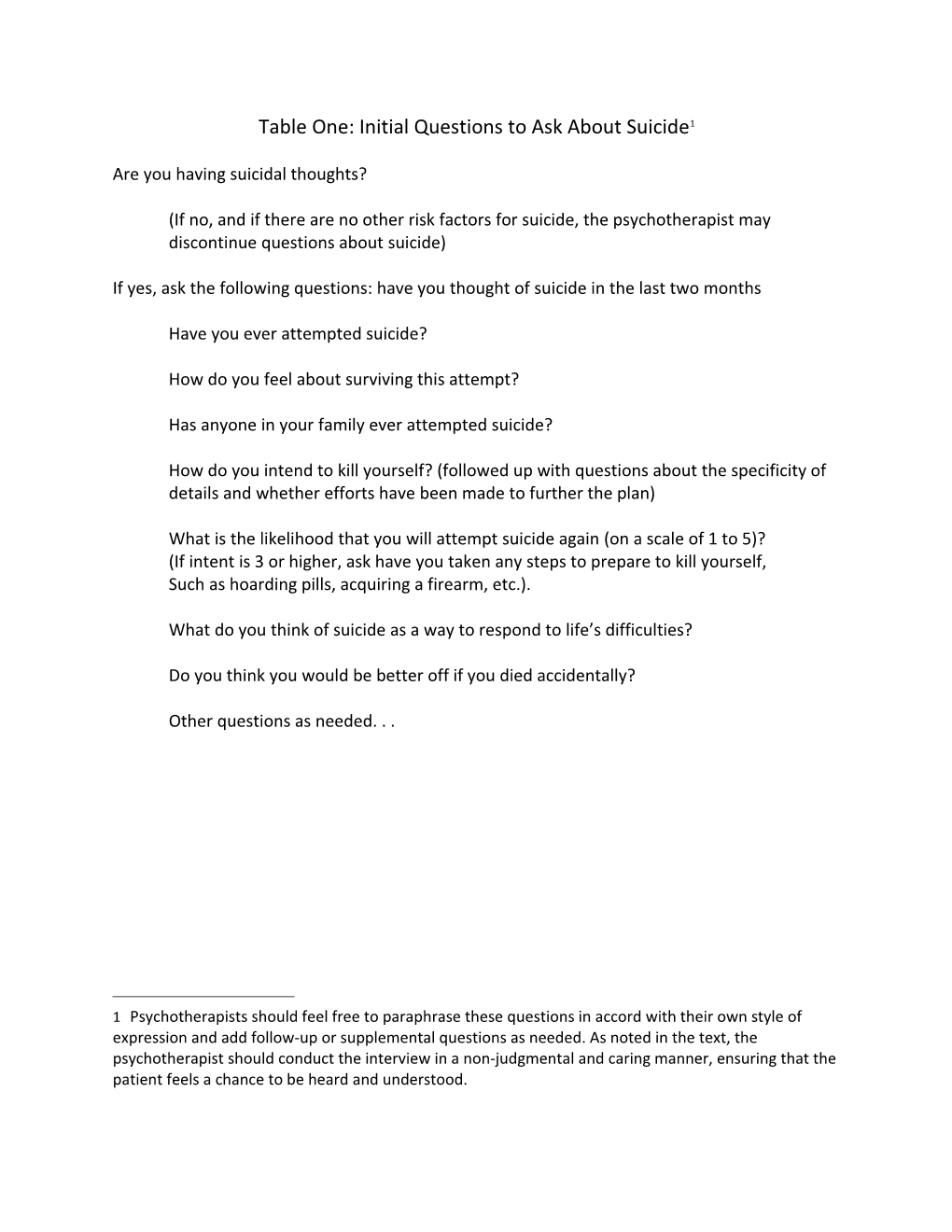

Table One: Initial Questions to Ask About Suicide1

Are you having suicidal thoughts?

(If no, and if there are no other risk factors for suicide, the psychotherapist may discontinue questions about suicide)

If yes, ask the following questions: have you thought of suicide in the last two months

Have you ever attempted suicide?

How do you feel about surviving this attempt?

Has anyone in your family ever attempted suicide?

How do you intend to kill yourself? (followed up with questions about the specificity of details and whether efforts have been made to further the plan)

What is the likelihood that you will attempt suicide again (on a scale of 1 to 5)? (If intent is 3 or higher, ask have you taken any steps to prepare to kill yourself, Such as hoarding pills, acquiring a firearm, etc.).

