B/-1 SS • Piano Vicinity Kendall County Illinois I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe from Traditional Neoclassical Homes to Modernism

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe From Traditional Neoclassical Homes to Modernism AUK College of Art & Sciences/ID IND311 Interior Design History II Asst. Prof. Siniša Prvanov Spring 2019 Page 1 of 96 Contents: Introduction 1. Barcelona Pavilion 1929. 2. Villa Tugendhat 1930. 3. Farnsworth House 1946. 4. New National Gallery, Berlin 1968. 5. Furniture Design Page 2 of 96 INTRODUCTION Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (March 27, 1886 - August 17, 1969) was a German-American architect. Along with Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright, he is regarded as one of the pioneers of modernist architecture. Mies was a director of the Bauhaus, a seminal school in modern architecture. After Nazism's rise to power, and with its strong opposition to modernism (leading to the closing of the Bauhaus itself), Mies went to the United States. He accepted the position to head the architectural school at the Illinois Institute of Technology, in Chicago. Mies sought to establish a new architectural style that could represent modern times just as Classical and Gothic did for their own eras. He created a new twentieth-century architectural style, stated with extreme clarity and simplicity. His mature buildings made use of modern materials such as industrial steel and plate glass to define interior spaces. He strove toward an architecture with a minimal framework of structural order balanced against the implied freedom of unobstructed free-flowing open space. He called his buildings "skin and bones" architecture. He sought an objective approach that would guide the creative process of architectural design, but was always concerned with Page 3 of 96 expressing the spirit of the modern era. -

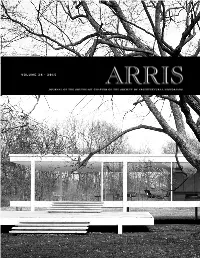

Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M

VOLUME 26 · 2015 JOURNAL OF THE SOUTHEAST CHAPTER OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS Volume 26 · 2015 1 Editors’ Note Articles 6 Madness and Method in the Junkerhaus: The Creation and Reception of a Singular Residence in Modern Germany MIKESCH MUECKE AND NATHANIEL ROBERT WALKER 22 Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency SARAH M. DRELLER 40 The “Monster Problem”: Texas Architects Try to Keep it Cool Before Air Conditioning BETSY FREDERICK-ROTHWELL 54 Electrifying Entertainment: Social and Urban Modernization through Electricity in Savannah, Georgia JESSICA ARCHER Book Reviews 66 Cathleen Cummings, Decoding a Hindu Temple: Royalty and Religion in the Iconographic Program of the Virupaksha Temple, Pattadakal REVIEWED BY DAVID EFURD 68 Reiko Hillyer, Designing Dixie: Tourism, Memory, and Urban Space in the New South REVIEWED BY BARRY L. STIEFEL 70 Luis E, Carranza and Fernando L. Lara, Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art, Technology, and Utopia REVIEWED BY RAFAEL LONGORIA Field Notes 72 Preserving and Researching Modern Architecture Outside of the Canon: A View from the Field LYDIA MATTICE BRANDT 76 About SESAH ABSTRACTS Sarah M. Dreller Curtained Walls: Architectural Photography, the Farnsworth House, and the Opaque Discourse of Transparency Abstract This paper studies the creation, circulation, and reception of two groups of photographs of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s iconic Farnsworth House, both taken by Hedrich Blessing. The first set, produced for a 1951 Architectural Forum magazine cover story, features curtains carefully arranged according to the architect’s preferences; the Museum of Modern Art commis- sioned the second set in 1985 for a major Mies retrospective exhibition specifically because the show’s influential curator, Arthur Drexler, believed the curtains obscured Mies’ so-called “glass box” design. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

B-4480 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word process, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name One Charles Center other names B-4480 2. Location street & number 100 North Charles Street Q not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP County Independent city code 510 zip code 21201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this G3 nomination • request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property C3 meets • does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally • statewide K locally. -

Flooded at the Farnsworth House MICHAEL CADWELL the Ohio State University

392 THE ART OF ARCHITECTURE/THE SCIENCE OF ARCHITECTURE Flooded at the Farnsworth House MICHAEL CADWELL The Ohio State University In 1988, nearly twenty years after his mentor’s the means by which this drama unfolded. Duckett’s death, the architect Edward A. Duckett remem- stick and his act of framing recall the central ar- bered an afternoon outing with Mies van der Rohe. chitectural activity of drawing: the stick, now a One time we were out at the Farnsworth House, pencil, describes a frame, now a building, which and Mies and several of us decided to walk down affords a particular view of the world. In this es- to the river’s edge. So we were cutting a path say, I will elaborate on the peculiar intertwining of through the weeds. I was leading and Mies was building, drawing, and nature at the Farnsworth right behind me. Right in front of me I saw a young House; how drawing erases a positivist approach possum. If you take a stick and put it under a young to building technology and how, in turn, a pro- possum’s tail, it will curl its tail around the stick found respect for the natural world deflects and, and you can hold it upside down. So I reached finally, absorbs the unifying thrust of perspective. down, picked up a branch, stuck it under this little possum’s tail and it caught onto it and I turned Approached by Dr. Farnsworth in the winter of around and showed it to Mies. Now, this animal is 1946/7 to design a weekend house, Mies responded thought by many to be one of the world’s ugliest, with uncharacteristic alacrity. -

