1 Scaffolding for Writing an Effective Critique: 9th Grade Support (Sample #2)

Final Paragraph on “The Most Dangerous Game”

Today you are going to participate in a writing workshop. You will receive feedback on your own writing and you will provide feedback on one of your peer’s writing. By the end of the period, you should have ideas on how to improve your paragraph before submitting your final draft.

Step One: Read your paragraph out loud to your partner.

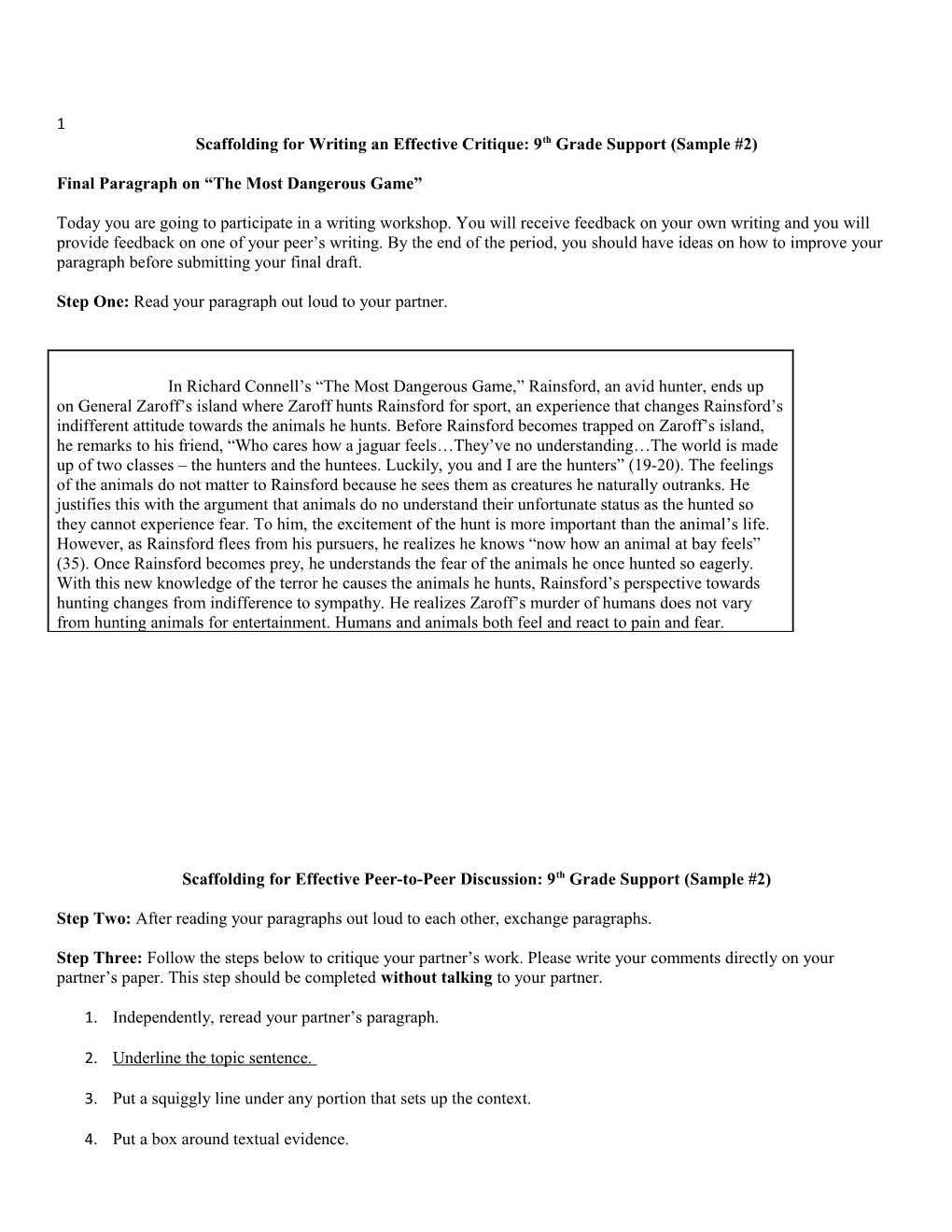

In Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game,” Rainsford, an avid hunter, ends up on General Zaroff’s island where Zaroff hunts Rainsford for sport, an experience that changes Rainsford’s indifferent attitude towards the animals he hunts. Before Rainsford becomes trapped on Zaroff’s island, he remarks to his friend, “Who cares how a jaguar feels…They’ve no understanding…The world is made up of two classes – the hunters and the huntees. Luckily, you and I are the hunters” (19-20). The feelings of the animals do not matter to Rainsford because he sees them as creatures he naturally outranks. He justifies this with the argument that animals do no understand their unfortunate status as the hunted so they cannot experience fear. To him, the excitement of the hunt is more important than the animal’s life. However, as Rainsford flees from his pursuers, he realizes he knows “now how an animal at bay feels” (35). Once Rainsford becomes prey, he understands the fear of the animals he once hunted so eagerly. With this new knowledge of the terror he causes the animals he hunts, Rainsford’s perspective towards hunting changes from indifference to sympathy. He realizes Zaroff’s murder of humans does not vary from hunting animals for entertainment. Humans and animals both feel and react to pain and fear.

Scaffolding for Effective Peer-to-Peer Discussion: 9th Grade Support (Sample #2)

Step Two: After reading your paragraphs out loud to each other, exchange paragraphs.

Step Three: Follow the steps below to critique your partner’s work. Please write your comments directly on your partner’s paper. This step should be completed without talking to your partner.

1. Independently, reread your partner’s paragraph.

2. Underline the topic sentence.

3. Put a squiggly line under any portion that sets up the context.

4. Put a box around textual evidence. 2 5. Put a check in the margin next to any sentence that contains analysis.

6. Put a heart in the margin when the writer connects the story to a theme or an issue in the world.

7. In the space below, write a summary of your partner’s argument.

8. In the “suggestions” box, make any notes about what you think could be changed or improved in the paragraph. This can include punctuation, grammar, and content (thinking/ideas).

Summary of your partner’s paragraph: ______

Suggestions: ______

Summary Reminders. Now that you have finished reading your partner’s paragraph, prepare to write a summary of his/her work. Before you begin, jot down notes on the following: 1. What is the subject of the paragraph: ______

