SUPREME COURT OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY

Case Title: R v Beniamini (No 2)

Citation: [2017] ACTSC 32

Hearing Date: 9 March 2016

Decision Date: 23 February 2017

Before: Refshauge J

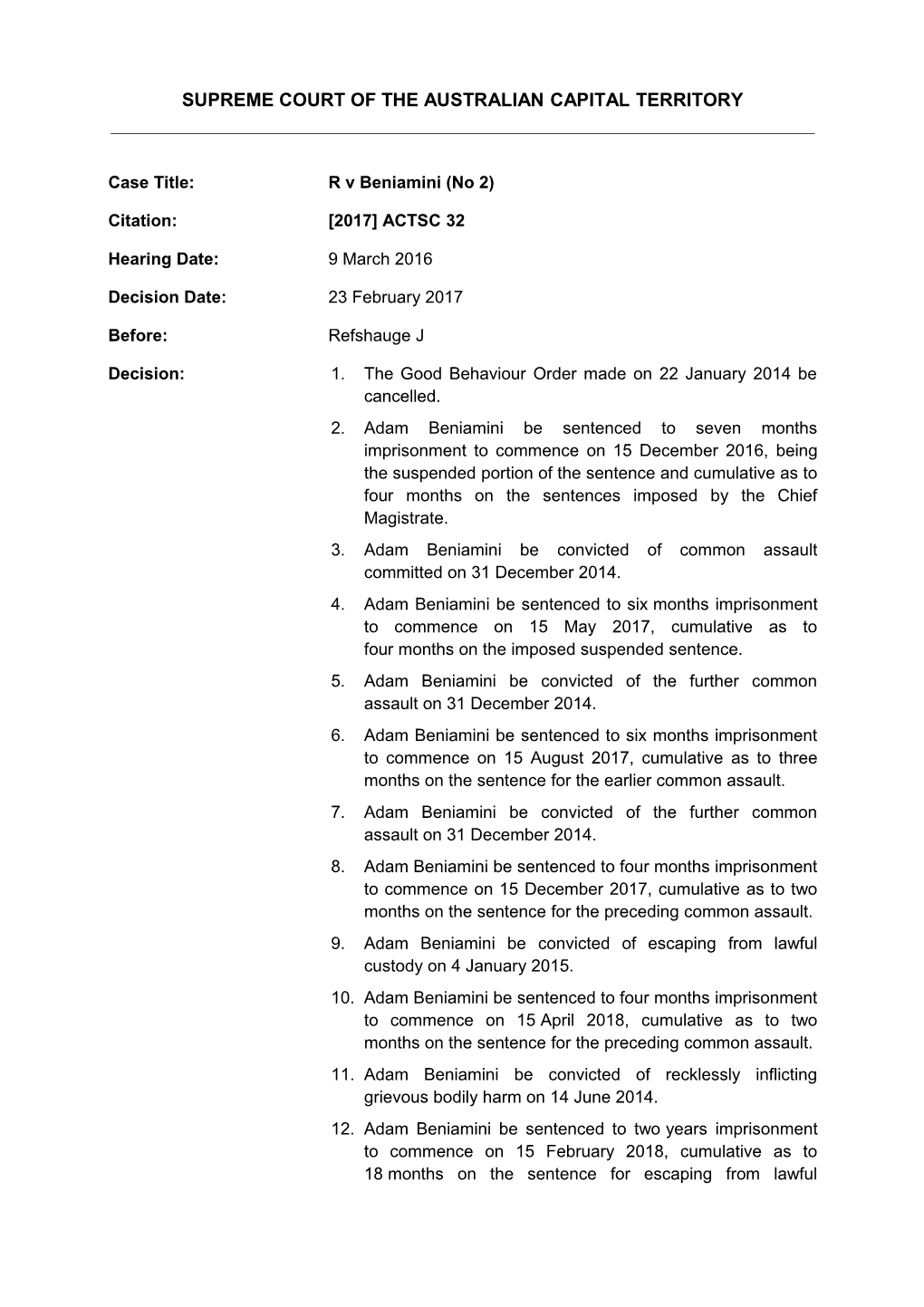

Decision: 1. The Good Behaviour Order made on 22 January 2014 be cancelled. 2. Adam Beniamini be sentenced to seven months imprisonment to commence on 15 December 2016, being the suspended portion of the sentence and cumulative as to four months on the sentences imposed by the Chief Magistrate. 3. Adam Beniamini be convicted of common assault committed on 31 December 2014. 4. Adam Beniamini be sentenced to six months imprisonment to commence on 15 May 2017, cumulative as to four months on the imposed suspended sentence. 5. Adam Beniamini be convicted of the further common assault on 31 December 2014. 6. Adam Beniamini be sentenced to six months imprisonment to commence on 15 August 2017, cumulative as to three months on the sentence for the earlier common assault. 7. Adam Beniamini be convicted of the further common assault on 31 December 2014. 8. Adam Beniamini be sentenced to four months imprisonment to commence on 15 December 2017, cumulative as to two months on the sentence for the preceding common assault. 9. Adam Beniamini be convicted of escaping from lawful custody on 4 January 2015. 10. Adam Beniamini be sentenced to four months imprisonment to commence on 15 April 2018, cumulative as to two months on the sentence for the preceding common assault. 11. Adam Beniamini be convicted of recklessly inflicting grievous bodily harm on 14 June 2014. 12. Adam Beniamini be sentenced to two years imprisonment to commence on 15 February 2018, cumulative as to 18 months on the sentence for escaping from lawful custody. 13. That is a sentence of three years and two months. Together with the sentences imposed by the Chief Magistrate, that is a total sentence of four years and eight months. 14. A non parole period of two years be set to commence on 15 June 2015 and end on 14 June 2017.

Catchwords: CRIMINAL LAW – JURISDICTION, PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – Judgment and punishment – sentencing – sentenced for several offences – recklessly inflicting grievous bodily harm – common assault – domestic violence – multiple breaches of Good Behaviour Orders – significant criminal history – escalation of violent offending – general deterrence – specific deterrence – suspended sentence imposed – totality

