SUBSIDIARY RAILROADS OF BETHLEHEM STEEL CORPORATION

Cambria and Indiana Railroad Co. Conemaugh & Black Lick Railroad Co. Patapsco & Back Rivers Railroad Co. Philadelphia, Bethlehem and New England Railroad Co. South Buffalo Railway Co. Steelton & Highspire Railroad Co.

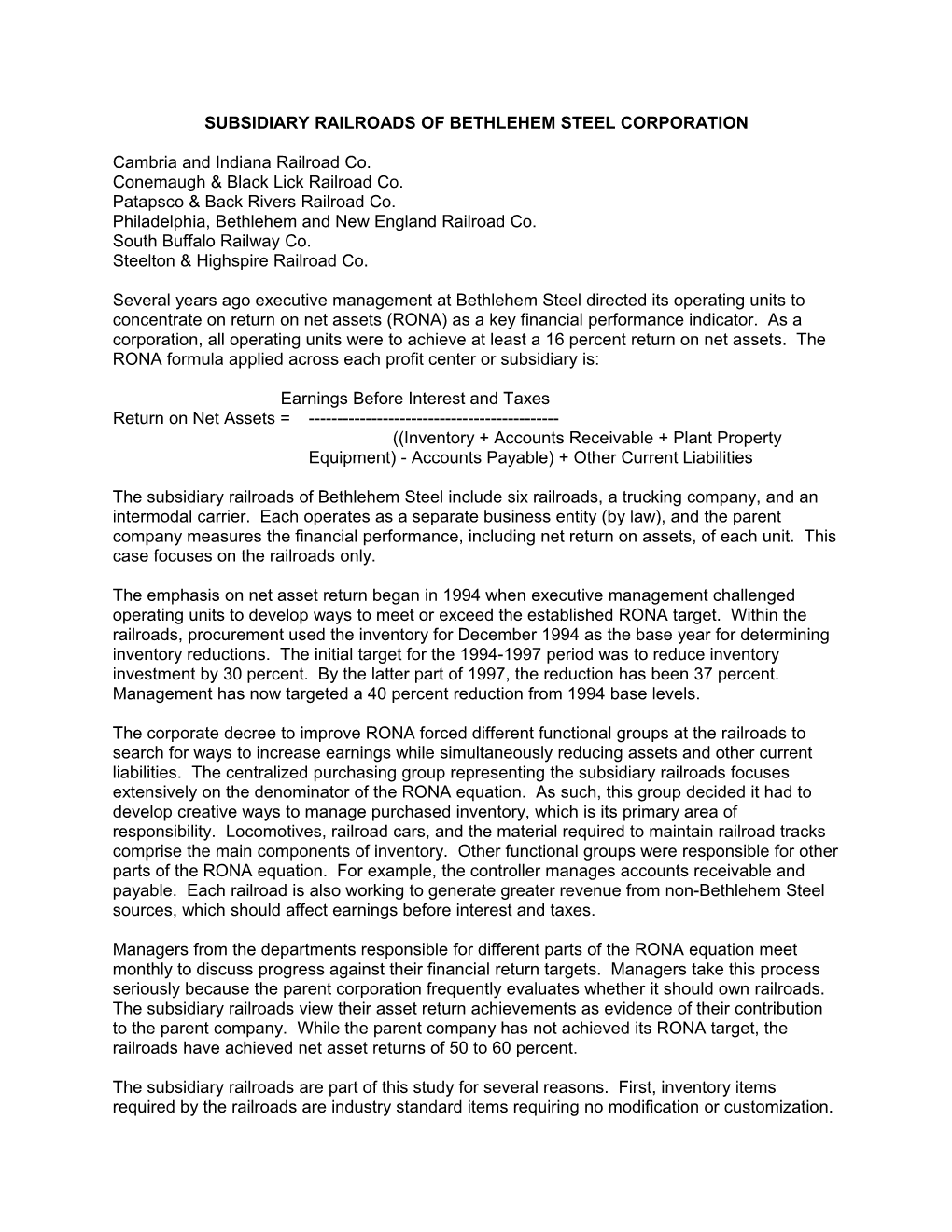

Several years ago executive management at Bethlehem Steel directed its operating units to concentrate on return on net assets (RONA) as a key financial performance indicator. As a corporation, all operating units were to achieve at least a 16 percent return on net assets. The RONA formula applied across each profit center or subsidiary is:

Earnings Before Interest and Taxes Return on Net Assets = ------((Inventory + Accounts Receivable + Plant Property Equipment) - Accounts Payable) + Other Current Liabilities

The subsidiary railroads of Bethlehem Steel include six railroads, a trucking company, and an intermodal carrier. Each operates as a separate business entity (by law), and the parent company measures the financial performance, including net return on assets, of each unit. This case focuses on the railroads only.

