At Journalism's Boundaries: a Reporter's Journey From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The News-Sentinel 1959

The News-Sentinel 1959 Friday, January 2, 1959 Oliver H. Heckaman Oliver E. HECKAMAN, 73, R.R. 3, Argos, died at 1:40 p.m. Thursday at Parkview hospital, Plymouth, where he had been a patient since suffering a heart attack six days earlier. Mr. Heckaman, a farmer who had spent his entire life in Marshall county was born near Bremen, Oct. 3, 1885, the son of Samuel and Saraj BROCKER HECKAMAN. He had lived in Bremen, LaPaz and Argos. He was first married in 1904 to Chloe B. JONES, who died in 1944. In 1946 Mr. Heckaman was maried to Lois SWOVERLAND, who survives. Other survivors include three daughers, Mrs. Frank (Inez) THOMAS, LaPaz, and Mrs. Roger (Hope) WINTERS and Mrs. Glenn (Mary) STAFFORD, both of Portland, Ore.; four sons, William [HECKAMAN], Portland, Ore.; Herbert and David [HECKAMAN] of Lakeville and Oliver [HECKAMAN], Jr., Plymouth; fourteen grandchildren; eight great-grandchildren; three step-daughters, Mrs. Betty MAST, Nappanee, Mrs. Meril (Dorothy) OVERMYER, Plymouth, and Miss Margaret SWOVERLAND, at home; a stepson, Donald SWOVERLAND, at home; two step-grandchildren; a sister, Mrs. Ralph HUFF, Bremen, and two brothers, Monroe [HECKAMAN], Etna Green, and Charles [HECKAMAN], Beech, N.D. Services will be conducted at 2 p.m. Sunday by the Rev. Lester CLEVELAND of the Santa Anna Methodist church at the Grossman funeral home, Argos, where friends may call after 7 p.m. today. Burial will be in New Oak Hill cemetery, Plymouth. Martha V. Atkinson Fulton county’s 1959 traffic toll leaped to one killed and at least six injured Thursday, before the New Year was even a day old. -

And Gold 80 Years Ago

HIGHLIGHTS Welcome from our AAAA President ............. 3 AA Superintendent ..................................... 4 The Blue AA High School Principal ........................... 5 AA Elementary Principal ........................... 5 and Gold 80 years ago ............................................... 6 Past Yearbook Dedications ....................... 9 Outstanding Service Award ...................... 11 2019 Sports Hall of Fame Inductees ................. 12 Alfred Almond Central School Spotlight on Alumni ................................... 16 Alumni Newsletter Scholarships Class of 2018 ..................... 20 Summer Campers say Thank You ............ 23 Reunion News ........................................... 24 Alumni News .............................................. 29 Dues Payers .............................................. 33 Donations ................................................... 36 ALMOND--- More than 260 Alfred-Almond Central School alumni gathered at Alfred Memorials ................................................... 42 State’s Central Dining Hall on July 21 for their 58th annual alumni banquet. The theme, Condolences ............................................. 45 “A Blue and Gold Christmas in July” was carried out in the room décor, printed pro- Notice of Annual Membership meeting ..... 46 grams and table decorations. RSVP/Reservation Form ........................... 49 Special guests for the event were the 2018 scholarship winners, who received $40,000 in awards presented by AAAA President Lisa Patrick, -

Tarboro High School Yearbook, Tar-Hi Tattler, 1944

Tayc^^ ^^^L ^scAcr^ - y SENIOR ISSUE Published by THE CLASS OF 1944 TARBORO HIGH SCHOOL TARBORO, N. C. D EDICATION For her infinite patience and sympathetic guidance through our early formative years, and in love We the Class of 19H, gratefully dedicate to Mrs. A. D. Mizell, together with Mrs. Martha Spiers, who has been the source of deep wisdom, unswerving loyalty, sweet fellowship, and ideal Christian leadership, this senior issue of The Tar-Hi Tattler FACULTY Sitting (Left to Right) Miss Mary Pool Commercial Miss Dorothaleen Hales French, English Mrs. Luther Cromartie English Miss Louise Bryan History, Civics, Physical Education Miss Hortense Boomer Librarian Miss Ruby Langford Mathematics Standing (Left to Right) Mrs. Martha Spiers Science Mr. W. A. Mahler Superintendent Mr. Hal Bradley History, Physical Education Mr. M. M. Wetzel . .Principal, Mathematics Mrs. T. E. Belk Secretary Not in Picture Miss Josephine Grant Home Economics Miss Doris Kimel Music f9W Edwards Stott Pittman Piland Pollard Boomer Darrow Cherry Shugar Johnson Gaines STAFF Farmer Cullom (Insert) Editor-in-Chief Edwin Cherry Associate Editor Edna Edwards Statistician Jean Darrow Statistician Evelyn Shugar Advertising Manager Kate Johnson Historian Sue Gaines Advertising Manager Ralph Piland Sports Editor Charles Stott Photography Editor Frances Pollard Prophet Curtis Pittman Lawyer Allene Long Circulation Manager Miss Boomer Advisor OFFICERS President Ralph Piland Seeretary Irene Wood Vice President Charles Stott Treasurer Sue Gaines CLASS ROLL Kate Johnson, Charles -

