Torts Outline - ELLIS Procedural Notes

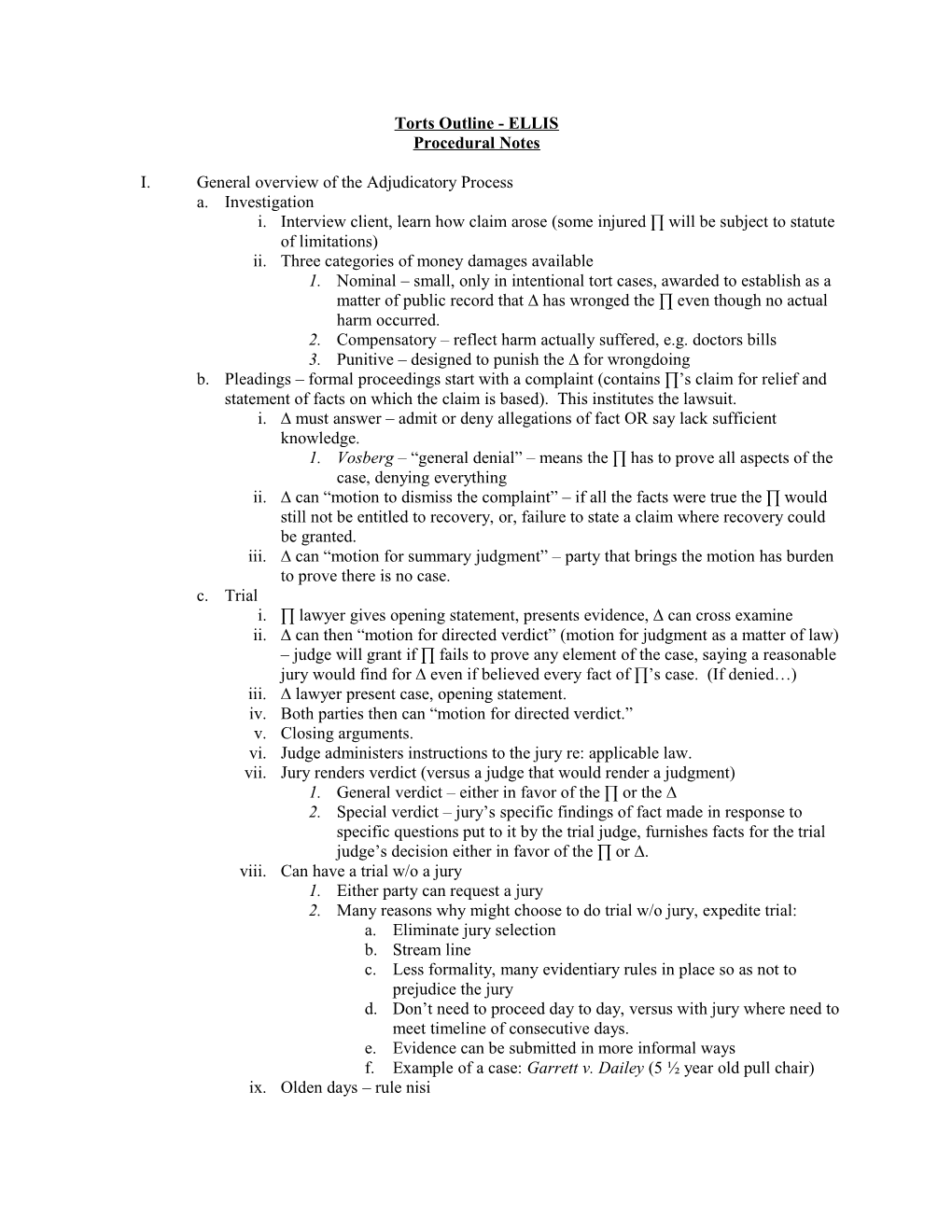

I. General overview of the Adjudicatory Process a. Investigation i. Interview client, learn how claim arose (some injured ∏ will be subject to statute of limitations) ii. Three categories of money damages available 1. Nominal – small, only in intentional tort cases, awarded to establish as a matter of public record that ∆ has wronged the ∏ even though no actual harm occurred. 2. Compensatory – reflect harm actually suffered, e.g. doctors bills 3. Punitive – designed to punish the ∆ for wrongdoing b. Pleadings – formal proceedings start with a complaint (contains ∏’s claim for relief and statement of facts on which the claim is based). This institutes the lawsuit. i. ∆ must answer – admit or deny allegations of fact OR say lack sufficient knowledge. 1. Vosberg – “general denial” – means the ∏ has to prove all aspects of the case, denying everything ii. ∆ can “motion to dismiss the complaint” – if all the facts were true the ∏ would still not be entitled to recovery, or, failure to state a claim where recovery could be granted. iii. ∆ can “motion for summary judgment” – party that brings the motion has burden to prove there is no case. c. Trial i. ∏ lawyer gives opening statement, presents evidence, ∆ can cross examine ii. ∆ can then “motion for directed verdict” (motion for judgment as a matter of law) – judge will grant if ∏ fails to prove any element of the case, saying a reasonable jury would find for ∆ even if believed every fact of ∏’s case. (If denied…) iii. ∆ lawyer present case, opening statement. iv. Both parties then can “motion for directed verdict.” v. Closing arguments. vi. Judge administers instructions to the jury re: applicable law. vii. Jury renders verdict (versus a judge that would render a judgment) 1. General verdict – either in favor of the ∏ or the ∆ 2. Special verdict – jury’s specific findings of fact made in response to specific questions put to it by the trial judge, furnishes facts for the trial judge’s decision either in favor of the ∏ or ∆. viii. Can have a trial w/o a jury 1. Either party can request a jury 2. Many reasons why might choose to do trial w/o jury, expedite trial: a. Eliminate jury selection b. Stream line c. Less formality, many evidentiary rules in place so as not to prejudice the jury d. Don’t need to proceed day to day, versus with jury where need to meet timeline of consecutive days. e. Evidence can be submitted in more informal ways f. Example of a case: Garrett v. Dailey (5 ½ year old pull chair) ix. Olden days – rule nisi 1. Wants the court to enter a verdict for the ∆ unless the ∏ can show that it was an assault, it’s a rule from a superior court to show cause. See: Read v. Coker (page 655) 2. [Latin: unless] (Of a court’s ex parte ruling or grant of relief) having validity unless the adversely affected party appears and shows cause why it should be withdrawn. 3. Moving party goes to court of common pleas and obtains from them a rule nisi. In this case it is comparable to an “order to show cause.” It’s an ex parte motion, one moves in order to show cause and the opponent does not get to be heard whether the order will issue. An order to the opposing party to show cause why something shouldn’t happen. In this case it is an order to show cause why judgment should not be granted for the ∆. The rule nisi is granted and then the court and then discharges the rule that the ∏ has met the causation requirement. Read v. Coker. 4. Rule nisi – A “rule” is an order from one of the superior courts, and a “rule nisi” is such an order “to show cause.” That is, the rule is to be held absolute unless the party to whom it applies can “show cause” why it should not be so. x. Losing party can move for “JNOV” (judgment notwithstanding the verdict) – judge would allow this if against weight of evidence, excessive damages awarded, procedural errors during trial, or if verdict could manifest injustice. Either party can “motion for a new trial” if verdict appears to judge to be against clear weight of evidence. [Need to look at evidence in the light most favorable to the non-moving party]. d. Exceptions to regular trial procedure i. Garret v. Dailey and Hackbart (football) – Trial Court hears all the evidence and reaches a decision based on that evidence. Trial judge makes finding of fact AND determines the law. Appeals court remands for a reconsideration of the evidence (findings of fact by the trial court). 1. In the case of Hackbart it was because new issue (not public policy, but rather if ∏ had a personal tort claim). 2. In Garret it is remanded for a re-examination of the evidence. Upon re- examination the trial judge decides the case differently. e. Appeal – only issues that can be appealed are decisions about the law by the trial judge. i. Appellant court has 3 options 1. Reversed and remand the case 2. Affirm the trial courts holding 3. Just reverse case and enter judgment for the appealing party a. The trial judge can go beyond this range of discretion and then the Appeals Court can state the trial judge had an abuse of discretion. The trial judge decision was outside the range of reasonableness. Sindle (boy jumping from school bus – false imprisonment case). ii. Be aware of the process of “wearing out your opponent” 1. Court costs: fees for expenses that the courts pass on to attorneys, who then pass them on to their clients or to the losing parties 2. Vosberg – third trial was avoided with upon Putney’s motion, the suit was dismissed based on Vosberg’s failure to pay court costs associated with the prior appeals and to reinstigate the suit in a timely fashion. iii. If no directed verdict, directed motion – just appealing against verdict against you – then the appeals court needs to look at the evidence in view of the light most favorable to the non-moving party [party that the jury found in favor of in the trial court] and assume any conflicts in the evidence are resolved in favor of that party. I.e. in City of Louisville v. Humphrey since the jury found for the ∏, they assume the facts are in the light most favorable to the ∏.

