PROJECT BRIEF

1. IDENTIFIERS: PROJECT NUMBER P066509 PROJECT NAME Philippines: Metro Manila Urban Transport - Marikina Bikeways Component DURATION 2 Years (GEF component) IMPLEMENTING AGENCY The World Bank EXECUTING AGENCY The City of Marikina – Metro Manila - Philippines REQUESTING COUNTRY Philippines ELIGIBILITY Ratified the UNFCCC Convention on August 2, 1994 GEF FOCAL AREA Climate Change GEF PROGRAMMING FRAMEWORK OP 11: Promoting Environmentally Sustainable Transport

2. SUMMARY: The proposed GEF component would promote a shift from motor vehicles to non-motorized transport (NMT), particularly bicycles, in Marikina City, metro Manila, by making NMT a safer and more convenient transport mode in the city. Its global environment objective is to slow the growth of transport-related GHG emissions. This would be achieved by: (i) shifting new transport demand towards less-polluting NMT modes; and (ii) maintaining the current demand share served by non-motorized modes. A secondary objective is to demonstrate and publicize the benefits and viability of NMT as an alternative transport mode, so as to encourage replication of this pilot NMT program in other parts of Metro Manila, elsewhere in the Philippines, and in other countries. These objectives will be achieved by constructing, evaluating and promoting the Marikina Bikeway System (MBS) - a 66km-long network of trails and road lanes specifically designed for NMT, plus bicycle parking and traffic calming systems. The network will connect residential communities with schools, employment centers, the new metropolitan train station and other public transport terminals. Provision of these NMT-friendly facilities will encourage the use of NMT modes, and connection with the public transport terminals will promote the combined use of NMT and train/bus for trips between Marikina and the rest of metropolitan Manila. The costs and benefits of this pilot NMT initiative will be thoroughly monitored and evaluated, and widely disseminated to the World Bank’s client countries and to its transport specialists. The Markina Bikeways System will be a component of the broader Metro Manila Urban Transport Integration Project (MMURTRIP), which will be co-financed by the Government of the Philippines and the World Bank. MMURTRIP’s development objective is to reduce Manila’s traffic congestion and travel times, particularly those experienced by public transport users, the majority of whom are poor “captive” users. This objective will be achieved through the improvement of street level interchanges between buses, jeepneys and Light Rail Transit (LRT), and the implementation of effective traffic management measures along major travel corridors. 3. COSTS AND FINANCING (MILLION US$) GEF Project 1.700 PDF/A 0.025 PDF/B 0.150 Co-financing of GEF Component Government 0.186

Sub-Total GEF 2.061

Other Components IBRD 60.000 Government 30.600

TOTAL PROJECT COST 92.661

5. OPERATIONAL FOCAL POINT ENDORSEMENT: NAME: Mario S. Rono TITLE: Undersecretary and GEF Operational Focal Point DATE: March 10, 2000 ORGANIZATION: Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR)

6. IA CONTACT: A. Robin Broadfield Sr. GEF Coordinator for East Asia & Pacific Region Telephone: (202) 473-4355 Fax: (202) 522-1666 / 7147 Email: [email protected]

2 A. Project Development Objective 1. Project development objective: The Project Development Objective is to manage traffic congestion and improve environmental and safety conditions, particularly those affecting public transport users. Improved street level interchange between buses, jeepneys and Light Rail Transit lines together with increased access to outer areas and improved road network hierarchy will demonstrate the efficacy of traffic management measures as a cost-effective means to manage congestion along major travel corridors, enhance the use of public transport and increase the benefit of the committed mega-projects.

2. Global environment objective: The global environment objective of the proposed Global Environment Facility (GEF)- supported Non-Motorised Transport component is to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by promoting the use of near zero-emission bicycle and pedestrian transport in the City of Marikina as an alternative to GHG-emitting motorized transport. A second objective is to evaluate and publicize the global and local benefits of NMT as an alternative transport mode to encourage replication of this pilot program in other parts of Metro Manila, elsewhere in the Philippines, and in other countries.

3. Key performance indicators: The key performance indicators of the overall project are reduced travel time, public transport usage and improved satisfaction of public transport users with the urban environment on the project corridors. The key performance indicators of the GEF component are the proportionate shift to NMT modes that it induces and the GHG emission and local environment and social benefits (and costs) that result from it.

B. Strategic Context 1. Sector-related Country Assistance Strategy (CAS) goal supported by the project: Document number: 19355-PH Date of latest CAS discussion: 05/11/99 To help the Philippines achieve its overarching goal of poverty reduction, the World Bank Country Assistance Strategy (CAS) focuses on the following seven areas, which are consistent with the Medium Term Philippine Development Plan: Address crisis effects and promote economic recovery Enhance human development and social services for the poor Accelerate environmentally sustainable rural development Promote sustainable urban development and combat urban poverty Develop infrastructure, particularly in the provinces Enable expansion of the private sector Improve governance and transparency and combat corruption. By addressing transport problems in Metro Manila area, the Metro Manila Urban Transport Integration Project (MMURTRIP) will support item 5. This is consistent with the Philippines Government's Medium Term Development Priorities, which states that the "program targets transport problems in Metro Manila for special attention". 1a. GEF Strategy/Program objectives addressed by the project: MMURTRIP’s proposed Global Environment Facility (GEF) Non-Motorized Transport component is fully consistent with the GEF’s Operational Strategy, and with the GEF’s new Operational Program 11 on Transportation, which states that “GEF will promote, amongst others, non-motorized transport technologies and measures, especially in medium-scale growing cities”. It will demonstrate that NMT networks are a low-cost, convenient and acceptable alternative method of city transportation over short-to-moderate distances, and also have significant global and local environment benefits. It is a national priority for GEF assistance, and has a strong local government, NGO and community support, and thus excellent prospects of sustainability. It has tremendous replication potential in Manila, other Philippine cities and other countries. 2. Main sector issues and Government strategy: Urban transport congestion and its related impacts is one of the Philippines’, and particularly Metro Manila’s most pressing problems,. Manila is a massive urban area, housing 10 million people, producing one-third of GDP, and comprising four cities and 17 municipalities. Relative economic prosperity (average per capita income is about US$ 1,000 per annum) has accelerated motorization and demand for mobility, causing severe traffic congestion and environmental problems. Residents perceive traffic congestion as the number one problem, followed by air pollution, garbage collection, flood control and security. About 20% of households own cars. However, despite a trend of rising car ownership, public transport has always been the dominant mode. The following table compares transport in Metro Manila with other cities in the region.

Average Travel Speed in Major Asian Cities

35 30 30 25 20 r

h 20 / 15 15 15 m

k 15 9 10 10 5 0

Vehicle Ownership and Income

Jakarta Manila Bangkok Kuala Singapore Tokyo Lumpur Cars/1000 74 85 141 464 110 255 inhabitant (1995) (1993) GDP per 1,503 2,347 6,678 5,238 24,311 57,452 capita US$ (1994) (1994) (1993)

2 Source: MMUTIS report July 1997

Data from household surveys carried out in 1996 show that, of motorized trips, 75% were by public transport (41% by jeepney, 13% by bus, 19% by tricycle, 2 % by Light Rail Transit (LRT) Line 1, 20% were by private car, 5% by taxi and a negligible proportion by Philippines National Railway. 20% of total trips were walking trips. The existing LRT Line 1 operates at capacity carrying about 350,000 - 400,000 passengers per day. The main sector issues and the Government strategy to address them are summarized below.

Inadequate urban transport strategy in Metro Manila. At present there is no unified strategy for the Metro Manila urban transport sector. Plans and policies are mode specific and sponsored by national agencies with limited regard for developing an integrated, intermodal transport system. Due to land acquisition and fiscal constraints, road network expansion has been limited (only about 75 kms of new roads have been constructed since 1982). To develop a long-term strategy, the Government is currently undertaking the MMUTIS study sponsored by DOTC and funded by JICA. Similarly, to address infrastructure and development issues which transcend the municipal boundaries of the 17 municipalities comprising Metro Manila, the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) was established in March 1995. To date, this agency has not been effective in its mandated role, especially in the area of metropolitan transport planning and traffic operations management.

