Nasoseptal perforations (BJPS 2000 + PRS 1999)

Causes 1. Iatrogenic . septal surgery (usually Killian SMR) – most common . cautery for epistaxis, and nasal intubation 2. Cocaine 3. intranasal trauma 4. systemic diseases (Wegeners, SLE) 5. infections (syphilis and tuberculosis) 6. inhalation of irritant substances 7. malignant conditions 8. very rarely, congenital perforation. Perforation rates of 17–25% have been reported following submucous resection and 1.4–5% after septoplasty.

Symptoms crusting and bleeding from the hypertrophied mucosa at the margins of the perforation dryness, discomfort, odour and alterations of smell. Small perforations sometimes cause whistling. Very large perforations may result in loss of dorsal support and deformity of the external nose. Most symptomatic perforations are large and involve the anterior cartilaginous portion of the septum; posterior perforations tend to be less symptomatic because of the rapid humidification of the inspired air by the nasal mucosal lining and turbinates.

Classification (1) asymptomatic- Posterior perforations and perforations with well healed edges. (2) small symptomatic (less than 2.0 cm) (3) large symptomatic (greater than 2.0 cm)

Management: generally agreed that there is no point in attempting to treat an asymptomatic perforation.

Conservative ointments and nasal saline sprays to soften crusts obturator – o method of choice when the cause of the perforation cannot be eliminated, for example, active and ongoing systemic disease. o can reduce whistling and bleeding o increase mucus production and encourage crust formation

Surgical gold standard possible for the majority of small (under 2 cm diameter) perforations. Requirements 1. lining for the nasal cavities 2. a supporting layer.

Centralise septum Whistling is diminished with a straight septum

Intranasal mucosal flaps( mucoperichondrium and mucoperiosteum flaps) rotation or transposition flaps only suitable for small perforations, and tends to develop suture dehiscence. inferior turbinate flap unreliable and difficult. 2 staged procedure – complications include nasal obstruction due to the thickness of the graft, and disruption of the alae. bipedicled mucoperichondrial advancement flaps. o mucoperichondrium is dissected from the cartilaginous and bony septum, the floor and roof of the nose, and even the turbinates if necessary. o success rates for this method have been improved by using bilateral (rather than unilateral) mucosal flaps, and by combining them with an interposed autogenous connective tissue graft. o The main limitation is that it is unacceptable to leave both sides of the septum bare of mucosa at any point because reperforation will occur. o This limits the size of perforation to less than 4 cm diameter. bilateral, posteriorly based, unipedicled, intranasal mucosal flaps (Romo PRS 1999) o extended external rhinoplasty approach

