson. Also, Thomas’s older brother, Zachariah, married Mary Pierson, sister of Sarah. Email to the author from Ann Sandford (September 1, 2009). 51 See Judgment Roll, pp. 1-2. 14 about the scuffle. We now know from the judgment roll that the Justice of the Peace proceedings involved seven witnesses.52 We do not know who these people were or what role they played. At least some of them might have been the “companions” Hedges mentioned in his account who were hunting with Post.53 However, such a high number of witnesses show that many people got involved in the case and many more would have had knowledge of it.

[Figure 12 – Reproduced from Mary Cummings, Images of America:

Southampton (Charleston, S.C.; Chicago, IL; Portsmouth, NH; San Francisco, CA:

Arcadia Publishing, 1996), 26]

52 Judgment Roll, p. 10. 53 Hedges. 15 The picture in Figure 12 is obviously from a later date. However, it gives a sense of the way in which the capture of a fox could be a notorious event in Southampton. If the show down between Pierson and Post on December 10 had anything like this amount of interest, one can easily see how it might have come to Sanford’s attention. It also makes it a little easier to see how the fox might well become a vehicle through which to express other issues related to community standing and the collective meaning of local practices.

No one who has read E.P. Thompson’s classic Whigs and Hunters can doubt the tremendous social significance that can readily attach to hunted deer, hunting dogs, stolen horses, and poached rabbits when members of a community were staking out competing claims and managing (sometimes intense) conflict.54

The Lawyers’s Strategy

There are at least two indications that Post originally brought his claim in tort rather than property. The first is that he used the writ of trespass on the case rather than trespass.55 The second is that we now know that Post emphasized malice in the original complaint.56 The case is even stronger now to say, as Andrea McDowell did, that “there are signs that Post originally sued in tort.”57

54 See E.P. Thompson, Whigs and Hunters: The Origin of the Black Act (New York: Pantheon Books, 1975). 55 Case, 175. 56 See Judgment Roll, p. 5. 57 McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 738. McDowell made the point about malicious interference before we knew that the complaint explicitly alleged malice. See e.g., 738 (“the harm Post suffered was malicious interference with the hunt”); 739 (“Post’s counsel could have framed his claim as malicious interference”); 739 (“Post’s immediate grievance was not the loss of the fox, but that Pierson maliciously interfered with his hunt”). 16 Trespass on the case is the writ that eventually grew into the tort of negligence.58

It evolved in Chancery as the way to construct new writs for different injuries that bore “a certain analogy to trespass” that were evaluated on a case by case basis or “on the particular circumstances of the case.”59 This is sometimes described as “a writ suited to the plaintiff’s ‘case.’”60 “[T]he injuries themselves which are the subjects of such writs

… have the general name of torts, wrongs or grievances.”61 Trespass on the case or

“case” is the form of action “adapted to the recovery of damages for some injury resulting to a party from the wrongful act of another, unaccompanied by direct or immediate force, or which is the indirect or secondary consequence of the defendant’s act.”62 So, for instance, while Pierson’s primary motive might well have been to kill the fox (seeing the fox through a farmer’s eyes as a threat to livestock, particularly chickens), the indirect or secondary consequences of his actions were to wrong Post, whose hunt was spoiled.

If Pierson did “maliciously kill” the fox and did “maliciously take and carry [it] away,” as Post charged in his complaint,63 that would change our sense of how direct the wrong was. Consider the following example from Roman law, provided by Donahue writing about the case. Does an action lie against a person prohibiting me from using the public baths?

58 Black’s Law Dictionary, s.v. “Trespass on the case” (the action is “the ancestor of the present day action for negligence where problems of legal and factual cause arise”). 59 John Bouvier, A Law dictionary adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America, and of the several states of the American Union; with references to civil and other systems of foreign law vol. 2 (Philadelphia, Penn.: T & J.W. Johnson, 1839) (NY, NY: Lawbook Exchange, 1993), 503-504, s.v. “writ of trespass on the case.” 60 Elizabeth Jean Dix, “The Origins of the Action of Trespass on the Case,” 46 Yale Law Journal (1936- 37): 1142-76, 1143 (citing and quoting from Blackstone’s definition, borrowed from William Lambard, “a writ of case gives the suitor ‘ready relief, according to the exigency of his business, and adapted to the specialty, reason and equity of his very case’”). 61 Bouvier, 504 (emphasis in the original). 62 Black’s, s.v. “trespass on the case.” 63 Judgment Roll, p. 5. 17 Clearly the action will lie in my favor if a strong man bars the doors of the baths

against me, but what if he simply takes the last place in the baths and uses it

himself? Normally, he would be free to do this; the baths are, after all, public.

