Cortney Steffens Adams Ch. 8: Adding the Phonological Processor: How the Whole System Works Together

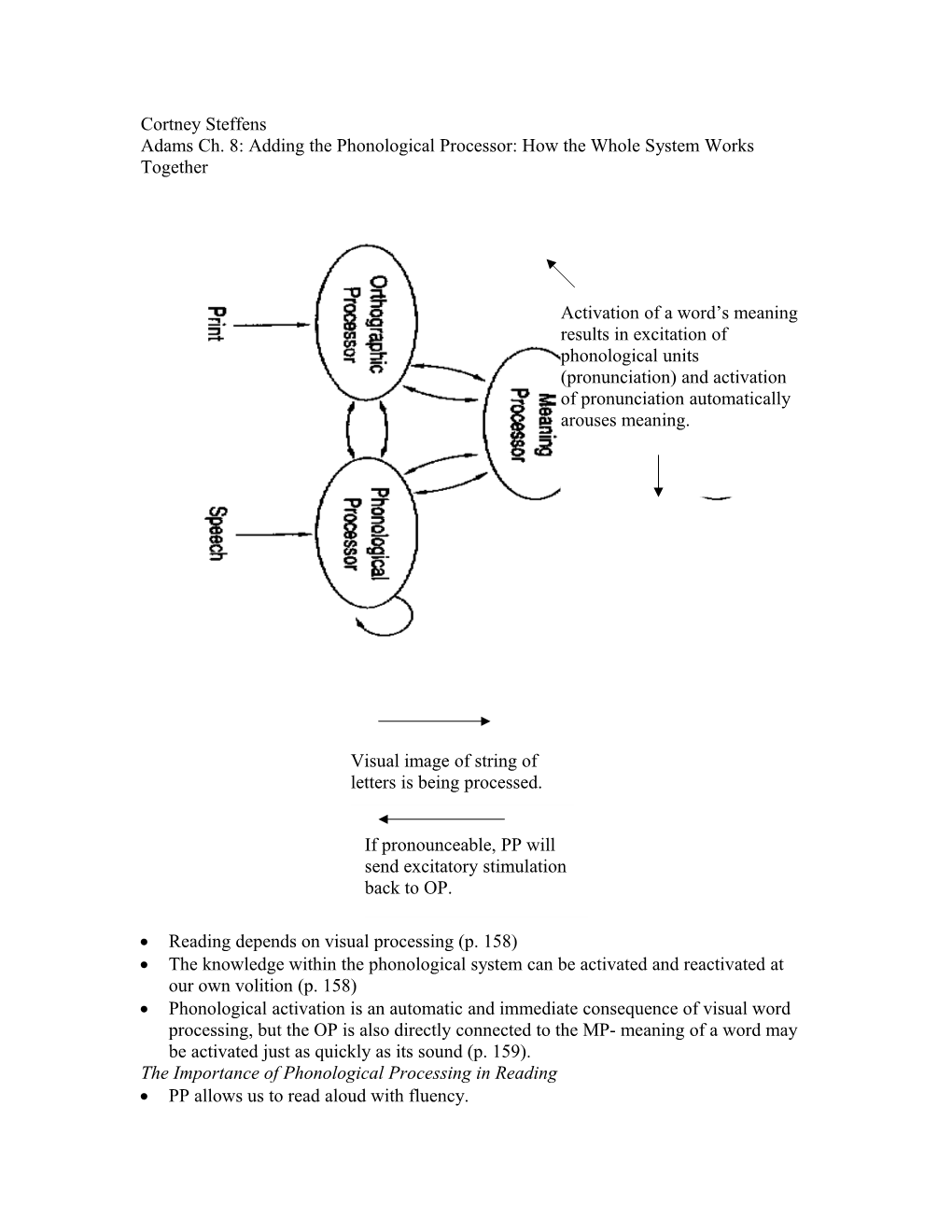

Activation of a word’s meaning results in excitation of phonological units (pronunciation) and activation of pronunciation automatically arouses meaning.