What do you think of suicide as a way to respond to life’s difficulties?

Do you think you would be better off if you died accidentally?

Other questions as needed. . .

1 Psychotherapists should feel free to paraphrase these questions in accord with their own style of expression and add follow-up or supplemental questions as needed. As noted in the text, the psychotherapist should conduct the interview in a non-judgmental and caring manner, ensuring that the patient feels a chance to be heard and understood. Table Two: Baseline (Static) Factors Concerning Suicide Risk

Age Risk of death increases with age, especially for those over the age of 65

Gender Men complete suicide more frequently, although women attempt it more often

Ethnicity Whites and Native Americans are more likely to die from suicide than Blacks or Asian-Americans

Sexual orientation Minority sexual orientation increases risk especially if combined with bullying or social rejection2

History A history of childhood abuse, or exposure to traumatic events or violence increases the risk of a suicide attempt

Table Three: Acute Factors Increasing Suicide Risk3

2 There is disagreement as to whether sexual orientation or activity is a baseline (static) or acute factor. Nonetheless it should be considered when assessing suicide risk. Some of the information, such as age or gender can be simply observed. Ethnicity or sexual orientation may not be obvious. When gathering information on these and other issues, psychotherapists should ensure that they are interviewing the patient in a nonjudgmental manner and give the patients an opportunity to tell their stories. Thoughts about suicide The risk of a death by a suicide attempt increases as the intensity, duration and frequency of ideation increases. Ideation accompanied by specific plans need to be considered more seriously

Previous attempts The risk of suicide increases with the number of attempts, their recency, and the lethality of the means used.

Psychiatric illness A psychiatric disorder increases the risk of suicide and the risk increases accordingly to the severity of the disorder. These disorders often involve great emotional pain, helplessness, and hopelessness. Impulsivity and addictions also increase the risk of suicide.

Recent stressful events Especially those involving loss of a loved one humiliation, or betrayal. Recent incarceration and financial stressors are risk factors as well.

Medical conditions Chronic pain and functional limitations increase risk, especially when they involve perceived burdensomeness.

Lack of social support Loneliness increases risk, especially when there is thwarted loneliness created out of loss or rejection by valued others or alienation.

Access to means Access to firearms, medications or other means to die from suicide.

Table Four: Factors Reducing Suicide Risk (Protective Factors)4

3 Psychotherapists can add additional questions based on the unique history of the patient or other factors commonly found with the peers of the patients. During the interview process the psychotherapists should ensure that the patients have the opportunities to tell their stories and feel as if they were heard. Religious beliefs or affiliations Many individuals have religious beliefs or worldviews that prohibit suicide.5

Marriage Strong marriages offer substantial social support.

Children Having children may reduce the risk of suicide, especially if a patient loves or value their children. However, the risk of suicide may increase risk if there is post-partum depression or teenage pregnancy. 6

Other supportive networks Could be close friends, or participation in a social group (such as a church).

4 Psychotherapists can add additional questions based on the unique history of the patient or other protective factors commonly found among the peers of the patient. During the interview process the psychotherapists should ensure that the patients have the opportunities to tell their stories and feel as if they were heard.

5 It may be helpful not to look only at speech that uses religious language, but any speech that indicates a center of meaning, or a commitment to a life philosophy that involves some transcendent obligation or commitment on the part of the patient.

6 Commitment to pets may also reduce risk of suicide in some patients. Table Five: Potential Commitment to Treatment Items7

A list of reasons to live

A statement of personal commitment to improve and to adhere to treatment

Situations, activities, or individuals to avoid

Situations, activities, or individuals to cultivate

A list of signs likely to increase dysphoria or suicidal ideation

Coping strategies

Supportive friends or family members

Professional resources

Other items as determined by the patient and psychotherapist

7 Any commitment to treatment or commitment to life document needs to be in a collaborative spirit with the goal of involving the patients in all major decisions. Ideally, it will be an opportunity for them to demonstrate control over their treatment goals and processes. When creating this document, psychotherapists should ensure that they act in a nonjudgmental manner and give the patients a sense that their perspectives are being heard and that their well-being is important to the psychotherapist. Table Six: Assessment and Management Checklist

Assessment

Initial Questions

Do you ask l patients about suicidal thoughts at least once, unless you can identify clinical reasons not to do so?