But he is not free to do this … if his purpose is not to take a bath himself but to

prevent me from taking one.64

Malice and perhaps even just knowledge that there was an intention to take and the thwarting of that intention is an iniuria. This is not about property (an in rem right against the world); it is about a wrong (an in personam right held by the victim, personal to the person who committed the wrong). Or, as Donahue put it, “the point of Post’s suit against Pierson is not that Pierson took Post’s fox. The point is that Pierson interfered with the hunt.”65

However, one can see why Post’s lawyer did not want to go forward with this claim even though he (or his predecessor) brought the case as a tort. There were at least two serious problems with proceeding in this way. The first was that there is no such tort as malicious interference with the hunt. As Brian Simpson has pointed out, the common law has traditionally refused to protect “things of mere pleasure and delight.”66

Acknowledging Post’s claim in the terms in which he brought it, would have been like asking the court to create a new tort.67 As McDowell noted, “[e]ven today, it would be difficult to state a cause of action at common law for malicious interference with the hunt.”68

64 Donahue, “Animalia Ferae Naturae,” 49-50. 65 Donahue, Ibid., 48; see also Charles Donahue 1985, 611. 66 A.W.B. Simpson, “The Timeless Principles of the Common Law: Keeble v. Hickeringill (1707)” in A.W.B Simpson ed. Leading Cases in the Common Law (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), 45-75, 64. 67 McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 773. 68 Ibid., 774. 18 Post’s second problem was that unlike trespass where the plaintiff does not need to prove harm, trespass on the case, like negligence, does require an injury in order to obtain damages, the remedy the writ requests.69 Although trespass on the case invited a court to find that a legal wrong had been committed “on the particular circumstances of the case”70 or “as suited to the plaintiff’s case,”71 the fact that Post suffered no injury would have created a problem for his claim. As McDowell put it, Post “hunted for pleasure and suffered no economic loss.”72 Post needed a property claim in the fox.

Without a property claim in the fox, namely, something he was made to lose by virtue of the wrong Pierson committed against him, Post could not show he suffered any harm. In other words, without the property argument, Post would not have been able to make out the elements of his torts case.73

So, for instance, Blackstone defined “personal actions” as those in which a debt, personal duty, or damages were claimed and those “whereby a man claims a satisfaction in damages from some injury done to his person or property. The former are to be founded on contracts, the latter upon torts or wrongs.”74 In other words, a tort requires injury to person or property. There would not seem to have been any injury to Post’s person. However, there was arguably an injury to Post’s property. Animals ferae naturae were a species of “qualified” property. As Blackstone clearly stated, “in animals ferae naturae a man can have no absolute property.”75 Generally, damage to things

69 See John G. Fleming, The Law of Torts, 8th ed. (Sydney, Australia: The Law Book Company, 1992), 17 (“Trespass was actionable per se, that is, without proof of actual damage, whereas generally damage was of the gist of case”). 70 Bouvier, 504. 71 Dix, “The Origins of the Action of Trespass on the Case,” 1143. 72 McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 772. 73 McDowell called this “shoehorning” the case “into a property mold,” 735. See also 738, 774 (“Post’s claim depended on his having some property interest in the fox”). 74 Blackstone, Commentaries, 3:117. 75 Blackstone, Commentaries, 2:390. 19 personal “while in the possession of the owner, as hunting a man’s deer, poisoning his cattle, or in any wise taking from the value of his chattels … these are injuries too obvious to need explanation,” Blackstone wrote.76 Such actions were either with force

(trespass vi et armis) or not (a special action on the case, where the injury is inconsequential and arises without any breach of the peace).77 “In both of these suits the plaintiff shall recover damages in proportion to the injury which he proves that his property has suffered.”78 In other words, Post needed property in the fox.

These problems with Post’s case explain why Colden wanted to reframe the case as a property-law case at the New York Supreme Court, agreeing in particular to omit the point about malicious interference that was in the original complaint. It was, as

McDowell put it, “a defective torts case.”79 Trespass to Post’s “‘property’ in the fox was the only legally cognizable harm he [Post] had.”80 Post needed to make out the property claim in order to get anywhere, including holding onto his $5.75 award at the appeal level of the case, where Pierson was “the now plaintiff.”81

It is helpful to contrast Pierson v. Post with an unreported fox case from

Connecticut McDowell located, Sharpe v. Sabin (1796).82 Here trespass, rather than trespass-on-the-case was pleaded, and the plaintiff explicitly invoked the costs of keeping dogs and hounds and claimed, using property language, that the interloper hunter

“convert[ed]” the fox pelt, worth twelve shillings to his own use.83 There was no jury in this case. The parties appeared themselves before an Assistant and the plaintiff was

76 Blackstone, Commentaries, 3:152. 77 Ibid., 152-53. 78 Ibid., 153 (emphasis added). 79 McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 735. 80 Ibid., 772. 81 Case, 175. 82 Reproduced in McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 777. 83 Ibid. (emphasis added). 20 awarded 7 shillings, or about 35 pence or 70¢, almost the same as the 75¢ the jury gave

Post.84 Unlike Pierson v. Post, this was a true hunting case; the defendant was (unlike

Pierson) another hunter. Hence, the plaintiff claimed that intentionally interfering with the hunt after he started the fox and was in close pursuit of it “was & is against Law & the Customs & rules of Hunting.”85 The defendant claimed, as Pierson also did, that “the matters therein contained are wholly insufficient in Law to support any action against the defendant.”86 However, the appeal court did not reverse as the New York Supreme Court did in Pierson v. Post.

