Americanensemble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices Valid Until Friday 25 October 2019 Unless Stated Otherwise

September 2019 Catalogue Issue 41 Prices valid until Friday 25 October 2019 unless stated otherwise ‘The lover with the rose in his hand’ from Le Roman de la 0115 982 7500 Rose (French School, c.1480), used as the cover for The Orlando Consort’s new recording of music by Machaut, entitled ‘The single rose’ (Hyperion CDA 68277). [email protected] Your Account Number: {MM:Account Number} {MM:Postcode} {MM:Address5} {MM:Address4} {MM:Address3} {MM:Address2} {MM:Address1} {MM:Name} 1 Welcome! Dear Customer, As summer gives way to autumn (for those of us in the northern hemisphere at least), the record labels start rolling out their big guns in the run-up to the festive season. This year is no exception, with some notable high-profile issues: the complete Tchaikovsky Project from the Czech Philharmonic under Semyon Bychkov, and Richard Strauss tone poems from Chailly in Lucerne (both on Decca); the Beethoven Piano Concertos from Jan Lisiecki, and Mozart Piano Trios from Barenboim (both on DG). The independent labels, too, have some particularly strong releases this month, with Chandos discs including Bartók's Bluebeard’s Castle from Edward Gardner in Bergen, and the keenly awaited second volume of British tone poems under Rumon Gamba. Meanwhile Hyperion bring out another volume (no.79!) of their Romantic Piano Concerto series, more Machaut from the wonderful Orlando Consort (see our cover picture), and Brahms songs from soprano Harriet Burns. Another Hyperion Brahms release features as our 'Disc of the Month': the Violin Sonatas in a superb new recording from star team Alina Ibragimova and Cédric Tiberghien (see below). -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

59Th Annual Critics Poll

Paul Maria Abbey Lincoln Rudresh Ambrose Schneider Chambers Akinmusire Hall of Fame Poll Winners Paul Motian Craig Taborn Mahanthappa 66 Album Picks £3.50 £3.50 .K. U 59th Annual Critics Poll Critics Annual 59th The Critics’ Pick Critics’ The Artist, Jazz for Album Jazz and Piano UGUST 2011 MORAN Jason DOWNBEAT.COM A DOWNBEAT 59TH ANNUAL CRITICS POLL // ABBEY LINCOLN // PAUL CHAMBERS // JASON MORAN // AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE AU G U S T 2011 AUGUST 2011 VOLUme 78 – NUMBER 8 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

2015/16 Season Preview and Appeal

2015/16 SEASON PREVIEW AND APPEAL SEASON PREVIEW 2015/16 01 THANK YOU WELCOME THE WIGMORE HALL TRUST WOULD LIKE TO ACKNOWLEDGE AND THANK THE FOLLOWING INDIVIDUALS AND ORGANISATIONS FOR THEIR GENEROUS SUPPORT THROUGHOUT THE 2014/15 SEASON: HONORARY PATRONS DONORS AND SPONSORS Audiences and artists have been coming together at Wigmore Hall for Aubrey Adams Mr Eric Abraham* Charles Green Rothschild André and Rosalie Hoffmann Neville and Nicola Abraham Barbara and Michael Gwinnell Ruth Rothbarth* nearly 115 years. In its intimate and welcoming environment, enthralling Sir Ralph Kohn FRS and Lady Kohn Elaine Adair Mr and Mrs Rex Harbour* The Rubinstein Circle performances of supreme musical works are experienced with a unique Mr and Mrs Paul Morgan Tony and Marion Allen* Haringey Music Service The Sainer Charity The Andor Charitable Trust Havering Music School The Sampimon Trust immediacy. As we look forward to the 2015/16 Season, the Hall is SEASON PATRONS David and Jacqueline Ansell* The Headley Trust Louise Scheuer Aubrey Adams* Arts Council England The Henry C Hoare Charitable Trust Julia Schottlander* delighted to present some of the greatest artists in the world today, as well American Friends of Wigmore Hall Anthony Austin Nicholas Hodgson Richard Sennett and Saskia Sassen* Karl Otto Bonnier* The Austin & Hope Pilkington Trust André and Rosalie Hoffmann The Shoresh Charitable Trust as talented emerging artists who explore repertoire with skill, curiosity and Cockayne‡ Ben Baglio and Richard Wilson Peter and Carol Honey* Sir Martin and -

