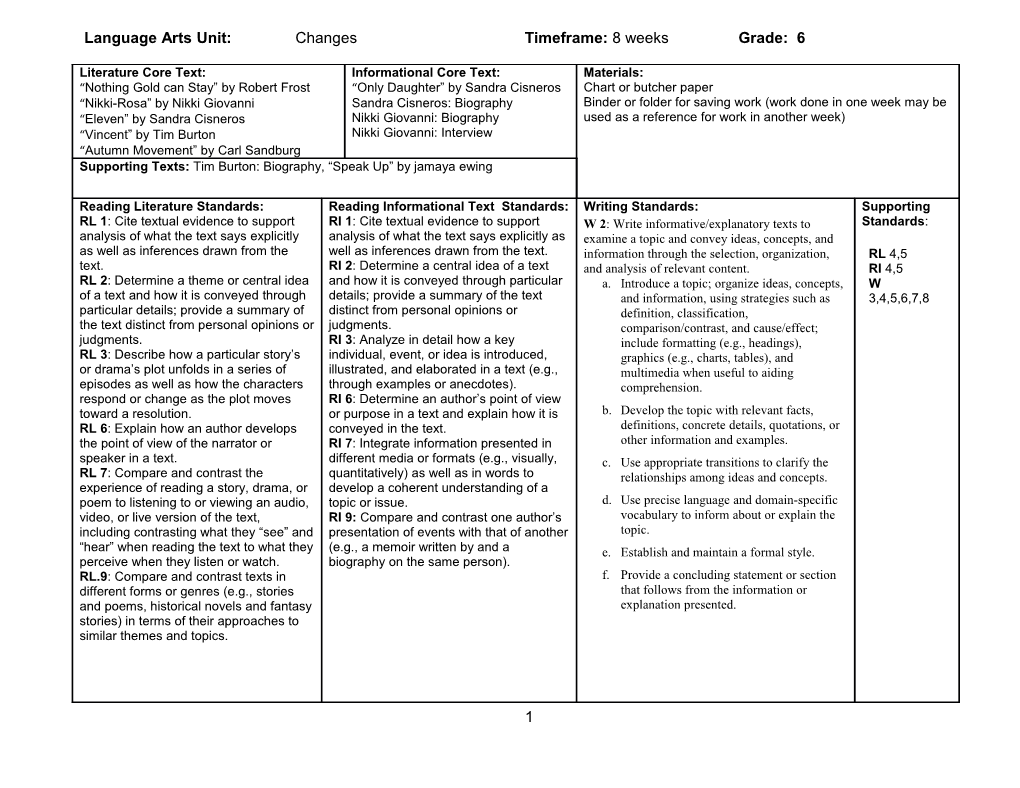

Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Literature Core Text: Informational Core Text: Materials: “Nothing Gold can Stay” by Robert Frost “Only Daughter” by Sandra Cisneros Chart or butcher paper “Nikki-Rosa” by Nikki Giovanni Sandra Cisneros: Biography Binder or folder for saving work (work done in one week may be “Eleven” by Sandra Cisneros Nikki Giovanni: Biography used as a reference for work in another week) “Vincent” by Tim Burton Nikki Giovanni: Interview “Autumn Movement” by Carl Sandburg Supporting Texts: Tim Burton: Biography, “Speak Up” by jamaya ewing

Reading Literature Standards: Reading Informational Text Standards: Writing Standards: Supporting RL 1: Cite textual evidence to support RI 1: Cite textual evidence to support W 2: Write informative/explanatory texts to Standards: analysis of what the text says explicitly analysis of what the text says explicitly as examine a topic and convey ideas, concepts, and as well as inferences drawn from the well as inferences drawn from the text. information through the selection, organization, RL 4,5 text. RI 2: Determine a central idea of a text and analysis of relevant content. RI 4,5 RL 2: Determine a theme or central idea and how it is conveyed through particular a. Introduce a topic; organize ideas, concepts, W of a text and how it is conveyed through details; provide a summary of the text and information, using strategies such as 3,4,5,6,7,8 particular details; provide a summary of distinct from personal opinions or definition, classification, the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments. comparison/contrast, and cause/effect; judgments. RI 3: Analyze in detail how a key include formatting (e.g., headings), RL 3: Describe how a particular story’s individual, event, or idea is introduced, graphics (e.g., charts, tables), and or drama’s plot unfolds in a series of illustrated, and elaborated in a text (e.g., multimedia when useful to aiding episodes as well as how the characters through examples or anecdotes). comprehension. respond or change as the plot moves RI 6: Determine an author’s point of view toward a resolution. or purpose in a text and explain how it is b. Develop the topic with relevant facts, RL 6: Explain how an author develops conveyed in the text. definitions, concrete details, quotations, or the point of view of the narrator or RI 7: Integrate information presented in other information and examples. speaker in a text. different media or formats (e.g., visually, c. Use appropriate transitions to clarify the RL 7: Compare and contrast the quantitatively) as well as in words to relationships among ideas and concepts. experience of reading a story, drama, or develop a coherent understanding of a poem to listening to or viewing an audio, topic or issue. d. Use precise language and domain-specific video, or live version of the text, RI 9: Compare and contrast one author’s vocabulary to inform about or explain the including contrasting what they “see” and presentation of events with that of another topic. “hear” when reading the text to what they (e.g., a memoir written by and a e. Establish and maintain a formal style. perceive when they listen or watch. biography on the same person). RL.9: Compare and contrast texts in f. Provide a concluding statement or section different forms or genres (e.g., stories that follows from the information or and poems, historical novels and fantasy explanation presented. stories) in terms of their approaches to similar themes and topics.

1 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Essential Questions: RL 1 and RI 1 In citing, what is the difference between quoting and paraphrasing? What is an inference? How do readers make an accurate inference based on evidence in the text? RL 2 How do readers figure out the message or moral or theme or underlying meaning of a poem or story? How does a writer develop a theme? How can summarizing help us to better understand text? RL 3 How is the process of reading poetry different from reading stories and dramas? What is important to notice about characters and events in a story or poem? How do the characters in the story and the plot work together? RL6 How does a poet develop the point of view of the narrator/speaker? How does point of view affect the meaning of text? RL7 How do the elements of poetry work to impact text? How do the elements of poetry work to impact a live version/audio/video of text? How is a play similar to and different from prose and poetry? RL 9 How do different genres support similar themes? RI 2 What do good readers do to help them understand what they are reading? RI 3 How are authors’ ideas developed by particular sentences, paragraphs, or larger portions of informational text? How does the structure of informational text contribute to the development of ideas? How do readers connect ideas about a topic after they read? RI 7 How do we use different sources to help in understanding a topic? RI 9 How do authors develop point of view? How can various authors interpret events differently? W2

2 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

How is a topic introduced in explanatory writing? How are concepts and information used and organized to support the topic? What are the best strategies to use to explain the topic?

