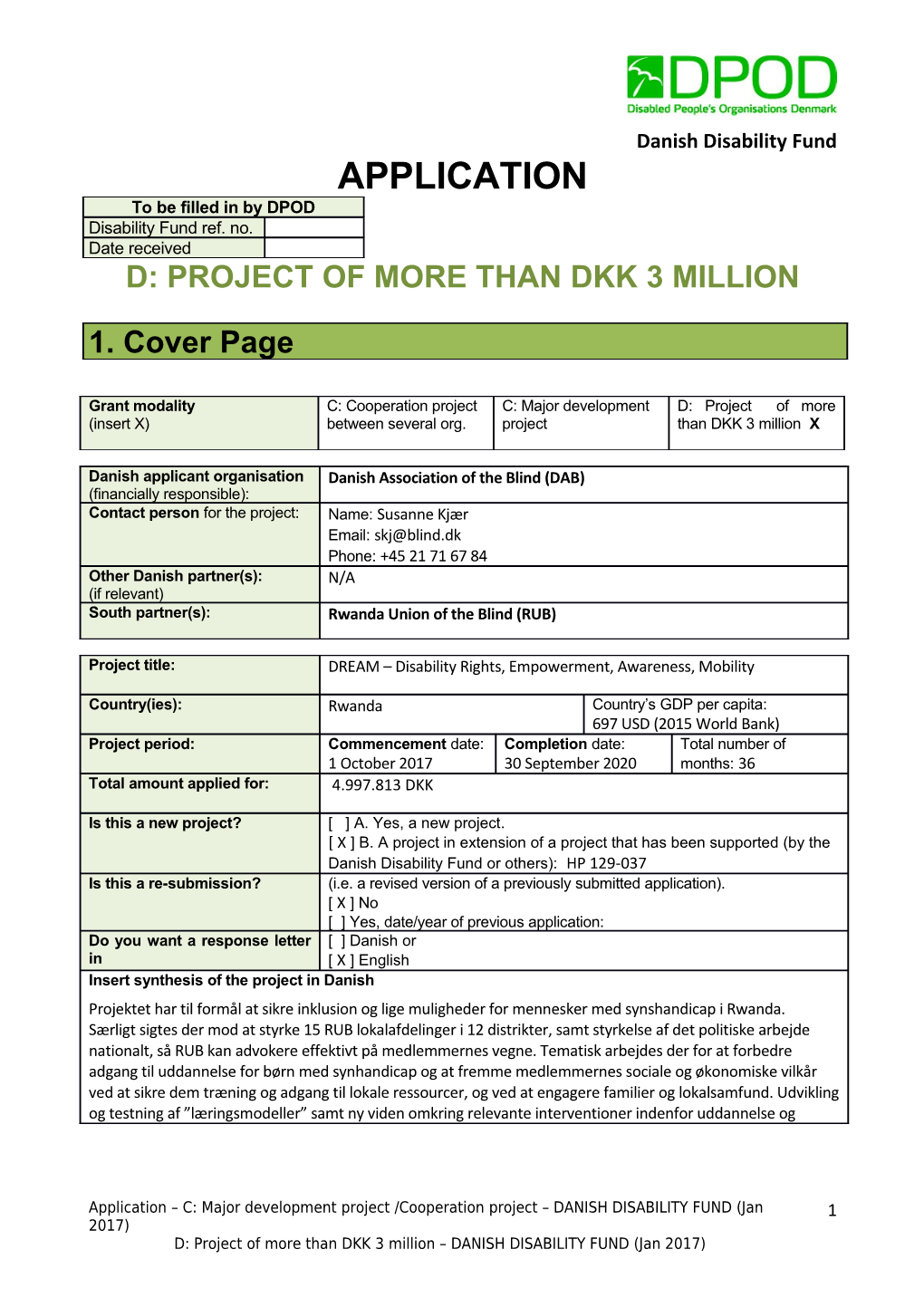

Danish Disability Fund APPLICATION To be filled in by DPOD Disability Fund ref. no. Date received D: PROJECT OF MORE THAN DKK 3 MILLION

1. Cover Page

Grant modality C: Cooperation project C: Major development D: Project of more (insert X) between several org. project than DKK 3 million X

Danish applicant organisation Danish Association of the Blind (DAB) (financially responsible): Contact person for the project: Name: Susanne Kjær Email: [email protected] Phone: +45 21 71 67 84 Other Danish partner(s): N/A (if relevant) South partner(s): Rwanda Union of the Blind (RUB)

Project title: DREAM – Disability Rights, Empowerment, Awareness, Mobility

Country(ies): Rwanda Country’s GDP per capita: 697 USD (2015 World Bank) Project period: Commencement date: Completion date: Total number of 1 October 2017 30 September 2020 months: 36 Total amount applied for: 4.997.813 DKK

Is this a new project? [ ] A. Yes, a new project. [ X ] B. A project in extension of a project that has been supported (by the Danish Disability Fund or others): HP 129-037 Is this a re-submission? (i.e. a revised version of a previously submitted application). [ X ] No [ ] Yes, date/year of previous application: Do you want a response letter [ ] Danish or in [ X ] English Insert synthesis of the project in Danish Projektet har til formål at sikre inklusion og lige muligheder for mennesker med synshandicap i Rwanda. Særligt sigtes der mod at styrke 15 RUB lokalafdelinger i 12 distrikter, samt styrkelse af det politiske arbejde nationalt, så RUB kan advokere effektivt på medlemmernes vegne. Tematisk arbejdes der for at forbedre adgang til uddannelse for børn med synhandicap og at fremme medlemmernes sociale og økonomiske vilkår ved at sikre dem træning og adgang til lokale ressourcer, og ved at engagere familier og lokalsamfund. Udvikling og testning af ”læringsmodeller” samt ny viden omkring relevante interventioner indenfor uddannelse og

Application – C: Major development project /Cooperation project – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 1 2017) D: Project of more than DKK 3 million – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 2017) Danish Disability Fund beskæftigelse vil blive brugt strategisk til at påvirke myndigheder og andre relevante aktører med henblik på implementering af gældende politikker og inklusion i ”mainstream” programmer og services. Et øget samarbejde med bl.a. paraplyorganisationen NUDOR vil blive etableret i den henseende. Fokus på bæredygtighed er desuden gennemgående i projektet via udveksling af erfaringer, ”peer support” og ToT træning, samt intensiv fundraising. 2. Aplication text

1. WHAT IS THE CONTEXT AND THE PROBLEM? (suggested length: C applications 4-5 pages, D applications 4-6 pages)

1.a The overall context 1 Rwanda has made good progress over the last two decades since the enormous challenges it faced in the aftermath of the genocide in 1994 that destroyed the country’s entire social and economic fabric. Rwandans have benefited from rapid economic growth, reduced poverty, more equality and increased access to services, including health and education. Improvements in living standards are evidenced by e.g. the attainment of near-universal primary school enrolment (for non-disabled children). Since the first Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS 2008-2012), Rwanda has enjoyed sustained economic growth (8% average), and the poverty rate dropped from 59% in 2001 to 45% in 2016. In the countryside, progress has however been slower and many needs regarding access to services are still not being covered. According to the 2012 Fourth Rwanda Population and Housing Census (RPHC4), there are approximately 446.500 persons with disabilities aged 5 and above in Rwanda (with a slight overrepresentation of females), representing 5% of the population aged 5 years and above. The real number of persons with disability is likely to be higher, as the World Health Organisation estimates that approximately 15% of any given population will have a disability. The same census stated that 57.213 persons are blind or partially sighted (BPS) which is equivalent to 13% of persons with disability (PWD) and 1% of the general population. In Rwanda there has been a strong political will to deal with disability issues due to the high level of disabled people emerging from the war. Rwanda has signed and ratified most of the regional and international conventions and treaties. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) and its optional protocol were ratified in 2008 and Rwanda is soon slated for a CRPD state review. The Marrakech Treaty2 is yet to be adopted, but generally there is advanced legislation in place with regards to disability, the starting point of which is a rights-based approach. A major problem is that implementation is lacking behind, but still, the international commitments adopted by Rwanda since 1998 appear to have influenced national policy strategies. This goes for the 2003 National Constitution (articles 28, 40 and 76), but also to key legislation. A central achievement for the disability movement is the Law on the General Protection of Persons with Disabilities which was adopted in 2007 (Law No. 01/2007) (referred to as the Disability Law). The Disability Law describes the state’s obligations to address the needs of persons with disabilities, in conformity with the Rwandan Constitution, which prohibits any form of

1 A detailed description of the social, economic and political situation in Rwanda, including the conditions for persons with disability, is available and can be forwarded upon request. 2 The Marrakech Treaty, initially signed and adopted by 20 states in Morocco 28 June 2013, is a treaty which allows for copyright exceptions to facilitate the creation of accessible versions of books and other copyrighted works for persons with vision impairment.

