Chapter: I Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rock Arts of Buddhist Caves in Vidarbha (Maharashtra) India

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 3 (2021)pp: 01-09 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Rock Arts of Buddhist Caves in Vidarbha (Maharashtra) India Dr Akash Daulatrao Gedam Asst. Prof. Dept. Applied Sciences & Humanities, Yeshwantrao Chavan College of Engineering, Wanadongari, Hingna Road, Nagpur-441110 Received 02 Mar, 2021; Revised: 12 Mar, 2021; Accepted 14 Mar, 2021 © The author(s) 2021. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org I. INTRODUCTION: Vidarbha (19° 21”N and long 76° 80”E) is an eastern part of Maharashtra state and is outside the Deccan trap area and falls geologically in the Gondwana formation. It is border the state of Madhya Pradesh to the north, Chhattisgarh in the east, Telangana in the south and Marathwada and Khandesh regions of Maharashtra in the west. Situated in central India, Vidarbha has its own rich, cultural and historical background distinct from rest of Maharashtra, Besides in archaeological remains. Nagpur having Archaeological evidence at every part, the Prehistory Branch of the Archaeological Survey of India, Nagpur has reported Middle Palaeolithic and Upper Palaeolithic sites from the district (IAR 2002-03: 145-148). A notable discovery was of a Neolithic celt made on schist (Adam Excavation 1987-1996) a very less countable prehistoric site in situated Vidarbha region. After that early Mauryan and Mauryan activities in this area and majority of sites are belongs to Satavahanas period. We found archaeological evidences ranging from prehistoric period to modern era at every part of Vidarbha and particularly in Nagpur, Chandrapur, Bhandara and Gondia districts which are known to archaeologist for burial of Megalithic people. -

An Archaeological Analysis of Early Buddhism and the Mauryan Empire at Lumbini, Nepal

Durham E-Theses The Mauryan Horizon: An Archaeological Analysis of Early Buddhism and the Mauryan Empire at Lumbini, Nepal TREMBLAY, JENNIFER,CARRIE How to cite: TREMBLAY, JENNIFER,CARRIE (2014) The Mauryan Horizon: An Archaeological Analysis of Early Buddhism and the Mauryan Empire at Lumbini, Nepal , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11038/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract The Mauryan Horizon: An Archaeological Analysis of early Buddhism and the Mauryan Empire at Lumbini, Nepal Jennifer Carrie Tremblay The archaeology of Buddhism in South Asia is reliant on the art historical study of monumental remains, the identification of which is tied to the textual historical sources that dominate Buddhist scholarship. The development and spread of early Buddhism from the third century BCE has been intrinsically linked with the Mauryan Emperor Asoka, and is consequently reliant on the identification of ‘Mauryan’ remains in the archaeological record. -

Water & Climate Resilience Programme (WACREP), India

India Water Partnership Water & Climate Resilience Programme (WACREP), India Report on Creating a Knowledge Platform for Advocating and Bringing about Changes in the Reservoir Operation Schedules (ROS) and Documenting Farm level/Pond level Practices Activity No. 3.6.1.A (Work Package-6) : i) Creating a knowledge platform for advocating and bringing about changes in the reservoir operation schedules (ROS) of the major dams in Wainganga, namely Sanjay Sarovar & Gosikhurd Dam ii) Documenting farm level/pond level practices which have demonstrated resilience to climate change as a reference guide used to enhance capacity, Gomukh Environmental Trust for Sustainable Development 92/2, Durga, Ganagote Path, Erandwane, Pune 411 004 Tel: + 91 20 – 25673324 / 08380003155 E-mail id - [email protected] / [email protected] India Water Partnership (IWP) Secretariat- WAPCOS Ltd. 76-C, Sector-18, Institutional Area, Gurgaon - 122015 (Haryana) Tel. : (91-0124) 2348022 (D); (91-0124) 2399421, Extn : 1404 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Web: www.cwp-india.org Facebook: India Water Partnership 1 Contents Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................................4 Background .............................................................................................................................................5 Project Area: ...........................................................................................................................................6 -