Summative Unit Assessments:

Literature: Writing Prompt (W2) Write an informative/explanatory multi-paragraph essay comparing and contrasting the short story “Eleven” by Sandra Cisneros to the poem “Nikki-Rosa” by Nikki Giovanni. Use the following guidelines: 1. Focus the essay on the similarities and differences in how the authors develop the theme and the point of view of the narrators. 2. Introduce and state a topic. 3. Organize a body of two or three paragraphs to support the topic. 4. Use the similarities-to-differences strategy (a variation of the point-by-point method) to organize and format the essay. a. Compare themes & points of view (1-2 paragraphs) b. Contrast themes & points of view (1-2 paragraphs) 5. Use citations and evidence from the pieces. 6. Provide a conclusion. The following graphic organizers can be used to assist in the writing process: “Compare & Contrast: Similarities-to-Differences Strategy”, Appendix A, pp.30 & 31 and VENN Diagram, Appendix A, p.35

3 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Teacher Background Knowledge/Key Information about this Unit: The unit has been revised to reflect the consensus of the ELA facilitators at our meeting on February 17. The theme of change remains, so you can tie all of the readings back to it throughout the unit. Instead of reading about Egypt for the informational text in the first two weeks, you will find links to articles about environmental change and wolves, and two poems that deal with change as a theme. Week three will entail a biography and interview about Nikki Giovanni. Week four remains the same, reading the poem, “Nikki Rosa.” There has been a change in week five so that students will now read the poem “Vincent.” Week six will provide students the opportunity to do a close read on a memoir and a biography on Sandra Cisneros as well as a writing task. In week seven, students will again read, “Eleven”. Week eight is reserved for the summative writing task, which is the same as last year’s. The priority, according to the 6th grade ELA facilitators, was to change the informational text portion and be extended some choice about what to read with their class. This was accomplished in the first week by providing 3 groupings of articles to choose from. 2 groups of articles about environmental change/climate change are offered. One collection has easier text and the other set has more challenging text. The 3 rd group of articles comes from the ODELL unit: The Wolf You Feed. Choose whichever group of articles suits your needs. The tasks are written generically, so that they can be used with any of the articles. Again, the choice is up to you as far as which tasks you choose. The challenge came when trying to figure out how to print classroom sets of the articles when all teacher s will not be reading the same set. Therefore, teachers will need to copy their own articles for the first week. All other texts will be copied for you at the district and sent to your site. As you can see, there is more prep work for you to do ahead of starting the revised unit. To support the standards effectively, you will notice that informational text and literature are intertwined as opposed to doing the informational text first and then the literature piece. You will notice a decreased amount of tasks in most of the weeks. This is to accommodate the days that testing for SBAC will take place. Please note that a decrease in the amount of tasks does not decrease the rigor and expectations of the tasks that are required. If you find that you are running of out materials and the students are completing all tasks with mastery, please refer back to week one and choose another piece of informational text to read. There are many opportunities for close reading in this unit. Keep in mind that not all close reading protocols are the same. Instead, they are dependent upon the type of text being read and the content which is essential for that given piece. If students get confused remind them that they read different texts for different reasons and therefore the strategies they use during close reading will be different with different texts. Students need to know why they are reading something. Teachers need to identify what they want students to know or understand about the reading when they get done. As teachers, we need to provide our students with a focus or purpose for reading. Multiple opportunities are woven throughout the unit to practice informational writing (specifically compare/contrast) before the summative. You will need to teach this type of writing to your students (Identifying similarities and differences is one of the most effective strategies to raise students achievement (Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001). Here are three strategies to organize comparison and contrast papers: 1. Whole-to-Whole, or Block In this structure, you say everything about one item then everything about the other. For instance, say everything about the presentation and/or what the student experiences regarding the characters, setting, structure and/or plot for the read poem and then everything about the same for the video. Whole-to-Whole comparison and contrast uses a separate section or paragraph for each item you're discussing. The points in each of the sections should be the same and they should be explained in the same order (for instance, you might discuss the presentation of the character, setting, and plot for both, and in that order for both). 2. Similarities-to-Differences In this structure, you explain all the similarities about the items being compared and then you explain all the differences. For instance, you might explain that the presentation and/or what the student experiences regarding the characters and plot were similar in both the poem and video in the one section. In the next section, you could explain that the presentation and/or what the student experiences regarding the characters and the plot 4 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

were different. Similarities-to-Differences comparison and contrast uses a separate section or paragraph for similarities and differences. In other words, the body of your paper would have two large sections: one for similarities, and another for differences. 3. Point-by-Point In this structure, you explain one point of comparison before moving to the next point. For instance, you would write about the presentation and/or the student experiences regarding the characters in the poem and video in one section; then you would write about the presentation and/or the student’s experiences regarding the setting in the poem and video in the next section. Point-by-Point comparison and contrast uses a separate section or paragraph for each point. For consistency, begin with the same item in each section of your point-by-point paper.

5 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Week 1: Informational Text Standards: Learning Targets: RI 1: Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well RI 1: Orally and in writing, students will cite several details and as inferences drawn from the text. examples to support not only what the text explicitly says but through RI 2: Determine a central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through particular drawing inferences. details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments. RI 2: Students will distinguish between objectivity and subjectivity in RI 3: Analyze in detail how a key individual, event, or idea is introduced, illustrated, the text as well as objectively summarizing the text. and elaborated in a text (e.g., through examples or anecdotes). RI 3: Orally and in writing, students will analyze, in detail, how RI 6: Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and explain how it is individuals, events or ideas in a text are introduced and change over the conveyed in the text. course of the text. RI 7: Integrate information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, RI 6: Students will determine an author’s point of view in an quantitatively) as well as in words to develop a coherent understanding of a topic or informational text as well as how the author uses supporting details to issue. support that point of view. Orally and in writing, students will explain RI 9: Compare and contrast one author’s presentation of events with that of another how the point of view is conveyed in a text by evaluating what (e.g. a memoir written by and a biography on the same person.). information the author chooses to present, statements used within the W 2: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas, concepts, and text and the use of language. information through the selection, organization, and analysis of relevant content. RI 7: Given multiple sources of information, students will chart (2a,b,c,d,e,f) information from those sources to present a coherent understanding of a topic. Students will present their understanding both orally and in writing. RI 9: Students will compare how different authors portray the same idea or event. W 2: With the use of a graphic organizer, students will write a formal, informative multiple paragraph piece to examine a topic. Students will support the topic with important information and use various strategies to examine the information about the topic. Teacher Background Knowledge/Key Information Week 1: You will find 3 sets of articles to choose from this week. Two groups of articles are about environmental change/climate change. One collection has easier text and the other set has more challenging text. The 3rd group of articles comes from the ODELL unit: The Wolf You Feed. Choose whichever group of articles suits your needs. The tasks are written generically, so that they can be used with any of the articles. Again, the choice is up to you as far as which tasks you choose to use. Please be aware that you will need to copy your own sets of articles for this week.

Informational Text: Please choose one set of articles to use this week. If you choose to read the articles on environmental change, the compare and contrast will be based on how the authors write about the topic of climate change and/or environmental change. If you choose to read the articles on wolves perhaps students will compare how the authors convey that wolves fill an important role in the web of life, or that wolves exhibit a complex web of social relationships, or your own idea!

ReadWorks articles from www.readworks.org **Easier texts Hook, Line, and Sinker: http://www.readworks.org/user/m/login/nojs?destination=passages/hook-line-and-sinker Holy Cow!: http://www.readworks.org/user/m/login/nojs?destination=passages/holy-cow Fuels of the Future: http://www.readworks.org/user/m/login/nojs?destination=passages/fuels-future Dirty Job: http://www.readworks.org/user/m/login/nojs?destination=passages/dirty-job Water from the Air: Cloud Forests: http://www.readworks.org/user/m/login/nojs?destination=passages/water-air-cloud-forests 6 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

High and Dry: http://www.readworks.org/user/m/login/nojs?destination=passages/high-and-dry Life Finds a Way: http://www.readworks.org/user/m/login/nojs?destination=passages/life-finds-way

Scholastic articles from http://www.scholastic.com/home/ **More challenging texts Tomorrow’s Weather: http://www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=7571&print=1 Reefs at Risk: http://www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=7854 Protecting Polar Bears: http://www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=11271 Global Warming Report: http://www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=11487 An Inconvenient Truth for Kids: http://www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=12027 Plight of the Penguins: http://www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=3748563 Antarctica Breaking: http://www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=3749276

Informational texts can also be found in the ODELL unit plan: The Wolf you Feed. You will find a PDF containing all of the texts for the unit by following this link: http://odelleducation.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/RC-Unit-Texts-G6_The-wolf-you-feed.pdf Please use the following titles: A Brief History of Wolves in the United States, by Cornelia N. Hutt All About Wolves: Pack Behavior, by John Vucetich and Rolf Peterson All About Wolves: Hunting Behavior, by John Vucetich and Rolf Peterson Alpha Status, Dominance, and Division of Labor in Wolf Packs, by David L. Mech Optional Websites for your use, if you so choose: Living with Wolves http://www.livingwithwolves.org/index2.html Lobos of the South West http://www.mexicanwolves.org/index.php/about-wolves

Tasks (Remember the tasks are listed as options. Choose the ones you would like to use with your article set.)

