#17622

Relational Leadership: New Developments in Theory and Practice

Co-Chairs: Jody Hoffer Gittell, Brandeis University Anne Douglass, University of Massachusetts Boston

Presenters:

Relational leadership as collective leadership: Mapping the territory Erica Foldy & Sonia Ospina, NYU Wagner School of Public Policy

D-Leadership and relational leadership: Beginning the conversation Deborah Ancona, Elaine Backman & Kate Parrot, MIT Sloan School of Management

From relational to sense leadership with savoir-relier: Leading in complexity Valerie Gauthier, HEC Paris

Developing strategic relational leadership Carsten Hornstrup, MacMann Berg; University of Tilburg

Leading in coordination: The meta-feedback role of leaders of performative groups John Paul Stephens, Case Western Reserve

Discussant: Joyce Fletcher, Simmons

Potential Sponsors: Organizational Behavior Organization and Management Theory Organizational Development & Change

1 Relational Leadership: New Developments in Theory and Practice

In this symposium we explore relational leadership and related concepts, highlighting new developments in theory and their implications for practice. Relational leadership is defined here as a pattern of reciprocal interrelating between workers and managers to make sense of the situation, to determine what is to be done and how to do it (Gittell & Douglass, 2012). Each party learns from the other, with workers contributing the more focused in-depth knowledge associated with their roles while managers contribute the broader less focused knowledge associated with their roles. Together they create a more integrated holistic understanding of the situation. This process of reciprocal interrelating involves communicating through relationships of shared goals, shared knowledge and mutual respect, with mutual respect as an emotional connection that heightens each party’s attentiveness to the needs and insights of the other, triggering cognitive connections in the form of shared goals and shared knowledge.

In the traditional bureaucratic organizational form, by contrast, the worker-manager relationship is defined by norms of hierarchy and power-over rather than power-with (Weber,

1920). At the same time this hierarchy is embedded in roles that provide some protection against outright domination (Weber, 1920). “Hierarchy without domination” means that a realm of autonomy exists within the confines of a worker’s job description, protected by formal rules from outright domination (Weber, 1920). Theories of street-level bureaucracy (Lipsky, 1980) as well as more recent theories of job-crafting (Berg, Grant & Johnson, 2010, Wrzesniewski&

Dutton, 2001) suggest that workers do have a realm of autonomy even in traditional bureaucratic organizations, providing them discretion within the confines of their job descriptions and even enabling them to reshape their job descriptions. This realm of autonomy can be used to withhold work effort but can also be used to take actions on behalf of customers or to increase the

2 meaning of the work. Effective use of this autonomy is limited however when workers lack understanding of the whole due to their subordinate position in the bureaucratic hierarchy and their constrained role in the horizontal division of labor.

In the pure relational organizational form, participants exercise influence based on their personal qualities rather than their roles. The upside of the relational form is that participants must earn the commitment or loyalty of other organizational participants. The downside is that the lack of role-based authority means there are no formal limits to the use of that authority, which can degenerate into despotism or nepotism as Weber argued when making his case for the superiority of the bureaucratic form.

Relational leadership differs from the leadership found in the pure bureaucratic form and the pure relational form by being both role-based and reciprocal. Relational leadership builds on

Follett’s (1949) concept of reciprocal control, a form of control that is not coercive but rather “a coordinating of all functions, that is, a collective self-control” (1949: 226). Achieving this collective self-control, she argued, requires a form of leadership that is distributed throughout the organization rather than concentrated in a few positions. Follett observed organizations in which

“we find responsibility for management shot all through a business [and] some degree of authority all along the line [such that] leadership can be exercised by many people besides the top executive” (1949: 183). Rather than vesting authority in one person over another based on his or her position in the hierarchy, authority is shared (Fletcher, 1999). The core characteristic of relational leadership is the embedding of authority into each role, based on the knowledge associated with it.

Distributed leadership, carried out by both formal and informal leaders throughout the organization to facilitate achievement of organizational objectives (Ancona & Bresman, 2007),

3 has several characteristics in common with to relational leadership. Distributed leadership is a form of influence that can be exercised by participants at any level of an organization, and moreover, leaders are most effective when they can inspire others to engage in the responsibilities of leadership rather than attempting to carry out all leadership responsibilities on their own. Distributed leadership thus would appear to require facilitative leadership behaviors rather than directive leadership behaviors, and transformative leadership behaviors rather than transactional or passive leadership behaviors. Lending support to this perspective, Carson and co-authors (2007) found that supportive supervisory behaviors predict greater frontline worker engagement in shared leadership.

However, relational leadership does more than draw upon expertise and leadership from participants throughout the organization. It is a process of reciprocal interrelating through which the expertise held by different participants interpenetrates, creating a more holistic perspective that is integrative rather than additive. Relational leadership requires facilitating the interpenetration of expertise among others, which in turn requires the skills to build relationships among others, creating a safe space in which they can reciprocally interrelate with each other.

According to Lipman-Blumen (1992: 184), facilitating connections among others is a key attribute of connective leadership:

Connective leadership derives its label from its character of connecting individuals not

only to their own tasks and ego drives, but also to those of the group and community that

depend upon the accomplishment of mutual goals. It is leadership that connects

individual to others and to others’ goals, using a broad spectrum of behavioral strategies.

It is leadership that ‘proceeds from a premise of connection’ (Gilligan, 1982) and a

4 recognition of networks of relationships that bind society in a web of mutual

responsibilities.

Fletcher’s concept of ”fluid expertise” (1999: 64) in the worker-manager relationship reflects a co-creation process consistent with relational leadership:

[P]ower and/or expertise shifts from one party to the other, not only over time but in the

course of one interaction. This requires two skills. One is a skill in empowering others;

an ability to share - in some instances even customizing - one's own reality, skill,

knowledge, etc. in ways that made it accessible to others. The other is skill in being

empowered: an ability and willingness to step away from the expert role in order to learn

from or be influenced by the other.

Fluid expertise requires mutual respect, as well as the ability to be caring, responsive and closely attuned to another through the development of both cognitive and emotional connections. One characteristic of relational leadership is leading through humble inquiry, described by Schein

(2009) as a form of giving, seeking and receiving help that leaders can use to establish a culture of reciprocal learning throughout an organization.

Relational leadership (worker-manager), along with relational coordination (worker- worker) and relational coproduction (worker-customer), are three processes of reciprocal interrelating that form the core of relational bureaucracy. Relational bureaucracy is a hybrid of the relational and bureaucratic forms in which reciprocal interrelating enables participants torespond to each other in knowledgeable and caring ways, while formal structures embed reciprocal interrelating into roles, thus enabling the scalability and sustainability typically associated with the bureaucratic form (Gittell & Douglass, 2012).

Structure of symposium

5 This symposium explores relational forms of leadership, with participants from multiple perspectives seeking to articulate the theories behind these forms of leadership as well as their implications for practice. We start with a mapping of the territory by Foldy and Ospina, arguing that relational leadership is one of several forms of collective leadership. Ancona, Backman and

Parrott follow with an updated look at distributed leadership and its characteristics – distributed, decentralized and decoupled from roles, outlining similarities with and differences from the concept of relational leadership.

Gauthier and Hornstrup each explore relational leadership as a process of sensemaking in the face of complexity, recognizing both cognitive and emotional dimensions of this process.

We conclude with a study by Stephens that explores how leaders foster coordination among others through meaning making, a process that involves embodying the whole for diverse participants.

As discussant, Fletcher will launch the symposium with buzz groups, asking audience members to discuss with each other what they hope to learn. She will break at two points during the symposium to allow additional buzz groups among audience members, then will present her overarching commentary at the conclusion, followed by audience discussion.

