Bundist Countercultue Lithuania, to the Bishopric of Wilno (Now Vilnius) Triggered an Ongoing Row

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protegowani Jakuba Bermana Jako Przykład Klientelizmu I Nepotyzmu W Elicie Władzy PRL

VARIAIII MIROSŁAW SZUMIŁO Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie Biuro Badań Historycznych Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej Protegowani Jakuba Bermana jako przykład klientelizmu i nepotyzmu w elicie władzy PRL Zjawisko klientelizmu w perspektywie historycznej było już przedmiotem wielu prac naukowych. W Polsce zajmował się nim przede wszystkim Antoni Mączak1. Wzbudzało ono również zainteresowanie zachodnich sowietologów, którzy zauważyli, że niemal od początku rządów bolszewickich w Związku Sowieckim następowało grupowanie kadr wokół wpływowych towarzyszy2. Analizie poddawano m.in. układy klientelistyczne w ekipie Leonida Breżniewa3. Według Johna Willertona klientelizm oznacza wzajemne popieranie własnych interesów w zakresie uczestnictwa w elicie władzy, interesów frak- cyjnych i sektorowych oraz wspieranie się w trakcie kariery w związku ze wspólnym pochodzeniem etnicznym, pokoleniowym itp.4 Tworzenie się sieci klientelistycznych oraz nepotyzm w elicie władzy PRL nie były do tej pory przedmiotem odrębnych badań. W ujęciu socjologicznym poru- szał to zagadnienie Krzysztof Dąbek, ale tylko w kontekście funkcjonowania ukła- dów patron–klient w aparacie partyjnym w latach 1956–19805. W odniesieniu do kadry kierowniczej Służby Bezpieczeństwa tego typu dysfunkcje analizował Daniel 1 A. Mączak, Nierówna przyjaźń. Układy klientalne w perspektywie historycznej, Wrocław 2003. 2 T.H. Rigby, Early Provincial Cliques and the Rise of Stalin, „Soviet Studies” 1981, nr 33, s. 25. 3 J.P. Willerton, Clientelism in the Soviet Union: An Initial Examination, „Studies in Comparative Commu- nism” 1979, nr 12, s. 159–211. 4 Ibidem, s. 162. 5 K. Dąbek, PZPR. Retrospektywny portret własny, Warszawa 2006, s. 201–216. 456 2 (34) 2019 pamięć i sprawiedliwość Protegowani Jakuba Bermana jako przykład klientelizmu i nepotyzmu w elicie władzy PRL Wicenty6. -

Download File

Kawaleryjskie barwy i tradycje współczesnych jednostek wojskowych… #0# DOI: 10.18276/pz.2020.4-02 PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNIOPOMORSKI ROCZNIK XXXV (LXIV) ROK 2020 ZESZYT 4 ARTYKUŁY Katarzyna Rembacka ORCID: 0000-0002-4009-3390 Instytut Pamięci Narodowej e-mail: [email protected] Collective or individual biography? A communist in “Regained Lands” just after the WW2 Key words: Western and Northern Lands in Poland, Polish Government Plenipotentiaries, communists, biography, 1945, human resources policy Słowa kluczowe: Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne w Polsce, Pełnomocnicy Rządu RP, ko- muniści, biografistyka, 1945 rok, polityka kadrowa It would be appropriate to begin by explaining the research perspective outlined in the title. The key to the analysed problem, i.e. the biographies of people taking over and being in power after the end of the Second World War on the Western and Northern Territories, were ideological choices made by them. They deter- mined their fate, and it is through their prism that we can look at the history of regions which, as a result of the post-war transformation of Europe, found them- selves within the borders of Poland. It should be noted, however, that the subject under consideration is only a research “sample” as it is limited to a relatively small collection. It is made up of biographies of people who, in March 1945, were appointed government plenipotentiaries of new administrative districts.1 Of this group, special attention will be paid to one of them – Leonard Borkowicz (until 1944 Berkowicz). It is his personalised history that will allow us to analyse the 1 Archive of New Files (hereinafter: AAN), Ministry of Public Administration, Excerpt from the minutes of the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 14 March 1945, ref. -

Dowód Na Polski Antysemityzm Czy Raczej Świadectwo Przełomowych Czasów? (Przyczynek Do Stosunków Polsko-Żydowskich)

