How Strategies for Peace Operations Are Developed and Implemented

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peacekeeping Interventions in Africa

d Secur n ity a e S c e a r i e e s P FES Gavin Cawthra Peacekeeping Interventions in Africa “War is Peace, Freedom is Slavery, Ignorance is Strength.” About The Author Professor Gavin Cawthra holds the Chair in Defense and Security Management at the Graduate School of Public and Development Management (P&DM) at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. He is former Director of the Graduate School of Public and Development Management, and was previously coordinator of the Military Research Group, Director of the Committee on South African War Resistance, and Research Officer at the International Defense and Aid Fund (UK). Professor Gavin Cawthra holds PhD from King’s College, University of London and BA Honours from the University of Natal. He has published numerous books as well as journal articles in the area of security studies. His publications have been translated into several languages. Mr. Cawthra has lectured in more than 20 countries all over Africa and does regularly consultancies for governments, NGOs and international organisations. Part of this briefing is drawn from the findings of a research project carried out under the leadership of the author, made possible by a Social Science Research Council African Peacekeeping Network (APN) research grant, with funds provided by Carnegie Corporation of New York. Cover Art How have we become mere voters and passive participants instead of shaping our own destiny? This is the question that Mozambican artist, Nelsa Guambe, asks in her current exhibition, “Status quo”. The paintings reflect on the current situation of the country, on collective debt, political conflict, devaluation of the local currency Metical and roaring inflation. -

Martin Shichtman Named Director of EMU Jewish Studies

Washtenaw Jewish News Presort Standard In this issue… c/o Jewish Federation of Greater Ann Arbor U.S. Postage PAID 2939 Birch Hollow Drive Ann Arbor, MI Federation Biking 2010 Ann Arbor, MI 48108 Permit No. 85 Main Event Adventure Election In Israel Results Page 5 Page 7 Page 20 December 2010/January 2011 Kislev/Tevet/Shevat 5771 Volume XXXV: Number 4 FREE Martin Shichtman named director of EMU Jewish Studies Chanukah Wonderland at Geoff Larcom, special to the WJN Briarwood Mall Devorah Goldstein, special to the WJN artin Shichtman, a professor of Shichtman earned his doctorate and mas- English language and literature ter’s degree from the University of Iowa, and What is white, green, blue and eight feet tall? M who has taught at Eastern Michi- his bachelor’s degree from the State Univer- —the menorah to be built at Chanukah Won- gan University for 26 years, has been appointed sity of New York, Binghamton. He has taught derland this year. Chabad of Ann Arbor will director of Jewish Studies for the university. more than a dozen courses at the graduate sponsor its fourth annual Chanukah Wonder- As director, Shichtman will create alliances and undergraduate levels at EMU, including land, returning to the Sears wing of Briarwood with EMU’s Jewish community, coordinate classes on Chaucer, Arthurian literature, and Mall, November 29–December 6, noon–7 p.m. EMU’s Jewish Studies Lecture Series and de- Jewish American literature. Classes focusing New for Chanukkah 2010 will be the building of velop curriculum. The area of Jewish studies on Jewish life include “Imagining the Holy a giant Lego menorah in the children’s play area includes classes for all EMU students inter- Land,” and “Culture and the Holocaust.” (near JCPenny). -

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire Host on 'Worst Year'

7 Ts&Cs apply Iceland give huge discount Claire King health: Craig Revel Horwood Kate Middleton pregnant Jenny Ryan: ‘The cat is out to emergency service Emmerdale star's health: ‘It was getting with twins on royal tour in the bag’ The Chase quizzer workers - find… diagnosis ‘I was worse’ Strictly… Pakistan?… announces… Jeremy Clarkson: ‘Wanted to top myself’ Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on 'worst year' JEREMY CLARKSON - who fronts ITV show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? - shared his thoughts on a recent study which claimed 1978 was the “worst year” in British history. Who Wants to Be a Millionaire: Jeremy criticises the contestant Earlier this week, researchers from Warwick University claimed people of Britain were at their most unhappy in 1978. The latter year and the first two months of 1979 are best remembered for the Winter of Discontent, where strikes took place and caused various disruptions. ADVERTISING 1/6 Jeremy Clarkson (/search?s=jeremy+clarkson) shared his thoughts on the study as he recalled his first year of working during the strikes. PROMOTED STORY 4x4 Magazine: the SsangYong Musso is a quantum leap forward (SsangYong UK)(https://www.ssangyonggb.co.uk/press/first-drive-ssangyong-musso/56483&utm-source=outbrain&utm- medium=musso&utm-campaign=native&utm-content=4x4-magazine?obOrigUrl=true) In his column with The Sun newspaper, he wrote: “It’s been claimed that 1978 was the worst year in British history. RELATED ARTICLES Jeremy Clarkson sports slimmer waistline with girlfriend Lisa Jeremy Clarkson: Who Wants To Be A Millionaire host on his Hogan weight loss (/celebrity-news/1191860/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-girlfriend- (/celebrity-news/1192773/Jeremy-Clarkson-weight-loss-health- Lisa-Hogan-pictures-The-Grand-Tour-latest-news) Who-Wants-To-Be-A-Millionaire-age-ITV-Twitter-news) “I was going to argue with this. -