6 Potential sponsors

The proposed symposium explores the micro-processes of relational leadership, thus creating a potential fit with the Organizational Behavior Division. We explore the implications of these micro-processes of leadership for the organizational form itself, and the organization’s ability to achieve critical performance outcomes, thus creating a potential fit with the

Organization and Management Theory Division. We explore relational leadership as a means for transforming mechanistic organizations to become more responsive to complexity and uncertainty, creating a potential fit with the Organizational Development and Change Division.

7 Relational leadership as collective leadership: Mapping the territory

Erica Gabrielle Foldy & Sonia Ospina Wagner School of Public Service, New York University

As criticisms of traditional leadership theory and research amplify and diversify, a variety of new terms challenge the notion of leadership as a one-directional relationship between leader and follower. Scholars have referred to leadership as “shared”, “distributed,” “constructed,”

“post-heroic” and “relational” among other terms (Pearce & Conger, 2003; Gronn, 2002;

Hosking, 2003; Drath, 2001; Ospina & Sorenson, 2006; Fletcher, 2004; Uhl-Bien, 2006). While they all rest on a basic assumption that leadership does not automatically reside in a single, often heroic, individual, these conceptualizations of shared leadership vary widely. In this presentation, we provide a brief map of the territory -- a framework that suggests the basic dimensions that can differentiate these approaches. We then suggest “collective leadership” as an umbrella term that encompasses these conceptualizations and position relational leadership within this framework.

The move away from the single, heroic, leader is not new. Several decades of scholarship have explored how leadership is practiced – implicitly or explicitly -- as a joint endeavor (Hollander, 1964; Burns, 1976; Rust, 1991). However, the last decade has seen a burst of scholarship investigating this phenomenon, along with a proliferation of terminology to describe it. While many of the terms may appear similar or even interchangeable, in fact they differ significantly in what they describe. Having reviewed the relevant literature in management and organization studies, psychology and education, we suggest two basic dimensions along which the different approaches can be plotted: the “locus of leadership” and the “view of self”

(see Table 1).

8 The locus of leadership is where leadership resides; it is the source of leadership or its

“epicenter” (Hiller, Day and Vance, 2006); it is where, as researchers, we look for leadership.

There are three loci: the individual, the relationship and the system. The traditional and still dominant perspective is the individual as the locus of leadership: leadership is enacted by individuals who have the appropriate traits, characteristics or styles and engage in measurable leaderly behaviors (Antonakis et al, 2003). Other work understands leadership as based in the relationship between leaders and followers: “Leadership is a concept of relationship; it assumes the existence of some people who follow one or more others… There can be no leadership if there is just one person” (Pearce, Conger and Locke, 2007, 287). A third approach is to see leadership as belonging to the collective (Drath et al, 2008) or residing in a system or context – social, organizational, even a group or team. Spillane et al, scholars of education, suggest leadership should be conceptualized as “a distributed practice, stretched over the social and situational contexts of the school” (their italics; 2004; 5). Smircich and Morgan see leadership as

“enact[ing] a system of shared meaning that provides the basis for organizational action” (1982:

258).

Views of self are rooted in the researcher’s ontological and epistemological assumptions about the very nature of human beings, with consequent understandings of “the self” as individuated and autonomous or connected and co-constructed. When applied to leadership, these assumptions paint different pictures of how the relationships undergirding leadership actually work. Positivist and post-positivist approaches understand the self as a distinct entity, clearly bounded, which then engages with other, similarly autonomous beings (Uhl-Bien, 2006;

Ospina&Uhl-Bien, forthcoming). In this “entity” approach, the leader and leadership are confounded (Hosking, 1988), with leadership defined as an influence relationship between two

9 social actors -- leader and follower -- who exist as such, prior to the relationship. Leadership is explained by the neo-charismatic school, for example, as a process by which leaders “affect followers as a result of motivational mechanisms that are induced by the leaders’ behaviors”

(Antonakis, 2011: 270), including “visionary behavior, positive self-presentation, empowering behaviors, calculated risk taking and self-sacrificial behavior, intellectual stimulation, supportive leader behavior and adaptive behavior” (271).

In contrast, a constructionist perspective sees the self as self-in-connection, created through interaction, with no inherent core or status independent of that which is forged through that interrelationship (Dachler& Hosking, 1995; Ospina &Uhl-Bien, forthcoming). In the constructionist approach, leadership (and those defined as leaders or followers) emerges in process as co-constructions that help advance organizing tasks (Hosking, 1988). Leadership happens in context, it does not exist prior to the relationship: "leaders must constantly enact their relationship with their followers;" they "must repeatedly perform leadership in communication and through discourse" (Fairhurst, 2007: 5). In this approach leadership is understood as relational in that it emerges only in the context of “a particular form of interaction happening at a certain time and place” (Drath, 2001: 16). In this sense, leadership is not something that the leader, as one person, possesses, as much as it is something achieved in community and owned by the group (Ospina& Sorenson, 2006; Foldy et al, 2008).

Plotting each of the two dimensions on a separate axis creates six cells which each represent a different conceptualization of collective leadership, corresponding to different degrees or types of collectivity. (In Table 1, we have suggested specific approaches and scholars whose work illustrates each cell.) We very deliberately choose the term “collective” because it can encompass all of the quite varied forms in the framework. Terms like “distributed” or

10 “joint” leadership suggest that leadership resides in autonomous individuals who then share particular leadership tasks. Words like “processual” (Hosking, 1988) or “discursive” (Fairhurst,

2007) imply a more disembodied approach, one that investigates the process or work of leadership rather than the behaviors of individual leaders and followers. The term collective is elastic enough to provide a broad umbrella, as suggested by this definition: “involving all members of a group as distinct from its individuals”1.

The place of relational leadership in the framework varies because people have used the term in different ways. For example, the definition posed for this panel is relational leadership as

“a process of role-based reciprocal interrelating” between workers and managers to negotiate the work that is to be done. In contrast, Uhl-Bien (2006) defines relational leadership as “a social influence process through which emergent coordination (i.e., evolving social order) and change

(e.g., new values, attitudes, approaches, behaviors, and ideologies) are constructed and produced.” (2006: 655) The first definition implies that leadership inheres in independent individuals who inter-relate across different hierarchical positions. The second locates leadership in a jointly constructed but disembodied process, not in individuals. Uhl-Bien (2006) proposes Relational Leadership Theory as an approach that can encompass both individuated and connected perspectives by explaining both the emergence of leadership relationships (drawing on traditional individuated views that focus on the nature of the relationship, such as Leader-

Member Exchange), and the relational dynamics of organizing (including various constructionist views of leadership). In fact, the term “relational” has been used to refer to quite distinct understandings of leadership, each with different ontological and epistemological assumptions

1 Retrieved from On-line Merriam-Webster Dictionary, December 30, 2011: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/collective

11 that result in quite distinct approaches to conducting research (Uhl-Bien &Ospina, forthcoming).

This suggests the timing is right for a symposium exploring relational leadership.