Now the jury in Pierson v. Post was unlikely to have cared much about what writ the case was brought in, trespass or trespass on the case. Nor would it have mattered much to them whether on a tortuous claim Post suffered the requisite injury, or whether he was able to show that he acquired a property right in the fox superior to Pierson’s in order to show that injury. Those questions of what writ was used in the case and property versus tort would likely have been seen by them as irrelevant. Their concern was affirming the New England view of foxes as worth no more than $1, either as a pelt or as exterminated vermin.87 They would be inclined to take a common sense approach and give Post the small remedy they thought he deserved, without worrying too much about what category of law to attach it to, property or tort, or who more legitimately could claim possession of the fox.

In effect, the jury’s verdict mixed the tort claim with the property claim. It recognized the wrong done to Post, a malicious interference with his hunt, without

84 Presumably because it was not a jury trial, the costs were less than $5, namely, ₤1, 5 shillings and 20 pence. Ibid. 85 Ibid. 86 Ibid. 87 Sharpe v. Sabin, ibid., seems to confirm that this was the New England view of foxes, as it was from Connecticut and it also gave an under $1 award. 21 requiring Post to show a property claim in the fox, i.e. that something of his that was harmed or injured. Yet, at the same time, the jury used the fox’s property value, either as a pelt or as exterminated vermin, to give an award, albeit a small one, to Post. This was not a matter of insignificant financial import given Fordham’s tallying of $5 in costs for

Pierson to pay. Pierson’s lawyer was quite right to notice that a fundamental confusion had occurred. The jury should not have used the property measure unless Post had property in the fox. As Sanford put it, “[i]f … Post had not acquired any property in the fox, when it was killed by Pierson, he had no right in it which could be the subject of injury.”88 So far so good. However, Sanford then went on to concede that “a property may be gained in such an animal.”89

There was no need for Sanford to concede that foxes were a species of ferae naturae. Foxes had been traditionally seen under the common law as vermin.90 For instance, Bacon’s Abridgment repeatedly used the phrase “fox, badger, or any Animal of the Vermin Kind” in its entry on “trespass.”91 “[F]oxes were an anomaly within the genre of ferae naturae,” McDowell explained. “Far from being potential property, foxes and other vermin were legally classified as nuisance, the killing of which was a service to the public.”92 Yes, foxes could be the valuable objects of recreational pursuit. Yet, in this case, Post admitted that the fox was a “noxious beast.”93 The jury also found that the fox was only worth 75¢, about the same as the bounty given for the animal as exterminated

88 Case, 175. 89 Ibid. 90 McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 746. 91 See e.g. vol. 5, A New Abridgement of the Law. By Matthew Bacon, of the Middle Temple, Esq.: The fourth edition, corrected, with many additional notes and References of and to Modern Determinations … (London, 1778), 180 (emphasis added). 92 McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 748. 93 See ? above, explaining that according to Caines these words came from the declaration, the first part of the pleadings, and Livingston stated that “[b]y the pleadings it is admitted, that the fox is a ‘wild and noxious beast.’” Case, 180. 22 vermin.94 Sanford should have pointed out that if foxes were vermin at common law, and this fox was vermin as Post himself admitted and as the jury arguably viewed it, it was not possible for Post to have any property in it. There therefore could not have been any injury to Post’s property. That was the strongest reason for saying, as he wanted to, that

“there was no title in Post, and the action therefore [is] not maintainable.”95 Pierson should not have had to pay anything, not just the 75¢ but also the $5 in costs.

Post’s lawyer had no choice but to argue Post’s hunt gave him property in the fox.

Without property in the fox, Post was unable to show the injury that a tort required.

However, one would have expected Sanford to point out the two weakest points in this argument. First, there was no such thing as a tort of malicious interference with the hunt.

And second, even if there was, a tort would require injury to property and Post had not acquired property in the fox because the fox was vermin (by Post’s own admission) and it was not possible to have property in vermin. Why did Pierson refrain from using what to all appearances was a devastating argument against Post? Why did Sanford opt instead for what we will see was a much more risky argument about how one established possession in animals ferae naturae?96

94 See above. 95 Case, 176. 96 Case, 180. 23 Chapter 4: A Great Debate & Legal Fictions

Animals ferae naturae

At the New York Supreme Court, Sanford did not argue that Post could not have property in the fox because fox were vermin. Nor did he argue that property was required in order for Post to show the damage required in order to succeed in a tort claim.

Nor did he argue that there was no such tort. Nor did he argue any of the procedural grounds about which he had originally complained. Instead, Sanford and Colden agreed to limit argument to the third exception, understood particularly as whether Post’s pursuit of the fox gave him enough of a claim to it to sustain his action against Pierson. As

Tompkins put it, “[t]he question submitted by the counsel in this cause for our determination” is whether Post by his pursuit of the fox acquired a right to or property in the fox sufficient to sustain an action against Pierson.97 In order to establish Pierson’s superior possession, Sanford went to Justinian, a strategy that was by no means guaranteed to be successful in the case.

