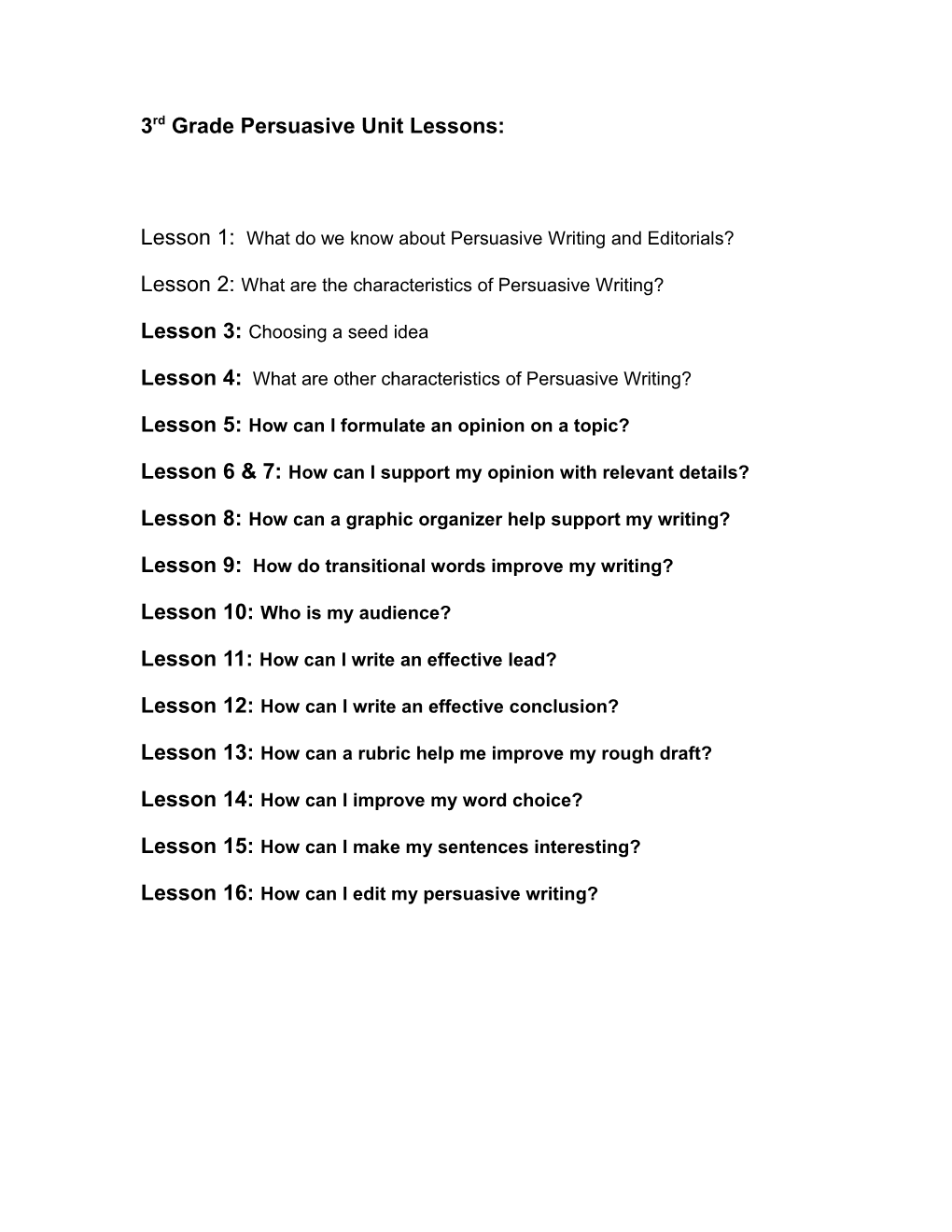

3rd Grade Persuasive Unit Lessons:

Lesson 1: What do we know about Persuasive Writing and Editorials?

Lesson 2: What are the characteristics of Persuasive Writing?

Lesson 3: Choosing a seed idea

Lesson 4: What are other characteristics of Persuasive Writing?

Lesson 5: How can I formulate an opinion on a topic?

Lesson 6 & 7: How can I support my opinion with relevant details?

Lesson 8: How can a graphic organizer help support my writing?

Lesson 9: How do transitional words improve my writing?

Lesson 10: Who is my audience?

Lesson 11: How can I write an effective lead?

Lesson 12: How can I write an effective conclusion?

Lesson 13: How can a rubric help me improve my rough draft?

Lesson 14: How can I improve my word choice?

Lesson 15: How can I make my sentences interesting?