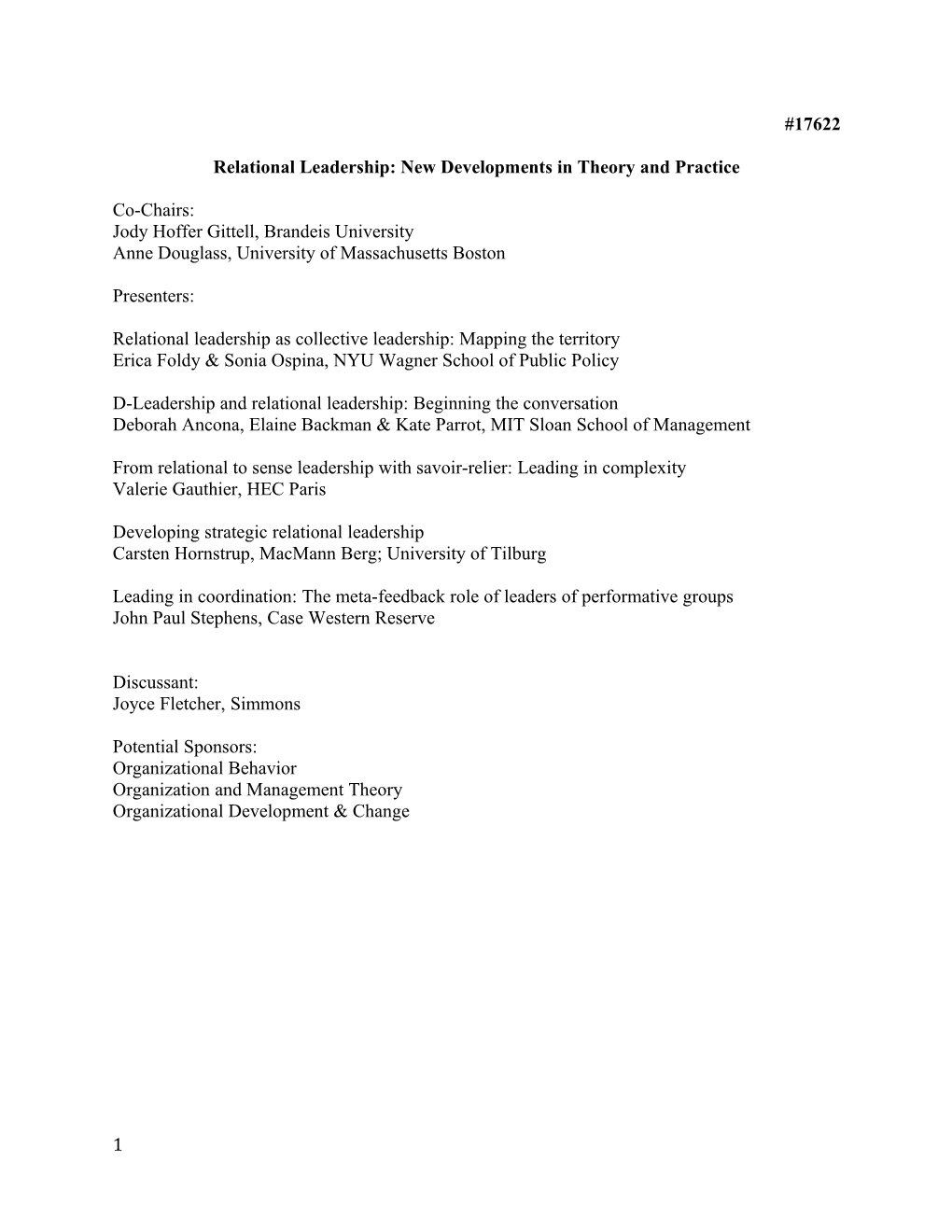

Table 1: A map of collective approaches to leadership

View of Individuated self Connected self “Self”

Locus of leadership Individual Co-leadership – Sally Connective leadership – (2002); Hennan & Bennis Lipman-Blumen (1992) (1999) Leadership couples – Bennis & Biederman (1997); Gronn (1999) LMX – Graen & Scandura, Relational Leadership Relationship (1987); Graen & Uhl-Bien Theory - Uhl-Bien (2006) (1995) Post-heroic Leadership – Relational Leadership – Fletcher (2004) Gittell & Douglas (2012) Follower Centered Leadership – Meindl (1995); Shamir et al (2007) Shared Leadership – Pearce & Conger (2003) Distributed Leadership – Constructed Leadership - System Gronn (2002); Spillane Drath (2001); Ospina & (2006) Sorenson (2006); Foldy et Shared Leadership in al (2008) teams- Carson, Tesluk & Discursive Leadership Marrone (2007); Day, -Fairhurst (2007) Gronn & Salas (2006) Processual Leadership Networks – DeLima (2008); -Hosking (1988) Balkundi & Kilduff (2006) Complexity Leadership Theory - Uhl-Bien, Marion &McKelvey (2007)

12 D-leadership and relational leadership: Beginning the conversation

Deborah Ancona, Elaine Backman & Kate Parrot MIT Sloan School of Management

The purpose of this symposium is to explore relational leadership and related concepts. In this presentation, we introduce the concept of “D-leadership” which we developed based upon intensive fieldwork in organizations operating in dynamic, highly competitive industries. D- leadership refers to leadership that is decentralized, distributed and collective, and de-coupled from organizational roles. In the presentation, we provide a brief description of our research questions and methods; present the D-leadership model; highlight our main findings; and identify three ways that the D-leadership model differs from the relational leadership model developed by the symposium organizers.

Research background

There are two largely separate but parallel literatures documenting the fact that both organizations and leadership practices have changed dramatically over the past three decades. On the one hand, macro-organizational scholars have provided evidence that organizations have become flatter; more reliant on the use of teams; less formalized with fewer work rules and less detailed job descriptions; and characterized by more porous boundaries (DiMaggio 2003). On the other hand, micro-organizational scholars have found that in many sectors, there has been a move away from “command and control” leadership in which leadership is exercised individually by those in formal positions of authority in a clearly defined hierarchy, toward

“shared leadership” (e.g. Carson et al, 2002), “distributed leadership” (e.g. Gronn 2002) or

“complexity leadership” (e.g. Uhl-Bien et al 2007) in which leadership is exercised by multiple leaders throughout the organization -- some in formal positions of authority and some not

13 --working collaboratively across organizational levels and boundaries. This research brings these two literatures together by: 1) providing detailed, empirical descriptions of how collaborative leadership is being practiced in organizations considered exemplars in this new leadership form, and 2) identifying what organizational structures, practices and cultures support it. We employed a theory-building, comparative case study methodology (Eisenhart & Graebner

2007) using the following data sources:

A study of leadership practices at two R&D labs at a Fortune-500 business equipment and

services company, one with a long history of collaborative leadership practices, the other

which operated in a “command and control” manner. We studied two product development

projects in each lab relying on extensive interview data augmented by archival data,

observation of on-site meetings, and feedback sessions with study participants.

A study of leadership practices in a mid-sized, privately held company that develops and

manufactures high-tech products in consumer and business markets considered an exemplar

of collaborative leadership. We studied two product development teams, two process

change efforts, and two strategic change initiatives, relying on extensive interview data

augmented by archival data, observational data from site visits in the U.S, China and

Germany, and feedback sessions with study participants.

Secondary data from five other companies known as exemplars of collaborative leadership

to fill in gaps and add external validity to our case study findings.

Findings

1. “D-Leadership”

In analyzing leadership patterns in organizations identified as exemplars of collaborative leadership we found that they are characterized by three inter-related factors:

14 Leadership is more decentralized than in command and control organizations, with

many change initiatives initiated and led by individuals and teams operating at lower

organizational levels.

Leadership is designed to tap the distributed and collective intelligence of

organizational members in making leadership decisions. Thus, leadership is often

shared among individuals with different forms of knowledge and expertise.

Leadership is more decoupled from formal leadership positions than in traditional

command and control organizations. Many individuals in non-managerial positions

initiate, champion and lead change initiatives.

In short, we found that leadership in these settings was decentralized, distributed and collective, and decoupled from formal roles, hence we call our model “D-leadership”

We were also struck by three additional findings. First, we found very high levels of leadership self-efficacy at all organizational levels. Many individuals drive change within these organizations and have confidence in their ability to step into leadership roles. Second, we found employees in these settings shared a broad awareness of the business goals and strategies of their organizations, a phenomenon we call a “global mindset.” This meant that, regardless of their formal roles, individuals could exert leadership informed by the broader goals and guiding principles of their organizations. Third, we found these organizations had routines for vetting ideas, creating teams, conducting experiments and accessing organizational resources in a timely manner that were widely-known and accessible to members throughout the organization. In short, there were interwoven sets of dynamic capabilities that facilitated leadership within innovation and change processes.