II. The law fact distinction a. Jury is the finder of fact, Judge is the ruler of law b. Negligence cases i. Determination of applicable general standard of care is one for the judge ii. Determination of whether the ∆ failed to meet the standard is a question of fact for the jury. iii. Negligence is labeled “fact” but it is neither law nor fact but rather the application of the laws to the facts. Just call it fact because the jury plays an important role in applying the law to the facts.

Courts in Admiralty

I. United States v. Carroll Towing (negligent care for barge, sink and lose cargo admiralty case). This is not a common law case, but rather tried in court of Admiralty. Originally in England, admiralty cases were heard by a board of admiralty generally composed of Admirals. It has to do with liability on navigable waters. There is no jury, decided by board, and a fighting issue during Revolutionary war because England used admiralty process against colonists because no jury. So US courts – kept the jurisdiction and handed it over to the federal courts (admiralty jurisdiction). Generally would have judges that were “sitting at admiralty” rather than “sitting at law.” The procedure is different for these kinds of cases. In admiralty we’re trying to adjudicate disputes between the vessels. Damages based on relative faults of the two ships – if only one at fault then they pay all damages. If both liable then damages are a matter of degree. This is what is going on here – trying to prove they are both at fault so Carroll Towing doesn’t have to pay all of the damages. a. Good thing about admiralty cases – since no jury we have a full explanation of the how the judge came to his decision. No closed door decision making. b. Admiralty courts have now been meshed into regular courts. This wasn’t the way it was at the time this case was decided.

Punitive Damages

## Come back here w/ Owens v. Illinois

Battery

I. Definition of Battery a. The (1) intentional, (2) unprivileged (without permission, or without defense), and either (3) harmful or offensive contact with the person of another. b. Restatement (Second of Torts):

§13. Battery: Harmful Contact An actor is subject to liability to another for battery if (a) he acts intending to cause a harmful or offensive contact with the person of the other or a third person, or an imminent apprehension (threat) of such a contact, and (b) a harmful contact with the person of the other directly or indirectly results.

§18. Battery: Offensive Contact An actor is subject to liability to another for battery if (a) he acts intending to cause a harmful or offensive contact with the person of the other or a third person, or an imminent apprehension (threat) of such a contact, and (b) an offensive contact with the person of the other directly or indirectly results.

II. Intention a. If you have the intent to do an unlawful act, then the intent is also unlawful (Vosberg). I.e. desire to commit an act. i. Vosberg v. Putney (kick at school, kicker liable) 1. If the intended act is unlawful, then the intention to commit the act must also be unlawful, then the ∆ is liable for the consequences. 2. This was found even though the jury in a special verdict held that the ∆ did not intend the harm. 3. “Thin (or is it thick?) Skull rule” – wrongdoer is responsible for the wrongful act and all resultant harm even if the consequences are unusual and unforeseeable. If not, then the injured person could be hurt under this rule. 4. The code of conduct in a school room (making kick unlawful, ∆ had no license to kick) versus a playground (making the kick lawful). If on a playground engaged in the “usual boyish sports” then it’s a reasonable expectation that someone is going to get kicked. b. Knowledge with substantial certainty (Garrett) i. Garrett v. Dailey (5 ½ year old pull chair from arthritic woman) 1. Knowledge at the time that the act was committed that contact or apprehension would result. 2. Intent can be inferred from knowledge 3. Intention is the either when the act is done for the purpose of causing the contact or apprehension or with knowledge on the part of the actor that such contact or apprehension is substantially certain to be produced. 4. It is not enough that the act itself is intentionally done and this, even though the actor realizes or should realize that it contains a very grave risk of bringing about the contact or apprehension. Such realization may make the actor’s conduct negligent or even reckless but unless he realizes that to a substantial certainty, the contact or apprehension will result, the actor has not that intention which is necessary to make him liable under the rule stated in this section. c. Purpose, motive, desire to harm/offend/violate personal dignity/insult/embarrass/humiliate/create fear or apprehension (Leichtman, national anit- smoking advocate). Stronger than knowledge with substantial certainty. Use K w/sub cert. to determine purpose/motive. d. Transferred intent – if a battery happens to a 3rd and unrelated party. e. “Doctrine of constructive intent” – knowledge based intent? III. Unprivileged – See Defenses, defenses can be non-consensual privilege. IV. Harmful or Offensive Contact a. Harmful b. Offensive i. § 19 – “A bodily contact is offensive if it offends a reasonable sense of personal dignity.” ii. Can have offensive contact that does not cause harm – for example, an un- welcomed kiss. iii. Offensiveness rises out of the circumstances where the contact would occur. Circumstances contribute as to whether the contact is offensive. (Fisher). iv. “For the purpose of causing physical discomfort, humiliation, and distress.” Leichtman v. WLW Jacor Communications, Inc. 1. National anti-smoking advocate had radio talk show host blow smoke deliberately in his face. 2. Remanded for trial court to seriously consider the battery claim as “offensive contact” 3. Ohio common law holds that when smoker intentionally blew cigar smoke in guests face they committed a battery. Tobacco smoke as a “particulate matter” has the physical properties capable of making contact. Ohio Adm. Code 3745-17. 4. The word “purpose” says that the ∆ had desire/motive/intent to blow the smoke in his face. The word “purpose” also has significance in “offensive” contact complaint because “even a dog knows the difference between getting tripped over and being kicked.” If antismoking advocate then he would be offended, but if done w/purpose you’d be likely to be a lot more offended. The ∆’s attitude and purpose enhances the injury to the ∏ or one might so argue. c. Contact i. Contact can be with an extension of the body (Fisher, plate grabbing) 1. This is what distinguished the act in Fisher as being a battery as opposed to an assault (merely a threat). Need contact in battery. What bothered Fisher was what was said when the plate was grabbed. It’s convenient for Fisher’s purposes that there was contact with the plate, because the injury allows the court to give him liability. 2. Hypothetical in class a. Grab plate + insult = bad b. Grab plate before touches + insult = bad c. Grab plate + “we don’t serve patrons on dirty plates” = good d. Restatement (Second) Torts:

§ 13. Battery: Harmful/Offensive Contact. An actor is subject to liability to another for battery if: (a) he acts intending to cause a harmful or offensive contact w/the person of the other or a third person, or an imminent apprehension of such a contact, and (b) A harmful/offensive contact w/the person of the other directly or indirectly results.

V. Minors a. Minors do not necessarily escapes liability for battery i. Vosburg defendant was a minor. ii. Garrett v. Dailey defendant 5 ½ year old held liable. iii. Usually require minors conduct to be willful and malicious b. Some courts have held that minors are not capable of forming the intent that liability requires. Only circumstance where age is of any consequence is in determining what he knew, and there his experience, capacity, and understanding are relevant. c. Hard because in other areas of the law minors are given special protection because of their age. d. Damages i. Collect from the parents, parents can be held liable for negligence. ii. Insurance protects against tort liability, exception being intentional torts. iii. Point: want to force parents to supervise their children and reduce juvenile delinquency.