2. Who is the author of the paragraph: ______ 3. What is the topic of the paragraph: ______

4. List 3 main ideas presented in the paragraph:

a. ______

b. ______

c. ______

Now, write a 5-7 sentence summary of the paragraph, including all of the above information. Make sure to write in complete sentences. Here are some sentence starters if you get stuck: 3

In the paragraph entitled ______by ______, the author discusses ______ First, he/she explains ______. Next, he/she describes ______. She/she then discusses ______. Finally, he/she concludes that ______.

Step Four: Your final step in the workshop process is to have a discussion with your partner about your paragraphs. Watch and listen to the teacher and Instructional Associate model this segment of the workshop.

Notes: What did you notice about the ways in which Ms. Ventura and Ms. Placencia spoke to each other? In what ways was their conversation effective? Do you have any suggestions for how to improve their discussion?

Now you try. Here are some sentences starters to help you provide oral feedback to your partner. Please use at least 3 of them in your discussion with your partner.

-One strength in this paragraph is… (be specific! Feel free to use a quote from your partner’s paragraph) 4 -Your argument is effective / ineffective because… -Your topic sentence is strong / weak because… (Consider whether or not the author addressed the prompt) -One specific sentence that could use improvement is… -One idea that could be clarified / better developed is… -One part that confused me was… -Your quote selection was good / need improvement because…

Step Five: Evaluate and Reflect. 1. Rate your discussion on a scale of 1-10: ______2. In what ways did you have a helpful discussion that will better your writing and the writing of your partner?

3. In what ways could your discussion be improved?

Scoring Checklist for “The Most Dangerous Game” Written Critique Part One: Identifying the parts of the paragraph. _____ Underlined the topic sentence _____ Drew a squiggly line under context _____ Boxed textual evidence _____ Checked analysis _____ Drew a heart next to themes/outside world connections Part Two: Writing a summary. _____ Identify author/title of paragraph _____ Identify the subject of the paragraph _____ Identify the main ideas of the paragraph _____ Identify the main conclusion the writer asserts _____ Is clearly written _____ Is well organized Part Three: Making suggestions. _____ Offer at least 1 suggestions for how to improve the content (ideas) of the paragraph _____ Offer at least 2 suggestions for how to improve the grammar and mechanics of the piece 5 6 English IV: Creative Writing Name: ______Flash Fiction Writing Date: ______

You read a whole book of flash fiction over the summer. Or, if you didn’t do your summer reading (or at least not all of it), you should have read the twelve flash fiction stories I gave you in class. Then, you discussed those stories with your peers.

