p.1

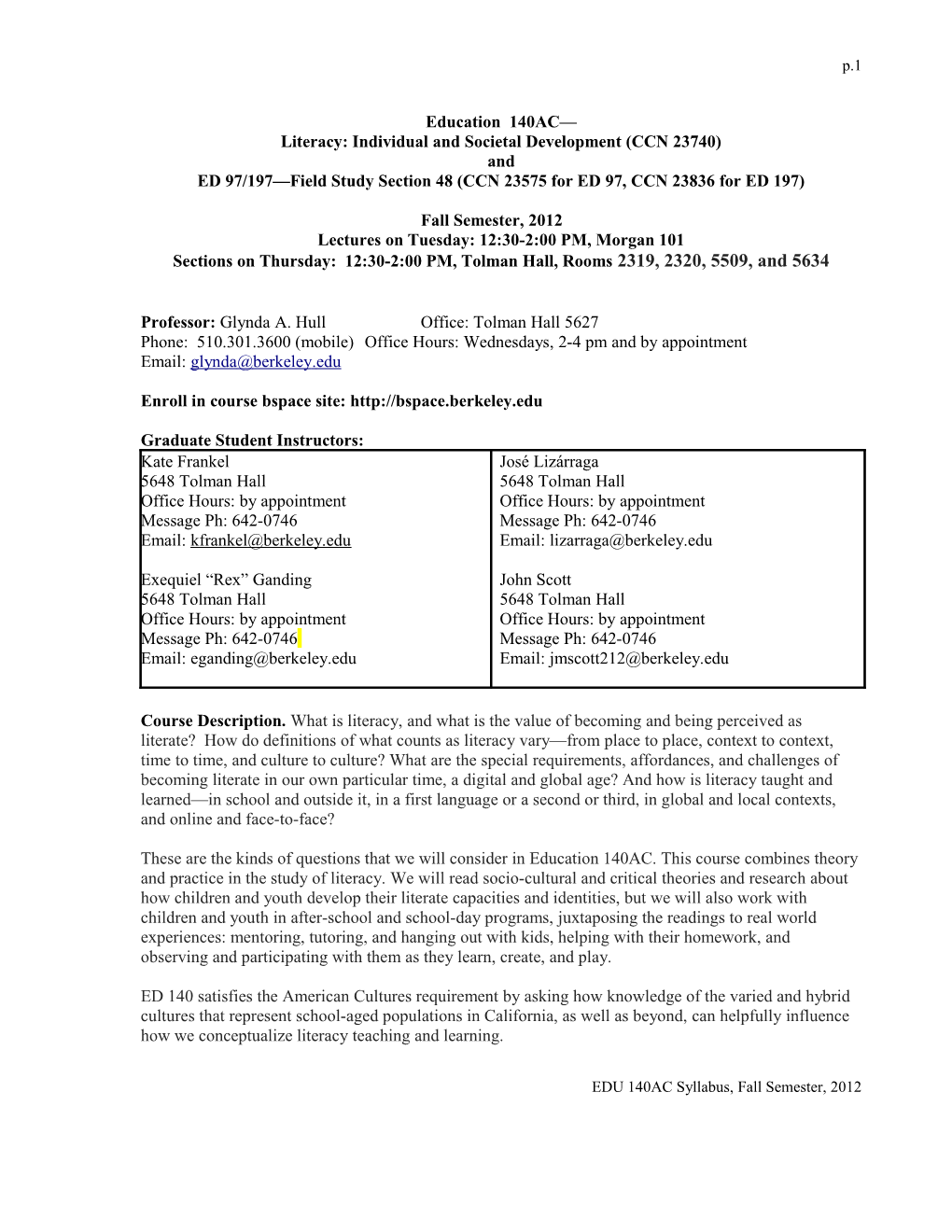

Education 140AC— Literacy: Individual and Societal Development (CCN 23740) and ED 97/197—Field Study Section 48 (CCN 23575 for ED 97, CCN 23836 for ED 197)