Discussion questions (apply to all texts): What is the author’s personal relationship to the topic or themes? What do you learn about the topic as you read? How do the ideas relate to what you already know? How are the details you read about related in ways that build ideas and themes?

Compare and Contrast Chart Graphic Organizers http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson275/compcon_chart.pdf You will also find 2 more compare and contrast graphic organizers (A & B) in Appendix A After your students complete 2 graphic organizers they should write 2 or more compare contrast paragraphs or a multiparagraph essay using their graphic organizers, notes, a prewriting plan and the texts to guide them (RI 1,RI 3 RI 9, W2). Integrating Information from a variety of authors or formats Transmediations (McLaughlin, 2010) provide learners with essential, first-hand understanding of how various formats impact text. Students choose a text in its original format and transform that text into another medium, such as a poem, or an electronic picture book, or song lyrics, or a work of art. This task might be done after students have read all of the articles in the text set you chose. They can choose their favorite article to 7 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

“transmediate.” Glogster (www.edu.glogster.com) is an online tool for creating an interactive multimedia image that looks like a poster, but glog readers can interact with the elements and content. A glog can contain photos, artwork, video clips, text descriptions, symbols, colors, and graphics. Students could use this tool to create posters about what they have read in the article set. Side by Side After students have read and annotated at least 2 of the articles they can place both annotated articles side-by-side and begin to fill in a compare contrast graphic organizer or a Venn diagram. Stop and Jot Students periodically stop and think about information that they are reading and jot down their thoughts. They might stop after each paragraph, each page, or each section of reading. Students may write about something they learned, something they are wondering about, or a prediction about what they might learn next. If students use sticky notes to do this, they can mark the sections of the book or article. Then, the notes can be added to a whole-class chart that will help build content knowledge and understanding. Golden Lines What -This strategy engages readers to look for a specific point that “speaks” to them. "Golden Lines" are powerful quotes that automatically provide interesting discussion material. Why -Many students find it much easier to select something the author said than to come up with their own reactions. Therefore, Golden Lines are an easy and effective strategy for students to determine important ideas, make connections, and visualize during reading. How Think: Have students read an article and choose a golden line – quotations or key statements that have special meaning or strike them as important.

Pair: With a partner, students share their golden lines and discuss their thoughts.

Share: Have students share ideas among table members and share out a few ideas within the room. (Optional: Group students in the room that selected the same/similar passages and have them summarize the passage into 10 words or less)

Critical Reading Strategies Number the paragraphs: Since common core requires students to refer to the text, they can start by numbering the paragraphs to make the text easier to navigate. Chunk the text: When faced with a full page of text, reading it can quickly become overwhelming for students. Breaking up the text into smaller sections (or chunks) makes the page much more manageable for students. Students do this by drawing a horizontal line between paragraphs to divide the page into smaller sections. It is important to understand that there is no right or wrong way to chunk the text, as long as there is justification for why certain paragraphs are grouped together. At first, you might tell your students what paragraphs to chunk. Later, you can let go of that responsibility and ask your students to chunk the text on their own. Underline and circle…with a purpose: Telling students to simply underline “the important stuff” is too vague. “Stuff” is not a concrete thing that students can identify. Instead, direct students to underline and circle very specific things. Think about what information you want students to take from the text, and ask them to look for those elements. What you have students circle and underline may change depending on the text type. Circling specific items is also an effective close reading strategy. If you have students circle “key terms” tell them that they are words that are 1. Defined, 2. Are repeated throughout the text. 3. If you only circled five key terms in the entire text, you would have a pretty good idea about what the entire text is about.

8 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Left margin: What is the author SAYING?: We must be very specific and give students a game plan for what they will write in the margins. This is where the chunking comes into play. In the left margin, ask students to summarize each chunk. You may need to demonstrate how to summarize in 10-words or less. The chunking allows the students to look at the text in smaller segments, and summarize what the author is saying in just that small, specific chunk. Right margin: Dig deeper into the text: Direct students to complete a specific task for each chunk. This may include: Use a power verb to describe what the author is DOING. (For example: Describing, illustrating, arguing, etc..) Note: It isn’t enough for students to write “Comparing” and be done. What is the author comparing? A better answer might be: “Comparing the character of Montag to Captain Beatty”. Represent the information with a picture. This is a good way for students to be creative to visually represent the chunk with a drawing. Ask questions. Students can begin to learn how to ask questions that dig deeper into the text. Try asking them to include one of the following terms in each question: significance, trait, importance, value, purpose, reason, function, causation, change, connection, perspective. Find connections: Ask students to find connections between the events and/or ideas in the text. (adapted from iTeach.iCoach.iBlog.com)

CSI: Color, Symbol, Image What- This strategy asks students to identify and distill the essence of ideas from reading, watching or listening in non-verbal ways by using a color, symbol, or image to represent the ideas. CSI can be used to enhance comprehension of reading, watching or listening. It can also be used as a reflection about previous events or learning. It is helpful if students have had previous experience with highlighting texts for important ideas, connections, or events. The synthesis happens as students select a color, symbol, and image to represent three important ideas. This routine also facilitates the discussion of a text or event as students share their colors, symbols, and images. Why -Good readers sometimes use nonlinguistic representations (pictures instead of words) to identify big ideas while reading. These nonlinguistic representations help readers to infer theme and that inference becomes generative knowledge they can use later to help them make decisions and solve problems. How o As students are reading/listening/watching, they make note of things that they find interesting, important, or insightful. o When finished, students choose 3 of these items that most stand out. o For one of these, they choose a color that they feel best represents or captures the essence of that idea. o For another one, they choose a symbol that they feel best represents or captures the essence of that idea. o For the other one, they choose an image. o With a partner or group, students share their color and then share the item from the reading that it represents. Students tell why they chose that color as a representation of that idea. Repeat the sharing process until every member of the group has shared his or her Color, Symbol, and Image. Adapted From: Visible Thinking ©, Harvard Project Zero Point of View Analyze the text to determine the author’s point of view about the topic. Discuss (or use as a short answer written assignment) How do we know the point of view? How is the author’s point of view conveyed? Is the author’s point of view supported with evidence and (reasons? What was the author’s purpose for writing this article? How do you know? Cite specific details from the text. 9 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Another appealing way for students to focus on point of view or purpose is to use a comic strip generator. There are several free generators available online, such as ToonDoo (www.toondoo.com), Chogger (www.chogger.com) and Make Beliefs Comix (www. makebeliefscomix.com). Students create comic strips using characters, scenes, props, speech and thought bubbles, and captions to explain an author’s purpose for writing a text. When students cerate comic panels to represent the retelling of a story or event and include speech and thought bubbles, they decide what the character or individual might think, say, and do. With your guidance, students can think critically about text by analyzing point of view in order to create comic strips. (McLaughlin, Marueen, Overturf, Brenda J. The Common Core: Teaching Students in Grade 6-12 to Meet the Reading Standards)

Summarize After each article, students should practice writing a summary, distinct from personal opinions or judgments, including a central idea of the text (RI 1 and RI 2).