So. You have a pretty good idea what flash fiction is all about, right? Well, if not, here are the specs:

FLASH FICTION is a genre of short story marked by extreme brevity. For the purposes of this assignment, your story cannot be more than 750 words.

Can’t think of where to begin? Perhaps you can be inspired by one of the 80 short stories in Flash Fiction Forward, and loosely “imitate” it, either in style, format, content, or general idea. For example, imitate Tiffany by writing a story from a non-human perspective. Or imitate Currents by writing a story that follows a backward chronology. Or imitate How to Set a House on Fire or To Reduce Your Likelihood of Murder by writing a story using 2nd person perspective (“you”). Or imitate the syntax in Sweet Sixteen or Drawer by writing a story that consists of one or two run-on sentences (yes, your grammar-nerd, former- editor teacher is suggesting you write run-on sentences…). Or imitate the content of The Peterson Fire by writing a story about a sad event that haunts the narrator. Or imitate 00:02:36:58 and write a story about the importance of a single moment. Or write a funny story like The Voices in My Head or My Date with Neanderthal. You can write whatever you’d like, as long as you can explain your story’s connection to one story in the book.

Process, Format, and Length Requirements:

At least 3 drafts: o Draft one = handwritten in class o Draft two = typed, revised, and peer-edited o Draft three = typed and further revised/as good as you can get it without the teacher’s help Typed in a 12 point, legible font Double-spaced No more than 750 words (and it will be a challenge to make it feel complete in so short a space)

Stylistic Requirements:

“…First that the subject of a flash should not be small, or trivial, any more than it should be for a poem, and second that the essence of a story exists not just in the amount of ink on the page—the length—but in the writer’s mind, and subsequently the reader’s” (13). “—a flash fiction should be memorable… --a good flash should move the reader emotionally and intellectually, it should be well written…” (13). The clarity and grace of your story depend on your correct and/or purposeful use of grammar and mechanics. By the 3rd draft (the one I read and edit), there should be minimal errors.

You will eventually write a polished, perfected final draft of this story for your portfolio, so please make sure you save all parts of the process. 7

Process Requirements:

D1 – Get it down. Remember, this is your “shitty” first draft. /10

DUE:

D2+ – Fix it up. Type and double-space it, then make 4 copies for distribution. /10

DUE:

Peer Feedback – Share your D2+ with classmates. Give and get constructive criticism. /45

DUE:

D3+ – Revise it again. Tighten and clean it. Type and double-space it. Turn in the whole process to be teacher/reader-edited. /15 DUE:

Read Aloud—Sometimes it’s easier to critique a piece when it is read aloud. Read to a peer; give/get feedback. /10 To be done in class on:

Author’s Reflection

/10 To be done in class on:

D4+ – Do a final draft, taking the teacher/reader corrections into consideration. Make it your best work. This final draft should be single-spaced for publication. It must fit on one side of one page. Feel free to include a photo/ drawing/ graphic. /20 DUE:

Make 2 copies of the final draft. One goes in your portfolio, stapled on top of all the rough drafts/ writing process. The other goes to Ms. Ventura to be published in a class book.

DUE:

/10

Grand Total: /120 8

English IV: Creative Writing Workshop Protocol

Workshop: As students in high school, you have indubitably participated in peer feedback activities in the past. A creative writing workshop is similar to the activities you have done in the past in that you will read your classmates’ work and provide feedback for them, as they will do in return for you.

Purpose: The purpose of workshop is to receive HELPFUL and RESPECTFUL feedback, both oral and written, from other writers in order to improve your own work.

Letting an author know what is working is as important as what is not. However, saying “I like it. It’s perfect,” is not valuable nor is it constructive. Likewise, negative comments without discussions of why or what might help the author develop his or her ideas are not helpful either.