Sanford quoted in Latin from a passage from the Institutes relating to wild animals.98 The first point he made was the general one from Justinian that wild beasts when seized become the property of their captor by the law of nations “for natural reason admits the title of the first occupant to that which previously had no owner.”99 Sanford then made the more specific point that this stays as the captor’s property “so long as it is completely under your control; but so soon as it has escaped from your control, and recovered its natural liberty, it ceases to be yours, and belongs to the first person who

97 Case, 177 (emphasis added). 98 See Case, 176. 99 English translation taken from The Institutes of Justinian, Institutiones, John Baron Moyle, trans. (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1913), 37. 24 subsequently catches it.”100 Even if wounded, “it may happen in many ways that you will not capture it.”101 This was on its face a strong authority for Pierson, since the idea was that even if Post originally had the fox in his sights, it escaped and came to belong to

Pierson, the first person who caught it.

However, Charles Donahue has pointed out that this passage from Justinian is not as definitive vis-à-vis Pierson as Sanford pretended.102 The passage states that an animal will be considered to have regained its “natural liberty” moving out of the pursuit-based claim of the original hunter where he has “lost sight” of the animal, “or when, though it is still in [his] sight, it would be difficult to pursue it.”103 However, in this chase, the fox had not escaped so that it was out of sight nor was pursuit difficult. At least according to

Livingston, Post was “on the point of seizing his prey.”104 Or, as Livingston also put it,

Post was “within reach.”105 Now neither the judgment roll nor the reported case were as clear about this as Livingston would have liked, or as clear as Sharpe v. Sabin, the unreported Connecticut fox case, was, by contrast. In that case there is no doubt that the plaintiff was about to take the fox – “in all reasonable Probability the sd Hounds would either have caught & killed sd fox or would have drove sd fox within reach of the Pltf’s

Gun in such manner that the Pltf might have shot him.”106 Sanford himself even referred to the point about how an animal re-acquires its natural liberty.107 However, the Justinian passage was not really the right source for Pierson to use if this was a case where Post

100 Ibid. 101 Ibid. 102 Donahue, “Animalia Ferae Naturae,” 48. 103 Institutes, 37. The same point is made in a parallel passage in the Digest. See Justinian, Digest 41, 1 &2 , F. De Zulueta (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1963), 6 (Latin), 46 (English). 104 Case, 180. 105 Case, 182. 106 McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 777. 107 Case, 176. 25 was about to take the fox. Indeed, the parallel discussion to the Institutes in Justinian’s

Digest makes it seem like the point about reducing the animal to actual capture was specific to situations in which the original hunter had wounded the animal.108 There was certainly no intimation that Post had wounded the fox. The Justinian passage was therefore arguably inapposite in another way.

Colden was standing at the ready with his counter-authority, Barbeyrac on

Pufendorf.109 Pufendorf himself had left the point at issue between Pierson and Post undecided. In The Law of Nature and Nations, Pufendorf defined “the most early

Occupant,” as “he who lays hold on such a thing before others, or gets the start of them in putting in his Claim to it.”110 This was ambiguous who, as between, Pierson (who laid hold of the fox) or Post (who initiated the hunt), would be the first occupant and therefore the rightful owner. In Barbeyrac’s annotated version of this text, he says that “that taking

Possession actually (Occupatio) is not always absolutely necessary to acquire a thing that belongs to no body.”111 A person can also make their intention to take known so long as the thing is “within Reach of taking what he declares his Design to feixe on.”112 Colden relied on this in order to make his point that “manucaption” was only one way “to declare the intention of exclusively appropriating” what was in a state of nature. Pursuit should give “a person who starts a wild animal … an exclusive right whilst it is followed.” So

108 See Justinian, Digest, 46. 109 Case, 176. 110 Samuel Pufendorf, Law of Nature and Nations: Or, a General System of the Most Important Principles of Morality, Jurisprudence, and Politics. In Eight Books. Written in Latin by the Baron Pufendorf, … Done into English by Basil Kennett, … To which is prefix’d, M. Barbeyrac’s prefactory discourse, … Done into English by Mr. Carew, … To which are now added, all the large notes of M. Barbeyrac, translated from his fourth and last edition: together with large tables (London: Printed for J. and J. Bonwicke, R. Ware, J. and P. Knapton, S. Birt, T. Longman and others, 1749), 386. 111 Ibid. 112 Ibid. 26 long as that pursuit continues, it is the equivalent of occupancy, as “it declares the intention of acquiring dominion.”113

Now Sanford dismissed Colden’s argument by calling Barbeyrac’s status into question – “[t]he only authority relied on is that of an annotator.”114 However, that seemed to be an unfair argument, as Barbeyrac was an author who was held in high esteem. John Adams’s mentor, Jeremiah Gridley, preferred Barbeyrac’s notes to

