POL 205 Asian Politics Dr. Lairson Singapore

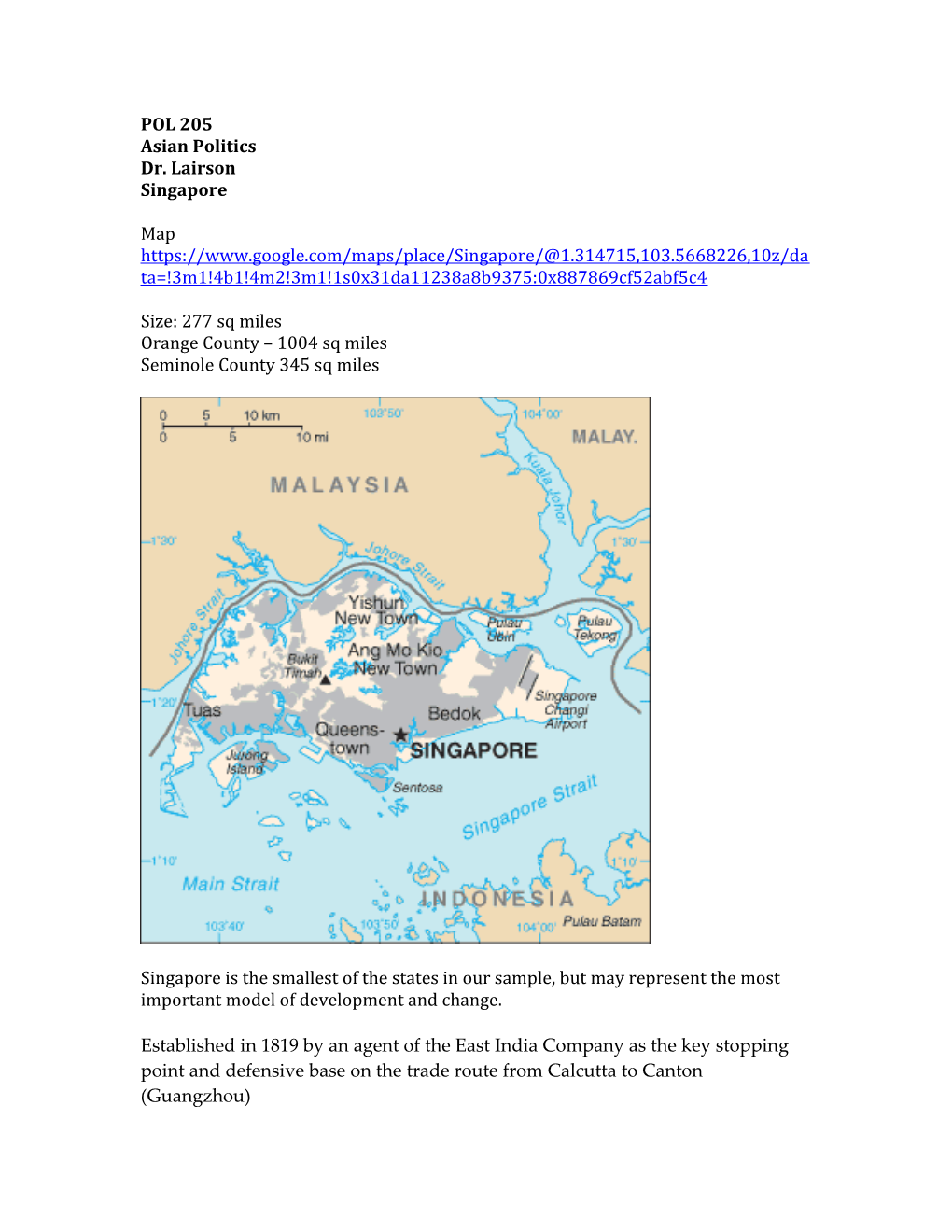

Map https://www.google.com/maps/place/Singapore/@1.314715,103.5668226,10z/da ta=!3m1!4b1!4m2!3m1!1s0x31da11238a8b9375:0x887869cf52abf5c4

Size: 277 sq miles Orange County – 1004 sq miles Seminole County 345 sq miles

Singapore is the smallest of the states in our sample, but may represent the most important model of development and change.