Dzieje Najnowsze, Rocznik LI – 2019, 4 PL ISSN 0419–8824 Jacek Piotrowski https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5227-9945 Instytut Historyczny Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego Dowód na polski antysemityzm czy raczej świadectwo przełomowych czasów? (Przyczynek do stosunków polsko-żydowskich) Skomplikowane stosunki między obu narodami w XIX i XX w. od wielu już lat pozostają w centrum uwagi licznego grona historyków. Stąd na ten temat mamy relatywnie obszerną i często cenną literaturę1. Podejmują go badacze nie tylko z Polski, wielu dochodzi do odmiennych niekiedy wniosków, czasem nawet w kwestiach o dużym znaczeniu dla obu narodów2, co może wynikać z różnych przyczyn – niekiedy winne są zapewne jakieś błędy metodolo- giczne, a niekiedy być może zbyt duże zaangażowanie emocjonalne po jednej ze stron? Ta niełatwa problematyka często wzbudza duże kontrowersje, ale pomimo to warto dorzucić do niej niewielki przyczynek, z którym zetknąć się już musiało spore grono badaczy polskiego uchodźstwa niepodległościowego w latach powojennych, wertując archiwa w Instytucie Polskim i Muzeum im. gen. Sikorskiego w Londynie (IPMS)3. Jednak wymienieni historycy anali- zowali wyraźnie szersze zagadnienia – głównie relacje między polskim rządem 1 Przyk ładowo wartościowe prace publikują na te tematy m.in.: M. Wodziński, Władze Królestwa Polskiego wobec chasydyzmu. Z dziejów stosunków politycznych, Wrocław 2008; B. Szaynok, Z historią i Moskwą w tle. Polska a Izrael 1944–1968, Wrocław 2007. 2 M.J. Chodakiewicz, Żydzi i Polacy 1918–1955. Współistnienie – zagłada – komunizm, War- szawa 2000; J. Grabowski, Dalej jest noc. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski, Warszawa 2018. 3 T. Wolsza, Rząd RP na obczyźnie wobec wydarzeń w kraju 1945–1950, Warszawa 1998, s. -

Re-Thinking U.S.-Soviet Relations in 1956: Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech, the Poznán Revolt, the Return of Władysław Gomułka, and the Hungarian Revolt

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2014 Re-Thinking U.S.-Soviet Relations in 1956: Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech, the Poznán Revolt, the Return of Władysław Gomułka, and the Hungarian Revolt Emily Parsons Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Parsons, Emily, "Re-Thinking U.S.-Soviet Relations in 1956: Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech, the Poznán Revolt, the Return of Władysław Gomułka, and the Hungarian Revolt". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2014. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/365 1 Re-Thinking U.S.-Soviet Relations in 1956: Nikita Khrushchev’s Secret Speech, the Poznań Revolt, the Return of Władysław Gomułka, and the Hungarian Revolt Emily Parsons History Department Senior Thesis Advisor: Samuel Kassow Trinity College 2013-2014 2 Table of Contents: Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Part One: The Chronology of the Events of the Cold War in 1956 12 Chapter 1: Do As I Say Not As I Do: Nikita Khrushchev’s Secret Speech 13 Chapter 2: The Eastern Bloc Begins to Crack: Poznań Revolt and Polish October 21 Chapter 3: Khrushchev Goes Back on His Word: The Hungarian Revolt of 1956 39 Part Two: The United States Reactions and Understanding of the Events of 1956 60 Chapter 4: Can Someone Please Turn on the Lights? It’s Dark in Here: United States Reactions to the Khrushchev’s Secret Speech 61 Chapter 5: “When They Begin to Crack, They Can Crack Fast. -

Communist Women and the Spirit of Trans Gression: the Case of Wanda

116 m e m o r y and place Agnieszka Mrozik Communist Women and the Spirit of Trans The article w as writter gression: The Case of Wanda Wasilewska as part of the "M łody IBL" grant, which w as carried out at the Institute of Literary Research of DOI:10.18318/td.2 016.en.1.7 the Polish Academ y of Sciences between 201 a r d 20 12 . Agnieszka Mrozik - Life has to be a struggle. Assistant Professor Wanda Wasilewska, at the Institute of Dzieciństwo [Childhood]1 Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences. She is the author of Akuszerki Personal Genealogy transformacji. Kobi In her autobiographical sketch O moich książkach [AboutMy ety, literatura i władza w Polsce po 1989 roku Books] (1964), penned towards the end of her life, Wanda (2012). She has co-au Wasilewska noted: thored and co-edited PRL—życie po życiu My home schooled me well - far from a bourgeois (2013), Encyklopedia sense of contentment and bourgeois ideals, it was gender (2014), and ... czterdzieści i cztery. always focused on general affairs [...], the aura of my Figury literackie (2016). family home, where general affairs were always put She co-edited (with first, instead of personal ones, must have had an im Anna Artwińska) pact on my adult life. It was kind of a given that one „Powrót pokolenia?" Second Texts 1 (2016). should take an interest in what was going on around She is currently work them, and actively participate in l i f e . 2 ing on a book project Forgotten Revolution: Communist Female Intellectuals and the Making ofWomen's 1 Wanda Wasilewska, Dzieciństwo (W arszawa: PIW, 1967), 123. -