Lesson 16: How can I edit my persuasive writing? Focus Lesson 1

Purpose: To determine what we know about persuasive writing and editorials

Materials:*A picture book that is a persuasive text ( i.e. “I Wanna Iguana”) and /or find articles from www.timeforkids.com, www.ajkids.com Scholastic news

*Student Writing Notebooks

Standards: ELA3W1a, ELA3W1b, ELA3W1m

Essential Question: What is persuasive writing?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson

“We’ve been talking about Narrative Writing and Informational writing. Another genre of writing that we’re going to explore today is persuasive writing.”

Modeling/Active Involvement:

Create (as a class) a brainstormed list of “What we notice about Persuasive Writing” after reading a persuasive article. This will become an anchor chart. The teacher will show students a sentence that states an opinion. For example, “Chocolate ice cream is better than vanilla ice cream.” Or “Burger King is better than McDonalds.” Ask students to turn and talk with a partner about their opinion of the statement.

Work Period: Students will work independently or with a partner to generate a list of topics that they have an opinion about in their writing notebooks.

Share Time: Select students to share some of the topics with the class. Focus Lesson 2:

Purpose To identify the characteristics of persuasive writing

Materials *Anchor Chart from previous day “What we notice about persuasive writing” *Student Writing Notebooks

Standards ELA 3W1a

Essential Question: What are characteristics of Persuasive Writing?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: Yesterday we heard a (persuasive mentor text or article) and then we developed an anchor chart that showed what we notice about persuasive writing. Today we are going to identify some characteristics of persuasive writing as well as practice developing a point of view.

Modeling/Active Involvement: Explain to students that they are going to participate in a “State Your Position” activity. Model this using the example “football or soccer.” Point to ½ of the room and say that this is where you would go if you liked soccer better and on the other ½ of the room, designate that area as where you would go if you liked football better. Have students stand up and begin by giving two choices and have them select one. Once they decide, have them move to the side of the room that is designated for that choice. Some examples of “choices” are: Georgia Bulldogs or Georgia Tech, chocolate ice cream or vanilla ice cream, Coke or Pepsi, summer or winter, beach or mountains, etc. Each time, give each group a white board and have them write down three reasons why they chose that choice. Explain the importance of choosing only one side. Tie this to generating a point of view and how in persuasive writing you have to have only one point of view on an issue. Tell students that this is just one of many characteristics of persuasive writing.

Work Period: Students may write on a persuasive writing topic of their choice. They may choose to write about one of the choices you gave them during the mini-lesson, but that isn’t required. Share Time: Students share what they wrote with a writing partner. Ask 2-4 students to share aloud with the entire group.

Focus Lesson 3:

Purpose: Choosing a Seed Idea

Materials: Table below (can be copied, pasted, and enlarged if need be)

Important Things to Consider When Choosing a Seed Idea Topic Important or Resource or Priority Interesting Support because… 1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Standards: ELA3W1m

Essential Question: How do I select a topic? What are my important reasons for selecting a topic to publish?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: Tell students there are many ways to choose a persuasive topic to write about. One of the easiest ways to brainstorm potential topics is to think of things you think are not fair.

Modeling/Active Involvement: Model beginning a list of things that you think are not fair (It’s not fair that I have to clean the whole house every Saturday. It’s not fair that teachers don’t get to order out for lunch. Etc.) Orally demonstrate how you can then write a persuasive piece about what’s not fair by trying to persuade others to agree to your side (i.e. Everyone should help clean the house on Saturday. Teachers should be allowed to order out lunch.) and that you’ll need to include some reasons in order to convince others to agree with you. Model using a topics list (in materials list above) and thinking aloud about why each idea is important enough (or not), which ideas you have resource information for (or not), and so on. Have the students suggest ideas they think are unfair for kids as you chart them. Then think through several of these unfair ideas and how they might look on the topics list (why each idea is important, where you might get resource information, etc.).

Work Period: Students may create their own unfair lists in their writer’s notebooks. Students may then write on a persuasive writing topic of their choice.

Share Time: Students share their writing with a writing partner. Ask 2-4 students to share aloud with the entire group.

Note: Many ideas from this lesson were taken from Denver Public Schools 5th Grade, Unit 6, Lesson 12.

Focus Lesson 4:

Purpose: To identify other characteristics of Persuasive Writing

Materials: *This chart (copy and paste onto an overhead).

What We Notice About Persuasive Writing

• States an opinion or position

• Gives reasons for opinions

• Backs up opinions with data, evidence, expert quotes, examples, and so on.