If a patient indicated suicidal thoughts do you follow up with more detailed questions, such as previous suicide attempts, their thoughts about surviving such attempts, a history of suicide attempts in their family, etc?

Did you assess passive thoughts of death?

Unless a patient indicated very low suicidal ideation or intent and/or does not have other high risk factors, do you conduct a thorough suicidal evaluation?

Is the interview conducted in a caring and nonjudgmental manner?

Detailed Suicidal Review

When conducting a more detailed suicide assessment, do you gather systematic data on the risk and protective factor for the patient?

Do the patients feel that they had a chance to tell their stories?

Does the patient have a sense that you care about them and their well-being?

Screening Instruments

When conducting a more detailed suicide assessment, do you use a screening instrument to further assess suicide risk?

Management and Treatment

Do you avoid the myths of suicide (e.g. “if patients really want to do it, there is nothing I can do to stop them?”8, “patients with borderline personality disorders cannot be treated effectively,” “patients who talk about suicide never really attempt it,” etc.

8 This myth is especially pernicious because it may lead to helplessness or passivity on the part of the psychotherapist. On a superficial level it is literally true, but it is also very misleading. Effective psychotherapist can greatly reduce the risk of a patient dying from suicide. Did you consider the four “Ms” of management (motivation, medication, means restriction, and monitoring) ? Do patients feel involved in the process?

Do you avoid falling prey to the “myths of suicide” while you develop the management and intervention strategies?

Do you periodically assess for suicidal risk throughout treatment? Do you consider redundant sources of information?

Do you consider breaking confidentiality or involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations only when necessary to save a life and as a last resort?

Does your assessment and management of patients take into account special factors such as the co-existence of a serious personality disorder?

Do you consider using treatments that have empirical or professional support for their effectiveness?

Do you communicate well with other treatment providers and family members, if indicated?

Do you consult when necessary?

Do you document treatment decisions thoroughly and with transparency?

Do you use the prompt list if treatment appears stalled? Table Seven: Ten Question Prompt List

Patient Collaboration (What Does the Patient Say?)

YES ___ NO ___ 1 .Does the patient think you have a good working relationship?

YES ___ NO ___ 2. Do you and your patient share the same treatment goals?9

YES ___ NO ___ 3. Does the patient report progress in therapy?10

YES ___ NO ___4. Does the patient want to continue in treatment? 11 If so, does the patient see a need to modify treatment?

YES____NO___5. Does the patient believe that the risk of suicide is decreasing?

Additional Reflections (What Do You Think About the Patient?)

YES ___ NO ___ 6. Do you believe you have a positive working relationship with your patient? (Does he or she trust you enough to share sensitive information and collaborate?)12

9 Do you understand your patient’s goals and how he or she expects to achieve them? How do they correspond to your goals and preferred methods of treatment? If they differ, can you reach a compromise? Does the patient buy into treatment ? Did you document the goals in your treatment notes ? What did the patient say was particularly helpful or hindering about therapy? Have you incorporated your patient’s perceptions into your treatment plan?

10 Do you agree on how to measure progress (self-report, reports of others, psychometric testing, non- reactive objective measures, etc.)?

11 If yes, why?

12 Can you identify what is happening in the relationship to prevent a therapeutic alliance ? Does the patient identify an impasse? Do your feelings toward your patient compromise your ability to be helpful ? If so, how can you change those feeling ? Have you sought consultation on your relationship or feelings about the patient ? If so, what did you learn? YES ___ NO ___ 7. Is your assessment of the patient sufficiently comprehensive?13 Do you need to obtain additional information?

YES ___ NO ___ 8. Do unresolved clinical issues of significant concern impede the course of treatment (such as Axis II issues, possible or minimization of substance abuse, or ethical concerns)?

YES ___ NO ___ 9. Does the patient need a medical examination?

Documentation

YES ___ NO ___ 10. Have you documented appropriately?

Other Questions?