VI. Defenses – see section entitled “Defenses,” II, “Consent”

Assault

I. Restatement (Second) of Torts:

§21. Assault (1) An actor is subject to liability to another for assault if i. He acts intending to cause a harmful or offensive contact with the person of the other or a third person, or an imminent apprehension of such a contact, and ii. The other is thereby put in such imminent apprehension. (2) An action which is not done with the intention stated in Subsection (1,a) does not make the actor liable to the other for an apprehension caused thereby although the act involves an unreasonable risk of causing it and, therefore, would be negligent or reckless if the risk threatened bodily harm.

§29. Apprehension of imminent and future contact (1) To make the actor liable for an assault he must put the other in apprehension of imminent contact. (2) An act intended by the actor as a step toward the infliction of a future contact, which is so recognized by the other, does not make the actor liable for an assault under the rule stated in § 21.

II. Apprehension of imminent contact a. Must have present ability to carry out threat. (Read v. Coker, paper-stainer lessee case). This is distinguished in the case between the person threatening in “assize time” [i.e. in the future] versus in the present, rolling up sleeves, etc. Might not be as important; see (Beach v. Hancock, gun and rods case). b. Read v. Coker i. ∏ was a paper-stainer, rented from ∆. Couldn’t pay, ∆ take goods. ∆ sold back goods to ∏ at higher price. ∏ can’t afford rent, ∆ pay rent. Form partnership for their mutual benefit. ∆ becomes dissatisfied and dismisses ∏. ∏ refuse to leave, ∆ gather workmen around ∏, tuck up sleeves, ∏ fear men would strike him. ∏ sue for assault. ii. Held: Lower court found for ∏. Appeals Court remanded with instructions that shouldn’t be what the ∏ thought the ∆’s intentions were, should be that there was an attempt + present ability. Evidence does not constitute assault; need more than just threat of violence. c. Perception of the present ability to carry out threat. Discourage assault as a form of intimidation or coercion. Did ∏ reasonably believe ∆ had present ability to carry out the threat? Beach v. Hancock (gun and rods case). d. Beach v. Hancock i. ∏ and ∆ were engaged in a dispute. The ∆ went to his office, brought out a gun, and aimed it at ∏ in a threatening manner. The ∏ was 3-4 rods distant (Rod = 5.5 yards = 16.5 feet). ∆ snapped gun twice at the ∏. The ∏ did not know if the gun was loaded or not. The gun was not loaded. ii. Held: ∆ is guilty of assault. Proper for jury to consider the result if these type of assaults were not punished. iii. Reasoning: One of the goals of the law is that people feel secure against unlawful assaults. Must be reasonable fear we complain of. If this wasn’t punished “the business of the world could not be carried on w/comfort.” Need to punish or else people will assault each other.

III. New tort: Assault Emotional distress (State Rubbish Collectors v. Siliznoff) a. Restatement (Second) Torts

§ 46. Outrageous conduct causing severe emotional distress (1) One who by extreme and outrageous conduct intentionally or recklessly causes severe emotional distress to another is subject to liability for such emotional distress, and if bodily harm to the other results from it, for such bodily harm. (2) Where such conduct is directed at a 3rd person, the actor is subject to liability if he intentionally or recklessly causes severe emotional distress. a. to a member of such person’s immediate family who is present at the time, whether or not such distress results in bodily harm, or b. to any other person who is present at the time, if such distress results in bodily harm.

Comment: “extreme and outrageous” – liability has only been found where the conduct has been so outrageous in character, and so extreme in degree, as to go beyond all possible bounds of decency, intolerable in a civilized community. Not enough that ∆ acted w/intent which is tortuous or even criminal, or intended to inflict emotional distress, or even “malice.” Does not extend to mere insults, indignities, threats, annoyances, petty oppressions, or other trivialities.

b. The ∆ conduct is used as a measure of ∏’s injuries. Use this as proxy since no physical injuries to gage. Question for the jury to exercise own judgment based on personal experience what kind of disagreeable emotions are likely to result from this kind of conduct. Inferring injury from the nature of the conduct rather from the examination of the ∏. (State Rubbish Collectors v. Siliznoff). c. State Rubbish Collectors v. Siliznoff i. Facts: S. take garbage account from member of the association. Rule of association if you take account from member then have to pay. S. intimidated into writing promissory notes. None were paid. Threatened to pay them or harm would come to him in the future. ii. ∆ attorney would be very upset – argued against assault (no present threat, just future threat), jury didn’t get chance to pass judgment on new tort. iii. Held: a cause of action is established when it is shown that one, in the absence of any privilege, intentionally subjects another to the mental suffering incident to serious threats to his physical well-being, whether or not the threats are made under such circumstances as to constitute a technical assault. Regardless of whether is constituted a technical assault, it is still mental suffering. Found another cause of action in history of cases in California – they have allowed the recovery of damages when mental distress causes physical injury. d. Categories of cases that have typically provoked untroubled applications of the tort of intentional infliction of mental upset: i. Debt collection practices ii. Constitutionally protected rights – cesarean section and ∏’s religious beliefs against been seen naked by a man. iii. Mishandling of corpses and related funeral and burial services – one reason why ∏ often succeed in actions against funeral parlors may be the peculiar vulnerability to mental upset of family members in the context of the death and burial of a loved one. Also could follow the deterrence theory: certain classes of cases, the chances of detecting wrongful behavior are seriously impaired and behavior often goes undetected. iv. Conduct of hospitals and health care providers.

False Imprisonment

I. Restatement (Second) Torts

§ 35. False imprisonment (1) An actor is subject to liability to another for false imprisonment if (a) he acts intending to confine the other or a 3rd person within boundaries fixed by the actor, and (b) his act directly or indirectly results in such a confinement of the other, and (c) the other is conscious of the confinement or is harmed by it. (2) An act which is not done with the intention stated in subsection (1,a) does not make the actor liable to the other for a merely transitory [brief duration] or otherwise harmless confinement, although the act involves an unreasonable risk of imposing it and therefore would be negligent or reckless if the risk threatened bodily harm.

II. Needs to be a physical restraint, not necessarily physical force - Whittaker v. Sanford a. Facts: ∏ is member of religions sect, ∆ leader. ∏ say want to leave – gets on boat and goes from Syria to Maine. When get to Maine, ∆ refuse to let her off ship. She eventually gets writ of habeas corpus. Allowed on land during this time – went shopping, picnicked, went to get writ at court. b. Holding: i. Jury found for ∏, Appellate affirmed ii. Damages were too much, does not have the usual humiliation that accompanies false imprisonment cases. iii. Instructions were apt: 1. Must show restraint was physical, not merely moral influence (sense of one being locked in a room). Need physical restraint, not necessarily physical force. 2. If the ∏ was restrained so that she could not leave the yacht by the intentional refusal to furnish transportation as agreed, she not having power to escape other, would be a physical restraint and unlawful imprisonment. c. ∏ got damages for loss of freedom, mobility, and movement. III. Can not be falsely imprisoned in an entire country – Shen v. Leo A. Daly Co. (court held that ∏’s confinement “was to a whole country” and since he was free to move about Taiwan and daily activities not restricted in any way he was not falsely imprisoned. Taiwan is too great an area to be falsely imprisoned.

IV. If ∏ imply consent and does not revel that they feel confined, then not false imprisonment a. Rougeau v. Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. i. Facts: Lawnmowers stolen from ∆ during ∏’s shift as guard. Security manager investigate. With 2 other employees of ∆ take ∏, go to ∏’s house, and search for missing property. Return to plant, ∏ asked to wait in guardhouse, guards instructed to keep him there, ∏ allow to leave when feel ill ~ 30 minutes. ii. Held: Not falsely imprisoned. iii. Reasoning: ∏ need to be totally restrained. ∏ never revealed to anyone that he did not want to stay in guardhouse, thus showing implied consent. b. Faniel v. Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Co i. Facts: Employee suspected of stealing from employer. Accompanied against her will security people to her house. ii. Held: Trial court enters judgment for the ∆ employer notwithstanding a jury verdict for the ∏. iii. Reasoning: No evidence that the ∏, who agreed to accompany the security officers to her home, had yielded to threats, either express or implied, or to physical force. ∏ did not object or ask to leave the car when they took a detour, thus failing to negate her prior consent to take the trip.