• Offers possible solutions

• Restates position in conclusion A persuasive writing model piece (either an article from a website in Lesson 1 or one of the books from the list on the Balanced Literacy Website Persuasive Writing page Student writing notebooks

Standards ELA 3W1a and ELA3W1l

Essential Questions: What are characteristics of Persuasive Writing?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: Have students recall what point of view is and how it relates to persuasive writing. Explain that today they are going to see a chart that identifies other characteristics of persuasive writing.

Modeling/Active Involvement: Show students the chart from above and have them identify words such as solution, opinion, and evidence, discuss their meanings and how they are all characteristics of persuasive writing. Then read aloud the sample persuasive writing piece and have students analyze how this piece had these characteristics of persuasive writing. It’s best if students can see the text as you read it, so you might print out copies for them to use or project the text for all to see. Ask students to be specific as they point out areas where the writer stated an opinion, gave reasons for their opinion, and backed up their opinion with facts, etc.

Work Period Students may then write in their writing notebooks. Challenge students to use the chart from today to make their persuasive writing better.

Share Time: Students share their writing with a writing partner. Ask 2-4 students to share aloud with the entire group.

Focus Lesson 5:

Purpose: To distinguish fact from opinion To formulate and defend an opinion about a topic

Materials: Persuasive Writing anchor chart (from yesterday’s lesson)

Standards: ELA 3R3d, ELA3R3q Essential Question: How is an opinion different from a fact? How do I form and defend an opinion about a topic?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: Explain to students that they are going to get to state their opinion, which is one of the characteristics that was mentioned in the chart from yesterday’s lesson. Express to students the importance of forming an opinion about a topic prior to writing about it.

Modeling/Active Involvement: Review fact and opinion by giving some examples of each and having students identify what each statement is. (This skill should have been taught during Reading Workshop but will be carried over during this lesson. This part should only last 2 or 3 minutes.) Next, explain to students that they are going to participate in an activity called “Fair or Unfair” which will allow them to state their opinion. For the fair or unfair activity, divide the room in half (just as you did for the “State Your Position” activity) and explain that one half is fair and the other is unfair. Then, give students different scenarios and have them move to the appropriate side of the room. Some examples of scenarios are: driving age 16, no hats at school, school uniforms, etc. Put students in pairs or small groups. Have them practice defending an opinion through role play. Have one student be the audience and the other student be the one who is trying to give his or her opinion about a topic and then defend it to the audience. Encourage students to give three reasons supporting their opinion.

Work Period: Students may then write in their writing notebooks. Students may choose to write on the topic they defended with their partner, or they may choose to continue a piece they began on another day or start a new persuasive writing piece.

Share Time: Students share their writing with a writing partner. Ask 2-4 students to share aloud with the entire group.

Note: Make sure the class is familiar with I Wanna Iguana before tomorrow’s lesson. Focus Lesson 6:

Purpose: Using supporting details and examples

Materials: I Wanna Iguana by Karen Kaufman Orloff

Standards: ELA3W1i

Essential Question: How can I support my position with relevant details and supporting examples and/or reasons?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: Yesterday we learned how to form an opinion about a topic. Today we are going to learn how to support our opinion by adding details and examples to our persuasive writing.

Modeling/Active Involvement: The class should be familiar with the book I Wanna Iguana. The class will discuss what this writer did well. As a group pick out some general information and specific details. Have students call out and categorize them as either general information or specific details. Teacher will then model a general information sentence and then add some details to make it a specific details sentence. For example, “Schools should not require students to wear uniforms” is a general information sentence. “School uniforms can be too expensive for some families to buy” would be a specific sentence with details. Ask students look through their persuasive writing so far and identify an area in their writing where they wrote a general sentence and then add specific detail sentences. Have 2-3 students share their general sentence and their ideas for adding details.

Work Period: Students may write in their writing notebooks.

Share Time: Students share their writing with a writing partner. Ask 2-4 students to share aloud with the entire group. Select students to share their general sentences and how they added more specific details. Focus Lesson 7:

Purpose: Using supporting details and examples (continuation of Focus Lesson 6)

Materials: I Wanna Iguana by Karen Kaufman Orloff Chart paper Optional:

Standards: ELA3W1i

Essential Question: How can I support my position with relevant details and supporting examples and/or reasons?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: Yesterday we learned about general vs. specific sentences. Today we are going to learn how to add supporting details and examples to our persuasive writing.

Modeling/Active Involvement: Review with the class from Focus Lesson 9 about general sentences vs. specific detail sentences. Write a sample opinion on a topic on chart paper, then as a class brainstorm 3 adequate reasons for your opinion. Have a discussion about how the reasons need to be valid and the author can’t say “because it’s good”. (See end of lesson for details)

Work Period: Have students work independently on their persuasive piece. As you confer, check for specific reasons for their opinions in their writing.