Legislation Cited: Crimes Act 1900 (ACT), s 20 Crimes (Sentencing) Act 2005 (ACT), ss 7, 11, 33 Crimes (Sentence Administration) Act 2005 (ACT), s 110

Cases Cited: Beniamini v Craig [2017] ACTSC 30 Beniamini v Storman [2014] ACTSC 2 Grimshaw v Mann [2013] ACTSC 189 Guy v Anderson [2013] ACTSC 5 Oliver (1982) 7 A Crim R 174 Reid v Beniamini (Unreported, Magistrates Court of the Australian Capital Territory, Chief Magistrate Walker, 25 November 2015) R v Bartlett [2016] ACTSC 390 R v Beniamini (Unreported, Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory, Refshauge J, 9 December 2010) R v Beniamini [2014] ACTSC 40 R v Carmody [2016] ACTSC 382 R v Carney [2013] ACTSC 266 R v Curtis (No 2) [2016] ACTSC 34 R v JM [2014] ACTSC 380 R v McGrail [2016] ACTSC 141 R v Olbrich (1999) 199 CLR 270 R v Todd [1982] 2 NSWLR 517 Saga v Reid [2010] ACTSC 59

Texts Cited: Justice François Kunc, “Who are the Recidivists” (2016) 90 Australian Law Journal 847

Parties: The Queen (Crown) Adam Beniamini (Respondent)

Representation: Counsel Mr M Reardon (Crown) Mr R Davies (Accused) Solicitors

2 ACT Director of Public Prosecutions (Crown) Legal Aid (ACT) (Accused)

File Number: SCC 36 of 2016

REFSHAUGE J:

1. In Beniamini v Craig [2017] ACTSC 30, I upheld an appeal against the sentence imposed by the ACT Magistrates Court for certain domestic violence offences. That required Mr Beniamini to be re-sentenced. I shall now do so.

2. At the same time, however, there were two other matters of sentencing which I am required to consider. The first is that the offences the subject of the appeal and, indeed, certain other offences also committed by Mr Beniamini and dealt with in the Magistrates Court, constitute breaches of a Good Behaviour Order I had made when sentencing (and re-sentencing) Mr Beniamini for certain other offences: R v Beniamini [2014] ACTSC 40 (R v Beniamini (2014)).

3. The second matter is that Mr Beniamini has pleaded guilty to an offence of recklessly inflicting grievous bodily harm, for which he is to be sentenced.

4. That offence was committed on 14 June 2014, but Mr Beniamini was not charged until early 2016. It is not entirely clear why it took so long for this offence to be prosecuted.

5. Recklessly inflicting grievous bodily harm is an offence against s 20 of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT) which provides a maximum penalty of 13 years imprisonment.