Improved traffic management. Without an efficient street level collection and dispersal of light rail passengers, and traffic to and from expressways, the effectiveness of mega-investments will not be fully realized. Moreover, given the high dependence on road based public transport (buses and jeepneys), improvement in traffic flows directly affects the capacity of the public transport system and related environmental and safety conditions. In general, road construction in Manila has not taken into account the needs of buses, jeepneys and tricycle services such as stop and drop-off sites, transfer points and waiting areas. With the result that chaotic traffic conditions prevail along major corridors and near road junctions severely affecting the overall traffic flow, causing delays and increasing safety hazards. Traffic management deserves highest priority in the sector and should become the most essential housekeeping function of Manila. However, this approach requires strong coordination between agencies responsible for physical improvement (DPWH and LGUs), traffic operations and control (DPWH, MMDA, LGUs) and enforcement of regulations (Police, DOTC). To address this, MMDA was assigned the responsibility to coordinate traffic operational enforcement. Though MMDA has made some progress there is room for considerable improvement. Besides human and financial resource constraints of MMDA, strong government commitment is required to streamline the overlapping roles of national agencies and MMDA in Manila.

Enhanced access to outer areas. As Metro Manila is rapidly expanding outside the circumferal boundary of EDSA, the constraints posed by the current transport access to these outer areas is becoming more evident. People seeking work in Metro Manila experience long commutes and there is a perceived lack of accessibility by residents coupled with a poor perception of public transport services. For example both in the Marikina Valley and Rizal Province, despite lower than average household incomes, vehicle ownership is 24% against

3 around 20% in Metro Manila since people see private transport as a necessity to combat these constraints.

An improved road network hierarchy. To facilitate better dispersal of traffic over the network and reduce traffic on arterial roads, there is a need to improve the overall network capacity by improving the connectivity and capacity of existing secondary roads through implementing missing links, rehabilitating pavements, sidewalks and drainage, and controlling/removing encroachments.

Air Pollution: local and global impacts. Mobile source air pollution from transport is the major cause of air pollution and major source of GHG emissions in Metro Manila. Residents rate air pollution as the area's number two quality of life problem, after traffic congestion. The Government is pursuing a combination of public investment, fuel pricing and administrative control measures to bring mobile emissions down to a healthier level. The Metro Manila Air Quality Improvement Project, assisted by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), promotes the use of cleaner fuels and vehicle inspection. MMURTRIP will encourage the use public transport. Together, the two projects will help to reduce local transport pollution. On the global front, Philippines has ratified the UNFCCC and is a co-signatory to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. This reflects a strong commitment to reducing its contribution to GHG emissions. With respect to transport GHG emissions, one of Philippines’ strategic priorities is to encourage the use of non-motorized forms of transport in its major cities. The proposed Marikina NMT network is its first demonstration of how to achieve that objective.

Railway (Philippines National Railways). Currently rail corridors are underutilized assets and the right-of-way is encroached by squatters. The need to preserve this asset is critical to develop sustainable commuter rail operations both in the north and south of Metro Manila. The future role of the railway needs to be determined in the context of a metropolitan wide transport strategy. Government is pursuing possible privatization and concession options with the assistance of United States Technical Development Assistance (USTDA) and Asian Development Bank (ADB).

3. Sector issues to be addressed by the project and strategic choices: Among the various sector issues, the main project will concentrate on addressing the need for: (i) better traffic management by improving jeepney, bus and Light Rail Transit (LRT) interchanges on the LRT Line 2 and Line 3 corridors and at the interchanges on the South Super Highway, (ii) enhanced access to outer areas by a series of projects in Marikina Valley; (iii) an improved road network hierarchy by investing in strategic secondary roads; and (iv) addressing GHG emissions through its non-motorized transport pilot component, which will demonstrate benefits of pedestrian and bicycle facilities in Marikina. Local air pollution and railway services are being addressed with financing assistance of other donors.

The project has been developed by an inter-agency committee under the lead and chairmanship of the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) and has therefore been a vehicle to allow MMDA to undertake its mandated role as metropolitan transport planning agency. To further develop this capacity and to allow MMDA to continue to have a strategic role in the development of the project and other related activities, the Government has strong

4 commitment to MMDAs role in project implementation in two ways (a) planning and coordination of strategic metro-wide investments and (b) formulation and implementation of strategic traffic management and enforcement measures. A stronger and well equipped MMDA would enhance the effectiveness of the present project and in turn further strengthen the role of the MMDA in Metro Manila. MMDA has little experience with actual management of implementation of works contracts and the project will give MMDA the opportunity to develop this capacity. Implementing traffic management works should be the role of such an authority. The strategic choices made in the project development include a focus on: (i) those corridors which carry the heaviest traffic and public transport passengers; (ii) interventions which are complementary to the committed mega-projects rather that major investments; (iii) projects which encourage public transport; (iv) development of access to the outer areas; (v) sub- projects where the resettlement is minimized; and (vi) sub-projects which are considered to be possible to implement within the time-scale planned. 3a. Sector issues to be addressed with Global Environment Facility (GEF) support: Global Environment Facility (GEF) support is requested to overcome the barriers to expanded use of non-motorized transport (NMT) in Marikina, one of Manila’s more progressive cities. By shifting transport demand to these environmentally-friendly modes, it would mitigate the large and growing GHG emissions from motorized transport in Marikina. Under the GEF Alternative, the City of Marikina (one the four cities that comprise Metro Manila) would modify its transport development program, which currently focuses exclusively on road expansion and improvement, to actively promote greater use of bicycles and walking as alternatives to motorized transport. This would encourage a shift from motorized transport to these environmentally-friendly options. The main barrier to this shift is travelers’ perception and reality that bicycles and walking are relatively slow, inconvenient and unsafe transport options. This barrier stems from the lack of appropriate facilities for bicyclists and walkers. With GEF support, these barriers would be overcome by: (a) constructing a pilot network of bicycle and pedestrian lanes and paths along well-traveled commuter routes in low-income areas (on existing roads and public access areas); (b) installing bicycle storage facilities at light rail stations to encourage joint NMT/public transport use; and (c) publicizing and promoting these alternative transport modes through an awareness campaign and safety program. Such investments have not been made previously and would not be made without GEF support because: (a) political pressures encourage investment in the expansion of road capacity for motor vehicles, rather than bicycles; (b) the demand for and benefits of NMT modes have not been demonstrated in Marikina or in other similar localities; and (c) the accepted methods of transport project economic analysis do not capture environmental externalities when assessing the feasibility of alternative investments. With respect to point (c), both the Philippines National Economic Planning Agency (NEDA) and the World Bank currently view transport economic benefits as stemming from three main sources, namely: (i) vehicle operating cost savings; (ii) time cost savings; and (iii) accident cost savings. In practice, only the first two are used in the current methodologies, which focus only on evaluating motorized traffic options. Transport related externalities caused by congestion and pollution are not captured in these methods of analysis.

5 There have been several attempts to promote analytical consideration of other benefits, such as social and environmental benefits, from non-motorized transport. Although it is widely accepted that there are environmental benefits to non-motorized transport, there is no accepted method for estimating these. This project will develop a methodology for calculating the GHG emission benefits and demonstrating the impact on motorized traffic levels of the bicycle network which can then be applied to the evaluation of further projects of this type. Since political commitment is a key to the success of any development initiative, a strategic choice was made to limit the bicycle network to one very interested city, and to use its experience for demonstration purposes. Its design is based on a proposal from the Department of Public Works and Highways, the Urban Roads Project Office, and on a personal request from the Mayor of the City of Marikina. The City of Marikina funded the preliminary diagnostic work on the concept and approached the GEF and the World Bank for assistance with funding its incremental cost. The proposal has been endorsed and confirmed as a national priority for GEF assistance by the country’s GEF Focal Point. C. Project Description Summary 1. Project components: The MMURTRIP project has been agreed by the inter-agency project committee, the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), as the implementing agency, and the Metro Manila Development Authority and endorsed by the Metro Manila Mayor's Council under the chairmanship of MMDA. The project includes the following components located in the 17 municipalities of the Metro Manila area:

Traffic management improvements on LRT Line 2 corridor; EDSA LRT Line 3 corridor; and the Bicutan and Alabang interchange improvements on the Southern Corridor. MARIPAS Access Improvements in Marikina Valley including the Marikina Bridge and Access Roads component, Marcos Highway and Ortigas Avenue Extension. Secondary Roads Program (17 road sections as listed in Annex 2). Non-Motorised Transport (NMT) Pilot in the City of Marikina in Metro Manila supported by Global Environment Facility (GEF) grant funding. Institution Building/Technical Assistance.