Process: Steps to Follow for an Effective Workshop Experience The success of a workshop is contingent on the effort and willingness of all group members to participate. Here is a guide to help you with both the individual portion of workshop as well as the group activities.

Step 1: Individual Readings Each member will read each story twice. a. First, read the story without a pen to get an overall sense/feeling of the piece and its direction. b. Reread the story with a pen. Write all over it. Corrects the mechanics, but your primary focus should be content, content, content. c. Write a story critique (directions are included in this packet) to the author at the end of the story or on a separate sheet of paper.

Step 2: The Workshop Come together as a group to discuss the piece. The author of the piece under discussion MUST REMAIN SILENT. Difficult as that may be, it is absolutely necessary. Do not direct questions to the author. Try to figure out the answers to your questions with the other readers. It’s important for the author to hear those discussions, without partaking in them. a. First discuss the basic plot. What’s the story about? What happens in the beginning, middle, and the end? Is it clear? Do you understand: who is involved, what happens, when it happens, where it happens, why it happens, and how it happens? b. Next, discuss the strengths of the piece. What worked? What specific lines/images stuck? What made you laugh, stop, feel, or wonder? What did you admire about the piece or the author’s style? Point to specific sections of the text: scenes, imagery, dialogue, details, etc. Be supportive and interested. This is the “Feel Real Good” stuff. Make sure everyone in the group speaks at least once. c. Finally, discuss possible improvements. You can be honest and constructive without being negative. Pose intelligent, insightful, and careful questions where you are confused. Remember that the author isn’t finished; this is a work in progress. Please keep that in mind as you point out what you may see as bumps in the road. Angry or hurtful commentary is, in no way, acceptable. 9 Remember to use the balm of kindness. *Note: No one should try to write or rewrite another person’s piece.* Unless an author requests it, we should not be suggesting any new major plot lines. Accept the choices an author has made and work with them—try to understand what the author is doing and appreciate rather than undermine his or her author-ity. There is no right or wrong way to discover voice, the creative process, and the magic of how words and ideas go together. Writing takes time and patience and practice. Step 3: Response Allow the author time to speak for the very first time. S/he can clarify, question, explain (defend, some might say), get help, etc. The author may also choose not to speak.

Step 4: Return stories to the author Give the marked up stories and your critique to the author. Now he or she can take it home, read everything that you wrote, and let it all sink in.

Step 5: GROUP HUG! Not optional. It’s good for you.

Step 6: Author’s Reflections and Evaluation of Critique As writers, we must learn to listen, accept, and disregard the evaluations of readers. Using reader comments is an art in itself! Take only what is useful to you. If someone says something that you don’t agree with, fine. Listen and disregard. Obviously, if the majority point out something in agreement, you might want to think about it, but even this is your decision. You are the writer. This is your work. Only you can know what to put in and take out. Accept your own decisions. Trust your own eye and ear. The workshop should be a stimulating, exciting, and helpful resource.

If for any reason you feel upset, confused, or offended, please let me know. You can also share good news with me, too!

Thoughts for everyone: Reading and evaluating others’ work is a great learning device. You will begin to see what works and doesn’t work in your own writing. We’ll see common mistakes and brilliant technique. We are all at different level, but this is not a competition. From the less successful stories you will learn to avoid pitfalls. From the more successful, you see possibilities of where you can go, what you can do. We are all moving forward and getting better by way of practice and process. 10 The process of revision is one in which failure is absolutely necessary to the art. This is why we have REVISION. Once again, writing is a craft that takes time, patience, and practice. I hope that at some point you find yourself in that blissful groove of being immersed in your work in progress.

English IV: Creative Writing Name: ______Critiques: What, Why, How Date: ______Period: __

Pre-write: What is a critique? Why are you asked to write critiques?

The What, Why, and How of Critiquing

What is a critique? ______

Why do we critique? Why should I care how to do this? ______

Characteristics of Writing: Academic Creative 11

Keep in mind: Writing is about communication. No matter what you are planning to do with your future, you will need to be able to think critically, formulate complex ideas, and communicate those ideas. Learning to think critically about literature and providing feedback in a constructive, respectful way is an acquired skill that can go a long way in an array of industries.