6. It is appropriate that I deal with that matter first.

The facts 7. Mr Beniamini and his then partner (the victim of the offences the subject of the appeal) attended a social club in Chisholm on Sunday 14 June 2014. At some stage, his partner struck up a conversation with the victim as they both sat in the club’s smoking area. At that time, they were not known to each other.

8. Mr Beniamini saw them in conversation and went up to the victim, whom he believed to be flirting with Mr Beniamini’s partner. He said to the victim words to the effect of, “Don’t go there, mate. She’s with me”. The victim walked away.

9. A short time later, Mr Beniamini saw the victim again speaking to his partner and that she said to him, “Fuck off”. Mr Beniamini went over to the victim, lifted him from his chair by the front of his shirt and struck him in the face with such force that the victim stumbled backwards a number of steps before falling to the ground. The victim managed to get to his feet, but Mr Beniamini approached him and punched him again.

10. Mr Beniamini continued to punch the victim a number of times to the head and body. The victim attempted to protect himself by trying to strike Mr Beniamini, who, however, hit him with such force that he again knocked him to the ground. The two were then separated by other patrons at the club.

11. Police and ambulance officers attended and the victim was taken to The Canberra Hospital where he was treated for his injuries, being:

3 bruising and swelling to the head;

fracture to the right maxillary sinus;

fracture dislocation of the left ring finger. 12. The bruising, swelling, and the fracture to the sinus have healed following the medical treatment. The fracture dislocation to the victim’s finger has had longer term consequences. It will require ongoing treatment which will either be a fusing of the finger or surgery every three to five years to restore function. It has affected his employment.

13. Mr Beniamini was summonsed to appear in Court on 17 February 2016. I was offered no explanation as to why it took over 20 months to bring this matter before the courts. By the time he was required to appear in Court, Mr Beniamini had been in custody at the Alexander Maconochie Centre for 12 months so far as I can tell. There cannot have been any difficulty in identifying him as the assailant nor of finding him to serve process on him. It is relevant to note that the offence pre-dated the offences the subject of the appeal. This delay and the rehabilitation achieved by Mr Beniamini in the meantime is relevant to the sentence I must impose: R v Todd [1982] 2 NSWLR 517 at 519.

14. He entered a plea of guilty on his second appearance in Court, the first at which he was legally represented.

The offence 15. The offence of recklessly inflicting grievous bodily harm is judged by that important yardstick of the maximum penalty set by the legislature, to be a serious offence: Oliver (1982) 7 A Crim R 174 at 178.

16. The Statement of Facts which was tendered without objection included a statement that Dr Vanita Parekh had provided a report to police which stated:

based on a review of [the victim’s] medical records and the [recorded conversation with him] conducted with police that [the victim] had sustained a life threatening injury to his head

17. Despite the lack of objection to the tender, Mr R Davies, who appeared for Mr Beniamini, challenged that assessment. I have to say that, when I read it, I found it difficult to accept.

18. There is no doubt that Dr Parekh is a highly qualified forensic medical officer who has given evidence in Court for the Crown on many occasions. Her evidence has been accepted on many occasions.

19. The material before me was, however, hearsay, and Dr Parekh did not personally examine the victim but relied predominately on the medical records. She did not explain her assessment.

20. In sentencing proceedings, it is clear that matters of aggravation must be proved beyond reasonable doubt. See R v Olbrich (1999) 199 CLR 270 at 281; [27]. There was an opportunity for the Crown to address this issue in accordance with required procedure: R v Carney [2013] ACTSC 266 at [149].

21. The source of my doubt is that the only likely injuries that, it seems, could have been life threatening were the head injuries. The injury to the finger seems an unlikely candidate. The bruising and swelling to the victim’s head, as so described, seem also

4 quite unlikely to be so characterised. Of course, there may have been a risk of brain damage from the trauma causing the bruising, though that seems more likely to have occurred had there been a skull fracture. Even then, that seems unlikely to have been life threatening, though an extremely serious injury. The bruising and swelling may have been caused by, but was not described as resulting from, significant head injury.

22. The cheek bone fracture (right maxillary sinus) is a more likely source of being life threatening if, for example, it had resulted in severe bleeding or interference with airways. There was, however, no suggestion of this.