CRANFORD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 1964 Crmford, HL 3

"i, J r Washington's Birthday Sales Today, Friday* Saturday •r '' \ Beobnd ,C1«BS" Poitajre Paid Vol. LXX. No: 5. 4 Sections, 28 Pages CRANFORD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 1964 Crmford, HL 3. TEN CENTS Gift of $100,000 to Make UJC Campus SiteBoard to Resubmit Budget on Tuesday; Of William M. Sperry Memorial Observatory The William Miller Sperry Cut $145,000 From Capital Outlay Memorial Observatory will be The Board of Education will the Lincoln School heating, $156,473 lower, made possible cational services In 1962-63 to established on the IJnion resubmit its 1964-65 budget to plant and system,. by the capital outlay cut and socially and emotionally mal- Junior College campus with a the yoters on Tuesday with a No change was made in the the news last week that the adjusted students. gift of $100,000 'from Mrs. cut of $14g,00Q in the capital current expens'e appropriation, state will reimburse $11,473 Frederick W. Beiriecke of New Voters will be asked to ap- outlay expenditure to replace but the-total .budget will be to the school system for its edu- prove an expenditure of York (Uy and William S Bei- $2,807;404 in taxes for current neckc' of Summit, it waS art- expenses and $49,600 for capi- noun'^d today by Dr. Kenneth C. Mac Kay, UJC president, tal outlay, a total of $2,857,- 1 Municipal Pool Committee Aim 004. PoMs Will, be open from"' ftn<: Hi '- Thomas Roy Jones, chair- nrj.M! 1/ the board of trustees. 2' to. -

The Hornet, 1923 - 2006 - Link Page Previous Volume 39, Issue 17 Next Volume 39, Issue 19

S1111 , 1,,,11)( 11(( t 11,11111111,,, 1 1/11))1 <". :" :y ~ .~ Basketball After Game Game- 8 P.M. SDance Tonight Tonight Student Center - _.~11)1)) ~111,1,1,111 111111 1111111(11 11 g 7e Oeca oullertonJaisia ia ebet euc1, Ndoee Vol. XXXIX Fullerton, California, Friday, February 10, 1961 No. 18 'Come Back!' Commission Posts Are Open To Applicants Presently there are three va- taking 12 units. cancies in the Fullerton Junior The AMS President's main job College Student Commission. They this semester will be to plan the are Commissioner of Rallies, As- third annual Men of Distinction sociated Men Students President wards Banquet. Each year the and Freshman Commissioner at AMS chooses the top 25 men in Large. school from every department, The office of Commissioner of such as outstanding student in Rallies is open to any FJC stu- life science, physical s c i e n ce,. dent registered in 121/2 units with humanities division, athletic div- a grade point average of 2.0. Com- sion. missioner of Rallies' main job is No experience is necessary for to direct the activities of the song this office, but it might be help- and yell leaders and to work with ful. them to promote school spirit. He The Freshman Commissioner at must also plan and conduct the Large office is open to .any fresh- tryouts for next year's song lead- man. His main job is to repre- ers and yell leaders. These posts sent the freshman class on the are open to any high school sen- student commission. -

A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996) Taylor University

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University The aT ylor Magazine Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections Spring 1996 Taylor: A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996) Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "Taylor: A Magazine for Taylor University Alumni and Friends (Spring 1996)" (1996). The Taylor Magazine. 91. https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines/91 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aT ylor Magazine by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Keeping up with technology on the World Wide Web • The continuing influence ofSamuel Morris • Honor Roll ofDonors - 1995 A MAGAZINE FOR TAYLOR UNIVERSITY ALUMNI AND FRIENDS 1846*1996 SPRING 1996 PRECIS his issue of tlie Taylor Magazine is devoted to the first 50 years of Taylor's existence. Interestingly, I have just finished T reading The Year of Decision - 1846 by Bernard DeVoto. The coincidence is in some ways intentional because a Taylor schoolmate of mine from the 1950's, Dale Murphy, half jokingly recommended that I read the book as I was going to be making so many speeches during our sesquicentennial celebration. As a kind of hobby, I have over the years taken special notice of events concurrent with the college's founding in 1846. The opera Carman was first performed that year and in Germany a man named Bayer discovered the value of the world's most universal drug, aspirin. -