Run Time Error Simon Steen-Andersen JACK Quartet

Miller Theatre at Columbia University 2015-16 | 27th Season Opening Night Run Time Error Simon Steen-Andersen JACK Quartet Thursday, September 17, 8:00 p.m. From the Executive Director This September we begin Miller Theatre’s 2015-16 season with three incredible collaborations. Tonight you’ll see Danish composer and performer Simon Steen- Andersen join with one of our favorite ensembles, the JACK Quartet, on a very special project. Run Time Error, the video work that opens and closes this evening, invites us to broaden our sense of both sonic and spatial musical possibility, and it does so in a very personal way: by turning the theatre itself into an instrument. Throughout this new season, Miller Theatre will present performances that bring contemporary classical music out of the formal settings of a concert hall, and Steen-Andersen’s work makes for an exhilarating kick-off. Run Time Error is one of several new works created start-to-finish at Miller this month. As part of an annual collaboration with Deborah Cullen, director and chief curator of Columbia’s Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, this is our third time co- commissioning a visual artist to use our lobby as their canvas. This season, Scherezade Garcia has transformed the space with an amazing new work, inviting anyone who steps inside our doors to activate their imagination. Our largest artistic residency is just about to begin: Morningside Lights! A week of free arts workshops for participants of all ages begins this Saturday, and culminates in a magnificent illuminated procession through Morningside Park on September 26. -

2016/17 Season Preview and Appeal

2016/17 SEASON PREVIEW AND APPEAL The Wigmore Hall Trust would like to acknowledge and thank the following individuals and organisations for their generous support throughout the THANK YOU 2015/16 Season. HONORARY PATRONS David and Frances Waters* Kate Dugdale A bequest from the late John Lunn Aubrey Adams David Evan Williams In memory of Robert Easton David Lyons* André and Rosalie Hoffmann Douglas and Janette Eden Sir Jack Lyons Charitable Trust Simon Majaro MBE and Pamela Majaro MBE Sir Ralph Kohn FRS and Lady Kohn CORPORATE SUPPORTERS Mr Martin R Edwards Mr and Mrs Paul Morgan Capital Group The Eldering/Goecke Family Mayfield Valley Arts Trust Annette Ellis* Michael and Lynne McGowan* (corporate matched giving) L SEASON PATRONS Clifford Chance LLP The Elton Family George Meyer Dr C A Endersby and Prof D Cowan Alison and Antony Milford L Aubrey Adams* Complete Coffee Ltd L American Friends of Wigmore Hall Duncan Lawrie Private Banking The Ernest Cook Trust Milton Damerel Trust Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne‡ Martin Randall Travel Ltd Caroline Erskine The Monument Trust Karl Otto Bonnier* Rosenblatt Solicitors Felicity Fairbairn L Amyas and Louise Morse* Henry and Suzanne Davis Rothschild Mrs Susan Feakin Mr and Mrs M J Munz-Jones Peter and Sonia Field L A C and F A Myer Dunard Fund† L The Hargreaves and Ball Trust BACK OF HOUSE Deborah Finkler and Allan Murray-Jones Valerie O’Connor Pauline and Ian Howat REFURBISHMENT SUMMER 2015 Neil and Deborah Franks* The Nicholas Boas Charitable Trust The Monument Trust Arts Council England John and Amy Ford P Parkinson Valerie O’Connor The Foyle Foundation S E Franklin Charitable Trust No. -

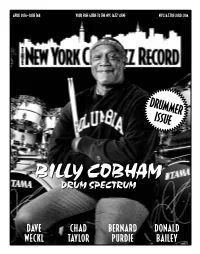

Drummerissue

APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM drumMER issue BILLYBILLY COBHAMCOBHAM DRUMDRUM SPECTRUMSPECTRUM DAVE CHAD BERNARD DONALD WECKL TAYLOR PURDIE BAILEY Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2016—ISSUE 168 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Dave Weckl 6 by ken micallef [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Chad Taylor 7 by ken waxman General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Billy Cobham 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Bernard Purdie by russ musto Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Donald Bailey 10 by donald elfman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Amulet by mark keresman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above FESTIVAL REPORT or email [email protected] 13 Staff Writers CD Reviews 14 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Miscellany 36 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Event Calendar Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, 38 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, As we head into spring, there is a bounce in our step. -