Detective Work Researching Soviet World War II Policy on Poland in Russian Archives (Moscow, 1994)

Cahiers du monde russe Russie - Empire russe - Union soviétique et États indépendants 40/1-2 | 1999 Archives et nouvelles sources de l’histoire soviétique, une réévaluation Detective work Researching Soviet World War II policy on Poland in Russian archives (Moscow, 1994) Anna M. Cienciala Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/13 DOI: 10.4000/monderusse.13 ISSN: 1777-5388 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 251-270 ISBN: 2-7132-1314-2 ISSN: 1252-6576 Electronic reference Anna M. Cienciala, « Detective work », Cahiers du monde russe [Online], 40/1-2 | 1999, Online since 15 January 2007, Connection on 21 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/13 ; DOI : 10.4000/monderusse.13 2011 ANNA M. CIENCIALA DETECTIVE WORK: RESEARCHING SOVIET WORLD WAR II POLICY ON POLAND IN RUSSIAN ARCHIVES (Moscow, 1994)* SOVIET POLICY ON POLAND during the Second World War has been, with a few exceptions, generally marginalized in English language studies of wartime diplomacy. This seems strange, for the borders and political system of postwar Poland were among Stalin’s major concerns. Indeed, Soviet control of Poland would ensure Soviet control of Central and Eastern Europe as well as a land bridge to Germany. As it happened, Stalin’s demands regarding Poland were a thorny issue in Anglo-Soviet relations, and sometimes a delicate one in U.S.- Soviet relations. Polish language studies on the policies of the Polish government-in-exile, its relations with Moscow, and on Polish communists, as well as specialized English language works on these subjects — including mine — were based on available Polish, British, and American sources but suffered from the lack of Russian archival material. -

The Defection of Jozef Swiatlo and the Search for Jewish Scapegoats in the Polish United Workers’ Party, 1953-1954

The Defection of Jozef Swiatlo and the Search for Jewish Scapegoats in The Polish United Workers’ Party, 1953-1954 L.W. Gluchowski The extermination of the overwhelming majority of Polish Jews in the Holocaust by the Germans in occupied Poland did not end anti-Semitism in Poland. Jewish emigration from Poland increased following the Kielce pogrom in 1946.1 It is difficult to dispute in general the conclusion that the demoralization and inhumanity experienced during the war, the transfer of some Jewish property, and the relentless Nazi racial propaganda took its toll, leaving many psychological scars on postwar Polish society.2 The òydokomuna (Jew-Communism) myth gained especially powerful resonance with the subsequent forced establishment of communist rule in Poland. The Polish version of this stereotype has its genesis in the interwar period.3 And anti-Semitism in Poland has more ancient historical antecedents. Stalin’s wartime and postwar nationalities and cadres policy, at least as applied to the Polish case, tended to prefer those who had taken Soviet citizenship and Soviet party membership as well as ‘comrades of Jewish origins’ to many important posts. Stalin did more than promote ethnic particularism among the nationalities under his control. He became an effective and ruthless manipulator of the nationality of party cadres in the Soviet party, the foreign parties of the Comintern, and later most of the ruling communist parties of Soviet-East Europe. The peculiarities and zigzags of Soviet nationality policy, which had a direct impact on cadre policies throughout the Soviet bloc, was not merely exported to the communist states of Eastern Europe. -

