1 Cooperation and Integration in African The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Number 15/16 Contents

Number 15/16 Contents May-December 1979 Editorial 1 Editorial Working Group Underdevelopment in Northern Ghana: Natural Causes or Colonial Capitalism? Chris Allen Manfred Bienefeld Nii-K Plange 4 Lionel Cliffe Contradictions in the Peripheralization Roben Cohen of a Pastoral Society: the Maasai Erica Flegg Mejid Hussein Hans Hedlund 15 Duncan Innes Rural Class Formation and Ecological Peter Lawrence Collapse in Botswana Roger Leys Lionel Cliffe and Richard Moorsom 35 Gavin Williams Editorial Staff Capitalism and Hunger in Northern Nigeria Doris Burgess Judy Mohan Bob Shenton and Mike Watts 5 3 Overseas Editors Dependent Food Policy in Nigeria 1975-1979 Cairo: Shahida El Baz Kampala: Mahmood Mamdani Okello Oculi 63 Maputo: Ruth First Capitalist Organization of Production Stockholm: Bhagavan through non-Capitalist Relations: Toronto: Jonathan Barker, John Saul Women's Role in a Pilot Resettlement Washington: Meredeth Turshen in Upper Volta Zaria: Bjorn Beckman Anna Conti 75 Contributing Editors Basil Davidson Class Formation in the Peasant Sam Geza Economy of Southern Ghana Thomas Hodgkin Emile Vercruijsse 93 Charles Kallu-Kalumiya Peasant Fishermen and Capitalists: Mustafa Khogali Colin Leys Development in Senegal Robert Van Lierop Klaas de Jonge 105 Archie Mafeje Briefings Prexy Nesbitt The Zimbabwe Elections 124 Claude Meillassoux Ken Post Notes on the Workers' Strikes in Subscriptions (3 issues) Mauritius 130 UK & Africa Debates Individual £4.00 Relations of Production, Class Struggle Institutions £8.00 and the State in South Africa in the Elsewhere Individuals £4.50 Inter-war Period 135 Institutions £10.00 Swaziland: Urban Local Government Students £ 3.00 (payable in Subjugation in the Post-Colonial sterling only) State 146 Airmail extra Europe £2.00 In Defence of the MPLA and the Zone A £2.50 Angolan Revolution 148 £3.50 Zone B On Peasantry and the 'Modes of Zone C £4.00 Single copies Production' Debate 154 Individuals £1.50/$4.00 Reviews 162 Institutions £ 3.00/38.00 Current Africana 174 Note: Please add $2 for each non- sterling cheque Giro no. -

Reviving Makerere University to a Leading Institution for Academic Excellence in Africa

Reviving Makerere University to a Leading Institution for Academic Excellence in Africa Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of The 3rd State of the Nation Platform December 4, 2009 Kampala, Uganda Bernard Tabaire Jackie Okao Reviving Makerere University to a Leading Institution ACODE Policy Dialoguefor AcademicSeries Excellence No. in Africa8, 2010 Table of Content List of Acronyms................................................................................................ .ii 1.Introduction..................................................................................................... 1 2.Summarry of Discussion............................................................................... 3 2.1 Financial Performance.........................................................................3 2.2 Research and Knowledge Management.......................................... .4 2.3 Quality of Service Delivery............................................................. .5 2.4 Management/Staff Relations.......................................................... 6 2.5 University/ Student Relations.......................................................... 6 2.6 University/Government Relations.................................................... 8 2.7 University Image and Standing......................................................... 8 2.8 Governance........................................................................................... 9 3. Issues to Ponder.......................................................................................... -