Pufendorf’s text.115 Barbeyrac was the French translator of Pufendorf’s Latin text, and the 1749 translation by Basil Kennet from French to English of all of the text, including

Barbeyrac’s notes, was the edition Americans used.116 Thomas Jefferson had both books in his library and cited extensively from the latter in notes he made in a divorce case.117

“The most frequently used edition of Pufendorf was that by Barbeyrac, whose own commentary on the text was itself cited with approval in a number of cases.”118 Charles

Donahue has explained that on the pursuit question Puffendorf was Hobbesian, the law is based on what you can take and secure; whereas Barbeyrac believed in a natural right to take what you had declared your design to and were about to take.119

There were other authorities siding with Barbeyrac. The Roman law scholar

Trebatius, for instance, thought that as long as the animal was being pursued it belonged

113 Case, 176-77. 114 Case, 177. 115 Daniel R. Coquillette, “Justinian in Braintree: John Adams, Civilian Learning, and Legal Elitism, 1758- 1775” in Law in Colonial Massachusetts, 1630-1800: A conference held 6 and 7 November 1981 by the Colonial Society of Massachusetts (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1984), 359-418, 382 n.7. 116 See e.g. David Hoffman, A Course of Legal Study: Respectfully addressed to the students of law in the United States (Baltimore, 1817), 71 (describing two English translations of Pufendorf’s work and noting that the one by Kennett with Barbeyrac’s notes “is the most valuable”). 117 See Frank L. Dewey, Thomas Jefferson Lawyer (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1986), 66- 67. Cited by Hoeflich, Roman Law in America, 5-6. 118 Christopher P. Rogers, “Continental Literature and the Development of the Common Law by the King’s Bench: c. 1750-1800” in Vito Piergiovanni, ed., The Courts and the Development of Commercial Law (Berlin: Duncker and Humblot, 1987), 161-94, 169. 119 Donahue, “Animalia Ferae Naturae,” 56-58. 27 to the pursuer but if the pursuit ceased then it became the property of the first taker.120

When James Kent later annotated his copy of Pierson v. Post, he made a note to the

French doctrinal writer, Robert-Joseph Pothier, next to the part of Tompkins decision that said: “[i]t therefore only remains to inquire whether there are any contrary principles, or authorities, to be found in other books, which ought to induce a different decision.”121

Pothier wrote about the problem of possession of wild animals in his property treatise, where he said specifically of the hunt “it is sufficient that the animal be in the person’s power in a manner in which it cannot escape.”122 As the Justinian passage made plain, the problem with Post’s pursuit was precisely that the fox might get away. However,

Pothier noted Barabeyrac’s position that pursuit should be sufficient, calling this the more civilized sentiment that was followed in practice and grounded in an old law of the

Salians.123 Pothier’s book was in French and not translated into English.124

How did Sanford know that someone – Colden, Tompkins or Livingston – might not point out that Justinian did not authoritatively settle the case? What if one of the judges was like Jeremiah Gridley and thought that Barbeyrac on Pufendorf was the true genius and not a mere annotator? What if someone could and did read Pothier in French and argued that he, unlike Barbeyrac, however eminent, was a true authority, since he was held in almost reverential esteem as a legal scientist?125 There are a number of

120 See Ingham, Law of Animals – A Treatise on Property in Animals Wild (1900), 5-6 (interesting for its disagreement with Pierson v. Post) and Justinian’s Digest, 46 (also mentioning the Trebatius position in the wounding context). 121 Fernandez, “A Great Debate,” 314 (reproduces the text with handwritten annotation). See Fernandez, “A Great Debate,” 317-18 (explaining how Kent’s annotation does not match up to the property treatise). 122 Robert-Joseph Pothier, Traité du droit de domaine de propriété, de la possession, de la prescription qui resulte de la possession, vol. 10, Oeuvres Complètes de Pothier, M. Siffrein ed. (Paris: Chez Chanson, Imprimeur-Libraire, 1821), 16. 123 Ibid., 18. 124 Indeed, it still is not. Hence the translation in the above text is my own. 125 The property treatise was finished in 1772 and was used along with Pothier’s other treatises in the drafting of the French Civil Code in 1802. See J.E. De Montmorency, “Robert-Joseph Pothier and French Law,” 13 Journal of the Society of Comparative Legislation (1913): 265-87, ?. 28 possibilities here and it really does seem like Sanford took an unnecessary risk in the case by conceding that foxes were animals ferae naturae, as it really was “a knotty point,” as

Livingston put it. It was certainly a lot less straightforward than simply pointing out that at common law foxes were vermin, especially as Post conceded that fact in the pleadings themselves by calling the fox a “noxious beast.”126

As Tompkins put it, “[i]t is admitted, that a fox is an animal ferae naturae.”127

That meant that despite the concession that foxes were vermin, the case turned into a more general debate about animals ferae naturae and the lawyers and judges focused on whether Post’s pursuit established property in the animal sufficient to sustain an action against Pierson for taking it. Why did Sanford handicap his case in this way?

An arranged case?

