Bringing Order to Chemical Chaos

Imagine what nursing would be like if the FDA did not regulate drugs. There would be no requirement for pre-market testing. There would be no mandate to determine drug efficacy. We would not know about potential side effects (toxicity) or drug interactions. We wouldn’t have recommended doses and administrations. And without labeling requirements and “inserts”, consumers could not make informed decisions about the drugs they take. It would be chaotic and dangerous. It would be scary.

Welcome to the reality of chemical safety in the U.S.

In the world of chemicals and chemical products (that are non-pharmaceuticals) there is no requirement for pre-market testing for human health risks. We do not know the human health threats posed by the vast majority of chemicals for which we have daily exposures through our air, water, food, and household and personal care products because the research has not been done. We have virtually no idea about the interactions that may occur when we are exposed to two or more products and/or environmental pollutants, i.e. lead in our drinking water and mercury consumed in fish; herbicides that are used on our lawns and pesticide residues on our fruits and vegetables; and so on. Labels on the myriad of household and personal care products are totally insufficient to inform us about potential acute and chronic health effects (including possible carcinogenicity).

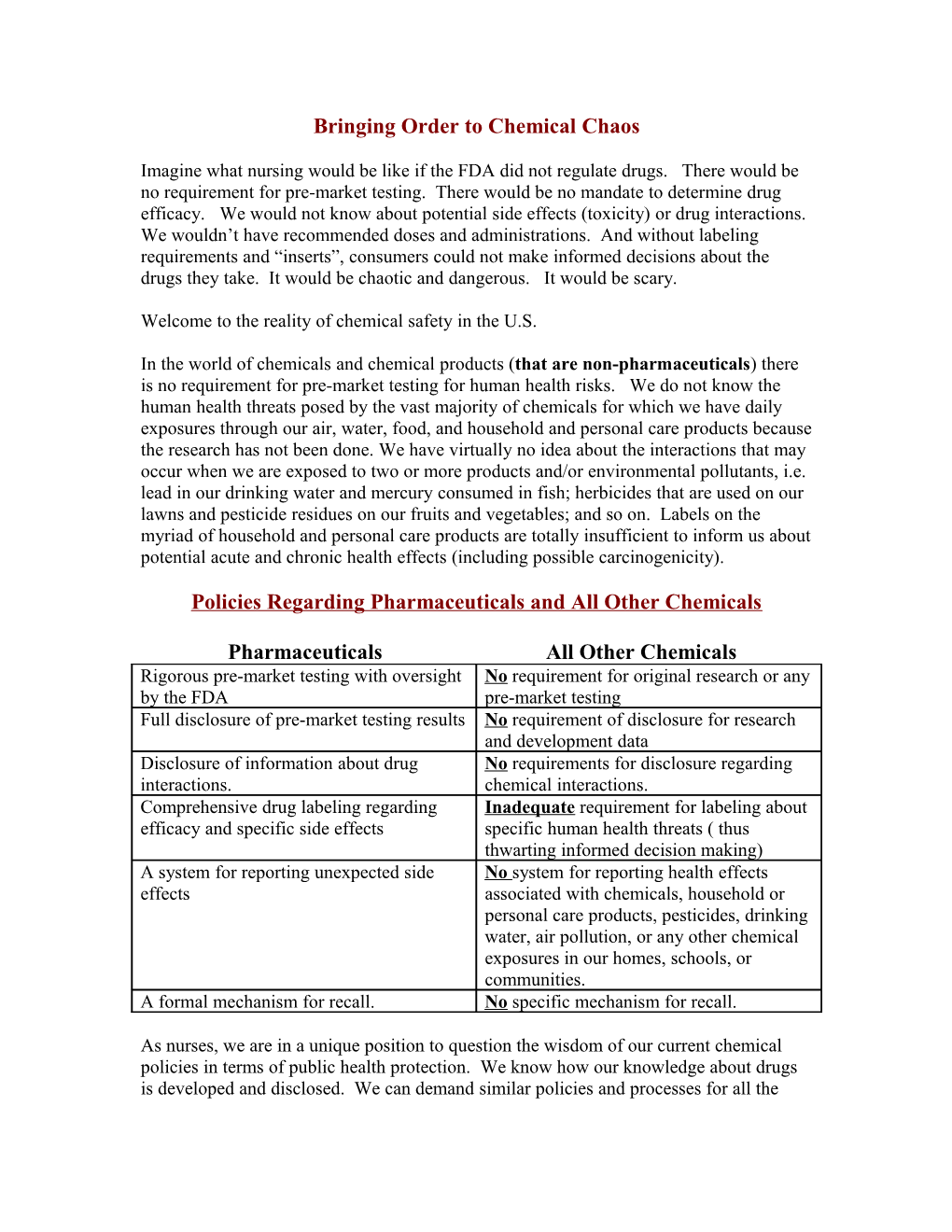

Policies Regarding Pharmaceuticals and All Other Chemicals

Pharmaceuticals All Other Chemicals Rigorous pre-market testing with oversight No requirement for original research or any by the FDA pre-market testing Full disclosure of pre-market testing results No requirement of disclosure for research and development data Disclosure of information about drug No requirements for disclosure regarding interactions. chemical interactions. Comprehensive drug labeling regarding Inadequate requirement for labeling about efficacy and specific side effects specific human health threats ( thus thwarting informed decision making) A system for reporting unexpected side No system for reporting health effects effects associated with chemicals, household or personal care products, pesticides, drinking water, air pollution, or any other chemical exposures in our homes, schools, or communities. A formal mechanism for recall. No specific mechanism for recall.

As nurses, we are in a unique position to question the wisdom of our current chemical policies in terms of public health protection. We know how our knowledge about drugs is developed and disclosed. We can demand similar policies and processes for all the products that we use and the pollution to which we are all exposed. So where do we start?

Last year, ten state nurses associations organized Environmental Health Task Forces. Another ten will be developed in the coming year. These Task Forces are helping to raise awareness about the critical relationship between health and the environment. They are looking at key environmental concerns within their respective states and determining the best ways in which to help improve the quality of our air, water, food, and products. Often the issues that are raised are inextricably tied to our failed chemical policies. In at least four states, discussions are focusing on the development of statewide legislative initiatives to improve chemical policies.

In Washington State, the state nurses association is playing a vital role in a coalition that is calling for a statewide phase-out of a particularly troubling category of chemicals - polybrominated diphenyl ethers. (See Box below)

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) are a group of chemicals that are widely used as flame retardants in products such as mattresses, furniture, electronics, plastics, automobiles, computers, and other products.