Share Time: Select students who have a good understanding of today’s mini- lesson to share their writing. Sample Topic: People should stop cutting down trees

3 poor reasons (These would be the ones that would not be valid. This is an example of what the students should not do.)

1. I love trees. 2. Trees are pretty. 3. I like to climb the trees in my back yard.

3 valid reasons (These are examples of reasons that we want the students to do.)

1. Many animals are losing their homes because people are cutting down trees to build more buildings and homes. 2. Trees provide oxygen to all living things. 3. If there are no trees the land will continue to wash away.

Focus Lesson 8: Purpose: To use a graphic organizer to organize information for persuasive writing.

Materials: Student copies of persuasive graphic organizer (See several options on county Balanced Literacy website Persuasive Writing page: “flowchart” or “Persuasive Writing Graphic Organizer”) Transparency of persuasive graphic organizer

Standards: ELA3W1b,l,m

Essential Question: How can I use a graphic organizer to support the organization of a persuasive writing draft?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: Yesterday we learned that we need supporting details and examples in our writing to convince the reader to agree with us. Today I am going to show you a specific graphic organizer that will help you organize these details and examples in your writing.

Modeling/Active Involvement: Review what the purpose of a graphic organizer is. Then on the overhead projector display the graphic organizer. Ask the kids “What do you notice about this graphic organizer? How is it different from other graphic organizers we have used in the past?” Review with the class “What are the characteristics of good persuasive writing?” Display the transparency of the graphic organizer and go over all of the parts in detail. Using the demonstration topic from yesterday, have students help you complete the graphic organizer.

Work Period: Give students copies of the graphic organizer. Have them complete the graphic organizer on the topic they’re currently writing about, and then compare the graphic organizer to their writing and see if their writing is organized and make adjustments as needed. Share Time: Have students share with their writing partner their graphic organizers and how it compared to their writing as well as any adjustments they made.

Note: If students need more time organizing their writing using this graphic organizer, spend more than one day on it. Determine students’ needs based on individual conferences and then use the following day’s mini-lesson to address any confusions you see that students have.

Focus Lesson 9:

Purpose: How to use transitional words and phrases in your writing

Materials: Student copies of Young Author’s List of Transitions (“Razzle Dazzle Writing” p. 38) – see end of lesson Transparency of “Clean Earth” Standards: ELA3W1 e

Essential Question: How can I make a smooth transition from one idea to another?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: Yesterday we used a graphic organizer to help organize our writing. Today I am going to teach you to use good transitions so that your writing will not sound choppy.

Modeling/Active Involvement: Discuss with the kids the word transition. This will let you know if they know what the word transition means. A transition is like a bridge between two different ideas or two different kinds of writing. Hand out the student copies of Young Author’s List of Transitions and read over a few of them. Then display the transparency “Clean Earth” (version 1).Discuss what they notice about the piece of writing: good lead, uses details, but jumps from one idea to another. Ask the class “What would happen if we added a transition paragraph?” As a class use the list of transitional words and phrases and write a transition paragraph. Lastly look at “Clean Earth” (version 2) to see how the author wrote their transition paragraph. Discuss how it made a difference in his/her writing.

Work Period: Have students work independently on their persuasive piece. As you confer, check for specific areas that need transitions in their writing.

Share Time: Select students who did a great job on adding transitions to their writing.

Note: The chart “Young Author’s List of Transitions” comes from Razzle Dazzle Writing: Achieving Excellence Through 50 Target Skills by Melissa Forney Clean Earth Version 1:

You are walking in your favorite park. Flowers are everywhere and birds are singing. People are playing in the sparkling, clear creek. The sky is blue and the air is clean. It is a beautiful day!

The laws in Greenville allow people to throw trash on the ground and not get punished. Even though there are signs posted that warn people not to throw down trash, if they do, nothing happens to them. I think Greenville should pass laws that make it illegal to trash up our city. We should have police officers walking around to watch to see if people follow these laws. If we had laws against polluting, then more people would want to get outside to play, and if more people played outside then they’d be healthier and not so fat. The clean air would be good for people’s lungs, unlike the polluted air in Greenville right now. If the parks and streets were cleaner it would be safer for animals. Many times animals eat trash and get sick or even die. Sometimes birds get plastic bottles or other trash stuck on their heads and then they starve to death. If we had laws against littering then fewer animals would be hurt. If there were laws against polluting then more people would want to come visit Greenville. If more visitors came here then the shops and restaurants would sell more things and we could make more money for our citizens. I think Greenville should pass laws outlawing polluting. By having a cleaner city we could be healthier, our animals would be safer, and we could make more money for our town.