Fall Semester, 2012 Lectures on Tuesday: 12:30-2:00 PM, Morgan 101 Sections on Thursday: 12:30-2:00 PM, Tolman Hall, Rooms 2319, 2320, 5509, and 5634

Professor: Glynda A. Hull Office: Tolman Hall 5627 Phone: 510.301.3600 (mobile) Office Hours: Wednesdays, 2-4 pm and by appointment Email: glynda @ berkeley .edu

Enroll in course bspace site: http://bspace.berkeley.edu

Graduate Student Instructors: Kate Frankel José Lizárraga 5648 Tolman Hall 5648 Tolman Hall Office Hours: by appointment Office Hours: by appointment Message Ph: 642-0746 Message Ph: 642-0746 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected]

Exequiel “Rex” Ganding John Scott 5648 Tolman Hall 5648 Tolman Hall Office Hours: by appointment Office Hours: by appointment Message Ph: 642-0746 Message Ph: 642-0746 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected]

Course Description. What is literacy, and what is the value of becoming and being perceived as literate? How do definitions of what counts as literacy vary—from place to place, context to context, time to time, and culture to culture? What are the special requirements, affordances, and challenges of becoming literate in our own particular time, a digital and global age? And how is literacy taught and learned—in school and outside it, in a first language or a second or third, in global and local contexts, and online and face-to-face?

These are the kinds of questions that we will consider in Education 140AC. This course combines theory and practice in the study of literacy. We will read socio-cultural and critical theories and research about how children and youth develop their literate capacities and identities, but we will also work with children and youth in after-school and school-day programs, juxtaposing the readings to real world experiences: mentoring, tutoring, and hanging out with kids, helping with their homework, and observing and participating with them as they learn, create, and play.

ED 140 satisfies the American Cultures requirement by asking how knowledge of the varied and hybrid cultures that represent school-aged populations in California, as well as beyond, can helpfully influence how we conceptualize literacy teaching and learning.

EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.2

Course Organization. Unless otherwise announced, we will meet every Tuesday in Morgan 101 for lecture. Beginning on Thursday, August 30 (class 3), unless otherwise announced, we will meet as sections in Tolman Hall. The class will be divided into 4 sections, which will correspond to your fieldwork sites (see below). These sections will be lead by Graduate Student Instructors. You will learn your section room and GSI the second week of class, once decisions have been made about fieldwork sites.

Field Work Component (Ed 97/197: Section 48—CCN 23575 for ED 97, CCN 23836 for ED 197). Students will complete 45 hours of field work by volunteering at local after-school sites, which works out to approximately 3-4 hours each week. To receive credit for this field work, you must enroll concurrently in 1-unit of the above listed section of ED 97 (if you are a freshman or sophomore) or 197 (if you are a junior or senior). We have organized field work placements for you at a variety of school sites, including St. Martin de Porres Middle and Elementary Schools, St. Cornelius, St. Elizabeth, St. Anthony, St. Jarlath, Our Lady of the Rosary, and the Oakland Military Institute. Details about these sites—descriptions, directions, hours of operation, etc.—will be provided during Classes 1 and 2 (August 23 & 28). Please plan to do your fieldwork at one of the sites we have organized.

Criminal Background Check Clearance (Fingerprinting) and TB Testing: All students must obtain a criminal background clearance through fingerprinting and provide proof of TB clearance to conduct field work at school sites. Fingerprinting should be coordinated with the school staff at the field work site. TB testing can be done at the Tang Center or other medical facilities. Beginning this school year student health insurance covers 100% of the cost of the TB skin test tests done at Tang. For students with private insurance the cost is $20. Information and hours for testing are posted on the Tang Center website. Your TB test results should be turned in to designated staff at the school.

Transportation to/from sites: We encourage students to organize car pools or to travel together to sites on public transportation. We are able to reimburse your transportation costs with proof of payment (i.e., receipts for public transit and vehicle information if a private vehicle is used) and properly completed campus reimbursement forms. More information and details will be provided in class and on bspace.

