VA Takes the Lead in Paperless Care Computerized Medical Records Promise Lower Costs and Better Treatment By David Brown Washington Post Staff Writer Tuesday, April 10, 2007; Page HE01

Divya Shroff, a staff physician at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Northwest Washington, stops what she's doing to answer her phone: It's a doctor down the hall who needs help with a man struggling to breathe.

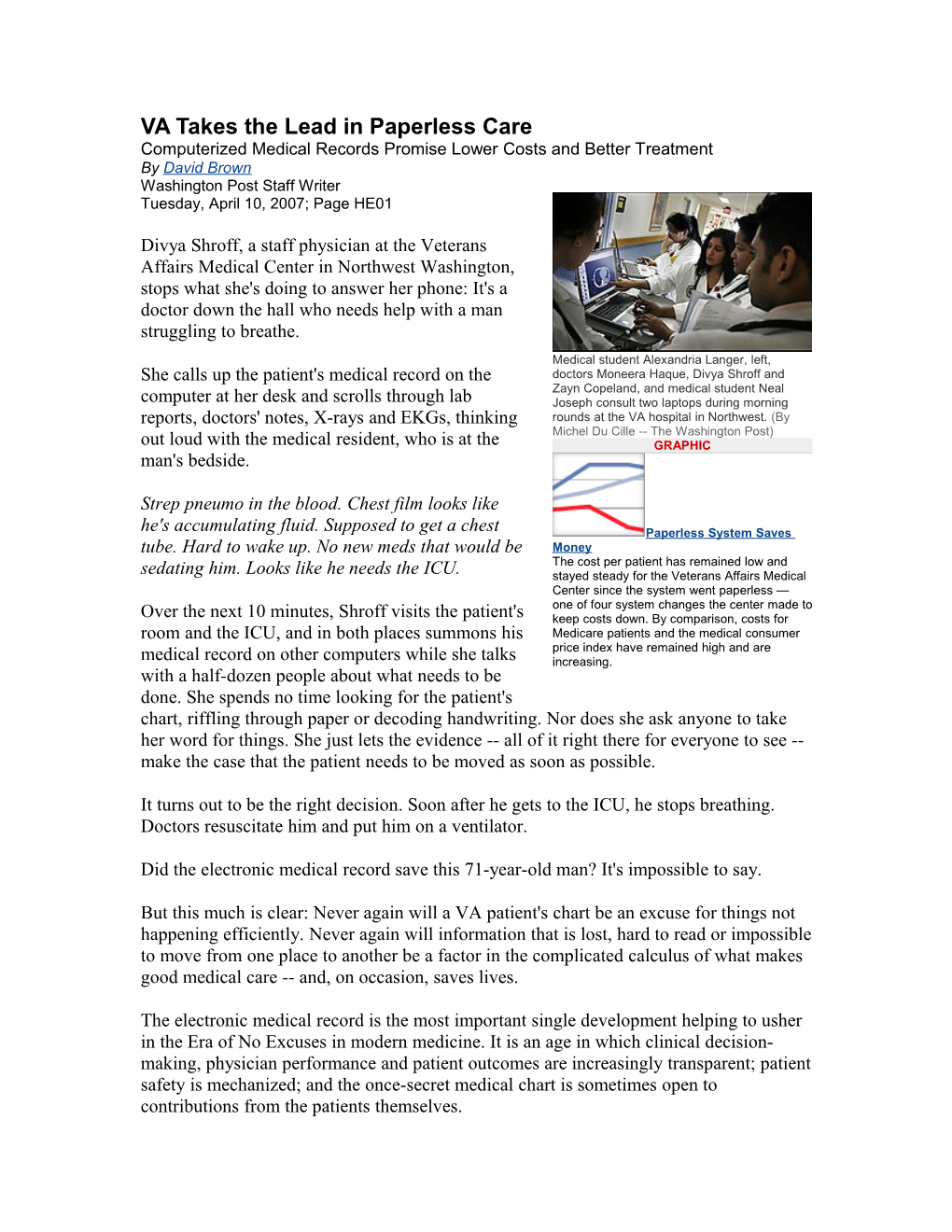

Medical student Alexandria Langer, left, She calls up the patient's medical record on the doctors Moneera Haque, Divya Shroff and Zayn Copeland, and medical student Neal computer at her desk and scrolls through lab Joseph consult two laptops during morning reports, doctors' notes, X-rays and EKGs, thinking rounds at the VA hospital in Northwest. (By Michel Du Cille -- The Washington Post) out loud with the medical resident, who is at the GRAPHIC man's bedside.