Version 2:

You are walking in your favorite park. Flowers are everywhere and birds are singing. People are playing in the sparkling, clear creek. The sky is blue and the air is clean. It is a beautiful day! Everyone enjoys walking outside on a beautiful day. Unfortunately, our town, Greenville, does not look like this! If you were to walk through Greenville, chances are you’d see trash everywhere, dirty creek water, and polluted clouds in the air. The laws in Greenville allow people to throw trash on the ground and not get punished. Even though there are signs posted that warn people not to throw down trash, if they do, nothing happens to them. I think Greenville should pass laws that make it illegal to trash up our city. We should have police officers walking around to watch to see if people follow these laws. If we had laws against polluting, then more people would want to get outside to play, and if more people played outside then they’d be healthier and not so fat. The clean air would be good for people’s lungs, unlike the polluted air in Greenville right now. Also, if the parks and streets were cleaner it would be safer for animals. Many times animals eat trash and get sick or even die. Sometimes birds get plastic bottles or other trash stuck on their heads and then they starve to death. If we had laws against littering then fewer animals would be hurt. Finally, if there were laws against polluting then more people would want to come visit Greenville. If more visitors came here then the shops and restaurants would sell more things and we could make more money for our citizens. In conclusion, I think Greenville should pass laws outlawing polluting. By having a cleaner city we could be healthier, our animals would be safer, and we could make more money for our town.

Focus Lesson 10:

Purpose: Identifying the Audience

Materials: *Blank piece of chart paper *Student writing notebooks

Standards: ELA3W1a, ELA 3W1m, ELA3W1l

Essential Question: How do I determine who my audience is? Why is it important to identify my audience when writing a persuasive story?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson:

Ask students if they have ever had something read to them that they didn’t understand (maybe in a nonfiction book, science book, newspaper article, etc.) Ask them how that made them feel. Share a time when you were confused after reading something that someone had written (maybe it was “over your head” or an unfamiliar topic). Tell students that the reason for asking these questions and sharing your experience is that it is important for writers to think about who their audience is before they begin to write. You may want to continue by saying that you wouldn’t use big words with kindergartners just like you wouldn’t use really easy words or phrases with most grown-ups. Explain that today they are going to have some time to think about who their audience will be for their persuasive piece.

Modeling/Active Involvement: On the blank chart paper, write audience across the top. Have students help you brainstorm some difference audiences. Once the chart is made, model looking at the list and circling who your audience is for your writing topic. Continue by stating some of the things that you will be sure and do now that you have decided who your audience is. Have students turn and talk to their partner to share who they think their audience is. You may decide as a class on an audience for your publishing celebration at the end of this unit. For instance, you might choose to invite the parents in to hear your finished persuasive pieces. Or you might choose to invite a class of younger students in as an audience. Once students have an audience in mind, they will often write more carefully and be more willing to revise, knowing that others will read their finished product. Have students orally discuss while you chart some of the things that they will need to do to help persuade their audience. (Ex. Use better/more simple word choice, relate the topic to them by making it personal, be very knowledgeable-give facts, give clear examples, etc.)

Work Period: Have students work independently on their persuasive piece.

Share: Have students share their writing with their writing partner. Ask 2-4 students to share with the entire group.

Note

Many ideas from this lesson were taken from Denver Public Schools 5th Grade, Unit 6, Lesson 13.

Focus Lesson 11:

Purpose: To write effective leads

Materials: Mentor texts (picture books for persuasive) and previously read persuasive articles

Standards: ELA3W1a

Essential Question: How can I write effective leads to capture the reader’s interest and set a purpose for my writing?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: We’ve been studying how to make our persuasive writing better by using transition words and choosing our audience. Today we are going to learn how to write a strong lead sentence for our persuasive writing. Modeling/Active Involvement: The class should be familiar with different types of lead sentences from previous mini-lessons the teacher has taught in other writing genres. The teacher will project the chart of mentor texts and the type of lead used in the text from the examples of types of leads at the end of this lesson. The class will discuss why the author chose that type of lead sentence. The teacher will take his/her persuasive topic and model the different types of lead sentences and decide which fits best (see “Try 6” at end of lesson). Have students turn and talk with their partner to vote for the best lead sentence and why.

Work Period: Students can either independently or with a partner do the “Try 6” activity with the persuasive writing piece they’re currently working on. After choosing the best lead, students will work independently to add their lead sentence for their introductory paragraph and continue writing after they’ve worked on their lead sentence.

Share Time: Select students to share their lead sentence and why they chose that particular one.

Note This is a sample of leads that may be used throughout the year when introducing different types of lead sentences.