Established in 1819 by an agent of the East India Company as the key stopping point and defensive base on the trade route from Calcutta to Canton (Guangzhou) Agricultural production in the mid 19th century drew many Chinese laborers to Singapore, most of them from southeast China.

By 1860, considerable commercialization in Singapore.

At the same time, the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 led to an increase in trade operating through Singapore.

Later in the 19th century, technological changes in the demand for rubber led to commercial rubber farms in Malaya with these products shipped out through Singapore.

Tin mining enterprises, also in Malaya, developed at about the same time. The growth of rubber and mining of tin led to an influx of Indian labor into British- controlled Malaya.

Between the 1880s and 1930, a sophisticated system of trading, financial institutions and logistics arose in Singapore linking capitalist production and global distribution. Singapore’s exports rose more than ten-fold from 1883 to 1926.

1900 Singapore Chinese entrepreneurs in the years between 1900-1940 established firms for milling rubber, manufacturing capital equipment for rubber production, and for the production of rubber products (such as shoes) for sale internationally. These businesses were also essential for creation of a significant Chinese banking sector.

British management of Singapore was very light and provided very little in public goods. Chinese community organizations were as important as the Colonial government. Growing size of British-education Chinese elite.

Management, finance and organization were among the highest knowledge intensive operations for this era. Within Asia, Singapore was able to develop among the most sophisticated capabilities in these areas, with both Europeans and Chinese involved.

But this was a thin veneer on top of a very impoverished labor force.

The global depression of the 1930s followed by World War II devastated the Singapore economy and much of its infrastructure.

Revolutionary nationalism in China was transplanted to Singapore in labor organization and labor unions. Rickshaw pullers efforts to increase wages were an important example. In Malaysia, a significant Communist Party emerged among Chinese workers.

World War II destroyed the British capacity to retain control over Singapore and Malaya, in large part by removing the British from physical control and through the political mobilization of much of Singapore society.

Postwar Singapore found a dramatic increase in political activity, much of it focused on independence. During the mid-1950s, Singapore was an island with high levels of political mobilization operating in an environment of gangs, slums and swamps.

The People’s Action Party (PAP) was founded in the mid 1950s. Led by British- trained economic and intellectual elites with a strong non-Communist but Leninist streak, the PAP moved ruthlessly in this environment to gain and retain political power in order to transform Singapore. One of the key leaders from the beginning was Lee Kuan Yew. Attempting to manage the volatile situation were the British, who called for elections in 1955 to establish a local government with limited powers. The PAP participated in that election with some success, articulating very radical positions on immediate independence and a socialist economy.

The moderates, led by Lee Kuan Yew, in the next two years worked to incorporate the political tactics of the Communist elements in PAP. And in the elections of 1959 the PAP won a decisive victory. Full internal self government in 1959 was followed by independence in 1963.

PAP quickly replaced the independent labor organization with a state-controlled labor organization.

In the early 1960s, Lee moved toward union with Malaysia as the answer to Singapore’s problems. Many radical elements in PAP resisted and the government had them arrested.

The union with Malaysia took place in 1963 but was dissolved in 1965. Muslim Malaysia was incompatible with Chinese Singapore and Muslim Indonesia placed trade sanctions on the new nation.

PAP and Singapore faced an existential threat in years after 1965: loss of Malaysian partner, British close naval base, economic growth threatened. PAP fears Chinese capitalists as threat to their power.

Emergence of a strategy of industrial production and manufacturing for the world economy, based on low wages but highly trained workers, good infrastructure, and attracting FDI. Leninist dimensions of the PAP The PAP leaders share a set of beliefs and attitudes that constitute elements of an ideology, but not one that fits traditional categories. The main features of this “ideology” include the assumption of a world based in conflict, a strong commitment to rationality and pragmatism, a belief in the value of elite rule and selection of leaders based entirely on merit, fusion of Party and State bureaucracy, a deep hostility to corruption, and the necessity for depoliticizing policy choices by controlling society and repressing political opposition.

Building state capitalism

Government-Linked corporations (GLCs). These new agencies include the Jurong Town Corporation, which engaged in building the industrial estates infrastructure for foreign firms, the Public Utilities Board provided water, gas and electricity to the industrial estates, and the Development Bank of Singapore focused on providing the investment assistance (including equity investment) to support firms locating in Singapore.

