Who cares about consumer surplus?

Consumer surplus is one of the more simple concepts that economics throws up, but it is quite abstract, and when you add in the stupid diagram, it gets so confusing. It does relate quite closely to your day to day lives however, and ebay is an excellent example of this.

All manner of items can be bought and sold from anywhere in the world. If you cannot find it on eBay then you are pretty unlucky. But what are the economics behind this commercial success? Image source: eBay.

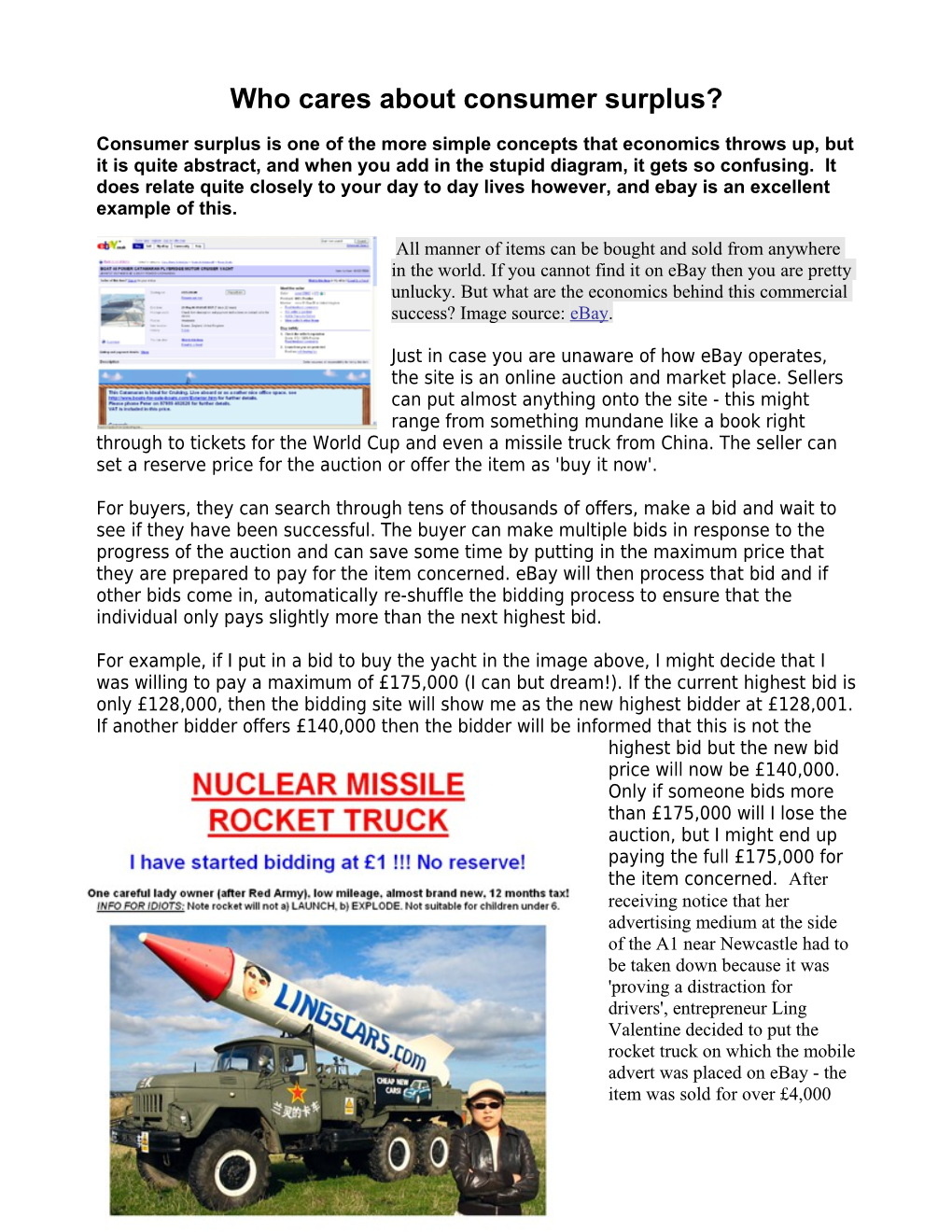

Just in case you are unaware of how eBay operates, the site is an online auction and market place. Sellers can put almost anything onto the site - this might range from something mundane like a book right through to tickets for the World Cup and even a missile truck from China. The seller can set a reserve price for the auction or offer the item as 'buy it now'.

For buyers, they can search through tens of thousands of offers, make a bid and wait to see if they have been successful. The buyer can make multiple bids in response to the progress of the auction and can save some time by putting in the maximum price that they are prepared to pay for the item concerned. eBay will then process that bid and if other bids come in, automatically re-shuffle the bidding process to ensure that the individual only pays slightly more than the next highest bid.