A feasibility study on all these components was completed by Halcrow Fox in July 1998. The project is divided into two Phases (I and II). The detailed engineering for the Phase I components of the project will be in completed October 2000. The detailed engineering for the remaining Phase II components of the project will commence October 2001.

6 Indicative Bank- % of Component Sector Costs % of financing Bank- (US$M) Total (US$M) financing 1. Traffic management Urban Transport 0.0 0.0 improvements LRT Line 2 corridor Urban Transport 4.27 4.6 2.99 4.8 EDSA LRT Line 3 corridor Urban Transport 4.47 4.8 3.13 5.0 Southern corridor - Bicutan Urban Transport 2.98 3.2 2.09 3.3 interchange improvements Southern corridor – Alabang Urban Transport 2.98 3.2 2.09 3.3 interchange improvements 2. MARIPAS Access Improvements Urban Transport 44.28 47.9 31.00 49.5 Marikina Bridge and Access Urban Transport 0.00 0.0 0.00 0.0 Roads Marcos Highway Urban Transport 0.00 0.0 0.00 0.0 Ortigas Avenue Urban Transport 0.00 0.0 0.00 0.0 3. Secondary Roads Program Urban Transport 30.59 33.1 18.68 29.8

4. Non-Motorised Transport (NMT) Urban Transport 1.80 1.9 1.70 2.7 5. Institution Building/Technical Institutional 1.00 1.1 1.00 1.6 Assistance Development Total Project Costs 92.37 100.0 62.68 100.0

Note: The cost of detailed engineering design and supervision is included in the cost of each physical component.

1a. Description of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) supported component:

Global Environment Facility (GEF) grant funding is requested to support the development, evaluation and replication of a system of bicycle and pathways, and related facilities, in the City of Marikina. Together they comprise the project’s Non-Motorized Transport (NMT) component. This component will serve to demonstrate the benefits of these alternative modes of transport. NMT includes bicycles and pedicabs (non-motorized passenger transport), and walking. A feasibility study of the component, conducted by the University of Philippines National Centre for Transportation Studies Foundation, Inc., in association with the City of Marikina administration, has been completed with PDF A grant funding support from the GEF and is available for review. Background and baseline scenario. Marikina is a medium-sized city of about 360,000 people, situated at the eastern border of the Metro Manila administrative area. It is one of the 17 municipalities that comprise Metro Manila. Being located on the periphery, Marikina’s transport congestion has not yet reached the intolerable level of the inner city. So within Marikina, about 10,500 daily trips (2.9% of all trips) are still made by bicycle. (In comparison, approximately 160,200 trips (1.7 %) are made by bicycle in Metro Manila). However, under the

7 baseline or “business as usual scenario”, increased motorized traffic in Marikina will reduce the safety of bicycle travel and the use of bicycles to the lower level now experienced in the rest of Metro Manila. Objective. Given these characteristics of current high and accepted bicycle usage and lower levels of congestion, the City of Marikina is considered an excellent site in which to establish a pilot bicycle network to demonstrate the viability and benefits of this mode of inner- city transport. By doing so, its popularity can be sustained and even enhanced, despite creeping motorization, which, elsewhere in Metro Manila (and many other Asian metropolises), is “crowding out” bicycles as a viable mode of transport. Benefits. In addition to its global environment benefits, the bikeway system should create some modest domestic benefits by marginally reducing motorized traffic and congestion. This in turn will decrease in pollutant emissions. If successful, it will demonstrate the benefits and viability of bicycles and other NMT transport, and thus (hopefully) encourage the development of similar facilities elsewhere in Metro Manila and in the Philippines. A rigorous monitoring and evaluation system will capture its benefits and be used to promote its replication.

Description. The Non-Motorised Transport (NMT) system will comprise the following components:

49.7 km of segregated bikeways on existing roads, and 16.6 km of bikeways along the Marikina river, connecting to the new LRT station; traffic slowing and pedestrian facilities around schools and market areas, and provision of bicycle parking facilities at key interchanges; lighting, where necessary, to ensure safety after hours; a public awareness campaign; a bicycle safety program; a rigorous monitoring and evaluation program and major dissemination effort.

The bikeway network will connect residential communities with schools, employment centers, the new LRT station and other public transport terminals, where appropriate parking facilities will be created. The connections with the public transport terminals will promote the use of both NMT and LRT/bus for trips between Marikina and the rest of the metropolitan area, thus reinforcing the modal shift away from cars and maximizing the global benefits. A series of pedestrian areas and traffic slowing mechanisms will encourage walking trips. Nearly 50 km of the 66 km bicycle network will be built on existing roads, of which 30.8 km will be within the existing roadway width and 18.9 km will require some road widening to accommodate the bicycle lanes. Nearly 17 km will be along the banks of the Marikina river, connecting to the LRT station, of which 8.4 km will be new construction and 8.2 km will involve the upgrading of existing walking paths.

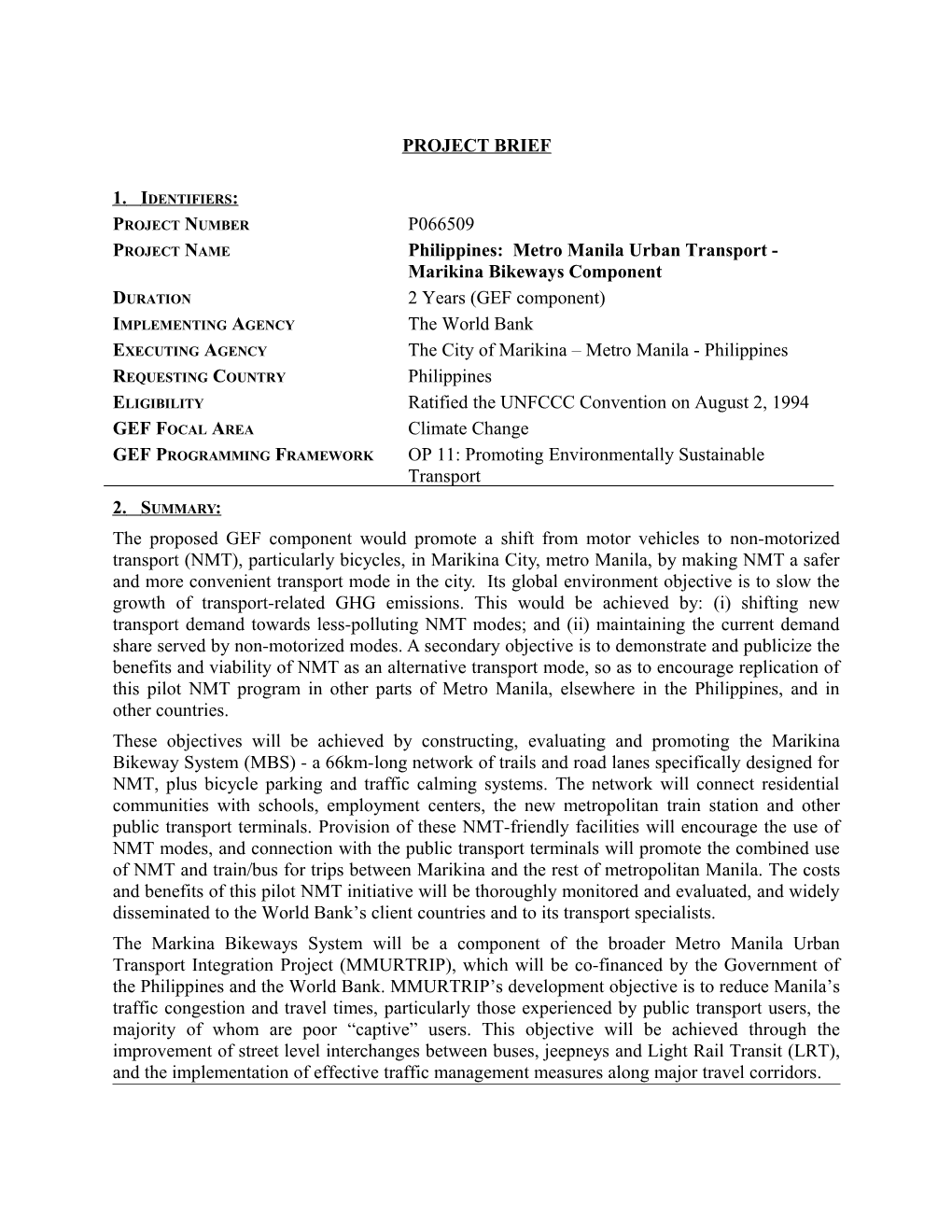

A typical design is shown in figure 1 A below. Bicycle lanes within the existing roadway will be physically separated from other traffic. On two-way roads, the bicycle lanes will be on each side of the road. On one-way roads, they will be on one side only. The lanes will be 1.5 m wide, and a physical barrier between the adjacent traffic and the bicycle lane will be provided. Traffic counts were carried out at 7 strategic locations in the City of Marikina in October 1999,