They persist in the environment, build up in animals and people, and are toxic.

At very low levels PBDEs impair memory, learning, and behavior in laboratory animals. They also affect thyroid hormones and other bodily functions. Most at risk are developing fetuses, infants, and young children.

There is strong scientific evidence that levels of PBDEs are rising rapidly in the environment and in human bodies, particularly in North America where the use of PBDEs is the highest.

Recent studies show that women in the United States have levels of PBDEs in their breast milk that are up to 100 times higher than the levels found in European women.

Studies in wildlife have shown that PBDE levels are rising at alarming rates, doubling every one to five years. In the Columbia River system, levels of PBDEs in fish doubled in a mere 1.6 years.

(Washington Toxics Coalition, 2006)

In Maryland, nurses were highly visible in the state capital as they successfully helped to pass a 2006 Clean Air Act that will reduce mercury and green house gases from being emitted into the air. They worked in collaboration with public health professionals, environmentalists, and concerned citizens to persuade legislators and the Governor about the importance of environmental protection as a health protection strategy.

In addition to the state Environmental Health Task Forces, nurses are organizing around environmental health issues in a variety of ways – big and small – all of which are helping to raise awareness about the relationship between the environment and human health. In a New Jersey hospital, nurses influenced the selection of floor cleaning products so that less harsh (but equally effective) cleaners were purchased. In a Boston neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), the nurses helped to change the purchasing policies so that the plastic tubing is free of the potentially harmful chemical DEHP. (See www.noharm.org for more information about DEHP).

This spring a new report will be released about nurses’ chemical exposures at work. On a national web-based survey, nurses reported the chemicals that they commonly work with and also reported the types of health problems that they experience. Look for this report to be released during National Nurses Week, May 6 - 12th. This collaborative project is part of an initiative by the American Nurses Association, the Nurses’ Work Group of Health Care Without Harm, and the University of Maryland School of Nursing to raise awareness about the chemicals that nurses work with and their potential health effects. Through these efforts we hope to engage nurses in a national dialog about the broader issue of chemical safety in our country.

There is already a robust conversation occurring among our friends and colleagues in the environmentalist community and nurses are joining in. Two new frameworks for thinking about chemical safety have been developed. In May 2004, Louisville hosted a meeting of groups (including Health Care Without Harm) and individuals whose common goal is to work together on campaigns that protect human health and the environment from exposures to unnecessary harmful chemicals. Through a consensus- building process, a set of guiding principles was created and named after the meeting city. (See: the Louisville Charter below)

The Louisville Charter for Safer Chemicals

A Platform for Creating a Safe and Healthy Environment through Innovation Fundamental reform to current chemical laws is necessary to protect children, workers, communities, and the environment. We must shift market and government actions to protect health and the natural systems that support us. As a priority, we must act to phase out the most dangerous chemicals, develop safer alternatives, protect high-risk communities, and ensure that those responsible for creating hazardous chemicals bear the full costs of correcting damages to our health and the environment.