Required Course Readings Please purchase a course reader from Replica Copy at 2140 Oxford (549-9991). This reader, which comes in 2 volumes, will be your only required text for the course. Note that there are readings for each week, starting with the second class (8/28) and going through the last week of the semester. Tuesday lectures will introduce the themes for the week, and some of these themes will be discussed in greater depth in Thursday sections.

Course Requirements There are five main activities associated with this course:

1. Regular class attendance and participation—Please expect to attend lectures and sections, and be alert to the fact that excessive absences will affect your final grade. If you miss one class during the first 2 weeks, you will be dropped from the course. After the second week of class, you may be absent 2 times during the semester without your grade being affected. If you are absent more than the allowed number of days, two points per additional absence will be subtracted from your final grade in the course (unless you present legitimate documentation, such as a doctor’s excuse or a letter from your coach, etc.). Here is an example of the grade penalty for excessive absences: A student accumulates 4

EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.3 unexcused absences during the semester. The first 2 do not count against the student. The additional 2 absences will result in 4 points being subtracted from the final course grade.

Please note: A roster will be available each day in class; be sure to sign it to indicate your presence. If you need to miss class, or if you need special accommodations for completing assignments, or if you want us to have emergency medical information, please let Professor Hull or your GSI know.

Lectures will be held on Tuesdays in 101 Morgan. Beginning with Class 3 on Thursday, August 30, we will meet each Thursday in sections. For section meetings we will divide into 4 groups, meeting separately in the lecture hall in Morgan Hall and the following rooms in Tolman Hall: 5509, 2326, 2325, and 2019.

2. Participating in an after-school or school-day program at least three hours a week—In addition to lectures and sections, this course requires participation in an after-school program with children or youth for a total of 45 hours (which comes to approximately 3-4 hours a week). You’ll be selecting or assigned to a field site during the second week of class (8/27-8/31). Visits to sites will also be arranged during the second week of class. Field work will begin the third week of class, 9/3-9/7). Detailed information about the sites and the orientations will be provided in class and/or on bspace.

To receive academic credit for your participation in the after-school program (in addition to the 3 units represented by this course), you will need to enroll concurrently in 1 unit of ED 97/197 (Section 48; CCN 23575 for ED 97, CCN 23836 for ED 197). You may sign up for more units if you desire and your schedule allows. One unit equals three hours of field work per week. (Also, in subsequent semesters, if you want to continue volunteering at the same site, you can do so for credit; contact Prof. Hull at the beginning of the new semester.) Please note that your unit of ED 97/197 counts toward the field work requirement of the Education Minor. ED 140AC students who don't want or need a unit of credit through ED 97/197 don’t have to sign up but are still required to participate in the after-school program for a total of 45 hours over the course of the semester and to keep a record of dates and hours spent participating.

3. Completing reading assignments—The completion of reading assignments will be assessed in section meetings. The GSI in charge of the section will determine the nature of the assessment, but likely possibilities include journals, blogs, quizzes, forums, and/or participation in section discussions. Detailed information on this requirement will be provided at the first section meeting.

4. Completing two writing assignments and one reflection project—a literacy autobiography or biography (due midterm on Friday, 10/19), a case study of some aspect of your field work (due at the end of the semester on Friday, 12/07), and a group performance/presentation of your reflections on the course (presented in class during the last two class meetings on 11/27 and 11/29). The literacy autobiography/biography, the case study, and the reflection project will be explained during class, and the assignments will also be provided via bspace.

5. Submitting detailed field notes (see below)—Field notes will record your experiences at the after- school site.

Grading: Field notes 25% Reading assignments 15%

EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.4

Literacy autobiography 20% Case study 30% Performance reflection project 10% Pass/Fail students: Satisfactory completion of all requirements except the case study.

FIELD NOTE POLICIES Field notes are an important part of qualitative research, serving as a record of your experiences at your field work site this semester and a way for you to reflect on what you are doing and learning this semester. They will also be the primary source of data for your case study project at the end of the semester.