2- Oculi.Pmd 13 20/08/2011, 11:02 14 Africa Development, Vol

Africa Development, Vol. XXXVI, No.1, 2011, pp. 13–28 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa, 2011 (ISSN 0850-3907) The Role of Economic Aspiration in Elections in Kenya Okello Oculi* Abstract The violence that erupted, following the 30 December 2007 civic, parliamentary and presidential elections in Kenya is analysed as part of various historical continua anchored on social engineering by colonial officials who sought to control social change after the Mau Mau conflict. Presidents Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi built on this colonial strategy for managing challenges by socialist and pro-democracy forces to their hold on power. Moi’s regime had to combat challenges to his electoral fortunes from 1988 onwards and left behind a technology that was a useful investment for 2007/2008 opposition groups. Both forms of social engineering gave prominence to tribalism as an organising tool. The power behind the success of these exercises was economic anxieties rooted in land, widespread unemployment and elite struggles for control of political influence. This perspective allows us to propose that stability in Kenya in the post-conflict period requires a bold counter-social engineering that breaks down efforts to continue the use of tribalism to prevent re-distribution of large landed estates in several parts of the country, particularly Coast and Central Provinces. Résumé Les violences qui ont éclaté à la suite des élections municipales, législatives et présidentielles qui ont eu lieu le 30 décembre 2007 au Kenya sont analysées dans le cadre de divers continuums historiques fondés sur l’ingénierie sociale de responsables coloniaux qui cherchaient à contrôler le changement social après le conflit mau-mau. -

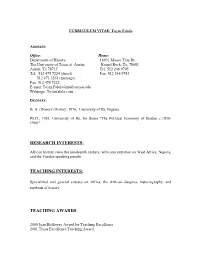

Teaching Interests

CURRICULUM VITAE: Toyin Falola ADDRESS: Office: Home: Department of History, 16931 Mouse Trap Dr. The University of Texas at Austin, Round Rock, Tx, 78681 Austin, Tx 78712 Tel: 512 246 9705 Tel: 512 475 7224 (direct) Fax: 512 246 9743 512 471 3261 (message) Fax: 512 475 7222 E-mail: [email protected] Webpage: Toyinfalola.com DEGREES: B. A. (Honors) History, 1976, University of Ife, Nigeria. Ph.D., 1981, University of Ife, for thesis "The Political Economy of Ibadan, c.1830- 1900." RESEARCH INTERESTS: African history since the nineteenth century, with concentration on West Africa, Nigeria, and the Yoruba-speaking people. TEACHING INTERESTS: Specialized and general courses on Africa, the African diaspora, historiography, and methods of history. TEACHING AWARDS: 2000 Jean Holloway Award for Teaching Excellence 2001 Texas Excellence Teaching Award 2003 Chancellor’s Council Outstanding Teaching Award 2004 Academy of Distinguished Teachers MEMOIR A Mouth Sweeter Than Salt: An African Memoir (University of Michigan Press, August 2004) FESTSCHRIFTEN Adebayo Oyebade, ed., The Transformation of Nigeria: Essays in Honor of Toyin Falola (Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 2002). Pp. xi+639. Adebayo Oyebade, ed., The Foundations of Nigeria: Essays in Honor of Toyin Falola (Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 2003), pp. vii: 697. Akin Ogundiran, ed., Precolonial Nigeria: Essays in Honor of Toyin Falola (Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 2005,), pp. xi+ 556. COMMENTARIES AND WORKSHOPS ON TOYIN FALOLA “Toyin Falola on African Nationalism” Panel at a conference on Race, Ethnicity and Place Conference, Texas State University, Nov. 1-3, 2006. International Conference on the Works of Toyin Falola, Nigeria, 2003. -