The emphasis on net asset return began in 1994 when executive management challenged operating units to develop ways to meet or exceed the established RONA target. Within the railroads, procurement used the inventory for December 1994 as the base year for determining inventory reductions. The initial target for the 1994-1997 period was to reduce inventory investment by 30 percent. By the latter part of 1997, the reduction has been 37 percent. Management has now targeted a 40 percent reduction from 1994 base levels.

The corporate decree to improve RONA forced different functional groups at the railroads to search for ways to increase earnings while simultaneously reducing assets and other current liabilities. The centralized purchasing group representing the subsidiary railroads focuses extensively on the denominator of the RONA equation. As such, this group decided it had to develop creative ways to manage purchased inventory, which is its primary area of responsibility. Locomotives, railroad cars, and the material required to maintain railroad tracks comprise the main components of inventory. Other functional groups were responsible for other parts of the RONA equation. For example, the controller manages accounts receivable and payable. Each railroad is also working to generate greater revenue from non-Bethlehem Steel sources, which should affect earnings before interest and taxes.

Managers from the departments responsible for different parts of the RONA equation meet monthly to discuss progress against their financial return targets. Managers take this process seriously because the parent corporation frequently evaluates whether it should own railroads. The subsidiary railroads view their asset return achievements as evidence of their contribution to the parent company. While the parent company has not achieved its RONA target, the railroads have achieved net asset returns of 50 to 60 percent.

The subsidiary railroads are part of this study for several reasons. First, inventory items required by the railroads are industry standard items requiring no modification or customization. Purchasing standard industry items applies to firms across most industries. Second, the creative use of systems contracts and consignment has potentially wide industry application. The railroads’ approach to systems contracting with consignment and just-in-time delivery of nonstocked items is of primary interest.

Systems Contracting with Consignment Inventory

The purchasing group’s approach to increase RONA involves the development of systems contracts featuring consignment inventory. Inventory consignment involves deferring payment for an item until a user physically takes an item from a railroad yard or warehouse and receives or “posts” the material into the railroad’s inventory. Each year, purchasing works with field managers to identify potential items to add to existing systems contracts, identify items for new contracts, and develop estimates of annual demand requirements for systems contract items at each railroad. Purchasing reserves the right to question the reasonableness of each railroad’s demand estimate. Suppliers deliver all items by truck during the first quarter of each year, and are responsible for unloading and physically placing the inventory in a yard or warehouse. These services are part of the negotiated price. Each railroad has ample space to store inventory.

The five railroads currently have 25 to 30 systems contracts in place with six suppliers. Each contract covers approximately 25 items, with renewal or renegotiation occurring every three years. The contracts are subject to review earlier than three years if suppliers fail to meet expectations. While contract items primarily involve higher value items, the railroads also apply systems contracting to lower unit value items (less than $500) that have higher volume requirements. The railroads view other purchased items as expense items that are not directly part of the inventory calculation.

Although the five railroads operate as separate entities, a centralized purchasing department is responsible for working directly with users at each railroad to develop and negotiate systems contracts. Specifically, purchasing identifies potential items for systems contracts, determines the requirements of each railroad for those items, identifies and analyzes potential systems contract suppliers, coordinates the calculation of annual demand estimates, and represents each railroad during negotiation with suppliers. A key procurement manager, formerly with General Electric, successfully transferred his knowledge of cutting-edge practices, including JIT and inventory consignment, to the railroad as managers discussed ways to improve the denominator of the RONA equation.