The Singapore Institute for Standards and Industrial Research engaged in defining and defusing quality control standards and the Technical Education Department of the Ministry of Education and the Singapore Management Institute expanded technical and managerial education.

In addition, Singapore created a set of GLCs able to produce local entrepreneurial capabilities tied to the state and its economic strategy. The Port of Singapore Authority was responsible for management, expansion and upgrading of the port and the Neptune Orient Lines focused on providing shipping services for goods traded with Singapore. Along with GLCs in ship repair, oil exploration, petroleum refining, air travel, metal engineering, chemical and electrical equipment and appliances these firms provided market and profit- oriented firms controlled by the state and able to make important contributions to economic capabilities and dynamism in Singapore.

Labor suppression to control wage growth Education to upgrade skills Central Provident Fund to aggregate capital Public housing Economic growth via state capitalism, TNC investment brings technology and access to global markets, and a development regime provided the political basis for growth.

Jurong industrial estate – SEZ for MNCs Public housing in Singapore % GDP Manufac. Manu. Export Savings Invest. Year Growth % GDP % GDP % GDP % GDP 1960 16.6 10.7 -2.4 11.4 1961 8.5 -2.3 11.6 1962 7.1 5.9 15.6 1963 10.5 3.8 17.5 1964 -4.3 9.2 20.0 1965 6.6 11.5 21.9 1966 10.6 12.7 16.3 22.0 1967 13.0 20.5 13.6 16.3 22.2 1968 14.3 20.0 24.9 1969 13.4 17.0 19.4 28.6 1970 13.4 24.8 19.5 38.7 1971 12.5 18.8 40.6 1972 13.3 24.4 41.4 1973 11.3 28.4 27.0 39.4

Source: W.G. Huff, The Economic Growth of Singapore, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, 412-413, 303, 305

The principal industries where manufacturing growth occurred were textiles, transportation equipment, petroleum refineries and especially in electronics and electrical machinery.