8 indicating approximately 70 bicycles in the peak hour. Thus the proposed 1.5 m width of the bicycle lanes is considered sufficient (Netherlands recommends 1.5 m for 0-150 bicycles per hour in peak hour). Issues of roadside access to shops and properties will be addressed during detailed design. Where the road pavement has deteriorated, reconstruction may be necessary. Green asphalt or concrete will be applied to designate the bicycle lanes. Where necessary, new facilities will be constructed to facilitate access to public mass transit, for example, the new LRT station on the southern boundary of the City of Marikina. This will interlink the NMT system with the main components of the MMURTRIP project namely, the Marikina Bridge and Access Roads component and the Marcos Highway component.

Figure 1 A. Typical road/bikeway cross section - Bayan - Bayaanan Road (metres)

15.6

1.5 12.6 1.5

Cost. The NMT system is estimated to cost about US$ 1.8 million. Marikina City had made no provision in its budget to fund the system, and its local economic benefits are uncertain, so its total cost is incremental. Global Environment Facility (GEF) grant financing US$ 1.7 million is sought to help defray this cost. The City of Marikina will finance the balance of US$ 0.1 million. The cost breakdown is given in the table below. The cost of detailed engineering design, survey costs and supervision is estimated at 10% of the cost of the physical works. The cost of the 66 km network is approximately $22,000 per km, including the 10% for detailed engineering design, survey costs and supervision.

Component Indicative GEF Marikina Costs (US$000) Non-Motorized Transport 1,800 1,700 100 - Bikeways (66 km) 1,500 1,450 50 - Traffic slowing and pedestrian facilities 100 80 20 - Lighting 70 60 10 - Public Awareness 40 35 5 - Bicycle Safety 40 35 5 - Evaluation/dissemination 50 40 10

9 1b Monitoring and Evaluation of the GEF Component The GEF component will be carefully monitored over a five year period and thoroughly evaluated at the end of this period. Monitoring will cover: (a) progress with the physical, awareness safety and dissemination aspects; (b) use of the facilities by alternative NMT modes; (c) its impact on motorized transport volumes, congestion, travel times and costs; (d) resulting GHG emission impacts; and (e) local pollutant levels and local environment benefits. Design of the M & E system and indicators will be completed during the final preparation phase. D. Project Rationale 1. Project alternatives considered and reasons for rejection:

To combat the rapidly growing imbalance between the transport capacity and demand, the Government of the Philippines embarked on building several light rail lines and expressways mostly with the assistance of private developer financing. Though only three of these mega- projects are under implementation, from the outset they have raised issues of physical conflicts between them and other improvements undertaken by sector agencies DOTC, DPWH and private sponsors. More specifically, there has been limited attention paid to: (i) transfers between LRT Line 1 and 2 and Lines 2 and 3; (ii) the need for developing LRT terminals as major transfer stations between LRT and bus, jeepney, and tricycle services; (iii) safe and efficient access and egress near LRT stations and expressways; and (iv) improvement in traffic flow conditions in general along major corridors to improve the efficiency of bus, jeepney and general traffic flows.

The rationale for this MMURTRIP project has therefore been to address these areas and develop complementary measures to the mega-projects to ensure that the maximum benefits are gained from them and that the traveling public is better served. An alternative option would have been to finance further mega-investments, however this was rejected since other donors (in particular JBIC) are investing in such projects and the continued and sole application of such projects are not considered to be a long-term solution if complementary measures are not taken. In addition the almost impossible task of implementing resettlement and land acquisition in Metro Manila eliminated components which required major construction. The use of an Adaptable Program Lending facility was not considered to offer any advantages over a Sector Investment Loan.

2. Alternatives to the GEF component and reasons for their rejection:

In the framework of the MMURTRIP, other initiatives that are consistent with the GEF Transportation OP, and therefore could have qualified for GEF support, are the promotion and introduction of cleaner fuel and improved engine technology and a system of emissions control, both for private and public transportation modes in the entire metropolitan area. However, the Government of Philippines is already promoting similar initiatives with the support of a US$ 300 million program loan from the Asian Development Bank, and therefore it was considered that these aspects are being adequately addressed. 3. Lessons learned and reflected in the project design: During the past decade, no World Bank operation was undertaken in the Metro Manila urban transport sector. The projects funded by other agencies have indicated the difficulties of resettlement in Metro Manila. The project components have therefore sought to minimize the

10 need for resettlement and several sub-projects have already been deleted from the original project proposal.

The World Bank has specific experience in urban transport projects throughout the world. In particular, several urban transport projects have been undertaken which have demonstrated the benefits of the traffic management approach to improving the urban congestion problems and the high rates of return of such projects. An Urban Transport Improvement Project started in November 1998 in Vietnam which consists solely of traffic management interventions.

3a. Lessons learned and reflected in the GEF component’s design: The future of Non-Motorized Transport (NMT) in Manila and in many Asian cities is threatened by growing motorization, loss of street space for safe non-motorized vehicle use, and changes in urban geography prompted by motorization. Transportation planning and investment in most of Asia has focused on motorized transportation, generally ignoring NMT. Without changes in policy, NMT will continue to decline precipitously in the coming decade, with major negative effects on air pollution, energy use, urban sprawl, and the employment and mobility of low-income people. The experience of cities in Japan, the Netherlands, Germany, and several other European nations demonstrates that modernizing urban transportation requires not total motorization but the appropriate integration of walking, NMT and motorized transportation. As in these European and Japanese cities, in which a major share of trips are made by walking and cycling, NMT can play an important role in the urban transportation system of Metro Manila and other Asia cities in the coming decades. Experience has also demonstrated that transportation investment and policy are the primary factors that influence NMT, and can have an effect on the pace and the quality of motorization. Cities that adopted well-timed policies promoting NMT witnessed the major growth of bicycle use despite increased motorization. The policies adopted provided for extensive bicycle paths, bicycle facilities, and integration with public transportation as well as adequate promotion of the mode through awareness campaigns and safety programs to sensitize the motorized vehicle users.

4. Indications of borrower and recipient commitment and ownership: The MMURTRIP project was proposed in 1997 by an inter-agency committee chaired by MMDA and consisting of MMDA, DPWH, DOTC, DOF and NEDA. Through a memorandum of agreement among these agencies, the project was established to identify, plan and prepare road and related infrastructure in Metro Manila. Subsequent workshops by this committee and consultations with Metro Manila local governments developed a list of investments that now form key components of the project. In July 1998 an initial proposal was presented to the Infrastructure Committee of the NEDA Board. DPWH is including the project in its 3-year rolling priority investment program for 1999-2001. The project was presented to the NEDA Board August 1999 and endorsed for implementation subject to the more direct involvement of MMDA. Subsequent proposals on MMDA's involvement have been endorsed. There is strong political commitment to the project in particular in support of the development and involvement of MMDA.

11 The local governments of Marikina, Rizal and Pasig, in an association called MARIPAS, joined together and with the DPWH regional office drew up a plan to tackle their various common transport problems. The MMURTRIP project will implement some of these plans, namely the Marikina Bridge and Access Roads, Marcos Highway, and the Ortigas Avenue Extension components.

4a. Indications of recipient commitment and ownership of the GEF supported component:

The Non-Motorized Transport (NMT) component was proposed by Department of Public Works, Urban Roads Project Office, and subsequently endorsed by the Mayor of the City of Marikina in a request to the World Bank for assistance with possible Global Environment Facility (GEF) funding. The current Marikina administration continues to demonstrate commitment to NMT and to the related environmental issues. It has funded preliminary diagnostic work on the component and has set up a counterpart team composed by staff of the various city's offices (Settlement, Health, Engineering, Administration). This team will be responsible for liaison and coordination between the various units of the administration and with the component’s consultants and contractors.