Samples of Strong Leads and Their Strategies Imagine: Author engages readers by bringing them right into setting. Example: “The pioneers who cross the Appalachian Mountains depended on trees and forests for food and shelter. Imagine starting over in a place with almost no tress. Add to that, blizzards in the winter and swarms of grasshoppers in the summer. For some pioneers, the hardest part of life was getting to their new home. But for the settlers of the Great Plains, known as sodbusters, getting there was easy compared to what came next.” “Sodbusters,” Kids Discover, August 1999 Student written example: “Imagine you are in a long hallway. You can’t see the beginning or the end. The hallway is miles long. You look up. Someone has put a pattern of bathtubs and mirrors upside on the ceiling. As far as you can see, there are bathtubs and mirrors.”

Question: Author starts with an important question that makes readers think or wonder about the answer. Example: “Do you ever wonder when you look at buildings in your own town or city, as well as those in other parts of the United States and in other countries, about the amount of work involved in their construction?” “View From the Crow’s Nest : American Architecture,” Cobblestone, August 1988

Student written example: “Have you ever wondered how you talk to your best friend or a family member just by picking up something called a phone and dialing seven numbers?” Student written example: “Have you ever heard of the composer that was deaf?”

Right to the Point: Simple, short sentence that tells the readers what the report is about, but does not say “This report is about….” Example: “Spiders live in many places. They live at the top of mountains or on the bottom of caves. Some live in damp areas. Others live in deserts. Some spiders live on the ground, some in trees and some in buildings.” A Look at Spiders, 1998 Student written example: “Many parts make up a computer. The video card translates instructions into a computer. An expansion card lets you add new features to a computer. The computer also holds a sound card that determines the sound quality produced.”

Hanging On: Author gives readers some clues and readers try to guess what is being described. Example: “Its body stretched flat in the water, the hunter swims toward the prey. One hop and the hunter is out of the water, snatching its catch. Lickings its lips, it prepares to devour its meal. A ruthless killer? An unlucky victim? Nope. The hunter is a fluffy muskrat, looking more like a bedroom slipper than a dangerous predator. Its prey is an apple slice, hidden in an exhibit at the Museum of Life and Science in Durham, NC.” “Call of the Wild,” Boys’ Life, July 1999

Student written example: “Try to imagine that you are on a trip in South America. You are on a tour of a Brazilian rain forest, and you see a spotted animal and a black animal. You think the spotted animal is a jaguar, but you’re not sure. Can you guess what kind of animal the black one is? Well, as you might have guessed, the black animal is not a black panther. But it is a female jaguar. Female jaguars are usually always black. In fact, a jaguar cub usually will have a black mother and a spotted father.”

Adapted from Integrating Research Projects with Focused Writing by Mary McMackin and Barbara Siegel, an article online from the Reading Online Web site, www.readingonline.org/articles/mcmackin/index.html#leads1

Other Types of leads include:

Dialogue Lead: “Where’s Papa going with that axe?' said Fern to her mother as they were setting the table for breakfast. ~ Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

Sound Lead: “Zoom! Zoom! Zoom! I’m off to the moon! ~ Zoom! Zoom! Zoom! I’m off to the moon! by Dan Yaccarino

Setting Lead: Rancher Hicks lived out West. As far as the eye could see there was nothing…not even a roaming buffalo. So nothing much ever happened. ~ Meanwhile Back at the Ranch by Trinka Hakes Noble

Try 6 Types of Leads Examples from mentor texts Imagine lead sentence Setting lead sentence Dialogue lead sentence Question lead sentence Sound lead sentence Hanging on lead sentence

Focus Lesson 12:

Purpose: Writing Effective Conclusions

Materials: Previously used editorials or mentor texts for persuasive writing Chart paper Writer’s notebooks

Standards: ELA3W1g

Essential Question: How can I use mentor texts to craft effective conclusions?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson: Yesterday we worked on making the leads to our persuasive writing interesting and inviting. Today I am going to teach you how to write a conclusion using mentor texts.

Modeling/Active Involvement: Using previously read mentor texts and editorials, examine and review different types of conclusions. You may want to make an anchor chart (this can be made ahead of time) to display the different types for persuasive writing (see end of lesson). The students can copy this ahead of time in their writer’s notebook. After reviewing the types of conclusions, examine the mentor texts for the best conclusions. Think Aloud to the class “What makes this conclusion interesting, effective, or memorable?” The students can turn and talk with their partner. Also during this time ask students these questions: “What seems to be the purpose of conclusions in the mentor texts?” “What did each author do to make the conclusion memorable?” “Which ones might work well for your editorials?” Model for the students 3 different ways you would conclude your persuasive writing referring back to the anchor chart. “Today during our independent writing time you and your partner will try 3 different types of conclusions for your persuasive piece. You will decide which one is the best choice.”