How: Use the directions that Ms. Ventura gave you! If all else fails and you find you have nothing to say about the work, go through the list and address each question. Please remember: your critique can include notes on grammar, spelling, and mechanics, but these notes should not be the “meat” of your critique, but rather a very small side note. Your critique should address multiple aspect of the work: form & structure, subject, language use, detail. In poetry, pay attention to line breaks, stanza breaks, rhythm, and figurative language. In prose, consider character development, plot, setting, conflict, symbol, theme, point of view, and other elements of fiction. Poem Notes / Critique My Own Poetry This free verse poem uses running as an extended metaphor to consider the writing A November run process. Each stanza explores a component: the begins like molasses; slow start, finding a sense of rhythm, the thick, slow, my muscles pleasure of words and sounds, the tension of sludge through cold, pacing, the thrill of discovery, the satisfaction of until a half-mile in there is rhythm. having written.

My steps are my meter, I love "the cadence of my body rolls / in iambs" each mile a stanza, and because isn't that true, the alternating of by the fourth, the cadence of my body rolls stressed and unstressed sounds echoing the in iambs. Perfect toe/heel footfall? I am also drawn to the stanza pulse, beats, propulsion. on sound, though not all of the listed elements fall under "onomatopoetics" (fun!) necessarily, I’m driven, by and "soothes soul" is a bit abstract for this Onomatopoetics: dead leaves stanza otherwise filled with concrete and crackle, rustle, crumble to dust physical sensations. under foot, while wind whips hair, stings skin, soothes soul. In stanza five, the poem looks outward and places us in a specific geographical vantage Trails, dusty and dry, rise point, and though I usually applaud a specific into the hills. My breath, grounding of place in poems, this specificity took enjambment in my throat, as lungs me out of the poem, strangely enough. Perhaps it pine for air. And still, I push for is because we want to imagine that we are lonely, unwitnessed glory. running somewhere that can't be so neatly defined when we write. Could the landscape At the peak of speed and hilltop, the trailhead take on a familiar-yet-somehow-also-unfamiliar abruptly ends, a vista of Bay to the east, tone here? Pacific to the west, and Silicon, valleying south beyond the reach of golden gates, The poem enjoys such a nice peak here it seems while reddened, yellowed, oranged trees surround me. a shame to cool it back down to walking and a firm, calm denouement. Here's a question to ask My skin crusts with salt, yourself for revision: what is the most exciting part of running (and writing) for you? What is it 12 as I slow to walk, that you're trying to distill from this experience breath smoothing, mind calmed, for the reader? Try dwelling in that space a little a denouement to while longer; resist the urge to tie the poem up my own poetry. with a neat bow at the end ("a denouement to / my own poetry"). Push against this space for a bit and see what happens in the why realm, now that you've written the how. (WC: 290)

Evolutionarily Speaking Structure:

I run the hills of Huddart Park, in the Santa Cruz Mountains. I like the occasional fallen branch that lies crossways on the path, another obstacle to climb Subject: over or duck under. I like the changing texture of earth under my soles—the points of rocks, stabbing, the crunch of twigs, snapping, the squelch of mud, collapsing. There is the darkness of the forest; even on Figurative Language: the brightest day, the sun cannot overpower the shade of branches, leaf-coated, a thousand arms and ten thousand fingers crisscrossed over a lonely cavern. I like the rise in elevation: trails emerge gradually from Action / What is happening: beneath the trees into sunlight, and sky, until the peak of the trail finally overlooks the Pacific. I can run for hours without seeing another person; my steady breath is rarely interrupted by the courtesy, “Hi,” and my muscles pump until they reach that inevitable wobbly stage, as though there is gelatin inside my skin Language / diction: instead of my body’s complex system of woven fibers. It interests me, the musculoskeletal system, so I would like to be a structural integrationist. “Of course you would,” my father said when I mentioned this in a Other things you notice: meeting with my English teacher. “A structural integrationist. I don’t even know what that is.” “But you don’t have to settle,” Ms. Handler said. “You could be anything. You could go to a good school.” Her fingers rubbed the thin edges of my transcript; dry skin, dry paper, an audible verification of my scholarly potential. “But not if you fail English. You can write the poem or take a zero.” 13 Now, take the ideas you have culled from the excerpt and write a short critique for the author. ______Student Sample: Short Fiction Critique