Enrichment opportunity: If you have learners who are very independent you might consider allowing them to do the following readwritethink lesson with a small group, while you are guiding the rest of the class in other activities. The entire lesson can be found at: http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom- resources/lesson-plans/critical-literacy-action-multimodal-1139.html?tab=3#resources Or, you could simply use the following pieces from the overall lesson: Evaluating Scientific Credibility: http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson1139/evaluating_scientific.pdf Representing Global Warming Discussion Guide: http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson1139/representing_discussion.pdf Self-Evaluation Rubric: http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson1139/representing_rubric.pdf Global Warming: Tying It All Together: http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson1139/global_tying.pdf

10 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Weeks 2: “Autumn Movement” and “Nothing Gold can Stay” Standards: Learning Targets: RL 1: Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly RL 1: Orally and in writing, students will use several citations to support as well as inferences drawn from the text. what a text says explicitly and to make inferences RL 2: Determine a theme or central idea of a text and how it is conveyed RL 2: Orally and in writing, students will determine a theme or central through particular details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal idea of a literary text and describe how the theme is conveyed through opinions or judgments. particular details (character, setting, events); students will provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments

Week 2: Teacher Background Knowledge/Key Information: This week continues to focus on the theme of change but uses poetry to explain both changes in nature as well as personal growth/changes in people. The poem “Autumn Movement” demonstrates change using the transition between Autumn and Winter. Thematically it can be broadened to changes in life as well. The poem, Nothing Gold Can Stay, by Robert Frost does a lot of things well and therefore is a good model for readers who aren’t quite sure what makes a good poem. For one thing, “Nothing Gold Can Stay” is only eight lines long, a few sentences. It is an apt example of the economic use of words. Each word, each sound, is important. Yet in that short space, Frost conveys a theme that is a staple of many works of literature: the inevitability of change. Nothing gold can stay, he tells us. And this is a theme students can relate to. They see change all around them, in their families, in their friends. They study it in science, social studies, and literature. Other poems dealing with change or impermanence that can be used in conjunction with “Nothing Gold can Stay” are:

“Spring Storm,” by Jim Wayne Miller: https://sites.google.com/site/middleschoolpoetryunit/2-craft-and-structure/determining-the-meaning-of-words/spring- storm Junkyards,” by Julian Lee Rayford: https://sites.google.com/site/middleschoolpoetryunit/key-ideas-and-details/determine-a-theme-of-a-story/junkyards “Abandoned Farmhouse,” by Ted Kooser: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/237648 “Deserted Farm,” by Mark Vinz: http://blogs.swa-jkt.com/swa/samanthapryse/2013/05/13/deserted-farm/

Theme is one of the more elusive literary terms to define. Consequently, many young readers have difficulty understanding it and knowing its role in a poem. Some students have been taught that theme is the “meaning” of a poem, “what the poet is trying to say.” The problem is that explanations like these often distract readers from the words of the poem, send them on a detour from experiencing the poem. Instead, lead your students to focus on what the poet is saying rather than what we think he or she is “trying to say.” An important thing to remember about theme in a work of literature is that it is how one person sees it. No theme should be taken as a moral certitude. Your students should feel free to disagree with how a poet sees the world.

“Autumn Movement” by Carl Sandburg (appendix D) Tasks Pre-reading Note that standard L5a (Students will identify and interpret the use of personification, alliteration and onomatopoeia in text) is a target standard for quarter 4 (reference Sixth Grade Language/Speaking & Listening Learning Targets 2014-15). Instruction for these examples of figurative language (as well as a review of those taught in previous grade levels) may be necessary during this week. As opposed to teaching figurative language in isolation, embed them as you teach the poems (this can be during your grade level planning).

Read “Autumn Movement” First Read: Have students read the poem “Autumn Movement” independently for the first reading. It’s okay for them to struggle with comprehension! Poetry is difficult but they need to be able to struggle through it. Have students focus on their initial reaction to the poem and

11 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

what they think it is about. In other words, what is the ‘gist’ of the poem? They can take notes and annotate as needed. o After the first read, have students discuss with a shoulder partner what their initial reaction is to the poem and why (which line leads them to think that way). Second Read: Have students read the poem a second time. Have students focus on the figurative language that is being used in the poem. (6th grade is not the first time they have seen figurative language). o After the second read, have students discuss with a partner the figurative language they found. Allow them time to discuss what they found. It is okay if they are wrong. They need the chance to work with the text. o Bring the class back together and discuss the figurative language. Allow students to provide their examples of the figurative language and at this time explain why the student may be accurate or inaccurate in their interpretation of the language. o Things to consider: Lines 2 and 3: The field of cornflower yellow is a scarf at the neck of the copper sunburned woman, the mother of the year, the taker of seeds. … What are they comparing the field to? Third Read: Have students read the poem a third time. Have students make notations on the text about what they understand (!) or what they are still confused about (?). Give them the following questions to think about prior to reading: What is does “the field of cornflower yellow” represent? (sunflowers? corn?) What is the copper woman, the mother of the year, the taker of seeds? (earth/mother earth). What does yellow is torn full of holes mean? (the plants dying because winter is coming). What do you think the new beautiful things are? (winter, snow). o After the third read, have students work with their partner in discussing the questions. Allow them to discuss what they know and what they are still struggling with. o Bring the class back together and discuss the questions whole group. It may be necessary to go line by line with the students: I cried over beautiful things knowing no beautiful thing lasts. (narrator is upset that change is coming even though they know that nothing lasts and change in inevitable.) The field of cornflower yellow is a scarf at the neck of the copper sunburned woman, the mother of the year, the taker of seeds. (The fields of corn is like a scarf on mother earth-copper sunburned woman, mother of the year, taker of seeds is earth ) The northwest wind comes and the yellow is torn full of holes (harvest season is over, the colder weather changes the field and plants) new beautiful things come in the first spit of snow on the northwest wind (the new things are winter- rain, snow) and the old things go, not one lasts. (the old things- Autumn, the plants)

Group Work Place students into groups of three or four. Give each student a TP-CASTT analysis protocol (appendix A). Have students work in their groups to complete each component of the protocol (either on notebook paper, chart paper, word processing, PowerPoint, etc.). Each student should complete/turn in/post their own work but the work is done collectively in the group.

“Nothing Gold can Stay” by Robert Frost (appendix D) Tasks Pre-Reading Discussion Questions: Write the title of the poem on the board and ask the students what they make of it as a title of a poem. What do they think it means? You might draw their attention to the apparent contradiction: doesn’t gold stay gold forever? How can it be that gold cannot/does not stay the same?

12 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Exploring Change-Small and Large group activities After students have suggested some possible explanations for the title, break the class into groups of three or four students and give each group a copy of the Change organizer (Appendix A??). Have them use it to map out some of their thoughts about cycles and change, which is the theme of Frost’s poem. When the groups have completed their organizers, ask them to give examples of things people do to avoid change. For example, to stay healthy, some people exercise, others take vitamins and supplements. Others choose to have cosmetic surgery in order to remain young looking. Do these practice stop change? Slow it down? Can you think of things that groups---families, teams, nations---do to avoid change?