Though oil was a major industry for Singapore, the real growth area for employment was certainly in electrical machinery and electronics. This came at first as U.S. and later European and Japanese electronics firms set up labor- intensive and low skill assembly operations in Singapore. This was to take advantage of the complementary assets the government had assembled: political and macroeconomic stability, government administrative efficiency and lack of corruption, high quality infrastructure, monetary incentives, and low wage-high productivity workers. Of particular long term importance was the location of the test and assembly part of the production of semiconductors by firms such as Texas Instruments, National Semiconductor, SGS-Thomson, Hewlett-Packard, and NEC. The Singapore exception Singapore, it is sometimes joked, is “Asia-lite”, at the geographical heart of the continent but without the chaos, the dirt, the undrinkable tap water and the gridlocked traffic. It has also been a “democracy-lite”, with all the forms of democratic competition but shorn of the unruly hubbub—and without the substance. Part of the “Singapore exception” is a system of one-party rule legitimised at the polls and, 56 years after Mr Lee’s People’s Action Party (PAP) took power, facing little immediate threat of losing it. The system has many defenders at home and abroad. Singapore has very little crime and virtually no official corruption. It ranks towards the top on most “human-development” indicators such as life expectancy, infant mortality and income per person. Its leaders hold themselves to high standards. But it is debatable whether the system Mr Lee built can survive in its present form. It faces two separate challenges. One is the lack of checks and balances in the shape of a strong political opposition. Under the influence of the incorruptible Lees and their colleagues, government remains clean, efficient and imaginative; but to ensure it stays that way, substantive democracy may be the best hope. Second, confidence in the PAP, as the most recent election in 2011 showed, has waned somewhat. The party has been damaged by two of its own successes. One is in education, where its much-admired schools, colleges and universities have produced a generation of highly educated, comfortably off global citizens who do not have much tolerance for the PAP’s mother-knows-best style of governance. The PAP’s second success that has turned against it is a big rise in life expectancy, now among the world’s longest. This has swelled the numbers of the elderly, some of whom now feel that the PAP has broken a central promise it had made to them: that in return for being obliged to save a large part of their earnings, they would enjoy a carefree retirement. And it is not just old people who have begun to question PAP policies. Many Singaporeans are uncomfortable with a rapid influx of immigrants. These worries point to Singapore’s two biggest, and linked, problems: a shortage of space and a rapidly ageing population. PAP elections Baby bust and immigration FIFTY YEARS OF breakneck growth have left Singapore’s economy in a position of enviable strength. Since 1976, GDP growth has averaged 6.8% a year. The past decade has seen vertiginous swings, from a slight recession in 2009 as the global crisis battered a very trade-dependent economy to a 15.2% leap in GDP in 2010. Since then growth has stabilised in the range of 2-4% a year, which the government expects to continue for the next few years. Unemployment is low, just under 2%, and prices are subdued without stoking worries about deflation. The national finances look just as robust. Thanks to the CPF, Singapore enjoys a very high saving rate: nearly 50% of GDP. With investment averaging a still impressive 30% or so of GDP a year, the country has a structural surplus on its current account which last year reached 19% of GDP, a higher proportion than in any other developed economy. It also maintains a consistent fiscal surplus in conventional terms. The constitution mandates that the budget must be balanced over the political cycle, but ring-fences half of the projected long-term investment income earned on the government’s reserves. When all the returns were added in, estimated the IMF, the surplus for the fiscal year ending March 2014 was 5.7% of GDP, compared with the official figure of 1.1%. Current Economic Strtegy The strategy has been to spot opportunities and to make investment irresistibly attractive for multinationals. Five priorities for future “growth clusters” were listed in this year’s budget: advanced manufacturing; aerospace and logistics; applied health sciences; “smart urban solutions”; and financial services. Singapore, says Beh Swan Gin, chairman of the Economic Development Board, which promotes inward investment, is now seeking a “much more expansive role” in the business activities of the firms located there—not just as an offshore manufacturing location but as home to many more of their functions. When it comes to domestic business, it is striking, in a country that boasts about keeping the state lean, how many of its most successful companies are “GLCs” (“government-linked”) in which, through Temasek, the government has a substantial stake. They include DBS (the largest domestic bank); NOL (shipping); SingTel (telecoms); SMRT (public transport); ST Engineering (high-end engineering services); CapitaLand (property); Keppel (marine engineering, such as jack-up rigs, in which Singapore has a 70% global market share); and SembCorp (marine engineering and utilities). Besides thriving property developers, Singapore does have innovative and expansive private companies, such as BreadTalk, a baker with a presence in 15 countries; Charles & Keith, an international chain of shoe shops; and Hyflux, which is building an export market using Singapore’s expertise in power- and water- management. But Singapore’s best-known brand remains that of a GLC: Singapore Airlines, its flag- carrier. In finance as in manufacturing, Singapore plays host to the world’s biggest institutions but rarely wins prizes itself. Its three local banks—DBS, UOB and OCBC—are protected in their local market, a bone of contention when Singapore negotiates free-trade agreements and an irritation to foreign visitors, who find it harder to pinpoint a hole in the wall that will accept their debit cards than they do in Ulaanbaatar or Mandalay. In terms of market capitalisation, Singapore’s stock exchange is dwarfed by those in Hong Kong, Shanghai and Tokyo, its main regional rivals as financial centres. Yet the city has overtaken Shanghai and Tokyo to become the largest centre in its time-zone for foreign- exchange trading, and globally lags behind only New York and London. Asked how it has managed this, Marshall Bailey, president of ACI, the Financial Markets Association, points to its being English-speaking and having high standards of governance. It is also, of course, Chinese-speaking, and is the biggest offshore trading centre for the Chinese yuan outside Hong Kong. Besides that, it is a centre for derivatives-trading and for the insurance industry, as well as home to 14,000 commodity traders and a thriving base for asset management and private banking, fast catching up with Switzerland. It is also gaining in importance as a legal centre for international arbitration. Population growth might threaten that, particularly if it leads to traffic gridlock, “the easiest way to strangle Singapore”, according to Kishore Mahbubani, dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School. One of the city’s biggest failures, he argues, has been that its public-transport system has not kept up with population growth, despite the hectic pace of underground-railway construction. Buying a car is very expensive, thanks to the rationing and auctioning of licences (currently an excruciating S$66,000 for a small vehicle). But running costs are quite low, despite an electronic road-pricing system that penalises drivers in the centre of town and at peak hours, so there is a perverse incentive to drive. And car ownership is still part of the “Singaporean dream”.