Logistics of submitting field notes Please submit your field notes electronically to your GSI on bspace. (GSI assignments will be made during the second week of class, and you will be given an email address for turning in your field notes then as well.) Files should follow the following naming format: Last name-FN #.doc

Requirements and Due Dates A total of ten field notes are required (although you are welcome to write more). Each field note is due on Fridays by midnight (11:59 PM). Your first field note should be turned in Friday, September 7, by midnight. Each field note should describe field work done the same week. For example, a field note turned in on Friday, September 7 would report field work done during the week of September 3. Collectively, field notes represent 25% of your grade.

Advice Write your field notes AS SOON AS POSSIBLE after you get home from volunteering. You will remember the key details MUCH BETTER than if you wait a day.

Field note and filename headings At the top of your fieldnote, please include your name, your email address, the site, the date, the main activities you took part in, and the names of the people you interacted with. Also, in the filename of your submitted file, please include your name, the date, and the field note number (1-10 to denote how many field notes you’ve submitted). Field notes have three sections, with three corresponding headings (General Observations, Focused Observations, and Reflections). A) General Observations. This section is particularly important at the very beginning of the semester as you become familiar with your volunteer site. In your first field note, give a DETAILED description of your volunteer site and its neighborhood based on your first impressions. Also provide a general description of all the activities you took part in that day. Update the description of the volunteer site (& the neighborhood) as things change or as you notice new things. Every week, give a general description of all the activities you participated in. In this section you are providing a context for the rest of the field notes. This section should be particularly detailed the first day so you can give a good, vivid description of your first impressions. Focus on what you saw & heard (& maybe smelled, touched or tasted!). B) Focused Observations. This will normally be the longest part of each field note (perhaps 2- 3 good paragraphs, but you can write more). For each site visit, pick out the one activity that was most interesting, significant, harrowing, insightful, humorous, etc. Give a DETAILED description of this activity and the people participating (names if possible). Describe the participants' appearance: age, clothing, gestures, hairstyle, mannerisms, etc. Describe exactly what happened, blow by blow. Report anything significant that was said, in as close as possible to the exact words. Again, focus on what you saw & heard (& maybe smelled, touched or tasted!).

EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.5

C) Reflections. Finally, write at least one good detailed paragraph on what you thought and felt about your visit, and especially what happened in the activity described in your Focused Observations section. What did you learn from this activity? If possible, relate (or contrast) your experiences to EDUC 140AC readings from the semester &/or to class or section discussions. We also recommend that you reference your own previous field notes, comparing and contrasting previous visit and insights.

Field Note Grading Make sure you follow the guidelines above, including those related to formatting the field notes. Include lots of vivid, detailed description. Relate your experiences to class readings and discussions in an insightful way. Make sure you include all 3 sections, and that each section is complete. Don't repeat the same insights week after week. Your field notes will be given a letter grade by your assigned GSI and returned to you promptly. Please note that your GSI will comment on your first 3 field notes in detail, making sure that you understand how to write excellent ones. Thereafter, your GSI will read and grade each field note, but will not comment in detail.

RECORD-KEEPING: You’ll find a handy record-keeping/grade-keeping tool on bspace in the Resources folder. You can use it to keep track of your field notes, site hours, and grades.

SCHEDULE OF READINGS

PART I: SETTING THE STAGE

Part 1: Introduction

WEEK 1 (8/23)—Course introduction

WEEK 2 (8/28 and 8/30)—What is the power of literacy, and how do we study it?

Scribner, S. (1988). Literacy in three metaphors. In E.R. Kintgen, B.M. Kroll, & M. Rose (Eds.), Perspectives on literacy (pp. 71-81). Carbondale, IL: Southern READ Illinois University Press. Scribner examines different and conflicting views of literacy's social purposes and values; in so doing, she summarizes her and Michael Cole's research among the Vai people of West Africa.

Rose, M. (1989). "I just wanna be average." In Lives on the boundary: An account of the struggles and achievements of America's educationally underprepared (pp. 11-37). New York: Penguin. Rose writes an evocative account of his years in the "Voc Ed" track, reflecting on his own school experiences in light of public discussions of education and the underprepared student. He also describes how a teacher encouraged him to write and how being a writer became a powerful identity.