Close Reading: Getting to Know the Poem Noticing Figurative Language: We can understand the theme of this short poem by examining its metaphors, especially in the first stanza, where Frost lays out one of his beliefs about life. The metaphors in this poem may be challenging for your more literal-minded students, but you can help them by looking at the stanza line by line and asking some leading questions Nature’s first green is gold. How can green be gold? (It helps if your students understand that gold is a symbol of something precious and valuable. Those first shoots and leaves symbolize rebirth and new life and are equally precious, and therefore gold.) Her hardest hue to hold. What is Frost saying here? (Frost is not speaking literally, of course. He means that the first green is the stage of growth that goes by the most quickly.) Her early leaf’s a flower;/But only so an hour. How do these two lines reinforce what Frost has stated in the title and the opening lines? (The quick passing of time, the impermanence of the fresh green shoots and leaves of spring…Again, only an hour isn’t literal; Frost is using hyperbole to make his point. The first stanza introduces the theme of this poem: things of life change very quickly. Frost continues in this vein in the second stanza with references to Eden ending sadly---it sank to grief—and every day passing quickly---So dawn goes down to day---and finally his repetition of the title in the final line---Nothing gold can stay. Continue questioning the students about the second stanza in the same way you did for the first stanza. For example: Then leaf subsides to leaf. What is Frost implying here? How do the first three lines connect? Then leaf subsides to leaf. So Eden sank to grief/ So dawn goes down to day. (So = likewise, or just as) What is the significance of repeating the title at the end of the poem?

Noticing Sound: Frost does a number of interesting things with sound in this poem. The students are likely to recognize that the poem is written in couplets—pairs of lines with end rhymes—with the rhyme scheme aabb ccdd. These end rhymes help hold the poem together. Also point out that the final couplet brings the poem to a firm conclusion. Have your students find the alliteration (repetition of the initial consonant sounds) that Frost uses: Line 1: green/gold Line 2: her/hardest/hue/hold, continued to line 3: her Line 7: dawn, down, day He also repeats other sounds skillfully: Line 3: er as in her early Line 4 o as in only so Line 7 o as in so/goes 13 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Say It Out Loud: Students can perform the poem as responses between 2 voices: Nature’s first green is gold, Her hardest hue to hold, Her early leaf’s a flower; But only so an hour. Then leaf subsides to leaf. So Eden sank to grief, So dawn goes down to day. Nothing gold can stay.

Events in the plot-partner work Ask students what the events of this poem are (ie; Fall-green is now gold, Trying to hold on to the leaves, but it doesn’t work, the leaves fall anyway—leading to winter. Spring is the early leaf’s blossoming as flowers, the late spring and the flowers die and only the green leaves are left---eventually leading back to the fall). Have students use the cyclic events graphic organizer with a partner and fill in the events as they see them happening in the poem. Using the cyclic event graphic organizer (Appendix A), students work in partners to write a summary without giving their opinions or feelings about it.

(Lesson adapted from: Janeczko, Paul B., Reading Poetry in the Middle Grades, Heinemann, Portsmouth, NH)

Exploring the theme Use some of the following questions in a class discussion to explore theme: What message is the poet trying to send or help you understand? Does it relate to your life in any way? What does the poem say to you? Using the “What it’s REALLY All About” graphic organizer students will either write their own suggestion for the theme of the poem, Nothing Gold Can Stay, or be provided with one from the teacher (possibilities: Life is such a fragile thing and most of it is taken for granted. The most precious time in life generally passes in what could be the blink of an eye. Change is eminent and will happen to all living things).

14 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Week 3: Nikki Giovanni Standards: Learning Targets: RI 1: Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well RI 1: Orally and in writing, students will cite several details and as inferences drawn from the text. examples to support not only what the text explicitly says but through RI 2: Determine a central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through particular drawing inferences. details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments. RI 2: Students will distinguish between objectivity and subjectivity in RI 3: Analyze in detail how a key individual, event, or idea is introduced, illustrated, the text as well as objectively summarizing the text. and elaborated in a text (e.g., through examples or anecdotes). RI 3: Orally and in writing, students will analyze, in detail, how RI 6: Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text and explain how it is individuals, events or ideas in a text are introduced and change over the conveyed in the text. course of the text. RI 7: Integrate information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, RI 6: Students will determine an author’s point of view in an quantitatively) as well as in words to develop a coherent understanding of a topic or informational text as well as how the author uses supporting details to issue. support that point of view. Orally and in writing, students will explain RI 9: Compare and contrast one author’s presentation of events with that of another how the point of view is conveyed in a text by evaluating what (e.g. a memoir written by and a biography on the same person.). information the author chooses to present, statements used within the W 2: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas, concepts, and text and the use of language. information through the selection, organization, and analysis of relevant content. RI 7: Given multiple sources of information, students will chart (2a,b,c,d,e,f) information from those sources to present a coherent understanding of a topic. Students will present their understanding both orally and in writing. RI 9: Students will compare how different authors portray the same idea or event. W 2: With the use of a graphic organizer, students will write a formal, informative multiple paragraph piece to examine a topic. Students will support the topic with important information and use various strategies to examine the information about the topic. Week 3 Teacher Background Knowledge/Key Information: Students will read two texts about the life of Nikki Giovanni. One is a biography and one is an interview. They will read and respond to these texts by making notes, underlining, highlighting and annotating the texts. Students may consult dictionaries and thesauruses if needed.

Nikki Rosa Biography (appendix D) Guided Reading Activity Text 1: The biography o Before reading the biography from www.nikki-giovanni.com/bio.shtml, instruct students to preview the text and then discuss any thoughts and questions they have about the text based on the features they noticed. o What predictions can they make about the text? o During the reading of the text, students will stop after every paragraph to take notes using a 3 column note-taking format. One column is for questions and predictions, the next section is for answers to the questions and confirmation of predictions, and the final column is for key ideas, interesting language and their feelings about what they read. Or, follow the directions for Critical Reading Strategies outlined in week one. o After reading the entire text, students will record any additional thoughts about the text on the back of the 3 column chart.

15 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Class Discussion

Nikki Rosa: Interview (appendix D) Text 2: The interview o Before reading the Nikki Giovanni Interview Transcript instruct students to preview the text and then discuss any thoughts and questions they have about the text based on the features they notice. How is the format of this text different from the format of the biography? o What predictions can they make about the text? o During the reading of the text, students will stop after each page to take notes using a 3 column note-taking format. One column is for questions and predictions, the next section is for answers to the questions and confirmation of predictions, and the final column is for key ideas, interesting language and anything else they find interesting. Or, follow the directions for Critical Reading Strategies outlined in week one. Comparing the texts o Next, students will consider any connections between the two texts using a Venn Diagram or the Compare/Contrast graphic organizer in Appendix A. o In small groups or partners students will answer the following questions: How are the biography and the interview alike? You may want to look at the ideas you wrote in the graphic organizer, your notes, and the texts. How are the biography and the interview different? You may want to look at the ideas you wrote in the graphic organizer, your notes, and the texts. What connections can you make between the 2 texts? In other words, what ideas come to you when you think about the similarities and differences between these 2 texts? Write your thoughts and ideas in a paragraph. Class Discussion Class Discussion: How do the biography and the interview provide insight into Nikki Giovanni? How is the information alike? Different? Why would the information be different when it was about the same person? Cite specific information from the texts to justify your response. Writing Choices QuIP Strategy (McLaughlin, E.M. (1987) The QuIP is a simple strategy to get students asking their own questions and writing about their findings. The graphic organizer is included in Appendix A. Students will first generate questions they have about Nikki Giovanni. Find the answers to their questions in both texts (they may need to do further research online) and write a brief summary of their findings in a paragraph or two. Compare/Contrast essay o Using the information from their graphic organizers, notes and the two texts, students will write a compare/contrast multiparagraph essay. The goal is to move students away from the obvious comparisons (one was written by an adult, the other was written by students, one was written in paragraph form, the other in a question/answer format) to more in depth work. Encourage students to address both the content and the mediums, their feelings and their thoughts when they read each text, and how and why each text emphasized different things about her life. Compare/Contrast organization 1. Whole-to-Whole, or Block In this structure, you say everything about one item then everything about the other. For instance, say everything about the 16 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