„Żydokomuny” W Polsce W Latach 1944–1947 – Próba Analizy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal Czasopism Naukowych (E-Journals) ZESZYTY NAUKOWE UNIWERSYTETU JAGIELLOŃSKIEGO MCCXCI – 2007 Prace Historyczne z. 134 ALEKSANDER SOŁTYSIK KONSTYTUTYWNE CECHY MITU „ŻYDOKOMUNY” W POLSCE W LATACH 1944–1947 – PRÓBA ANALIZY Mit nie ma jednej jedynej definicji, która byłaby wyczerpująca dla historii, socjolo- gii i innych nauk humanistycznych. Dlatego też, w niniejszym artykule postaram się określić, na przykładzie mitu „żydokomuny” z lat 1944–1947 w Polsce, te cechy i te zjawiska, które były i są dla niego konstytutywne. Jednym z ważniejszych źródeł, na jakich się opieram, jest prasa podziemna i ulotki, które w owym okresie, podobnie jak w czasie wojny, były narzędziem kształtowania postaw. Likwidacja Polskiego Państwa Podziemnego rozpoczęła się już w styczniu 1944 roku. Cywilne podziemie ginęło niemal równolegle do niszczonego przez Sowietów podziemia zbrojnego1. Faza likwidacji Armii Krajowej oraz ludzi związanych z pro- londyńskim obozem była realizowana przez sowieckie władze okupacyjne. Należy tutaj szczególnie zwrócić uwagę na dekret „O ochronie państwa” z 30 października 1944 roku2, który jest kwintesencją najrozmaitszych form terroru skierowanego prze- ciwko tym, którzy próbowali przeciwstawić się komunistycznemu dyktatowi3. W re- zultacie, ostatnie walki z okupantem niemieckim nałożyły się na pierwsze boje z So- wietami, a konspiracja antyniemiecka niemal automatycznie zmieniła się w tak zwaną „drugą konspirację”, która miała się zrealizować w oddolnym powstaniu antysowiec- kim i antykomunistycznym4. Świadomość polityczną Polaków po wojnie kształtowały między innymi takie fak- ty. Do łagrów w Związku Sowieckim wywieziono ponad 50 tysięcy osób. Prawdopo- dobnie od 200 tysięcy do 1 miliona osób znalazło się w więzieniach i obozach w Pol- sce5. -

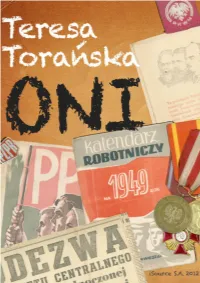

Jakub Berman

Teresa Torańska ONI Spis treści Wstęp 4 Celina Budzyńska 11 Edward Ochab 67 Roman Werfel 135 Stefan Staszewski 186 Wiktor Kłosiewicz 282 Leon Chajn 322 Julia Minc 350 Jakub Berman 369 Leon Kasman 567 Kalendarium wydarzeń 1944-1970 710 Notka bibliograficzna 760 Wstęp Tę książkę pisałam ponad cztery lata, od jesieni 1980 do końca 1984 roku. Zaczęłam po wybuchu „Solidarności”, która niosła nadzieję na wolność i radość, że ONI już przegrali, a skończyłam, gdy Polska znowu była PRL-em, dla mnie wciąż – mimo oficjalnego zniesienia – w stanie wojennym. W ZSRR po śmierci Leonida Breżniewa rządzili jego ideowi następcy: Jurij Andropow i Konstantin Czernienko, i chyba nikt nawet w naj śmielszych marzeniach nie przypuszczał, że za pięć lat rozpadnie się blok sowiecki i Polska odzyska suwerenność. Ja w każdym razie na to nie liczyłam. W stanie wojennym, po dziesięciu latach pracy w dziennikarstwie, stałam się człowiekiem wolnym od oficjalnej etatowej pracy, wolnym od zarabiania pieniędzy, planowania przyszłości i układania sobie życia. I była we mnie... wiara – zupełnie irracjonalna – że ICH wyznaniami, jeśli nie zakłócę, to skomplikuję bieg historii. Społeczeństwo dzieliło się wtedy na ONI i MY. MY byliśmy wspaniali: mądrzy, dobrzy, sprawiedliwi, zdolni do najwyższych poświęceń dla Ojczyzny, a ONI byli komunistami, którzy służyli obcemu mocarstwu (mniej lub bardziej lojalnie), wypełniali jego dyrektywy (mniej lub bardziej skrupulatnie) i kłamali, bez przerwy kłamali. ONI dla nas byli obcym ciałem, które rozpełzło się po naszym wycieńczonym drugą wojną światową organizmie, na skutek zdrady w Jałcie i klęski w Powstaniu Warszawskim, byli obcą władzą, która przyjechała na radzieckich czołgach. Wcześniej ICH nie znałam. W mojej rodzinie nie było ani jednego komunisty, nikt nie należał do partii, a do mojego rodzinnego domu przychodzili wyłącznie kresowiacy z Wileńszczyzny, Wołynia czy z Odessy, którzy system sowiecki poznali w łagrach, na zesłaniach i podczas przesiedleń. -