V. Damages incurred during escapes (Sindle v. New York City Transit Authority) a. If a ∏ acted unreasonably in its escape, given ∏ has a duty of reasonable care for his own safety in extricating himself from the unlawful detention, not relieved of this duty through false imprisonment. i. It has been held that alighting from a moving vehicle, absent some compelling reason is negligence per se. ii. Thus, if the jury finds that the ∏ was falsely imprisoned but that he acted unreasonably for his own safety by placing himself in a perilous position, recovery for the bodily injuries would be barred and ∆ would not be liable. b. Sindle v. New York City Transit Authority i. Facts: Last day of school, ∏ student, ∆ bus driver. Students being loud led to vandalism. Driver made several stops, investigated the damages, and told students they were going to police station. ∆ closed the doors, pass scheduled stops. Several students jumped from the bus w/o injury. ∏ position to jump, bus hits curb, ∏ falls to street, wheels roll over body causing serious injury. ii. Held: Appeals court reversed and remanded ∆ should be able to submit defense of justification, ∏ should not act unreasonably to get out of false imprisonment.

VI. Statute approach – False imprisonment could be defined in a statute in which case the way to analyze it would be to go through the statute piece by piece. Coblyn v. Kennedy’s Inc. (Massachusetts) a. Facts: ∏ was a 70 year old man went to ∆ store wearing neck scarf. Purchased a sport coat, put scarf in pocket. When he was leaving the store pulled the scarf out of pocket. Goss an employee of ∆ stopped him, demanded where he got the scarf, grabbed him by the arm, and said better go see the manager. Other people look on. ∏ goes back in store; another employee notices him and says he’s cool. As result of emotional upset the ∏ was hospitalized for a heart attack. ∏ claim falsely imprisoned. b. Held: Found for the ∏. c. Reasoning: Goss not reasonably justified in believing ∏ committed larceny. Under statute need reasonable grounds that ∏ commit larceny, reasonable length of time, and reasonable manner of restraint. Since don’t have one then ∏ can recover. Part of the concern here is not giving shop keepers more power than police officers to detail. d. Statute: G.L. c. 231, §94B : In an action for false arrest or false imprisonment brought by any person by reason of having been detained for questioning on or in the immediate vicinity of the premises of a merchant, if such person was detained in a reasonable manner and for not more than a reasonable length of time by a person authorized to make arrests or by the merchant or his agent or servant authorized for such purposes and if there were reasonable grounds to believe that the person so detained was committing or attempting to commit larceny of goods for sale on such premises, it shall be a defense to such action. If such goods had not been purchased and were concealed on or amongst the belongings of a person so detained it shall be presumed that there were reasonable grounds for such belief.” ~ When analyzing need to go through statute piece by piece. i. Reasoning behind statute: motivated by merchant’s organization, keeps with common law prudent and reasonable man standard [just codify common law]. ii. Concern: empowering merchants more than police officers

Defenses

I. Justification a. Justification defense – a defense that arises when the ∆ has acted in a way that the law does not seek to prevent. Traditionally, the following defenses were justifications: consent, self-defense, defense of others, defense of property, necessity (choice of evils), and the use of force to make an arrest, and the use of force by public authority. b. Relevant considerations to the issue of justifications (Sindle v. NY Transit) i. Generally, restraint or detention, reasonable under the circumstances and in time and manner, imposed for the purpose of preventing another from inflicting personal injuries or interfering with or damaging real or personal property in one’s lawful possession or custody is not unlawful. ii. Also, a guardian entrusted with the care or supervision of a child may use physical force reasonably necessary to maintain discipline or promote the welfare of the child.

II. Consent [standard defense for battery] a. The ∆ can only be guided by overt actions (O’Brien v. Cunard Steamship Co, immigration case) i. Consider in connection with the circumstances ii. If ∏’s behavior indicates consent on her part the ∆ is justified in the act, whatever unexpressed feelings of the ∏ may be iii. Test 1. Subjective – what did this ∆ believe? 2. Objective – would a reasonable person in ∆ shoes believe ∏ consented? iv. O’Brien v. Cunard Steamship Co. 1. Facts: ∏ immigrant on passage to Boston where there were strict quarantine regulations. Need vaccination, ship offering it on board. On day of vaccinations ∏ got in line, held out arm, ∆ looked, no mark, he poked her with needle; she didn’t say anything, took the ticket and used it at quarantine. 2. Held: Found for ∆ doctor, appeared as though ∏ immigrant consented. 3. Reasoning: She consented by overt acts. No scar to indicate she had previously been vaccinated. 4. Public health factor also operating here – quarantine if don’t have vaccine. b. Sexual Consent – Consent if female knows the nature and quality of her act. Barton v. Bee Line, Inc. (chauffeur rape case) i. Facts: ∏ (15) suing ∆ (common carrier) for rape. ∆ claims she consented ii. Hold: Female under the age of 18 has no cause of action against a male with whom she willingly consorts if she knows the nature and quality of her act. iii. Reasoning: 1. References Penal Law – crime even if female consents, this is NOT a cause of action, court uses as a basis for civil liability because legislature enacted for reason: virtue of females, save society les and to save society from the ills of promiscuous intercourse. 2. Differentiates between: (1) Society will protect itself by punishing those who consort with females under age of consent; VERSUS (2) When a female knows the nature of her act, and rewording her for her indiscretion. iv. Difference from O’Brien – in O’Brien the ∏ had option of consenting, here its strict liability and consent does not matter. v. Burden of proof – if we look at consent as affirmative defense then burden falls on the ∆. Where the burden falls might determine the outcome of the case. vi. Rules of law: 1. A person who perpetrates an act of sexual intercourse with a female, not his wife, under the age of eighteen years, under circumstances not amounting to rape in the first degree, is guilty of rape in the second degree, and punishable with imprisonment for not more than ten years. 2. A female under the age of 18 has no cause of action against a male with whom she willingly consorts, if she knows the nature and quality of her act. c. Medical Consent Cases i. Restatement (Second)

§ 892D. Emergency Action w/o Consent

Conduct that injures another does not make the actor liable to the other, even though the other has not consented to it if (a) an emergency makes it necessary or apparently necessary, in order to prevent harm to the other, to act before there is opportunity to obtain consent from the other or one empowered to consent for him, and (b) the actor has no reason to believe that the other, if he had the opportunity to consent, would decline.