Strep pneumo in the blood. Chest film looks like he's accumulating fluid. Supposed to get a chest Paperless System Saves tube. Hard to wake up. No new meds that would be Money The cost per patient has remained low and sedating him. Looks like he needs the ICU. stayed steady for the Veterans Affairs Medical Center since the system went paperless — one of four system changes the center made to Over the next 10 minutes, Shroff visits the patient's keep costs down. By comparison, costs for room and the ICU, and in both places summons his Medicare patients and the medical consumer price index have remained high and are medical record on other computers while she talks increasing. with a half-dozen people about what needs to be done. She spends no time looking for the patient's chart, riffling through paper or decoding handwriting. Nor does she ask anyone to take her word for things. She just lets the evidence -- all of it right there for everyone to see -- make the case that the patient needs to be moved as soon as possible.

It turns out to be the right decision. Soon after he gets to the ICU, he stops breathing. Doctors resuscitate him and put him on a ventilator.

Did the electronic medical record save this 71-year-old man? It's impossible to say.

But this much is clear: Never again will a VA patient's chart be an excuse for things not happening efficiently. Never again will information that is lost, hard to read or impossible to move from one place to another be a factor in the complicated calculus of what makes good medical care -- and, on occasion, saves lives.

The electronic medical record is the most important single development helping to usher in the Era of No Excuses in modern medicine. It is an age in which clinical decision- making, physician performance and patient outcomes are increasingly transparent; patient safety is mechanized; and the once-secret medical chart is sometimes open to contributions from the patients themselves. Electronic medical records make confusing and physically unwieldy masses of data instantly available, portable and searchable -- altogether more useful than when the information was stored on paper. Computer-accessible records have the potential to save the cost-strangled American medical system billions of dollars in waste, repetition and error. They may also prove to be essential tools of research, allowing scientists to examine patterns of medical practice, drug use, complication rates and health outcomes.

Since 1999, the VA's 155 hospitals, 881 clinics, 135 nursing homes and 45 rehabilitation centers have been linked by a universal medical records network. It allows any authorized person to look at 5.3 million patients' records -- everything from a nurse's note written during a hospital stay, to the result of a blood test drawn at a clinic visit, to the moving- picture film of a coronary angiogram done in a cardiology lab.

Even though President Bush has set a goal of 2014 for when most Americans should have their medical information stored electronically, the Department of Veterans Affairs is today one of the few health systems -- and by far the largest -- that is virtually paperless.

A study commissioned by the Department of Health and Human Services last fall reported that one-quarter of American physicians use some sort of electronic record- keeping in their practices. But less than 10 percent have systems that store all necessary data, allow electronic ordering of tests and provide clinical reminders. Only 5 percent of the country's 6,000 hospitals have computerized ordering of drugs and tests, and even fewer have a fully integrated system like the VA's.

Although some people believe making medical records widely available to many practitioners is a threat to privacy, VA officials believe strongly that patient privacy is more secure now than in the era of paper charts.

In the past 2 1/2 years, the VA has investigated 20 complaints of security breaches. Seventeen were for patient records accessed by unauthorized people, and three were for release of medical data to third parties without patient consent, VA spokeswoman Jo Schuda said.

The Problems of Paper

In the popular mind, the chief deficit in medical records is legible handwriting. But that doesn't begin to describe the problem.

Many hospitals have multiple paper charts for each patient -- one for hospital stays, another for clinic visits and others for specialty services such as physical therapy. Information is passed via carbons, faxes and letters.

The charts themselves are often maddening arrays of paper held together with metal tabs and wheeled in groups by shopping cart from file room to consultation room. (Before the VA got its electronic system, only 60 percent of patients' charts could be found on any given visit.) Looking at X-rays and imaging scans is equally inconvenient and unpredictable, requiring trips to a film library and luck that the right folder can be retrieved.

Electronic medical records eliminate those headaches. But they do less obvious things, too.