Forumjournal VOL

ForumJournal VOL. 32, NO. 3 Heritage in the Landscape Contents NATIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION VOL. 32, NO. 3 PAUL EDMONDSON President & CEO Cultural Landscapes and the National Register KATHERINE MALONE-FRANCE BARBARA WYATT ...............................................3 Chief Preservation Officer TABITHA ALMQUIST Chief Administrative Officer Large-Landscape Conservation: A New Frontier THOMPSON M. MAYES for Cultural Heritage Chief Legal Officer & BRENDA BARRETT ............................................. 13 General Counsel PATRICIA WOODWORTH Honoring and Preserving Hawaiian Cultural Interim Chief Financial Officer Landscapes GEOFF HANDY Chief Marketing Officer BY DAVIANNA PŌMAIKA‘I MCGREGOR .............................22 PRESERVATION Stewarding and Activating the Landscape LEADERSHIP FORUM of the Farnsworth House SUSAN WEST MONTGOMERY SCOTT MEHAFFEY. .30 Vice President, Preservation Resources Tribal Heritage at the Grand Canyon: RHONDA SINCAVAGE Director, Publications and Protecting a Large Ethnographic Landscape Programs to Sustain Living Traditions SANDI BURTSEVA BRIAN R. TURNER .............................................. 41 Content Manager KERRI RUBMAN Assistant Editor Meshing Conservation and Preservation Goals PRIYA CHHAYA with the National Register Associate Director, ELIZABETH DURFEE HENGEN AND JENNIFER GOODMAN .............50 Publications and Programs MARY BUTLER Adapting to Maintain a Timeless Garden at Filoli Creative Director KARA NEWPORT . 61 Cover: Beach Ridges on the Shore of Cape Krusenstern, part of Cape Krusenstern National Monument in Alaska PHOTO COURTESY OF NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Forum Journal, a publication of the National Trust for Historic Preservation (ISSN 1536-1012), is published by the Preservation Resources Department at the National Trust for Historic Preservation, 2600 Virginia Avenue, NW, Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20037 as a benefit of National Trust Forum The National Trust for Historic Preservation works to save America’s historic places for membership. -

Oscarsaysknoll

There are the film stars of the world: Grace Kelly, Marilyn Monroe, Bridget Bardot, Meryl Streep. Such talent and beauty. But we’re more interested in the talent behind furniture beauties: Saarinen and Bertoia and van der Rohe. Knoll designs have featured prolifically in film, from the classical to the contemporary to the futuristic - evidence that Knoll is Modern Always. Whether it’s a Bertoia Chair in Devil Wears Prada or a Platner Chair in Quantum of Solace, furniture can often hijack the attention of the audience, away from the action and dialogue of a film to communicate values and mood wordlessly. A well-chosen sofa, chair, or table can subliminally tell us more about a character’s personality or an environment’s tone than many pages of script. When a production designer needs to convey a character’s good taste and discerning style or when they simply need an extremely handsome piece in a domestic or office setting, we’ll often spot a Knoll. With the Oscars upon us, allow us to recognize some of our most prominent leading characters to grace the big screen. EERO SAAR INEN THE WOMB CHAIR was a groundbreaking design by Saarinen at Florence Knoll's request for "a chair that was like a basket full of pillows - something she could really curl up in." This mid-century classic supportas countless positions and offers a comforting oasis of calm—hence the name. And resulting in being staged on countless sets for a sense of chic comfort and style. THE WOMB CHAIR IN LEGALLY BLONDE “Endorphins make you happy…” and so does good design. -

List of Illinois Recordations Under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (As of April 2021)