Work Period: Have students work with their partner and write 3 different conclusions based on the anchor chart the students copied down in their writer’s notebook. Students can also continue writing independently.

Share Time: Select students to share their 3 different conclusions and ask which one they chose and why.

Note

Anchor chart for conclusions

Types of Conclusions for Persuasive Writing Restate your lead sentence

Call to action

Create a positive or memorable image

Summarize and connect to central message

Clever or thought provoking comment

Focus Lesson 13:

Purpose To use the state rubric for persuasive writing to help students revise their rough drafts

Materials Persuasive Writing state rubric, including individual copies of the rubric for each student Overhead of teacher’s rough draft Blank overhead to write revision ideas Students’ rough drafts

Standards ELA3W1 e,i,l,m ELA3W2 d,f,h

Essential Question: How do I use the persuasive writing rubric to improve my rough draft? Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson “Over the past couple of weeks you’ve been working on many different persuasive writing pieces. Now it’s time to choose one piece to publish. We are going to take a closer look at our rough drafts and see what areas we can revise to make them even better. The rubric will help us reflect on how well we did on the writing so far and what we might be able to improve upon.”

Modeling/Active Involvement Display the overhead of your own rough draft and read it aloud once. Model looking the rubric category for “ideas” and “organization”. Tell how you would score yourself and why. (Leave some room for improvement). Think aloud about how the rubric shows you what you can do to strengthen parts of your draft. On your persuasive writing, make revisions in the margins or use large sticky notes in places that need more significant change or elaboration. Ask the students to talk to their partner about how they think you did regarding the “style” section of the rubric. As they make suggestions for changes you can make, record these on the margins or on sticky notes. Explicitly show them how you might add larger sections of text using sticky notes. (This part of revision is very difficult for some students – if they don’t see an “easy” way to add text, they will simply choose not to. It’s important for us to provide them with solutions that make revision an easier process). Repeat this with the “conventions” section of the rubric.

Work Period Ask students to work with partners and look at one rubric category you specify and have them reread parts of their editorial drafts. Students talk with their partners about how they would score themselves and how they could improve their writing in that rubric category. Some questions to consider: 1) Does your lead grab your writer’s attention? 2) Does your draft offer evidence to support your position? 3) Did you use transition sentences to make your position clearer and more convincing? 4) Did you restate your ideas in your conclusion (in a different way than before)? 5) Does your conclusion wrap it up or does it leave more questions? Tell students to revise their drafts using the rubric and suggestions discussed. Remind them to make corrections and suggestions in the margins or with sticky notes. The teacher should use this time to confer with students about their writing or bring small groups of students together who need more support or specific instruction. Some students may need more time to choose the piece they will publish and may not be ready to begin revision. There needs to be flexibility to allow students to complete the assignment at their own pace. Everyone will not be at the same point in their own writing.

Share Time Students can share with their “Turn and Talk” partners about one area they chose to revise. Select a few students to share out to the whole group.

Focus Lesson 14:

Purpose To choose words that are not too general so that your exact meaning becomes clear in your writing. This includes persuasive vocabulary and transitional words.

Materials Teacher’s rough draft on chart paper or overhead transparency Previously-made anchor charts on persuasive vocabulary and transition words Student drafts State rubric for persuasive writing Optional: “Craft Lessons” (Ralph Fletcher) p. 59 Cracking Open General Words

Standards ELA3W1 e,f,h,m ELA3W2 h

Essential Question: How do I improve the word choice in my persuasive writing to include words that are not too general? How can I use good persuasive and transitional vocabulary?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson “We’ve been busy creating our persuasive writing over the past couple of weeks. We’ve begun the revision process by looking at the state writing rubric and marking areas that we may need to change. Today we’ll be looking specifically at the word choices that we’ve made to determine if they say exactly what we want them to say. We’ll also make sure we’ve included persuasive vocabulary and clear transitional words.” Modeling/Active Involvement The teacher chooses a paragraph from her rough draft and rereads it aloud. She models thinking about how she could change just a few words and make it much better. She should explain her thinking and model taking a couple of persuasive vocabulary words and substituting them in for other less expressive words. She should also model placing a transitional word in the paragraph to make the story flow better. This should all be done in front of students, with her thinking shared. OR Rather than use her own writing, she can choose a student’s writing and share how she would revise a paragraph of this piece. Sometimes this is useful, especially for a student who needs additional support, but make sure that the student is secure enough to have his/her writing used as an example.

