Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View MOA Exhibition Guide

Museum of Anthropology Exhibition Guide Includes list of MOA exhibitions by year and list of material in the MOA archives that is related to each exhibit. Exhibitions listed according to year The titles, dates, and descriptions of exhibitions are taken directly from the MOA Calendar of Events. However, the start dates and end dates on the MOA Calendar of Events, at times, do not correspond with the ‘actual’ dates of the exhibitions. Therefore, if you require more information on the ‘actual’ exhibition dates please cross reference the dates listed on this list with those listed on the MOA exhibitions’ web page. Table of Contents: Year of 1976 ......................................................................................................... 3 Year of 1977 ......................................................................................................... 4 Year of 1978 ......................................................................................................... 6 Year of 1979 ......................................................................................................... 7 Year of 1980 ......................................................................................................... 8 Year of 1981 ......................................................................................................... 9 Year of 1982 ....................................................................................................... 10 Year of 1983 ...................................................................................................... -

Untitled, Lamp 11.5” X 30” X 7.5”, Cedar, Paint, Found Materials

THE BLANKET EXERCISE – A POTLATCH 67–67 TEACHING March 02 + June 08 2018 Native Son’s Hall / 360 Cliffe Ave Courtenay FILM SCREENING: POTLATCH 67–67 July 05 2018 Sid Williams Theatre / 442 Cliffe Ave Courtenay HIŁTSISTA’AM‘ ‘ (THE COPPER WILL BE FIXED) WELCOMING / ART OPENING / CEREMONY / ART TALKS July 20 2018 Comox Valley Art Gallery / 580 Duncan Ave Courtenay COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT / CULTURAL SHARING July 21 2018 The Kumugwe Bighouse / 3240 Comox Road Courtenay CLOSING CEREMONY October 04 2018 Comox Valley Art Gallery / 580 Duncan Ave Courtenay JULY 20 – OCTOBER 04 2018 Comox Valley Art Gallery / 580 Duncan Ave Courtenay OUR ANCESTORS GUIDE US Beau Dick / Sam Henderson / Tony Hunt / Mungo Martin ARTISTS Jesse Brillon / Corey Bulpitt / Liz Carter / Rande Cook / Donna Cranmer / Andy Everson / Karver Everson / Shawn Hunt / George Littlechild / Marianne Nicolson / John Powell / Steve Smith / Connie Watts WELCOMING / ART OPENING / CEREMONY / ART TALKS July 20 / 6pm Comox Valley Art Gallery / 580 Duncan Ave Courtenay COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT / CULTURAL SHARING July 21 11am–4pm The Kumugwe Bighouse / 3240 Comox Road Courtenay CLOSING CEREMONY October 04 2018 Comox Valley Art Gallery / 580 Duncan Ave Courtenay The exhibition Hiłtsista’am’ ’ (The Copper Will Be Fixed) is part of the convergent program Potlatch 67–67: The Potlatch Ban – Then And Now, produced by the Kumugwe Cultural Society, led by Cultural Carrier Nagezdi, Rob Everson, Hereditary Chief of the Gigalgam Walas Kwaguł and Guest Curator Lee Everson, in collaboration with the Comox Valley Art Gallery. Visit comoxvalleyartgallery.com and potlatch6767.com for the full program. 3 The path to true reconciliation will be realized only when the quality of life of Indigenous peoples across the country are equal to other Canadians, when culture and language are preserved and practiced for future generations. -

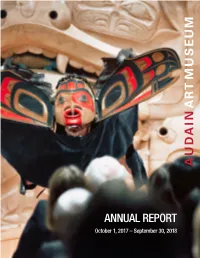

2017-2018 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT October 1, 2017 – September 30, 2018 CONTENTS 03 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR 04 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR & CHIEF CURATOR 06 SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS 11 COLLECTION 16 PUBLICATIONS 17 EDUCATION & PUBLIC PROGRAMS 22 SUPPORT 26 AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 39 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 40 MUSEUM STAFF 41 VOLUNTEERS COVER IMAGE James Hart (1952 – ) The Dance Screen (The Scream Too), 2010 – 2013 Red cedar panel with abalone, mica, acrylic, wire and yew wood 479.0 x 323.0 cm Image: Todd Easterbrook Gathie Falk (1928 – ) Arsenal, 2015 Bronze with white patina 80.0 x 71.1cm Audain Art Museum Collection Purchased with funds from the Audain Foundation 02 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR On behalf of the Board of Trustees, the Audain Art Museum (AAM) is pleased to present the October 2017 – September 2018 Annual Report for review. This past year has been filled with many highlights. The AAM presented a number of Special Exhibitions including Beau Dick: Revolutionary Spirit, a retrospective exhibition chronicling the life and art of this master carver and Kwakwaka’wakw hereditary chief. Stone & Sky: Canada’s Mountain Landscape, a Canada 150 project presenting over 100 works of art, spanning 150 years, as well as the very popular POP! exhibition from the Smithsonian American Art Museum augmented with a number of pop art pieces by British Columbian artists. September saw a much anticipated event. Master carver and hereditary Haida Chief James Hart together with his singers, dancers and drummers performed the inaugural ceremonial dance of The Dance Screen (The Scream Too). This event symbolized an iconic moment for the AAM and a once in a lifetime opportunity to witness a piece of Northwest Coast art and culture, merging traditional history with the contemporary. -

Constructing a Collection's Object Biography

The Kwakwaka’wakw Potlatch Collection and its Many Social Contexts: Constructing a Collection’s Object Biography by Emma Louise Knight A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Museum Studies Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Copyright by Emma Louise Knight 2013 The Kwakwaka’wakw Potlatch Collection and its Many Social Contexts: Constructing a Collection’s Object Biography Emma Louise Knight Master of Museum Studies Faculty of Information University of Toronto 2013 Abstract In 1921, the Canadian government confiscated over 400 pieces of Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch regalia and placed it in three large museums. In 1967 the Kwakwaka'wakw initiated a long process of repatriation resulting in the majority of the collection returning to two Kwakwaka’wakw cultural centres over the last four decades. Through the theoretical framework of object biography and using the museum register as a tool to reconstruct the lives of the potlatch regalia, this thesis explores the multiple paths, diversions and oscillations between objecthood and subjecthood that the collection has undergone. This thesis constructs an exhibition history for the regalia, examines processes of institutional forgetting, and adds multiple layers of meaning to the collection's biography by attending to the post-repatriation life of the objects. By revisiting this pivotal Canadian case, diversions are emphasized as important moments in the creation of subjecthood and objecthood for museum objects. ii Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank Sarah Holland, who introduced me to this collection in her UVIC museum studies class in 2010, continued to encourage me over the years, and who invited me into her home in Alert Bay for what would be a life-changing experience.