ii. Bang v. Charles T. Miller Hospital 1. Facts: ∏ (patients) is suing ∆ (doctor) for battery, doctor cut ∏ spermatic cords, and ∏ claims only gave consent to prostate operation. 2. Held: Remanded, question of ∏’s consent is for the jury. 3. Reasoning: Where a physician or surgeon can ascertain in advance of an operation alternative situations and no immediate emergency exists, a patient should be informed of the alternative possibilities and given a change to decide before the doctor proceeds with the operation. 4. Issue: How far does a doctor have to go with what they reveal? iii. Kennedy v. Parrott 1. Facts: ∏ (patients) was diagnosed by ∆ (doctor) is appendicitis, during operation discovered cysts, punctured them, developed phlebitis in the leg. ∏ (Kennedy, patient) is suing ∆ (Dr. Parrott, surgeon) for battery (unauthorized operation) to recover damages for personal injuries. 2. Held: When the ∏ voluntarily submitted herself to defendant for diagnosis and treatment of an ailment, defendant's surgical procedure was, absent evidence to the contrary, presumably either expressly or by implication authorized by plaintiff, as good surgery demanded. 3. Rule: When the patient is incapable of giving consent and no other authority is there to consent for him, consent (in the absence of proof to the contrary) will be construed as general in nature and the surgeon may extend the operation to remedy any abnormal or diseased condition in the area of the original incision whenever he, in the exercise of his sound professional judgment, determines that correct surgical procedure dictates and requires such an extension of the operation originally contemplated. Consent is broad enough to cover what happened here. 4. Unlike Bang Doctor had no notion that a cyst would be on the ovary. iv. Solution – Contract law? 1. Due to problems physicians’ have with medical malpractice suits, some suggest that contracts should be drawn up and signed between physicians and patients ahead of time. 2. Problem with formal agreements – courts need to look behind them to see if patient actually informed and not coerced. Can get out of contract if fraud, coercion. If such contracts are enforced they will also insulate some physicians against unpleasant consequences of their own conduct. v. Distinguished from negligence and battery 1. Battery Kennedy – extends operation beyond boundaries of the consent given. Consent issue. 2. Negligence when doctor fails to inform/explain to the patient the risk of the side effects of a treatment to which the ∏ has consented. d. Custom i. Professional sports, playground, rough activity – if consent to play a sport or rough activity and the act falls outside the custom of the sport then it is tortuous. When customs of the game are such that you are considered to consent to so “rough-housing” then not tortuous. ii. When outside of the game and not custom of the sport then one is considered not to have consented and is still entitled to a tort claim. Hackbart v. Cincinnati Bengals 1. Facts: The ∆ (football player) hit the ∏ (opposing football player) on the back of the neck (against rules of football) when the play was over and the ∏ was on the ground. ∏ says he did not consent to this contact in violation of the rules of football. Trial court said that ∏ consented – public policy – professional football is a species of warfare and physical force is tolerated. Even intentional batteries are beyond the scope of the judicial process. Appeals Court reversed and remanded saying that no law denies the application of tort law to football. 2. Consent comes from consent to play the sport. ∏ saying did not consent to the contact in question. ∆ says he did (defense). 3. Holding: outside of the action of the game and the customs of the game. Jury needs to decide this question. 4. Public policy: if every time someone got hit they would always bring suit. Court doesn’t want to deter people from playing football. iii. See also Vosburg – discussion of playground and “boyish” games – because the boys were away from play and away from the playground they were outside the game and the customs of the game

III. Self Defense a. Restatement (2nd) Torts

§ 63. Self defense by force not threatening death or serious bodily harm (1) An actor is privileged to use reasonable force, not intended or likely to cause death or serious bodily harm, to defend himself against unprivileged harmful or offensive contract or other bodily harm which he reasonably believe that another is about to inflict intentionally upon him. (2) Self-defense is privileged under the conditions states in Subsection (1), although the actor correctly or reasonably believes that he can avoid the necessity of so defending himself, a. By retreating or otherwise giving up a right or privilege, or b. By complying with a command with which the actor is under no duty to comply or which the other is not privileged to enforce by the means threatened.

§ 65. Self-Defense by force threatening death or serious bodily harm (1) Subject to the statement in Subsection (3), an actor is privileged to defend himself against another by force intended or likely to cause death or serious bodily harm, when he reasonably believes that a. The other is about to inflict upon him an intentional contact or other bodily harm, and that b. He is thereby put in peril of death or serious bodily harm or ravishment, which can safely be prevented only by the immediate use of such force. (2) The privilege stated in Subsection (1) exists although the actor correctly or reasonably believes that he can safely avoid the necessity of so defending himself by a. Retreating if he is attacked within his dwelling place, which is not also the dwelling place of the other, or b. Permitting the other to intrude upon or dispossess him of his dwelling place, or c. Abandoning an attempt to effect a lawful arrest (3) The privilege stated in Subsection (1) does not exist if the actor correctly or reasonably believes that he can with complete safely avoid the necessity of so defending himself by a. Retreating if attacked in any place other than his dwelling place, or in a place which is also the dwelling of the other, or b. Relinquishing the exercise of any right or privilege other than his privilege to prevent intrusion upon or dispossession of his dwelling place or to the effect of lawful arrest.

§ 70. Character and extent of force permissible (1) The actor is not privileged to use any means of self-defense which is intended or likely to cause bodily harm… in excess of that which the actor correctly or reasonably believes to be necessary for his protection…

§ 71… an actor who uses excessive force in self defense is liable “for only so much of the force as is excessive” b. Where a ∆ in a civil action attempts to use self defense, he must satisfy the jury not only that he acted honestly using force, but also that his fears were reasonable under the circumstances; and also as to the reasonableness of the means made use of. Courvoisier v. Raymond. i. Facts: ∆ jewelry shop owner’s home was being vandalized by rioters. ∆ took revolver and went to expel intruders from building. They start rioting. Police nearby hear shots and come to scene of the crime. The ∏, police officer, proceeds toward ∆ calling out he is a police officer ad to stop shooting. ∆ shot ∏. Trial Court gave instructions that if ∏ did not assault ∆ then find for ∏. ii. Holding: Remanded for new trial. Need to consider if there is a justification. (1) Honestly believed he was being assaulted, even though he wasn’t; (2) reasonable response to his reasonable fears. iii. Rule of law: Need to establish that if a reasonable person would believe under the circumstances he was being assaulted and the ∆ reasonably believed he was being assaulted. c. Self Defense and Property, Katko v. Briney i. Facts: ∆ own farmhouse in ruin. Series of trespassing and housebreaking events, some theft. ∆ board up home and posted no trespassing signs. ∆ set up “shotgun trap” in north bedroom. Spring gun pointed to hit intruder in the leg. No sign the gun was in there. ∏ enter farm house to steal jars, opened bedroom door, was shot and incurred server injuries. Trial court found for the ∏. ∆ appeals based on jury instructions: can’t use spring fun unless to prohibit felonies and breaking and entering is not a felony; may not use force that will take life or inflict GBI when protecting property; and given can’t use force to take life or inflict GBI, prohibited from setting out ‘spring guns’ for purpose of harming trespassers. Only justifiable use of spring fun is if felony of violence, felony punishable by death, or where trespasser is endangering human life. Appeals Court affirmed. ii. Reasoning 1. Prosser on Torts – “law places higher value on human safety than on property rights.” This statement needs modification: use force between trespasser and petty theft and when landowner would be privileged to use deadly force (threat to his personal safety or home). 2. Rule – no privilege to use force causing death or SBI to repel threat to land or chattels unless threat to ∆’s personal safety as to justify self defense. iii. Distinguished from Courvoisier because not the Briney’s place of dwelling. 1. If just his store then not justified. 2. If Briney was sitting there then different – threat to personal safety and Briney would have ability to distinguish if it was a child, etc. iv. Dissent: Worried about impact in the law and strict liability use of spring-guns. Should have intent attached to it, if ∆ did not intend to kill then not liable for anything other than negligence. Fail to instruct jury on intent. Should be sent to jury because question of ∆’s intention, should not be a blanket ban on the use of spring guns. v. Aftermath 1. Only rarely have ∆’s escaped liability for use of spring guns because the use of such devises is so suggestive of indiscriminate and malicious intent. 2. The maxim that “human life wins over property” is not consistent with every day real life activity.