2 Danish Disability Fund discrimination. Importantly aslo, the government’s seven-year plan (2010-2017) ensures that all sector ministries make reference to PWDs and include actions to provide them with services. On an overall level, the second EDPRS 2 for 2013-2018 formally prioritises citizen participation and better service delivery. To implement the strategy, the government has developed the VISION 2020 UMURENGE (VUP). The programme has three components: direct support for the poorest households with no land or labour resources; public works employing households with labour resources to build community resources; and financial services to increase access to savings and credit and improve opportunities for non- agricultural income generation. The strategy adopts the sectors as the central implementing agency in conformity with a decentralization policy, adopted in 2001, which runs from the smallest Cell unit to the Province level. The ambition is that the majority of government programmes will be implemented by local government. This is especially true for the social service sector that includes vulnerable groups and persons with disabilities.3 Civil society organisations of people with disabilities have existed in Rwanda for about 40 years. In 2010, after lobbying by civil society, the government of Rwanda agreed to create a National Council for People with Disabilities (NCPD). NCPD is a government agency with representative structure at all levels of administration responsible for mainstreaming disability across government services and development programmes. Having a national council of persons with disabilities as a government body was a positive move by the government of Rwanda to try to get closer to PWDs. However, the Council is not always taking effective action and it also risks making it difficult for PWDs to have an independent voice to critic government service delivery to PWD. In response, civil disability organisations have organised themselves into NUDOR, the National Union of Disability Organisations in Rwanda, to serve as a coordinating and representative body for the movement and to build the capacity of member organisations. NUDOR has recently taken the lead in developing the ‘parallel report’ which will be submitted to the UN CRPD Committee in conjunction with the upcoming state review.

1.b Specific challenges faced by those groups of persons with disabilities, or their organisations, for whom the project aims to bring about change The present project builds on achievements and learning from in particular the on-going joint RUB/DAB Empowerment Project (HP 129-037, coming to a close by end August 2017) but will – following recommendations in the external evaluation of this project – focus less on member empowerment and more on strategic advocacy and building of alliances besides financial sustainability. As such the present project represents the initial step in a gradual out-phasing of the long-term collaboration between RUB and DAB. The overall problem that the project will address is continuously the general exclusion of blind and partially sighted persons from participating fully in Rwandan society. Although relevant programmes exist and the disability movement is getting better organized and coordinated, as described above, PWDs are still experiencing problems in accessing their rights and living independently. The reality they face is that the outreach of these programmes is limited and most PWDs are not reached. Instead, they have to mobilise sufficient social, economic, cultural and political resources to deal with their situation as well as they can, mainly by being empowered at both individual and family level, through disability organisations, organisations of parents or by participating personally in self-help groups.

3 Rwanda is divided into 4 geographically-based provinces—North, South, East, and West—and the City of Kigali, with the provinces being further subdivided into 30 districts, 416 sectors, 2,148 cells, and 14,837 villages (Imidugudu). Each district is administered by a Mayor, who is assisted by a team of technical staff. Districts are further divided into sectors (Umurenge), then the wards (Akagari) and then the cells (Umudugudu). At Umudugudu level, people elect a council which handles disputes, mobilizes people for community work and generally works closely with other state organisations.

Application – C: Major development project /Cooperation project – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 3 2017) D: Project of more than DKK 3 million – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 2017) Danish Disability Fund Specifically, the project will address exclusion related to the educational and socio-economic spheres; two areas which are expressed priorities for the RUB membership and where the political timing, especially as regards inclusive education, is opportune (refer further below). The lack of access to education and employment opportunities is caused by both structural and attitudinal barriers. The main, intertwined, causes are poverty; barriers related to ignorance/stigmatization among families, communities and decision makers; lack of confidence among BPS themselves; as well as the gap between legislation, implementation and disability mainstreaming as indicated above. These key problems affect PWDs from the individual to the organisational level. As regards poverty, persons with disabilities – including BPS - represented among the poorest, and primarily among the rural poor. Poverty is both a cause and a consequence of disability. Poverty causes disability through malnutrition, poor health care and dangerous living conditions. In reverse, disability can cause poverty by preventing the full participation of PWDs in the economic and social life of their communities, especially if the proper support mechanisms are not available. PWDs have typically lower educational attainment and lower employment rates than persons without disability and disability is associated with a higher probability of being poor. Households in Rwanda with a disabled member have a poverty level 1,7 percent above the national average and 76,6 percent are either poor or vulnerable to living in poverty (World Bank). Poverty also provides a huge barrier for participation in local branch or community activities since the members often cannot afford membership or transportation costs to attend meetings or hire guides. PWDs are both actively and passively excluded in Rwandan society, due to stigmatization or ignorance. PWDs are generally seen as objects of charity. Cultural beliefs and negative community attitudes are also reflected in the language used to refer to people with disabilities in Rwanda. In some rural areas, in particular, there is still little knowledge about reasons for disability. Many parents with children who have disabilities are abused and other family members look down on the parents, especially the mother and her child(ren), who may find themselves isolated from the family. Many children with disabilities are consequently hidden away.

Challenges related to access to education Both poverty and stigmatization/ignorance and lack of awareness of PWD rights among families and local communities, including school staff and local authorities, are crucial barriers preventing children with vision impairment (CWVI) from going to school and accessing education. Further, there are currently only two primary schools for the blind in Rwanda (specialized residential schools) and two integrated schools on secondary level admitting a few blind students a year. The capacity is far from near enough to cater for the many blind children that RUB identifies as part of their work in the districts.4 Over the past five-eight years, the Rwandan government has taken a number of concrete efforts to promote education for PWDs. Among these, is the National Programme on the Promotion of the Rights of PWDs (2010-2019) which details efforts overseen by the Ministry of Local Government to reinforce action to promote Inclusive Education (IE), accessibility and full participation of PWDs. Also, the current five-year Education Sector Strategic Plan (ESSP, 2013-2018) takes into account the educational needs of young people with disabilities across all educational services (teacher training and management; curriculum development etc). This is a strategy which is reflected in the Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) Policy on Inclusive Education and Special Needs (2013-2018), recently reviewed and to be approved in 2017. The latter commits the entire education sector and community at large to ensuring effective and good quality inclusive education services for learners with disabilities.