23. The fact that both those head injuries healed following medical treatment may suggest that they were not so serious. Indeed, the Crown conceded that it was “not the most severe offence within the scheme of reckless ... grievous bodily harm”. That is, the Crown submitted, it is “not a trivial example of grievous bodily harm but it’s accepted as not the most serious”.

24. I have set out in R v Carmody [2016] ACTSC 382 at [51]-[60], some of the relevant factors to be considered when sentencing for this offence. The most significant is, of course, the harm done and I have addressed that above (at [11]-[12], [16]-[23]).

25. There was no premeditation involved here. The degree of recklessness is also important, as explained in R v Bartlett [2016] ACTSC 390 at [29]. The attack was serious and sustained, though it did not continue, it would appear, for any prolonged period.

26. The circumstances of the offence are also important. While not directly a family violence offence in the sense that it was not violence perpetrated on a domestic partner or child, it did arise out of the relationship of Mr Beniamini with his partner and exhibited a possessiveness or jealousy that seems to have the same genesis of attitude that often causes violence to a domestic partner. The conversations between the victim and Mr Beniamini’s partner certainly seemed to be innocuous interactions between them which he viewed through distorted eyes.

27. It is, it appears, a more serious offence because it occurred in a public place: Grimshaw v Mann [2013] ACTSC 189 at [51].

28. The offence was serious but not a particularly serious version of the offence. I have explained the relevant factors.

Subjective circumstances 29. The matters about Mr Beniamini’s personal circumstances are set out in Beniamini v Craig (at [58]-[70]). It is not necessary to repeat them. I take them into account. I shall limit the matters to which I here refer to those that bring the matters up-to-date since the proceedings were before the learned Special Magistrate.

30. These matters will, of course, also be relevant to re-sentencing in relation to the matters the subject of the appeal.

31. Unsurprisingly, Mr Beniamini and his partner are no longer in a relationship; that has now ended.

32. While in custody, Mr Beniamini has completed the Solaris Therapeutic Community Program which I described in R v JM [2014] ACTSC 380 at [26]. He was described as “engaged” in the Program and apparently “participating to a good standard”.

5 33. He has also completed the SMART Recovery Program (as described in R v McGrail [2016] ACTSC 141 at [78]-[80]) and an anger management program, First Steps to Anger Management.

34. I had certificates of completion for these programs. Mr Beniamini has also completed some other programs whilst in custody and these are to his credit. I had certificates showing his participation in a Domestic Abuse Program (which was very appropriate) and Legal Literacy.

35. He has employment available with his father’s tiling business when he is released from custody.

36. It appears that, despite promising to the learned Special Magistrate that he would take action towards his rehabilitation during the period of the Deferred Sentence Order her Honour made (see Beniamini v Craig at [82]), he did not do so, but Mr Beniamini has taken the opportunity while in custody on this occasion to address the issues that contributed to his offending behaviour, especially abuse of alcohol and his anger. This suggests that he does respond to rehabilitation while in a structured environment such as full-time custody.

37. Thus, a relatively lengthy period of significant intervention may be appropriate for Mr Beniamini when he returns from custody into the community. This could be achieved through an Intensive Correction Order under s 11 of the Crimes (Sentencing) Act 2005 (ACT) but, under s 80, such an order may not be served, inter alia, consecutively with a sentence of full-time imprisonment, so Mr Beniamini would not be eligible for such an order.

38. Mr Beniamini has a significant criminal history. In R v Beniamini (Unreported, Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory, Refshauge J, 9 December 2010) (R v Beniamini (2010)), I described it as “unimpressive”. He has added to it significantly to it since then. Including this offence, he has now 39 offences on his record.

39. While 11 are traffic offences, though including more serious offences such as five drink-driving offences and an offence of driving whilst disqualified, he also has six offences of dishonesty on his record. These latter offences, however, apart from an offence of minor theft, date from 2007 or earlier and do not suggest an ongoing problem in that regard.

40. By 2010, he had, other than the offence for which I then sentenced him, four offences of violence on his record, including three offences of common assault. Since then, he has accumulated a further 10 offences of violence which rather justifies my then comment that his prior offences “show a tendency to violence”.

41. The offence for which I was then sentencing him was a more serious offence of assault, namely an assault occasioning actual bodily harm. Since then, he has added seven further offences of common assault, more serious versions of the offence because of the domestic violence context in which they were committed, and I am now to sentence him for the most serious offence of violence which he has committed. This shows a concerning escalation of violent offending which must be addressed.