Hi Miles! Your story is about a guy who’s about to go off to college, and is saying goodbye to all his friends. He’s sad, but knows that he’s going to have a great time at college. You develop that theme (being happy at college) a bit (you repeat it in various forms throughout the piece), but not in a very original way. I think that that theme is an important one to include in any piece about leaving home, but it is cliché; in order for your story to not seem cliché, you should develop your theme not by telling us over and over again that your MC is sad that he’s leaving but excited for the new life ahead of him, but instead by showing us that. For example, when you write “they talked for hours recalling past memories and experiences together,” that’s a good opportunity to include some of those memories, and why the MC is so sad at leaving his friends (really show us that he and his friends are close). This also applies to your whole piece; please do more showing and less telling! Showing us means including more concrete/sensory details, figurative language, and possibly some dialogue, all of which will make your reader much more interested and invested in your story (because as it stands now, your story isn’t quite interesting/original enough to make your reader go “Wow!”). The topic that you’ve chosen (going off to college), while applicable to almost everyone in the class, is a clichéd topic and it will be kinda hard to write your story in an original way (I know you can do it though!). In addition, I felt that your story was somewhat unrealistic; I like that your MC cries and definitely shows emotion, but I didn’t know why he was crying when he was crying; for example, he cries a lot with his friends (“they shared laughs and tears,” and “the final moments with his closest friends were extremely saddening, filled with promises and tears”) but he doesn’t cry when he says goodbye to his family. Is that because he feels closer to his 14 friends than his family, because he has already cried with his family before this story takes place, or is it because of something else (like he’s not going to cry until he gets to college because right now he’s only “thrilled that his parents wouldn’t be around to nag at him to wash his clothes of clean his room”)? One thing that will make your story more interesting and believable is to imagine yourself going off to college; what will it be like for you? When do you think you’ll cry and when will you not? Why will you cry when you do (or don’t)? If you do that, I think you’ll be better able to write your MC and make his actions more believable (and the story more original), and therefore more accessible to the reader. Keep up the good work Miles! Now that you have written a piece of flash fiction, read an overview of workshop protocol, practiced writing a brief critique, and read a student sample of a short story critique, it is time for independent practice. Read your group members’ flash fiction manuscripts, making marginal notes and writing the author a note at the end. The next page has guiding questions to help you with your critique.

Fiction: 1. Description a. Reiterate the subject of the piece. What did you think it was about? b. What are the themes and how are they built? c. What is the purpose of the piece? d. How does the piece use language—tone, diction, figurative language, etc? 2. Global Comments—Most of your comments should be global a. Is the piece doing what you think a short story should do? b. In what ways does the story work? What did you like about it? c. Is the story doing things that are fresh and inventive? Is the story innovative, or does it tread well-worn ground? d. Whose work does the story remind you of? It is important to direct your peers toward authors whose work they might be influenced and inspired by. e. Do you understand the subject matter of the piece? f. Is there a clear conflict, tension, climax, and resolution? g. Does the story use specific and concrete language? Does it avoid cliché? h. Is the story focused, clear, organized, and graceful? i. Does the story SHOW, not tell, information using sensory language and detail? j. Are there images in the story? What are they? Could they be improved? 3. Specific Concerns a. Paragraph breaks—does the author use paragraph breaks appropriately? b. Punctuation and capitalization c. Work choice—can you suggest a more effective work or phrase here or there? Has the author used fresh verb choice? d. Compression—can the story be condensed or cut? e. Consider the flow as it is read. Does anything interrupt your experience as you read? f. Verb tense—this is a common problem. Please pick past or present, and stick to it.

Poetry: 15 Form – Does it look like a poem? What do you notice about how it looks on the page? What kind of poem do you see? (Haiku, elegy, free verse, sestina, sonnet, etc.) Discuss line-breaks, stanza division, shape, enjambment, etc. Rhythm – Does it sound like a poem? Does it have musicality, rhyme, repetition, and/ or interesting sound? Do you like the way the poem sounds aloud? How could the author manipulate language to make the sound more pleasing? Action – What is happening in this poem? What is the “story” behind the poem? Figurative language – Is the language “poetic”? Does it use literary devices to convey emotion? What devices do you notice and how do they contribute to meaning? Emotion/ Meaning – What does the poem make you feel, think, or know? What do you think is the meaning of the poem? What lines have the greatest impact? Why and how do these lines affect you? Discuss the meaning of the title. Do you feel that any part of the poem is overly sentimental/ dramatic? How could the author be more subtle? What could be omitted, clarified, tightened or improved? Consider superfluous or abstract language, format, word choice, etc. How could the writer improve the next draft?