15 2. Organizational practices and policies that support D-leadership

The following organizational structures, practices and cultures appeared to support D-leadership:

Hiring for leadership self-efficacy and collaborative ability

Long on-boarding processes and ongoing socialization to sustain strong understanding of

organizational goals and principles as an aid to decision-making

Organizational managers operating as coaches, not bosses

Orchestration of, and rewards for, creative, cross-functional interaction and collaboration

Well developed processes for collective vetting and selection of new initiatives

Just-in-time structures and flexible resources available for new initiatives

Mechanisms for coordinating and aligning individual and team efforts

Widely shared mechanisms and norms that support risk prevention and mitigation

A culture of perceived fairness and transparency

Relational leadership and D-leadership

In their conceptualization, Gittell and Douglass define relational leadership as “a pattern of reciprocal interrelating between workers and managers regarding what is to be done and how best to do it” (Gittell & Douglass 2012). This form of leadership, they argue, allows organizations to fuse the more focused, in-depth knowledge of workers with the broader, less focused knowledge of managers to create a “more integrated, holistic understanding of the situation” (Gittell& Douglass 2012). Finally, they note that relational leadership is one of three key processes in role-based interrelating, along with relational coordination (worker-worker) and relational coproduction (worker-customer). The D-leadership model differs in a number of important ways:

16 1. In the D-leadership model, leadership decisions arise not just from worker-manager

interactions, but from worker-worker and worker-customer interactions as well. In fact,

our case data suggests that these decisions most often involve intertwined sets of

recursive interactions involving all three types of agents. Thus the level of analysis shifts

from the dyad to the system or network of relationships.

2. The relational model rests upon the assumption that managers and workers have very

different knowledge bases. In the organizations we studied, however, there was a great

deal of overlap in the knowledge base of workers and managers.

3. Finally, in the D-leadership model, leadership behavior emerges from the interaction of

leaders, teams and contexts. Leadership cannot be viewed in isolation but must be seen

as an emergent process.

17 From relational to sense leadership with savoir-relier: Leading in complexity

Valérie Gauthier HEC Paris, MIT Sloan

In the concept of savoir-relier, we address two dimensions of leadership: relational and sensible. We define savoir-relier as the capacity and will to build sensible, trustworthy and sustainable relationships across boundaries (i.e. between entities that are inherently different, opposite or antagonistic), hence encouraging and valuing differences to engage in positive and mindful innovation. To do so, savoir-relier enacts sense (meaning, sensibility, vision) out of complexity for both the individual and the organization in their relation to the world as they become relational sense-builders who are capable of embracing complexity with efficiency as well as respect and humility.

This article is based on three assumptions: 1) Following Morin’s theory on complexity

(from the Latin Complexus: “that which is woven together”), we argue that the world’s complexity cannot be filtered through the lens of rationality or specialized and isolated scientific disciplines alone; thus organizational theory needs to bind psychological and sociological perspectives and open to subjective sensibility as a complement to objective rationality and to transdisciplinarity as a new way to address this complexity. 2) Secondly we argue that the savoir- relier process for leaders and organizations is analogous to the process of poetic translation as presented in the poetic translation theory (Gauthier, 1994): by translating the unexpected associations between heterogeneous constituents (as in the sounds, images and meaning in a poem) and by re-creating a new and dynamic ensemble that builds mindful and sensible sense for the new environment in which it thrives. 3) This understanding of complexity and poetic metaphor applied to leadership opens the door to a new way of approaching leadership where the relational sense-building capacity of individuals and organizations as living systems functions

18 effectively in complex settings that carry a multiplicity of paradoxical constituents and uncertainty factors. We will address the role of the SR leader, manager or function in the organization with reference to three different settings. In so doing, we will thus link to existing research and lay foundation for future research in organizational theory, leadership, decision- making or any other area touching upon complex thinking where the savoir-relier perspective can be further exemplified and strengthened.

Savoir-relier as a response to complexity

We understand complexity as posing the paradox of the one and the many, of order and disorder, of subject and object, of reductionism and holism. Facing complexity in this way requires a paradigm shift where relationship and sense building play a central role. At the level of organizations, large and small, anywhere in the world, we argue that the need for sense to perform at complex global levels involves savoir-relier capacity. It is translated into organizations that face and address complexity as “a fabric of heterogeneous constituents that are inseparably associated” (Morin, 2008) by developing a savoir-relier that builds sense out of mindful connections between those constituents and fosters positive innovation. Complexity is

“the fabric of events, actions, interactions, retroactions, determinations, and chance that constitute our phenomenal world” (Morin, 2008).

Organizations as living systems

The complexity theory of Morin draws from a wide range of domains where savoir-relier already applies, such as natural sciences and human sciences and we open the door to different possible applications and research to further demonstrate the relevance of this concept for thriving businesses and people in our 21st century world of complexity. For instance, the science of ecology was born out of the central concept of ecosystem: “the organizational ensemble that

19 constitutes itself by means of interactions between living beings and the geophysical conditions of a specific place… ecosystems are themselves part of the biosphere which has its own life and regulations” (Morin 2008: 88).

To further explain what subtends Morin’s vision of complexity we illustrate the three principles it relies on: dialogic, recursive and holographic. The dialogic principle emphasizes a special kind of link where the elements are necessary to each other, both complementary and antagonistic. The second principle is called recursive as individuals produce society that produces individuals. This cycle of production is itself self-constitutive, self-organizing and self- producing, hence producing a relational circuit. The third principle surpasses both reductionism and holism by relying on the image of the hologram where the sociologist is part of the society of which she is not the center, but a part and possessed by all society. In the end, the holographic principle binds with recursive logic, which is linked to the dialogic idea so that knowledge of the parts is enriched by knowledge of the whole, which in turns draws from knowledge of the parts, producing a single productive movement of knowledge.

Relational leadership as a sensemaking process

While building upon Morin’s theory of complexity we make a positive link with the use of the basic evolutionary epistemology process assumed by the organization concept of sensemaking (Weick, 1993). In this sensemaking process, we see a transition between the complex thinking process and the savoir-relier process through the retrospective interpretations that are built during interdependent interaction (Campbell, 1965, 1997). Sensemaking can be treated as “reciprocal exchanges between actors (Enactment) and their environments (Ecological

Change) that are made meaningful (Selection) and preserved (Retention). We will call this model

“enactment theory,” as has become the convention in organizational work” (e.g., Jennings and

20 Greenwood 2003in Weick, 2005: 414). While this retrospective process differs from the recursive principle in Morin’s theory, the reciprocal interrelations and the notions of ambivalence in the use of previous knowledge can be linked to the complex and dynamic holographic and dialogic principles.

Accordingly, using an analogy with the poetic translation process (Gauthier, 1994) we argue that the following skills are necessary for effective relational leadership: 1) An intuitive mind to perceive the unique and complex forces that build sense out of a system. It is the same intuition that, pushed by the desire to innovate and combined with creativity, will help in the final act of re-creation and sense-building in line with decisions made on the way. 2) An analytical mind to get a deep understanding by decomposing and decoding complex situations and problems. This refers to the capacity of a leader to discern patterns, understand different viewpoints, listen and empathize with people’s diverging and heterogeneous ideas before and in order to forge a vision and before making any decision. 3) The ability to integrate uncertainty and chance in assimilating the complexity of the environment where the situation lies and where it goes (vision) thanks to the holographic principle. The leader here needs to capture the sum of contradictory and ambiguous pieces of information both as part and as a whole to build a vision for the organization to move forward. To be effective, such assimilation of uncertain chance events requires a high degree of self-awareness and introspection in order to identify and accept the role of the subjective in the objective so as to build a sound and responsible vision for the organization. 4) A capacity to “decenter” oneself and create a movement from the original situation in its living system to the new one, which encompasses agility. Here the leader proves again her capacity to adapt but also to weave between antagonistic environments or living systems embedded in their language, space, culture and time. In leadership, this can be

21 exemplified by strategic thinking (versus programming or planning). 5) Finally, the courage, creativity and drive to make choices, decisions, and take calculated risks in the act of creative translation so as to communicate them effectively. This final act of re-enunciation or re-creation is what really distinguishes the savoir-relier leader from others by integrating timely, mindful change and innovation with a sense of humility.