Cushman, E. (1998). Selections from The struggle and the tools: Oral and literate strategies in an inner city community. (1-4; 21-32). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. In this selection, Cushman discusses her perspective as a social scientist who believes in conducting socially responsible, respectful, and collaborative research.

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S.K. (1998). Selections from Qualitative research in education: An introduction to theory and methods 3rd edition. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon. (121-129).

EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.6

This reading offers clear advice on how an observer does the nitty-gritty work of turning observations into written text.

Field notes by former 140AC Students: (everyone reads #6; choose one or more in addition): (1) Holly San Miguel, (2) Clara Bosak-Schroeder, (3) Arbella Malik (these first 3 field notes are from Castlemont High School in Oakland); (4) Jennifer Noh (about an adult literacy program); (5) field note (author’s name removed) about digital storytelling program for elementary school children (6) Gilbert Goldenbear (a template with tips on field note formatting and content).

WEEK 3 (9/4 and 9/6)—What is illiteracy, and how might we re-conceive it?

Hull, G., & Rose, M. (1990). “The wooden shack place”: The logic of an unconventional reading. College Composition and Communication, 41(3), 287-298. In this article, Hull & Rose present a case study of a UCLA undergraduate whose interpretation of a poem was viewed by his teacher as “off mark.” Relying on interviews with the student and knowledge of his history and background, they demonstrate what they call the “logic and coherence” of his unconventional reading.

Alim, H. S. (2011). Global Ill-Literacies: Hip Hop Cultures, Youth Identities, and the Politics of Literacy. Review of Research in Education, 35, 120-146. This article turns the notion of “illiteracy” on its head by describing the hybrid, transcultural language and literacy practices of Hip Hop youth.

Ayers, W. & Alexander-Tanner, R. (2010). To teach: The journey, in comics. (Chapter 1: Opening day: The journey begins, 1-12). New York: Teachers College Press. This seminal teacher-education text turned comic book dispels teaching myths and discusses what it means to be a “teacher,” practically and ideologically.

Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice, (31), 2, 132-141. Moll and his coauthors describe their collaborative project involving joint research with teachers, students, and families in southern Arizona. He uses his concept of “funds of knowledge” to refer to knowledge about their worlds that children bring to school, and offers ways that teachers can build on such knowledge.

Student Literacy Autobiography: Anonymous (2006). Reading and intellect: Stratification within the classroom.

First Fieldnote due Friday, 9/7 by 11:59 PM

Part 2: Theorizing Learning, Language, and Literacy

WEEK 4 (9/11 and 9/13): Critical Pedagogy and Critical Literacy Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. 30th Anniversary Edition (2000) with an introduction by Donaldo Macedo (71-86). New York: Continuum. In this now classic text by the Brazilian educator, Freire, we are asked to contrast education as ‘banking” with “education as the practice of freedom.”

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In R. Brown (Ed.), Knowledge, Education and Social Change (pp. 56-68). London: Tavistock. EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.7

Bourdieu explains the troubling role of educational institutions in perpetuating social inequalities.

Rodriguez, R. (1981). The achievement of desire. In Hunger of memory: The education of Richard Rodriguez, An autobiography. (pp. 43-73). Boston: D.R. Godine. In this chapter, Rodriguez describes his education, and his resulting feeling of alienation from his family.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2005). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34 (3), 150-65. The author argues for the salience and importance of a “culturally relevant pedagogy,” based on her research with excellent teachers of African American students.

Student Literacy Autobiography: Bang, Katie. (2006). The end of education.

Week 5 (9/18 and 9/20): Learning as Social, Teaching as Scaffolding

Vygotsky, L. (1978) Interaction between learning and development & The prehistory of written language. In M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in society (79-91). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. This is a foundational text that offers a view of learning as social, and represents learning as ushering in development; Vygotsky is also important for this course in privileging "psychological tools"—such as language, writing, and other media—as mediating thinking.