English IV: Creative Writing Small Group Workshop: Facilitator’s Guide

Flash Fiction Assignment For each person’s workshop, one group member will facilitate the discussion to ensure the group addresses each aspect of the piece. This sheet is for you to use when it is your turn to facilitate. Your teacher will provide you with a workshop schedule along with a list of who will facilitate for each group member. Each discussion should last a minimum of fifteen minutes.

Name of the author: ______

Name of facilitator (that’s you!): ______

Names of other group members: ______

Workshop start time: ______Workshop end time: ______

Please discuss all of the following: Description 1. Topic: What did you think the piece was about? 2. Theme: What are the themes? How are they built? 3. What is the purpose of the piece? 4. How does the piece use language? (Tone, diction, figurative language, etc.?) Global Discussion 5. Does the story have a beginning, middle, and end? Is there clear conflict, tension, rising action, climax, and resolution? 6. In what ways does the story work? What are its strengths? 16 7. In what ways is the story fresh and inventive? Is it innovative, or does it border on cliché? 8. Does the story remind you of any other author that you know? Which story from the summer reading do you think this piece is working to emulate? 9. Do you understand the piece? Do you understand the subject, the action, and the meaning? 10. Does the story use concrete language (does it SHOW and NOT TELL)? 11. What images do you see in the story? How can they be improved? 12. Characterization: Are the characters believable? In what ways can the author make them more realistic? Specific Concerns 13. Does the author use appropriate paragraph breaks? 14. Does the author use punctuation, including dialogue tags and quotation marks, appropriately? 15. Word choice: Is the language effective? How can it be improved? 16. Are there areas that can/should be cut to make the story tighter? 17. Does the story flow? Is the story meant to flow, or do believe the author intends to have a particular rhythm? 18. Discuss verb tense. Does the author stick to one tense? Is the chosen tense most appropriate for the action of the piece?

Signature of Facilitator: ______Author’s Reflection: Workshop When you are finished with your peer workshop, you will reflect on the feedback you received from your peers. Please answer the following questions as honestly and thoughtfully as you can.

1. Did you receive useful verbal feedback? Be honest. Be specific. (Give names, if you wish to give special credit to a vocal group member.)

2. Did you receive useful written feedback? Be honest. Be specific. (Give names, if you wish to give special credit to a careful reader.) 17

3. How did it feel to have your short story workshopped? What have you learned about writing, the peer workshop process, your story, yourself?

4. How well do you think you performed in the workshop? Did you share your opinion and offer valid commentary for the authors? How do you think you can improve for next time?

English IV: Creative Writing Name: ______Flash Fiction Read Aloud Date: ______Period: ______

Name of writer: ______

Name of listener: ______

Directions for writer: Sit down next to someone who has not read your story and read it aloud to him or her. Give it voice and breath and conviction. Read the entire thing from start to finish without pausing to fix errors or talk about it. If you notice a mistake while you are reading, simply put a checkmark in the left margin and fix it later. When you are finished reading to your listener, answer the questions below:

Did reading your story aloud help you see ways that you could possibly improve the next draft? If so, how? If not, why not? 18

Directions for listener: As the writer reads his/her flash fiction aloud to you, follow along with your eyes on the paper. Listen actively and attentively while the writer reads. Do not interrupt. If you have questions, comments, compliments, or suggestions, simply put a checkmark in the right margin. When the story is finished, answer (verbally) the following questions:

1. What stuck? What images or parts of the story resonated with you?

2. How did the story make you feel?

3. What questions do you have? Think about parts that confused you or didn’t make sense to you. Did the dialogue sound natural and realistic? Were the descriptions vivid enough for you to picture?