Moreover, to inform the process of designing and implementing the Non-Motorized Transport component, Focus Group Discussions have been held with various stakeholders from the communities and businesses that will be affected by the project. These discussions have confirmed strong support for the use of bicycles and the need for appropriate facilities. The local newspaper has also published an article on the so-called Marikina Bikeways Project. The component’s information campaign will help to maintain the momentum and continue promotion and awareness building.

5. Value added of Bank and GEF support for this project: In its Country Assistance Review, the Operations Evaluation Department of the World Bank recommends that the Bank should remain active in the transport sector, given the sector's important strategic role, the existing institutional weaknesses in the sector, the need for public investment, and the considerable experience in transport that the World Bank has to offer. The World Bank is well prepared to help in transport strategy implementation having assisted in formulating the Philippines Transport Sector Strategy in June 1998. The value of GEF support in this project lies in supporting an innovative NMT component of the project which otherwise would not find funding support. E. Summary Project Analysis (Detailed assessments are in the project file) 1. Economic: Cost benefit NPV=US$ million; ERR = %

Economic evaluation of the major components has been undertaken using cost-benefit analysis with a 15% discount rate. As is standard practice in evaluation of transport projects, the benefits are based on vehicle operating cost (VOC) savings and value of time (VOT) savings. The benefits arising from accident cost savings or environmental improvements have not been included, given the difficulty of these type of calculations. However, improvements in safety will result due to reduced potential conflicts between vehicles and pedestrians and would lead to

12 increased benefits. The costs include the initial construction, right-of-way acquisition and future maintenance costs.

The greatest benefits are derived from travel time savings, with relatively fewer benefits from vehicle operating cost savings. The travel time savings include the valuation of work travel time, commuting travel time and leisure travel time. Commuting and leisure time has been valued at 50% of work time. Assigning a value to leisure travel time is in line with World Bank practice in evaluation of urban transport projects. The local evidence indicates that this seemingly high value of 50% is not unwarranted in the Manila context (the average normally used is 25%-30% of work time). The value of work time ranges from 41 to 52 pesos/hour (1997 prices 1 US$ = 29.4 Pesos; US$ 1.39 to US$ 1.76 per hour) and is based on MMUTIS household interview survey data.

The assumptions made in the analysis include a 5 year life span for the traffic management improvements largely those on LRT 2 and EDSA and a 20 year life-span for the components with more substantial components; traffic growth rate of 2% within and along the EDSA corridor and 5% outside the EDSA corridor which reflects the currently observed situation and is as a result of population growth differentials and network capacity constraints. In the project costing, 1997 prices have been used with exchange rate of 1 US$ =PhP29.4.

The results of the analysis show high returns. World Bank experience with similar traffic management projects in other countries demonstrates that they consistently produce high returns because of the significant benefits such improvements generate with relatively small investments. The results of the analysis are as follows:

Economic evaluation of project components Indicative Section ERR based ERR based Cost length On vehicle on vehicle Component (US$ (km) operating operating million) cost savings cost savings plus time savings 1. Traffic management improvement LRT Line 2 corridor 4.27 5.5 km 61% 481% EDSA LRT Line 3 4.47 18% 154% corridor Bicutan interchange 2.98 n/a 37% 192% Alabang interchange 2.98 n/a 56% 519% 2. MARIPAS Access Improvement Marikina Bridge & Access 20.0 n/a 4% 19% Roads Marcos Highway 10.980 22% 162% Ortigas Avenue Extension 233% 1065% 3. Secondary Roads 30.59

13 Program: SSH West/East Service 95% 111% Road Quirino Highway 279% 3848% M. de la Fuente (Trabajo) N/a 15% Banaue Avenue 47% 78% Quezon Boulevard 235% 243% 10th Avenue 47% 58% Pedro Gil/New Panaderos 180% 288% D. Romualdez 8% 30% Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue 99% 118% Pasong Tamo 45% 57% Antonio Arnaiz Avenue 30% 194% Tayuman 39% 41% Legarda 117% 163% Jacobo Fajardo. N/A N/A Don Mariano Marcos Ave 35% 107% North Avenue 28% 83% Aurora Boulevard 9% 97% Moriones N/a 30% Total

1-A. Incremental Cost of the GEF supported component :

In order to determine the incremental costs and global benefits of this component, a pre- feasibility study was undertaken, financed in part by a GEF PDF Block A Grant. The preliminary results of the study and the data collected have been used to estimate the global benefits in terms of GHG emissions reduction, compared with a Baseline case in which the component is not implemented, and to confirm that the component’s costs are incremental. The analysis is summarized in Annex 2.

More detailed analysis of the GEF component’s potential impact on transport demand and modal patterns, and of its resulting global and local environment benefits, will be conducted during the final design stages. This analysis will also identify the indicators and thresholds that will be used for monitoring and evaluation, and the cost-benefit ratios that will be calculated, which will permit the comparison of this option’s GHG mitigation cost-effectiveness with those of other transport options.

2. Financial : NPV=US$ million; FRR = %

No financial evaluations of the components have been carried out since this is not appropriate for this project. In terms of the financial impact of the project on the government budget, DPWH has included the project in their investment program. Currently there is around PhP300 million (US$ 7.7 million equivalent; exchange rate of assumed 1 US$ =PhP 39) assigned in year 2000 and PhP2.2 billion (US$ 56 million equivalent) in the following years.

14 Fiscal Impact:

3. Technical:

The project aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of traffic management measures as a cost-effective means of reducing congestion. Little use of this approach has been made to date in the context of Metro Manila where the focus has rather been on mega-investments. Traffic management is however a well-recognized tool in urban transport for maximizing the efficiency of the existing road space and is suitable where the scope for expanding road space is limited due to cost and environmental concerns.

4. Institutional: a. Executing agencies: Lack of MMDA’s effectiveness during and after the project implementation is a critical risk for the sustainability of the project. To mitigate this risk MMDA’s participation was ensured throughout the project preparation. b. Project management:

5. Social: The project will have social risks associated with disruption caused by the works. The project does target low income groups as discussed under the section on target population however the project does not meet the requirements to be classified as poverty targeted.

6. Environmental assessment: Environment Category: B Environment. The project is rated Category B. The environmental issues are of a lesser concern since identified projects will: (i) improve the urban environment for pedestrians and public transport users; (ii) improve public transport service which would have a positive impact on the environment; and (iii) discourage through traffic within residential areas.

Nevertheless, it will be necessary to ensure that all the project components meet all environmental clearance requirements of GoP and the World Bank. The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and the World Bank will determine whether an EIA is required or not for the sub-projects. To establish this, the Environmental and Social Unit in DPWH is carrying out an initial screening exercise. There is a Memorandum of Agreement between the DPWH and the Environmental Management Bureau (EMB) of the DENR on the procedures and guidelines for environmental screening and review to be carried out for roads and highway projects. DPWH will ensure that this project meets those guidelines for screening, scoping and detailed environmental analysis if necessary in accordance with all the requirements as specified in the DENR administrative order 96-37 (DAO 96-37) on EIA.

15 The project will also ensure that all construction contracts for sub-projects have appropriate clauses dealing with environmental impacts. Most of the impacts associated with a project such as this will be short-term (i.e. during construction) but still need to be addressed. Construction contracts will need to spell out responsibilities for handling and disposal of solid waste, toxic waste materials (gasoline, oils, and other byproducts from surfacing materials), removal and disposal of any spoil, specifications of noise limits, dust suppression, public safety measures, etc. DPWH and DENR will be involved with describing the specifications and standards to be met. Resettlement and Land Acquisition. Only two project components involved land acquisition. The Marikina Bridge and Access Roads component involved resettlement and land acquisition. All resettlement and land acquisition was completed prior to request for World Bank financing of this component. The Don Mariones Marcos Avenue Extension secondary roads component involved land acquisition. No resettlement was involved. The land acquisition will be completed as a condition of project appraisal. The land acquisition will be done in line with World Bank guidelines OD 4.30 and in accordance with the Department of Public Works and Highways Resettlement Policy which was agreed with the World Bank under the recently effective NRIMP-1 project. A compensation report on both the resettlement and land acquisition is included in the project files. The review of the previously completed resettlement is included in the report and found to be satisfactory.