IV. Necessity a. For allegation of necessity need necessity of the act but also necessity of the act w/respect to ∆’s property. Ploof v. Putnam i. Facts: ∆ owned dock, under charge of ∆’s servant. ∏ sailing on lake with family when storm hit. To save from destruction ∏ moored to ∆’s dock. ∆’s servant unmoored the sloop, drove it into the shore, boat destroyed, ∏ and family injured. ∆ claims that like Katko the ∏ is a trespasser and he had the privilege to remove him from the premises. ∆ demurred, overruled, and appealed. Appeals court affirmed and remanded for full trial, ∏ has to prove alleged facts. ii. Necessity: needs to cover not only the necessity of mooring (the act) but the necessity of mooring to the dock (the act w/respect to the ∆’s property). Should be left to jury w/evidence. ∏ needs to prove that it was necessary to moor to ∆’s dock to save his and his families lives. iii. See this in New Orleans – if we’re talking about water and food as a means to survive would this not satisfy the doctrine of necessity? iv. Doctrine of necessity applies in Mouse’s case – throw casket overboard during a tempest to lighten the boat and save human lives aboard. b. Vincent v. Lake Erie Transportation Co. i. Facts: ∆ moor boat at ∏ dock for purpose of unloading cargo. ∆ had permission to tie up unloaded the cargo finished unloading the cargo storm came, left boat moored, continually maintaining the lines keeping the boat fastened to the dock caused injury to ∏’s dock. Court found would have been imprudent to leave the dock, the ∆ proceeded prudently by maintaining the lines to the dock. ∏ claims trespass – stayed at dock after permission expired. Trial court found for the ∏, ∆ appeals claiming necessity. Appeals court affirms. ii. Rule of Law: If it is an act of God then the ∆ would not be held liable, but the ∆’s maintained the lines and interfered with an otherwise act of god. ∆ preserved their ship at the expense of the ∏ dock. Don’t need to compensate when: 1. Life or property was menaced by an object or thing belonging to the ∏ 2. Act of God or unavoidable accident the infliction of injury was beyond the control of the ∆ 3. Not here: ∆ prudently availed itself to ∏’s property for purpose of maintaining its own more valuable property. iii. Does it make a difference here that we are not distinguishing between life and limb? iv. Dissent: it’s an “act of God” and the storm caused the injury, not the ∆. ∆ had permission to be there, contractual relations. The boat was lawfully in position and master exercised due care. c. Restatement (2nd) Torts combines Ploof and Vincent in §197, recognizing a necessity- based privilege to enter the land of another in order to avoid serious harm to one’s person, land, or chattels, or to those of a 3rd person. Privilege is coupled with duty to compensate for harm caused. § 197 Private Necessity

(1) One is privileged to enter or remain on land in the possession of another if it is or reasonably appears to be necessary to prevent serious harm to

(a) the actor, or his land or chattels, or

(b) the other or a third person, or the land or chattels of either, unless the actor knows or has reason to know that the one for whose benefit he enters is unwilling that he shall take such action. (2) Where the entry is for the benefit of the actor or a third person, he is subject to liability for any harm done in the exercise of the privilege stated in Subsection (1) to any legally protected interest of the possessor in the land or connected with it, except where the threat of harm to avert which the entry is made is caused by the tortuous conduct or contributory negligence of the possessor.

§ 263 Privilege Created by Private Necessity

(1) One is privileged to commit an act which would otherwise be a trespass to the chattel of another or a conversion of it, if it is or is reasonably believed to be reasonable and necessary to protect the person or property of the actor, the other or a third person from serious harm, unless the actor knows that the person for whose benefit he acts is unwilling that he shall do so. (2) Where the act is for the benefit of the actor or a third person, he is subject to liability for any harm caused by the exercise of the privilege.

d. In class hypothetical i. Assume you own both the dock and the boat – you would do whichever action costs less. This is how you would determine what the rational owner would do. Goal is to accomplish the same result with two independent owners. The person sacrificing another’s property for his own needs to compensate. ii. ## come back here and look at these hypothetical with someone else.

Negligence

I. Introduction a. The basis for liability in negligence is the creation of an unreasonable risk of harm to another. There are few activities that do not involve some degree of risk of harm to another. For negligence to be found, the conduct must involve a risk of harm greater than society is willing to accept in light of the benefits derived from that activity (cost- benefit approach) – that is, the risk of harm must be unreasonable. b. Deal with the “reasonable person” standard – amorphous – give it to the jury to decide what a reasonable person is. c. First early case recognizing negligence – Brown v. Kendall i. Facts: Dogs fighting in presence of master, ∆ took stick and beat dogs to break up the fight, ∏ look on from distance, and advance toward dogs, ∆ hit ∏ in eye with stick. ∆ request judge instruct that if both using ordinary care, the ∆ using ordinary care and ∏ wasn’t or if neither using ordinary care then the ∏ cannot recover. Trial judge denied and instructed that if ∆ act not necessary and no duty then liable unless exercise ordinary care “in the popular sense.” If jury thinks ∆ had duty, then burden of proof on ∏, if jury believes unnecessary then burden of proof of ∆. Jury found for ∏. Appeals court remanded for a new trial, the ∆ instructions should have been used. ii. Point of case – one has to act with ordinary care. Difference with what the courts say here and modern negligence is about the burden of proof. The ∏ has to show that the ∆ was negligence, but there is a presumption that the ∏ was using ordinary care and the ∆ has burden of proving ∏ was not using ordinary care to escape liability. Notion move from special duty to general duty. Ordinary care varies with circumstances of the case, once you have circumstances need to look at what the prudent and cautious person would use required by the exigency of the case and to prevent danger.

II. Restatement (2nd) Torts

§ 291: Unreasonableness: How determined: Magnitude of risk and utility of conduct Where an act is one which a reasonable man would recognize as involving a risk of harm to another, the risk is unreasonable and the act is negligent if the risk is of such magnitude as to outweigh what the law regards as the utility of the act or of the particular manner in which it was done.

§ 292: Factors considered in determining utility of actor’s conduct In determining what the law regards as the utility of the actor’s conduct for the purpose of determining whether the actor is negligent, the following factors are important: (a) The social value which the law attaches to the interest which is to be advanced or protected by the conduct (b) The extent of the chance that this interest will be advanced or protected by the particular course of conduct (c) The extent of the chance that such interest can be adequately advanced or protected by another and less dangerous course of conduct.

§ 293: Factors considered in determining magnitude of risk In determining the magnitude of risk for the purpose of determining whether the actor is negligent, the following factors are important: (a) The social value which the law attaches to the interests which are imperiled; (b) The extent of the chance that the actor’s conduct will cause an invasion of any interest of the other or of one of a class of which the other is a member (c) The extent of harm likely to be caused to the interests imperiled (d) The number of persons whose interests are likely to be invaded if the risks take effect in harm.