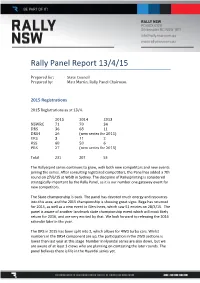

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

U.N. Peacekeeping Operations in Africa

U.N. PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS IN AFRICA HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION April 30, 2019 Serial No. 116–30 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/, http://docs.house.gov, or http://http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–134PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York, Chairman BRAD SHERMAN, California MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas, Ranking GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York Member ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida JOE WILSON, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts TED S. YOHO, Florida DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois AMI BERA, California LEE ZELDIN, New York JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas JIM SENSENBRENNER, Wisconsin DINA TITUS, Nevada ANN WAGNER, Missouri ADRIANO ESPAILLAT, New York BRIAN MAST, Florida TED LIEU, California FRANCIS ROONEY, Florida SUSAN WILD, Pennsylvania BRIAN FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania DEAN PHILLIPS, Minnesota JOHN CURTIS, Utah ILHAN OMAR, Minnesota KEN BUCK, Colorado COLIN ALLRED, Texas RON WRIGHT, Texas ANDY LEVIN, Michigan GUY RESCHENTHALER, Pennsylvania ABIGAIL SPANBERGER, Virginia TIM BURCHETT, Tennessee CHRISSY HOULAHAN, Pennsylvania GREG PENCE, Indiana TOM MALINOWSKI, -

INTRODUCING the TOP GEAR LIMITED EDITION BUGG BBQ from BEEFEATER Searing Performance for the Meat Obsessed Motorist

PRESS RELEASE INTRODUCING THE TOP GEAR LIMITED EDITION BUGG BBQ FROM BEEFEATER Searing Performance for the Meat Obsessed Motorist “It’s Flipping Brilliant” Sydney, Australia, 19 November 2012 BeefEater, the Australian leaders in barbecue technology, has partnered with BBC Worldwide Australasia to create an innovative and compact Top Gear Limited Edition BUGG® (BeefEater Universal Gas Grill) BBQ, that will make you the envy of your mates. The Limited Edition BBQ from BeefEater comes with an exclusive Top Gear accessory bundle which includes a Stig oven mitt and apron to help you look the part while cooking. It also features a bespoke Top Gear gauge and tyre‐track temperature control knob to keep you on track whilst perfecting your meat. ‘Top Gear’s Guide on How Not to BBQ’ is also included, with helpful tips such as ‘do not attempt to modify your barbecue by fitting an aftermarket exhaust’ and ‘this barbecue is not suitable for children, or adults who behave like children’ guiding users through those trickier BBQ moments. The BBQ launches in Australia just in time for Christmas at Harvey Norman and other leading independent retailers, and will be available in the UK and Europe when the weather’s a little better. “A cool white hood, precision controls, bespoke gauges and a high performance ignition – what a way to convince the meat obsessed motorist to get out of the garage and cook dinner! This new Top Gear Limited Edition BUGG BBQ from BeefEater is a high performance vehicle, making cooking ability an optional extra,” says Elie Mansour, BBC Worldwide Australasia’s Manager Licensed Consumer Products. -

Investigation Into the the Accident of Richard Hammond

Investigation into the accident of Richard Hammond Accident involving RICHARD HAMMOND (RH) On 20 SEPTEMBER 2006 At Elvington Airfield, Halifax Way, Elvington YO41 4AU SUMMARY 1. The BBC Top Gear programme production team had arranged for Richard Hammond (RH) to drive Primetime Land Speed Engineering’s Vampire jet car at Elvington Airfield, near York, on Wednesday 20th September 2006. Vampire, driven by Colin Fallows (CF), was the current holder of the Outright British Land Speed record at 300.3 mph. 2. Runs were to be carried out in only one direction along a pre-set course on the Elvington runway. Vampire’s speed was to be recorded using GPS satellite telemetry. The intention was to record the maximum speed, not to measure an average speed over a measured course, and for RH to describe how it felt. 3. During the Wednesday morning RH was instructed how to drive Vampire by Primetime’s principals, Mark Newby (MN) and CF. Starting at about 1 p.m., he completed a series of 6 runs with increasing jet power and at increasing speed. The jet afterburner was used on runs 4 to 6, but runs 4 and 5 were intentionally aborted early. 4. The 6th run took place at just before 5 p.m. and a maximum speed of 314 mph was achieved. This speed was not disclosed to RH. 5. Although the shoot was scheduled to end at 5 p.m., it was decided to apply for an extension to 5:30 p.m. to allow for one final run to secure more TV footage of Vampire running with the after burner lit. -