Breach of Good Behaviour Order

6 42. The final matter with which I have to deal is the breach of the Good Behaviour Order I made on 22 January 2014. There were, in fact, a number of offences which constituted breaches of that order.

43. Those breaches were constituted by the two sets of offences dealt with in the Magistrates Court. The first were three offences of common assault, two offences of property damage and a breach of a bail undertaking, for which he was sentenced to a total term of 21 months imprisonment by the Chief Magistrate: Reid v Beniamini (Unreported, Magistrates Court of the Australian Capital Territory, Chief Magistrate Walker, 25 November 2015). The second were three offences of common assault and one offence of escaping from lawful custody for which he was sentenced to 22 months imprisonment by Special Magistrate Hunter, but which were the subject of the appeal in Beniamini v Craig. While he has to be re-sentenced for the latter offences because I upheld the appeal, the convictions and thus the breaches have not been disturbed. Mr Beniamini, unsurprisingly, admitted the breaches.

44. As stated above (at [41]), the Good Behaviour Order which was breached was made on 22 January 2014, but that was made when an earlier order had likewise been breached. The circumstances are briefly as follows.

45. On 9 December 2010, I convicted Mr Beniamini of assault occasioning actual bodily harm and sentenced him to nine months imprisonment to commence on 29 October 2010 and from 9 December 2010, to be served as to three months by periodic detention, that is until 8 March 2011. On 9 March 2011, the balance of the sentence was then suspended for 12 months and a two year Good Behaviour Order made. See R v Beniamini (2010).

46. The first appeal which I heard from sentences imposed in the Magistrates Court in Beniamini v Storman [2014] ACTSC 2 involved domestic violence offences to which Mr Beniamini pleaded guilty, but in the appeal he challenged the sentences. Those offences were committed during the currency of the earlier Good Behaviour Order made in R v Beniamini (2010).

47. As a result, I cancelled the Good Behaviour Order and re-sentenced Mr Beniamini in respect of those earlier offences. I ordered that he serve the balance of the sentence by periodic detention: R v Beniamini (2014). For the offences the subject of the appeal, I set aside the sentences made by the Magistrates Court and re-sentenced Mr Beniamini to a total of 13 months imprisonment, suspended after six months with a two year Good Behaviour Order: R v Beniamini (2014). It is that Good Behaviour Order that Mr Beniamini breached by the offences dealt with in the Magistrates Court in Reid v Beniamini and Craig v Beniamini. The balance of the sentence of imprisonment which has been suspended is seven months.

48. I am satisfied that these latter offences have breached the Good Behaviour Order I made in R v Beniamini (2014).

49. Accordingly, under s 110 of the Crimes (Sentence Administration) Act 2005 (ACT), I must cancel the Good Behaviour Order. I then have two options: I can impose the sentence then suspended or I can re-sentence Mr Beniamini.

50. As I have pointed out in Guy v Anderson [2013] ACTSC 5 at [83]-[87], there is, in this Territory, no presumption in favour of the imposition of the sentence then suspended.

7 51. Nevertheless, as I also pointed out in Saga v Reid [2010] ACTSC 59 at [99]-[101], the failure to take significant action, including a more appropriate course of action, the imposition of the sentence then suspended has the capacity to undermine the regime of suspending sentences.

52. The authorities have considered a number of matters that a court considering a breach of a Good Behaviour Order must consider before deciding on a response. These have been addressed in R v Curtis (No 2) [2016] ACTSC 34 at [18]-[19], where I said:

18. These include the proportion of the term of the Good Behaviour Order that had been served without breach, any rehabilitation attained by the offender prior to the breach, the nature of the offence which breached the order, including whether it is similar to the offence for which the sentence of imprisonment, then suspended, was imposed, the relative seriousness of the offence so that the imposition of the suspended sentence would be disproportionate to the gravity of the breach offending; and, the prospects of the offender's rehabilitation.

19. Indeed, with re-sentencing, the legislation expressly applies the Crimes (Sentencing) Act 2005 (ACT), to any re-sentencing, which permits all relevant factors on sentencing to be taken into account.

53. It is important, too, to have regard to the actual facts of the offences for which the suspended sentence was imposed and which resulted in the making of the Good Behaviour Order.

54. I will take these factors into account.

55. Although in the Magistrates Court Mr Beniamini was charged with four offences, two were dealt with by fines and these were not the subject of the appeal. The appeal was limited to offences of intentionally causing damage and common assault.

