The Haitian Cultural Recovery Project an Interview with Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Consideration of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention Richard Kurin

Document generated on 09/25/2021 5:44 a.m. Ethnologies U.S. Consideration of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention Richard Kurin Patrimoine culturel immatériel Article abstract Intangible Cultural Heritage UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Volume 36, Number 1-2, 2014 voted overwhelmingly at the biennial meeting of its General Conference in Paris on October 17, 2003 to adopt a new international Convention for the URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1037612ar Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. That Convention became DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1037612ar international law on April 30, 2006. By the end of 2006 it had been ratified or accepted by 68 countries; today, that number is approaching universal acceptance with more than 160 nations having acceded to the convention. At See table of contents the 2003 session, some 120 nation-members voted for the convention; more registered their support subsequently. No one voted against it; only a handful of nations abstained – Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United Publisher(s) States among them. Within some of those nations, debate over whether to ratify the treaty continues. In this paper, the author considers the convention Association Canadienne d’Ethnologie et de Folklore and unofficially examines the U.S. government position with regard to why support for it was withheld in 2003, how deliberations have proceeded since ISSN then, and whether or not the U.S. might ultimately accept the treaty. 1481-5974 (print) 1708-0401 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Kurin, R. (2014). U.S. Consideration of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Convention. -

“Northern Ireland at the Smithsonian”

“NORTHERN IRELAND AT THE SMITHSONIAN” REPORT ON PARTICIPATION IN THE 41ST SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL, 2007 Report by Pat Wilson NI Project Manager Smithsonian Unit June 2008 1 CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 - 36 MAIN REPORT 37 -111 1. INTRODUCTION 38 The Smithsonian Folklife Festival 38 The Rediscover Northern Ireland Programme 38 2. BACKGROUND 40 Memorandum of Understanding 40 Financial Memorandum 41 Budget 42 3. DELIVERY STRUCTURES 45 Steering Groups 45 Leadership Group including VIPs 45 Coordinating Group 45 Curatorial Group 46 Administrative / Coordinating Team 46 4. LOGISTICS 50 Transportation and Freight 50 Flights 52 A c c ommodation 53 Insurance 54 5. COMMERCIAL ACTIVITIES 55 Marketplace 55 Food Concession 57 Folkways Recording 60 2 Sponsorship 61 6. COMMUNICATIONS 65 Marketing & Public Relations 65 Website 66 Media Handling 68 7. FESTIVAL 69 Political Support 69 Programming Logistics 70 Research 70 Themes for programme content 71 8 December 2006: reveal of outline programme 72 Administration 72 Issue of invitations, recording of acceptance and 73 associated consequentials Special events prior to attending the Festival 74 Receptions & Events in Washington DC 77 Opening Ceremony 79 8. POST FESTIVAL ACTIVITIES 82 Surveys and evaluation 82 Participants and sponsors’ feedback 82 Smithsonian Survey 82 DCAL survey of participants and sponsors 83 Conclusion of administration matters including 83 payments Capture and collation of research materials, 84 recordings and filmed materials 9. MONITORING AND MEASURING PERFORMANCE 84 3 10. CHALLENGES / LESSONS LEARNED 97/102 11. LEGACY OPPORTUNITIES 103 12. CONCLUSION 110 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank our colleagues in the Smithsonian Institution, Richard Kurin, Diana Parker, Barbara Strickland and especially Nancy Groce who made it possible for Northern Ireland to demonstrate its cultural traditions on the National Mall at the annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival in 2007. -

Smithsonian Institution (SI) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes, 2013-2017

Description of document: Smithsonian Institution (SI) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Board of Trustees Meeting Minutes, 2013-2017 Requested date: 18-June-2017 Released date: 03-October-2018 Posted date: 15-October-2018 Source of document: Records Request Assistant General Counsel Smithsonian Institution Office of General Counsel MRC 012 PO Box 37012 Washington, DC 20013-7012 Fax: 202-357-4310 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 0 Smithsonian Institution Office of General Counsel VIA US MAIL October 3, 2018 RE: Your Request for Smithsonian Records (request number 48730) This responds to your request, dated June 18, 2017 and received in this Office on June 27, 2017, for "a copy of the meeting minutes from the Hirschhorn (sic) Museum Board of Trustees, during the time period 2013 to present." The Smithsonian responds to requests for records in accordance with Smithsonian Directive 807 - Requests for Smithsonian Institution Information (SD 807) and applies a presumption of disclosure when processing such requests. -