4 RUB has over the past few years ‘ by coincidence’ identified at least 30 CWVI out of school.

4 Danish Disability Fund The overall vision is that all children should go to the nearest school. However, the vast majority of mainstream schools do not accommodate sufficiently for CWVI. Apart from limited infrastructure and mobility challenges also faced by children with physical disability, CWVI need to be taught braille and there is a severe lack of trained braille teachers at all levels of education, including primary school, even if there is an on-going official process of developing an all-inclusive education at the College of Education. Furthermore, lack of accessible learning materials and equipment – i.e. educational materials in braille, audio, large print, accessible scientific materials, perkins braillers etc. - remain a serious obstacle. There is no national resource center or place where the school can get adequate materials. This means that every school, which has one or more blind children among its pupils, tries to manage as well as it can, which however is often far too little. Bullying and social exclusion of CWVI in mainstream schools are additional challenges. Therefore, if CWVI are enrolled at all, the drop-out rate is very high. In 2013, NUDOR carried out a report on the challenges faced by children with disabilities in basic education, which confirms the outlined challenges.5 Education is an expressed priority for NUDOR which is actively engaged in various activities supporting inclusive education for PWDs in Rwanda, including attempts to establish ‘inclusive model schools’, supported by MyRight in Sweden and DPOD. The project will attempt to add to this work, as will be described later. Despite the increased political efforts on promoting education in Rwanda, there remains a gap between policy commitments and the practice of inclusion in the education sector, something that has been acknowledged by the Rwandan government itself. And even if the challenges and barriers to CWVI accessing education are more or less clear, there are no comprehensive studies providing an analysis of the problem or a thorough assessment of the extent to which current Inclusive Education (IE) and Special Needs Education (SNE) policies provides for the needs of CWVI. Generally, there is a lack of quality disaggregated data and documentation in the area of disability, including on CWVI access to education.

Challenges relating to socio-economic empowerment The lack of schooling and education is one main barrier for the socio-economic empowerment of BPS and this also extends to basic skills in Orientation and Mobility (O&M) and Active Daily Living Skills (ADL)6. As many RUB members live in isolation and are never subject to demands or different exercises in coping with everyday chores, they become dependent on others to complete even the simplest tasks. The confidence in their own abilities depends on the exposure to everyday life and thus confidence levels fall. Family members often prove a barrier to community participation as they overprotect their disabled relatives and do not allow them to participate in household activities or interact with neighbours and the community in general. Also, BPS are underestimated, neglected as families feel ashamed and some even chose to reject their blind family member. The general disempowerment of BPS is a central concern and a major barrier to participation in family life, local society, not to say participating in activities of the local branch and ultimately the readiness to engage duty bearers. Rehabilitation of BPS has not been taken on as service to be provided by the Rwandan government. Currently, RUB is the only organisation carrying out rehabilitation of BPS. This is partly done at the Masaka Resource Center for the Blind (MRCB) which provides six months residential courses (training in mobility, braille, agricultural skills etc) for BPS, from 14 years of age, who have not previously been to school (MRCB is part of RUB but functions independently, refer Annex M for more information on MRCB). And partly RUB provides training in ADL, O&M and family member trainings for members at branches to the extent that finances allow. As concluded by the evaluation, RUB ‘continues to be an impressive organisation in

5 The study can be forwarded upon request. 6 The basic ADLs include eating, bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring (walking) and continence. Functional ADLs include e.g. house work, using telephone, shopping, transportation etc.

Application – C: Major development project /Cooperation project – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 5 2017) D: Project of more than DKK 3 million – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 2017) Danish Disability Fund empowering its members through training. Constant training and sensitization can change the mind-set of people in a positive way’ (Annex F, p.29, own highlight). The challenge is lack of resources to carry out the trainings, in particular since repeated trainings are needed, not least due to the low education level of members. RUB has throughout the past years tried to use other centres and institutions to provide supplementary and relevant skills to members, in particular in terms of vocational training. In Rwanda there are few vocational training opportunities for RUB members and the majority find work within the informal sector - self-employment.7 As part of the Empowerment Project, RUB has established collaboration with the government-run vocational training centre (VTC) – Nyanza VCT - and has catered for a number of trainees for them to learn to operate knitting machines. The aim has been to demonstrate that it is possible to design vocational training towards BPS and roll out the model to other VTCs. During the project, collaboration was as such established with a second VTC, the Ubumwe Community Centre. This experience, though being a first important step, needs to be further consolidated and rolled out, with a view to ensuring sustainability of both the VCT collaboration and the individual enterprises established after the training. An additional challenge in regard to economic empowerment is that RUB members are not seen as credit- worthy by mainstream finance institutions and have as such limited access to financial services.8 As part of the Empowerment Project, RUB has established collaboration with the Caritas-run, ‘Associations of Microfinance Institutions’ (RIM). The aim was, as a pilot, to facilitate access to RIM services - financial training and loan-taking – for five branches. However, this collaboration was initially coupled with a number of challenges, primarily linked to the circumstance that the selected branches preferred to make use of a Revolving Fund run by RUB for the past eight years. As mentioned in the evaluation report, RUB has therefore in a sense been competing with itself when trying to promote RIM loans (Annex F, p.7). In a preliminary attempt to resolve the situation, the services have been opened up to all RUB branches and currently three branches are engaged with RIM and two more in the pipeline. The disability organisation UPHLS9 has previously carried out a related project ‘Employable’ which aimed to support PWD cooperatives in gaining financial and vocational training, access to loans and contacts to relevant companies and employees. The second phase of the project has recently started, with a particular focus on youth with disability, and a commitment has been obtained from UPHLS that this project can be integrated with the envisioned interventions under the present project to support BPS cooperatives (more details further below). This general exclusion of RUB members from programmes implemented by both private stakeholders and government is identified as a central problem. BPS also lag behind in terms of limited access to existing official poverty alleviation programmes (the mentioned VUP Umurenge social protection programmes).10 Some sporadic efforts were undertaken in this regard under the Empowerment Project as part of local advocacy. The evaluation estimates roughly that less than half of the RUB members in local areas have had access to these programmes but systematic data has not been gathered and official data are also non-

7 There are limited employment opportunities in the public service, and the private sector is still developing in Rwanda. Also, employers are hesitant to employ visually impaired people due to fear of costs of disability compensating equipment. 8 A UWEZO study from 2014 reveals that lack of access to education and training, lack of financial resources, inaccessible financial opportunities and lack of enabling work environment, including perceptions about disability are considered to be responsible for the exclusion of PWDs from the labour market (Source: Alternative Report to the UNCRPD committee, Dec. 2016). 9 The UPHLS stands for Umbrella of Organizations of People with Disabilities in the Fight against HIV and AIDS. Even if the organisation still mainly focuses on health issues, it is slowly moving into other areas as well. 10 The VUP includes a number of programmes, including a number of relevance to BPS; e.g. HIMO; provision of intensive short term employment for the very poorest, organized at sector level – and Ubudehe; small grants paid out at village level to both individuals and groups (refer Annex O).

6 Danish Disability Fund existing. The lack of data on the prevalence of blindness in the country also contributes to lack of interventions towards BPS in Rwanda. Local authorities are often not aware of BPS in their districts. To a large extent, inclusion in the various programmes depends on decisions made at Umudugudu level; however decision makers are not always sensitized to the rights and abilities of BPS, and the BPS may not have the knowledge or confidence to voice their concerns in the appropriate fora.