Speaking in Song: Power, Subversion and the Postcolonial Text

HELEN NABASUTA MUGAMBI Speaking in Song / 421 Marjorie Macgoye's MakeltSingandOtherPoems (2000), and Micere Mugo's My Mother's Song and Other Poems (2001), all support the viewpoint that song is Speaking in Song: Power, Subversion increasing in visibility in its real, conceptual, and metaphoric manifestations. Indeed, the reverberation of song in East Africa is so prevalent that critics and the Postcolonial Text speak of a "song school" of literature, pioneered by Okot p'Bitek's Song of Lawino (1966).2 Nevertheless, despite this overwhelming presence of song, critical exploration of the oral tradition in literature has generally centered The crucial function of language as a medium of power demands around other components of the oral tradition such as folktales and proverbs, that postcolonial writing define itself by seizing the language of the at the exclusion of song. Examining song in the written literatures, particularly center and re-placing it in a discourse fully adapted to the colonized as re-placement strategy suggested here, constitutes one way of con- place. (Ashcroft et al., Empire Writes Back 39) ceptualizing song as a serious aspect of postcolonial theory. The idea of song as re-placement strategy resonates with studies such as Because song is one of the most pervasive oral forms in Africa, it is possible those in Derek Wright's anthology, Contemporary African fiction (1997), which that postcolonial writers' frequent recourse to this genre constitutes a mode of re-placement, as referred in the opening quotation. Re-placement is deemed to have explored the ideological intersections of oral and written forms even mean idiomatic relocation signifying (re)placement. -

For African Studies. Association 'Members

FOR AFRICAN STUDIES. ASSOCIATION 'MEMBERS VOLUME XXII JULY/SEPTEMBER 1989 No.3 T ABLE OF CONTENTS Board of Directors 2 From the Secretariat 2 Letters 3 Board Nominations 5 Provisional Minutes Board of Directors 5 Archives-Libraries Committee 15 CAFLIS 15 Guidelines for Librarians Interacting with South Africa 19 i 1 The Book Famine: Opportunities/or Reciprocal I Self-Interest, by Gretchen Walsh 22 I ,j AAASIACLS Sub-Saharan Africa Journal Distri ;I bution Program, by Lisbeth A. Levey 24 1 ~ Future Meetings and Calls for Papers 28 Recent Meetings 29 Awards and Fellowships 30 Employment 31 New Publications from Overseas 32 i Search for Directories on Science and Technology 34 Recent Doctoral Dissertations 35 International Visitors Program 48 I Preliminary Program, ASA Annual Meeting 51 i 2 ASA BOARD OF DIRECTORS OFFICERS President: Simon Ottenberg (University of Washington) Vice-President: Ann Seidman (Clark University) Past President: Nzongola-Ntalaja (Howard University) RETIRING IN 1989 Mario J. Azevedo (University of North Carolina at Charlotte) Pauline H. Baker (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) Allen F. Isaacman (University of Minnesota) RETIRING IN 1990 Sandra Barnes (University of Pennsylvania) Iris Berger (State University of New York at Albany) K wabena Nketia (University of Pittsburgh) RETIRING IN 1991 Martha A. Gephart (Social Science Research Council) Catharine Newbury (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) Sulayman S. Nyang (Howard University) FROM THE SECRET ARIA T ... The feverish pace in the secretariat this summer reflects the heat of the Georgia out of-doors. As organizational center for the 1989 Annual Meeting, we bustle with activi ty. A whole wall is covered with newsprint charts recording room assignments. -

The Social Function of Poetry in Underdeveloped Society: an East African Experience

(i) "THE SOCIAL FUNCTION OF POETRY IN UNDERDEVELOPED SOCIETY: AN EAST AFRICAN EXPERIENCE" By |a hm a t t e u r s , A. D. THESIS HAS BEEN ACCEPTED FOR THE E C M ■ A ( AND A QZZ'l LL17 12 PLACED LI iME UNIVERSAL LLLRAdX A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PART FULFILMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (LITERATURE) IN THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI, 1979. (ii) This thesis is ny original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University. This thesis has been sufamitted for examination with our approval as University Supervisors Mr. G. R. Gacheche First Supervisor A k — Mr. A. I. Luvai Second Supervisor i i i TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Title cf the T h e s i s ------------------- i Declaration---------------------------- ** Acknowledgement ------------------------ iv Abs t r a c t ---------------------- v CHAPTER ONE Introduction -------------------------- 1 CHAPTER TWO The Anti-social Function of Taban's and Multi ' s P o e t r y --------------------- 26 CHAPTER THREE The New Ereed of Poets: Ntiru and A n g i r a -------------------------------- 56 CHAPTER FOUR Okot p'Bitek and Okello Oculi ------------ 87 CHAPTER FIVE Conclusion---------------------------- 133 NOTES ------------------------------------- 147 BIBLIOGRAPHY----------------------------- 161 (iv) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My heartfelt thanks go to the University of Nairobi for their NORAD Scholarship which enabled me to undertake this research course. I would also like to express my special thanks to my supervisors: Mr. G. R. Gacheche and Mr. A. I. Luvai for the sacrifice they made through fruitful discussions and helpful comments. In this respect, the entire staff of Literature Department deserve credit for the encouraging concern they showed in my work. -