Users at each railroad participate during the development of annual purchase requirements. Local managers have the best idea concerning planned maintenance projects and expected usage, so they are responsible for developing local demand forecasts. Furthermore, all sites have an opportunity to present their comments before purchasing enters a new negotiation or renegotiation with a supplier. Before each negotiation internal purchasing customers receive an interoffice correspondence with a sample “boiler plate” systems contract attached. Each railroad has an opportunity to identify the contractual options they prefer, and users can expand the contract by listing any items they would like to see addressed in the final agreement. A supplier will have a contract for each railroad it services.

Determining when inventory is used and issuing payment are vital parts of systems contracting. The railroads assign all purchased items a part number. As a railroad employee removes an item, the local railroad posts the item as an inventory receipt into a computerized inventory control system. The railroads forward usage reports to purchasing, which consolidates the usage into a single report. The report os forwarded to suppliers for billing purposes. Each supplier sends a single invoice for the total usage, not a separate invoice for each railroad. This streamlines the accounts payable and receivable process at the railroads and the suppliers. Suppliers rely on each railroad to provide an accurate reporting of inventory usage for billing purposes.

Exhibit 1 highlights the guidelines followed when evaluating a systems contract for a group or family of items. These guidelines were essential during the initial development of systems contracts. Potential systems contract suppliers receiving a shortened version of this document. At the railroad, these guidelines represent a set of expectations that purchasing wants from these agreements. As it relates to the supplier, these guidelines introduce systems contracting and convey the railroad’s requirements under this approach to contracting.

Exhibit 2 outlines the process followed when formally considering a consignment systems contract for a group or commodity of items. Again, these guidelines and procedures were critical during the early phases of identifying and analyzing potential candidates for systems contracting.

Systems Contracting Benefits

Systems contracting with consignment inventory has resulted in direct benefits for the railroads. First, purchasing is achieving its primary goal of reducing inventory investment. Average inventory has decreased from $2.9 million in December 1994 to $1.8 million in November 1997. The railroads expect further reductions as they expand their use of systems contracts. Cash flow has increased more than $1 million annually due to reduced inventory investment. The railroads have also avoided or deferred price increases due to the fixed three-year systems contract agreements. Systems contracts have also allowed for some downsizing because suppliers assumed responsibilities such as delivering and placing physical inventory in storage. Finally, acquisition costs are lower becuase users submit only an annual order for items covered by systems contracts.

Critical Success Factors

Purchasing has identified certain factors that have been critical to the successful development and management of systems contracts with consignment.

Accurate Demand Estimates Accurate demand estimates are essential for executing and managing systems contracts. Each railroad must accept any unused consigned material into its inventory in January. The railroads agreed to this condition as an incentive for suppliers to participate. Supplies know that inventory cannot be on consignment for more than a year, and at the end of the calender year the railroads pay for any excess consigned inventory. Because the items covered by these contracts are standard to the rail industry and are usually readily available, suppliers must agree to deliver any systems contract item for which the railroad has a shortage within 24 hours.

Because each railroad must assume ownership of unused consignment inventory, the temptation might exist to underestimate annual requirements, particularly with 24-hour guaranteed delivery for items with no on-hand inventory. This would reduce the inventory the railroads have to assume at the end of each year due to overestimating demand requirements. Purchasing has instructed each railroad to provide accurate and reasonable demand estimates for items. Using 24-hour deliveries to cover shortages applies to exceptions rather than normal operations. Purchasing reports that underestimating demand has not been an issue, and suppliers have not voiced any concerns about abusing the 24-hour delivery requirement. Railroads will shift inventory when one railroad has available material and another has a need.

Continuous Communication Purchasing engages in active communication with user groups at each railroad, particularly during the calculation of annual demand estimates for consigned items. Purchasing managers argue that systems contracting has also resulted in improved relationships with suppliers, partly due to the communication required to negotiate, execute, and manage these agreements. Suppliers also receive performance feedback from user groups at least twice a year.

Willingness to Negotiate a Broad Range of Issues Because systems contracts are longer- term agreements, negotiations often involve many non-price issues. Besides identifying which items to include and their prices, a systems contract may address how each railroad wants items delivered or unloaded in its yard, particularly for items that the supplier must deliver on a just-in-time basis. Purchasing’s request to user groups at each railroad is to tell purchasing what they want. All negotiation with suppliers occurs at the headquarters of the corporate parent (Bethlehem Steel), where purchasing leases office space.