Buddhism in the Northern Deccan Under The

BUDDHISM IN THE NORTHERN DECCAN UNDER THE SATAVAHANA RULERS C a ' & C > - Z Z f /9> & by Jayadevanandasara Hettiarachchy Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the University of London 1973* ProQuest Number: 10731427 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731427 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT This study deals with the history of Buddhism in the northern Deccan during the Satavahana period. The first chapter examines the evidence relating to the first appearance of Buddhism in this area, its timing and the support by the state and different sections of the population. This is followed by a discussion of the problems surrounding the chronology of the Satavahana dynasty and evidence is advanced to support the ’shorter chronology*. In the third chapter the Buddhist monuments attributable to the Satavahana period are dated utilising the chronology of the Satavahanas provided in the second chapter. The inscriptional evidence provided by these monuments is described in detail. The fourth chapter contains an analysis and description of the sects and sub-sects which constituted the Buddhist Order. -

Integrated Development and Management Plan for Water Resources Wainganga Sub- Basin (Godavari), Maharashtra

Annual Report on IWP sponsored Project Integrated Development and Management Plan for Water Resources Wainganga Sub- Basin (Godavari), Maharashtra For the, Water Resources Department, Government of Maharashtra Prepared and Submitted by, Gomukh Environmental Trust for Sustainable Development, Pune 24th December, 2012 1 Acknowledgements: The Gomukh Environmental Trust for Sustainable Development commenced with the task of preparing an ‘Integrated Water Resource Development Plan for the Wainganga Sub- basin’. We wish to thank the Water Resources Department of Government of Maharashtra for giving us the opportunity for taking on this immense task. We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to India Water Partnership (IWP), New Delhi for providing us with the financial assistance in the initial months. This helped us to conduct our stakeholder meetings and workshops on the field. The IWP has also provided us with funds for printing the book the first part of the book on “Wainganga: Planning for Water Resource Development”. The Trust is especially indebted to Dr. D.M. More for his guidance and unstinting support. We are also thankful to our field-coordinator Mr. Manish Rajankar whose research work and field experiences proved extremely valuable in data collection and procurement of documents from various government agencies and departments. Finally, we wish to acknowledge all the elderly villages residing on the banks of Wainganga and in settlements and villages in forests who gave us intricate details and important insights about the dynamic interactions of streams, river and forests. Table of content: Acknowledgements: ............................................................................................................... 2 1. The Wainganga Shodh Yatra .............................................................................................. 5 2. West Zone Water Partnership Workshops and International Water Forums: .................. -

Archaeology of Buddhism in Vidarbha Region, Vidarbha (Maharashtra)

Archaeology of Buddhism in Vidarbha Region, Vidarbha (Maharashtra) Synopsis Submitted by: NISHANT SUNIL ZODAPE (Registration No.: VB-2013 of 2017-18) In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHY Guide Name: Dr. ANIL KUMAR DEPARTMENT OF ANCIENT INDIANHISTORY, CULTURE & ARCHEOLOGY, VISVA BHARATHI UNIVERSITY, SHANTINIKETAN BOLPUR, WEST BANGAL-731235 Archaeology of Buddhism in Vidarbha Region, Vidarbha (Maharashtra) Introduction: Vidarbha region (Lat. 19˚21’ N and 76˚80’ E) the study area of this synopsis is situated in eastern part of Maharashtra. Wardha River divided Vidarbha in two region eastern part and western part of Vidarbha. Presently in Vidarbha region eleven districts viz., Buldhana,Wardha, Akola, Washim, Amaravati, Yawatmal, Nagpur, Bhandara, Chandrapur, Gondia, and Gadchiroli. Vidarbha region divided in two region eastern part and western part. Vidarbha is in the eastern region of the Indian state of Maharashtra, comprising Nagpur Division and Amravati Division. Its former name is Berar (Varhad in Marathi). It occupies 31.6% of the total area and holds 21.3% of the total population of Maharashtra. It is border the state of Madhya Pradesh to the north, Chhattisgarh in the east, Telanganain the south and Marathwada and Khandesh regions of Maharashtra in the west. Situated in central India, Vidarbha has its own rich, cultural and historical background distinct from rest of Maharashtra. The largest city in Vidarbha is Nagpur. A majority of Vidarbha people speak Varhadi and Zadi dialects of Marathi. Vidarbha region is very rich in archaeological remains. From prehistoric time to modern times, the archaeological evidences are available in this region. -