Page | 1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. CARLA BLEY NEA Jazz Master (2015) Interviewee: Carla Bley (May 11, 1936 - ) Interviewer: Ken Kimery Date: September 9, 2014 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 60 pp. Ken Kimery: My name is Ken Kimery. I’m here in wonderful Willow, New York. Blue sky; wonderfully clear air, with Carla Bley. Carla Bley, composer, bandleader, pianist, organist? Umm, doctorate? Umm, raconteur, vocalist, umm, guess I’ve heard you sing. Carla Bley: You have? When was that? Kimery: Well there’s a couple of recordings that I’ve heard you sing on, so... Bley: Oh my god! Kimery: Umm… Bley: Gotta have those destroyed! Kimery: [Laughter] And, uhh, 2015, coming up 2015, National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master. Bley: Isn’t that amazing? Kimery: Thank you very much for allowing me to invade your home here in wonderful Willow, New York, and for the next couple of hours to sit down with you and have you share with us your life story. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Bley: Okay. Kimery: If we can start, if you could give us your full name, and if you don’t mind your birth date, birth year. Bley: Mhmm Kimery: And where you were born. Bley: Well, my full name is not the name I was born with. My real name that I was born with is, oh my god, I think I can say it. -

A Festival of Unexpected New Music February 28March 1St, 2014 Sfjazz Center

SFJAZZ CENTER SFJAZZ MINDS OTHER OTHER 19 MARCH 1ST, 2014 1ST, MARCH A FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 28 FEBRUARY OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC Find Left of the Dial in print or online at sfbg.com WELCOME A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED TO OTHER MINDS 19 NEW MUSIC The 19th Other Minds Festival is 2 Message from the Executive & Artistic Director presented by Other Minds in association 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and SFJazz Center 11 Opening Night Gala 13 Concert 1 All festival concerts take place in Robert N. Miner Auditorium in the new SFJAZZ Center. 14 Concert 1 Program Notes Congratulations to Randall Kline and SFJAZZ 17 Concert 2 on the successful launch of their new home 19 Concert 2 Program Notes venue. This year, for the fi rst time, the Other Minds Festival focuses exclusively on compos- 20 Other Minds 18 Performers ers from Northern California. 26 Other Minds 18 Composers 35 About Other Minds 36 Festival Supporters 40 About The Festival This booklet © 2014 Other Minds. All rights reserved. Thanks to Adah Bakalinsky for underwriting the printing of our OM 19 program booklet. MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WELCOME TO OTHER MINDS 19 Ever since the dawn of “modern music” in the U.S., the San Francisco Bay Area has been a leading force in exploring new territory. In 1914 it was Henry Cowell leading the way with his tone clusters and strumming directly on the strings of the concert grand, then his students Lou Harrison and John Cage in the 30s with their percussion revolution, and the protégés of Robert Erickson in the Fifties with their focus on graphic scores and improvisation, and the SF Tape Music Center’s live electronic pioneers Subotnick, Oliveros, Sender, and others in the Sixties, alongside Terry Riley, Steve Reich and La Monte Young and their new minimalism. -

Norfolk Chamber Music Festival Also Has an Generous and Committed Support of This Summer’S Season