Inclusive Museum

VOLUME 5 ISSUE 2 The International Journal of the Inclusive Museum __________________________________________________________________________ Melting Pot on the Mall? Race, Identity, and the National Museum Complex NICOLE REINER INCLUSIVEMUSEUM.COM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE INCLUSIVE MUSEUM http://onmuseums.com/ First published in 2013 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Publishing University of Illinois Research Park 2001 South First St, Suite 202 Champaign, IL 61820 USA www.CommonGroundPublishing.com ISSN: 1835-2014 © 2013 (individual papers), the author(s) © 2013 (selection and editorial matter) Common Ground All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please contact <[email protected]>. The International Journal of the Inclusive Museum is a peer-reviewed scholarly journal. Typeset in CGScholar. http://www.commongroundpublishing.com/software/ Melting Pot on the Mall?: Race, Identity, and the National Museum Complex Nicole Reiner Abstract: This essay reports on the controversial proposal to establish a National Museum of the American People (NMAP) on the Mall in Washington, D.C., and situates it in terms of the emergence of ethnically-specific museums at the Smithsonian during the past two decades, in- cluding the National Museum of African American -

The Festival: Making Culture Public

The Festival: Making Culture Public by Richard Kurin makers, writers, tour operators, and many others. In a public institution like the Smithsonian, an he past few years have seen an increasing alysis needs to be coupled with action. Exhibitions, concern with issues of public cultural repre programs, and displays often reflect cultural poli Tsentation. A host of symposia and books cies and broad public sentiments, but they may also examine how culture and history have been pub serve as vehicles for legitimating outdated senti licly presented in museums, at Olympics, through ments and policies as well as encouraging alterna the Columbus Quincentenary, presidential inaugu tive ones. Programs can address public knowledge, rals, festivals, and other mega-events. Controversy discourse, and debate with considerable care, ex now swirls around Disney's America and issues of pertise, and ethical responsibility. But scholars and authenticity and accuracy in the presentation of curators have good cause to worry that their efforts American history to mass audiences. will be eclipsed by those with greater access to larg More than when the Smithsonian was founded in er audiences. 1846 for "the increase and diffusion of knowledge," How then to understand the Smithsonian's communicating cultural subjects to broad publics is Festival of American Folklife in this context? What big, and serious, business. New genres of represen is it? How does it display and represent culture? tation are emerging, such as "infotainment," history And what does it suggest about the role of muse and culture theme parks, various forms of multime ums and cultural institutions with regard to the dia, and equivalents of local access cable TV across people represented? the globe. -

Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: Key Factors in Implementing the 2003 Convention

Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: Key Factors in Implementing the 2003 Convention Richard Kurin Implementing the 2003 Convention Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: Key Factors in Implementing the 2003 Convention* Richard Kurin Director, Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, USA Introduction transmission of intangible cultural heritage by working In 2003, at the biennial General Conference of UNESCO closely and cooperatively with the relevant communities. its Member States voted overwhelmingly for the adoption Importantly, the Convention recognises as ICH only of a new international treaty : the Convention for the those forms of cultural expression consistent with human Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. The rights. At the international level, a new International Convention aims to ensure the survival and vitality of the Committee elected from the States Parties to the new world’s living local, national, and regional cultural Convention will develop two lists - one of representative heritage in the face of increasing globalisation and its traditions proposed by member states, and the other of perceived homogenising effects on culture (Matsuura endangered traditions in urgent need of safeguarding and 2004). Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) - a loose English eligible for financial support from a newly established translation of the Japanese mukei bunkazi, is broadly international fund. The text of the treaty has been widely defined in terms of oral traditions, expressive culture, the distributed and is available on the UNESCO website (1). social practices, ephemeral aesthetic manifestations, and The Convention came into effect in April 2006. By the end forms of knowledge carried and transmitted within of May 2007 seventy-eight nations had ratified it - among cultural communities. -