V Comparative Study of Buddhist Art and Iconography of Western India

CHAPTER: V COMPARATIVE STUDY OF BUDDHIST ART AND ICONOGRAPHY OF WESTERN INDIA “The Sanskrit word ‘Kala,’ for the term ‘Art’, served a specific function, covering the many varieties of creative expressions, such as painting, sculpture, poetry, music, dance and architecture.”1. The relation between art and religion has been emerging hand in hand from the dim recesses of pre-history. There can be no great art, or great periods of art, without an intimate link between art and religion. Even in antiquity, man noticed that art “educates while entertaining”. They also render art its power of suggestion. The set of these issues inevitably leads the researcher up to the question of human nature, which is what determines the qualities of art. The simple word ‘art’2 is most usually associated with those arts which is distinguished as ‘plastic’ or ‘visual’, but properly speaking it should include the arts of literature and music. Indian art is an expression of Indian life and thought attuned to its vast natural background and its socio-religious traditions. It is not exclusive or sectarian in the narrow sense of the term. Its style, technique or general tenor has nothing to do with any particular religious outlook. It is fed and fostered upon a vast storehouse of Indian traditions, symbols and designs. The term Hindu, Jaina or Buddhist art is but a popular nomenclature to distinguish one group of monuments, including Sculpture, painting, cave-temples and architecture, etc., from another standpoint of the predominance of one or the other religious theme. Hence, by Buddhist art is meant popularly those monuments and paintings which have for the main purpose the edification or popularization of Buddhism. -

Bulletin of Tibetology

6th NOVEMBER. 1914 PR.INTED BY THE MANAGBIl. SIJ(KIM GOVEIlMNENT PREIS AND PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR, NAMGY AL INSTITUTE OF TIBETOLOGY GANGTOK , ' SIR TASHI NAMGYAL MEMORIAL LECTURES 1974 BUDDHIST ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN INDIA AND NEPAL By KRISHNA DEVA ARCHAEOLOGICAL ADVISER INDIAN COOPERATION MISSION KATHMANDU (NEPAL) CONTINI'S Pages I. Buddhist Art in India 5 II. Buddhist Architecture in India 12 III. Buddhist Art in Nepal 29 IV. Buddhist Architecture in Nepal 46 PREFACIL I am indeed grateful to the Chogyal of Sikkim and Dr. A.M. 0' Rozario, the Pre~ident and Director rei>pectively of the N;:mgyd lf1stAfute of Tibetology, for h<,ving invited me to deliver the 1974 Sir Tashi Namgyal Memorial Lectures. I have been a stmknt c,f Indian art and archItecture including Buddhist art during my long senice with the Archa.eologicd Survey Jt/india and have als(l <;tudied the art and architect me oj NepJ during the last ten years and more intensively during the lest two years as l\r,~haeological Ad,:i~er to His Majesty's Government of Nepal. Nepal has been open to the artistic and religious influences fl( wing from her great southern neighbour India. and her great northei n neighbour Tibet and has had tire genius to' (so catalyse these inflm ncf' that her at and culture have become truly Nepali. Sikkim h~,.s like wise ben' ( Fen to the cultur<ll, religious and artistic impacts coming fn-.m not only India and Tibet but also from Nepal and has similarly had the genius to assimilate them into her culture. -