Challenges relating to organisational capacities Organisationally RUB has reached a point where it is ‘at several levels’; i.e. its 57 branches are at different stages and levels of capacity. Some branches are quite new or still weak in terms of capacities, while others have operated for a long while and are quite advanced with a well-functioning leadership, hold regular meetings and plan activities together and may have established cooperatives making them eligible for more government support.11 The evaluation of the Empowerment Project - which aimed to strengthen the organisational capacity of 30 branches - concludes that local leadership is being built, albeit slowly (Annex F, p. 9). In the weaker branches, the interaction of local RUB branches with both public and private stakeholders is limited and RUB members are not always aware of local stakeholders present in their community or how to target them. Therefore, even if improvements have taken place, the majority of the branches do not work strategically towards integration and inclusion in the community. Generally, members identify themselves with RUB and the goals of the organisation, and there is a relatively strong link between RUB and its members, in large measures because of training activities, MRCB trainees and outreach visits. However, as also confirmed by the evaluation, the staff of RUB are ‘stretched thin’ with many tasks assigned and required regular field visits to the many branches to support and monitor developments. Gathering of data from the field has been systematised in the course of the Empowerment Project and is working pretty well. However, the data are still not systematically consolidated, analysed and used for awareness and advocacy, and generally advocacy capacities at both local and national level are still insufficient. A small advocacy fund was set up during the Empowerment Project to support local initiatives; however, as noted by the evaluation, many of these have focused on solving individual cases regarding access to school, shelter or difficulties faced by isolated members, rather than influencing local policies. At national level RUB is part of all relevant networks and is recognized as a key stakeholder in the disability movement. In 2015 RUB developed a two-year advocacy strategy (2016-2017) with the support of VSO but this has since not been systematically followed, e.g. due to lacking resources, and it needs an update. The evaluation of the Empowerment Project concludes that advocacy is still the newest area for RUB and the efforts are too scattered and too focused on events and individual cases rather than on promotion of policy changes (Annex F, p.27). RUB has a sub-committee on advocacy which is meant to guide and support efforts in this regard. In December 2016 the sub-committee was re-constituted in connection with the RUB General Assembly so most of its members are new. The same goes for the board, and even if most members hold an education, their experience on particularly national level advocacy is limited. The same applies to fundraising which is another area where capacity building is still low. RUB has continuously tried to seek new partnerships and donors but progress is limited despite generally positive working relationships with government and public institutions. At local level, branches have been relatively successful in attracting small scale and in-kind support, and at national level in 2016 RUB managed for the first time to obtain public support for 30 students at MRCB from the Rwanda Governance Board (RGB) but

11 Establishing a cooperative demands a considerable financial input on the part of the members of the cooperative which prevents the majority of RUB branches from obtaining this status.

Application – C: Major development project /Cooperation project – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 7 2017) D: Project of more than DKK 3 million – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 2017) Danish Disability Fund unfortunately a repetition of this support seems unlikely. Currently, RUB relies heavily on primarily two donors (SIDA and Danida) and is in lack of a clear strategy on how to diversify their funding base.

2. WHICH EXPERIENCE AND RESULTS DOES THE PROJECT BUILD UPON? (suggested length: C applications 2-4 pages, D applications 3-5 pages)

2.a Previous cooperation experience with the partner RUB and DAB have been working in partnership since 1998 and consider themselves sister organisations, who share values, experiences and learn from each other in terms of developing inclusive organisational structures and through working towards equal opportunities for blind and partially sighted persons. DAB considers RUBs leadership as a resource on rehabilitation and education for the blind and utilise their skills and experiences in other areas of DAB’s development work. Likewise, RUB and DAB leadership have jointly worked for the development of African Union of the Blind which is the regional body uniting blind organisations in 50 countries across Africa and where the RUB leadership previously was represented on the board. The partnership has throughout the years moved from small specific instrumental support through minor projects and lately to more complex bilateral projects. The interventions have primarily been supported by Danida, initially through CISU (Mini-programme) and since then the Disability Fund. The three most recent projects are the following: Jan 2010 – Dec 2012 ‘Outreach Project – organizing blind citizens in Rwanda’ (MP 09-722) Jan 2013 – Feb 2014 ‘Wisdom is our Dignity’ (Jan 2013 – Feb 2014) (MP 302) Mar 2014 – Aug 2017 ‘Empowerment Project’ (HP 129-037) As regards the contents of these projects, this has developed accordingly from an initial main focus on community engagement and establishment of new RUB branches (geographical outreach), towards an increasing focus on branch strengthening, through a ‘standard package’ involving various training, support to awareness raising and advocacy. The latest Empowerment Project has further piloted interventions related to vocational training, income generating activities and legal support to human rights violations. Empowerment of members and families – through rehabilitation and training – has been a continuous priority, perceived both as an end in itself and as a means towards building a strong democratic organisation.

2.b (and 2.e) Results and learning The learning and positive changes achieved through the on-going Empowerment Project, as documented in project progress reports as well as the final evaluation report (Annex F), have significantly influenced the choice of intervention areas and strategies in the present proposed project. At an overall level, the evaluation report concludes that the strategy and activities based on empowerment, organisational development and advocacy have been relevant and could be continued if in conformity with RUBs strategies. It is confirmed that individual empowerment and organisational development is a precondition for attending to the needs of BPS; strengthening the organisation is necessary for strategic orientation and in order to undertake advocacy activities which in turn is necessary for BPS to lay claim to their rights (p. iii). Following the outline in chapter 1.b., the main results and areas of learning comprise the following: Training and social empowerment of members and their families can and have contributed to significant positive changes in people's lives. This is primarily due to RUBs long and valuable experience in this area and is valid both as regards the residential training courses at MRCB and the four days ADL trainings. The

8 Danish Disability Fund ability to participate in daily activities, household decisions and community activities in turn creates respect with family members who on their part have also gained better understanding on BPS issues and capabilities through the important family member trainings. However, for future it will be important to motivate those who have been trained to go on to train other and new members. The same goes for the family member trainings (p.26). The MRCB graduates become active in branches upon their return and approx. 70% become involved in livelihood activities. Thus, as the trainings initiates both a more active life and improves relations and generates more confidence and trust in other people, gradually the social empowerment can potentially connect to economic empowerment. In terms of economic empowerment the RUB revolving loans have worked well and have served to trigger income-generating activities such as rearing of pigs and cows, buying and reselling crops etc. This proves that branches are indeed able, with guidance and support, to manage loans and carry out small-scale IGA projects (p.17). However, since the loans have shown to be an obstacle for the collaboration with RIM, as mentioned above, the revolving fund should be adjusted, and an alternative found which will allow for greater sustainability and broader reach since the revolving funds would never be able to meet the full demands. The partnerships established with the two vocational institutions seem to carry great potential. The experience is that the vocational training is an effective way of empowering BPS as this has added to motivation and change of mentality from receiver of charity to someone who can contribute. As an example, experience shows that trainees often by own initiative train others when returning to their branches. But also here, efforts are needed with a view to monitoring and ensuring sustainability of the interventions both in terms of the costs implied and the established livelihood activities. With regard to organisational development and strengthening of local branches, trainings and activity/follow up support have generated positive changes in the sense that branches plan activities together such as savings and livelihoods. Organisation of sports activities at branch level is currently being tested by RUB as part of the final phase of the Empowerment Project. The experience from other countries, including Ghana, is that this is an effective way of mobilizing members and creating awareness. Also, piloted exchange visits have been much appreciated and inspired learning and new branch activities. The capacity building and outreach to branches are important in terms of consolidating the strength and cohesiveness of RUB as an organisation (p. 9). About 2/3 of the capacitated branches draw up agendas and plans for the work and report back to RUB in Kigali in the form of written quarterly reports. However, a common format could be useful in order to collect the same information at branch level (p.10). As earlier indicated, a system at national level is also needed to consolidate information and use of this for broader purposes. The lack of consolidation and analysis may partly be due to the fact that the geographical reach in the Empowerment Project has been very wide (39 branches) which suggests that the scope has been too broad in particular in view of limited staff resources available (p. 10). As described further above, advocacy has posed challenges. However the training on human rights have led to increased knowledge and self-confidence which has led members to confront community members who have not treated them properly (p. 12) and branches have raised cases of rights violation on several occasions, especially as affecting women.12 Even if, as mentioned, the small scale advocacy funds have focused too much on individual cases, still the activities have added to significant awareness raising in the local communities and have helped open doors and strengthen relations with local authorities and other duty bearers though any tangible results have not been systematically documented. For future, RUB should focus more on promoting and documenting access to social protection government programmes under VUP (e.g.p.vi). Further, the monitoring of the funds have taken up many resources from RUB national level

12 Piloting of (legal) support to address human rights violations formed part of the Empowerment Project. Even if small important results have been obtained, this activity will not be continued as part of the DREAM project due to a concern that scarce resources may be spread too thinly. Instead separate funding will be pursued for a continuation and further expansion of this work which is still considered of great importance.