7. Participatory Approach (key stakeholders, how involved, and what they have influenced or may influence; if participatory approach not used, describe why not applicable): a. Primary beneficiaries and other affected groups: The development of the MARIPAS Access improvements are based on consultations with the local government units of Marikina, Rizal and Pasig. In an association called MARIPAS, they have joined together, and with the DPWH regional office, have drawn up a plan to tackle their various common transport problems, which will now be implemented under the project. Further participation with the MARIPAS LGUs and other affected LGUs will continue under further project preparation. Preparation of the proposed GEF component has been led by the Marikina city government, assisted by a local environment NGO. The component’s design and estimated benefits are based on the results of representative sample study of local peoples’ transport patterns and modal preferences. Plans for the NMT network have discussed at local government meetings and summarized in the local newspaper. The reaction of local people to the proposed initiative has been overwhelmingly positive. b. Other key stakeholders: There has been extensive consultation with the LGU mayors and their technical staff. Regular consultation meetings were held during each World Bank mission and specific consultation meetings were hosted by MMDA on February 17, 2000. There is strong commitment from the LGUs. There is also public participation conducted by the LGUs in each of their constituencies. A pamphlet on the project was prepared and distributed in the local

16 language. The project has MMDA formal endorsement and endorsement from the council of mayors. F. Sustainability, Replication and Risks 1a. Sustainability: The main project aims to demonstrate the effectiveness of traffic management measures. The sustainability of these measures will depend on the willingness and effectiveness of MMDA, LGUs and related agencies in enforcing traffic management measures. Lack of MMDA’s effectiveness during and after the project implementation is a critical risk for the sustainability of the project. To mitigate this risk MMDA’s participation was ensured throughout the project preparation.

Sustainability of the GEF component will require effective maintenance of the NMT facilities. Marikina’s good track record on road maintenance, its strong commitment to the NMT component, community and NGO pressure, and the component’s awareness program should ensure that its benefits are sustainable. 1b. Replication:

Replication is one of the key objectives of the GEF component. It will include a replication strategy and action plan that will be completed during final preparation. The component’s monitoring and evaluation system will provide the inputs to that plan. The outputs will include: (a) a dissemination plan within the metro-Manila area; (b) initiatives to disseminate the results and lessons learned to transport planners in other major cities; and (c) plans for disseminating the component’s modal impact and cost-benefit methodologies within the World Bank, to the GEF, and to transport planners in other development agencies.

2. Critical Risks:

Risk Risk Rating Risk Minimization Measure From Outputs to Objective Implementation of complementary M MMDA’s participation was ensured traffic enforcement measures such as throughout the project preparation. MMDA control of frontage activities, is a direct participant in project adherence to the traffic rules, implementation and a thus being a key proposed traffic circulation strategies stakeholder they will have an interest in and general traffic management by ensuring sustainability of the impact of the MMDA and related responsible project. agencies and LGUs

Participation and cooperation of M LGUs will continue to be involved in the LGUs project implementation and ongoing consultation with the LGUs has been undertaken.

17 From Components to Outputs

MMDA will be implementing some H Institution building support will be key components in the project; provided to MMDA. Options for financial MMDA has no experience of management on a fee basis by implementing a project under World Government Financing Institutions may Bank funding; in addition MMDA is a be considered. Components of the current very weak agency. Air Quality Project are being implemented by MMDA and institution building activities under this project will aid the MMURTRIP project. Procurement delays both under H DPWH and MMDA.

Timely provision of counterpart funds. M Review of government budget situation by country team Overall Risk Rating M

18 Annex 1: Project Design Summary

PHILIPPINES: METRO MANILA URTRIP

Sector-related CAS Key Performance Monitoring & Critical Assumptions Goal: Indicators Evaluation (from Goal to Bank Mission) Poverty reduction through "development of infrastructure to support growth" and "accelerating environmentally sustainable rural and urban development". Sector-related CAS Improved transit capacity Public opinion surveys (Goal to Bank Mission) Goal: and modal integration in That the macro- Improve deteriorating Metro Manila (pg 14) economic environment urban transport situation remains favorable in Metro Manila

Project Development Outcome / Impact Project reports: (from Objective to Objective: Indicators: Goal) To manage traffic Reduced travel time Travel time surveys along Effective coordination congestion and improve experienced by transport the project corridors between DPWH, LGUs, environmental and safety users before and after the DOTC and MMDA conditions, particularly improvements those affecting public Maintained current share transport users of public transport usage Travel surveys on the project corridors Public opinion surveys Improvement in the urban environment experienced by public transport users and ease of access/egress from LRT stations

Global Objective:

Reduce GHG emissions Projected and actual Pre-project and periodic Impact of NMT and demonstrate the GHG emissions from transport emissions component on future environmental benefits transportation in inventories. modal patterns can be and viability of NMT Marikina city. distinguished. Evolution of NMT modal Pre-project estimates, Baseline modal share in Marikina city. projections and actuals. projections are realistic.

1-1 NMT schemes evaluated Number of WB transport Clients want NMT by World Bank and projects that review NMT options reviewed and are developed by clients. and actual NMT schemes convinced of benefits.

Output from each Output Indicators: Project reports: (from Outputs to component: Objective)

1. Traffic management Throughput at Reduction in travel time improvements have interchange points and increased traffic improved the efficiency increased. throughout on selected of the bus/jeepney corridors interchange operations, access to LRT stations MMUTIS monitoring of and passenger and travel time - baseline pedestrian facilities surveys and “after” surveys of travel time and public transport use Before and after surveys 2. MARIPAS Access Number of routes now improvements have available as direct links improved access to the Marikina Valley

3. Efficient Reduction in travel cost hierachization of for low income groups Secondary Roads has on those routes improved traffic dispersal and increased capacity

4. Development of Increase in number of NMT facilities has people using non- improved public motorized transport transport accessibility means along project and mobility of low routes income users Increase in use of NMT- public transport combined mode 5. Increased institutional capacity has improved metropolitan governance and strengthened local government functions

1-2 Annex 2: Incremental Cost Analysis

1. Development Goals and Global Environmental Objectives

Background Metro Manila, is a massive urban area that accommodates about 10 million people and comprises 17 different municipalities. By 2010, it is expected to become a massive conurbation of about 23 million people. This increase in population has been coupled with an expansion of the urban area, which today has reached about 800 square kilometers. As Metro Manila becomes more and more densely populated, commercial developments intensify and the living environment degrades further. Land-use in city centers, once very densely inhabited, gradually changes. Dwellers move to outer areas while commercial/business developments take place. With more households opting to live outside the inner area of Metro Manila, and with jobs and school getting farther away, the number of trips and the trips distances are expected to increase. Moreover, economic prosperity has accelerated motorization and demand for mobility, causing severe traffic congestion, and serious air pollution particularly in the inner areas. Without effective action, these problems will worsen over time as the area continues to grow. Residents currently rate traffic congestion as the number one quality of life problem, and air pollution, the largest source of which is motor vehicles, as problem number two. The City of Marikina, one of the municipalities of Metro Manila, and a rapidly growing municipality of about 360,000 situated on the eastern border of the Metro Manila administrative area, presents all the features of this urbanization trend. Its population between 1980-1995 has been increasing at a faster pace then the Metro Manila average. The growth in population is associated with an increased demand for mobility, both within its administrative borders and to central and other districts of Metro Manila. The number of passenger trips is expected to increase from the current average of 496,000 trips/day to about 1,200,000 by 2015. At the same time, the changes in social composition are influencing the car ownership ratio, which tend to level to the values for the inner areas. The increased demand coupled with increased car ownership will boost Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions unless alternative measures to control these emissions are developed and successfully implemented at an early stage. Moreover, within the City of Marikina, more than 2% of all trips are by bicycle, but the anticipated increase in traffic and pollution will likely cause the disappearance of this mode of transportation, a pattern already experienced in inner Metro Manila (and in many other Asian metropolis), where bicycles are being basically "crowded-out".