List of Illinois Recordations under HABS, HAER, HALS, HIBS, and HIER (as of April 2021) HABS = Historic American Buildings Survey HAER = Historic American Engineering Record HALS = Historic American Landscapes Survey HIBS = Historic Illinois Building Survey (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Buildings Survey) HIER = Historic Illinois Engineering Record (also denotes the former Illinois Historic American Engineering Record) Adams County • Fall Creek Station vicinity, Fall Creek Bridge (HABS IL-267) • Meyer, Lock & Dam 20 Service Bridge Extension Removal (HIER) • Payson, Congregational Church, Park Drive & State Route 96 (HABS IL-265) • Payson, Congregational Church Parsonage (HABS IL-266) • Quincy, Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, Freight Office, Second & Broadway Streets (HAER IL-10) • Quincy, Ernest M. Wood Office and Studio, 126 North Eighth Street (HABS IL-339) • Quincy, Governor John Wood House, 425 South Twelfth Street (HABS IL-188) • Quincy, Illinois Soldiers and Sailors’ Home (Illinois Veterans’ Home) (HIBS A-2012-1) • Quincy, Knoyer Farmhouse (HABS IL-246) • Quincy, Quincy Civic Center/Blocks 28 & 39 (HIBS A-1991-1) • Quincy, Quincy College, Francis Hall, 1800 College Avenue (HABS IL-1181) • Quincy, Quincy National Cemetery, Thirty-sixth and Maine Streets (HALS IL-5) • Quincy, St. Mary Hospital, 1415 Broadway (HIBS A-2017-1) • Quincy, Upper Mississippi River 9-Foot Channel Project, Lock & Dam No. 21 (HAER IL-30) • Quincy, Villa Kathrine, 532 Gardner Expressway (HABS IL-338) • Quincy, Washington Park (buildings), Maine, Fourth, Hampshire, & Fifth Streets (HABS IL-1122) Alexander County • Cairo, Cairo Bridge, spanning Ohio River (HAER IL-36) • Cairo, Peter T. Langan House (HABS IL-218) • Cairo, Store Building, 509 Commercial Avenue (HABS IL-25-21) • Fayville, Keating House, U.S. -

Christ's College Cambridge

CHRIST'S COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE CATALOGUE OF POST-MEDIEVAL MANUSCRIPTS AND PAPERS Last updated 07/12/2017 1 CONTENTS MS. No. ITEM 1. Fragments found during the restoration of the Master's Lodge + Bible Box. 2. Fragments and photocopies of music. 3. Letter from Robert Hardy to his son Samuel. 4. Photocopies of the title pages and dedications of ‘A Digest or Harmonie...’ W.Perkins. 5. Facsimile of the handwriting of Lady Margaret (framed in Bodley Library) 6. MSS of ‘The Foundation of the University of Cambridge’ 1620 John Scott 7. Extract from the College “Admission Book” showing the entry of John Milton (facsimile) 8. Milton autographs: three original documents 9. Letter from Mrs. R. Gurney 10. Letter from Henry Ellis to Thomas G. Cullum 11. Facsimile of the MS of Milton's Minor Poems 12. Thomas Hollis & Milton 13. Notes on Early Editions of Paradise Lost by C. Lofft 14. Copy of a letter from W. W. Torrington 15. Milton Tercentenary: Visitors' Book 16. Milton Tercentenary: miscellaneous material, (including "scrapbook") 17. Milton Tercentenary: miscellaneous documents 18. MS of a 17th. century sermon by Alsop? 19. Receipt for a contribution by Sir Justinian Isham signed by M. Honywood 20. MS of ‘Some Account of Dr. More's Works’ by Richard Ward 21. Letters addressed to Dr. More and Dr. Ward (inter al.) 22. Historical tracts: 17th. century Italian MS 23. List of MSS in an unidentified hand 24. Three letters from Dr. John Covel to John Roades 25. MS copy of works by Prof. Nicolas Saunderson + article on N.S. 26. -

Detroit Modern Lafayette/Elmwood Park Tour

Detroit Modern Lafayette/Elmwood Park Tour DETROIT MODERN Lafayette Park/Elmwood Park Biking Tour Tour begins at the Gratiot Avenue entrance to the Dequindre Cut and ends with a ride heading north on the Dequindre Cut from East Lafayette Street. Conceived in 1946 as the Gratiot Redevelopment Project, Lafayette Park was Detroit’s first residential urban renewal project. The nation’s pioneering effort under the Housing Act of 1949; it was the first phase of a larger housing redevelopment plan for Detroit. Construction began at the 129-acre site in 1956. The site plan for Lafayette Park was developed through a collabora- tive effort among Herbert Greenwald, developer; Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, architect; Ludwig Hilberseimer, city planner; and Alfred Caldwell, landscape architect. Greenwald had a vision of creating a modern urban neighborhood with the amenities of a suburb. Bounded by East Lafayette, Rivard, Antietam and Orleans Streets, Lafayette Park is based on the ‘super- block’ plan that Mies van der Rohe and Hilberseimer devised in the mid-1950s. The 13-acre, city-owned park is surrounded by eight separate housing components, a school and a shopping center. Mies van de Rohe designed the high-rise Pavilion Apartment buildings, the twin Lafayette Towers, and the low-rise townhouses and court houses in the International style for which he is famous. They are his only works in Michigan and the largest collection of Mies van de Rohe-designed residential buildings in the world. Caldwell’s Prairie style landscape uses native trees, curving pathways, and spacious meadows to create natural looking landscapes that contrast with the simplicity of the buildings and the density of the city. -