presentation and/or what the student experiences regarding the biography and then everything about the same for the memoir. Whole-to-Whole comparison and contrast uses a separate section or paragraph for each item you're discussing. The points in each of the sections should be the same and they should be explained in the same order. 2. Similarities-to-Differences In this structure, you explain all the similarities about the items being compared and then you explain all the differences. For instance, you might explain that the presentation and/or what the student experiences were similar in both the biography and memoir in the one section. In the next section, you could explain how the presentation and/or what the student experiences were different. Similarities-to-Differences comparison and contrast uses a separate section or paragraph for similarities and differences. In other words, the body of your paper would have two large sections: one for similarities, and another for differences. 3. Point-by-Point In this structure, you explain one point of comparison before moving to the next point. For instance, you would write about the presentation and/or the student experience regarding one piece of both the biography and the memoir in one section; then you would write about the presentation and/or the student’s experiences regarding another piece for both the biography and the memoir in another section. Point-by- Point comparison and contrast uses a separate section or paragraph for each point. For consistency, begin with the same item in each section of your point-by-point paper. Enrichment Opportunity Living Legend? Or Not? “…and over the course of more than three decades of publishing and lecturing she has come to be called both a “national Treasure” and, most recently, one of Oprah Winfrey’s twenty-five “Living Legends.” (http://nikki-giovanni.com/print_bio.shtml)

Do you agree or disagree that Nikki Giovanni is considered a “national Treasure” and one of twenty-five “Living Legends?”

Fill in the Persuasive Essay: Graphic Organizer to plan your essay.

State your claim (What is your opinion on this topic?) and then provide reasons and evidence that support your claim from the biography and interview texts.

Write (or type) your essay. Refer to your plan and the texts as you write. Don’t forget to note where you got your evidence from.

17 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Weeks 4: “Nikki-Rosa” Standards: Learning Targets: RL 1: Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly RL1: Orally and in writing, students will cite several details and examples of as well as inferences drawn from the text. textual evidence to support what the text explicitly says and by drawing RL 2: Determine a theme or central idea of a text and how it is conveyed inferences. through particular details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal RL2: Students will distinguish between objectivity and subjectivity when opinions or judgments. analyzing a text, consider literary elements as well as facts when RL 3: Describe how a particular story’s or drama’s plot unfolds in a series of determining the theme and provide an objective summary of the text. episodes as well as how the characters respond or change as the plot moves RL6: Students will distinguish between the author and narrator/speaker toward a resolution. in a text as well as identify the point of view of a narrator or speaker in a RL 6: Explain how an author develops the point of view of the narrator or text. speaker in a text. RL 7: Students will compare/contrast their experience when text is read RL 7: Compare and contrast the experience of reading a story, drama, or verses audio or video of the same text. poem to listening to or viewing an audio, video, or live version of the text, including contrasting what they “see” and “hear” when reading the text to what they perceive when they listen or watch. Week 4 Teacher Background Knowledge/Key Information: In her poem "Nikki-Rosa," Nikki Giovanni describes specific moments from her childhood. A close reading of a poem helps students go beyond identifying simple and obvious characteristics to explore the poet and in this poem, also the narrator, in more depth. In the case of this poem by Nikki Giovanni, for instance, students can move from "identify[ing] the speaker as black and from the country" to "think[ing] about what they can tell from the poem about [the speaker's] attitudes, about what they think might be [the speaker's] priorities in life." The images she recalls are more than biographical details; they are evidence to support her premise that growing up black doesn't always mean growing up in hardship. This is a link to resources about Nikki Giovanni, the poet: http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/calendar-activities/poet-nikki- giovanni-born-20729.html

“Nikki-Rosa” Tasks Pre-Reading Review Review types of figurative language: personification, metaphors, similes, onomatopoeia Review 1st person and 3rd person narration Review the difference between subjectivity and objectivity (1.Objective and subjective statements are used by speakers to get their points across. 2.Objective statements are facts that can be verified by third parties while subjective statements may or may not be entirely true as they are colored by the opinions of the speaker.) Read more: http://www.asdatoz.com/Documents/Website-%20Objective%20vs%20subjective%20ltr.pdf

Pre-Reading Discussion (“Nikki-Rosa” by Nikki Giovanni) What comes to your mind when you say or hear that someone has had a “hard childhood?” When you think about some of the things you have experienced as children, what might make some people feel sorry for you, but were actually pleasurable to you? (Students might recall having to share a bed with a sibling where there was plenty of squabbling over space but also many sweet secrets shared. Or a student might remember weekly chores like ironing her father’s shirts which, though she would never admit it to her mother, made her feel closer to her dad. Students might offer memories of hand-me-down clothes, errands to the store, or leftover dinners.) Create a cluster on the board of all the features of this condition from your students’ point of view. 18 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

First & Second Reading: Connecting personally with the poem Pass out copies of “Nikki-Rosa.” Ask students to read the poem independently and while they read to take notes on a T chart: What I visualized while I read---What I experienced (or felt, heard, remembered, connected to, wondered about…) while I read. Next they should discuss their T chart findings with a small group of peers. Play the video of Giovanni reading her poem “Nikki-Rosa” for students (the video loads automatically, but you need to click the play arrow to start the video). http://nikki-giovanni.com/nikkirosa.shtml Because of the small size of the image you may want to structure small groups of students, gathered around a single computer if projection equipment is not available. First, allow them to watch and listen without taking notes. Then allow them to watch and listen again while they reflect, using the same type of T chart (What I visualized while I listened and watched--- What I experienced (or felt, heard, remembered, connected to, wondered about…) while I listened and watched. Next they should discuss their T chart findings with a small group of peers. Hold a whole class discussion comparing and contrasting the experience of reading the poem independently to listening to and viewing the video of the text. Then discuss any connections they can make to what they read about Nikki Giovanni last week.

Third Reading: From the author’s point of view Finally, have them read the poem a third time, underlining or highlighting all the words and phrases that describe the various pleasures the speaker in the poem remembers experiencing in her “hard” childhood. Remind students that while this poem may seem to be obviously autobiographical-the title is reasonably strong evidence-a careful reader always considers the speaker in a poem to be separate from the author. Initiate a discussion of the poem. The questions below can be starters for the discussion, but encourage the conversation to roam where it will. Requiring students to answer a list of questions could make them hate the poem forever. o Did any of the phrases that you marked in “Nikki-Rosa” remind you of your own childhood experiences? Cite these phrases and tell how that made you feel about what you read. o How would you describe the speaker’s attitude toward her childhood? Cite evidence directly from the text to support your answer. Why do you think that she is worried that a biographer will “never understand”? o What do you think you “understand” about the circumstances of the speaker’s childhood? Cite the text as you speak. (Push students to be very specific here in order to help them recreate the world in which these childhood remembrances existed.) o Why do you think Nikki Giovanni chooses to address the reader directly as “you”? What effect did this have on you as a reader? What assumption does this use of the second person make about Giovanni’s expectation of who her readers will be? o How did you interpret the line “And though you’re poor it isn’t poverty that / concerns you”? If it wasn’t poverty that concerned the speaker, what was it that concerned her? o Note that the line “and I really hope no white person ever has cause / to write about me / because they never understand” might cause some students to feel that Giovanni is casting them as the “bad guys” in the poem. Encourage students to think about how Giovanni’s experience as a black person might lead her to make this generalization about white people. Discourage students from relegating such generalizations to the “bad old days” before the Civil Rights movement. If the issue comes up, it is important to discuss the pervasive presence of racism in our own society and how this shapes our generalizations about who we expect will “understand” us and who we expect never will.