Searchable computerized databases allow physicians to examine information collected across time and space. (In the case of the VA, a doctor in Washington can easily find a blood test from a patient treated five years ago at the San Francisco veterans hospital.) The ability to detect trends in physiological variables such as serum chemistry, cell counts, blood pressure and even weight is important to good decision-making. But it is often hard to do. Electronic medical records make it easier.

Electronic record systems also bridge one of the more perilous chasms in medicine: the transfer of care when patients leave the hospital.

Two years ago, a study of 2,600 patients discharged from university hospitals found that 41 percent had test results pending when they left. One in 10 of those tests eventually proved abnormal enough to warrant action -- more testing, a new diagnosis or a change in treatment. However, other research has shown that up to 85 percent of patients visit their primary care doctors -- who these days are likely to have had little if any role in their hospital care -- before a summary of their last hospitalization arrives.

This discontinuity is a well-recognized hazard. A 2003 study showed that 49 percent of patients suffered at least one medical error in the two months after leaving the hospital, often because the outside doctors didn't know what was done in the hospital, or what was left to do.

Such problems are much less likely when everyone has the same information and nobody has to remember to deliver it.

Electronic records are especially helpful in managing prescription drugs, a major source of medical errors. The VA software flags questionable doses and potential interactions. Hospitalized patients have bar codes on their wristbands that are scanned for an identity check each time a pill is dispensed or an injection given.

The VA dispenses 240 million outpatient prescriptions a year. The computer system tells practitioners not only what a patient has been prescribed but what he has actually picked up from the pharmacy.

The value of such a database became clear after Hurricane Katrina, when 560 people were evacuated from the Armed Forces Retirement Home in Gulfport, Miss., and brought to Washington. "Their medical records were floating in the Gulf somewhere," said Sanford Garfunkel, the 59-year-old administrator of the Washington VA hospital. "But those veterans who had been seen by the VA, we could access their records. We filled 1,800 prescriptions literally overnight."

The VA is now rolling out "My Health e Vet," a feature that allows patients to create a portal to their own charts, where they can record measurements they take at home (weight, pulse, blood sugar, blood pressure); list over-the-counter medicines they use; and offer comments about their health.

"It's a little like MySpace," said Joel Kupersmith, former dean of the Texas Tech University School of Medicine and now the VA's chief research and development officer, referring to the social networking Web site. "The patient will have his own little corner in the record where he can keep his own data. That is a revolution in medicine, as far as I know."

Electronic records can also improve physician performance. They can warn of things that shouldn't be done, provide reminders of what should be done and monitor what is done.

A study published in 2004 compared the care of VA and non-VA patients in 12 communities, using 348 quality indicators as the yardstick. VA patients scored higher on overall quality, chronic disease care and preventive care.

Electronic records appear to be money-saving devices, at least in some hands. By one estimate, they could save American medical care $162 billion a year. Many hospital systems, however, balk at the upfront investment, which can range from "a few million to 50 to 60 million dollars," said Pat Wise, an executive with Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, a trade and professional organization.

The cost of the VA's electronic medical record, called VistA (for Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture), is hard to measure. It was developed over many years by many people, including hundreds of clinicians. However, the software is now free to anyone who wants to get it through the Freedom of Information Act.

Places where versions are in use include the U.S. Public Health Service's Indian Health Service; the Berlin Heart Institute in Germany; and Nasser Institute Hospital in Egypt. Mexico is adapting it for its entire health system.

A Wireless Team

To most patients in VA hospitals, the electronic medical record is essentially invisible. But to the practitioners and their students, it is an ever-present problem-solver, clinical resource and educational tool. This is evident when Divya Shroff's team of one resident, two interns and two medical students does morning rounds with two wireless laptops on wheeled carts. On one they order lab tests, diets, drugs, dosage changes, X-rays, scans and specialist consultations. Most are entered as soon as they leave the patient's room, a strategy that gets the tasks underway earlier than when orders traveled by foot or pneumatic tube.

The team uses the other computer for teaching, such as when the group gathers outside the door of Harold W. Bazel, a 71-year-old retired Army staff sergeant.