13 Have you reassessed the diagnosis or treatment methods using the BASIC ID, MOST CARE, or another system designed to review the presenting problem? Are you sensitive to cultural, gender- related status, sexual orientation, SES, or other factors? What input did you get from the patient, significant others of the patient, or consultants? Appendix A: Additional Resources

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. http://www.afsp.org/

American Psychiatric Association. (2003). Practice guidelines for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160 (Suppl. 11). Also available online at http://www.stopasuicide.org/downloads/Sites/Docs/APASuicideGuidelinesReviewArticl e.pdf

National Institutes for Health. Suicide Prevention. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/suicide-prevention/index.shtml

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. http://www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

Suicide Prevention Resource Center. http://www.sprc.org/

The Jed Foundation. https://www.jedfoundation.org/

Recommended Books

Bongar, B., & Sullivan, G. (2013). The suicidal patient: Clinical and legal standards of care. (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bryan, C. J. (2015). Cognitive behavior strategies for preventing suicidal attempts. NY: Routledge.

Jamison, K. R. (2000). Night Falls Fast: Understanding suicide. New York: Random House.

Jobes, D. (2016). Managing suicide risk (2nd Ed.). NY: Guilford.

Joiner, T. (2005). The myths of suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McKeon, R. (2009). Suicidal behavior. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe & Huber. Appendix B: Examples of Screening Instruments

Columbia Suicide Screening Rating Scale: http://www.cssrs.columbia.edu/ It is free. The website reviews the different versions. Brief training videos are available.

Safe-T (Suicide Assessment Five Step for Triage) http://store.samhsa.gov/product/Suicide-Assessment-Five-Step-Evaluation-and-Triage-SAFE-T- Pocket-Card-for-Clinicians/SMA09-4432 It is free and includes an option of a mobile app; contains management recommendations

Suicide Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/SBQ.pdf it is free and brief—only 4 questions

Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation Copyrights for sale by Pearson at http://www.pearsonclinical.com/psychology/products/100000157/beck-scale-for- suicide-ideation-bss.html

Beck Hopelessness Scale Copyright for sale by Pearson at http://www.pearsonclinical.com/psychology/products/100000105/beck-hopelessness- scale-bhs.html

Suicide Ideation Questionnaire Copyrighted, available from PAR; http://www4.parinc.com/Products/Product.aspx?ProductID=SIQ References

Berman, A., & Silverman, M. (2014). Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation Part II: Suicide risk formulation and the determination of levels of risk. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 44, 412-441.

Bryan, A. O., Theriault, J. L., & Bryan, C. J. (2015). Self-forgiveness, posttraumatic stress, and suicide attempts among military personnel and veterans. Traumatology, 21, 40-46.

Centers for Disease Control. (2016). Ten leading causes of death by age group United States. Retrieved f rom http://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc- charts/leading_causes_of_death_age_group_2014_1050w760h.gif

Chemtob, C., Bauer, G., Hamada, R., Pelowski, S., & Muraoka, M. (1989). Patient suicide: Occupational hazard for psychologists and psychiatrists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 20, 294-300.

Cramer, R. J., Johnson, S. M., Rausch, E. M., McLaughlin, J. & Conroy, M. A. (2013). Suicide risk assessment training for psychology doctoral programs: Core competencies and a framework for training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 7, 1-11.

Curtin, S. C., Warner, M., & Hedegaard, H. (2016). Increase in suicide in the United States 1999-2014. NCHS data brief, no. 241. Hyattsville, MD. National Center for Health Statistics.

Czyz, E., Horwitz, A. G., & King, C. A. (2016). Self-rated expectations of suicidal behavior predict future suicide attempts among adolescent and young adult psychiatric emergency patients. Depression and Anxiety, 33, 512-519.

Dazzi, T., Gribble, R., Wessely, S., & Fear, N. T. (2014). Does asking about suicide and related behaviors induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychological Medicine, 44, 3361- 3363.

Edwards, S. J., & Sachman, M. D. (2010). No-suicide contracts, no-suicide agreements, and non- suicide assurances: A study of their nature, utilization, perceived effectiveness, and potential to cause harm. The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 31, 290-302. Fowler, J. C. (2012). Suicide risk assessment in clinical practice: Pragmatic guidelines for imperfect assessments. Psychotherapy, 49, 81-90.

Gill, I. J. (2012). An identity theory perspective on how trainee clinical psychologists experience the death of a patient by suicide. Training and Education in Professional Practice, 3, 151-159.

Han, B., McKeon, R., & Gfroerer, J. (2014). Suicidal ideation among community dwelling adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 488-497.

Han, B., Kott, P.S., Hughes, A., McKeon, R., Blanco, C., & Compton, W. N. (2016). Estimating the rates of death by suicide among adults who attempt suicide in the United States. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 125-133.