Applying savoir-relier to examples from recent research

We will finally explore how the savoir-relier concept can apply to organizations, using three examples from recent research: 1) case managers in hospitals working across functional boundaries as shown by Kellogg, 2) HR systems and helping in organizations as shown by

Mussholder et al and 3) brokers’ role in building creativity and innovation in the music industry as shown by Long Lingo and O’Mahoney. These three examples will be presentedto demonstrate how savoir-relier contributes to further understanding relational leadership as a process of sensemaking.

Conclusion

To survive the 21st century’s rational, specialized, individualistic and complex world, organizations need to resolve the tension between the necessary agility to adapt to a fast changing complex environment and the need for sense reflected in their ability to foster innovation with vision, sensibility, mindfulness and ethical values. Whether this tension is positive or negative, the resulting challenges and paradoxes require a new approach to leadership, which involves two essential building capacities: one with respect to relationships and the other with respect to sense.

22 Developing strategic relational leadership

Carsten Hornstrup MacMann Berg/University of Tilburg

The aim of this research project is to develop a relational approach to strategic leadership and organizational communication. In the initial face of the project the focus has been to develop a coherent theoretical framework, inspired by systemic and constructionist ideas. The ambition is to use his frame as a thinking tool (Hornstrup et.al. 2012) as a source of inspiration for developing fruitful practices. The basic idea is that modern organizations are facing two key challenges. Building on interviews with 1500 CEO’s from public and private organizations, the conclusion is, that the increasing complexity and an increasing change rate is by far seen as the two biggest challenges for managers. To be able to exist and thrive in these circumstances, organizations must be able to exploit complexity and change. One of the key elements in doing so is by developing their ability to change or innovate their management and organizational processes. In other words, the challenge is to get from change management to creating organizations that develop their adaptability or changeability.

Background

Increasing complexity and speed of change are two of the key challenges we face in strategic leadership of modern organizations (Hamel 2007, IBM 2010). One of the key obstacles to meeting these challenges is the use of out-dated mental models, built on a rational and mechanical understanding of organizations and human communication (Pearce 2008, Gergen

2010). These mental models have much more in common with the early 20thcentury thinking with its focus on solving very simple problems – creating frameworks for turning human beings into “semi programmable robots” (Hamel 2007). As Hamel argued: ”To a large extent, your

23 company is being managed right now by a small coterie of long-departed theorists and practitioners who invented rules and conventions of ‘modern’ management back in the early days of the 20thcentury. They are the poltergeists who inhabit the musty machinery of management” (Hamel 2007: ix). When considering the images often used to describe organizations, the mechanistic view can be seen in the charts and diagrams that tend to dominate our thinking about organizational design. “They are the product of the static understandings generated by a mechanical view of organizations” (Morgan 1997: 6).

An important difference between a mechanistic and a systemic-constructionist approach to organizational communication is that the former is based on an epistemology that assumes we can transmit information, knowledge, experiences from one person or one consciousness to another (Weick 1995, Pearce 2004, 2008), while the latter is based on the notion that each group constructs its own image of the world (Maturana & Varela 1987, Maturana &Poerksen 2004).

This socially constructed image guides people’s perception of themselves and the world around them and guides the way they communicate and create relationships within and outside their group (Gergen 2009, 2010).

Strategic relational leadership

In developing the concept of strategic relational leadership, I address three different domains of leadership communication (Lang, Little & Cronen 1990, Hornstrup et. al. 2012).

Together these domains can open us to seeing organizations as not just as “systematic (rational) systems” but also as “ecologies of relationships and communication” (Bateson 1972, 1979).

These domains include both the domain of production, the domain of aesthetics and the domain of explanation. The domain of production focuses on how the more rational aspects of relationships and communication influence organizational coordination through clarity and

24 transparency while the domain of aesthetics focuses on how the more emotional side of relationships and communication influence organizational coherence and coordination through culture, emotions, beliefs and attitudes. Finally the domain of explanation includes curiosity, reflexivity and irreverence (Cecchin 1987, Tomm 1988, Cecchin et.al. 1992, Barge 2004,

Hornstrup, Tomm & Johansen 2009).

Looking at the different domains in a more practical light, each contributes to our understanding and ability to work with strategic organizational issues. The domain of production invites us to develop organizational patterns of stable relationships and communication in a way that creates clarity and transparency – clarity about goals, roles, directions and relations and transparency about what, why and why not. Transparency is a way of addressing the things we can be relatively certain about while admitting that there are unforeseen or unknown issues that will influence us as we move into the future. In this way transparency is a vital part of creating more distributed strategic competences because it invites everyone to be aware of uncertainty and thereby invites everyone to pay attention to the fact that things very well might change

(Pearce 2008).

The domain of aesthetics, with its focus on culture, emotions, beliefs and attitudes, is important both as a condition for and an obstacle to change. Very often organizational cultures and values work as a hindrance for change. Using the iceberg metaphor, the largest and heaviest part of organizational culture is below the water line and pulls in the direction of stability. We must be aware of the effects of cultures and values and look at them with both appreciative and irreverent eyes (Cooperrider & Srivastva 1987, Cooperrider & Withney 1999, 2000). To look at them with appreciative eyes means to look at them as an underlying logic that guides the way we see, understand and act (Hornstrup & Loehr-Petersen 2003). If we don't appreciate the value and

25 the culture, very often people will take it as criticism of something dear to them. In other words, before moving in the direction of changing the organizational system, we should be aware of the positive aspects of any culture. At the same time we need to look at cultures with irreverent and challenging eyes – or rather, invite people to be active participants in taking an irreverent look at their own culture. If we don't involve people in this process, and do it with a high degree of transparency, we often end up with even more change resistant organizations (Steensen 2010).

To keep the awareness and ability for change, the domain of explanation is vital. It is by keeping a reflexive open mind and keeping our curiosity alive that we create organizations with a high degree of flexibility. If we connect these capabilities (curiosity, reflexivity and irreverence) to the domains of production and aesthetics, we can open up space for more flexible structures and procedures and create cultures where change is a natural part of organizational life.

Together, I propose, these three domains allow leaders to bridge the hard-core and soft-core aspects of leading and organizing.

26 Leading in coordination: The meta-feedback role of leaders of performative groups

John Paul Stephens Case Western Reserve University

Recent research on coordination has had little to say about the role of leaders. Rather, organizational scholars have focused more on the practice of coordination amongst organizational actors. Specifically, scholars have focused on how various qualities of communication and feedback influence coordination, such as speech, actions, and systems that reflect more mindful consideration of the relationships amongst actions within and between workgroups (Bechky, 2003; 2006; Dougherty, 1992; Gittell, 2002; Hargadon & Bechky, 2006;

Kellogg, Orlikowski, &Yates, 2006; Weick & Roberts, 1993). All of these studies have provided detailed knowledge of how individuals use symbols, language, and routines to successfully interrelate their actions at work. However, we know little about the involvement of those in leadership positions (as managers or centralized coordinators) who must surely be present in these contexts.