The Metro Manila Urban Transport Integration Project To address the deteriorating urban transport situation and the resultant detrimental environmental situation, the Metro Manila Urban Transport Integration Project (MMURTRIP) is currently being prepared with funding support from the World Bank and the Government of the Philippines. The development objective of the MMURTRIP is to reduce congestion and travel times and improve environmental and safety conditions, particularly those experienced by public transport users - the majority of whom are poor “captive” users. This objective will be achieved

2-1 through the implementation of effective traffic management measures along major travel corridors. These measures include the improvement of street level interchange between buses, jeepneys and Light Rail Transit (LRT) lines together with increased access to outer areas and improved road network hierarchy. At the same time, the project aims to demonstrate the value of such traffic management measures as cost-effective means of reducing congestion along the main travel corridors, thus enhancing the use of public transport and the efficacy of the private sector sponsored “mega-projects”. The major quantified benefit resulting from MMURTRIP development would be a reduction of congestion and travel times along the main travel routes leading to an increased use of public transport. A major unquantified benefit of the project will be an improved urban environment and increased safety. The project in fact would provide facilities to safeguard pedestrians in and around LRT stations and other public transport interchanges, where due inadequate facilities, pedestrians cause road traffic disruption and are exposed to safety hazard. The Proposed GEF Supported Component The proposed Global Environment Facility (GEF) supported project, or the GEF Alternative, which will be implemented as a component of the broader MMURTRIP, consists of the design and operation of a system of bike trails and designated lanes for Non-Motorized Transport (NMT) which will connect residential communities with schools, employment centers, the new metropolitan train station and other public transport terminals, where appropriate parking facilities will be created. Its development will help avoid the crowding-out phenomena mentioned above. Furthermore, the connection with the public transport terminals will promote the use of NMT combined with train/bus for trips between Marikina and the rest of the Manila metropolitan area. The global benefits stemming from the development of the project consist of the reduction of expected traffic and congestion, and the consequent decrease in emissions of GHG and other pollutants with respect to the current situation. An additional indirect benefit, of no lesser value, will be to demonstrate the benefits and viability of bicycles and NMT transport so that similar facilities might be adopted and developed elsewhere in Metro Manila and in the Philippines, recognizing that this form of transport is sustainable, non-polluting, inexpensive, and a good alternative for commuting. 2. Role of the GEF Alternative in Removing Specific Barriers to NMT Use The GEF Alternative will help to remove the physical and perception barriers that hinder the use of NMT in Marikina, and the analytical barriers that preclude its consideration and acceptance by transport planers in Marikina, other cities, and by development agencies, including the World Bank. In the City of Marikina, the main barrier to a greater use of bicycles and other NMT modes, including walking, is the perception and reality that bicycles and walking are unsafe transport options, because of the danger from and dominance of motorized forms of transport. This is due to the absence of appropriate facilities for bicyclists and walkers and to traffic congestion. Under the GEF Alternative, the City of Marikina would modify its transport development program, which has focused almost exclusively on road investment, to develop appropriate facilities for and to actively promote greater use of bicycles and walking as alternatives to motorized transport.

2-2 Non-physical barriers to NMT also exist, specifically: (a) the failure of standard transport project economic analysis to capture environmental externalities when assessing the feasibility of such investments; and (b) political pressures and a planning mentality that, to alleviate congestion, encourage investment in the expansion of motor vehicle road capacity rather than NMT facilities. Both the Philippines National Economic Planning Agency (NEDA) and the World Bank consider that transport economic benefits occur from three main sources, namely: (i) vehicle operating cost savings of existing and future traffic; (ii) time cost savings; and (iii) accident cost savings. In practice, only the first two are used in the project analysis. Environment and social transport-related externalities caused by congestion and pollution are not captured at all in these analyses There have been several attempts to promote analytical consideration of a wider range of benefits, such as social and environmental benefits of NMT. Although it is widely accepted that projects aiming to increase the use of NMT generate such benefits, there is no established method for estimating them and hence justifying these investments. When agencies simply look at conventional options and seek a minimum 15% Economic Rate of Return (ERR) based on conventional methods, innovative, environmentally-friendly options such as NMT are either not considered at all or are not judged to be economically viable. The results of the GEF Alternative will be used to demonstrate that NMT expansion has a favorable impact on motorized traffic levels and helps to limit the increase in GHG emissions without negatively affecting generalized transport costs (i.e. time and operating costs) and mobility. A model has been developed to estimate the components modal shifts, emissions impact and local benefits, based on current and future transport projections. The monitoring and evaluation activities of the GEF alternative will provide the data to establish and apply an alternative and more comprehensive methodology for the economic analysis of transport operations in general, and in the components that support NMT modes in particular.

3. GEF Strategic Context

The Non-Motorized Transport component of the MMURTRIP project was proposed by the Department of Public Works, Urban Roads Project Office and subsequently endorsed by the Mayor of the City of Marikina in a request to the World Bank for assistance with GEF funding for incremental cost. A strategic choice was made to limit the bicycle network intervention to one city and use this for purposes of cost effectiveness and maximum demonstration effect. Since political commitment is crucial for the success of such initiatives, the City of Marikina has been chosen in view of the fact that the current administration demonstrated and continues to demonstrate exceptional commitment to NMT and to the related environmental issues.

4. Incremental Cost Analysis

Base Case Scenario

Although the anticipated MMURTRIP components to be implemented within the City of Marikina take into consideration modal integration and environmental and safety hazards, they do not specifically address NMT. Moreover the current city transport development plan does not include any investment in bikeways or other NMT facilities. Therefore, without GEF support to

2-3 remove the barriers that hinder the promotion of NMT and the development of adequate facilities to encourage bicycle use, the modal choice pattern will follow very closely the present motor vehicle dominated modal composition experienced in the inner residential districts of Manila. By 2015, the combined effect of increased transport demand and modal split changes in favor of motorized transport will sharply increase congestion and pollution, and will in all probability force the disappearance of bicycles and other forms of NMT. Car/Utility vehicles trips are forecast to increase from the actual average of 53,000 trips per day to more than 120,000. Walking trips are expected to drop significantly, with more pedestrians choosing to use semi-public modes such as taxis or private buses or jeepneys, which will further contribute to o increase the traffic congestion in the area. In the base case scenario, the daily emissions of GHG are forecast to almost double, reaching about 1 million tons of CO2. This will happen even under the assumption of a significant improvement of the average fuel efficiency of the motorized vehicle fleet and of a more efficient utilization of public transport. GEF Alternative Case The GEF grant and the contribution of the City of Marikina will fund the development of bikeways and related facilities designated for NMT Pilot component in the City of Marikina. This component will consist of the following parts: 49.7 km of bikeways on existing roads; 16.6 km of bikeways along the Marikina river banks serving as connection to the new LRT station; traffic calming and pedestrianisation around schools and market areas and provision of bicycle parking facilities; street lighting where necessary to ensure safety after hours; public awareness campaign; bicycle safety program.

The 66 km bikeway network will connect residential communities with schools, employment centers, the new Light Rail Transit (LRT) station and other public transport terminals. On all the sections and main attractions of the bikeways system road/surface markings will be traced, signs placed and parking and safety facilities installed. A series of pedestrianised areas and traffic calming measures will increase the safety of the bikeway network and will also contribute to preserve walking trips. Street lighting in some areas will improve safety of both bikers and walkers. A campaign of public awareness will be launched by the City Administration. The campaign will commence at the preparation stage and will continue throughout the development of the project, including a monitoring component. Its aim is to promote the use of bicycles and other NMT and at the same time receive feedback from the users. A safety campaign will be launched focusing on sensitizing the motorized vehicle drivers and encouraging them to respect bikers and other NMT users. The incremental cost of the component is estimated at US$ 1.8 million of which US$ 1.7 financed by the GEF grant. The City of Marikina will finance the US$ 0.1 million counterpart funds.