Now it is certainly possible that Sanford simply did not know that at common law foxes were vermin. A text like Bacon’s Abridgment, which contained an entry on trespass with the vermin point, was recommended at least as a standard piece of reading.128 McDowell wrote that Livingston “was clearly aware of the older law treating foxes as vermin.”129 One would think that Sanford, an established and prominent lawyer, noted in particular for his deep learning, would also be familiar with this point. If he was, it looks like he intentionally thwarted the safest argument in the case so that he and

Colden could have a debate about how one acquires possession in animals ferae naturae.

Imagine an exchange between the lawyers like the following:130

126 Case, 175. 127 Case, 177. 128 See e.g. Hoffman, A Course of Legal Study, 149-51. 129 McDowell, “Legal Fictions in Pierson v. Post,” 758. 130 Inspired by Donahue’s similar dialogue in “Papyrology,” 182-83. 29 Sanford: Look Colden, I’ve got you. No way out. You can’t make out your action. There’s no such tort as malicious interference in the hunt. There is no property in vermin. No property means no injury and no injury means no trespass on the case.

Colden: Yes, damn it, you’ve got me.

Sanford: Here then, why don’t we change the argument from foxes to animals ferae naturae and whether Post’s pursuit was sufficient to obtain a property right. You remember those texts – Justinian, Grotius, Barbeyrac on Pufendorf?

Colden: Well yes, vaguely. I suppose that would give me some chance at success.

Sanford: Come on, it will be fun.

Now we need to be careful about using a retrospective diagnosis that makes it seem as if it was obvious the lawyer should have done X or Y in the case. Hindsight is

20/20, as they say. Legal Archeology projects take a long time and these cases, by contrast, happened in real time.131 A lot of very smart legal academics have studied

Pierson v. Post, and it has been a slow and difficult process coming to understand the tort and property issues. Much of this would have been more familiar to legal actors in the early Nineteenth Century than it is to us, living as they did before the Judicature Acts of the late Nineteenth Century, when much still turned on the “fine-spun and cabalistic learning about trespass and case.”132 Still, I do not think one can say it was obvious that

Sanford should have argued as I have sketched here, even if it is puzzling why he did not

131 See Judith L. Maute, “Peevyhouse v. Garland Coal & Mining Co. Revisited: The Ballad of Willie and Lucille,” 89 Northwestern Law Review (1995): 1341, ? (discussing the time issue). Sanford’s substantive grounds of complaint – that the facts were not sufficient to maintain the action and that the verdict was against the law of the land – seemed to be standard inclusions on certiorari appeals to the New York Supreme Court from Justice of the Peace proceedings. In other words, he probably did not decide on his strategy when the appeal was filed in January 1802. That presumably means he would have had the full two and a half years until the case was heard and decided to decide on strategy, although we do not know when he and Colden decided to limit argument to “the third exception.” 132 See Fleming, The Law of Torts, 18. 30 make some of these arguments at least in the alternative, especially given Post’s concession that the fox was a “noxious beast.”133

Even assuming Sanford would have had the trespass-on-the case and vermin arguments at his fingertips, the above imagined scenario has a problematic assumption, namely, that it places most of the impetus for framing the case at Sanford’s feet. He risked losing the case, the dialogue implies, so that he could pull out his Latin and the

Justinian he was known to love, and so he and Colden could have a great debate on how one acquires possession in animals ferae naturae. However, it was Colden or his predecessor, not Sanford, who planted the first seed for the case to go in the broad philosophical direction it did, specifically, by characterizing the land in the case as “wild and uninhabited, unpossessed and waste land.”134

As we have seen, this phrase was not a very accurate description of the beach. It was not unpossessed (since it was possessed by the town) and it was only waste land in the sense of being common land (not in the Lockean sense of waste land). It was certainly not unowned. However, that state of nature description of the land allowed for an unfettered treatment of the problem of pursuit of animals fera naturae, since private ownership or ownership by the state or the town would have complicated both Pierson and Post’s claim to have property in the fox. Ownership of the land on which animals ferae naturae were caught was a contentious issue and legal authorities disagreed on how absolute the right to take animals ferae naturae should be.

One view was that animals fera naturae were free for the taking wherever they were. Absent statutory laws restricting hunting, anyone could take these animals even

133 Case, 175. 134 Case, 175. 31 when they were on the property of another. English game laws famously fettered this ability to access animals like deer and were seen by many as illegitimate.135

Other authorities placed more weight on the principle of ratione soli, a principle of ownership “[o]n account of the soil; with reference to the soil.”136 So, for instance, in his History of English Law, John Reeves stated that animals ferae naturae were not the property of anyone. However, they had an incomplete property that accrued ratione soli and gave the owner title to an action for injury done to them.137 Blackstone stated that “if a man starts game on another’s private land and kills it there, the property belongs to him in whose ground it was killed, because it was also started there, the property arising ratione soli.”138 However, if the animal was chased onto someone else’s land and killed there, then the property vested in the hunter who started and chased it, although he would be guilty of a trespass against the first landowner.139 Joseph Chitty wrote in his treatise on the game laws later in the Nineteenth Century that a person could acquire property in the animals on the land of another but nonetheless be guilty of a trespass.140