56. I described the facts in Beniamini v Storman at [22]-[34], as follows:

22. By the date of the offences, the relationship between Mr Beniamini and AEL [his then partner] was finally and completely at an end, but Mr Beniamini was denied access to the children of his relationship with AEL, despite the fact that he was making a financial contribution to their support. 23. On the night in question, Mr Beniamini had been drinking alcohol and he was drunk. He went to AEL’s house and banged on the window of the bedroom where AEL was asleep. She awoke and recognised his voice. 24. He said, “Let me in.” AEL replied, “No, it’s the middle of the night.” He said: “Let me in, I just want to come in for five minutes.” She said: “No, I know you’re not going to come in just for five minutes.” 25. He continued to bang on the window, demanding that AEL come outside. 26. AEL then grabbed her mobile phone and got out of bed and walked down the hallway towards the laundry. She heard continued banging on the laundry door and, as she approached it, she saw that it had cracked as a result. A few moments later, the door broke open and Mr Beniamini came in. AEL ran to the lounge room and turned to face Mr Beniamini who was behind her. He then grabbed her around the throat with one of his hands and pushed her backwards onto the couch. 27. Mr Beniamini then began to strangle AEL, saying “You need to help me”. AEL felt his grip tighten and she was unable to speak. After a few moments, he released his grip and AEL said, “You can’t break someone’s door down and expect them to help you”. 28. She walked away from him and he followed her, saying, “You need to help me, you need to help me”. AEL tried on a number of occasions to walk past him, but he

8 stopped her from doing so, making intimidating movements towards her by standing over her and throwing his arms out towards her. 29. AEL sat on the floor in the hallway in an attempt to prevent the situation from escalating and asked him “Why are you doing this?” Mr Beniamini said, “You need to shut your mouth or you’ll cause me to do something bad” and repeated, “You need to help me”. 30. One of AEL’s daughters, however, took AEL’s mobile phone, went into her room and locked the door. She called AEL’s mother. 31. During this time, AEL tried without success to calm Mr Beniamini down, so she got up and walked outside to the front yard. Mr Beniamini followed her, repeating, “You need to help me”. 32. A few moments later, Mr Beniamini put his hand over AEL’s mouth to prevent her from screaming, but AEL broke free and screamed for help. 33. About five minutes later, AEL’s mother arrived and Mr Beniamini calmed down. A short time later, a marked police car, with emergency lights flashing, arrived at the house. Seeing this, Mr Beniamini turned and ran down the street away from the police officers, who pursued him, but lost sight of him as he scaled over fences of surrounding properties. 34. AEL spoke to the police officers; she was visibly upset and showed the red marks around her neck. The police officers also inspected the damaged door, noting that the force used had dislodged the reinforced strike plate. 57. I did not have a Victim Impact Statement, but can accept that the assault must have been very terrifying to the victim.

58. I have set out the facts relating to the two sets of offences which constituted the breach of the Good Behaviour Order in Beniamini v Craig, as to those in Reid v Beniamini at [18]-[22] and those in Craig v Beniamini at [39]-[46]. I take them into account but do not need to repeat them here.

59. I have set out earlier the subjective circumstances of Mr Beniamini which are relevant.

Consideration

60. It seems to me that I should in this case impose the sentence that was suspended in R v Beniamini (2014), namely seven months imprisonment. This is the second time Mr Beniamini has breached a Good Behaviour Order in just over four years; the first was breached a few days over 15 months after it was made, the second just a few days short of five months after it was made. That offence, being the offence of recklessly inflicting grievous bodily harm, was a very serious offence; more serious than any other he has committed since he committed the offence of burglary in 2007.

61. Next, there are now a total of 12 offences which constitute breaches of the Good Behaviour Order. Further, offers of rehabilitation which he made to the various courts have not been fulfilled. By the time of the breaches, he had achieved very little if any rehabilitation; indeed, his offending has become more serious.

62. In my view, the sentence that was suspended, should now be imposed.

Sentencing

63. I have now to sentence Mr Beniamini for the following offences:

9 64. To impose the sentence for common assault committed on 16 March 2012, seven months of which was suspended on 1 February 2014 when he was re-sentenced following his successful appeal. 65. To re-sentence him for the offence of assault committed on 31 December 2014 which, on appeal, I found was manifestly excessive. 66. To sentence him for recklessly inflicting grievous bodily harm on 14 June 2014. 67. In doing so, I must also determine how these sentences, especially the sentences the subject of appeal, should be integrated with each other and with the sentences imposed by the Chief Magistrate to be cumulative or concurrent so as to respect the principle of totality.