Sanford Bernstein's 9Th Annual Strategic Decisions

André Lacroix Group Chief Executive Distributor and retailer for the world’s leading automotive brands Right Markets: Right Categories: 2/3 revenues Five distinct from Asia Pacific revenue streams & Emerging offering growth / Markets defensive mix Right Brands: Right Financials: 90% of profits Attractive growth from 6 leading prospects, strong premium cash generation & OEMs robust balance sheet Distinct and attractive business model in the automotive sector 3 4 Majority of global growth in population and GDP will come from Asia Pacific and Emerging Markets Western Europe Eastern Europe & Russia North America GDP 2012: $16,847bn GDP 2012: $4,870bn GDP 2012: $17,414bn Growth 2012-17: + $2,708bn Growth 2012-17: + $2,292bn Growth 2012-17: + $4,431bn Pop 2012: 413m Pop 2012: 449m Pop 2012: 350m Growth 2012-17: + 7m Growth 2012-17: + 1m Growth 2012-17: + 17m Middle East GDP 2012: $2,559 bn Growth 2012-17: + $616bn Pop 2012: 231m Growth 2012-17: + 26m Africa Asia & Oceania South & Central America GDP 2012: $2,069bn GDP 2012: $22,350bn GDP 2012: $5,788bn Growth 2012-17: + $777bn Growth 2012-17: + $9,497bn Growth 2012-17: + $1,811bn Pop 2012: 1,060m Pop 2012: 3,858m Pop 2012: 584m Growth 2012-17: + 132m Growth 2012-17: + 199m Growth 2012-17: + 35m Source: IMF (nominal GDP, population) Updated Sept 2012 Asia Pacific and Emerging Markets will represent 94% of population growth 2012 – 17 and 71% of GDP growth 5 …this pattern is reflected in car industry growth Western Europe Eastern Europe & Russia North America TIV 2012 13.2m TIV 2012 5.1m TIV 2012 -

PM Vows Support to Private Sector

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Sharapova can play again in INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-6, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 Commercial Bank launches REGION 7, 8 BUSINESS 1-7, 13–16 April aft er fi rst Visa Signature credit 18,168.45 10,388.18 49.19 ARAB WORLD 8 CLASSIFIED 8-12 -85.40 +78.26 +0.38 INTERNATIONAL 9-21 SPORTS 1 – 8 card for Qatar SMEs ban reduced -0.47% +0.76% +0.78% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 WEDNESDAY Vol. XXXVII No. 10232 October 5, 2016 Muharram 4, 1438 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals PM vows support In brief to private sector QATAR | Tragedy Companies suggest ways to Minister of Municipality and Environ- ticipate in all of the country’s economic Two QU female improve business ment, who along with other ministers, activities, and highlighted changes to students drown was present at the meeting. the visa and transit visas as an example By Santhosh V Perumal The Prime Minister said Qatar was of these eff orts. An investigation is under way into Business Reporter one of the biggest countries in terms of The government will also help in the death of two female students of spending on national projects. Spending facilitating the process of obtaining Qatar University (QU) on Monday on major projects touched QR56bn in working visas to allow the private sec- evening, according to a report on atar, which was recently ranked the fi rst six months of the year. The past tor to obtain its needs from the job Al Sharq news website. -

Media Release

Hon George Souris MP Hon Graham Annesley MP Minister for Tourism, Major Events Minister for Sport and Recreation Hospitality and Racing Minister for the Arts MEDIA RELEASE Monday 29 October, 2012 NSW SECURES TOP GEAR FESTIVAL Minister for Tourism and Major Events, George Souris, today announced that Sydney has won the right to stage the Top Gear Festival for the next three years. “The NSW Government, through Destination NSW, successfully bid for this event in conjunction with the Australian Racing Drivers’ Club (ARDC). Sydney will be hosting the popular and high profile festival from 2013 through to 2015,” Mr Souris said. “The exclusive Australasian staging of Top Gear Festival Sydney will take place at Sydney Motorsport Park, Eastern Creek over the weekend of 9th and 10th March, 2013, one week prior to the Formula One Australian Grand Prix in Melbourne. “The Top Gear Festival has been held only twice before, both times in South Africa in 2011 and June of this year. “This unique motoring festival is based on the internationally renowned Top Gear television programme, which was recently named by Guinness World Records as the world’s most widely watched factual TV show, having been viewed by audiences in 244 different territories around the globe. “It is yet another example of NSW Government securing major events and ensuring the State remains number one”. Minister for Sport, Graham Annesley, said: “The Top Gear brand is a worldwide phenomenon and the staging of the Festival in Western Sydney for the next three years will generate countless opportunities for NSW and more importantly local businesses. -

Counterinsurgency in Pakistan

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY institution that helps improve policy and POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY decisionmaking through research and SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY analysis. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND Support RAND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Counterinsurgency in Pakistan Seth G. Jones, C. Christine Fair NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Project supported by a RAND Investment in People and Ideas This monograph results from the RAND Corporation’s Investment in People and Ideas program.