Summarize 19 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Write a summary of the poem in your own words.

(This lesson was adapted from the readwritethink.org lesson plan by Traci Gardner, Childhood Remembrances: Life and Art Intersect in Nikki Giovanni’s “Nikki-Rosa.”)

Small Group Work After reading and discussing “Nikki-Rosa” what is the most important idea that Giovanni is trying to express about her childhood? Work cooperatively with a small group of students to find quotes that reveal Giovanni’s thoughts and feelings about her childhood. Justify your choice. Use the worksheet “Quote Me.” (Appendix A). Meet as a whole class to discuss the quotes and justifications from the small group work done on “Quote Me.”

Interpreting the Theme Using the “What it’s REALLY All About” graphic organizer (Appendix A) students will either write their own suggestion for the theme of the poem, Nikki Rosa, or be provided with one from the teacher (you might consider: money doesn’t equal happiness, happiness is in the eye of the beholder, family and community bonds create “wealth”, you must wear my shoes to understand my life, adversity is a state of mind rather than a set of circumstances).

CFA Use the poem, speak up, by jamaya ewing (see appendix D). Students can do the following activities independently. After reading the poem, have students find the 3 quotes that they feel best express the importance of speaking up. Use the “Quote Me” worksheet to write their quotes and to justify their thoughts. (RL 6.1) Using the :What it’s REALLY All About” graphic organizer students will either write their own suggestion for the theme of the poem, “speak up,” or be provided with one from the teacher (you might consider: life is too short to hide who you really are, your own unique expression must be heard, be courageous enough to be yourself)

20 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Week 5: “Vincent” Standards: Learning Targets: RL 1: Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly RL1: Orally and in writing, students will cite several details and examples of as well as inferences drawn from the text. textual evidence to support what the text explicitly says and by drawing RL 7: Compare and contrast the experience of reading a story, drama, or inferences. poem to listening to or viewing an audio, video, or live version of the text, RL 7: Students will compare/contrast their experience when text is read including contrasting what they “see” and “hear” when reading the text to what verses audio or video of the same text. they perceive when they listen or watch. W 2: With the use of a graphic organizer, students will write a formal, W 2: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas, informative multiple paragraph piece to examine a topic. Students will concepts, and information through the selection, organization, and analysis of support the topic with important information and use various strategies relevant content. (2a,b,c,d,e,f) to examine the information about the topic. Week 5 Teacher Background Knowledge/Key Information: This week students will be focusing on the poem “Vincent” by Tim Burton. Students will read a biography about Tim Burton to build background knowledge and then do a close read of the poem. It is important to give students time to work in collaborative groupings. Students will also view the poem “Vincent” as it is read and illustrated in a video. If you do not have immediate access to technology in your classroom, please make arrangements to watch it in another classroom/computer lab that had technology available. Students will then be required to write a short compare/contrast (4 paragraph) paper on the presentation/experience of the reading the poem and watching the video.

Tasks Building Background Ask students if they know Tim Burton? Do they know of his movies? Chart on the board or chart paper their responses. Read “Tim Burton: Biography” (appendix D). This text is meant to give the students an idea of who Tim Burton is but they will not be expected to do a close read on the text. Discussion Questions o Have any of you seen one or more of the movies listed in the biography? What are his movies like? o What types of films did Burton like to watch as a child? (horror films) How do you think this influenced his film making later in life? o Who was Vincent Price? (Reference text). Explain that famed actor Vincent Price played a key role in Burton’s upbringing.

“Vincent” (poem) Read “Vincent” by Tim Burton First Read: Have students read the poem “Vincent” independently for the first reading. It’s okay for them to struggle with comprehension. Have students focus on their initial reaction to the poem and what they think it is about. In other words, what is the ‘gist’ of the poem? They can take notes and annotate as needed. After the first read, have students discuss with a shoulder partner what their initial reaction is to the poem and why (which line leads them to think that way).

Second Read: Have students read the poem a second time. Have students focus on the vocabulary that is difficult. Although this should not be a difficult read for most, words like ghoulish, gruesome, portrait, encased, tomb and possessed may be difficult specifically with ELs. After the second read, chart the words that students do not know on the board or chart paper. After the second read, discuss how the author uses vocabulary in the poem.

21 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

What do students imagine or ‘see’ when they read the poem? How does the vocabulary influence those images in their mind? What text structures the poem for the ease of reading? (rhyming, short sentences, use of adjectives, dialogue, etc.).

Third Read: Have students look deeper into the poem and the meaning. Students will read the poem a third time and being to take the poem apart. o Some examples of things to point out if the students are not able to do it: o Line 8: And wander dark hallways, alone and tormented (wanders- does not have a purpose to be there, tormented- he is a pain) o Lines 14 and 15: Could go searching for victims in the London fog; His thoughts, though, aren’t only of ghoulish crimes (what is he thinking about? Hurting others- victims would be his victims- he is thinking of committing a ghoulish crime) o Line 29: While alone and insane encased in his tomb (Where is he actually? Where is he pretending to be?) o Line 36: “I am possessed by this house, and can never leave it again” o Lines 45-46: The room started to swell, to shiver and creak; His horrid insanity had reached its peak o Lines 51-52: Every horror in his life that had crept through his dreams; Swept his mad laughter to terrified screams! Discussion Questions Who is the character trying to be like? (Line 4). How is this significant to the author Tim Burton? (refer back to his biography which stated he grew up watching horror movies and his favorite actor Vincent Price). Reread the first four lines of the poem. What do we learn about the boy Vincent in these first four lines? What technique does the author use to tell Vincent’s story and show what Vincent is thinking? (He weaves reality and imagination together throughout the text). What are some examples of this technique? (this can be turned into a group task where students together identify the examples) How do you know that Vincent is imagining a different life? (Student identify the lines: example- line 22 talks about his beautiful wife being dead but he is only seven years old, he doesn’t have a wife).

Graphic Organizer o Have students complete the “poem” side of the graphic organizer Compare and Contrast: Poem/Video(appendix A) Save to use later

Group Task o Place students into groups of three or four. Give each student a TP-CASTT analysis protocol (appendix A). Have students work in their groups to complete each component of the protocol (either on notebook paper, chart paper, word processing, PowerPoint, etc.). Each student should complete/turn in/post their own work but the work is done collectively in the group.

“Vincent” (video) Watch the short video of “Vincent” being read by Vincent Price http://shortsbay.com/film/vincent https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BIS04fIoUGA IF neither of these links work, please log in to your active directory and go to www.youtube.com. Search “Vincent by Tim Burton” and a list of options will become available for you to choose. Discussion 22 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

o Allow students to talk with a partner about their first experience watching the video. The following questions can be answered whole group, with a partner or in a small group: . How do the sound effects enhance the poem? . How do the visual images enhance the poem? . Why do you think the video is in black and white? . What technique does the video use to show the difference between what is real and what Vincent imagines? (real time the video is lighter, music is usually happier, Vincent’s hair is ‘normal’ but during the imaginary time, the music is scarier, the images darker, hair is messy). . Does the video match what you imagined? . How does the voice of Vincent Price reading the poem make you feel? . Why do you think Tim Burton wanted/had Vincent Price read the poem? What is the significance?

