In Pursuit of the Perfect Brainstorm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Pursuit of the Perfect Brainstorm - N…

1/6/2011 In Pursuit of the Perfect Brainstorm - N… Reprints This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. You can order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers here or use the "Reprints" tool that appears next to any article. Visit www.nytreprints.com for samples and additional information. Order a reprint of this article now. December 16, 2010 In Pursuit of the Perfect Brainstorm By DAVID SEGAL Last month, in a small room on the fifth floor of a high-rise building in San Mateo, Calif., three men sat around a table, thinking. The place was wallpapered with Post-it notes, in a riot of colors, plus column after column of index cards pinned to foam boards. Some of the cards had phrases like “space maximizers” or “stuff trackers” written on them. Many had little three- dimensional ink drawings and titles, like “color-coded Tupperware horizontal stacker.” It looked as if these guys had been locked in and told they couldn’t leave until they dreamed up 1,000 of the wackiest home-storage items they could imagine. Which was pretty much what happened. “We’re in our third month,” said one of the men, Clynton Taylor, “so we’re at about the halfway point.” This was a project room at Jump Associates, a company with 50 employees that comes up with ideas to solve what it calls “highly ambiguous problems.” Exactly what problem was being solved in the room, and which client asked Jump to solve it, the company wouldn’t say. -

USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis…

5/4/2010 USCIS - H-1B Approved Petitioners Fis… H-1B Approved Petitioners Fiscal Year 2009 The file below is a list of petitioners who received an approval in fiscal year 2009 (October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2009) of Form I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker, requesting initial H- 1B status for the beneficiary, regardless of when the petition was filed with USCIS. Please note that approximately 3,000 initial H- 1B petitions are not accounted for on this list due to missing petitioner tax ID numbers. Related Files H-1B Approved Petitioners FY 2009 (1KB CSV) Last updated:01/22/2010 AILA InfoNet Doc. No. 10042060. (Posted 04/20/10) uscis.gov/…/menuitem.5af9bb95919f3… 1/1 5/4/2010 http://www.uscis.gov/USCIS/Resource… NUMBER OF H-1B PETITIONS APPROVED BY USCIS IN FY 2009 FOR INITIAL BENEFICIARIES, EMPLOYER,INITIAL BENEFICIARIES WIPRO LIMITED,"1,964" MICROSOFT CORP,"1,318" INTEL CORP,723 IBM INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED,695 PATNI AMERICAS INC,609 LARSEN & TOUBRO INFOTECH LIMITED,602 ERNST & YOUNG LLP,481 INFOSYS TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED,440 UST GLOBAL INC,344 DELOITTE CONSULTING LLP,328 QUALCOMM INCORPORATED,320 CISCO SYSTEMS INC,308 ACCENTURE TECHNOLOGY SOLUTIONS,287 KPMG LLP,287 ORACLE USA INC,272 POLARIS SOFTWARE LAB INDIA LTD,254 RITE AID CORPORATION,240 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO,236 DELOITTE & TOUCHE LLP,235 COGNIZANT TECH SOLUTIONS US CORP,233 MPHASIS CORPORATION,229 SATYAM COMPUTER SERVICES LIMITED,219 BLOOMBERG,217 MOTOROLA INC,213 GOOGLE INC,211 BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCH SYSTEM,187 UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND,185 UNIV OF MICHIGAN,183 YAHOO INC,183 -