III. Elements a. Duty b. Breach c. Proximate Cause d. Injury

IV. Duty a. Hand Formula i. Liability depends on whether B < PL, if B< PL then negligent, if B > PL then reasonable, or not negligent. If B = PL then not negligent. So if B ≥ PL then not negligent. Think of verbal definition of negligence – failing to act as a reasonable person in the circumstances would have done. ii. As applied in United States v. Carroll Towing 1. Facts: A bargee left his barge overnight. Barge got into difficulties, broke away, and sank w/cargo in it. Issue of whether the bargee was negligent in leaving the barge. 2. Held: Appeals Court – Reversed and/or remanded – the burden of having employee on board is less than the probability the vessel will break away times the gravity of the injury. Apply new equation. Need to show that ∆, bargee, was not acting with reasonable care upon remand. 3. Formula applied in this case: Owners duty to provide against injuries should be weighed by three variables: 1. (P) Probability the vessel will break away and cause injury in absence of the bargee [always tie probability to the injury that actually happened] 2. (L) Gravity of the resulting injury 3. (B) Burden on the bargee of staying on the barge, taking adequate precautions – the bargee’s freedom. iii. As applied to recent case in the news, tourist vessel capsizes when wake hits the boat, all the people move to one side and force the boat to capsize. 20 people die. Claim company should have had 2 crew members and they only have one. 1. (P) Probability of ship capsizing had they had the second crew member aboard. 2. (L) 20 people died 3. (B) Having second crew member on board iv. Keep in mind that we are looking at this ex post – if looking at it ex ante then looking at the probability of having to pay damages. Not all cases where have to pay out damages. ## see notes. b. Hand formula – with additional condition that need to look at all cases like the case at hand, not just the individual case. Washington v. Louisiana Power and Light Co. i. Facts: Washington was fatally electrocuted when moved radio antenna and made contact with uninsulated electrical wire. Shock had happened a few years earlier. Washington request the insulate or move underground, LPL says only do at Washington’s expense. ∏ sue for wrongful death of Washington, trial court found for ∏, appeals court reversed saying ∆ owed no duty, and supreme court affirmed appeals court. ii. Hand formula: LPL knew there was a possibility of injury, question is whether they created an unreasonable harm. 1. (P) Possibility electricity will escape and cause harm to people – low, Washington learned his lesson the first time, always exercised care. 2. (L) Gravity of resulting loss is extreme – death 3. (B) Burden or relocating or insulating the power line for all people 4. (Burden of relocating or insulating power lines) > (high degree of loss) x (small prob. accident occurring) 5. Focus not just on this case, but all cases like or similar to it. – In just this case then burden of insulating one line would be worth it, but, need to think of all similar cases. Great number of power lines exist, and not overwhelming occurrence of electrocution iii. Rule of law: Need to look at whole system, not just individual case when evaluating the burden. It’s impractical to look at on a case-by-case basis. If you do it for one then everyone is going to want lines insulated. c. Duty, according to the court, is to exercise ordinary care to prevent harm. A duty is owed to everyone. Foreseeability is a primary element in establishing duty. “Everyone” is those that are foreseeably at risk. Weirum v. RKO General, Inc. i. Facts: Radio rock station has contest that rewards first finder of a prize. Have large population of teen listeners. 2 teens were on highway following Disk Jockey’s care; one of them forced the decedent’s car onto center divider and killed him. Trial court found for the ∏, against the radio station. Appeals court affirmed. ii. Procedure points: 1. Duty is a question of law for the court 1. Decided on case-by-case basis 2. General rule that all persons are required to use ordinary care to prevent others from being injured as a result of their conduct such that a reasonable person would conclude they were creating a risk of harm. 2. Foreseeability is a question of fact for the jury iii. Liability: imposed only if the risk of harm resulting from the act is deemed unreasonable – i.e. if the gravity and likelihood of the danger outweigh the utility of the conduct involved. 1. Risk – high speed auto chase causes death 2. Utility – entertainment by radio station iv. Hand formula: Does not use it exactly, but discusses the elements. 1. B foregoing the contest, different kind of contest 2. PL Foreseeable risk of death in auto accident 3. Court says this is undue risk of harm 1. Court makes decision because upholding jury’s decision about how much weight to give to B versus PL. We know this because the jury has decided in favor of the ∏. v. Weigh B and PL inorder to determine if the actor exercised ordinary care. If the actor fails then he breached a duty. In negligence cases we ask (1) did the actor have a duty; and (2) did he breach it? It is under (2) that the formula comes into play, B vs. PL helps to establish if they breached the duty. Everyone is defined by those that are foreseeably at risk. d. Carroll, Washington, and Weirum fall into the Instrumentalist Camp where the goal of negligence law is to achieve the optimal level of accident prevention so that the total costs of accidents and accident prevention will be minimized. e. Trespassers, Licensees, Invitees (See Restatement 218-219) i. Defined 1. Invitee – on land w/permission of possessor. Public or business invite. Owe duty of reasonable care. 2. Licensee – on land with permission of possessor. Privileged to enter or remain on land only by virtue of the possessor’s consent. 3. Trespasser – lowest level of duty, only need to refrain from wanton and willful conduct. Use reasonable care to warn trespassers of hazardous conditions. Higher duty may be necessary for young trespassers under the attractive nuisance doctrine, see below. Children are the exception to the exception, have duty of reasonable care. 4. (Intentional harm Willful and wanton Reckless Gross negligence Negligence Due care) ii. Attractive nuisance doctrine § 339 – Artificial nuisance doctrine A possessor of land is subject to liability for physical harm to children trespassing thereon caused by an artificial condition upon the land if: 1. The place where the condition exists is one upon which the possessor knows or has reason to know that children are likely to trespass, and 2. The condition is one of which the possessor knows or has reason to know and which he realizes or should realize will involve an unreasonable risk of death or serious bodily harm to such children, and 3. The children because of their youth do not discover the condition or realize the risk involved in intermeddling with it or in coming within the area made dangerous by it, and 4. The utility of the possessor of maintaining the condition and the burden of eliminating the danger are slight as compared with the risk to children involved, and 5. The possessor fails to exercise reasonable care to eliminate the danger or otherwise to protect the children. iii. Rowland v. Christian 1. Facts: ∏ was social guest at ∆’s apartment, used a broken faucet handle in the bathroom and sustained injuries. The ∆ was aware but did not warm ∏ of faulty faucet. Trial Court granted ∆’s motion for summary judgment. Appeals Court reversed in favor of the ∏. Case takes place in California, under the civil not common law. 2. Rule: Court eradicates the common law and instates the civil code law that: “everyone is responsible not only for the result of his willful acts, but also for an injury occasioned to another by his want of ordinary care or skill in the management of his property or person, except so far as the latter has, willfully or by want of ordinary care, brought the injury upon himself.” 3. Holding: Where the occupier of land is aware of a concealed condition involving in the absence of precautions an unreasonable risk of harm to those coming in contact with it, the trier of fact can reasonably conclude that a failure to warn or to repair the condition constitutes negligence. The common law classifications of “trespasser, licensee, and invitee” should not influence the standard of care. This court declines the rigid classifications, thinks these lead to injustice. The proper test is embodied in the civil code and is whether in management of his property a man has acted as a reasonable man in view of the probability of injury to others, the status of that man is not determinative. 4. Reasoning: Can depart from ordinary standard of care when balance the following factors: (1) foresee ability of harm to ∏, (2) degree of certainty that the ∏ suffered injury, (3) closeness of the connection between the ∆’s conduct and the ∏’s injury, (4) moral blame attached to ∆’s conduct; (5) policy of preventing future harm; (6) extent of the burden to the ∆; (7) consequences to the community of imposing a duty to exercise care with resulting liability for breach; (8) availability, cost, and prevalence of insurance for the risk involved [talking about 3rd party insurance here, pay out if another gets injured, take risk out of ∆’s hands and spread it out across everyone insured by increased premiums]. These factors are not reflected in common law classification of Trespasser, Licensee, and Invitee. i. Duty: take premises as they find them, possessors only duty is to refrain from wanton or willful injury. 1. Trespasser – enters land of another w/o privilege to do so 2. Licensee – a person like a social guest who is not an invitee and who is privileged to enter or remain upon land by virtue of the possessor’s consent ii. Duty to exercise ordinary care 1. Invitee – business visitor who is invited or permitted to enter or remain on the land for a purpose directly or indirectly connect with business dealing between them. 5. Dissent: L, I, T been developed over many years. Not unreasonable that social guest (licensee, ∏) should be obliged to take premises as host permits them to be. Don’t want homeowners hovering over guests shoulder. Opens the door to potentially unlimited liability.

Restatement 2nd Rowland Invitee Ordinary care Ordinary care Licensee ∆ has reason to know dangerous Ordinary care condition ∏ not know. Trespasser Refrain from willful and wanton Ordinary care? – don’t know this conduct for sure, doesn’t come into play Continuous Trespasser Highly dangerous condition… Ordinary care? Child trespasser Know or reason to know… Ordinary care?

