Beyond Cyclical Change: Implications for the Minimalist Program Elly van Gelderen Explaining Language Change, Tucson, 26 March 2011

I will review examples of major linguistic cycles, the head marking cycle (e.g. from subject and object pronoun to agreement) and the dependent marking, and explain what insight they give to current syntactic research. I then list some challenges the cycles present for the Minimalist Program.

What is the linguistic cycle? Examples of major linguistic cycles: the head marking cycle (from subject and object pronoun to subject and object agreement and copulas) and the dependent marking cycle

Pronoun > agreement (1) Se je meïsme ne li di Old French If I myself not him tell `If I don’t tell him myself.’ (Franzén 1939:20, Cligès 993) (2) a. Je lis et j'écris French I read and I-write `I read and write.’ b. *Je lis et écris I read and write (3) Moi je suis pour un impôt sur les sociétés qui taxerait … French `Me, I am for a tax on companies that would tax …’ (http://www.metrofrance.com/info/francois-hollande-aujourd-hui-je-suis- pret/mkco!Uh9yvIt3B7cL2)

Demonstrative > article > Case König (2008: 117) for West Nilotic, Sasse (1984) for Berber, Kulikov (2006: 29-30) for Kartvelian, Georgian, and Caucasian, McGregor (2008) for Australian languages and Mithun (2008) for Wakashan.

Examples of minor cycles: future and aspect cycles and the negative cycle. (4) a. I told Cowslip we were going before I left the burrow. (BNC-EWC 3181) b. Anne can HAVE her Mini....Cause I's gonna get me a BMW (http://www.inkycircus.com/jargon/2006/09/anne_can_have_h.html)

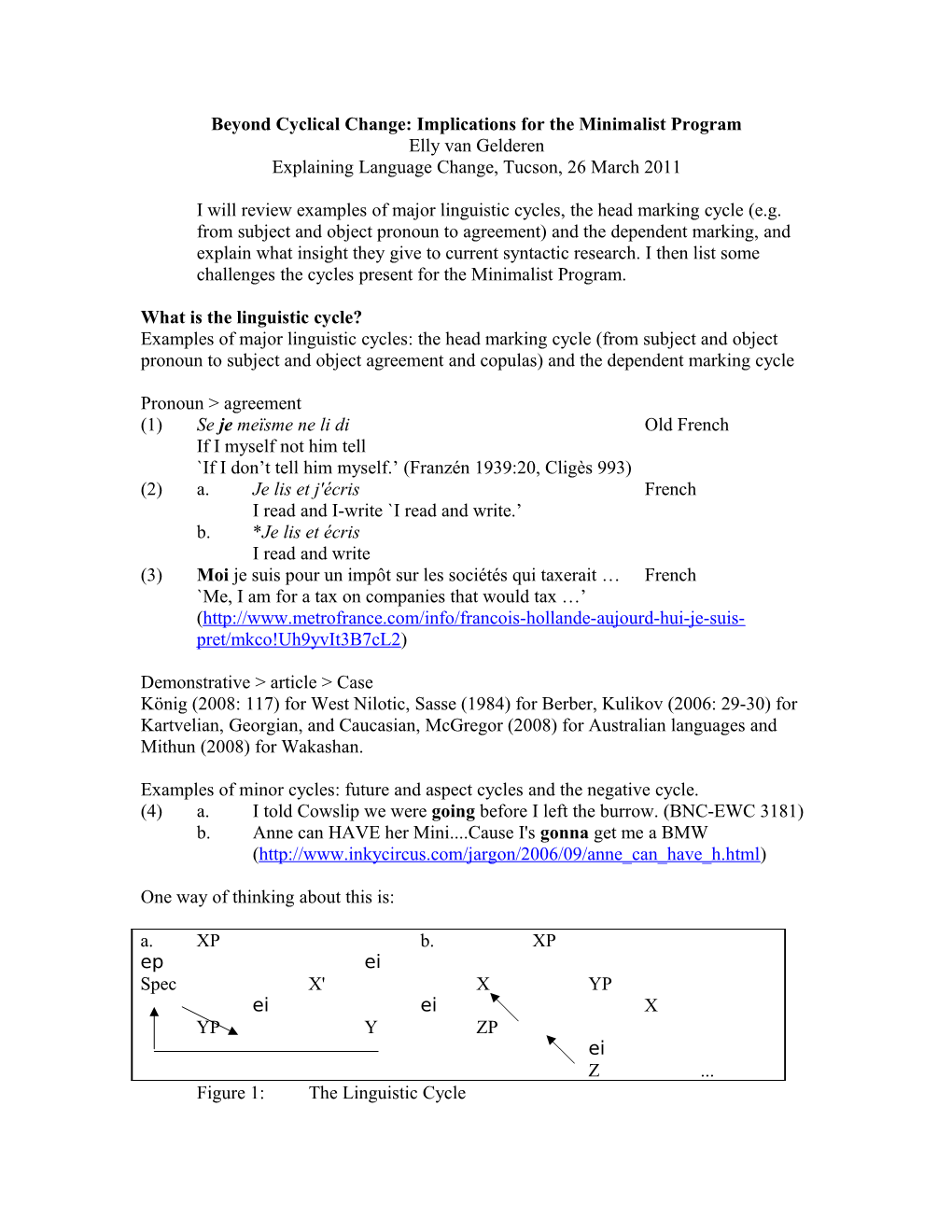

One way of thinking about this is: a. XP b. XP ep ei Spec X' X YP ei ei X YP Y ZP ei Z ... Figure 1: The Linguistic Cycle Earlier work on the cycle: de Condillac (1746), Tooke (1786-1805), Bopp (1816), von Humboldt (1822), and then Tauli (1958), Hodge (1970), Greenberg (1978), Givón (1978), and Katz (1996).