4. Explain the checkmarks you placed in the margins. 19 Oral Participation Rubric 4 (10-9) 3 (8-7) 2 (6-5) 1 (4-0) Checking for Pays focused attention to the conversation as Remains on task Non-verbal cues are limited; appears off-task or Exhibits distracting behavior or completion evidenced through non-verbal cues including during the indifferent to discussion; rarely or ineffectively is disengaged; fails to respond to making eye contact with group members, discussion but responds to other group members’ ideas other group members’ ideas nodding in agreement, taking notes, etc.; non- verbal cues responds effectively to other group members’ are limited; ideas responds appropriately to other group members’ ideas Summarizing Clearly and confidently asserts ideas without Clearly asserts Comments are repetitive, minimal or do not Fails to comment or comments dominating the discussion; uses appropriate and ideas without progress the discussion; transitions are missing are inappropriate or off-topic effective transitions between ideas, able to dominating the or awkward assess fluctuations in the conversations and discussion, adjust as necessary making at least 3 impactful comments; effectively able to transition between ideas Analysis Shows perceptive understanding of the Shows solid Analysis largely repeats others’ ideas, rather Fails to show thoughtful literature/readings, synthesizing the themes of understanding of than contributing new ideas to the discussion reflection of the text the work with the topic at hand; insightfully the explains the relevance of cited evidence, literature/readings, assessing the greater literary significance of the attempting to work as a whole synthesize the themes of the work with the topic at hand; explains the relevance of cited evidence, attempting to assess the literary significance of the work as a whole Outer Circle Thoughtfully and thoroughly completes Completes Partially completes assigned task; may be off- Fails to complete most of Participation assigned task, remaining focused throughout assigned task, task during the discussion assigned task; is off-task or the discussion remaining present disruptive during the discussion throughout the discussion 20 Group Group works together effectively to arrive at Group works Discussion is largely disjointed as members fail Group does not work together; deeper understanding of text; members together to make to build on each other’s ideas (students seem certain voices dominate while encourage one another to speak, drawing out meaning of text; more concerned with making their individual other voices remain silent; multiple voices; members support each other, members attempt points rather than furthering a discussion); conversation may lack civility or even in disagreement to draw in quieter members are at times supportive of one another any sort of unity voices and no one/two members dominate; members are generally supportive and civil

Written Critique Rubric 4 (10-9) 3 (8-7) 2 (6-5) 1 (4-0) Marginal Marginal comments are thorough and specific, Marginal Marginal comments are general, allowing room Marginal comments are Comments offering targeted, constructive feedback that comments are for minimal revision. incomplete, overly general, or will allow for substantial and meaningful specific and missing. revision. targeted, offering feedback that will allow for meaningful revision.

Description Description reiterates the subject of the piece, Description Description briefly references the subject of the Description is missing, overly clearly stating what you think it is about; generally states piece; brief, or inaccurate. what you think the Description asserts the themes and explains how writing is about; Description may assert a theme, but fails to are they built; fully explain how it is built; Description Description explains the purpose of the piece; attempts to assert Description partially explains the purpose of the the themes and piece, or misreads the purpose of the piece; Description explains how the piece uses attempts to 21 language—tone, diction, figurative language, explain how are Description mentions language in the piece but etc. they built; fails to examine how it is used..

Description attempts to explain the purpose of the piece;

Description examines some language in the piece—tone, diction, figurative language, etc. Global Comments Comments are thorough, offering insightful Comments are Comments are selective, and may skip over Comments are overly selective, analysis of the work as a whole; comments thorough, offering pieces of the writing; comments briefly or and fail to consider the piece of consider how the varied pieces of the writing analysis of the inaccurately consider how the varied pieces of writing in its entirety; comments work together to form a cohesive whole. work as a whole; the writing work together to form a whole. remain disjointed, and fail to comments attempt consider how the varied pieces of to consider how the writing work together to form the varied pieces a whole of the writing work together to form a whole. Specific Concerns Comments thoroughly and accurately evaluate Comments Comments evaluate some of the specific Comments fail to address the specific concerns of the piece, including (but accurately concerns of the piece, including (but not limited specific concerns, or offer not limited to) paragraphing, punctuation, evaluate the to) paragraphing, punctuation, diction, flow, and incorrect suggestions for diction, flow, and verb tense. specific concerns verb tense. revision. of the piece, including (but not limited to) paragraphing, punctuation, diction, flow, and verb tense. 22