Owning and Belonging: Southern Literature and the Environment, 1903 – 1979

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University OWNING AND BELONGING: SOUTHERN LITERATURE AND THE ENVIRONMENT, 1903 – 1979 A Dissertation by MICHAEL J. BEILFUSS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2012 Major Subject: English Owning and Belonging: Southern Literature and the Environment, 1903 – 1979 Copyright 2012 Michael J. Beilfuss OWNING AND BELONGING: SOUTHERN LITERATURE AND THE ENVIRONMENT, 1903 – 1979 A Dissertation by MICHAEL J. BEILFUSS Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, M. Jimmie Killingsworth Committee Members, William Bedford Clark Dennis Berthold Tarla Rai Peterson Head of Department, Nancy Warren August 2012 Major Subject: English iii ABSTRACT Owning and Belonging: Southern Literature and the Environment, 1903 – 1979. (August 2012) Michael J. Beilfuss, B.A., SUNY New Paltz; M.A., SUNY New Paltz Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. M. Jimmie Killingsworth This dissertation engages a number of currents of environmental criticism and rhetoric in an analysis of the poetry, fiction, and non-fiction of the southeastern United States. I examine conceptions of genitive relationships with the environment as portrayed in the work of diverse writers, primarily William Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren, W.E.B. Du Bois, Zora Neal Hurston, and Elizabeth Madox Roberts. Southern literature is rarely addressed in ecocritical studies, and to date no work offers an intensive and focused examination of the rhetoric employed in conceptions of environmental ownership. -

Taylor Magazine (December 1992) Taylor University

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University The aT ylor Magazine Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections 12-1992 Taylor Magazine (December 1992) Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "Taylor Magazine (December 1992)" (1992). The Taylor Magazine. 163. https://pillars.taylor.edu/tu_magazines/163 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Ringenberg Archives & Special Collections at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aT ylor Magazine by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MAGAZINE FOR TAYLOR UNIVERSITY A L U M NHkN D FRIENDS N ON PRECIS 7W ime Museum reads the small, brown, ing the death of each hour and serving as a highway information sign at Interstate-90's reminder of the brevity of life. Rockford, 111., exit. I've often passed it en "What potent symbolism" I thought. Modem route to visit family in Minnesota, but I'd clocks and watches may sport cartoon mice, fancy never stopped at the museum until this fall. graphics, or LCD displays; ne\ertheless. there is a And even then, I called ahead to ask if it would skeleton hidden in each one. Whether or not we are be worth my while. "We're putting together a hourly conscious of it. time does march on; life is magazine on the subject of time," I said. "Would it brief Our view of time affects our use of it. -

H M U Sb FIRST Castillo Arjaas Murdered Guat Ala by Soldier

PAGE FOURTEEN FRIDAY, JULY 26, iHanrbi?at)?r In^tting Hrralb Arenge Dally Net Preas Run For the Week. Ended The Weather \ Forseasf of V. 8. Wsntlwr Bursen Membera of the Mancheater Fire June 8. 1M7 Depaitment will meet at the fire Many from Town About Town headquarter^,' Main at Hilliard St., Tonight, scattered slidwers Uie tomorrow at 5 p.m.. in uniform, to Get Brae Marr 1 2 ,5 4 d \ low as to 70. Sunday, w arn n*d Edwin Rdchard, aon of Mr. and participate in the parade at Farm Member of the Audit humid srith acattered abowers. Mrs. T. Walter Reichard. 149 E. ington. Camper Awards j Bureau of Otrculatlon High In the upper 86'a. Middle Tpke., and Robert E. Rich- Manchester— A City o f Village Charm ardaon, aon <rf Mr. and Mra. Rob Membe'ra of Anderaon-Shea Poat. Saturday Is The Last Day OF Hale’s Great July ert E. Richardaon Sr., 203 High No. 2046. VFW Auxiliary, are re- Many Manchester campers Were | land St., were naihed to the dean'a quBated to meet tomgiit at .7 o'clock the recipients of awards for ouC- j VOL. LXXVL'NO. 253 (TEN PAGES) liat for the paat year at Trinity at the Holmea Funeral Home to standing achievement given recent-! MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, JULY 27. 1957 (Olnaain^Advertising on Pngs S) PRICE FIVE CENTS College. Both graduated from (he exemplify the ritual for Mra. Mary ly at a campfire ceremony at Brae : college In June. Cole, a member. Marr Day Camp, in Bolton. -