For example, if I put in a bid to buy the yacht in the image above, I might decide that I was willing to pay a maximum of £175,000 (I can but dream!). If the current highest bid is only £128,000, then the bidding site will show me as the new highest bidder at £128,001. If another bidder offers £140,000 then the bidder will be informed that this is not the highest bid but the new bid price will now be £140,000. Only if someone bids more than £175,000 will I lose the auction, but I might end up paying the full £175,000 for the item concerned. After receiving notice that her advertising medium at the side of the A1 near Newcastle had to be taken down because it was 'proving a distraction for drivers', entrepreneur Ling Valentine decided to put the rocket truck on which the mobile advert was placed on eBay - the item was sold for over £4,000 but for Ling, the publicity surrounding the whole thing meant it was worth very much more to her! Image source: eBay. eBay has become an extremely successful company. It was launched in 1995, has over 180 million registered users and in 2005 had revenues of $4.552 billion (£2.446 billion). The site trades more than $1,500 (£806) worth of goods every second. The highest value trade on eBay was a private business jet for $4.9 million (£2.6 million).

(Source of data: eBay Company Overview.)

Theory

The theory underlying this is called consumer surplus but also requires some understanding of markets and the concept of value.

A market brings together buyers and sellers with a view to agreeing a price for exchange. Buyers represent the demand for a product and sellers represent the supply of a product. The medium through which the exchange will take place is the use of money. Both parties to the exchange are looking to get different things from the process.

Buyers will be looking to relate the level of satisfaction or utility that they gain from acquiring the good to the amount of money that they have to give up to gain that utility. We say that the goods have a 'value', which can mean different things to different people. To be able to get some sort of common understanding of what we mean by value, we can use money as the common denominator.

For example, I can relate the value of an item to you by referring to it in money terms: "I think that this pair of trainers is worth $50". Such a statement allows you to be able to make some sense out of my judgement of value. You can relate the $50 to your own circumstances - would you also be willing to give up that amount of money to acquire those trainers? You might respond by saying something like, "You must be joking - I wouldn't give you more than a tenner for them". Such a statement can be translated into economics speak as meaning that value placed on the trainers by you is much less than that placed on them by me.

Money acts as a medium of exchange and allows us all tobe able to compare measures of 'value'. Copyright: Keith Syvinski, from stock.xchng.

If I said to you, "The utility I gain from consumption of these trainers is five times that which you would gain" then the conversation might not get very far! The main point is that we relate the money we have to give up for something as a reference point to whether something is 'worth it' or not. We quickly make some comparisons in our brain as to what the money could buy - yes, it might buy the trainers but it might also be used to purchase a new pair of trousers, some shoes, a night out and so on. When we hand over the money for the good or service, we are saying that we value the utility we are going to get from that good or service at that time higher than anything else that the same amount of money could buy - the opportunity cost.

For producers, a similar principle applies. Suppliers have to consider the cost of supplying the good or service in the first place. The price they want to receive will, preferably, be higher than the cost of supplying that good or service. The higher the price, therefore, the better for the seller. For buyers, it is the other way round - the lower the price the better.

This brings us to demand and supply curves and explains, in part, why they are shaped as they are. The downward sloping demand curve from left to right shows that at higher prices, consumers are less willing to purchase goods than at lower prices. The upward sloping supply curve shows that at higher prices, suppliers are willing to offer more for sale than at lower prices.

Now let's apply some of this discussion to the eBay example. Let us take the example of an England football shirt signed by David Beckham that was auctioned on eBay. The starting bid was £2. Any prospective buyer entering the market will have some idea of what the shirt is worth to them. Let us say that as a prospective buyer, the maximum price I am willing to bid on this shirt is £70. This is saying that I value the £70 I might have to pay for this shirt more than whatever else £70 can buy me at this time.

The bidding, however, is starting at £2. Clearly, if the auction ended and I got the shirt for that price I might be a very happy person: I have managed to acquire something for £2 that I value at £70. Remember that the common denominator, the language of value we all understand (even if we do not agree with it), is money. You can see from the discussion so far that I will be getting some surplus value over and above that which I have to actually pay (assuming that the auction ends at £2). This surplus value will be £68. We can represent this on the diagram below.

The diagram shows the maximum price I am willing to pay to acquire the shirt (£70). If I acquire it for £2 then the shaded area represents all this surplus value. However, the bidding does not stop at £2 - it starts to rise with more and more bidders entering the market. One person puts in a bid of £20 but then another counters this with a bid of £25. What is my position?

I am still willing to be part of the market because the current highest bidder is £25 and my maximum bid price is £70. If I managed to win the shirt at £26, I would still be pleased because I would still have placed a higher value on the shirt than I actually paid. I would be getting surplus value of £44.

The bidding, however, hots up. More and more bidders enter and the price is going up all the time. The end of the auction is drawing near. The top bid is currently £60. I am watching the bidding with a certain amount of anxiety - I keep continuing to enter the bidding and putting in higher and higher prices. Every additional pound that I am bidding is eroding the surplus value that I had. Eventually the bid gets up to £69. I am still willing to make another bid of £70 but what happens if someone else puts in a bid of £71? Do I make a counter bid or do I stick to my original maximum and drop out of the market?