Graphic Organizer o Have students complete the “video” side of the graphic organizer they worked on previously. (Titled: Compare and Contrast: Poem/Video(appendix A)).

Writing o Students are going to write a short compare and contrast paper based on the poem “Vincent”. Explain to students that they are comparing and contrasting how the poem was presented and their experience with both in each format. During the reading of the poem, students had to rely on the words and descriptions to conjure images of what the poem was about. For the video, the music, sound and lighting effects played a role in the students understanding of the poem as well as the voice of the narrator. Remind students that they aren’t comparing and contrasting the events or plot of the poem and video because that is the same but more the presentation and their experiences of the poem in the two differing formats. o Remind students that as they begin to organize their writing, it's important to make sure that they balance the information about the items that they're comparing and contrasting. They will need to be sure to give both items equal time in what they write. o There are three strategies to organize comparison and contrast papers: 1. Whole-to-Whole, or Block o In this structure, you say everything about one item then everything about the other. For instance, say everything about the presentation and/or what the student experiences regarding the characters, setting, structure and/or plot for the read poem and then everything about the same for the video. Whole-to-Whole comparison and contrast uses a separate section or paragraph for each item you're discussing. The points in each of the sections should be the same and they should be explained in the same order (for instance, you might discuss the presentation of the character, setting, and plot for both, and in that order for both). 2. Similarities-to-Differences o In this structure, you explain all the similarities about the items being compared and then you explain all the differences. For instance, you might explain that the presentation and/or what the student experiences regarding the characters and plot were similar in both the poem and video in the one section. In the next section, you could explain that the presentation and/or what the student experiences regarding the characters and the plot were different. Similarities-to-Differences comparison and contrast uses a separate section or paragraph for similarities and differences. In other words, the body of your paper would have two large sections: one for similarities, and another for differences. 23 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

3. Point-by-Point o In this structure, you explain one point of comparison before moving to the next point. For instance, you would write about the presentation and/or the student experiences regarding the characters in the poem and video in one section; then you would write about the presentation and/or the student’s experiences regarding the setting in the poem and video in the next section. Point-by-Point comparison and contrast uses a separate section or paragraph for each point. For consistency, begin with the same item in each section of your point-by-point paper. For instance, for each point that you discuss, explain the information about the poem first and then about the video. o Students will begin writing their compare/contrast paper. It should be at least four paragraphs long with short introductory/conclusion paragraphs and two paragraphs for the body.

24 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Week 6: Sandra Cisneros Standards: Learning Targets: RI 9: Compare and contrast one author’s presentation of events with that of another RI 9: Compare and contrast one author’s presentation of events with (e.g., a memoir written by and a biography on the same person). that of another (e.g., a memoir written by and a biography on the same W 2: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine a topic and convey ideas, concepts, and person). information through the selection, organization, and analysis of relevant content. W 2: With the use of a graphic organizer, students will write a formal, (2a,b,c,d,e,f) informative multiple paragraph piece to examine a topic. Students will support the topic with important information and use various strategies to examine the information about the topic.

Week 6: Teacher Background Knowledge/Key: This week students will read a memoir by Sandra Cisneros and a biography about her. Students will compare and contrast the information they learn about Sandra Cisneros in both the memoir and the biography. It is important to explain to students the differences between a memoir and a biography and explain that as they read the text their role as a reader is different and therefore the information they may learn and what they learn will be different. The week will conclude with a short, four paragraph writing task in which the students will compare and contrast the author’s presentation of information in the biography and the memoir.

Sandra Cisneros: Biography Tasks Reading a biography: Provide instruction on the definition and characteristics of a biography. Ask students what they think of when they hear the word biography. Chart answers on board. Explain that a biography is a narrative nonfiction/historical nonfiction which presents the facts about an individual's life and makes an attempt to interpret those facts, explaining the person's feelings and motivations. Explain that good biographers (authors of biographies) use many research tools to gather and synthesize information about their subject, including the person’s words, actions, journals, reactions, related books, interviews with friends, relatives, associates and enemies, historical context, psychology, primary source documents. Explain that the purpose of a biography is often to understand the person and the events and history affected by that person. It is important to note that biographers possess a point of view, a larger agenda and/or a purpose in reporting and writing on the person’s life. Explain that a biography has a number of characteristics including: o often starts with birth or early life and often covers birth-to-death o often delves in to a person's formative years, exploring early influences on a subject's later life o situates person’s life in historical terms and a cultural context o uses direct quotes from person and those who knew her o sometimes uses fictionalized scenes/dialogues but always based on what is known about the person and the events described, o often uses pictures, maps, photographs, or other historically available documents. The role of the reader: Explain that as a reader of a biography, one should consider author’s purpose in presenting the biography. Is it idealized? fair? Why or why not? Who is the biographer? When was this biography written? How does this affect my reading of it? How does this help me to understand the influence of this person on history, and history and culture’s effect on her? How might this person be a model for things to do or not do in my own life?

25 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6

Read: Sandra Cisneros: Biography (appendix D) Close Reading of Sandra Cisneros: Biography o When doing a close read on a biography, First Read: Explain to students the purpose for reading the biography is to gain knowledge about the life and career of Sandra Cisneros. Have students read text as independently as possible. Depending on the text complexity and the readers, the first read may be done independently, as a read aloud/think aloud, or paired or shared reading. The first read should be without building background; students should be integrating their background knowledge with the text as they read. Focus on the key ideas and details in the text, making sure that readers know the main idea, story elements, or key details that the author includes. What’s the gist of the biography? As they identify the main idea and details tell them to think about what type of information is being provided in the biography. They may mark/annotate the text as needed. o After the first read, have students discuss (with a shoulder partner) the key ideas and details they learned about Sandra Cisneros. Have them discuss the type of information: Personal? Professional? Feelings? If they are Cisneros feelings, how does the text explain her feelings? (ex- quotes). Etc. Second Read: Students read the biography a second time. Have them underline words or phrases that they are unfamiliar with or need clarification. o After the second read, have the students discuss (with a shoulder partner) the vocabulary- words and phrases that they found confusing or unfamiliar. Let the pairs discuss what they found confusing and give them an opportunity to help each other with comprehension. o As a whole class, go back to the text and ask the students what they are struggling with and clarify information they are struggling with. Third Read: Have students read the biography a third time. Tell the students to think about the following questions as they read: What childhood experiences helped shape Cisneros writing career? What does Cisneros mean when she said that at school she learned “what I didn’t want to be, how I didn’t want to write.”? How does the structure of the text (events are in chronological order) help you understand her life and career? What might be missing (lead the students to understand that this biography covers her entire life on one page and it gives key events in her life but doesn’t tell the whole story)- is this biography her entire life story or just the important parts? Who decided on the important parts? (author). This would be a good place to explain that the author of the biography plays a key role in deciding what information is included and what information is not. o Have students answer the following questions with their shoulder partners after they are done reading for the third time. After they have answered and discussed these questions with their partners, bring the class back together and discuss whole group.

Graphic Organizer o With a partner or in groups, have students complete the Biography/Memoir Graphic Organizer (appendix A). Students should be able to work independently if the close reading was done prior and discussions were supported after each read.

“Only Daughter” by Sandra Cisneros Tasks Reading a memoir: Provide instruction on the definition and characteristics of a memoir. Ask students what they think of when they hear the word memoir. Chart answers on the board. If they don’t say memory, direct them to that example. Explain that a memoir is a personal narrative that focuses on a specific period in the author’s life and describes in some detail the persons, 26 Language Arts Unit: Changes Timeframe: 8 weeks Grade: 6