However: Robin Lakoff wrote that "there is no mechanism within the present theory of transformational grammar that would allow an explanation" (1972: 173-4) and even outright rejection of the idea of linguistic cycles, e.g. Newmeyer (1998: 263-275; 2001) and Lightfoot (e.g. 2006a: 38).

My aim: examine examples and explore what the typical steps in the cycles are, where they start, and how they renew themselves: a. The subject cycle is driven by phi-features; it starts with first and second person. b. The object cycle does not start as uniformly as the subject cycle. It is driven by animacy and or deictic features. c. Polysynthetic languages do not employ uninterpretable phi-features which distinguishes them from others d. Copulas consist of locative features. They therefore grammaticalize from three sources, demonstrative, locative verbs, and adpositions. e. Dependent marking of grammatical roles is definiteness marking. f. Differential Object Marking is (still) a mysterious phenomenon. There is some evidence that it is really definiteness marking. g. Inherent Case is represented by interpretable features such as time and place. Structural uninterpretable Case on subjects is checked by T (as in Pesetsky & Torrego 2001) and on objects by ASP/v. h. The position of the NegP is variable. Cyclical change indicates that there is perhaps always a Pol(arity)Phrase in the expanded CP since negatives are often reanalyzed as very high elements. i. TMA cycles are very varied. Sources: adverbs, PPs, demonstratives. Table 1: Some conclusions from looking at cyclical change (van Gelderen in press)

What happens? Feature change: (5) semantic > [iF] > [uF] > [uF] (Adjunct Specifier Head affix)

Loss of semantic features occurs when full verbs such as Old English will with features such as [volition, expectation, future] are reanalyzed as having only the feature [future] in Middle English. The features can then be considered grammatical rather than semantic, as in (6) with for:

(6) a. hlynode for hlawe made-noise before mound ‘It made noise before/around the gravehill.' (Beowulf 1120). b. I would prefer for John to stay in the 250 class. (BNC-ED2 626)

I build on Chomsky's (1995: 230; 381) insight that "formal features have semantic correlates and reflect semantic properties (accusative Case and transitivity, for example)."

(7) Subject Agreement Cycle emphatic > full pronoun > head pronoun > agreement [i-phi] [i-phi] [u-1/2] [i-3] [u-phi]

Some conclusions: Agreement seems to be central (although a few languages show no signs of grammaticalizing their pronouns). Case is much more of a mix of dependent marking for semantic, grammatical, and pragmatic reasons. Features matter and change is (mostly) uni-directional.

Challenges for the features of the Minimalist Program:

I. Languages that may not have u-phi: PALs (as in Jelinek’s and Willie’s work) and highly analytic languages.

II. No necessary connection between Case and agreement.

Agreement no Agreement Case Yaqui, Amis, Urdu, Basque Japanese, Korean, Khoekhoe no Case Navajo, Zulu, Lakhota, Ainu Sango, Haida, (French), Thai, Haitian Creole Table 2: Languages with and without Case and agreement

Baker expresses this as: (8) The Case Dependence of Agreement Parameter (CDAP) F agrees with DP/NP only if F values the Case feature of DP/NP (or vice versa). (Baker 2008: 155)

III. If all parameters are restricted to the lexicon, i.e. to the features postulated, the child will need some guidance as to what to pay attention to. What?

- Feature parameters and an inventory Phi-features (for head-marking) `Case' (T/ASP) (for dependent-marking) ei ei yes no yes no ei Chinese English Navajo u-F i-F Chinese English Navajo Figure 2: Feature Macroparameters Semantic: [loc], [time], [ps], etc

Formal: u-phi, i-phi, u-T, i-T, u-ASP, i-ASP, u-NEG, i-NEG, u-Q, i-Q

[Phi] on English heads: (9) T [u-phi] [i-T] D [u-phi] [u-T] v [u-phi] [i-ASP] N [i-phi] (10) NEG and C heads in English: NEG [u-NEG]; Cwh [u-Q]; C [u-T]

[uF] and [iF]: [T] on C + T [T] on D [phi] on T, V, and N [Q] [NEG] Semantic features as source: [loc] [time] [loc] [person, number, [wh] [negative] gender] [negative] Table 3: Grammatical features and their sources

What’s next? - Irregularities in the Cycle

Isolating

Inflectional Agglutinative Figure 3: Attachment type (Crowley 1992: 170)

- Role of phonology in grammaticalization

Some References (I can e-mail further ones) Baker, Mark 2008. The syntax of Agreement and Concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Crowley, Terry. 1992. An Introduction to Historical Linguistics. Auckland: Oxford University Press. Gelderen, Elly van in press The Linguistic Cycle: Language Change and the Language Faculty. Oxford University Press. Hodge, Carleton 1970. The Linguistic Cycle. Linguistic Sciences: 13: 1-7. Tauli, Valter 1958. The Structural Tendencies of Languages. Helsinki.