Assessing union density and bargaining coverage in Portugal

October 2015

Union density Measuring union membership in Portugal is fraught with problems. The figures that unions themselves publish are exaggerated, due to competition for influence, and they cannot easily be verified. These figures also include many members who have retired from the labour market. There have been careful studies of union records that, although not complete, allow to track the development over time of union membership and density in Portugal, as is done in the ICTWSS database, which is also the source for the OECD time series. The estimated 18-20 percent density rate of recent times is confirmed in the Government White Paper of 2009. Note that this rate includes the public sector where density is believed to be much higher.

Would it be better to use the data contained in the Relatório Único available for 2010-2012? I think not, for two reasons. The source of the data are managers responding to a survey question: “Indicate the number of workers for whom you have knowledge of their membership in a union (because they are union officials, because you deduct membership dues from their salary, or because the worker informed you about his/her membership so as to determine which particular collective regulation is applicable to their case).” I understand that answering this question is obligatory which means that there is no issue of 'non response'. But do managers really know? And do union members whose dues are not 'checked off' really want them to know? In Portugal with its highly divisive model of unionism and conflicting labour relations, this is not very plausible. Should we interpret the resulting density rates, calculated from this survey, as anything more that the 'check off' rate of union membership - a sort of minimum 'baseline'?

This would not be a major criticism if employer deduction of membership dues was universal in Portugal (as it once was under Salazar), but it isn't. Research by Naumann based on interviews with officials from six different unions has revealed that between 8 and 72 percent of the members pay directly to their union. Unsurprisingly there is a direct correlation between the union density rate (by sector or firm size) and the check off rate (peaking in banking, insurance, utilities and larger firms), which turns this in a nice artifact.

The second reason why I find the Relatório Único data of limited use is that the survey (which was actually sent to the ILO, for validation, a project in which the author was involved) includes only private sector workers under the Code du Travail (which does not include all workers under temporary and agency contracts, is limited in its coverage of agriculture and household work, and excludes the public sector; for the same reason it is not such a great source for calculating coverage rates, see below). Trade unions in Portugal, as everywhere else in Europe or North America, include a high and (until recently) increasing membership share of public sector workers. In short, the Relatório Único data do not allow any conclusion regarding the aggregate rate of unionization in Portugal. The best one can conclude from the data is that, among full time workers in the private sector with employment contracts defined under the Code du Travail and with union membership contributions paid through their employer, union density did not change much between 2010 and 2012 and remained in the order of 10 percent. This need not conflict with a 'true' aggregate density rate of 18 percent.