Students should get their writings and turn to their partners. The teacher will ask them to choose a word from their own writing that they believe should be changed. They might be encouraged to choose from the persuasive vocabulary list or perhaps a transitional word.

Work Period Students will go off to work on the revision process. It will most likely take more than one day for students to make revisions in their writings. Students should work at their own pace with some finishing before others. The teacher should use this time to confer with individual students or pull small groups that need to work on the same things.

Share Time Choose a few students to share how they changed a word or words to make their writing better. Have students read the “before” and “after” so the audience will understand how the writing is now better.

Focus Lesson 15:

Purpose To vary sentence structure within the persuasive writing

Materials Teacher’s rough draft (either on chart paper or overhead transparency) Anchor chart on varying sentence structure (if one has been created previously) Optional: “Razzle Dazzle Writing” (Melissa Forney) p. 132 – Sentence Variety Standards ELA3W2 i ELA3C1 e,f,g

Essential Question: How do I make sure that my sentences are constructed in different ways that will give my writing interest and rhythm?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson “As we’ve been working on our persuasive writings, we’ve learned different ways to make sure our writing is the best it can be. We’ve looked at our details to make sure they are convincing. We’ve looked at our word choice to make sure we’ve chosen words that exactly express our meanings. Today we’re going to look at our sentence structure and make sure that all of our sentences are not beginning the same. We need to make sure our writing isn’t choppy or monotonous.”

Modeling/Active Involvement The teacher writes an example sentence on chart paper: “Hershey Kisses are the best candy.” Then she writes underneath: “Sweet, creamy Hershey Kisses are the best candy.” Discuss how the second sentence is structured differently with adjectives first. This is only one way that a sentence can be changed. Have students look at their own rough draft and choose a sentence that they believe they can change to perhaps include an adjective or two at the beginning. This is an easy way to vary sentence structure. Depending on your class, you can model changing another sentence – but this time maybe choose two short sentences and combine them to make a compound sentence. Whatever is modeled, the students will need to practice the strategy in their own writings.

Work Period Students continue to work on revising their rough drafts. They are encouraged to look specifically at sentence structure today to improve the quality of their writing. Teacher continues to conference or work with small groups.

Share Time Select students to share how they improved their sentence structure. They can read the “before” and “after” with students contributing ideas of how the sentence was changed. Teacher can ask, “What did he do to make the sentence better?” Focus Lesson 16:

Purpose To edit our persuasive writing essays

Materials Teacher’s rough draft Pens to mark areas for editing State writing rubric (conventions) Students’ writing drafts and copies of the rubric for each student Benchmark writing samples (from DOE)

Standards ELA3W1 m ELA3W2 i ELA3C1 e,k,l,m

Essential Question: How do I edit my writing so that it is easily read and understood?

Connecting to Background Knowledge/Previous Lesson “We’ve been hard at work completing our persuasive writings. We’ve written our rough drafts, and over the past days we’ve looked at ways to revise our writings to make them even better. Now it’s time to take a closer look at our conventions to make sure we have correct punctuation, capitalization, and have made our best efforts at spelling.”

Modeling/Active Involvement The teacher will model going through a paragraph of her own rough draft to look for conventions that are mentioned in the state rubric. The teacher will focus on capitalization, punctuation, and spelling. The teacher will find areas of her own writing that needs to be corrected. OR She can choose another paragraph (perhaps from a student in the classroom) or a benchmark paper that has several types of errors that she can help correct with student input. As she goes through these errors, she makes sure she is pointing out the rubric and how these errors will impact the student’s score and writing quality. She should model writing the corrections on the rough draft. She can circle words that she needs to look up in the dictionary to check the spelling. Students will need to practice their editing before going off on their own. The teacher could write a few sample sentences on a chart and have students get with their “Turn and Talk” partners to see if they can fix-up the writing using the editing lesson from the teacher. They will then have a minute to discuss how they “fixed-up” the writing.

Work Period Students will work to edit their own rough drafts.

Share Time The sharing would probably take place before sending students off to edit their own work. The sharing could be from the few sentences the teacher put on the chart before the work period.

Note At this point in the unit, all mini-lessons have taken place and students are working to finish revisions and editing. Because this is an individual process, some students will finish this process today, while others will need another day or two.

Because this is the end of the persuasive writing unit, students will need to complete a published work. This means that they will need to re-write or type their persuasive writing so that it will be ready for turning in and grading (using the rubric). The teacher will most likely need to devote the next day or two to completing this process. The teacher should choose a day that students will have their published works completed by so that the “Publishing Celebration” can occur.

Standards for revision and editing days: ELA3W1 n, ELA3W2 i, ELA3C1 j ELA3SV1 c,d