Discourses on Civil Society in Kenya

Discourses on Civil Society in Kenya © African Research and Resource Forum(ARRF) Published 2009 by African Research and Resource Forum (ARRF) P.O. Box 57103 00200 Nairobi, Kenya www.arrforum.org All rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in books and critical reviews. ISBN: 9966 7062 7 5 Printed in Kenya by Morven Kester (EA) Ltd TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgements Section I: Civil Society in Kenya Reflections on Civil Society Driven Change : An Overview Alioune Sall 1 Civil Society and Transition Politics in Kenya: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives Peter Wanyande 8 The Prospects of Civil Society Driven Change in Kenya Margaret K. Chemengich 20 The Role of Academia in Democratization in Kenya Charles Olungah 31 The Contribution of Academia and Civil Society in Development Policy Making & Budgetary Process Ben Sihanya 40 Section II: Civil Society In Africa: A Comparative Analysis University Students and Civil Society in Nigeria Okello Oculi 65 Civil Society and Transition Politics in Ethiopia Merera Gudina 84 Reflections on Democracy and Civil Society in Zanzibar Haroub Othman 95 PREFACE The African Research and Resource Forum (ARRF) is a regional policy research institute based in Nairobi with a focus on the most critical governance, security and development issues in Eastern Africa. All the governments in Eastern Africa have introduced national governance reforms, with varying degrees of success in the past one and a half decades. In that process, the role that civil society should play in improving the quality of governance and the lives of ordinary citizens has been an issue of great concern to the governments of the region, civil society groups, donors, academics and the voters. -

Political Economy of Development: Discussion and Analysis of the Nigerian Federal Government Development Policies on Agriculture Over the Period: 1975-1985

POLITICAL ECONOMY OF DEVELOPMENT: DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS OF THE NIGERIAN FEDERAL GOVERNMENT DEVELOPMENT POLICIES ON AGRICULTURE V OVER THE PERIOD: 1975—1985 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY IBRAHIM M. WAZIRI ATLANTA, GEORGIA MAY 1989 J (c) 1989 Ibrahim M. Waziri All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ECONOMICS WAZIRI, IBRkHIM M. B.S. OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1983 POLITICAL ECONOMY OF DEVELOPMENT: DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS OF THE NIGERIAN FEDERAL GOVERNMENT DEVELOPMENT POLICIES ON AGRICULTURE OVER THE PERIOD: 1975-1985 Advisor: Dr. Charlie Carter Thesis dated May, 1989 What will be discussed in this study is the impacts of the Federal Government Development Policies on agricultural output over the period 1975—1985. The writer attempted to examine the third and fourth National Development Plans; the Agricultural Policy on Marketing; the Import Policy; and the credits policy. These policies were discussed and analyzed. After that the trends of agricultural output were also discussed and analyzed. The result obtained from this study is that even though government had policy objects that addressed the need for rapid growth of agricultural output, the policy did not bring the growth needed for agricultural output. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LISTOFTABLES ..• iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem . 11 Hypotheses . 13 Organization...... 15 II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE 17 III. METHODOLOGY 40 D a t a S our ce s . 4 5 Objective . 45 Importance of Study . 45 IV. DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS OF THE NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLANS . 47 First National Development Plan 1962—1968 49 Second National Development Plan 1970—1974 50 Third National Development Plan 1975—1980 57 Fourth National Development Plan 1981—1985 64 V. -