Visual image of string of letters is being processed.

If pronounceable, PP will send excitatory stimulation back to OP.

Reading depends on visual processing (p. 158) The knowledge within the phonological system can be activated and reactivated at our own volition (p. 158) Phonological activation is an automatic and immediate consequence of visual word processing, but the OP is also directly connected to the MP- meaning of a word may be activated just as quickly as its sound (p. 159). The Importance of Phonological Processing in Reading PP allows us to read aloud with fluency. Provides alphabetic back up that maintains speed and accuracy of word recognition Expands on-line memory of individual words essential for text comprehension (p. 159).

Interactions among All Three Processors: The Alphabetic Backup System Accuracy and speed of written word recognition depends on the reader’s familiarity with the word in print (when readers encounter a meaningful word that they have read many times before, the OP will very quickly resonate to the pattern as a whole (p. 160). It is in the reading of less familiar words that the presence of the PP (and the presence and circular connectivity of all three processors) becomes advantageous (p. 161). The coordination of the processors helps to overcome confusions that any of them alone may suffer (p. 162).

Orthographic Processing Vulnerabilities of the OP The OP’s response to a word is dependent on the speed and adequacy with which the individual letters are perceived o Without simultaneous excitation of the letters of a spelling patter the network is debilitated (p. 162). o Difficulties may be due to illegible print or insufficient familiarity with letter identities (p. 163). The OP’s response is also based on the familiarity of the spelling patterns comprising the word. o The more familiar the spelling pattern is, the stronger the associations between its letters. (p. 163).

Compensating for Orthographic Difficulties If identity of the letter and the spelling of the word are well known to the reader, compensation can be achieved within the OP (p. 163).

The CP (Context Processor) reinforces the relevant responses from the MP. Some words may “look” more legible in context (p. 164).

Compensating for the OP’s Lack of Familiarity with the Spelling of a Word The PP helps to recognize visually unfamiliar words- sounding out (p. 164). If familiar response to the word is aroused in the MP or PP, its orthographic image will be reinforced through the feeback they provide (p.165). Any orthographic string that finds a familiar response in one of these processors will find a familiar response in both (p.165). If the other processors anticipate the word (meaningful context or rhyming) their responses will be stronger and more rapid.

Compensating for the Orthographic Processors Inability to Distinguish Real Words from “Well-spelled Frauds” The OP may recognize spelling patterns within nonwords and then must rely on the other processors- this slows responses (p. 166).

Phonological Processing The Dependence of the Phonological Processor on the Speed and Quality of the Orthographic Input If spelling patterns are not orthographically bonded the PP must get the pattern in pieces (p. 168). Any single letter may map onto a number of phonetic translations (c may signal /s/ or /k/ or /ch/ in bocci or /sh/ in suspicion and chute) (p. 168). Visual letter failures result in weak responses.

The Phonological Processor’s Difficulties with Multiple Spelling-Sound Translations The greater the number of phonological responses associated with any given orthographic input, the more phonological responses are possible (ear- bear or dear) (p. 169) and the slower processing occurs.

The Phonological Processor’s Dependence on Familiarity with a Spelling Pattern Speed and strength of a response is a direct product of the frequency with which it has been coupled with the spelling pattern in the past (p. 169). It is not the general frequency with which a word occurs in print but the frequency with which it has occurred in the experience of the person reading it (p. 170).

Compensating for Phonological Difficulties

Compensating for the Phonological Processor’s Problems with Slow Orthographic Processing In contrast to the OP, the workings of the PP are not necessarily defeated by slow letter recognition. Readers can vocally, subvocally, or mentally repeat phonological fragments (t-t-rr-t- rrr—ap) (p. 171). If aurally familiar, the phonological translation will activated a response in the MP (p. 171).