By designing new, safer chemicals, products, and production systems we will protect people’s health and create healthy, sustainable jobs. Some leading companies are already on this path. They are creating safe products and new jobs by using clean, innovative technologies. But transforming entire markets will require policy change. A first step to creating a safe and healthy global environment is a major reform of our nation’s chemicals policy. Any reform must:

Require Safer Substitutes and Solutions Seek to eliminate the use and emissions of hazardous chemicals by altering production processes, substituting safer chemicals, redesigning products and systems, rewarding innovation and re-examining product function. Safer substitution includes an obligation on the part of the public and private sectors to invest in research and development of sustainable chemicals, products, materials and processes.

Phase Out Persistent, Bioaccumulative, or Highly Toxic Chemicals Prioritize for elimination chemicals that are slow to degrade, accumulate in our bodies or living organisms, or are highly hazardous to humans or the environment. Ensure that chemicals eliminated in the United States are not exported to other countries.

Give the Public and Workers the Full Right-to-Know and Participate Provide meaningful involvement for the public and workers in decisions on chemicals. Disclose chemicals and materials, list quantities of chemicals produced, used, released, and exported, and provide public/worker access to chemical hazard, use and exposure information.

Act on Early Warnings Act with foresight. Prevent harm from new or existing chemicals when credible evidence of harm exists, even when some uncertainty remains regarding the exact nature and magnitude of the harm.

Require Comprehensive Safety Data for All Chemicals For a chemical to remain on or be placed on the market manufacturers must provide publicly available safety information about that chemical. The information must be sufficient to permit a reasonable evaluation of the safety of the chemical for human health and the environment, including hazard, use and exposure information. This is the principle of “No Data, No Market.”

Take Immediate Action to Protect Communities and Workers When communities and workers are exposed to levels of chemicals that pose a health hazard, immediate action is necessary to eliminate these exposures. We must ensure that no population is disproportionately burdened by chemicals.

The other helpful framework for ordering our thinking about safer chemicals has been created by a pair of scientists, Warner and Anastas. Their “12 Principles of Green Chemistry” provides some guidance for prospective policies – both industrial/production policies, as well as governmental policies on chemical safety.

12 Principles of Green Chemistry

1. Prevent waste: Design chemical syntheses to prevent waste, leaving no waste to treat or clean up.

2. Design safer chemicals and products: Design chemical products to be fully effective, yet have little or no toxicity.

3. Design less hazardous chemical syntheses: Design syntheses to use and generate substances with little or no toxicity to humans and the environment.

4. Use renewable feedstocks: Use raw materials and feedstocks that are renewable rather than depleting. Renewable feedstocks are often made from agricultural products or are the wastes of other processes; depleting feedstocks are made from fossil fuels (petroleum, natural gas, or coal) or are mined.

5. Use catalysts, not stoichiometric reagents: Minimize waste by using catalytic reactions. Catalysts are used in small amounts and can carry out a single reaction many times. They are preferable to stoichiometric reagents, which are used in excess and work only once.

6. Avoid chemical derivatives: Avoid using blocking or protecting groups or any temporary modifications if possible. Derivatives use additional reagents and generate waste.

7. Maximize atom economy: Design syntheses so that the final product contains the maximum proportion of the starting materials. There should be few, if any, wasted atoms.

8. Use safer solvents and reaction conditions: Avoid using solvents, separation agents, or other auxiliary chemicals. If these chemicals are necessary, use innocuous chemicals.

9. Increase energy efficiency: Run chemical reactions at ambient temperature and pressure whenever possible.

10. Design chemicals and products to degrade after use: Design chemical products to break down to innocuous substances after use so that they do not accumulate in the environment.

11. Analyze in real time to prevent pollution: Include in-process real-time monitoring and control during syntheses to minimize or eliminate the formation of byproducts.

12. Minimize the potential for accidents: Design chemicals and their forms (solid, liquid, or gas) to minimize the potential for chemical accidents including explosions, fires, and releases to the environment.

(Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, by John Warner and Paul Anastas) The success of our work to improve chemical policies depends on our ability to tap the knowledge and skills of a wide array of disciplines – chemists, engineers, economists, and others. In this mix, nurses will play an important role. Our understanding of science and human health, our trusted position in the community, and our excellent communication skills will be valuable assets to statewide and national campaigns. We are also highly organized through the ANA, state nurses associations, nursing unions, and the many nursing subspecialty organizations. Through our collective efforts, we will have the ability to influence the safety of the chemicals in our everyday lives: household cleaners, cosmetics, arts supplies…hospital supplies… really all products. This is noble and important work and I believe that nurses are already showing that they are up to the task.

To learn more about nurses’ roles in chemical safety, join the monthly Nurses Work Group call. To obtain the (800) national call-in number, contact the Health Care Without Harm office: (703) 243-0056.

Author: : Barbara Sattler, RN, DrPH, FAAN, Director of the Environmental Health Education Center at the University of Maryland where she directs the graduate program in Environmental Health Nursing. (www.enviRN.umaryland.edu).