Disposition

68. I have regard to the purposes of sentencing set out in s 7 of the Crimes (Sentencing) Act. Clearly the offences of violence and domestic violence, in particular, require a sentence that will deter others from committing such offences as they are serious disruptions to the peace and good order of the community. In particular, the incidence of domestic violence offending in the community seems to be escalating, though that may mean that more incidents are being reported which previously the victims may not have been prepared to do through fear or concern they would not be taken seriously.

69. Mr Beniamini’s continued offending suggests that an element of specific deterrence is also required. That should, however, be moderated by two matters. The first is that he has – some would say finally – decided to participate seriously in rehabilitation and with some apparent success.

70. Secondly, I note that in an editorial in the recent issue of the Australian Law Journal, a reference to a recent report relating to recidivism (which, of course, specific deterrence is designed to prevent) was reported.

71. In Justice François Kunc, “Who are the Recidivists” (2016) 90 Australian Law Journal 847 at 849, the author referred to a recent research report of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research titled, “Violent Criminal careers: A retrospective longitudinal study”, following 26 472 offenders born between 1986 and 1990, though Mr Beniamini falls about three years outside the lower end of this cohort.

72. Nevertheless, a conclusion of the report, which was described as having “significant implications for sentencing policy”, was as follows:

the deterrent effect of prison is very low and that, if rates of violent re-offending are also low, the incapacitation effect of prison on violent offending is likely to be fairly limited. The present results suggest that rates of violent re-offending are low for most offenders. Long periods of incarceration, therefore, are unlikely to do much to bring down the violent crime rate. Justice may demand the imposition of substantial prison terms on those who commit or repeat serious violent offending but the main focus of prevention efforts should be on addressing the underlying causes of violence in our community. Restricting the availability of alcohol, for example, would seem to be a far more effective way of reducing rates of violent crime than the imposition of long prison sentences on those who commit violent offences 73. It is important to denounce Mr Beniamini’s conduct and to impose a just and adequate sentence. It seems to me that this will involve a period of full-time custody. That will also recognise the harm done to the victim.

10 74. I take into account Mr Beniamini’s pleas of guilty. The learned Special Magistrate gave almost a 50 per cent discount for the plea in respect of which I must re-sentence him, but the discount in the other sentences ranged from 25 per cent to 33 per cent. The reason for the very large discount (or, alternatively, the lesser discounts) was not explained.

75. The pleas were entered as follows:

76. for the matters before the learned Special Magistrate, on the third mention; 77. for the matters the subject of the earlier appeal, in one case after a large number of adjournments, but for the other cases relatively early; and 78. for the recklessly inflicting grievous bodily harm – in the Magistrates Court on the third mention. 79. While Mr Beniamini’s criminal history denies him much leniency and his continuing offending is some evidence of a continuing attitude of disobedience to the law, his more recent successes at rehabilitation programs while in custody should be encouraged.

80. The offences were serious; personal violence is always a serious matter and requires an appropriate response to prevent re-occurrence and to show that such behaviour is unacceptable.

81. I note that Mr Beniamini has been in custody since 15 June 2015.

82. I have regard to the matters set out in s 33 of the Crimes (Sentencing) Act. So far as I know them, they are set out in these reasons and the other reasons relating to Mr Beniamini to which I have referred. I take them into account.

83. Having carefully considered all matters, it is clear to me that no other sentence than a sentence of imprisonment is appropriate for these offences.

84. There are, of course, multiple sentences to be imposed. As I have earlier mentioned, the issue of totality is an important one, not only between the offences but also in relation to the sentences imposed by the Chief Magistrate.

85. I have carefully considered the length of each sentence to ensure that Mr Beniamini is not punished twice. I have also considered whether the sentences should be partly or wholly concurrent because, for example, they are part of the same course of conduct. The offences the subject of the appeal were, to a relevant extent, part of the same course of conduct, as I found in Beniamini v Craig at [167]. This has to be reflected in the structure of the sentences.

86. I have then reviewed the length of the term of imprisonment arrived at to ensure that the principle of totality is respected and that the total sentence is adequate to reflect the criminality of the offences committed, but not more than that, and that the total sentence is not excessive, but will leave open the realistic prospect of reform and hope for Mr Beniamini to achieve his goals when he is released into the community.