Application – C: Major development project /Cooperation project – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 9 2017) D: Project of more than DKK 3 million – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 2017) Danish Disability Fund which all in all suggests a closer look at how these funds are used and monitored. Further, national level advocacy could benefit from a closer strategic link to developments at local level besides closer coordination and collaboration with NUDOR which at least in one instance has led to an important result in terms of obtaining tax exemption for assistive devices. The same goes for fundraising (ibid). According to recommendations in the evaluation, advocacy should focus on national education policy and follow up on the parallel report-writing (ibid). RUB is experienced and strong regarding raising awareness on blindness issues (p. 15), both at local and national level. Through organisation of campaigns and similar activities, RUB has managed to access and attract good media attention, and these activities are considered of utmost importance by RUB itself in terms of visibility and recognition. RUB has further managed to introduce a high degree of sensitiveness towards gender issues, e.g. through insisting on gender-balanced participation and involvement in project activities. Also, women have worked together, through the formation of women committees, and have used savings from funds to buy animals which is a good first step for women towards economic empowerment (p.27). RUB does not have a gender equality policy but plans are to develop this in 2018 with support from the Swedish blind organisation (SRF), and this can help to inform any relevant adjustments to the present project. In summary, the challenges, results and learnings of earlier project interventions, suggest a new project – more focused in geographic and thematic scope - which continuously will build on the successful empowerment of members, not least for the purpose of organisational strengthening and in order to generate ‘evidence’ which can feed into awareness and advocacy efforts. Further, the training of members should be carried out with greater view to sustainability, e.g. through the testing of training of trainers (ToT) as a new approach to build member empowerment. More emphasis should be put on exploring avenues, testing intervention models and building sustainable strategic alliances with regard to supporting and mainstreaming economic empowerment of members. And finally, findings call for strengthening of advocacy at both local and national level, with a strategic focus on access to education, as well as increased focus on financial sustainability.

2.d (and 2.c)13 Assessment of partner capacity RUB holds long-term experience in regard to implementation and monitoring of development projects in collaboration with both local and international donors, which besides the Danish support in particular concerns support from SIDA through SRF. As documented by an OCTAGON organisational assessment carried out by SRF (Annex G), RUB has all relevant internal regulations and policies in places (except the above-mentioned gender policy). RUB’s overall organisational strategy is outdated but will be revised in the inception phase of present project in collaboration with SRF. The same goes for the existing advocacy strategy. RUB’s internal regulations also include sound financial procedures which are followed systematically and meticulously by RUB staff and which have not given cause to concern as regards the management of the on-going Empowerment Project. This project is of a similar budget size in DKK as the present proposed project.14 As indicated above, the evaluation has found that RUB staff has been stretched as compared to the wide scope and amount of work in the Empowerment Project. Consequently, it is suggested that RUB should consider making use of volunteers to a greater extent. RUB already has a roaster of volunteers (besides a volunteer policy) and systematically tries to make use of these whenever possible. However, due to low levels of education as well as the need for guides etc., there is a limit to how much RUB can rely on volunteers and to what degree this will actually relieve staff of any work. As a consequence, it has been

13 Chapter 2.c in the application format (‘Challenges’) is covered partly in chapter 1.b and partly in this chapter 2.d. 14 Due to the current strong dollar, the budget size in USD/RwF is actually considerably smaller than the previous project.

10 Danish Disability Fund instead been decided to narrow down the number of targeted branches and districts (refer chapter 3.b and Annex H). Furthermore, in December 2016 the RUB board and sub-committees were reconstituted, and the majority of the new members are educated and competent. It is therefore expected that board and sub-committee members can add positively to the project goals, not least within advocacy and IE, since three members are experts within this field (ToR for sub-committees are currently being reviewed to this effect). Further, two members are employees at NUDOR which also speaks well for the envisaged concerted efforts on the same two areas. Limited strategic advocacy skills – and monitoring to assist advocacy - were indeed singled out in the evaluation as one of the weaknesses of RUB, and DAB will therefore, as suggested, ‘freshen up the technical part of the partnership’ and work closer with RUB on this area. The same applies to, as also recommend, fundraising efforts. The increased project focus on these particular areas - advocacy and financial sustainability – thus reflects the current capacity challenges of RUB, and is a key stepping stone in the mentioned gradual out-phasing of the project collaboration between RUB and DAB.

2.f Preparatory process As mentioned, the present proposal is to a large extent based on the findings and recommendations of the evaluation of the Empowerment Project, generated through interviews held with members, RUB executives and local authorities. The findings and recommendations were initially discussed at a RUB retreat (with selective staff, board, sub-committees members) in February 2017 which triggered much of the thinking behind the design of the project. In early March, DAB and RUB met to further discuss the three mentioned intervention areas, their respective targets and strategies to be applied. A half day workshop were in this connection held with the board and sub-committee members in which the main components were agreed upon and which provided important insight into needs, challenges faced and strategic windows of opportunities within the various areas. Meetings were also held with NUDOR, UPHLS and MyRight Rwanda to discuss coordination and collaboration on related activities. RUB has subsequently further explored the options for integration of project activities with the mentioned organisations, in addition to Handicap International, and this has resulted in confirmation and clarification of collaboration within the areas of access to education (NUDOR and HI) and economic empowerment (UPHLS). The actual drafting of the proposal has taken place in close collaboration between RUB and DAB. Close reference has been made to a draft proposal for RUB and SRF collaboration (funded by MyRight) for continuous project collaboration (to begin Jan 2018 if approved), supplemented by skype meetings between SRF and DAB staff. The mentioned OCTAGON organisational assessment, carried out by SRF in 2014 with follow up on status in December 2015 and 2016, has confirmed the main organisational strengths and weaknesses and helped inform the interventions in this regard (Annex G). This is in line with one of the recommendations of the Empowerment evaluation which emphasized more active coordination between DAB and SRF on issues such as capacity building, joint project content etc. The present project and the SRF proposal plan to carry out similar activities in regard to assisting CWVI to schooling, but in different districts. Data and learning from the collective districts will feed into advocacy carried out under the present project. Further, a number of activities relating to organisational development, including update of the mentioned RUB strategy and organisation of board/subcommittee meetings are co-funded (refer Annex B). The Rwanda parallel report on CRPD report (draft finalised in December 2016 following a process led by NUDOR) has further informed the choice and priority of strategic advocacy areas and will be used actively throughout the actual project implementation.

Application – C: Major development project /Cooperation project – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 11 2017) D: Project of more than DKK 3 million – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 2017) Danish Disability Fund At the Danish level, the process of development of a joint country strategy for Rwanda, embracing the Danish disability organisations active in Rwanda, has been helpful in terms of clarifying contextual issues as well as the priority areas, not only of RUB, but of the disability movement in general in Rwanda. As such the process has also helped identify areas of mutual concern and potential for joint advocacy interventions, and has informed the selected intervention areas of access to education (outcome 1), social and economic empowerment (outcome 3) as well as organisational development (outcome 3); all identified as priority areas in the draft country strategy.15 Finally, the decision by the Danish disability organisations, headed by DPOD, to pursue the possibility of having inclusive education for CWD selected as the theme for the ‘DR Christmas Calendar’ and the potential synergy and increased impact that this could bring, has confirmed the focus on inclusive education in the present application.16

3. WHAT CHANGE WILL THE PROJECT ACHIEVE AND HOW? (suggested length: C applications 8-10 pages, D applications 10-14 pages)

3.a Change (max. ½ page) This project seeks to ensure that RUB has manifested itself as a strong advocate and the legitimate ‘go to’ organisation for external stakeholders in matters related to BPS issues. The idea is to create learning models for how to include BPS persons in education and socio-economic activities. This means that CWVI and their families will have an understanding of their rights and the importance of the children receiving an education. Further, it means that RUB members can actively participate in governmental programmes or run their own profitable businesses. The learning models will build on the experiences from activities and support RUB in further establishing its ‘brand’ as a spokes organisation for BPS persons. On a more institutional level, RUB will as an organisation further build its own capacity to advocate towards national stakeholders, such as government institutions – and other service providers – to ratify and implement national and international policies advancing the rights of PWD; in particular the IE policy and the Marrakech treaty. This means there will be significant positive changes to the lives of the individual beneficiaries of this project as they partake in testing the activity approaches and further consolidating RUB as a strong sustainable organisation, and on a larger scale, learning models will be established which can be used in future advocacy and in relation to rolling out similar initiatives in other districts across Rwanda.