Q2 FY 2012 EDITED.Indd

Scores of people, including President Barack Obama, gathered on the National Mallon February 22, 2012, to celebrate the historic groundbreaking for the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Pictured, from left to right, are Museum Council Cochair Richard D. Parsons, Board Vice Chair Patricia Q. Stonesifer, former First Lady Laura Bush, Smithsonian Secretary G. Wayne Clough, Museum Director Lonnie Bunch; Under Secretary for History, Art, and Culture Richard Kurin, Board Chair France Córdova, and Museum Council Cochair Linda Johnson Rice. Report to the Regents Second Quarter, Fiscal Year 2012 Broadening Access: Visitation Summary Th rough the second quarter of fi scal year 2012, the Smithsonian counted approximately 10.6 million visits to its museums and exhibition venues in Washington, D.C., and New York, plus the National Zoological Park and Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Th is was similar to the fi gure for the fi rst two quarters of fi scal year 2011. Th e Smithsonian also counted about 40 million unique visitors to its websites and approximately 2 million visitors to traveling exhibitions mounted by the Smithsonian Th e Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service’s Jim Henson’s Fantastic World at the Museum Institution Traveling Exhibition Service. of the Moving Image Visits to Smithsonian Venues First Two Quarters, Fiscal Years 2010, 2011, and 2012 3,000,000 2,500,000 2,000,000 1,500,000 FY 2010 FY 2011 1,000,000 FY 2012 500,000 0 Postal SI Castle SI Renwick Anacostia Hirshhorn African Art African Udvar-Hazy National Zoo Ripley Center Ripley Air and Space Freer/Sackler Natural History Heye Center-NY American Indian Reynolds Center Reynolds American History American Cooper-Hewitt-NY Report to the Regents, June 2012 1 Grand Challenges Highlights Understanding and Sustaining a Biodiverse Planet Research: Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) In this quarter, SERC researchers published 26 papers in 20 peer- reviewed journals. -

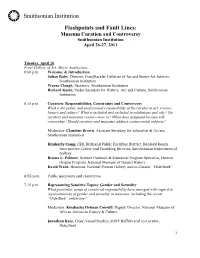

Flashpoints and Fault Lines: Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian Institution Flashpoints and Fault Lines: Museum Curation and Controversy Smithsonian Institution April 26-27, 2011 Tuesday, April 26 Freer Gallery of Art, Meyer Auditorium 6:00 p.m. Welcome & Introduction Julian Raby, Director, Freer|Sackler Galleries of Art and Senior Art Advisor, Smithsonian Institution Wayne Clough, Secretary, Smithsonian Institution Richard Kurin, Under Secretary for History, Art, and Culture, Smithsonian Institution 6:15 p.m. Curation: Responsibilities, Constraints and Controversy What is the public and professional responsibility of the curator in art, science, history and culture? What is included and excluded in exhibitions and why? Do curators and museums censor—how so? When does judgment become self- censorship? Should curators and museums address controversial subjects? Moderator: Claudine Brown, Assistant Secretary for Education & Access, Smithsonian Institution Kimberly Camp, CEO, Richland Public Facilities District, Hanford Reach Interpretive Center and Founding Director, Smithsonian Experimental Gallery Briana L. Pobiner, Science Outreach & Education Program Specialist, Human Origins Program, National Museum of Natural History David Ward, Historian, National Portrait Gallery and co-Curator, “Hide/Seek” 6:55 p.m. Public questions and comments 7:15 p.m. Representing Sensitive Topics: Gender and Sexuality What particular issues of curatorial responsibility have emerged with regard to representations of gender and sexuality in museums, including the recent “Hide/Seek” exhibition? Moderator: Kinshasha Holman Conwill, Deputy Director, National Museum of African American History & Culture Jonathan Katz, Chair, Visual Studies, SUNY Buffalo and co-Curator, Hide/Seek 1 Charles Francis, Founder, Kameny Papers Project Thom Collins, Director, Miami Art Museum Karen Milbourne, Curator, National Museum of African Art 8:05 p.m. -