The place of leaders in coordination at once seems important, but may understandably have been left as secondary to organizational scholars. Leadership is important because coordination has been defined as the "management of interdependencies" (Malone &Crowston,

2000), and calls for the examination of coordination at the managerial level of analysis were made over thirty years ago (see Van de Ven, Delbecq, & Koenig, 1976). On the other hand, the role of supervisors, managers and leaders may be readily downplayed in coordination research given the decreasing importance of hierarchy in modern work organizations that rely more on virtual collaboration and networked designs. However, even the more recent accounts of coordination that examine post-bureaucratic, less-hierarchical organizational contexts, hint at the

27 role of those in senior management positions concerned with "different groups of people with different skills, backgrounds, and experience, education, career expectations, expectations about what their work day will be like" (Kellogg, Orlikowski, & Yates, 2006: 26). In a similar context, the CEO of a modern design firm was aware of how important it was to "pick two people, with different experiences and maybe even different training and put them together and you’ve got that kind of a synergy, an exchange of ideas" (Hargadon & Bechky, 2006: 489). Thus, the fluid self-organization of organizational actors that took place in these contexts was at least partly overseen and understood by someone in a managerial or leadership role. Accounting for the mutually-reciprocal influence between those who must lead groups of people interrelating their actions, and those performing coordination should enhance and make more robust our explanations of how coordination works and why it might sometimes fail.

Some exploratory theoretical and empirical work begins to describe how leaders may be involved in the coordination of workgroups. First, while Weick and Roberts' (1993) description of how coordination occurs through heedful interrelating focuses primarily on how individual crew members relate their efforts, they also describe how the bosun, or the ship's central coordinator envisages the work of the collective. They describe how the bosun thinks "about the kind of environment he will create on the deck that day, given the schedule of operations...he represents the capabilities and weaknesses of imagine crewmembers' responses in his thinking, when he tailors sequences of activities so that improvisation and flexible response are activated as an expected part of the day's adaptive response" (Weick & Roberts, 1993: 370). They continue: "the bos'n does not plan specific step-by-step operations but, rather, plans which crews will do the planning and deciding, when, and with what resources at hand."

This picture of a leader's involvement in coordination suggests that he or she would be

28 responsible for designing and being continuously aware of the mental map of the group's operations. Such knowledge would be based in situation awareness, where actors are mindful of the elements in the environment within which they are coordinating, e.g. the actions and needs of others (Endsley, 1988; Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 1999). In the course of performing coordination, this situation awareness is based on dynamic mental models of the state of the group, which is continuously updated based on the changing needs and actions of group members (Rico, Sanchez-Manzanares, Gil & Gibson, 2008). While a ship's bos'n may tend to check on the progress of tasks as they are completed, an example from another unique case of collective work - a choir and its conductor - better describes how the leader continuously guides and re-presents for the group the state of its coordinated activities. In an exploratory ethnographic study, the conductor was observed to plan out the sequence of actions in a rehearsal, and to modify the musical notation prescribed for each vocal section (Stephens, 2010).

The conductor's gestural and verbal expressions that accompanied the choir's performance not only guided the tempo, volume and pitch of performance, but also helped individual singers to recognize whether their interrelation of sounds was beautiful or not. Unlike the bos'n, the conductor served as a continuously accessible source of feedback for the entire group as its members coordinated and not just before or after the performance of coordination.

Out of the myriad theoretical perspectives on leadership found in the organizational studies literature, these examples of leaders in coordination within groups are best linked to social identity perspectives on leadership. Such a perspective is most relevant since it explicitly deals with leadership as a quality of group membership, rather than as a quality of the individual traits a leader might possess (Hogg & Van Knippenberg, 2003). In short, these perspectives describe how, when the salience of group membership is high, individuals emerge as leaders who

29 seem to possess the qualities that are most desirable or prototypical of the group, such as aspirations, values, and behaviors. The social attractiveness of these characteristics makes others readily conform to the behaviors and beliefs of these individuals (Hogg, 2000; Hogg & Terry,

2001). However, in coordination, leaders must be simultaneously representative of the multiple divisions of labor under their purview, be they firefighting, mechanics and cargo rigging in the case of a bos'n, or singing the notes for soprano, alto, tenor, and bass sections in the case of a conductor. These individuals would not be effective leaders if they were not adept at developing the "syntax" needed to communicate effectively across multiple boundaries (Kellogg, Orlikowski

& Yates, 2006). This quality of leadership is important since the context of coordination causes members of various sub-groups to encounter each other raising the salience of their unique memberships (Dougherty, 1992; Heath & Staudenmayer, 2000); the research so far would suggest that an effective leader needs to knowingly represent the superordinate system to each individual sub-group or specialty in order to circumvent bias and discrimination.

This brief review suggests multiple questions ripe for exploration. First, we do not know about the generalizability of this perspective on leaders in coordination: are managers and others in leadership positions generally concerned with effectively representing the system to various sub-groups? Second, we do not know how this representation would occur: while a bos'n may possibly assign tasks for the day via verbal or written orders, and a conductor uses speech, gesture (and even writing) to communicate the quality of the group's coordination, are these the only effective media, and when are they best employed?

Method

In this paper, I will present data from in-depth qualitative interviews with leaders of performative groups, viz. orchestral and choral conductors, and leaders of formal work

30 organizations, viz. managers and team leaders. Large musical ensembles present unique contexts in which mechanisms of coordination are readily accessible for study. Research on orchestral conductors suggests that their involvement in coordination is readily apparent (Marotto, Roos &

Victor, 2007), since “expressive signs which fail to communicate a sum total of information which allows members to engage in lines of action and interaction can have little, if any, authoritativeness within the orchestra” (Faulkner, 1973: 150).

Potential contributions

This research can potentially make at least three main contributions to our understanding of leadership and coordination. First, the current study takes a different stance from a relational view of leadership in which there is reciprocal interrelating between workers and managers regarding what is to be done and how best to do it (Gittell & Douglass 2012). Rather, instead of having the responsibility of leadership shot through the entire group or organization, the current perspective explores the extent to which a leader can encompass the entire group in her thoughts and actions. Second, this study should add to our understanding of the role of leader as boundary spanner in coordination, and the role of communication. Those in managerial roles may find themselves as boundary spanners, but this research suggests that developing an aptitude for communicating clearly across multiple groups (and not just between two) is especially important for coordination. Finally, this research re-specifies the applicability of social identity-based theories of leadership to organizations. Successfully embodying the entire system or organization for various kinds of group members would involve being most representative of multiple groups simultaneously, which would require unique skills and contextual factors.

31 REFERENCES

Ancona, D. & Bresman, H. 2007. X-teams: How to build teams that lead, innovate and

succeed. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Antonakis, J., Avolio, B.J., & Sivasubramaniam, N. (2003). Context and leadership: An

examination of the nine-factor full-range leadership theory using the Multifactor

Leadership Questionnaire. The Leadership Quarterly, 14: 261-295.

Balkundi, P., &Kilduff, M. 2006. The ties that lead: A social network approach to leadership.

The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 419-439.

Barge, J.K. (2004). Reflexivity and managerial practice. Communication Monographs. 71(1).

Bateson, G. (1972) Steps to an ecology of mind. University of Chicago Press.

Bateson, G. (1979) Mind and nature: A necessary unity. Wildwood House, London.

Bechky, B. A. 2003. Sharing meaning across occupational communities: The transformation of

understanding on a production floor. Organization Science, 14(3): 312-

330.

Bechky, B.A. 2006. Gaffers, gofers, and grips: Role-based coordination in temporary

organizations. Organization Science, 17: 3-21.

Bennis, W., & Biederman, P. A. (1997). Organizing genius: The secrets of creative

collaboration. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books.

Bennis,W. 2009. On becoming a leader (3rd edition). Perseus Books (October 1989).

Berg, J. M., Grant, A. M., & Johnson, V. 2010. When callings are calling: Crafting work and

leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organization Science, 21: 973-

994.

Campbell, D. T. 1965. Variation and selective retention in socio- cultural evolution. H. R.

32 Barringer, G. I. Blanksten, R. Mack, eds. Social change in developing areas.

Schenkman, Cambridge, MA, 19–49.