3.b Stakeholder analysis (which stakeholders are relevant to involve in the project and how?) and target groups (among whom will you achieve change?) (1-2 pages) The target groups described below are the main stakeholders in the project. However, a number of external stakeholders are identified as influential towards the success of the project. These groups can be classified under three headings; 1) national and local governmental stakeholders (in particular educational and employment authorities), 2) NGOs and other allies (including not least NUDOR, VTCs, UPHLS, RIM), and 3) potential partners and donors. For more details, refer to Annex D. Some of the key external stakeholders also form part of the primary target group as will be apparent below. The primary target group, who will participate in project activities, is made up of:

15 The process of developing the country strategy has involved workshops in both Denmark and Rwanda, involving four disability organizations in Denmark and six in Rwanda. The strategy will expected be valid as from January 2018 at the latest. 16 A joint concept note on ‘Børnenes U-landskalender’ submitted in early February was unfortunately rejected by Danida; however plans are to submit a revised proposal early 2018 for the calendar project in 2019.

12 Danish Disability Fund - 453 RUB members who will participate in project activities at district level. These are registered members and leaders of RUB in 15 branches spread across 12 districts of Rwanda. They will be personally empowered through various trainings, follow up visits and guidance, access to small scale advocacy and awareness raising funds, and events financed by the project. An equal gender distribution will be sought when implementing project activities.

- 300 family members who ill be educated on the rights, needs and capabilities of BPS. These will in turn pass on their knowledge to other family members. - Estimated 300 government officials at district (270) and national (30) level will also participate in project activities as a separate primary target group. District officials will mostly be selected staff and members of social welfare offices, educational and school authorities. At national level they include ministry officials and members of the NCPD. They will participate in orientation sessions, dialogue and sensitization meetings, enabling them to better exercise their duties.

In addition a number of specific groups are targeted under each of the three identified overall areas of intervention, i.e. education, socio-economic empowerment and organisational development. There may be some overlap with the RUB branch members mentioned above:

- 71 CWVI in the 12 districts will be assisted to go to school. 15 of these (living in four ‘NUDOR districts’, refer Annex H and below) will receive special support and assistive devices which will make it possible for them to enrol in a ‘model school’, and 56 CWVI (from the remaining eight project districts) will be assisted to access some kind of schooling, whether public or private. - 110 BPS will undertake a 6-month rehabilitation course at Masaka Resource Center for the Blind (MRCB). 15 of these will be selected for special training on how to train others (ToT) when they return to their home branches. The MRCB trainees are selected on an individual basis and may come from outside the project branches. - 45 BPS who will participate in vocational training (knitting, massage etc.) at a vocational training centre. Like in the case of MRCB, they may be selected outside the project branches and some may be former MRCB trainees. - Estimated 210 branch members in 7 branches will benefit from accessing RIM services and loans with a view to establishing IGAs. Moreover, estimated 20 individual RUB members (previous VTC trainees, or MRCB graduates) will access RIM services, in addition to estimated 40 youth branch members in four branches who will benefit from establishment of cooperatives and integration in UPHLS ‘Employable’ project. - Staff of RIM, VTC and other potential strategic partners at district and national level also form part of the primary target group. These will be invited to participate in partnerships and various forms of collaboration with RUB for mutual benefit. It is difficult to pre-estimate the figures for this group. - Finally, 28 BPS at national level (board members and subcommittee members) will participate and benefit from training to strengthen their skills on advocacy and organisational issues, in particular fundraising - in addition to 6 RUB staff who will increase their skills on particularly advocacy and fundraising.

The secondary target group, who will benefit indirectly from project activities, embraces the following three groups: - Estimated 90 additional BPS in the 12 districts (members in non-project branches) who will benefit through involvement in district activities, increased access to government services and higher awareness on blindness and disability issues.

Application – C: Major development project /Cooperation project – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 13 2017) D: Project of more than DKK 3 million – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 2017) Danish Disability Fund - Family members of BPS (beyond the ones directly engaged in family member trainings) who can be expected to benefit from either a personally empowered or materially benefitted PWD member. Using the average household size of 4,6 in Rwanda, the number of people involved would be about 1700 persons. - The local communities of the 12 project districts that will be engaged through local advocacy and awareness raising activities. The ultimate target group of this project are the estimated 22.000 individual BPS making up the total BPS population in the 12 project districts17 who as rights holders will benefit from having more responsive government services in their district and better acceptance of BPS in local society. The general membership of RUB nationwide – total 2500 BPS - will in the longer run benefit from having the support of a more efficient, more capable, better known and better funded organisation.

Social composition of the participants and beneficiaries Though most BPS in Rwanda can be described as marginalized (refer above, 1.b), BPS are not a homogeneous group but can be categorized into at least three broad groups who in different ways are targeted and benefit from the project interventions: a. Resourceful and empowered (about 5 % of the BPS population).18 This describes those who have been through formal education/training/apprenticeship to the level that they are employed, self-employed or have a regular source of income. Members of this category tend to be active in RUB and are often elected to hold positions of responsibility. In the projects, activities targeted at this category include; training on human rights/advocacy, leadership and programme management training, access to RIM services (IGAs), vocational training, and advocacy and awareness raising funds. b. In need of empowerment (about 5% of the BPS population). This describes members of the organisation that may have had some basic education/training/apprenticeship that enables them to survive but not thrive. BPS in this category tend to attend meetings and vote for the more resourceful and more educated to take up leadership positions within RUB. In the project, activities targeted at this category include; family member trainings, ADL training, human rights/advocacy trainings, participation in branch/sports activities, and access to poverty alleviation/social protection programmes. c. Marginalized (about 90% of the PWD population). This category refers to those BPS who are the most vulnerable. Most of them do not have any reliable economic activity to live on and depend on hand outs and charity. Though some of them may occasionally find some work for pay, it is usually transient and poor paying. In the project, activities specifically targeted at this category include: rehabilitation at MRCB, ADL training, and access to schooling and poverty alleviation programmes. As mentioned the project will target its interventions in 15 branches across 12 districts. Reflecting the described variation in levels of capacity of branches (refer chapter b.2), the target branches are composed of five ‘A branches’ and 10 ‘B branches’, each comprising the described three groups of BPS, however with relatively more members from category a and b in the A branches. Besides reflecting the varying capacity of branches, the rationale behind the selection of the two types of branches is an attempt to exploit the potential relating to peer support and cross-learning. For further details on the branches including selection, refer to Annex H. The challenges and potentials of the respective branches and districts are guiding the strategic approaches that will be applied, as will be further described in the strategy section below.

17 This number is based on the 2012 census estimate of a total 57.213 BPS spread across the 30 districts of Rwanda. 18 The percentages given are estimates by RUB. The members of the categories are not static and there is quite a lot of movement especially between the second and third category.