Various contractual options include the industry specification the item must meet, pricing requirements, delivery schedule time frames, invoice details and information, payment terms, and inventory management requirements. As a key procurement executive explained, "Anything in these contracts is open to negotiation." Negotiation has taken on increased importance as systems contracts cover most of the railroads’ inventory investment.

Executive Commitment Purchasing conducted frequent, if not daily, meetings with the president of the subsidiary railroads to inform him of the intent and progress of systems contracting. This proved valuable when some suppliers attempted to contact the president directly to challenge the validity of this approach. The railroad president agreed fully with the systems contracting goals and supported the development efforts. This sent a strong message to suppliers concerning the seriousness of systems contracting. Meeting with executive management also served to protect the president from being caught unaware or being influenced when contacted by suppliers.

Determine Pre-consignment Prices Before Pursuing Systems Contracts Early in the process purchasing decreed that it would not accept higher unit charges due to inventory carrying costs assumed or calculated by the supplier. During negotiation planning, purchasing used past costs as a basis for price negotiation, although some suppliers initially attempted to add consignment costs into purchase prices.

Why would suppliers agree to a systems contract that required them to assume additional inventory carrying costs? The railroad has agreed to a three-year fixed systems contract, which typically resulted in greater purchase volumes for each systems contract supplier. Furthermore, agreeing to take ownership of unused consigned material reduced some risk exposure for the suppliers.

Each systems contract supplier receives a guaranteed three-year contract with fixed prices. The only prices that fluctuate are for items that have a high raw material content, such as wood products. The suppliers and the railroad have agreed on a pricing adjustment formula based on published commodity prices.

Planning and Analysis Purchasing relies on spreadsheets to analyze purchased items in detail. Tying into the railroad’s automated inventory databases, purchasing calculates actual usage and company-wide requirements, identifies potential systems contract candidates, and determines inventory investment data. Spreadsheets are also used to analyze supplier- provided data before formal negotiation. For example, a supplier may not be competitive to each railroad for the same items due to transportation cost differences. Separate agreements covering each railroad may be required. Procurement executives argue that computerized spreadsheets using the company’s databases have been invaluable toward the development of systems contracts.

An example shows the importance of prenegotiation planning and analysis. Purchasing sent a request for quotation to several suppliers for items that were to be part of a single systems contract. When the RFQs arrived, a detailed analysis showed that neither supplier was pricing competitively across all items. Purchasing decided to create two systems contracts based on the analysis of early quotations. The results of the analysis highlighted the need for flexibility in the execution phase of negotiation.

Future Enhancements

While the current emphasis is on maintaining existing systems contracts, purchasing plans to negotiate additional contracts in the future. Potential contract areas include brake shoes, locomotive parts, and air brake hoses. Although these items are not as high dollar as those covered by earlier contracts, they can help further reduce the denominator of the RONA equation.

Purchasing is also beginning to renegotiate some three-year agreements. Because systems contracting is a continuing process, renegotiation is an opportunity to strengthen these agreements further. Purchasing is trying to convey to suppliers that only those who accept the basic objectives of a systems contract should continue to the negotiation or renegotiation phase. Several suppliers have yet to take seriously the requirements and goals of systems contracting. Purchasing expects to target these suppliers for elimination or education during the next round of negotiations.

Exhibit 1 Railroad Systems Contract Guidelines

The term Railroad Systems Contract (RSC) defines the type of agreement that the railroad has established or will establish for selected commodities. This type of agreement has been called supplier stocking, systems contracting, annual orders, major blanket order, etc. There is no one recognized definition for this, however, its major goal is a reduction in acquisition costs through lower inventories and better systems. The following describes the features of an RSC: (1) The RSC will require that the supplier maintain the financial and warehousing responsibility for the items covered in the contract. The supplier must consignment stock sufficient quantities to allow the railroad to significantly reduce its inventories. Suppliers will generally guarantee 24 hour or better delivery for item shortages. In other words, the supplier assumes the warehousing function or most of the function formerly handled by the railroad.

(2) The RSC would authorize the Requestor to obtain material directly from the supplier. There would not be any need for requisitions, inquiries, and separate purchase orders. The Purchasing Department would be involved only to the extent necessary to negotiate and audit the agreement.