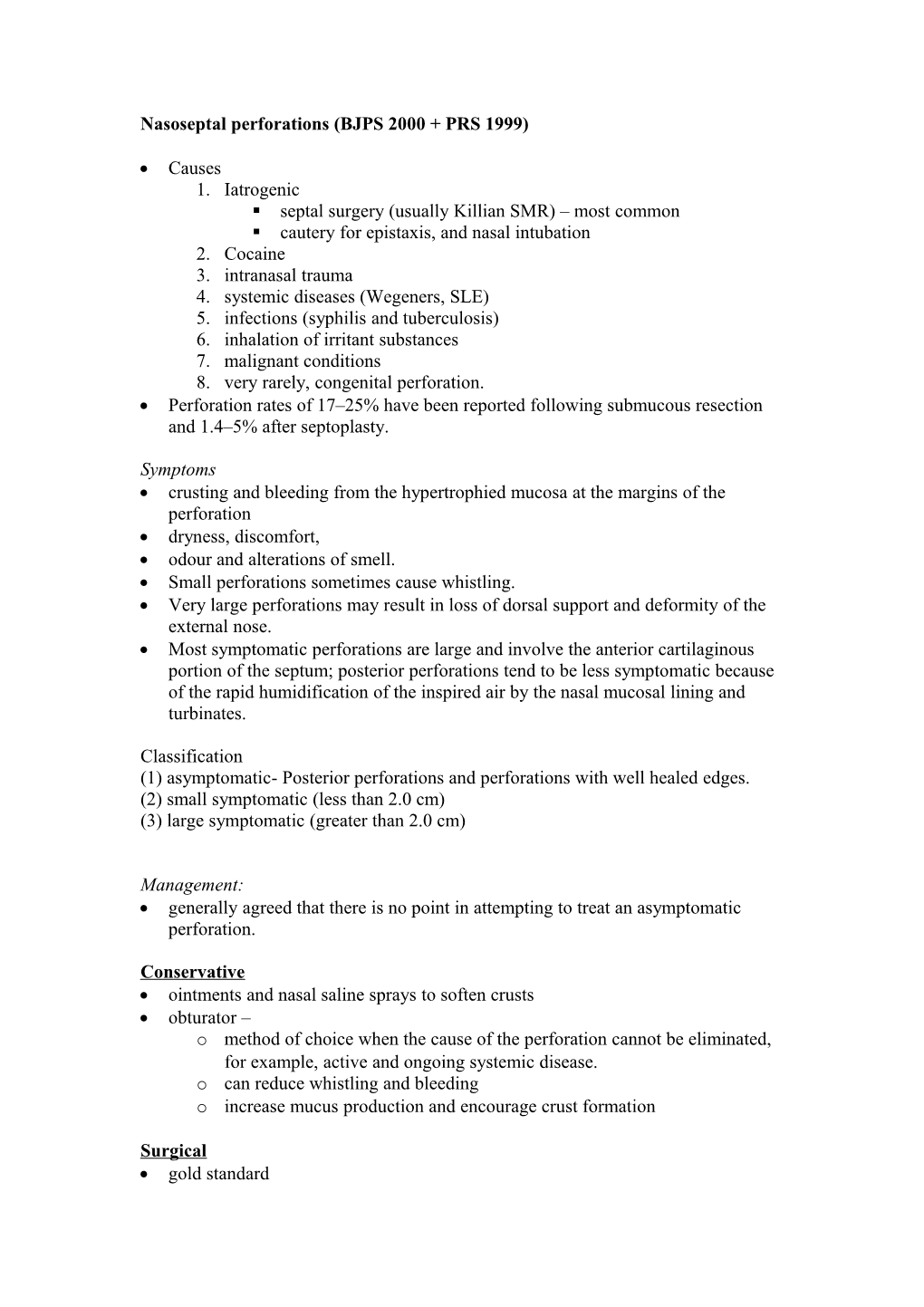

A, full transfixion incision; B, transcolumellar incision; C, septal perforation.

S

S

Exposure of nasal septal perforation using the extended external rhinoplasty approach. A, columella flap retracted; B, cartilaginous perforation; C, mucosal perforation; D, mucosa elevated and reflected laterally. Bilateral closure of mucosal flaps with an interposition graft of acellular dermal graft (Alloderm). A, Alloderm dermal matrix covering septal perforation; B, mucosal perforation closed with interrupted sutures.

Completion of flap elevation rotation and repair of perforation. A, middle turbinate; B, posterior naris; C, inferior turbinate infractured; D, raw surface area left by flap rotation; E, full-thickness skin graft on floor of nose; F, rotated flap; G, anterior septal angle.

Connective tissue autografts

perforations heal more reliably if a support is provided which can act as a substrate for re-epithelialisation if part of the mucosal flap fails, or the mucosa does not completely cover the perforation on both sides Flaps of mucosa alone are prone to suture dehiscence, even when constructed bilaterally. small perforations – local septal cartilage or bone o if take too much, weakens external support Other options: autografts: temporalis fascia with cranial periosteum as well when a thicker graft is required; mastoid periosteum; bone from the vomer, ethmoid or iliac crest; and auricular or rib cartilage. best choice of autogenous connective tissue graft is temporalis fascia.

Large defects some authors use obturators for all perforations >4cm options o nasolabial flap (Millard PRS 2002) o labial-buccal flap o FAMM Flap (Ann Plast Surg Nov 2005) . Superiorly based . full-thickness skin graft used to line the raw side . May be complicated by oronasal fistula

o perichondrocutaneous graft harvested from the anterior part of the auricular concha o prefabricated labial-buccal flap (with support graft) (Meyer 1994) o 1x3cm intranasal tissue expander into a submucoperiosteal pocket in the nasal floor unilateral or bilateral) – Romo PRS 1999 . 2 stage approach incision used for midfacial degloving. A, intercartilaginous incision; B, septal perforation; C, complete transfixion incision; D, nasal floor sill incision; E, gingivobuccal incision.

o radial forearm free flap

o pericranial flap