Pratt, M.L. (1999). Arts of the contact zone. In D. Bartholomae & A. Petrosky (Eds.), Ways of Reading, 5th edition. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's Press. Pratt introduces us the term “contact zone”, which she explains as “social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power.” She illustrates the term “autoethnography,” a tactic by which people who have been relegated to marginalized positions of powerlessness seek to regain their agentive voice. Like Vygotsky, she writes about “zones,” but in a quite different sense.

Palinscar, A.S. (2003). Collaborative approaches to comprehension instruction. In Anne P. Sweet & Chatherine E. Snow (Eds.), Rethinking reading comprehension (pp. 99-114). New York: Guilford Press. This chapter describes three teaching techniques for helping students to improve their understanding of what they read that build on Vygotsky’s ideas.

Week 6 (9/25 and 9/27): Language Diversity and Hybridity

Bakhtin, M. (1994). Excerpts from The Bakhtin Reader, Pam Morris (Ed.). London: Arnold (pp. 73-80). This complex theoretical piece introduces the concept of heteroglossia: language and literacy as multiple voices.

Gee, J. P. (1991). “What is Literacy?” In C. Mitchell & K. Weiler (Eds.), Rewriting literacy: Culture and the discourse of the other (pp. 3-11). New York: Bergin & Garvey. A short but valuable piece that adds the term “Discourses” to our literacy vocabulary

Anzaldúa, G. (1987). How to tame a wild tongue. In Borderlands/La Frontera: The new mestiza (pp. 53- 64). San Francisco: Spinsters/Aunt Lute.

EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.8

This essay describes Anzaldúa's experience as a bilingual/biliterate/bicultural woman living along the Texas/Mexico border, attempting to negotiate a number of boundaries that separate languages, peoples, and ideas.

Hudley, A.H.C., & Mallinson, C. (2011). What is Standard English? Understanding English Language Variation in U.S. Schools (pp. 11-36). Teachers College Press. New York, New York. The authors discuss the making, maintenance, and rigidity of Standardized English; and in so doing, they work to elucidate and later deconstruct the ethnocentric ideology that has, up to this point, guaranteed its prominence in our educational system.

Student Literacy Autobiography: Nakagawa, J. (2006). Then what are you doing in America?

Week 7 (10/2 and 10/4): Globalization and Media

Silverstone, R. (2007). Chapter 1: Media and morality. In Media and morality: On the rise of the mediapolis (1-24). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. Silverstone’s book asks us to become “hospitable” readers and writers in our global age, which is intensively mediated by new media technologies, and to imagine uses of media that are ethically and politically alert.

Stornaiuolo, A., Hull, G., & Sahni, U. (2011). Cosmopolitan imaginings of self and other: Youth and social networking in a global world. In J. Fisherkeller (Ed.), International perspectives on youth media: Cultures of production and education: Peter Lang Publishers (pp. 263-280). This book chapter introduces a project that linked youth around the world via social media and asks how such a context can be used, through multimodal literacies, so that we can foster cosmopolitan identities that are ethically alert.

Video: FRONTLINE / WORLD . India - Hole in the Wall . Index page | PBS www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/india/

Selwyn, N. (2013). Chapter 7: “One laptop per child”—A critical analysis. In Education in a digital world: Global perpectives on technology and education (pp. 27-46). New York: Routledge.

Gaudelli, W. (2003). How can you fit a global village in a classroom? Chapter 3 of World class: Teaching and learning in global times (pp. 41-64). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. This excerpt provides a look at several schools that are attempting to incorporate global education within their social studies curriculum.