(3) The RSC would usually be a longer-term relationship than the typical annual order. The agreements would tend to be three-year contracts in that a satisfactory and mutually beneficial long-term relationship is necessary between the railroad and the supplier to obtain the benefits from systems contracting. While the agreements would have a cancellation provision with established controls to assure continuing competitiveness, the costs and penalties for switching suppliers would encourage longer-term agreements. The RSC would promote more of a partnership approach to obtaining best value.

(4) The RSC would be limited only by the scope of each supplier’s active product line, which can be quite broad. Suppliers are expected to have a high level of expertise in the products furnished.

(5) The RSC has as one of its main goals the simplification of the ordering process, which will reduce delivery time and workforce requirements. The use of more automated and simplified means of releasing material is encouraged.

(6) The RSC will promote additional services from the supplier including special EDI order transmittal, reports, consultation, and problem solving services. The extra involvement and expertise will aid in reducing total acquisition costs. Most suppliers involved in this type of agreement will be computerized and able to furnish reports on consumption for the railroad’s evaluation.

On reviewing the features of an RSC, it is clearly the scope of the agreement that differentiates an RSC from the annual order with no precise cutoff point defining when an annual order would become a Railroad Systems Contract.

One final consideration is that the systems contract approach is usually evolutionary and not revolutionary. The original contract will start with a manageable number of items and expand as users gain confidence in the system. A significant amount of time must be spent in the beginning of the project to correctly design the systems or, it will not gain the user acceptance necessary for success.

Exhibit 2 Contract Procedures for Systems Contracts

1. Select a high potential commodity or group of commodities. A high potential commodity generally includes low volume items with a unit value greater than $500, or high volume items with a unit value less than $500. Examples include:

Bearings Electric Industrial supplies Fasteners Lubes Office supplies Paint Pipe and fittings Ties and timber Safety equipment and supplies Track material Tires and tire repairs Truck parts Welding and cutting material

2. Investigate the feasibility of the systems contract approach for the selected commodities. This includes reviewing markets, suppliers, procedures, past practices, future plans, and total dollars involved. Consider the pluses and minuses of the systems contract approach at this point.

A. Develop a list of items to include in a proposed systems contract. The development of the list will require participation from the local railroads. Send a requirements form to each equipment and facilities manager. The list should also include the annual consumption figures and prices if possible.

B. Evaluate the list, including: a. The manufacturers normally used for a particular item and any items for which a substitute may not be possible. b. Establish total usage by item. Identify obsolete or surplus items if possible.

C. Analyze and review the current method of purchase of this group of commodities, i.e., annual orders, individual orders.

D. Analyze the current method of pricing the items, i.e., inquiries, quotes, and bids.

E. Establish any objectives concerning inventory reduction, systems changes, delivery points, and pricing considerations.

3. Prepare a brief written statement of potential benefits and the objectives of the proposed program.

4. Consider the following factors or issues when developing a contract (these may become negotiating topics):

Purpose of agreement Scope of agreement Implementation schedule Term of agreement Product specifications Insurance Definitions:

“A” items: Standard items normally stocked and distributed by the supplier “B” items: Items not normal to supplier’s inventory but stocked at railroad’s request “C” items: Items that are nonstocked, but ordered, manufactured, assembled, or modified by supplier at railroad’s request

Pricing structure of supplier Delivery requirements Repair services Emergency deliveries Invoicing Payment terms Inventory management - Supplier to market excess inventory - Disposition of excess inventory - Consignment stocking - Stocking long lead-time items and published lead times

Credit for tire casings Tire surveys Oil analysis Disposal of scrap Return of surplus Termination Audit and cycle counting Report requirements Other

5. Evaluate potential bidders to determine if they can meet objectives. This may include a letter soliciting written information from perspective bidders and will certainly include a visit to the most likely candidates. The qualification of the bidders is extremely important and the evaluation will narrow the field to those best qualified.

6. Issue an inquiry (invitation to bid) to one or more of the qualified bidders. Critically analyze the inquiry from the railroad and bidder’s viewpoint. The inquiry should list the railroad’s objectives as clearly as possible.

7. Review bids.

8. Negotiate contract.

9. Administer and audit the contract to assure compliance with agreement and competitiveness with market.