Compensating for the Phonological Processor’s Difficulties with Multiple Spelling-to- Sound Correspondences Ambiguous spelling to sound words tend to be infrequent. If the PP does not immediately respond holistically and thus, uniquely, to an irregularly spelled word on its own, activation of the correct pronunciation from the MP should quickly ensure that it will (p. 171).

Compensating for the Phonological Processor’s Difficulties with Weak Spelling-to- Sound Familiarity The MP receives activation from the CP, OP, and PP- this speeds and strengthens the MP’s response to the OP and PP so that difficulties may be overcome (p. 172).

Compensating for the Phonological Processor’s Indifference to Homographs and Homophones Homographs- spelled identically but mean something different (lead) o Pronunciations are sent to MP o If in isolation, speed and strength of the MP response depends on relative frequencies of the candidate’s meanings Homophones- words that are pronounced identically but mean something different o Orthographic differences compensate for phonological similarities (p. 173).

Processing Meaning Receives input from every other processor and is influenced by speed and accuracy of all the other processors (p. 174). Multiple inputs add to reliability (p. 174). If no coherent response can be produced, without the meaning, no new information nor reciprocal feedback can be issued to any of the other processors (p. 175).

The Meaning Processor’s Dependence on Context The reader’s understanding of the context in which a word occurs can help emphasize the activation of contextually relevant components of the word’s meaning, to select among alternative interpretations of ambiguous words, or create a meaning for the word (p. 175). Determinants of speed and strength of assistance by the CP o Definitiveness and appropriateness of the CP’s expectations (p. 176). o Conscious attention the reader devotes to it- conscious attention is sometimes limited (p. 177).

The Meaning Processor’s Dependence on the Quality and Completeness of the Orthographic and/or Phonological Input For skilled readers the letters of a whole, familiar word are orthographically bonded together and the MP is tapped instantaneously and nearly as quickly it receives excitation from the PP With little orthographic and phonological resolution and little contextual facilitation the reader may fail to recognize a word (p. 177). The Meaning Processor’s Difficulties When the Connections between a Word and its Meaning are Weak The strength in which a meaning is evoked by a particular orthographic and phonological pattern depends on the frequency in which it has been coupled to that pattern in the reader or listener’s experience. (does- to act or female deer?) (p. 179). We swim in the see (p. 180).

Remediating the Meaning Processor’s Weaknesses Supporting Appropriate Use of Context- Younger and less experienced readers tend to rely more heavily on context than more skillful readers. Deliberately bringing jokes, puns, and double entendres into the classroom could help understand multiple meanings (p. 182).

Developing Appropriate Deference to Orthographic Information Repeated readings and spelling-sound instruction enhance orthographic knowledge which enables meaning to occur with less effort.

Reinforcing the Links between Words and their Meanings Excitation from the OP and PP provide back up to enhance meaning (p. 183). If we want children to learn the meanings of new words, they should have opportunities to read and use those words repeatedly- repeated exposure to a word in different contexts (p. 184).

The less frequent a word is, the greater is the amount meaning that it is expected to contribute to a passage; the less frequent a word is, the more strongly the meaning of a passage is expected to depend on its full and proper interpretation (p. 185).

Supporting the Reader’s Running Memory for Text PP’s existence is a consequence of the alphabetic foundation of our script and the opportunity to learn to read by sounding out words (p. 185). Text comprehension is a two-stage process o The reader identifies each successive word and its appropriate meaning as defined by its immediate context (p. 186). o The reader interprets the entire string of words just read, considering the relationships among the just-read words to each other as well as to any relevant background knowledge and larger understanding of the text (p. 186). . Undertaken at syntactic boundaries- between sentences or whole clauses. . Needs proper input- complete and ordered memory of the just read words (p. 187). Skilled readers can neither remember nor comprehend a complex sentence when they are prevented from subvocalizing its wording- Our ability to extend phonological memory through verbal rehearsal (p. 188). Less skillful readers have slower decoding, must invest considerable effort in all aspects of reading, and less inclined to use verbal rehearsal (p. 189).