87. It seems to me, too, that Mr Beniamini requires a significant period of supervision to ensure that the rehabilitation he has achieved in custody is continued and consolidated when he is, as he inevitably will be, released into the community.

11 88. Mr Beniamini, please stand:

89. I cancel the Good Behaviour Order made on 22 January 2014.

90. I impose the sentence then suspended, namely that you be imprisoned for seven months to commence on 15 December 2016, that is to be cumulative as to four months on the sentences imposed by the Chief Magistrate.

91. For the common assault on 31 December 2014 (CC2015/563), I sentence you to six months imprisonment to commence on 15 May 2017 to be cumulative as to four months on the imposed suspended sentence. Had you not pleaded guilty, I would have sentenced you to eight months imprisonment.

92. For the further common assault on 31 December 2014 (CC2015/560), I sentence you to six months imprisonment to commence on 15 August 2017, that is to be cumulative as to three months on the sentence for the earlier common assault.

93. For the further common assault on 31 December 2014 (CC2015/562), I sentence you to four months imprisonment to commence on 15 December 2017, that is to be cumulative as to two months on the sentence for the preceding common assault.

94. For the further common assault on 31 December 2014 (CC2015/561), I sentence you to four months imprisonment to commence on 15 February 2018, that is to be cumulative as to two months on the sentence for the preceding common assault.

95. For the offence of escaping from lawful custody on 4 January 2015 (CC2015/564), I sentence you to four months imprisonment to commence on 15 April 2018, that is to be cumulative as to two months on the sentence for the preceding common assault.

96. For the offence of recklessly inflicting grievous bodily harm (CC2016/11) on 14 June 2014, I sentence you to two years imprisonment to commence on 15 February 2018, that is to be cumulative as to 18 months on the sentence for escaping from lawful custody. Had you not pleaded guilty, I would have sentenced you to two years and eight months imprisonment.

97. That is a total of three years and two months imprisonment. Together with the sentences imposed by the Chief Magistrate, that is imprisonment for four years and eight months in total.

98. I set a non parole period of two years to commence on 15 June 2015 and to end on 14 June 2017.

[His Honour then spoke directly to Mr Beniamini]

99. Mr Beniamini, you really must address your resort to violence. I have made a sentence that is, in effect, four years and nine months in total, and that is a serious sentence for serious serial domestic and other violence offences, which are just not acceptable in our community. You have shown more recently however that you can address some of those matters: the anger management, the drugs, and the alcohol. You have started to make good attempts while you have been in custody to address those matters.

100. The problem for you, however, is that it does not translate into acceptable behaviour when in the community. I do not know whether your attitude to women, or to people in

12 general, is a bad attitude, or whether the drugs or alcohol affect you to the point that you just become truculent. Thus, I think the transition back to the community needs to be under strict supervision for a long period, and therefore for two years and nine months, you will be under supervision.

101. Of course, you know that, on parole, if you breach that parole, and that includes by failing to comply with directions of your parole officer, or by using drugs, getting drunk, or any other further offences, you will be back in custody, and the “street time” does not count. Therefore the two years and nine months is hanging over you for the entire duration of that period.

102. These serious offences cannot be ignored, and the release into the community is not because they are trivial offences or not serious offences, they are, but because you have that long period of imprisonment hanging over you. If you do not take this opportunity and put this relatively short period of serious, violent offending behind you and move on, then you will be in and out of prison for a long time to come.

103. Insofar as I supervise anything to do with you in the future, you should bear in mind that I retire in May, so another judge will have to deal with those matters. They may or may not see something redeemable in you, something able to be rehabilitated, or not. I do not know. So again, I strongly urge you to take this opportunity. You will get out much earlier than you thought you would from the other sentences that you had, but you will still be under supervision and the likelihood of going back to prison if you put a foot out of line is very real.

104. Hopefully, what you have learned in prison, you will be able to translate into the community because you have many qualities and skills that will be useful. Your father needs you; he wants you to take over his business, and you cannot do that while you are in prison.

I certify that the preceding eighty-eight [88] numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of his Honour Justice Refshauge.

Associate:

Date: 27 February 2017

**************** Amendment 11 April 2017 1. In Decision, first page, No 13, the word “nine” before months should be omitted and “eight” substituted.

2. In Paragraph [82] 9 the word “nine” be omitted and “eight” substituted.

13