Hayes, J. A., McAleavey, Castonguay, L. G., & Locke, B. (2016). Psychotherapists’ outcomes with white and racial/ethnic minority clients: First, the good news. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63, 261- 268.

Heilbron, N., Compton, J., Daniel, S. S., & Goldston, D. B. (2010). The problematic label of suicide gesture: Alternatives for clinical research and practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41, 221-227.

Jobes, D. A. (2008). Clinical work with suicidal patients: Emerging ethical issues and professional challenges. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39, 405-409.

Jobes, D. A. (2012). The Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS): An evolving evidence-based clinical approach to suicide risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42, 640- 653.

Joiner, T. E. (2008). Concrete suggestions to improve care for suicidal patients and implications of their limits. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39, 412-413.

Knapp, S., Younggren, J., VandeCreek, L., Harris, E. & Martin, J. (2013). Assessing and managing risk in psychological practice (2nd Ed.). The Trust: Rockville, MD.

Knapp, S., & Gavazzi, J. (2012). Can checklists help reduce treatment failures? The Pennsylvania Psychologist, 8-9.

Linehan, M. M., Korlund, K. E., Harned, M. S., Gallup, R. J., Lungu, A. . . ., Murray-Gregory, A. M. (2015). Dialetical behavior therapy for high suicide risk in individuals with borderline personality disorder: A randomized clinical trial and component analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association, 72, 475-482.

Liotta, M., Mento, C. & Settineri, S. (2015). Seriousness and lethality of attempted suicide A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 21, 97-109.

Luxton, D. D., June, J. D., & Comtois, K. A. (2013). Can postdischarge follow-up contacts prevent suicide and suicidal behavior? Crisis, 34, 32-41. Pompili, M., Lester, D., Forte, A., Seretti, M. E., Erbuto, D., Lamis, D.A., Amore, M., & Girardi, P. (2014). Bisexuality and suicide: A systematic review of the current literature. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11, 1903-1913.

Rudd, M. D. (2006). The assessment and management of suicidality. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press.

Rudd, M. D. (2008). The fluid nature of suicide risk: Implications for clinical practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39, 410-412.

Rudd, M. D Cukrowicz, K. C., & Bryan, C. J. (2008). Core competencies in suicide risk assessment and management: Implications for supervisors. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 2, 219-228.

Rudd, M. D., Mandrusiak, M., & Joiner, T. E. (2006). The case against no-suicide contracts: The commitment to treatment statement as a practice alternative. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 243-251.

Silva, C., Chu, C., Monahan, K.R., & Joiner, T. E. (2015). Suicide risk among sexual minority college students: A mediation moderation model of sex and perceived burdensomeness. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2, 22-33.

Silverman, M. M., Berman, A. L., Sanddal, N. D., O’Carroll, P. W., Joiner, T. E. (2007). Rebuilding the Tower of Babel: A revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behavior Part 2: Suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37, 264-277.

Silverman, M., & Berman, A. L. (2014). Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation Part I: A focus on suicide ideation in assessing suicide risk. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44, 420-431.

Simon, R. I. (2007). Gun safety management with patient at risk for suicide. Suicide and Life- Threatening Behavior, 37, 518.

Stone, D. N., Luo, F., Ouyang, L., Lippy, C., Hertz, M., & Crosby, A. E. (2014). Sexual orientation and suicide ideation, plans, attempts, and medically serious attempts: Evidence from local Youth Risk Behavior Surveys, 2001-2009. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 262-271.

Stroebe, W. (2013). Firearm possession and violent death: A critical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18, 709-721.

Thomas, L. P., Palinkas, L. S., Meier, R. S., Iglewicz, S., Kirkland, T., & Zisook S. (2014). Yearning to be heard: What veterans tell us about suicide risk and effective interventions. Crisis, 35, 161- 167.

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117, 575-600. Wedig, M. W., Frankenberg, F. R., Reich, D. B., Fitzmaurice, G., & Zanarini, M. C. (2013). Predictors of suicide threats in patients with borderline personality disorder over 16 years of prospective follow-up. Psychiatry Research, 208, 252-256.

Weissberg, N. (2011 June). Working with adult suicidal patients. The Pennsylvania Psychologist, 13-14.

Wolford-Clevenger, C., Febres, J., Elmquist, J., Zapr, H., Brasfield, H., & Stuart, G. L. (2015). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among court-referred male perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Psychological Services, 12, 9-15.