The Pierson v. Post lawyers and judges were probably aware of some of these complications relating to animals ferae naturae and a free taking approach v. limits imposed by ratione soli.141 Sanford cited to a passage in Blackstone very close to passage 135 See e.g. Thompson, Whigs and Hunters, 140 (describing how “persons of estate and quality” were involved in opposition to the exclusive attitude taken in the policing of deer parks and royal forests, “the old-established resident gentry … who perhaps shared some of the same attitudes toward forest rights and to deer of their humbler tenants”), 162 (two hunters convicted under the Black Act “could scarcely be persuaded that the crime for which they suffered merited death. They said the deer were wild beasts, and that the poor, as well as the rich, might lawfully use them”). 136 Black’s Law Dictionary, s.v. “Ratione soli.” 137 John Reeves, History of the English Law: from the time of the Saxons, to the end of the Reign of Philip and Mary (London: Reed and Hunter, 1814-1829), 370. 138 Blackstone’s Commentaries, 2:419. 139 See ibid. There was no such complication in the case as the fox was started, chased, and killed, all on the beach. 140 See Joseph Chitty, A Treatise on the Game Laws and on Fisheries: with an appendix containing all the statutes and cases on the subject, vol. 1 (London, W. Clarke, 1812), 6. 141 Though not it seems on the point about starting the animal on one person’s land and killing it on another’s, as the facts in the report (probably prepared by the reporter Caines) did not specify where the fox 32 relating to ratione soli in a section of the Commentaries called “Of Title to Things

Personal by Occupancy.”142 According to Blackstone, animals ferae naturae could be taken by all mankind and this was a natural right unless restrained by the laws of the country.143 Tompkins actually referred to the principle of ratione soli twice in his decision. First, in the following passage, explaining why English case law was unhelpful in deciding Pierson v. Post:

Most of the cases which have occurred in England, relating to property in wild

animals, have either been discussed and decided upon the principles of their own

statute regulations, or have arisen between the huntsman, and the owner of the

land upon which beasts ferae naturae have been apprehended; the former

claiming them by title of occupancy, and the latter ratione soli.144

The second time was in reference to the duck hunting case, Keeble v. Hickeringill, where the defendant shot guns to scare away ducks on the plaintiff’s land. The plaintiff’s duck keeping was economic and not recreational (he invested in the construction of an elaborate duck trap). The ducks were on the plaintiff’s own land (although they had not yet been reduced to possession) and the defendant shot the guns from his land and so there was no trespass.145 Tompkins pointed out that in Keeble v. Hickeringill the was killed. See Case, 175. 142 Case, 176 (citing to Blackstone’s Commentaries, 2:403). 143 See Blackstone’s Commentaries, 2:403 (“with regard likewise to animals ferae naturae, all mankind had by the original grant of the creator a right to pursue and take any fowl or insect of the air, any fish or inhabitant of the waters, and any beast or reptile of the field: and this natural right still continues in every individual, unless where it is restrained by the civil laws of the country. And when a man had once so seized them, they become while living his qualified property, or, if dead, are absolutely his own: so that to steal them, or to otherwise invade this property, is, according to the respective values, sometimes a criminal offence, sometimes only a civil injury. The restrictions which are laid upon this right, by the laws of England, relate principally to royal fish, as whale and sturgeon, and such terrestrial, aerial, or aquatic animals as go under the denomination of game; the taking of which is made the exclusive right of the prince, and such of his subjects to whom he has granted the royal privilege”). 144 Case, 178. 145 On the problems related to figuring out what precisely Keeble v. Hickeringill stands for given no less than four versions of the reported case, see Simpson, “The Timeless Principles of the Common Law,” 64- 65. Two of the reports emphasized malice. See at 65. 33 plaintiff’s “possession of the ducks, ratione soli” made it “clearly distinguishable from the present.”146

Pointing out that the beach was owned by the state or by the town would not have made the state of nature debate in Pierson v. Post impossible by any means. Even if there was some kind of special regulation or custom as to who could take things from the beach (oysters, clams, seaweed, beach grass, fish, whales), it is unlikely that there were rules about foxes, as they were not an economic resource. Neither Pierson nor Post was committing a trespass by being on the beach, as they were not on land that was privately owned. This was public land in some sense. However, the careful lawyerly description of the land as “wild and uninhabited, unpossessed and waste land,” accurate in some respects but not in others, seems like it was drafted in order to make any complications relating to who owned the land disappear, clearing the way for a debate that could take place as if the beach was unowned land in a state of nature. The lawyers could offer a pure philosophical treatment as if it were a state of nature debate.