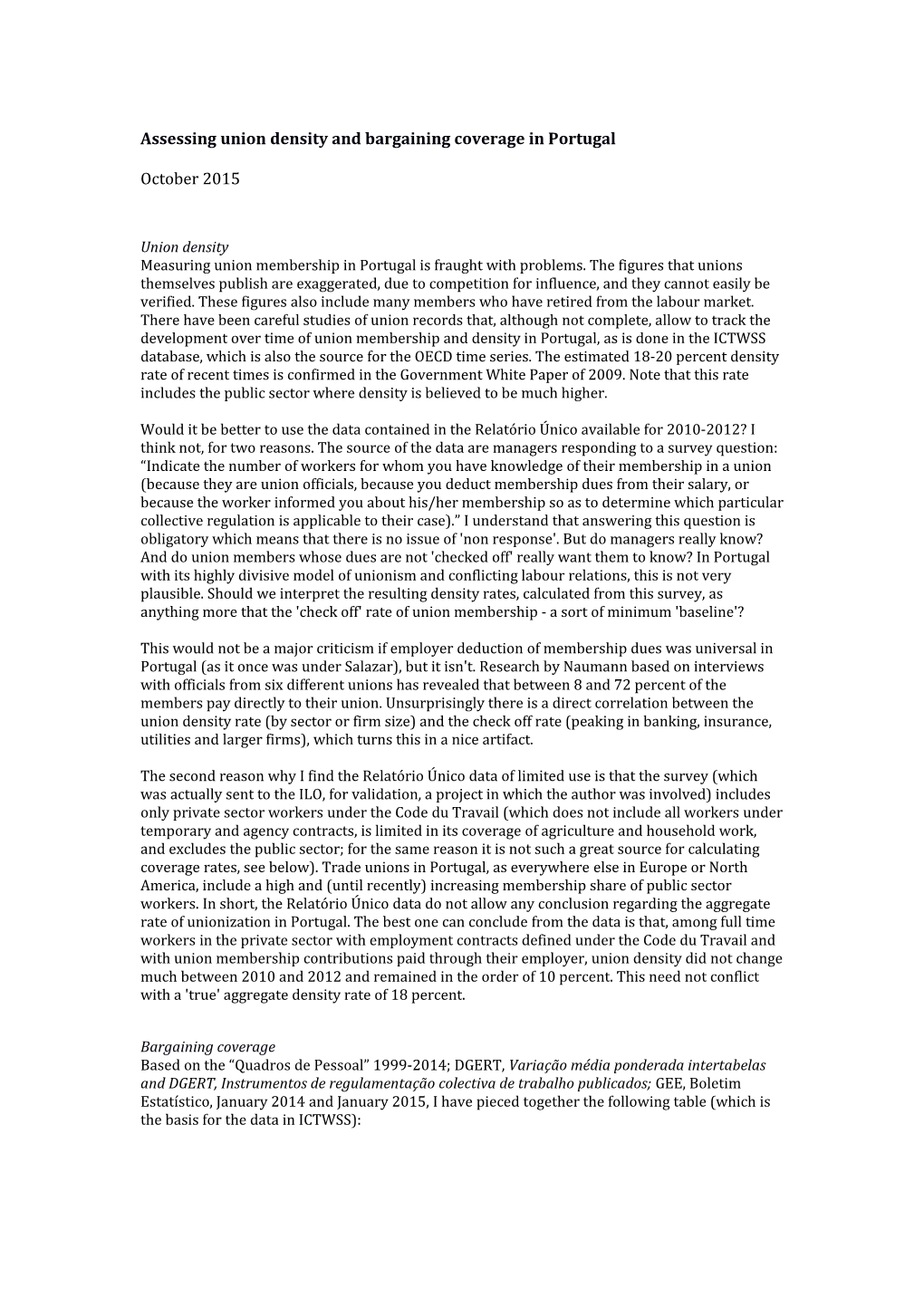

Bargaining coverage Based on the “Quadros de Pessoal” 1999-2014; DGERT, Variação média ponderada intertabelas and DGERT, Instrumentos de regulamentação colectiva de trabalho publicados; GEE, Boletim Estatístico, January 2014 and January 2015, I have pieced together the following table (which is the basis for the data in ICTWSS): employe employees rati coverag coverag coverage employees es employe covered by o LFS e rate e rate rate old covered by (private es Yea CLAs flow data, new old and new all existing sector, (under r published : Eurosta CLAs CLAs CLAs CLAs under pulic in given stoc t, OECD (adjuste (adjuste (adjuste (stock) Labour statute) year (flow) k d) d) d) Code) 199 0.7 1,465.0 1,953.0 2,288.0 716.0 3,516.2 52.3 17.4 69.7 9 5 200 0.6 1,453.0 2,295.0 2,371.0 720.0 3,617.1 50.2 29.1 79.2 0 3 200 0.6 1,396.0 2,200.0 2,416.0 725.0 3,675.6 47.3 27.2 74.6 1 3 200 0.6 1,386.0 2,183.0 2,460.0 730.0 3,718.3 46.4 26.7 73.1 2 3 200 0.6 1,512.0 2,379.0 2,510.0 735.0 3,701.8 51.0 29.2 80.2 3 4 200 0.2 600.0 2,390.0 2,574.0 740.0 3,746.5 20.0 59.5 79.5 4 5 200 0.4 1,125.0 2,491.0 2,739.0 748.0 3,785.3 37.0 45.0 82.0 5 5 200 0.5 1,454.3 2,483.0 2,766.0 727.0 3,868.3 46.3 32.7 79.0 6 9 200 0.5 1,570.0 2,682.0 2,970.0 709.0 3,867.2 49.7 35.2 84.9 7 9 200 0.6 1,704.0 2,731.0 3,018.0 692.0 3,918.6 52.8 31.8 84.6 8 2 200 0.5 1,303.0 2,605.0 2,879.0 675.0 3,826.4 41.3 41.3 82.7 9 0 201 0.5 1,407.1 2,392.0 2,709.0 645.0 3,819.5 44.3 31.0 75.4 0 9 201 0.5 1,237.0 2,334.0 2,660.0 630.0 3,783.5 39.2 34.8 74.0 1 3 201 0.1 328.0 2,142.0 2,486.0 610.0 3,596.9 11.0 60.7 71.7 2 5 201 0.0 187.0 2,125.0 2,434.0 570.0 3,514.4 6.4 65.8 72.2 3 9

What this table shows is, firstly, that the aggregate bargaining coverage rate, after adjustment for the fact that wages and terms of employment in the public sector are not set by collective agreement, is lower than the 90 percent that is usually cited for Portugal (but based on a very restricted legal definition of employment). Secondly, even if old and new agreements are given equal weight, the coverage rate has fallen with some 12 percentage points since the outset of the crisis (from 84.8 to 72.2 percent). (My initial estimate for 2013 was 67 percent, based on an earlier publication of the Ministry showing 1.95 million workers covered by all, new and old, agreements in force in 2013; this has been updated to 2.1 million since).

The key question is whether we should give old and new agreements the same weight? Naumann (2015), after a careful examination of the agreements, estimates that at least half of them are now more than eight years old and uses wage tables from before the recession. Accumulated cost inflation since 2008 is above 10 percent (OECD.stat). It is plausible that an increasing proportion of the covered workers find protection through the statutory minimum wage rather than through collective bargaining (this issue is not new in Portugal and it is also not limited to Portugal - see my observations on France). Naumann estimates that no more than 1.5 million out of the 2.1 million employees covered by collective agreements in 2013 had their contracts renewed since 2009. That would bring the coverage rate down to 51 percent. The problem with that estimate is that we have no way to make similar corrections for earlier years (and for other countries, especially France). That is why I have not gone than that road and treated the stock of agreements as if these agreements had the same value as new agreements, knowing that this is not the case and that the absence of renewals is a sign of deep crisis even in times of almost deflation.

Naumann, R. (2015), Study of the extension and general application of collective bargaining in Portugal. Unpublished paper prepared for the ILO, project on the use and application of extension in collective bargaining, directed by S. Hater and J. Visser, final version, September.