14 Danish Disability Fund

3.c Objectives and indicators (attach a logframe) Reference is made to the attached logframe (Annex C)

3.d Strategy (suggested length: C applications 5-7 pages, D applications 6-9 pages) The project is a continuation of previous joint efforts between RUB and DAB aiming to strengthen RUB as an organisation capable of empowering its members and advocating for the inclusion of BPS in Rwandan society. Previous projects have primarily focused on raising awareness of BPS conditions and capabilities and on capacitating and supporting members and RUB branches as a means to building the organisation. In contrast, as earlier indicated, the present project will apply an increasing focus on advocacy for the promotion and realization of BPS rights and opportunities, as well as on financial sustainability. As such the project constitutes the next logical step in the previous string of efforts. In line with this, the identified first two project outcomes are advocacy related, addressing lack of access to education and lack of social/economic inclusion respectively, whereas the third outcome concerns organisational and financial strengthening. These three areas are all singled out as priorities in current RUB strategies, and, as mentioned, are also specifically mentioned in the evaluation of the Empowerment Project as strategic areas to be pursued further. As indicated further above, RUB has not previously been intensively engaged in promoting education for BPS but has attempted, within the limits of existing resources and when coming across CWVI out of school, to assist these to some kind of schooling, whether public or private. However, access to inclusive education for CWVI is currently on the political agenda in Rwanda due to a recent review of the IE policy and the upcoming CRPD state review, and timing is therefore opportune. The overall change logic underlying the present project is that it is an obligation of the state and other duty bearers to ensure a society inclusive of BPS but that this will only be informed and brought about by a strong viable organisation of the blind, which is based on empowered and capacitated members and is working hand in hand with the other disability organisations in Rwanda. Or put differently, members - when capacitated, mobilized and represented – can build a strong legitimate RUB (outcome 3), that is able to effectively raise awareness and advocate for services and are enabled to hold duty bearers accountable (outcome 1). Likewise, a strong RUB that is visible in delivering results for BPS and in empowering BPS as productive members of society (outcome 2), can motivate empowered members to contribute actively to the organisation, and can also make RUB valuable to duty bearers, donors and sponsors seeking to engage BPS as constituents, partners, or clients (outcome 3) – in turn strengthening and supporting the situation of the members. As the logic indicates, and will further be described in the below, these intervention areas do not stand alone but are mutually supportive and collectively address the plethora of barriers and challenges mentioned in chapter 1.b. A main project assumption suggests that tested models of intervention and individual role models and success stories will help change perceptions and convince local communities and political and private decision makers alike, that BPS are indeed capable and able to contribute to local communities and society at large. This will in turn help fight exclusion. Changes of behaviour among the key groups (BPS persons, duty bearers/service providers and community stakeholders) are central to the project goal and run through each of the three project outcomes, as mentioned focusing respectively on 1) access to education, 2) socio-economic empowerment and 3) organisational strengthening (including financial sustainability):

Application – C: Major development project /Cooperation project – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 15 2017) D: Project of more than DKK 3 million – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 2017) Danish Disability Fund Outcome 1 - Access to Education: Education authorities (at national and local level) are motivated and have begun transforming policy into inclusive institutional practice benefitting CWVI beyond the target group Collectively the projected interventions under Outcome 1 aim to address the mentioned challenges relating to lack of awareness and knowledge on CWVI, lack of quality training and accessible equipment, and lack of data and documentation. Through sensitization, provision of expertise and support, and building of alliances, the project will generate learning and documentation which in turn will be used for advocacy at both local and national level. The project will feed into the on-going efforts of NUDOR to establish ‘inclusive model schools’ ensuring inclusion of CWVI in these schools for a more comprehensive model, since currently only children with physical disability (and partly intellectual disability) are targeted. The model will inform the implementation of IE/SNE policies on a medium to long-term basis, while elements may still be relevant in public schools without a specific IE policy on both short and long-term. In addition to the work on model schools, the project will carry out less intensive interventions in other districts to generate learning on minimum requirements for meaningful social and academic integration of CWVI in mainstream schools. The general logic is that more CWVI will attend and retain in school if parents, school authorities and relevant community stakeholders are sensitized to support CWVI, and if tangible evidence and tested models are presented to raise duty bearer awareness and willingness to adopt conducive policies and to transform these to practice. The concrete strategic interventions to be pursued under this outcome fall under three main headings as follows: Assisting CWVI to school – testing of interventions In the four project districts which overlap with the districts in which NUDOR works to establish inclusive model schools (refer Annex H), the project will undertake supportive actions to identify CWVI out of school, sensitize the families and school authorities, as well as facilitate that the specific needs of the children are assessed and catered for (refer below). This latter will also include to engage, in collaboration with NUDOR, the Rwanda Education Board (REB) to deploy teachers who know braille to the schools. Close monitoring and follow up will be done with the children, their families, teachers and the school authorities. In the remaining eight districts, RUB will likewise identify children out of school and in these districts engage parents, school authorities and district leaders in a dialogue on the right to education and how the children may be assisted to some kind of appropriate schooling. As earlier noted, in collaboration with SRF, RUB will expectedly from 2018 be carrying out similar activities in six branches in three additional districts In both types of districts, family member trainings (refer Outcome 2) and capacitation of branches (refer Outcome 3) will support the interventions. The branches and RUB volunteers will be actively engaged in identification of children, monitoring and follow up, and in gauging support from the local community. As indicated, the aim, besides assisting the children to school, is in particular to generate learning and documentation on adequate modes of intervention to support CWVI to access and retain in mainstream school. An expert study, to be commissioned by RUB, will be carried out in the early phase of the project period to supplement the mentioned NUDOR study in order to collate and systematize knowledge and information with a view to informing detailed strategic and targeted project interventions (draft TOR in Annex L). Data and best practices, to be gathered in the course of the project from all 12 project districts (also using data from SRF districts) will supplement this information. A simple registry will keep track of the involved children to follow developments and capture learning. A small handbook summarising best practices on the integration of CWVI in ‘ordinary’ schools will be shared with all 57 RUB branches and education authorities at cell, sector and district level.

16 Danish Disability Fund Assessment of CWVI needs and access to assistive devices A separate target, partly a prerequisite to the interventions outlined above, is to develop and test a model for the (vision) assessment of the CWVI and their specific needs in order to clarify and document what needs to be in place for them to attend mainstream schools and to perform on equal basis as non-disabled children. This will be carried out in close collaboration with Handicap International which, backed by Unicef, is already engaged in related work, including as part of the NUDOR/DPOD project. RUB will in collaboration with HI seek additional strategic alliances and potential sponsors who may facilitate access to equipment and accessible educational materials in the project districts and beyond. Influencing duty bearers RUB’s current advocacy strategy will be revised within the first six months of the project (refer Outcome 3), and will include a detailed sub-strategy on access to education drawing on the results of the mentioned study. Main priorities will relate to the lack of trained SNE/IE teachers (including braille) and the lack of accessible materials and equipment; both also highlighted in the CRPD parallel report as areas of general concern across the disability groups. The REB is one main stakeholder which will be engaged with a view to identifying sustainable mechanisms. Strategic and evidence based advocacy, making use of gathered data and learning, will be carried out in close collaboration with NUDOR and the NUDOR Steering Committee on Education, which RUB is currently chairing. On the RUB board/Women sub-committee are two university professors and one teacher who will serve as special resource persons. Besides the two mentioned priority areas, RUB will also make a petition and carry out advocacy to convince the Rwandan government to ratify the Marrakech Treaty. RUB has already initiated this work with the support of the Ecumenical Disability Advocates Network and if ratified, this will serve to support the access to accessible educational materials at all levels.