2007-2008 IDSA Annual Report

2007-2008 IDSA Annual Report “ ...there is no mistaking the importance of last year’s conference as a launching pad for the immediate past, the present still forming and the near future.” – Michelle Berryman, IDSA President A lifetime often passes before us in far smaller increments of time than we might expect. Looking back at the last 12 months of IDSA activity, our Society appears to have filled at least one lifetime. Maybe even more. We begin, of course, at the cusp of CONNECTING’07, “the design event of a life- time.” In assessing its short- and long-term takeaways, the story of these last 12 months—and the narrative looming for the next 12—begins to unfold. While some IDSA connections existed long before CONNECTING’07 stormed the streets of San Francisco and others developed independent of it, there is no mistaking the importance of last year’s conference as a launching pad for the immediate past, the present still forming and the near future. For one, the world had an opportunity to meet the Society’s then-new Executive Director, Frank Tyneski, IDSA. In his first year on the job, Frank has toured the world on behalf of IDSA, energizing members and nonmembers alike with a new vibrancy while furthering our core purpose of advancing the profession of industrial design through education, information, community and advocacy. He has not op- erated alone in that pursuit, though. In this annual report, we’ll trace the work that IDSA’s Board, staff and international community of volunteers and sponsors have completed to support our mission during the last 12 months. -

Jump Factsheet

It’s About Growth. Jump is one of the world’s leading strategy and innovation firms. We help create new businesses and reinvent existing ones. We use a hybrid approach, combining business strategy, social science and design. For nearly twenty years, we’ve worked with the world’s most admired companies to grow their businesses in times of change. OFFICES STAFF SELECT CLIENTS Jump California Jump has 50 associates, give or 3M 101 South Ellsworth, Suite 600 take. Jumpsters are differentiated by AARP San Mateo, California 94401 their hybrid backgrounds. A typical Aetna phone +1 650 373 7200 Jumpster has education and Audi experience in business strategy, Chrysler Jump New York design, as well as social science. FedEx 157 Columbus Avenue, 4th Floor Gannett New York, New York 10023 HISTORY General Electric phone +1 212 244 4991 Jump was founded in 1998. We General Motors created Jump to solve a new class of General Services Adminstration CONTACT problem. Management consultants Girl Scouts of America email [email protected] focused on strategy, design firms Grameen web www.jumpassociates.com created new products, yet no one Hewlett Packard twitter @jumpassociates worked in the space where you need Jamba Juice the qualities of both. Kaiser Permanente CERTIFICATIONS Mars Jump Associates LLC is a privately PURPOSE Merck held limited liability company Jump exists to transform lives NBC Universal organized under the laws of the through learning and growth. We’d Nike State of California. be delighted to have a conversation PepsiCo with you about why that’s critical to Procter & Gamble Jump is an approved contractor with business today. -

YEAR ONE MONDAY, MARCH 5, 2018 SUNDAY, MARCH 4, 2018 7:15 A.M

SECURITIES INDUSTRY INSTITUTE® PROGRAM YEAR ONE MONDAY, MARCH 5, 2018 SUNDAY, MARCH 4, 2018 7:15 a.m. – 8:15 a.m. BREAKFAST 12:00 p.m. – 5:00 p.m. (6:00 pm at the Marriott) REGISTRATION FOR ALL PARTICIPANTS 8:45 a.m. – 10:15 a.m. 5:00 p.m. – 5:30 p.m. WELCOMING REMARKS YEAR ONE ORIENTATION Vinny Ferrari Chair *Advance sign up required. Securities Industry Institute® Board of Trustees Please join the Securities Industry Institute® THE HOPE CIRCUIT Board of Trustees and all Year One participants for an orientation to kick off Institute Week. Martin Seligman, Ph.D. Zellerbach Family Professor of Psychology 5:30 p.m. – 6:15 p.m. Founding Director, Positive Psychology Center WELCOME RECEPTION University of Pennsylvania When Martin E. P. Seligman first encountered psychology *Advance sign up required. in the 1960s, the field was devoted to eliminating misery: it was the science of how past trauma creates present NETWORKING RECEPTION OPEN TO ALL PARTICIPANTS symptoms. Today, thanks in large part to Seligman’s Positive Psychology movement, it is ever more focused 6:15 p.m. – 8:00 p.m. not on what cripples life, but on what makes life worth living–with profound consequences for our mental health. OPENING NIGHT DINNER In this session Dr. Seligman will discuss learned *Advance sign up required. helplessness, positive psychology, and prospection in the light of building hope. YEAR UP Gerald Chertavian 10:35 a.m. – 12:05 p.m. CEO ETHICS – WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE Year Up ETHICAL? In the future, every young adult will be able to reach their Peter Conti-Brown, Ph.D. -