Campbell, D. T. 1997.From evolutionary epistemology via selection theory to a sociology of

scientific validity. Evolution Cognition 3(1) 5–38.

Carson, JE, Tesluk, PE & Marrone, JA (2007). Shared leadership in teams: an investigation of

antecedent conditions and performance. Academy of Management Journal 50 (5):

1217-1234.

Cecchin, G., Ray, W.A. & Lane, G. (1992). Irreverence, a strategy for therapists.

Cecchin, G. (1987) Hypothesising, circularity and neutrality revisited: An invitation to curiosity.

Family Process 26 405-413.

Cooperrider, D. L., & Whitney, D. (2000) A positive revolution in change: Appreciative

Inquiry. In: Cooperrider, D. L., Sorensen, Jr., P. F., Whitney, D. &Yaeger, T. F. (Eds.),

Appreciative Inquiry: Rethinking human organization toward a positive theory of

change (pp. 3-28). Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing.

Cooperrider, D.L. & Srivastva, S. (1987) Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In Pasmore

W.A. & Woodman, R.W. (Eds.) Research in organizational change and development

(vol. 1, pp.129-169). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Cooperrider, D.L., & Whitney, D. (1999). Appreciative inquiry. San Francisco: Berrett-

Koehler.

Davies, B. &Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: the Discursive Production of Selves, I: Journal for

the Theory of Social Behaviour, 20/1.

Day, D.V., Gronn, P., & Salas, E. (2006). Leadership in team-based organizations: On the

threshold of a new era. The Leadership Quarterly 17, 211-216.

33 de Lima, J.A., (2008) Department networks and distributed leadership in schools. School

Leadership & Management, 28(2), 159-187.

DiMaggio, P. (ed.), 2001. The 21st century firm: Changing economic organizations in

international perspective. Princeton University Press, NJ.

Drath, W. (2001). The deep blue sea: Rethinking the source of leadership. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass & Center for Creative Leadership.

Dougherty, D. 1992. Interpretive barriers to successful product innovation in large firms

Organization Science, 3(2): 569-590.

Douglass, A. & Gittell, J.H. 2012. Transforming professionalism: Relational bureaucracy and

parent-teacher partnerships in child care settings. Journal of Early Childhood Research,

forthcoming.

Dutton, J.E. & Ragins, B.R. 2007. Exploring positive relationships at work: Building a

theoretical and research foundation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Ehrlbaum Associates.

Dutton, J.E. & Heaphy, E.D. 2003. The power of high-quality connections. In K.S. Cameron,

J.E. Dutton, R.E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a

new discipline. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Eisenhardt, K. &Graebner, M., 2007. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges.

Academy of Management Journal 50(1): 25-32.

Endsley, M.R. 1988. Design and evaluation for situation awareness enhancement. In

Proceedings of the Human Factors Society 32nd Annual Meeting: 97-101.

Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors Society.

Fairhurst, G. (2007). Discursive leadership: In conversation with leadership psychology.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

34 Faulkner, R. R. 1973. Orchestra interaction: Some features of communication and authority in

an artistic organization. Sociological Quarterly, 14:147-157.

Fletcher, J. K. (2004). The paradox of postheroic leadership: An essay on gender, power, and

transformational change. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(5), 647-661.

Fletcher, J. K. 1999. Disappearing acts: Gender, power, and relational practice at work.

Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fletcher, J. K. 2007. Leadership, power, and positive relationships. In J. E. Dutton, & B. R.

Ragins (Eds.), Exploring positive relationships at work: Building a theoretical and

research foundation: 347-371. New York: Psychology Press

Foldy, E. G., Goldman, L., & Ospina, S. (2008). Sensegiving and the role of cognitive shifts in

the work of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 19, 514-529.

Follett, M.P. 1949. Freedom and co-ordination: Lectures in business organization by Mary

Parker Follett. London: Management Publications Trust, Ltd.

Gauthier, V. 2010. Le Savoir-Relier, in Les Sept Clés du Leadership, (The seven keys of

leadership) Edition L’Archipel.

Gauthier, V. 1994. Approchethéoriqueetpratique de la traductionpoétique à travers la

poésied'Elizabeth Bishop (theoretical and practical approach to poetic transaltion

through the example fo E. Bishop’s poetry”) Unpublished dissertation, Sorbonne

University, Paris, France.

Gauthier, V. Larçon, JP, Lendrevie, J. 1994.“Le Savoir Relier “, in L'Ecole des Managers de

Demain, Economica.

Gergen, K. (2009). An invitation to social construction. (2nd Ed.) Sage.

Gergen, K. (2010). Relational being. Oxford University Press.

35 Gilligan, C. 1982. In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gittell, J.H. & Douglass, A. 2012. Relational bureaucracy: Beyond bureaucratic and relational

organizing. Provisionally accepted, Academy of Management Review.

Gioia, D. A., K. Chittipeddi. 1991. Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation.

Strategic Management J. 12 433–448.

Gioia, D. A., A. Mehra. 1996. Book review: Sensemaking in Organizations. Acad. Management

Rev. 21(4) 1226–1230.

Gioia, D. A., J. B. Thomas. 1996. Identity, image, and issue interpretation: Sensemaking during

strategic change in academia. Admin. Sci. Quart. 41: 370–403.

Gioia, D. A., M. Schultz, K. Corley. 2000. Organizational identity, image, and adaptive

instability. Acad. Management Rev. 25 63–81.

Gioia, D. A., J. B. Thomas, S. M. Clark, K. Chittipeddi. 1994. Symbolism and strategic change

in academia: The dynamics of sensemaking and influence. Organ. Sci. 5 363–383.

Graham, P. 1995. Mary Parker Follett: Prophet of management. Boston, MA: Harvard

Business School Press.

Graen, G., & Scandura, T.A. (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. In B.M.

Stawand L.L. Cummings (Eds.). Research in organizational behavior 9, 175-208).

Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Graen, G., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of

leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-

level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219-247.

36 Gronn, P. (1999). Substituting for leadership: The neglected role of the leadership couple. The

Leadership Quarterly, 10, 41-62.

Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(4),

423-451.

Hammond, S. (1996). The thin book of appreciative inquiry. Kodiak Consulting. Plano.

Harré, R. & van Langenhove, L. (eds.) (1999). Positioning theory: Moral contexts of

intentional action. Malden: Blackwell.

Hargadon, A. B., & Bechky, B.A. 2006. When collections of creatives become creative

collectives: A field study of problem solving at work. Organization Science,

17(4): 484-500.

Hennan, D. A., & Bennis, W. (1999). Co-leadership: The power of great partnerships. New

York: Wiley.

Heracleous, L. 2003. A comment on the role of metaphor in knowledge generation. Academy of

Management Review, 28(2): 190.

Hiller, N. J., Day, D. V., & Vance, R. J. (2006). Collective enactment of leadership roles and

team effectiveness: A field study. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 387-397.

Hollander, E. P. (1964). Leaders, groups, and influence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hornstrup, C. &Loehr-Petersen, J., (2003) Appreciative inquiry. DJOEF Publishing.

Hornstrup, C., Tomm, K. & Johansen, T. (2009). Questioning expanded and revisited. Journal

of Work Psychology.

Hosking, D. M., Dachler, H. P., &Gergen, K. J. (Eds.). (1995). Management and organization:

Relational alternatives to individualism. Brookfield USA: Avebury.

37 Hogg, M.A. 2001. A social identity theory of leadership. Personality and Social Psychology

Review, 5: 184-200.

Hogg, M. A., & Terry, D. J. 2000. Social identity and self-categorization processes in

organizational contexts. Academy of Management Review, 25: 121-140.

Hogg, & Van Knippenberg, D. 2003. Social identity and leadership processes in groups.

Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 35: 1-52.

Keenoy, T., Oswick, C., & Grant, D. 2003.The edge of metaphor. Academy of Management

Review, 28(2): 191.