Makerere's Myths, Makerere's History: a Retrospect

JHEA/RESA Vol. 6, No. 1, 2008, pp.11–39 © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa 2008 (ISSN 0851–7762) Makerere’s Myths, Makerere’s History: A Retrospect Carol Sicherman* Abstract Stemming from the author’s experience of writing a history of Makerere, this paper examines how the myths that have grown up around the university in the eighty-five years since its founding have obscured a clear view of the evolving institution, which the paper defines as ‘a university in Africa’ rather than ‘an African university’. The first myth, of an egalitarian paradise enjoyed by fully- funded students, was questioned even during its heyday by intellectuals disillu- sioned by the failure during the 1960s to fulfil the late-colonial dream. In the aftermath of the tormented 1970s and 1980s, a variant myth declared that new funding formulas made Makerere even more egalitarian. Proponents of this myth claimed that anyone who qualified for admission could attend; however, since government scholarships went to increasingly smaller proportions of the student body, only those who could raise the necessary funds themselves could take ad- vantage of the supposedly widened access. After questioning the meaning of ‘Af- rican’ in a socio-political context still strongly flavoured by foreign influence, the paper moves to consider the challenges that researchers may encounter in writing about universities in Africa: challenges that differ according to whether the re- searcher is an insider or outsider. The paper ends by asking what African academ- ics can do to rid Makerere of the diseases threatening its institutional health. -

Rethinking Global Security: an African Perspective?

SAMUEL M. MAKINDA Rethinking Global Security: An African Perspective? Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office, East and Horn of Africa, Nairobi RETHINKING GLOBAL SECURITY: AN AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE?i AFRICAN THINKERS AND THE GLOBAL SECURITY AGENDA Published 2006 by Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office for East Africa and Horn of Africa Forest Road P.O. Box 10799-00100, GPO, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: (254-20) 3744227 Fax: (254-20) 3749132 Email: [email protected] Heinrich Böll Stiftung Hackesche Höfe Rosenthaler Str. 40-41 D-10178 Berlin Tel: (49) 0303 285 340 Fax: (49) 030 285 34 109 Email: [email protected] ISBN 9966 - 9772 - 7 - 9 © 2006 Heinrich Böll Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations in books and critical reviews. For information, write to Heinrich Böll Foundation. Opinions expressed are the responsibility of the individual authors and do not necessarily constitute the official position of Heinrich Böll Foundation. Proofreading and Indexing by Damary Odanga Designed and typeset by Damary Odanga Production by WordAlive Publishers Limited ii RETHINKING GLOBAL SECURITY : AN AFRICAN PERSPECTIVE ? SAMUEL M. MAKINDA Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................... v Global Security Agenda Setting State of the World 2005: Redefining security..................................................... 1 Michael Renner Security in our one world .................................................................................. -

Profile FEMRITE and the Politics of Literature in Uganda Goretti Kyomuhendo Introduction to Talk About FEMRITE Is to Talk About

Profile FEMRITE and the Politics of Literature in Uganda Goretti Kyomuhendo Introduction To talk about FEMRITE is to talk about Uganda's literary scene, about Ugandan politics, and especially about the connections between women, politics and writing in Uganda. FEMRITE was born in 1996 out of a dream, an idea hatched by a handful of women who had either already published, or were struggling to write and publish. The dream these women had was to see more Ugandan creative women writers in print, and especially to see more evidence in print of women's visions of post-colonial freedom. At the time, there were hardly any support systems for writers, either women or men, and the entire book industry was in need of revitalisation. There was only one indigenous mainstream publishing house in the country - Fountain Publishers. For those who lived in Uganda during the sixties and early seventies, this scenario was shocking; this period had witnessed enormous literary output, and during that time, tremendous enthusiasm had been generated around literary activity. But the vibrant literary activity of the time was driven by men, and revolved around men's writing. What we see in Uganda's literary history is a pattern in which, during the first years after independence, the dominance of men's voices went unchallenged. But since the late 1990s, with the emergence of new public debates and political struggles, women's voices have become increasingly prominent. Today, women are playing an important role in creating publishing platforms, developing different literary perspectives and generally challenging the male dominance associated with literary activity in the sixties.