Part 3: Literacy and Language Policies, Practices, and Debates

Week 8 (10/9 and 10/11): English as a Second Language

Gandara, P., & Orfield, G. (July, 2010). A return to the “Mexican Room”: The segregation of Arizona’s English Learners. The Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles. http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/language-minority-students/a-return-to-the- mexican-room-the-segregation-of-arizonas-english-learners-1 Accessed 8/21/2012. This report reviews research on how linguistic isolation negatively impacts Latino and English learners. It offers a worrisome look at the battle over how to educate language minority students that is being waged across the US but that has achieved national prominence of late in Arizona. EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.9

Wong Fillmore, L. (2009). English language development: Acquiring the language needed for literacy and learning. Research into Practice. Pearson Education. The author explores what is distinctive about the language skills need for literacy in schools and what teachers can do to help English Language learners acquire those skills.

Orellana, M.; Reynolds, J.; Dorner, L.; & Meza, M. (2003). In other words: Translating or “para- phrasing” as a family literacy practice in immigrant households. Reading Research Quarterly, 38(1), 12- 34. This article illustrates the many ways in which multi-lingual children develop and utilize linguistic funds of knowledge at home and how teachers can connect those skills with classroom learning.

Tan, A. (1999). Mother tongue. In S. Gillespie & R. Singleon (Eds.), Across cultures: A reader for writers (pp. 26-31). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. Tan describes the many languages spoken by her mother, an immigrant from China, and reflects on the ways in which her mother's linguistic experiences shaped Tan's own development as a writer.

Student Case Study: LaBerge, Amanda. (2010). The politics of language: A look at how we construct English-learner classrooms and potentiality of bilingual spaces.

Week 9 (10/16 and 10/18): Race, Stereotypes, and Literacy

Gates, Jr., H.L. (1986). 'Race' as the trope of the world. In "Race," writing, and difference (pp. 590-597). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Gates challenges the careless use of "race" as the ultimate trope for irreducible difference between cultures; gives an account of Phyllis Wheatley's "oral examination" to prove that she, as an African girl, was capable of having written a set of poems; rehearses and refutes the European assumption, existing since the 1600's, that Africans were incapable of creating formal literature.

Douglass, F. (1987). Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass. In H.L. Gates, Jr. (Ed.), The Classic Slave Narratives (pp. 273-281). New York: Penguin. This section of Douglass's autobiography gives an account of his learning to read and write, despite the fact that, from the perspective of Douglass's slave owners, "it was unlawful, as well as unsafe, to teach a slave to read."

Jay Z. (2010). Excerpt from Decoded (pp. 1-20). New York: Spiegal & Grau.

Newkirk, T. (2002). Excerpt from Misreading masculinity: Boys, literacy, and popular culture (pp. xv- xxi, 69-91). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. This book is a study of elementary school boys and their relationship to sports, movies, video games, and other avenues of popular culture. The book views these media not as enemies of literacy, but as resources for literacy. The book argues against the simplistic stereotype of boys who are primed to imitate the violence they see. It shows that, rather than mimic, boys most often transform, recombine, and participate in story lines, and resist, mock, and discern the unreality of icons of popular culture.

Student Literacy Autobiography: Ji, Fei. (2006).White.

EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.10

Movie: Nu-Shu: The hidden language of women in China. (1999). This movie is a documentary of a lost written language, invented by women in China, who wanted to find a way to communicate in secret.

Week 10 (10/23 and 10/25)

Data Analysis and Case Study Workshops

Dyson, A.H., & Genishi, C. (2005). Considering the case: An introduction. In On the case: Approaches to language and literacy research (pp.1-18). New York: Teachers College Press. In this introductory chapter to their book on language and literacy research, the authors explain the nature and value of case study research.

Saldana, J. (2009). An introduction to codes and coding. In The coding manual for qualitative researchers (pp. 1-31). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. This is a how-to chapter explaining “coding” as a method of analyzing qualitative data such as field notes. You will code your own field notes and other qualitative data in order to write your case study, and this chapter will show you how.

Week 11 (10/30 and 11/1): The Literacy Wars

Pearson, D. (2004). Excerpts from The reading wars. Educational Policy, 18 (1), 216-252. This article provides a history of debates about how to teach reading in the US. In the end it argues for an “ecologically balanced” approach that includes both a measure of phonics and whole language approaches.