Billy Corganls

PAWSAnnual Report CHICAGOmagazine Summer 2014 SMASHING PUMPKINS FRONTMAN BILLY CORGAN’S PAWS CHICAGO ALUMNI SAMMI & MR. THOM GETTING WISER GOLD STAR DOGS ABOUTT GET ING OLDER Behavior Enrichment in TIPS FOR GERIATRIC PET CARE the No Kill model pawschicago.org IN 013 2 ABOUT If we could, we’d give it a thumbs up. 5,872 ADOPTIONS 17,767 SPAY/NEUTER SURGERIES A DOPTION VACCINATIONS, MICROCHIPS PAWS Chicago has revolutionized the shelter of Chicago’s homeless animals through its cageless, No Kill Adoption Centers in Lincoln Park and the North Shore. These Centers, in & BLOOD TESTS tandem with innovative adoption events and enrichment programs, enable PAWS Chicago to find new homes for thousands of animals each year. 39,043/YEAR OR HO LISTIC ANIMAL HEALTH & WELL-BEING 110/DAY As a No Kill shelter, PAWS Chicago is a safe haven for animals. Through a state-of-the-art Shelter Medicine program, each rescue receives full medical treatment, regardless of its condition, while a comprehensive Animal Behavior program provides social and behavioral enrichment. Each pet is treated as an individual, ensuring that he or she receives the nurturing care, treatment and rehabilitation it needs to live a healthy, happy life. SP AY/NEUTER PAWS Chicago’s Lurie Clinic - the city’s largest provider of free and low-cost spay/neuter 51,250 surgeries - and its mobile extension, the GusMobile Spay/Neuter Van, work tirelessly to bring its life-saving services to neighborhoods challenged with pet overpopulation. POUNDS OF In 2013 alone, nearly 18,000 dogs and cats were spayed or neutered through these two PET FOOD PAWS Chicago programs. -

HERALD Scheduled Tuesday

II Section one pages' HERALD ei'ght pages Puhlllll"'d C\ •• ,-!" Thuntda;. m'l.1"d "· .. (l!w"dlt~·. at 110 "lain. \\~ft~·nf·. :\,·!.r NUMBER FORTY-$EVE~ !ieadn Scheduled Tuesday G.ood Friday Union Services I Begin at Noon at local Church At left 1'5 tile Rev. O. B. Proett. pastor of the Presbyterian church in Wayne and author of thIS ye~r's Easter message. Rev. Proctt has been in Wayne since 1943 when he came here fFom Gre~ham. hlsfirst church a"S ordame-J'minister. He was a stu dent pastor at Glenvil and Colon. The Wayne pastor received i'l"1 A.B. degree from Hastings f',,) I lege, his bachelor of theology Several youngsters have been from the Presbyterian seminal'Y, celusmq disturbance recently in Omaha. and docto'll' degree from GreenwooJ cemetery, using it as Hastings college. a t.lrget area for their rifles, No "'"c h;}s been served this week by Offices he holds include stated the cemetery offiCials that "any clerk and treasurer of I\:iobrara one caugnt shootinq fircarms in Prcsbytery and stated clerk and the cemetery will be subject to treasurer -of Synod of Nebraska, flnc," Rev, and Mrs, Proett live at the Presbyterian manse at 214 West Th'lrd street, Thev are the p;ncnts of SIX childrC:l, Six Leave o ",II, It" For Service Parti'cipates Trw P,n_".,~ler l1On1(' <Inri )WU'-C'- Sl\. V\'a.\l1e county youths left !lOld g""<lrl.~ Clle' he'lnL; "old Ht pub- \\'Cl\lle b) bus Tue~day morning C A-Bomb lt~ dU( tHIn ~aturdd} 10r. -

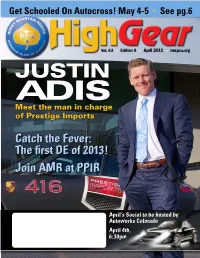

April 2013 L Rmr.Pca.Org JUSTIN ADIS Meet the Man in Charge of Prestige Imports

• Get Schooled On Autocross! May 4-5 See pg.6 Vol. 63 l Edition 8 l April 2013 l rmr.pca.org JUSTIN ADIS Meet the man in charge of Prestige Imports Catch the Fever: The first DE of 2013! Join AMR at PPIR April’s Social to be hosted by Autoworks Colorado April 4th, 6:30pm HighGear cover photo Vol. 63 Edition 8 • April 2013 presidential thoughts Rick Gonçalves, President I think we have option! turned the corner and Or, you can buy your car and take Spring is really here! Tourist Delivery in Germany, then drive You know what that as fast as you want or as fast as the car means? Track time! will go, where there is no speed limit on We need to dust off the Autobahn. Contrary to popular belief, our cars, unplug the not all the Autobahns are speed limitless, trickle chargers, do that procrastinated oil but enough still are. I can tell you, first change, and otherwise get the cars ready hand, what a thrill it is to be cruising down Justin Adis, General Manager of Prestige Imports, for the driving season, the first driving the Autobahn for hours at a time at 140 pauses for a photograph in front of his company’s GT3. event of the year being Speed Fever IV out mph with the car so stable that it feels Photo by Max Gerson. at High Plains Raceway! no different from going sixty! Obviously, Now, for those who are relatively however, not everyone can afford to buy new to the club, you should know that a new car or travel to Germany.