* Movement to eliminate the 3 categories has been followed in other courts as well. Some change law as licensee, but as to willful trespassers they make exceptions and allow for lesser duty of care.

f. Common carriers – most states common carriers are held to have a duty to their passengers higher than that of reasonable care. The “highest” degree of car, “extraordinary care” or “utmost care” because the perceived ultra hazardous nature of the instrumentalities of public rapid transit and the status of passengers being totally dependent on their carrier for safety precautions. g. Guest statutes – lower standard of care owed by operators to their nonpaying guests, only liable for gross negligence. See also Tubbs. i. Insurance companies were proponents of Guest Statute laws – taken advantage of free transport, poor form to sue. ii. Real concern – drivers and passengers have some relationship beyond that, typically known each other before, driver likely to feel bad. Our system is based on both parties making strongest argument; don’t want collusion between driver and passenger w/insurance Company paying out damages. h. Duty to act affirmatively i. When taking precautionary steps and fail to continue to exercise those precautionary steps, there is an affirmative duty to inform others that you have ceased those operative steps. Erie R. Co. v. Stewart 1. Facts: ∏ was passenger in a car, injured when hit by ∆ train. ∆ had watchman at crossing but the watchman was not there. The ∏ had knowledge of this practice and relied upon the absence of the watchman as a sign of safe crossing. Trial court found for ∏, Appeals court affirmed. 2. Holding: When any ∆ takes precaution to prevent injuries to others, others know of this precaution and the ∆ fails to maintain this precaution then the ∆ can be held negligent for breach of this duty. When you’re taking steps to protect people from danger and they are aware of it, you may have a duty to notify them if you cease doing so. 3. Procedural point: Responsible if service is negligently performed or abandoned w/o notice to the fact. i. Negligent performance – issue for the jury ii. Lack of due care (absence of watchman) – negligence appears as a matter of law ii. Failure to Aid and Assist 1. Restatement (2nd) Torts § 314 – “The fact that an actor realizes or should realize that action on his part is necessary for another’s aid or protection does not of itself impose upon him a duty to take such action.” 2. There is no duty to rescue, exceptions: i. Inn keepers ii. Common carriers iii. RR crossing guards (reliance) – Erie iv. Automobile drivers (passenger) – Tubbs v. Employer-employee relationship – Tippicanoe (Held RR Company liable for failing to provide medical assistance to an employee who was injured through no fault of the RR Company, but rendered helpless and thus injuries aggravated.) 2. Tubbs v. Argus - ∏ guest in ∆ car, drive of curb ∏ injured, ∆ left car and did not aid or assist injured ∏. Sue for additional injuries (not covered by guest statute) that incurred when ∆ did not aid or assist. Trial court found for ∆, Appeals court reversed (for ∏). Held: If instrumentality is under control of ∆ then duty of reasonable care to prevent additional injuries. iii. Special Relationship; Pre-existing relationship / Duty to warn; Tarasoff v. Regents of University of California 1. Facts: Podar killed Tatiana Tarasoff. He told ∆ psychologist he intended to kill her two months earlier. Told campus police, they briefly detain, release. Parents suing ∆ for wrongful death. Trial court sustained ∆ demurer. Supreme Court reverse saying that ∆ had duty to warn victim. 2. Held: the defendant therapists' special relationship to patient was extended to victim, and a duty existed to use reasonable care where they had knowledge that patient was going to harm victim. Because have special relationship should be foreseeability. 3. Dissent: Need confidentiality in psychological field. Without it you will deter people from treatment, inhibit patients from full disclosure, and will frustrate successful treatment due to breach in trust agreement. This will create net increase in violence because those who seek treatment will be impaired and cause violence. Only other option is to over- commit to mental institutions. Depriving mentally ill of liberty.

V. Breach

As we think about the elements of neglicence we’ve been looking at questions of DUTY and BREACH. We say the general duty is REASONABLE CARE under the circumstances, and the breach is the failure to adhere to that. This is a pretty amporphous standard. We search for ways to help us give this more specificity. SO, when it’s hard to figure the facts we look at res ipsa loquitor, we many look at statutes for standard of care [determinative, presumptive], and the we look at custom. What these are all trying to do is help us define what constitutes reasonable care/breach under the circumstances.

VI. Cause a. Actual Cause b. Proximate Cause - foreseeability VII. Proximate Cause – Proximate cause issues are different from the negligence issues, even though both involve notions of foreseeability. “The duty element of negligence focuses on whether the ∆’s conduct foreseeably created a broader “zone of risk” that poses a general threat of harm to others… The proximate causation element, on the other hand, is concerned with whether and to what extent the ∆’s conduct foreseeably and substantially caused the specific injury that actually occurred.” a. Circumstantial evidence of causation i. Hoyt v. Jeffers 1. Facts: The ∏ owned a hotel near a steam mill owned by the ∆. Hotel was damaged by fire. ∏ sued claiming fire was caused by sparks from the mill and the mill didn’t have a “spark catcher” and the ∆ was negligent for letting sparks escape. Mill has history of creating fires. Trial court found for the ∏, Supreme Court affirmed saying if jury inferred from the facts that there was causation then the SC will affirm that. 2. Circumstantial evidence: Jury can infer from the evidence, but they are not required to compel from the evidence. Can’t be certain spark caused the fire, but there is enough that the jury could infer the cause was the mill. ii. Smith v. Rapid Transit 1. Facts: ∏ was driving car at 1 am on ∆ bus route. ∏ swerved to avoiding hitting bus, says it was ∆’s bus. There is conflicting evidence; ∏ favor was it was a bus, on the route, same time, same direction. But bus was supposed to be there between 1:15 and 12:45, so some discrepancy. ∏ was in an accident and sued ∆ because she thought it was ∆ bus that caused the accident. Trial court found in favor of the ∆, Supreme court affirmed. 2. ## should lexis this one b. Alternative liability / Joint-several liability / Market share liability i. Terms 1. Joint liability – burden is on the ∆ to allocate damages 2. Severally liable – burden is on the ∏ to prove 3. Joint and severally liable – act in concert or act independently and cause harm, same as joint, the burden is on the ∆ to allocate damages. ii. We know that both the ∆s are negligent here, now we’re dealing with causation. Summers v. Tice 1. Facts: ∏ and ∆s were hunting quail. 3 formed a triangle, ∆ flushed a quail, both ∆’s shot at quail in ∏’s direction. One hit ∏ in the eye, the other in the lip. Don’t know which pellet came from which gun. ∏ argue they are jointly liable, the ∆ argue that they are not jointly and severally liable. Can’t prove which did it. The trial court (w/o jury) found for the ∏, ∏ not contributorily negligent. Appeals court affirmed, they are jointly liable. 2. Held: When two defendants are the possible cause of one harm and the injured party can not point out which defendant caused the harm, the ∆s can both be held jointly [opposed to independently] liable for ∏’s injuries. 3. Reasoning: Both were negligent, can’t determine which ∆ shot him. 4. Rule of law: When two or more persons are the sole cause of one harm, OR, two or more acts by one person are the sole cause of harm, and ∏ has introduced some evidence, then the burden of proof is on the ∆ to prove that the other person or his other act is the sole cause of harm. It would be unfair to deny the injured party redress because can’t apportion damages. Rule should apply when harm has multiple causes, and not merely when ∆ acted together. 5. Independent vers us joint: If independent need to prove which ∆ did it, if joint just prove one of them did it. a. Joint liability – the burden of proof shifts to the ∆ to prove that they were not the one who fired the shot. b. Joint and severally liable – let ∆s apportion the blame amongst themselves. ∏ can recover from either ∆ the entire judgment, each liable for 100% of the judgment. Then would be up to ∆ to seek contribution from others, would be difficult to do in this case because can’t prove which ∆ shot the ∏. 6. Approach toward negligence: Here the court looks at negligence as just breach of duty, other times courts require all 4 elements. iii. Joint and several liability 1. Definitions a. Jointly liable – joined in a single suit, although they need not be b. Severally liable – each liable in full for ∏’s damages, although the ∏ is only entitled to one recovery c. Joint and several liability – where the defendants acted in concert to cause the harm, and where the defendants acted independently but caused indivisible harm. If concerted action, then all are liable for harm caused by one. Example: race cars, only one driver hits a person, both liable. Originally only have joint tortfeasors if act in concert. Now can join for independent acts. Joint and several liability if they act independently, each causing harm to ∏ but impossible to allocate the harm to either ∆’s conduct. d. Today most states provide for contribution among joint tortfeasors. Basic principle of contribution: when two or more persons become jointly or severally liable in tort for the same injury to person or property there is a right to contribution among them. Each make pro- rata share – if make more than that then if pay over you can recover.