Smithsonian Institution (SI) Meeting Minutes from the National Museum of American History Board, 2012-2017

Description of document: Smithsonian Institution (SI) meeting minutes from the National Museum of American History Board, 2012-2017 Requested date: 13-June-2017 Release date: 19-February-2019 Posted date: 29-July-2019 Source of document: Records Request Assistant General Counsel Smithsonian Institution Office of General Counsel MRC 012 PO Box 37012 Washington, DC 20013-7012 Fax: 202-357-4310 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site, and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 0 Smithsonian Institution -

Dr. Richard Kurin

FREER|SACKLER BIO Dr. Richard Kurin Acting Director of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the Freer Gallery of Art As a member of the Smithsonian’s senior leadership team, Kurin helps guide the Institution’s national museums, preeminent research centers, and educational programs with a staff of 6,500 and annual budget of $1.5 billion. His areas of focus are the Smithsonian’s strategic direction, institutional partnerships, public representation, philanthropic support, and special initiatives. In early 2018, he took on the additional duties of serving as acting director of the Freer|Sackler following the retirement of longtime director Julian Raby. An anthropologist with a PhD from the University of Chicago, Kurin specialized in the study of South Asia and Muslim societies. He has held Fulbright and Social Science Research Council Fellowships, taught at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, and authored six books and scores of scholarly articles. He coordinated the Smithsonian’s Festival of India programs in the 1980s, has collaborated closely with Yo-Yo Ma and the Silkroad Ensemble since the late 1990s, and has continued to work on a variety of projects throughout Asia over a forty-year career. Prior to his current roles, Kurin served as the Smithsonian’s acting provost and under secretary for museums and research from 2015, and from 2007 he served as under secretary for history, art, and culture. He was responsible for oversight of all of the Smithsonian’s museums, scientific research, and cultural centers. For two decades before that, Kurin directed the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, overseeing the annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall and Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. -

Director's Administrative Records, 1967-2013

Director's Administrative Records, 1967-2013 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Director's Administrative Records http://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_arc_379413 Collection Overview Repository: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C., [email protected] Title: Director's Administrative Records Identifier: Accession 15-341 Date: 1967-2013 Extent: 23 cu. ft. (23 record storage boxes) Creator:: Smithsonian Institution. Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage Language: Language of Materials: English Administrative Information Prefered Citation Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 15-341, Smithsonian Institution. Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, Director's Administrative Records Use Restriction Restricted for 15 years; until Jan-01-2029. Boxes 1-3, 6-7, 11, and 20-22 contain -

Folklife in Contemporary Multicultural Society

FoLKLIFE IN CoNTEMPORARY MuLTICULTURAL SociETY Richard Kurin ew demographic, political, economic and long term sustainable development (Cultural Survival ecological realities have recently joined on Quarterly 1982 6(2), 1984 8(3), 1987 11(1)). The ongo a global scale to bring cultural issues to the ing, systematic destruction of the tropical rainforest for N fore. Talk about "culture" - usually con industrial and agricultural purposes contrasts sharply signed to the back sections of newspapers, to academic with its use by its original human inhabitants. Indige circles and to abstract critical discussions- has recently nous people of the rainforests generally have developed emerged as a major subject of current events requiring systems of knowledge and resource use that conserve serious and broad consideration. both nature and culture. Traditional, local relationships In the United States the 1990 Census will reveal the with an environment, be it rainforest, wetland, moun continuation of a trend toward an ethnically diverse tainous region, sea coast or other area, are most often population. Sometime in the middle of the next century more ecologically sound than those of advanced indus most Americans will be identified as of African Ameri trial society. can, Asian American, Hispanic or other "minority" back These events and trends are both sobering and ground. The "majority," already a broad and varied humbling. They remind us that grass-roots, people's category of European Americans, will have become the culture - folklife - a residual category for many "minority." The implications of this demographic shift, decades if not the entire century, is an important force already well along in some areas of the United States, in the world today, directly affecting demographic, po has sparked debate on the public use of languages other litical, economic and ecological change.