Lon Fuller wrote about how the common law develops by way of “as if” reasoning, arguments by analogy that take the form of legal fictions that we know are not literally true but help conceptualize new phenomenon or create an acceptable shorthand by way of reasoning in comparison to something familiar (e.g. corporate personality, deemed consent, constructive notice).147 In this case, the half-accurate, half-inaccurate characterization of the land as “wild and uninhabited, unpossessed and waste land” gave the lawyers and the court the freedom to treat the case as raising “a novel and nice question”148 – neat and clean with no complications. This fiction, and it certainly was a

146 Case, 179. 147 See Lon L. Fuller, Legal Fictions (Stanford University Press, 1967). 148 Case, 177. 34 fiction, put the parties on an equal footing, since whoever did own the land (the state or the town), it was not either of the parties and the principle of ratione soli had no purchase and could not therefore compete with acquisition by occupation.

Tompkins wrote in his opinion that there were two “admissions [that] narrow[ed] the discussion to the simple question of what acts amount to occupancy, applied to acquiring right to wild animals.”149 The first was Sanford’s concession that “a fox is an animal ferae naturae.”150 The second was the admission that “property in such animals is acquired by occupancy only,” and not by some competing complicating factor like ownership of the land.151 The point about malice disappeared and the “defective tort case” became a pure property case.

Now Colden (or his predecessor) and Sanford would have had to have been in communication from the case’s earliest days to have set the case up in this way and that seems unlikely. Imaginary dialogues like the one above are entertaining and help us imagine possibilities, but we cannot take them for what actually happened. However, we do know that by the time of the appeal, the lawyers agreed to take the case in the direction they did. Sanford conceded that foxes were animals ferae naturae, and Colden tried his best to win on those terms. However it came to be, the case was argued as if foxes were animals ferae naturae and as if the land was unowned, creating the conditions for a debate about how one acquires possession of animals ferae naturae in the state of nature.

Assuming that there was arrangement in the case to some extent, namely, agreement on the fictional preconditions for the case that resulted in Sanford putting

149 Case, 177. 150 Ibid. 151 Ibid. 35 forward a much less strong argument than he could have, does that make Pierson v. Post a collusive case? Black’s defines a collusive action as “[a]n action not founded upon an actual controversy between the parties to it, but brought for the purpose of securing a determination of a point of law for the gratification of curiosity or to settle rights of third persons not parties.”152

Perhaps the most famous example of a collusive case is Fletcher v. Peck (1810), where the buyer and seller of a large tract of the Yazoo lands brought a case to secure the court’s ruling that a corrupt legislative process that originally created the land grants did not invalidate the deeds of subsequent purchasers.153 The judge in dissent at the United

States Supreme Court, Johnson J. wrote that the case “appears to me to bear strong evidence, upon the fact of it, of being a mere feigned case. It is our duty to decide on the right, but not on the speculations of parties.”154 Here, “speculations” was indeed what was meant given the kinds of interests that were at stake in this and other large land purchase situations where title was unclear.155 Although in Fletcher v. Peck, Johnston J. did not insist that this was a collusive case, writing that his confidence “in the respectable gentlemen who have been engaged for the parties, has induced me to abandon my

152 Black’s Law Dictionary, s.v. “collusive action.” 153 See Lindsay G. Robertson, Conquest by Law: How the Discovery of America Dispossessed Indigenous People of their Lands (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 31 (explaining how the New England Mississippi Land Company feigned breach of contract between one shareholder of the company, Robert Fletcher of New Hampshire, and another, John Peck of Massachusetts. Fletcher filed suit against Peck for making false warranties in the fabricated deed between them. The jury in the District Circuit Court for Massachusetts found for Peck and Fletcher requested a writ of error from the United States Supreme Court. “By this clever strategy,” the company circumvented the barrier imposed by Congress on Supreme Court appeals from the territorial courts, including the Mississippi Territorial Court). 154 Fletcher v. Peck, 6 Cranch 87, 147 (United States Supreme Court, 1810). 155 See Kathryn Preyer, “Federalist Policy and the Judiciary Act of 1801,” in Blackstone in America: Selected Essays of Kathryn Preyer Mary Sarah Bilder, Maeva Marcus, and R. Kent Newmyer eds. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 10-38, 29-35. 36 scruples, in the belief that they would never consent to impose a mere feigned case upon this court,” we know that it was.156

The United States constitution, Article III, section 2, imposes a “case or controversy” requirement on the federal judiciary.157 While state constitutions do not necessarily do the same, state supreme courts do require the existence of a genuine adversarial context for a dispute.158 When the point about collusion is litigated, it usually appears as a preliminary procedural issue. The charge tends to be dismissed as long as there is some kind of controversy between the parties. So, for instance, even in the face of evidence of actual collusion between the parties, courts have said that “despite the subjective desires of the parties, their legal interests and duties created an actual controversy.”159 One way of framing the test is to ask whether antagonistic interests existed when the case was filed.160

By these standards Pierson v. Post was not a collusive case. It was based on an actual, genuine or real controversy between the parties. In other words, antagonistic interests existed when the case was filed. Both lawyers were no doubt curious about what determination of law the court would give on the pursuit point. However, it does not appear that the case was brought in order to secure that determination, even if the seed for the debate was built in from the beginning by the characterization of the land as

“wild and uninhabited, unpossessed and waste land.” As we saw in Chapter 1, as