Impact Assessment Report: Bhandara, India

1 Copyright © Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), 2015. All rights reserved. 2 Bhandara has a population of more than 1.2 million people. The main economic activity is agriculture, especially rice, industries and forest resources. 66.6% of the population has drinking water sources outside their home in Bhandara district (per India Development Indicators 2012, reported by UNICEF). Surface and subsurface water in Bhandara is polluted mainly due to fertilisers, pesticides, brassware pollutants, mining, ordinance industry pollution and their waste water discharge into the river and ground water. Multi contaminants are found in the local water sources - mainly nitrate, TDS, Fluorine and Chlorine, bivalent cations copper and zinc leading to health hazards. There are frequent episodes of water borne diseases – cholera, jaundice, and typhoid especially in the monsoon season, as sewage treatment facilities are negligible and raw sewage is discharged into the river. BHEL understands the importance of clean drinking water as fundamental to good health. With Safe Water Network, BHEL sought to improve the lives of the rural poor around its station vicinity by providing locally- owned and operated, affordable, sustainable water to communities to improve their health, generate livelihoods and most importantly enable girls to attend school. BHEL committed to set up 240 mw solar photo voltaic cells and 100 mw photo voltaic modules in Sakoli, providing employment to over 3,000 people. This report captures how the BHEL corporate social responsibility (CSR) intervention transformed the lives of the people in these villages and adjoining areas where treated water is supplied. 3 CONTEXT ........................................................................................................................................ 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................. 6 1. -

Urban Regeneration of Historic Towns: Regeneration Strategies for Pauni, India

The Sustainable City IV: Urban Regeneration and Sustainability 209 Urban regeneration of historic towns: regeneration strategies for Pauni, India P. Parlewar & Y. Fukukawa School of Architecture and Planning, Chiba University, Japan Abstract The urban regeneration of historic towns is a process of inducing life into decaying assets and developing future potential. These assets and potentials may consist of built heritage, traditional industries or cultural resources. The research is a study of an historic town in central India called Pauni which is famous for its historic buildings and traditional economic industry. However, at present these assets are degenerating due to industrialization. Between the 14th and 16th centuries, the town achieved prosperity because of location, linkages, political patronage and existing economic skills. Later the town could not achieve growth due to a lack of economic potential and out migration of skilled workers. Also the inadequate development polices affected the town’s growth and with the passage of time it retained the historic settlement pattern. The town today has a strong potential for tourism as there are numerous historic buildings. The town economy is dominated by household industry of skilled master craftsmen involved in producing fabric from silk and cotton. But at present, this traditional heritage and the economic potential of the town are struggling to survive. The research looks into the town’s assets and potentials that could be a base for development and sustainability. Keywords: historic towns, urban regeneration, urban conservation, urban planning, built heritages, household industry, handloom cottage industry, sustainability, weavers, tourism. 1 Introduction The settlement patterns in India are an overlay of civilizations belonging to different periods in the history of Hindu, Buddhist, Mughals and British rule. -