Outcome 2 – Social and Economic Empowerment: RUB members have been socially and economically empowered through rehabilitation/training and increased access to services and government programmes. Knowledge has been consolidated on viable avenues for economic empowerment for BPS. The interventions under Outcome 2 build upon the experience, learnings and partnerships established as part of previous projects. The aim with this outcome is to consolidate existing strategic partnerships while trying out new venues for social and economic empowerment of BPS. Besides supporting the inclusion and livelihood of selected RUB members, who can serve as positive role models and examples for stakeholders and other BPS, the broader strategic aim is to generate, evaluate and document learning on the various barriers and in particular opportunities for socio-economic inclusion and empowerment of BPS which can be used for further mainstreaming efforts. Inclusion as active members of society is a key factor under this outcome but in recognition that not everyone will become an entrepreneur and run a business, efforts will be made to promote that BPS are included in poverty alleviating government programmes on the same terms as non-BPS. That said, many BPS do hold potential and some basic capacities and it is assumed that they, with more vocational skills, will be able to become active contributing members to their community. To be able to get this point, though, not only the BPS needs to know more about the vocational opportunities, but the stakeholders and service providers also need to be more aware of the capacities of BPS. The experience and logic is that this will create a mutual recognition between the community members and BPS and this will support, not only the economic empowerment of BPS as they can earn their own living, but also their social status in their community. It is expected that this will show BPS themselves and their surrounding communities that they can contribute actively in their communities. The concrete strategic interventions to be pursued under this outcome fall under three main headings as follows:

Application – C: Major development project /Cooperation project – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 17 2017) D: Project of more than DKK 3 million – DANISH DISABILITY FUND (Jan 2017) Danish Disability Fund Active participation in households and local communities Change starts with RUB members themselves changing their mind-set and becoming active in overcoming attitudinal, institutional and physical barriers that may be present in their communities. As earlier mentioned, participation and contribution in household and community activities brings social recognition and is an important part of the empowerment process. Also, this is crucial for the communities’ perception of what BPS are capable of. The evaluation of the Empowerment Project confirms the impact of the rehabilitation and family training as it dramatically changes people’s lives and needed to get members out of isolation. The training is a precondition for any other economic empowerment initiatives, organisational training and, at a later stage, advocacy efforts. The individual capacity building will be based on training in ADL (for 10 B branches) as well as the rehabilitation course at Masaka, which also includes a start-up kit for the graduates e.g. pesticides, farm tools or a pig or goat (refer Annex Q). As a new approach, the ADL training will be carried out as a ToT training, so that instead of training all branch members, only 1/3 of the members will be trained and will collectively be charged with the responsibility of training the remaining branch members. The same applies partly to the MRCB courses where, as a pilot, 15 MRCB trainees will be selected to undergo a special ToT component as part of the MRCB course. The idea is that MRCB graduates become instrumental in their local district branches in regards to identifying and teaching new members in ADL and O&M, and in developing activities in the branches. In contrast to previously, the selected MRCB trainees will systematically be encouraged and trained in how to engage in peer education and will be assisted to deliver what they have been taught upon their return to their branches. This will include support to follow up and cross learning. As described in chapter 1.b, families continue to be a barrier to members’ independence due to overprotection and underestimation of the capabilities of the blind. RUB will continue to work to raise the awareness in families and communities about disability rights and capabilities of BPS to ensure that relatives are well abreast with issues pertaining to blindness. Each branch member is invited to a family training workshop together with a family member (in 10 B branches). A key lesson learnt from earlier is to ensure that the participants are decision makers in the family and to build in a commitment to repeat lessons to the rest of the household. The trainings will have a special focus on access to education where CWVI are concerned (refer Outcome 1). An extra benefit from the family trainings is awareness raised as the local communities gather as spectators when practical exercises are arranged (e.g. guide techniques and walking blind folded). Refer to Annexes I, J and K for an overview and details on the trainings. Economic empowerment The project will continue to consolidate the established partnership with RIM which will target its effort towards 5 A and 2 B branches (the latter following branch trainings under Outcome 3) as well as MRCB graduates and VTC trainees (refer below). In order to qualify for a loan, loan takers need to have a bank account and to prove their skills by previous small IGA activities. RIM provides training for loan takers in project and financial management. The catholic based association is present in every parish and also does follow up on loan takers to minimize loses which is why RUB continuously sees RIM as the best partner in this field. As mentioned in chapter 1.b, the initial efforts in promoting access to financial services under the Empowerment Project experienced some difficulties but have recently been gaining momentum. To further support this, RUB will over the coming three years gradually phase out the loans under the RUB revolving fund. Consequently, only branches not previously receiving a loan will be eligible with the exception of some of the weaker branches which may get opportunity for a second loan. Through this out-phasing and the general increased focus on consolidating partnerships with mainstream service providers who can provide technical support to the beneficiaries, RUB will gradually be able to move away from a (potentially) conflicting role as a credit/service provider to the membership itself and towards more sustainable venues for member empowerment.

18 Danish Disability Fund Gradually, the revolving fund can be transformed into ‘guarantee funds’ which are set aside as a guarantee to RIM provided that loan takers do not repay their loans. Experience shows, also from DAB project in Ghana (HP 115-124) that financial institutions show a higher degree of willingness to include BPS, when the potential risk is removed from the financial institutions’ engagement. Thus it is also a purpose in itself to show to RIM and other institutions that BPS represents a potential business opportunity, as they are credit- worthy to the same extent as any other persons. The workability of this approach is currently being tested in the mentioned project in Ghana and results look promising (for more details, refer to Annex N). As a new approach, a partnership with UPHLS will ensure the integration of RUB cooperatives in four districts into the mentioned ‘Employable’ project of UPHLS assisting the start-up of businesses and linkage to relevant companies. In terms of setting up small enterprises through the loans, RUB will as part of branch trainings and follow up visits (refer below and Outcome 3), guide and support loan taking branches and individuals in engaging with local communities (market queens, traditional leaders, local authorities etc.) for their support to established IGAs. RUB will further encourage and support trained members to engage with agricultural companies (such as IKIREZI) and others relevant companies.19 Rwanda’s economy is agriculturally based and subsistence agriculture is also the main source of income generating activities that RUB local branches engage in. RUB will also continue the two partnerships established as part of the Empowerment Project with the government-run VTCs, Nyanza and UCC. The centres will continuously admit BPS trainees to vocational training; as previously training on knitting and RUB will negotiate that also their courses on tailoring, weaving and carpentry will be offered to BPS. The aim is to demonstrate that it is possible to design vocational training towards BPS and eventually to roll out the model to more VTCs in Rwanda. The link to these established institutions will cater to the lesson learnt that there is a need for increased technical assistance and links to qualify the member’s ventures into income generating activities. Participants for the VTC training will be drawn from MRCB graduates as well as selected RUB members (requirements include knowledge in reading and writing in braille and three years of primary education). After completion of training the participants will approach their local RIM branch to apply for start-up loans. The project will also provide small start up support in the form of knitting machines etc., and RUB will work to identify sponsors who can contribute to this. In contrast to the earlier related intervention, the project will establish a simple registry and follow the VTC trainees carefully, with a view to support and assess the viability and sustainability of the IGAs established. Inclusion in social protection/poverty alleviating programmes RUB will work on the access of its members to relevant government mainstream programmes (overview in Annex O) through branch trainings (refer Outcome 3) and through engagements with local authorities, facilitated by small scale advocacy and awareness raising funds (refer below). As outlined in chapter b.1., the local level authorities are the entry point as the decision making on distribution of social protection funds are made at this level. The increased focus on integration into mainstream programmes will happen in collaboration with the disability movement in general. NCPD, which has representatives at both sector and cell level, has included monitoring of government’s mainstreaming in its own strategic plan, and RUB will engage with both NCPD and NUDOR with a view to influencing local development plans so that these include PWD and specifically BPS issues. The local plans are based on performance contracts done at district level between sector and

19 There are no government centres providing training on agriculture in Rwanda, all are privatized.