Shroff uses the computer to chart two episodes of sudden decline in Bazel's hematocrit -- the fraction of his blood that is made up of red cells. She calls up the analysis of fluid recently sampled from a large pocket around his left lung. She helps the medical students figure out that a lot of the "missing" blood must be there. She scrolls through the slices of his chest CAT scan, pointing out worrisome densities. The group together makes a plan for how to proceed with a diagnostic workup that it hopes will reveal what is happening inside Bazel's chest. They all then step into his room.

He is sitting on the bed in burgundy VA-issue pajamas. Members of the team ask to listen to his chest. They explain the next study they are ordering and discuss possible results.

"I'm beginning to think you haven't figured out what it is yet," he says.

"Well, we're working on it," Shroff says, and pats his forearm. The team leaves, retrieves the computer carts it has left in the corridor and heads off to its next stop.

If the computerized record is an invisible presence to many patients in the hospital, it is an unavoidable one to patients outside it.

"The computer is reminding me that once a year we need to check your feet," Melissa Turner, an internist who works in the outpatient clinic attached to the hospital. She is speaking to 66-year-old William Torney of Clinton while looking at the monitor on her desk.

Torney is a diabetic. The medical record knows this. It also knows that studies have shown that periodic examination of diabetics' feet helps practitioners catch amputation- inducing sores when they are small and treatable. The computer won't stop reminding Turner to check Torney's feet until she does it and charts it.

He takes off his socks. One at a time, she takes a foot on her knee and examines it. There are no sores, but the pulses are weak, a sign of poor blood flow that can make wounds hard to heal. Turner concludes it's probably not the best idea to have her patient cut his toenails and risk nicking himself.

"I'm going to ask the podiatrists to see you," she says, adding her findings to the computerized note of this clinic visit. Automated, to a Point

Down the corridor, Neil Evans, 34, is between patients.

Evans is a technophile and a big fan of the computerized record. He is also a very busy man. He commutes from Baltimore -- by bicycle, train and subway -- nearly four hours a day and has a set of young twins at home. Efficiency is a priority, and he uses the computer to maximize it.

He's acutely aware, though, of the hazard of having a machine between the doctor and the patient.

"If you spend your entire time looking at the screen, it is going to affect the patient's perception of quality -- and I think it ultimately affects the care you can deliver the patient," he says. He knows that at least part of his success depends on simple human contact. "People don't stop smoking because I tell them to," he adds. "They stop smoking because they respect my opinion, they know me."

Consequently, he tries to use the machine as a tool of engagement, not a barrier.

When he is interviewing a patient, he periodically stops for a machine-gun burst of typing, during which he repeats out loud what he is writing -- a kind of verbal spell- check. He occasionally turns the monitor to show the patient a graph or an image. He ignores the computer during the most important parts of the conversation.

"They know they are going to lose some of my attention, but in the end get more information," he says.

When he sees his next patient, Randy Melvin Brown, 56, Evans spends about half the time leaning forward, forearms on his knees, as Brown describes the searing pain in his legs. It is probably a side effect of chemotherapy he is getting for a blood cancer called multiple myeloma.

Brown won a Bronze Star in Vietnam. His face bears a long scar from an encounter with barbed wire on a fire base there. He is on a complicated regimen of painkillers and neurological drugs. His eyes fill with tears as he describes how they aren't working.

The ubiquity of computers at the VA, where Brown now spends much of his time, has not escaped him. It doesn't bother him.

"From my point of view, I would say it's good," he says of the use of computers by Evans and other doctors. "Sometimes I forget what I'm getting into. I'll go back to him and bring it up, and he'll find it because he's got it in his computer." Evans types for a few minutes, then faces Brown again to propose a plan. He is going to refer him to a special clinic for people with severe or chronic pain. To tide him over until then, he is going to prescribe a much higher dose of opiates.

Evans swivels back to the computer. At the VA, prescriptions for such drugs require that a patient's name, address and Social Security number be written on paper and signed by hand.

Evans has programmed his computer with a template that allows him to paste in the required information and send it to a printer next to his desk.

"This is what happens when you start using the electronic medical record," he says, peeling off a blank script and putting it in the printer tray. "When you have to do something archaic like write a prescription, it just drives you bananas."

He pushes a button, and in a few seconds the prescription pops out. Even the "no refills" option on it has been magically circled. He signs it. It's the first time he's used a pen in 20 minutes. ·

Comments:[email protected].