Welcome To The Festival Welcome to another concerts that explore different aspects of this theme, I hope that season of “Music you come away intrigued, curious, and excited to learn and hear Among Friends” more. Professor Paul Berry returns to give his popular pre-concert at the Norfolk lectures, where he will add depth and context to the theme Chamber Music of the summer and also to the specific works on each Friday Festival. Norfolk is a evening concert. special place, where the beauty of the This summer we welcome violinist Martin Beaver, pianist Gilbert natural surroundings Kalish, and singer Janna Baty back to Norfolk. You will enjoy combines with the our resident ensemble the Brentano Quartet in the first two sounds of music to weeks of July, while the Miró Quartet returns for the last two create something truly weeks in July. Familiar returning artists include Ani Kavafian, magical. I’m pleased Melissa Reardon, Raman Ramakrishnan, David Shifrin, William that you are here Purvis, Allan Dean, Frank Morelli, and many others. Making to share in this their Norfolk debuts are pianist Wendy Chen and oboist special experience. James Austin Smith. In addition to I and the Faculty, Staff, and Fellows are most grateful to Dean the concerts that Blocker, the Yale School of Music, the Ellen Battell Stoeckel we put on every Trust, the donors, patrons, volunteers, and friends for their summer, the Norfolk Chamber Music Festival also has an generous and committed support of this summer’s season. educational component, in which we train the most promising Without the help of so many dedicated contributors, this festival instrumentalists from around the world in the art of chamber would not be possible. -

JACK Quartet

Harvard Group for New Music JACK Quartet performs new works for string quartet by Harvard graduate composers 8pm Paine Hall Feb 6 Harvard University ARI STREISFELD violin JACK Quartet JOHN PICKFORD RICHARDS viola CHRISTOPHER OTTO violin KEVIN MC FaRLAND cello CHRIS SWITHINBANK union – seam 2015–16 MANUELA MEIER if only it were not bound to 2016 SIVAN COHEN ELIas Encrypt 2016 ADI SNIR Charasim II: “in sITU” 2015 INTERMISSION KaI JOHANNES POLZHOFER “Echo” from “Totenfest” 2015 JAMES BEAN II. drier 2016 TREVOR BAčA Akasha (आकाश) 2015 Please join us following the concert for a reception in the Taft Lounge downstairs. About the music CHRIS SWITHINBANK union – seam 2015–16 Frayed edge of a space of material dependency. BIO Chris Swithinbank writes: “I work with various combinations of instrumental and electronic resources, mainly fo- cusing on creating musical experiences whose structures attempt to afford space to all the bodies implicated. My current hope with each work is to open up doors to worlds that might otherwise not exist, drawing together material contexts for human performers, which are resistant, re- quire collaborative effort, and disclose the necessity of each constituent part of a whole.” chrisswithinbank.net MANUELA MEIER if only it were not bound to 2016 if only it were not bound to is the latest piece in Manuela’s compositional work that is exploring the ramifications of the idea that sounds are sonic organisms in a sonic environment, with the ability to adapt and evolve. Within this conceptual framework, this piece explores boundaries — and is thus located in borderline areas, living with- in fragile zones at the limits of environs, and the peripheries of the possible. -

The 2018 Guide Festivals

April 2018 The 2018 Guide Festivals FEATURE ARTICLE 10 Questions, Two (Very Different) Festivals Editor’s Note Our fifth annual Guide to Summer Festivals is our biggest yet, with some 85 annotated entries, plus our usual free access to the 1400 listings in the Musical America database. The details for the 85—dates, locations, artistic directors, programming, guest artists, etc.—have been provided by the festivals themselves, in response to a questionnaire sent to our list of Editor’s Picks. Those are determined by a number of factors: it’s hardly a surprise to see the big-budget events, such as Salzburg, Tanglewood, and Aspen, included. But budget is by no means the sole criterion. The 2018 Guide Programming, performers, range and type of events offered—all of these factor into the equation. For our feature article, we chose two highly regarded events and asked them one set of questions, just for the purposes of compare and contrast. Since George Loomis traveled to Ravenna last summer and knows Ojai well, we decided he was the perfect candidate to get the answers. Our hunch that the two couldn’t be more different turned out to be quite accurate: one takes place over a weekend, the over a two-month period; one is in the U.S., the other in Europe; one is rural, the other urban; one’s in a valley, the other by the sea; one focuses on contemporary fare, the other on traditional; one houses its artists in homes, the other in hotels; one is overseen by a man, the other by Festivals a woman; Ojai’s venues are primarily outdoor and strictly 20th century, Ravenna’s are mostly indoor and date as far back as the sixth century.