2-4 The development of the GEF supported component will help the removal of barriers to the use of bicycles and other NMT modes. The City Administration will consider NMT in its future transport policy and will give priority to the integration of bicycles with public transportation. NMT users will have a safe and efficient system for mobility over short and medium distances. Therefore, the “crowding-out” phenomena mentioned above will be avoided. Moreover the parking facilities and the connections with the public transport terminals will in fact promote the use of NMT combined with LRT/bus for trips between Marikina and the rest of the metropolitan area. With the implementation of the GEF supported component, the modal choice pattern is expected to shift from the one experienced in the inner district of Metro Manila - as well as in many Asian cities – where NMT shares are declining or disappearing. The NMT modes will maintain or increase their quota, as well as public transport on LRT/Bus. Many trips by car outside the area will be avoided as well as the use of jeepneys over short medium distances. This will contribute to the reduction of the congestion and, together with other traffic calming measures will make NMT even more attractive, thus triggering a virtuous cycle, which will be exportable to other areas of Metro Manila, or to other medium cities in the Philippines and abroad. Global Benefits By 2015, the daily emissions of GHG in the GEF Case scenario are forecast to increase substantially less than under the Base Case scenario. With some reasonable assumptions, the savings in GHG emissions (only for the City of Marikina) are estimated to be in the order of 100 tons of CO2 equivalent per day. Assuming an economic life of the project of 20 year (2001-2020) and a linear increase of transport demand during the first 15 years the GHG savings of have been estimated in about 400 thousand tons of C02 equivalent. The details of the estimation of the global benefits are illustrated in Annex 4a. These estimates will be further refined during the final design and preparation of the project. They will monitored monthly, assessed annually and thoroughly evaluated after the first five years of its life. Periodic monitoring and evaluation of its impacts will be conducted by Marikina city after this initial five year period. Local Environmental Benefits In the GEF case scenario, additional local benefit will result from the reduction of motor vehicle pollutants other than GHGs, leading to lower ambient levels of pollution in the project area. These pollutants include oxides of sulfur (SOx), lead, benzene, and ethylene. The component’s local environment benefits will be monitored annually for five years and evaluated at the end of this period.

2-5 Incremental Cost Matrix The incremental cost analysis can thus be summarized as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Incremental Cost Matrix

Base Case GEF Case Increment Description Due to increase of Actual quota of NMT will be N/A motorized traffic and maintained or increased. congestion the use of NMT will decline and eventually fade away by 2015. Global None Reduction of GHG emissions N/A Environment estimated in about 400,000 Benefit tons of CO2 equivalent during the life-span of the project (20 years). Local None Reduction of motor vehicle N/A Environment produced pollutants other Benefits than GHGs leading to lower ambient levels of pollution in the project area. Indirect None Demonstration of NMT as a N/A Benefit sustainable, non-polluting and inexpensive form of transportation, and as a viable alternative for commuting, thus inducing the development of similar facilities elsewhere in the Philippines and in other Countries. Costs 0 US$ 1,821,000 US$ 1,821,000

2-6 Annex 2a: Estimation of the benefits deriving from the savings in GHG emissions resulting from the development of the Marikina City Bikeways Project

1. Background Growth in population, employment and scholastic enrollment will increase both inter and intra-zonal transport demand in the city of Marikina. The increased demand coupled with increased car ownership will boost Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions unless alternative measures to control these emissions are developed and successfully implemented at an early stage. The Marikina Bikeways Project (MBP) supported by the GEF will help to contain the increase of emissions by promoting the shift of the newly generated transport demand towards less polluting modes. To help evaluate the feasibility of the project an analysis of the emissions has been carried out. The objective of the analysis is to estimate the global benefits in terms of GHG emissions reduction through the GEF project implementation. The reduction is computed by comparing the level of emissions in the two different scenarios of (i) Baseline or business-as- usual situation and (ii) a situation in which the MBP is implemented. GHG emissions reduction is calculated by applying the ASIF methodology (Schipper, L. and Céline Marie-Lilliu, 1998. Transportation and CO2 Emissions: Flexing the Link. A Path for the World Bank, draft paper, World bank, Washington DC, 1998) . This methodology allows to estimate GHG emissions by analyzing the following four components: (i) transportation Activity (A); (ii) modal Shares (S); (iii) energy Intensity (I) of each mode; (iv) and the Fuel (F) mix of each mode with its GHG emissions characteristics. In this particular application of the methodology, a transport simulation model based on traffic data from recent studies and on a simple set of assumptions has been developed for the City of Marikina and the broader metropolitan area of Manila. The simulation estimates future Activities and modal Shares in terms of transport demand, vehicle trips, and average distance by mode. The estimates are combined with the relevant values for energy Intensity and fuel Mix of each mode. As a result, approximate levels of transport-generated GHG emissions are obtained. By varying the set of assumptions while simulating the GEF and the Base case the model allows to perform some sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of the findings. Moreover, the last section describes an attempt to evaluate the benefits in terms of reduced levels of Global Warming Damage (GWD) as expected in the framework of the global overlays assessment approach. (Halsnaes K. Markandya A. and Sathaye J., Transport and the Global environment: Global Overlays for the Transportation Sector, draft report, World Bank, Washington DC, 1999) This annex describes the details of the analysis, the simulation model, and the underlying assumptions. A flow diagram that illustrates the factors used in the model and their relationships is presented in (Figure 1).

2a-1 Figure 1 – Flow Diagram of the Model

GLOBAL WARMING COSTS [$]

Global Warming Potential Global Warming Damage (GWP) Equivalent Factors Equivalent Factors [Kg of pollutant = KG CO2] [Kg of CO2 = $]

Intensity TOTAL GHG EMISSIONS and [Kg] Fuel Mix

Average Distance GHG Emission by mode Factors by Mode [Km] [Kg/Km ]

Average Travel Time by mode [h]

Average Speed Fuel Efficiency by by mode Mode [Km/h] [Km/l]

MODAL SHARE Share [Vehicle Trips by Mode]

Modal Split Occupancy Factors [Person Trips by Mode] [Person/Veh.]

TRANSPORTATION DEMAND Activity [No. of Person Trips]

Mobility Demand [Trips/Person]

POPULATION

2a-2 2. Forecast of Travel Demand to estimate the Activity (A) Population Growth The metropolitan area of Manila has been growing rapidly. Its population of less than 2 million in 1950 has increased to 5.9 million in 1980 and 9.5 million in 1995. Total population today is estimated to be above 10 million. This increase in population has been coupled with an expansion of the urbanized area, which today has reached about 800 Km2, far exceeding the 636 Km2 of the metropolitan administrative area or Metro Manila (MM). Total population of the broad metropolitan area, including the adjoining urbanized areas, is about 16 million today. Population growth is expected to continue and the total population of the wide metropolitan area will reach 25 million by 2015, of which about 13 million dwelling in MM and 12 million in the adjoining areas. As Manila becomes more and more densely populated, commercial developments intensify and the living environment degrades further. Land-use in the central areas, once very densely inhabited, gradually changes. Dwellers move to outer areas while commercial/business developments take their place. Manila has been experiencing this movement since the 1980s. The number of trips and trip distances will increase, with more households opting to live outside the inner area, and with jobs and school getting farther away. The City of Marikina, situated at the eastern border of MM, exhibits all the features of this urbanization trend. Its population between 1980-1995 has been increasing at a faster pace then the MM average. The following table (Table 1) summarizes the expected trends in population.

Table 1 - Trends in Population Area No. ('000) Avg. Growth 1995- 2015 (% per year) 1995 2000 2015 Metro Manila (excl. Marikina) 9,097 9,897 12,744 1.7% Adjoining Areas 4,914 6,212 12,550 4.8% Marikina 357 418 670 3.2% Source: NSO and City of Marikina

Trends in Passenger Travel Demand Population growth is associated with an increased demand for mobility, both within Marikina administrative borders and to and from central and other districts of Manila. Changes in the social composition and in car ownership ratio, which tend to level to the values for the inner urbanized areas, contribute to further amplify the upward trends. In 2015 the population of the City of Marikina is expected to be 5.1% of the population of MM, up from 3.8% in 1996. Total travel demand for Marikina is expected to be about 6% of the total demand generated in the Metro Manila area, up from only 2.8% in 1995. As outlined in the table below (Table 2), between 1995 and 2015, the compounded effect of increased population

2a-3 and mobility will result in a 4.7% yearly growth rate of passenger travel demand generated in Marikina, expressed in Passenger Trips per Day. These figures are based on the estimates of the Metro Manila Urban Transport Improvement Study (MMUTIS), an on-going study which provides in its data bases detailed travel demand figures by Origin and Destination for the broader metropolitan area.

Table 2 – Expected Passenger Travel Demand Area No. of Passenger Trips per Day Avg. Growth 1995-2015 ('000) (% per year) 1995 2000 2015 Metro Manila (excl. Marikina) 17,258 18,925 22,367 1.2% Adjoining Areas 6,842 8,697 18,845 5.2% Marikina 496 710 1,274 4.7% Source: Project Team Elaboration based on MMUTIS data.