Kellogg, K.C., Orlikowski, W., & Yates, J. 2006. Life in the trading zone: Structuring

coordination across boundaries in post-bureaucratic organizations. Organization

Science, 17(1): 22-44.

Lang, P., Little, M.,&Cronen, V. (1990). The systemic professional domains of action and the

question of neutrality. Human Systems, 1 39-55. Leeds: LFTRC and KCC.

Lipman-Blumen, J. 1992. Connective leadership: Female leadership styles in the 21stcentury

workplace. Sociological Perspectives, 35(1): 183-203.

Long Lingo E., O’Mahony S. 2010. Nexus Work: Brokerage on Creative Projects.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 55 (2010): 47–81.

Louis, M. R. 1980. Surprise and sensemaking: What newcomers experience in entering

unfamiliar organizational settings. Admin. Sci. Quart. 25 226–251.

Maturana, H. R. & Varela, F.J. (1987) The tree of knowledge. Shambhala Publications.

Maturana, H. & Poerksen, B. (2004). From being to doing. Karl Auer.

Marotto, M., Roos, J., & Victor, B. 2007. Collective virtuosity in organizations: A study of peak

performance in an orchestra. Journal of Management Studies, 44(3): 388-413.

38 McGregor, D. 1960. The human side of enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mallarmé, S. 1876. Les Mots Anglais, in Œuvrescomplètes, Paris: Gallimard « Pleiade » (1965).

Magala, S. J. 1997.The making and unmaking of sense. Organ. Stud. 18(2) 317–338.

Mandler, G. 1984. Mind and body. Free Press, New York.

Marshak, R. J. 2003. Metaphor and analogical reasoning in organization theory: Further

extensions. Academy of Management Review, 28(1): 9-10.

Meindl, J.R. (1995). The romance of leadership as a follower-centric theory: a social

constructionist approach. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(3): 329-341

Meschonnic, H. (1971) Pour la Poétique I,

Mezias, J. M., W. H. Starbuck. 2003. Managers and their inaccurate perceptions: Good, bad or

inconsequential? British J. Management 14(1) 3–19.

Mills, J. H. 2003. Making sense of organizational change. Routledge, London, UK.

Montuori, A. 2005.Gregory Bateson and the challenge of transdisciplinarity. Cybernetics and

Human Knowing, 12(1-2), 147-158(112).

Morgan, G. (1997). Imaginization. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA.

Morgan, G. 1980. Paradigms, metaphors, and puzzle solving in organization theory.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(4): 605-622.

Morgan, G. 1997. Images of Organization (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Morin, E. 1981. La méthode. 1. La nature de la nature [Method. 1. The nature of nature]. Paris:

Seuil.

Morin, E. 1983. Beyond determinism: The dialogue of order and disorder. SubStance (40): 22-

35.

Morin, E. 1985. La Méthode, tome 2. La vie de la vie [Method, volume 2. The life of life]. Paris:

39 Seuil.

Morin, E. (Ed.). 1999. Relier les conaissances: Le défi du XXIe siècle [Reconnecting

knowledge: The challenge of the 21st century]. Paris: Seuil.

Morin, E. 2001. Seven complex lessons in education for the future. Paris: UNESCO.

Morin, E. 2008. On complexity. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Morin, E., & Le Moigne, J.-L. 1999. L'intelligence de la complexité. Paris: L'Harmattan.

Mossholder, K.W., Richardson, H.A., Settoon, R.P. 2011. Human resource systems and helping

in organizations: A relational perspective, Academy of Management Review, 36:1: 33-

52.

Orton, J. D. 2000. Enactment, sensemaking, and decision making: Redesign processes in the

1976 reorganization of US intelligence. J. Management Stud. 37 213–234.

Oswick, C., Keenoy, T., & Grant, D. 2002. Metaphor and analogical reasoning in organisational

theory: Beyond orthodoxy. Academy of Management Review, 27(2): 294-303.

Oswick, C., Keenoy, T., & Grant, D. 2003. More on metaphor: Revisiting analogical reasoning

in organization theory. Academy of Management Review, 28(1): 10-12.

Ospina, S. & Uhl-Bien, M. (in press) Competing Bases of Scientific Legitimacy in

Contemporary Leadership Studies. In Uhl-Bien, M. & S. Ospina (Eds.) Advancing

relational leadership theory: A dialogue among perspectives. Charlotte NC:

Informational Age.

Ospina, S. & Sorenson, G. (2006) A constructionist lens on leadership: Charting new territory. In

In quest of a general theory of leadership, eds. G. Goethals, G. Sorenson, 188-204.

Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar

40 Pascal, B. 1669.Pensées (Thoughts, translated by T.S. Eliot, 1958, NY:EPDutton&Co). Pearce,

C. L., & Conger, J. A. (2003). Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of

leadership. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Pearce, W. B. (2004) Using CMM.www.pearce-associates.com.

Pearce, W.B. (2008), Kommunikationogskabelsenafsocialeverdener. PsykologiskForlag.

Rico, R., Sanchez-Manzanares, M, Gil, F., & Gibson, C. 2008. Team implicit coordination

processes: A team knowledge-based approach. Academy of Management Review,

33(1): 163-184.

Sally, D. 2002. Co-leadership: Lessons from Republican Rome. California Management

Review, 44: 84-99.

Shamir, B., Pilai, M., Bligh, M., &Uhl-Bien, M. (Eds.). (2007). Follower-centered perspectives

of leadership. Greenwich CT: Information Age Publishing.

Spillane, J.D. 2006. Distributed leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schein, E. 2009. Helping: How to offer, give and receive help. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Stephens, J.P. 2010.Towards a psychology of coordination: Exploring feeling and focus in the

individual and group in music-making. Dissertation, University of Michigan.

Tannenbaum, A. 1968. Control in organizations. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Taylor, F.W. 1911. Scientific management. New York: Harper and Row.

Taylor, J. R., E. J. Van Every. 2000. The emergent organization: Communication as its site

and surface. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Tomm, K. (1988). Interventive interviewing part III. Family Process, 27(1): 1–15.

Tsoukas, H. 1991. The missing link: a transformational view of metaphors in organizational

science. Academy of Management Review, 16(3): 566.

41 Tsoukas, H. 1993. Analogical Reasoning and Knowledge Generation in Organization Theory.

Organization Studies, 14(3): 323.

Tsoukas, H., R. Chia. 2002. Organizational becoming: Rethinking organizational change.

Organization Science 13(5) 567–582.

Turbayne (1962). The myth of metaphor, introduction by Hayakawa.

Uhl-Bien, M, R. Marion, B. McKelvey. 2007. Complexity leadership theory: shifting leadership

from the industrial age to the knowledge era. The Leadership Quarterly 18, 298 – 318

Uhl-Bien, M. (2006). Relational leadership theory: Exploring the social processes of leadership

and organizing. The Leadership Quarterly 17, 654-676

Uhl-Bien, M. & Ospina, S. (Eds.) (in press). Advancing relational leadership theory: A

dialogue among perspectives. Charlotte NC: Informational Age

Weber, M. 1920/1984. Bureaucracy. In F. Fischer & C. Sirianni (Eds.), Critical studies in

organization and bureaucracy: 24-39. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Weick, K. E., & Roberts, K. H. 1993. Collective mind in organizations: heedful interrelating on

flight decks. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38: 357-381.

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. 1999. Organizing for high reliability: processes of

collective mindfulness. Research in Organizational Behavior, 21: 81-123.

Weick, K. E. 1995. Sensemaking in organizations. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Weick, K. E., K. M. Sutcliffe. 2001. Managing the Unexpected. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld. 2005. Organizing and the process of sensemaking, Organization

Science 16(4), pp. 409–421.

Wrzesniewski, A. & Dutton, J.E. 2001. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters

of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2): 179-2.

42