Rosse Papers Summary List: 17Th Century Correspondence

ROSSE PAPERS SUMMARY LIST: 17TH CENTURY CORRESPONDENCE A/ DATE DESCRIPTION 1-26 1595-1699: 17th-century letters and papers of the two branches of the 1871 Parsons family, the Parsonses of Bellamont, Co. Dublin, Viscounts Rosse, and the Parsonses of Parsonstown, alias Birr, King’s County. [N.B. The whole of this section is kept in the right-hand cupboard of the Muniment Room in Birr Castle. It has been microfilmed by the Carroll Institute, Carroll House, 2-6 Catherine Place, London SW1E 6HF. A copy of the microfilm is available in the Muniment Room at Birr Castle and in PRONI.] 1 1595-1699 Large folio volume containing c.125 very miscellaneous documents, amateurishly but sensibly attached to its pages, and referred to in other sub-sections of Section A as ‘MSS ii’. This volume is described in R. J. Hayes, Manuscript Sources for the History of Irish Civilisation, as ‘A volume of documents relating to the Parsons family of Birr, Earls of Rosse, and lands in Offaly and property in Birr, 1595-1699’, and has been microfilmed by the National Library of Ireland (n.526: p. 799). It includes letters of c.1640 from Rev. Richard Heaton, the early and important Irish botanist. 2 1595-1699 Late 19th-century, and not quite complete, table of contents to A/1 (‘MSS ii’) [in the handwriting of the 5th Earl of Rosse (d. 1918)], and including the following entries: ‘1. 1595. Elizabeth Regina, grant to Richard Hardinge (copia). ... 7. 1629. Agreement of sale from Samuel Smith of Birr to Lady Anne Parsons, relict of Sir Laurence Parsons, of cattle, “especially the cows of English breed”. -

Farnsworth House™ Plano, Illinois, USA

Farnsworth House™ Plano, Illinois, USA Booklet available on: Das Heft ist verfügbar auf: Livret disponible sur: Folleto disponible en: Folheto disponível em: A füzet elérhető: Architecture.LEGO.com 21009_.indd 1 02/03/2011 12:22 PM Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, born Maria Ludwig Michael Mies (March 27, 1886 – August 17, 1969) was an architect and designer. Mies has long been considered one of the most important architects of the 20th century. In Europe, before World War II, Mies emerged as one of the most innovative leaders of the Modern Movement, producing visionary projects and executing a number of small but critically significant buildings. After emigrating to the United States in 1938, he transformed the architectonic expression of the steel frame in American architecture and left a nearly unmatched legacy of teaching and building. Born in Aachen, Germany, Mies began his architectural career as an apprentice at the studio of Peter Behrens from 1908 to 1912. There he was exposed to progressive German culture, working alongside Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier. Determined to establish a new architectural style that could represent modern times just as Classical and Gothic had done for their own eras, Mies began to develop projects that, though most remained unbuilt, rocketed him to fame as a progressive architect. His dramatic modernist debut was his stunning competition proposal for the all-glass Friedricstrasse skyscraper in 1921. He continued with a whole series of pioneering projects, including the temporary German Pavilion for the Barcelona exposition (often called the Barcelona Pavilion) in 1929. -

Mies Van Der Rohe Collection Florence Knoll Collection Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe Collection

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Collection Florence Knoll Collection Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Collection From his work on the German Pavilion in Barcelona to the Tugendhat House in Brno, the Seagram Building in New York to the Farnsworth House in Illinois, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe defined an architectural vocabulary for the modern world in terms that are clear and honest. For his famous 1929 German Pavilion, Mies designed the classic Barcelona® chair and ottoman. Subsequently, in 1930, he created the Brno and MR Collections for the Tugendhat House in Brno, Czechoslovakia. These pieces mirror the groundbreaking simplicity of their original environments, with simple profiles, clean lines and meticulous attention to detail. They demonstrate the Bauhaus approach to combining industrial materials and modern forms. In 2004, KnollStudio introduced the Krefeld™ Collection, designed by Mies in 1927 for a residence in Krefeld, Germany, but never produced. Developed in collaboration with The Museum of Modern Art, the Krefeld Collection offers beautifully proportioned pieces that reflect Mies’ fondness of traditional furniture types. After emigrating to the United States in 1937, Mies formed a lasting friendship with a young student, Florence Knoll, who in 1948 acquired exclusive rights to produce the Barcelona Collection. Knoll subsequently acquired the remainder of Mies’ furniture designs, pieces that have taken their place among the most profoundly original furniture designs of the twentieth century. One day, Florence Knoll and Gordon Bunshaft, a leading partner in the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, were leaving the office of a large commercial client. “Where would they be without us?” she jokingly asked.