Pauni Municipal Council Water Supply Department

1 PAUNI MUNICIPAL COUNCIL WATER SUPPLY DEPARTMENT e- TENDER NOTICE NO FOR 2018-19 - Name of PAUNI WSS under NAGAROTTHAN Programme, work : Taluka PAUNI & District : BHANDARA, Approach Channel, Jack well & Over Head Pump House, RCC Approach Bridge, Raw water Rising Main, Pure Water Rising Main, Construction of Conventional WTP, RCC ESR’s, D/system, allied works and O & M of Scheme for one year etc. complete. TENDER DOCUMENTS CHIEF OFFICER PAUNI MUNICIPAL COUNCIL SAVE WATER EVERY DROP COUNTS ` Contractor No. of correction Chief Officer 2 PRESS TENDER NOTICE Contractor No. of correction Chief Officer 3 नगरपािलका इ-िनिवदा सुचना . सन 2018 पवनी पाणी पुरवठा योजना ता. पवनी, िज.भंडारा. या कामाची िनिवदा नगरपािलका पवनी कडून मागवीयात येत आहे. कामाची अंदाजीत कमत .20,27,26,944/-असून या कामासंबधीया सिवतर तपशील www.mahatenders.gov.in या वेबसाईटवर उपलध आहे. िदनांक: / /2018. सही/- मुयािधकारी ............................. Contractor No. of correction Chief Officer 4 NAGAR PARISHAD e-Tender Notice No. for 2018 Nagar Parishad PAUNI invites e-Tender for the work of PAUNI Water Supply Scheme at Tal. PAUNI & Dist. BHANDARA in the State of Maharashtra, valued at Rs. 20,27,26,944/- Please visit website www.mahatenders.gov.in for detailed information. Date:- Sd/- PAUNI Nagar Parishad Contractor No. of correction Chief Officer 5 PAUNI MUNICIPAL COUNCIL WATER SUPPLY DEPARTMENT Name of work : PAUNI WSS under NAGAROTTHAN Programme, Taluka PAUNI, District : BHANDARA, Construction of Approach Channel, Jack well & Over Head Pump House, RCC Approach Bridge, Raw water Rising Main, Pure Water Rising Main, Construction of Conventional WTP, RCC ESRs, D/system, allied works and O & M of scheme for one year etc. -

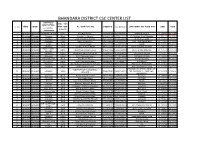

Bhandara District Csc Center List

BHANDARA DISTRICT CSC CENTER LIST ग्रामपंचायत/ झोन / वा셍ड महानगरपाललका Sr. No. जि쥍हा तालुका (फ啍त शहरी कᴂद्र चालक यांचे नाव मोबाईल क्र. CSC-ID/MOL- आपले सरकार सेवा कᴂद्राचा प配ता अ啍ांश रेखांश /नगरपररषद कᴂद्रासाठी) /नगरपंचायत 1 Bhandara Bhandara SHASTRI CHOUK Urban Amit Raju Shahare 9860965355 753215550018 SHASTRI CHOUK 21.177876 79.66254 2 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Avinash D. Admane 8208833108 317634110014 Dr. Mukharji Ward,Bhandara 21.1750113 79.65582 3 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Jyoti Wamanrao Makode 9371134345 762150550019 NEAR UCO BANK 21.174854 79.64352 4 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Sanjiv Gulab Bhure 9595324694 633079050019 CIVIL LINE BHANDARA 21.171533 79.65356 5 Bhandara Bhandara paladi Rural Gulshan Gupta 9423414199 622140700017 paladi 21.169466 79.66144 6 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban SUJEET N MATURKAR 9970770298 712332740018 RAJIV GANDHI SQUARE 21.1694655 79.66144 RAJIV GANDI 7 Bhandara Bhandara Urban Basant Shivshankar Bisen 9325277936 637272780014 RAJIV GANDI SQUARE 21.167537 79.65599 SQUARE 8 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Mohd Wasi Mohd Rafi Sheikh 8830643611 162419790010 RAJENDRA NAGAR 21.16685 79.655364) 9 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Kartik Gyaniwant Akare 9326974400 311156120014 IN FRONT OF NH6 21.166096 79.66028 10 Bhandara Bhandara Tekepar[kormbi] Rural Anita Eknath Bhure 9923719175 217736610016 Tekepar[kormbi] 21.1642922 79.65682 11 Bhandara Bhandara BHANDARA Urban Priya Pritamlal Kumbhare 9049025237 114534420013 BHANDARA 21.162895 79.64346 12 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Md. Sarfaraz Nawaz Md Shrif Sheikh 8484860484 365824810010 POHA GALI,BHANDARA 21.162768 79.65609 13 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Nitesh Natthuji Parate 9579539546 150353710012 Near Bhandara Bus Stop 21.161485 79.65576 FRIENDLY INTERNET ZONE, Z.P TARKESHWAR WASANTRAO 14 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban 9822359897 434443140013 SQ.