When Speaking of Jewish Communists in Postwar Poland It Is

The Others 181 7 THE OTHERS When speaking of Jewish Communists in postwar Poland it is necessary to differentiate between Communists of Jewish origin, functioning in various sectors of the Party and the State apparatus, and Jewish Communists active in the Jewish milieu. Devoted and experienced prewar Polish-Jewish Communists were indispensable to the regime during its fi rst postwar years. Some of them, like Jakub Berman, Hilary Minc and Roman Zambrowski, occupied its highest ranks. Then there were the numerous younger Jews, the new recruits, who were considered to be loyal and were offered excellent opportunities for social promotion. For reasons stemming from postwar Polish mono-ethnicity and prevailing anti-Semitic attitudes, upwardly mobile Jews were expected to Polonize. This meant, usually, changing names and severing contacts with Jewish life. A large proportion of young Jewish men found non-Jewish spouses. All this meant, of course, further assimilation. Most of them followed this path willingly, and were quite enthusiastic about their future. A Jew could now become a high-ranking Party or Security offi cial or a senior army offi cer. Jewish intellectuals and scholars took part in the cultural and academic life of postwar Poland, and young Jewish men and women enrolled in the universities. Quite naturally, therefore, Jewish administrators, professionals and students tended to concentrate in large urban centers such as Warsaw, Krakow and Lodz.1 Whereas Zionist-oriented Jews joined kibbutzim and Zionist parties, the political framework of Communist-oriented “Jewish” Jews was the Frakcja, the Jewish Fraction of the PPR. Most of the leaders and activists of the Fraction had survived the war in the Soviet Union and looked forward to the reconstruction of Jewish social, cultural and economic life in Communist Poland. -

The Case of Wanda Wasilewska

Teksty Drugie 2016, 1, s. 116-143 Special Issue – English Edition Communist Women and the Spirit of Transgression: The Case of Wanda Wasilewska Agnieszka Mrozik http://rcin.org.pl 116 memory and place Agnieszka Mrozik Communist Women and the Spirit of Trans- The article was written as part of the “Młody IBL” gression: The Case of Wanda Wasilewska grant, which was carried out at the Institute of Literary Research of DOI:10.18318/td.2016.en.1.7 the Polish Academy of Sciences between 2011 and 2012. Agnieszka Mrozik – Life has to be a struggle. Assistant Professor Wanda Wasilewska, at the Institute of Dzieciństwo [Childhood]1 Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences. She is the author of Akuszerki Personal Genealogy transformacji. Kobi- In her autobiographical sketch O moich książkach [About My ety, literatura i władza w Polsce po 1989 roku Books] (1964), penned towards the end of her life, Wanda (2012). She has co-au- Wasilewska noted: thored and co-edited PRL—życie po życiu My home schooled me well – far from a bourgeois (2013), Encyklopedia sense of contentment and bourgeois ideals, it was gender (2014), and … czterdzieści i cztery. always focused on general affairs […], the aura of my Figury literackie (2016). family home, where general affairs were always put She co-edited (with first, instead of personal ones, must have had an im- Anna Artwińska) pact on my adult life. It was kind of a given that one „Powrót pokolenia?” should take an interest in what was going on around Second Texts 1 (2016). She is currently work- them, and actively participate in life…2 ing on a book project Forgotten Revolution: Communist Female Intellectuals and the Making of Women’s 1 Wanda Wasilewska, Dzieciństwo (Warszawa: PIW, 1967), 123. -

September 01, 1945 Jakub Berman's Letter to Stalin: a Report on the Situation in Poland and Request for Advice and Help

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 01, 1945 Jakub Berman's Letter to Stalin: A Report on the Situation in Poland and Request for Advice and Help Citation: “Jakub Berman's Letter to Stalin: A Report on the Situation in Poland and Request for Advice and Help,” September 01, 1945, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Jakub Berman Collection, 325/33, pp. 22-26, Hoover Institution Archives. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/134357 Summary: Jakub Berman, leading Polish communist, writes to Stalin a detailed list of events occuring in Poland dealing with the stability of the Post-War communist government. Original Language: English Contents: English Transcription Jakub Berman's Handwritten Notes of a Conversation with Stalin or a Letter to Stalin: a Report on the Situation in Poland and Request for Advice and Help, 1945 September (first half) The situation in Poland within the last two weeks has been marked by numerous symptoms of rising political tension and growing pressures of reactionary forces under the influence of external and internal factors of a new configuration of political forces. This situation is potent with serious dangers and calls for a fast breakthrough. That is why we are writing to you this letter with a request for advice and assistance. 1. There are signs of dissatisfaction among the working class, which already finds expression not only in strikes lasting an hour or a few hours (particularly in Lodz, the coal mining region, Zawiercie, on the railroads), counted already in scores, but even in the form of a general strike, as e.g.