Delpit, Lisa. (1995). The silenced dialogue: Power and pedagogy in educating other people’s children. In Other people's children: Cultural conflict in the classroom (21-47). New York: The New Press. Delpit questions both why some children of color don't learn to read when taught by means of "progressive" and "child-centered" methods and why teachers and parents of color are often excluded in conversations about what is good for their children.

SmartyAnts: Online Early Reading Program

Student Case Study: Von Gerer, Amelia. (2010). The role of multimodal scaffolding in learning to read at St. Anna’s Elementary School.

Week 12 (11/6 and 11/8): The Internet, Multimodality, and Digital Literacy boyd, d.m. (2008). Why Youth ‘Heart’ Social Network Sites: The Role of Networked Publics in Teenage Social Life. Youth, identity, and digital media. David Buckingham (Ed.). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008. 119–142. doi: 10.1162/dmal.9780262524834.119 This article argues that social network sites are a type of networked public with four properties that are not typically present in face-to-face public life: persistence, searchability, replicability, and invisible audiences. These properties fundamentally alter social dynamics, complicating the ways in which people interact. Boyd explores why youth are drawn to such sites and how they change and are changed by social interactions on social network sites.

Lam, W. S. E. (2000). L2 Literacy and the Design of the Self: A Case Study of a Teenager Writing on the Internet. TESOL Quarterly, 34(3), 457-482. EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.11

In this article, Lam describes the experience of an ESL student who becomes a competent and confident member of an English-using online community. Lam shows how this experience writing online led to a transformation in the student’s perceptions of himself as an English language user both online and off.

Hull, G., Kenney, N., Marple, S, & Forsman-Schneider, A. (2006). Many versions of masculine: Explorations of boys’ identity formation through multimodal composing in an after-school program. The Robert F. Bowne Foundation’s Occasional Papers Series. New York: Robert F. Bowne Foundation. This monograph examines how elementary-aged boys used digital storytelling to realize complex masculinities for themselves, senses of self that defied limited and limiting perspectives on malde childhood and adolescence.

Parker, J.K. (2010). Selections from Teaching tech-savvy kids: Bringing digital media into the classroom, grades 5-12. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. These excerpts show how educators capture the power of digital media, with specific examples from classroom teacher-researchers.

Student Literacy Autobiography: Chou, Justin. (2006). Techno-social literacy.

Week 13 (11/13 and 11/15): Re-imagining Literacy as Semiotic Practice

Stein, P. (2004). Representation, rights, and resources: Multimodal pedagogies in the language and literacy classroom. In Bonny Norton & Kelleen Toohey (Eds.), Critical pedagogies and language learning (pp. 95-115). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. This book chapter is based on research and teaching done in post-apartheid South Africa. The author argues for a pedagogy that honors different modes of representation in addition to print.

Katz, M.L. (2008). “Growth in Motion: Supporting Young Women’s Embodied Identity and Development Through Dance After School.” Afterschool matters (Number 7). Dance classes provide a model for afterschool and in-school education where multiple “embodied modes” of teaching and learning enhance development and where risk-taking is rewarded rather than punished.

Razfar, A., & Yang, E. (2010). Digital, hybrid, and multilingual literacies in early childhood. Language Arts, 88 (2), 114-24. As information technologies transform literacy from print-based media into digital, hybrid, and multilingual forms, learning and instruction must adapt. This paper provides relevant insights and practical guidelines drawing on the latest sociocultural research.

Willis, P. Foreword. In The ethnographic imagination (pp. viii-xx). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Student Case Study: Adricula, N. (2011). Rap to me.

Movie: Shakespeare’s Children. This movie is a documentary of a drama project carried out with kids in a Berkeley school.

Week 14 (11/20): Online Courses and Learning: Implications for Education and Literacy

Note: We will not meet in person on 11/20, but will instead operate the course via an online learning platform. EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012 p.12

Week 15 (11/27 and 11/29): Group Performative Reflections

Monday, 12/10: CASE STUDIES due by 11:59 PM

EDU 140AC Syllabus, Fall Semester, 2012