Every time we go shopping we are making choices and expressing statements about 'value' and utility in relation to the price we are being asked to pay. copyright, from stock.xchng.

It is at this point that I am really making decisions 'at the margin' - in many ways, this is what economics is all about. Do I value the extra utility I place on acquiring this good higher than the value of the extra pound I have to bid? If I think, 'yes an extra pound is neither here nor there' then I might well bid - especially if I know the bidding period is nearing its close. But what if my bid continues to be trumped? How much further do I go?

There will, of course, come a point at which I decide that enough is enough and pull out of the bidding if it keeps going up. I then look back at the final winning bid (let us assume that it ended up at £79) and reflect on the process. Should I have gone to £80? Did I cut off my nose to spite my face by pulling out when I did? This process in fact reflects exactly what we do every time we spend some money. The bidding might not be there in quite the same obvious way but every time we make a spending decision we are weighing up the value to us of acquiring the good or service against the price that we are being asked to give up to acquire it (and thus the opportunities foregone). We may not have the protracted process that exists with eBay but the essence is the same.

Think about it: when you go into a shop, there are some things you decide to buy and others you reject. Why do you reject some items but not others? You are likely to be thinking along the lines of, 'It's OK but not worth the money', or, 'It's too expensive'. What we mean by that latter comment is that the utility we will get from the good or service is less than the utility we could get from using that same amount of money in different ways. Of course we do not say all that, but that is what is actually happening.

Now let's turn our attention to the idea of a 'bargain'. Getting a bargain means paying much less for something than we expected or anticipated. In economics terms, a bargain means we get a greater degree of consumer surplus than we expected. The diagram below illustrates this idea again.

Just as we can identify consumer surplus on the part of the buyer, we can look at the seller's side and identify the concept of 'producer surplus'. Imagine I was the person who put the shirt up for sale on eBay. I might think that it is worth around £50. I watch as the bidding process gets going and am happy that the price is gradually working its way up to £50. If it stopped at that level I would be more than satisfied. However, as the bidding pushes the price up even further, I am getting even more satisfied with the likely outcome. If the sale ends at £79, I have gained a surplus value represented by £29 over and above what I would have been willing to accept for selling the shirt.

Producer surplus can be illustrated on the diagram as below. Economics is something that can be very complex and abstract. The basic principles occur day after day, however, and being able to think like an economist and view things the way an economist would view them helps to make these every day events clearer and more understandable. Something like eBay and consumer and producer surplus is just one simple example.

Take a look at the article below taken from the Guardian and answer the questions that follow

Picasso portrait sells for $95m

A portrait by Pablo Picasso depicting the woman he called his "private muse" has sold for $95.2m (£52m), the second-highest amount ever paid for a painting at auction.

Dora Maar au Chat went to an anonymous buyer during the keynote spring auction of Impressionist and modern art at Sotheby's in New York.

The painting almost doubled its pre-sale estimate, putting it within touching distance of the highest price paid for any artwork sold at auction, Picasso's Garcon á la Pipe, which went for more than $104m (£56.9m) in May 2004.

Picasso painted Maar many times during their nine-year affair, which began in 1936 when she was making a name for herself as a surrealist photographer. The pair quickly became lovers, Maar Detail from Picasso' Dora remaining close to Picasso throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s Maar au Chat. Image: and assisting with several of his works, including the monumental AP/Sotheby's mural Guernica. Dora Maar au Chat was completed in 1941, a few years before the couple separated, and was described by Sotheby's as being among the most spectacular of all Picasso's portraits of Maar, depicting her seated in a chair with a small cat perched on the back.

Even so, auctioneer Tobias Meyer admitted he was surprised when the bidding passed $65m.

"The energy in the room was incredible," he told Reuters. "There's just a very clear, strong demand for the kind of intense painting with an emotional pull that the Picasso represents; things that are made for our times."

The buyer remained unidentified, but was present at the back of the salesroom, beating several phone bidders.

The sale comes hard on the heels of another headlining Picasso sale. Le Repos, a portrayal of Olga Khokhlova, his Russian ballerina wife, fetched nearly $35m (just over £19m) at New York rival Christie's on Tuesday.

Also sold at Sotheby's were paintings by Monet and Renoir, Pres Monte Carlo and Fleurs et Fruits - both subject to controversy because they are listed among the possessions of disgraced businessman Dennis Kozolowski. The paintings are being sold to pay fines following Kozlowski's conviction last year for grand larceny.

The sale also set a new world record for a Matisse. Nu Couche Vu De Dos went for $18.5m (£10m), painted in 1927 during Matisse's most accomplished period as a colourist.

Source : http://arts.guardian.co.uk Thuirsday May 4 2006

1. Use a diagram to explain what is likely to have happened to the level of consumer and producer surplus as the bidding for the painting progressed. 2. Do you think the buyer has still gained some consumer surplus despite paying $95 million for the painting? Explain your reasoning. 3. To what extent could consumer and producer surplus represent a measure of welfare in the economy?