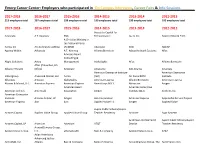

Employers Who Participated in on Campus Interviews, Career Fairs & Info Sessions

Emory Career Center: Employers who participated in On Campus Interviews, Career Fairs & Info Sessions 2017-2018 2016-2017 2015-2016 2014-2015 2013-2014 2012-2013 213 employers total 207 employers total 198 employers total 190 employers total 190 employers total 192 employers total 2017-2018 2016-2017 2015-2016 2014-2015 2013-2014 2012-2013 Access to Capital for Advocate A.T. Kearney 360i Entrepreneurs [x+1], Inc. Abercrombie & Fitch A Christian Ministry in the National Parks Aetna, Inc. Acuity Brands Lighting (ACMNP) Advocate 360i ADCAP Agency Within Advocate A.T. Kearney AllianceBernstein Adcap Network Systems Aflac Advisory Board Consulting & Alight Solutions Aetna Management AlphaSights Aflac AllianceBernstein Aflac (Columbus, GA Alliance Theatre Office) Advocate Altisource AGI Atlanta Allscripts American Enterprise Institute American Enterprise alliantgroup Alvarez & Marsal, LLC Aetna (AEI) Air Force ROTC Institute Allscripts Amazon AlphaSights American Express AllianceBernstein American Express Alvarez & Marsal, LLC American Express American Express AmeriCorps NCCC Altisource Amgen American Heart American Enterprise American Airlines Americold Association Amgen Institute (AEI) Anthem, Inc. American Enterprise Institute Antares Capital, LP Amgen Aon Corporation American Express Appalachia Service Project American Express Aon Aon Applied Value LLC Amgen Applied Value Aspire Public Schools/Aspire Antares Capital Applied Value Group Applied Value Group Teacher Residency Andover Argo Systems Andrews Entertainment Aspire Public Schools/Aspire Antares Capital, LP Arcesium Arcesium AT&T District Teacher Residency AroundCampus Group, Applied Value Group LLC athenahealth Bain & Company Applied Value Group AT&T Asian Americans Advancing Justice - ArchieMD, Inc. Atlanta Bain & Company Bank of America AroundCampus Group, The AutoTrader.com Atlanta Falcons - AMB AT&T Sports + Entertainment Bank of America BBVA Compass Aspire Public Schools Bain & Company Bard Globalization and Atlanta Network International Affairs Technologies, Inc. -

Crafting an Innovation Strategy

How does a firm reliably innovate time and again? Choosing those approaches that play to your company’s strengths can be the difference between success and failure. Crafting an Innovation Strategy By Dev Patnaik and Colleen Murray A hunger for internal growth has made billion company. An 8% organic growth rate innovation a critical mandate for top for GE would amount to generating $13 billion executives. As a result, many companies have in the first year alone – equivalent to creating a turned to an emerging group of innovation brand the size of Nike every year. Put in terms methodologies. Still highly varied in approach of another popular innovation, GE aimed to and reliability, these toolsets fuse right- and create the equivalent of what was at the time left-brain thinking, often drawing upon four new iPod businesses every year. Clearly, methods from anthropological research, turning GE into an innovation leader is no industrial design and business planning. The easy task. Moreover, it points to the real idea is that if companies discover unmet challenge for business leaders looking to drive customer needs, they can then develop clever new growth on an ongoing basis. Sponsoring and compelling new offerings to help drive one, two, or even several innovation projects growth. Indeed, many of these approaches do probably won’t satisfy the appetite of a large seem to yield repeatable results. Yet most of company. The problem is just too big. What’s their successes involve an individual product needed is a systemic approach to identifying or project. Promising though they might be, and developing new opportunities that can be it’s unclear how these tightly focused scaled across a large organization.