A Total Approach: the Malaysian Security Model and Political Development Andrew Humphreys University of Wollongong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

Islamic Political Parties and Democracy: a Comparative Study of Pks in Indonesia and Pas in Malaysia (1998-2005)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS ISLAMIC POLITICAL PARTIES AND DEMOCRACY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PKS IN INDONESIA AND PAS IN MALAYSIA (1998-2005) AHMAD ALI NURDIN S.Ag, (UIN), GradDipIslamicStud, MA (Hons) (UNE), MA (NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAM NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2009 Acknowledgements This work is the product of years of questioning, excitement, frustration, and above all enthusiasm. Thanks are due to the many people I have had the good fortune to interact with both professionally and in my personal life. While the responsibility for the views expressed in this work rests solely with me, I owe a great debt of gratitude to many people and institutions. First, I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, who was my principal supervisor before he transferred to Flinders University in Australia. He has inspired my research on Islamic political parties in Southeast Asia since the beginning of my studies at NUS. After he left Singapore he patiently continued to give me advice and to guide me in finishing my thesis. Thanks go to him for his insightful comments and frequent words of encouragement. After the departure of Dr. Priyambudi, Prof. Reynaldo C. Ileto, who was a member of my thesis committee from the start of my doctoral studies in NUS, kindly agreed to take over the task of supervision. He has been instrumental in the development of my academic career because of his intellectual stimulation and advice throughout. -

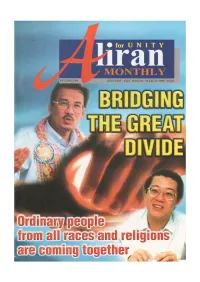

Writes to Guan Eng 4 Guan Eng Replies to Anwar 5 Changing Trmes 8 Three Feasts and a (Soap) Opera 10

u~t·r<~»••nt parties and NGOs, people from all races n!lta•iol'ia are coming together. he Anwar saga has Naturally these different and must be further pro g been an important ral groups with similar goals moted. lying point for the joined forces in the Gagasan reformasi movement. But con and Gerak coalitions to pursue The first item is a set of let cern for Anwar's sacking, as these goals vigorously. ters bet·ween Anwar and sault and unjust treatment Guan Eng from their respec generally have extended into The overall struggle has be tive jails: they exchange fes concern over wider issues. come more comprehensive tive greetings and discuss thb too: Justice for Anwar, for issue of ethnic relations. Sabri The ISA must go. Undemo Guan Eng, for Irene Zain's article Clznllging Times cratic laws must be reviewed Fernandez, for the 126 comments on pre\'ious ethnic so as to guarantee the rakyat's charged for illegal assembly, barriers breaking down. It is rights and liberties. The inde and now, for all prisoners too. a piece that lifts up the spirit. pendence and integrity of the No unjust toll hikes, boycott OJ Muzaffar Tate reports on judiciary, the Attorney irresponsible newspapers, en three functions he attended in Generalis chambers and the sure a free and fair election in Kuala Lumpur, while Anil Police must be restored. Sabah, etc. !\ietto and R.K. Surin write about their e>..perienceattend Cronyism must be gotten rid In this issue of AM, we carry ing a forum in Penang. -

Shell Business Operations Kuala Lumpur:A Stronghold

SHELL BUSINESS OPERATIONS KUALA LUMPUR: A STRONGHOLD FOR HIGHER VALUE ACTIVITIES etting up their operations nearly tial. It sends a strong statement that SBO-KL • SBO-KL’s success in Malaysia two decades ago, The Shell Busi- does not offer a typical GBS location, but was attributed to three key ness Operations Kuala Lumpur offers an entire ecosystem that is constantly aspects – talent quality & (SBO-KL) which is located in growing and developing. availability, world class infra- Cyberjaya, has come a long way. structure, and govt support. SInitially known as Shell IT International (SITI), Frontrunner In The Field • Expansion plans are based on the company has reinvented itself into the Currently, SBO-KL is one of seven global busi- skills, not scale – hiring from multifunctional shared services company ness operations serving clients worldwide, different sectors and industries it is today. with the current focus of being a hub of allows for new markets to be expertise and centre of excellence. tapped into when it comes to Malaysia, Meeting All Requirements Amongst the shared services in Malaysia, creative solutions. The centre’s setup in Malaysia was attributed SBO-KL has the widest portfolio, comprising • High Performance Culture cre- to three key aspects – government support, of business partners and services in the areas ates employees that are holistic talent availability and infrastructure. Having of IT, Finance, HR, Operations, Contracting in thinking and have a desire been granted MSC status, support, and and Procurement, Downstream Business to improve the bottom-line of policies that was favourable, this was a clear (Order-to-delivery, Customer Operation, the organisation. -

For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity

For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity PP3739/12/2008(007145) ISSN 0127 - 5127 RM4.00 2008:Vol.28No.8 Aliran Monthly : Vol.28(8) Page 1 COVER STORY People power shines through candlelight vigils Despite the harsh action of the police on 9 November, the struggle to abolish the ISA will continue by Anil Netto t had been a night laced with drama in II Petaling Jaya as a stand-off ensued be- III tween the rakyat seeking electoral reforms and the repeal of the ISA, on the one hand, and police, who were in a mood to crack down. After having been chased away from the field near Amcorp Mall, the site of their usual vigils, the par- ticipants then entered the mall and gathered in the lobby as riot police lined up facing the entrance, glaring menacingly at them. Some among the crowd then went ‘shopping’ until about 9.30pm. They later dispersed but others adjourned to the PJ Civic Cen- tre not far away for an impromptu gathering. As they were singing the national anthem and about to disperse, riot police and plain-clothes officers marched into the crowd and arrested 23 people. A few protesters complained they were roughed up or assaulted. “Two guys came over to grab one arm each and pushed me towards the Black Maria,’’ wrote MP Tony Pua in his blog. “I stated that I will walk, don’t be rough but they tore my shirt instead. I repeated my call and three other police officers came at me, one with the knees into my belly while an- other attempted to kick my shin.’’ “They then chucked me against the back of the Black Maria truck and shoved me up despite me stating that I can climb myself.’’ Authorities unnerved Most Malaysians were shocked to hear of the police action on the night of Sunday, 9 November, and the arrests of concerned individuals who had turned Aliran Monthly : Vol.28(8) Page 2 EDITOR'S NOTE In our cover story, Anil Netto takes a close look at the ongoing candlelights vigils where ordinary CONTENTS rakyat have been coming out to express their desire for justice and reforms. -

Malaysia's Security Practice in Relation to Conflicts in Southern

LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE Malaysia’s Security Practice in Relation to Conflicts in Southern Thailand, Aceh and the Moro Region: The Ethnic Dimension Jafri Abdul Jalil A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations 2008 UMI Number: U615917 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615917 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Libra British U to 'v o> F-o in andEconor- I I ^ C - 5 3 AUTHOR DECLARATION I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Jafri Abdul Jalil The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted provided that full acknowledgment is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without prior consent of the author. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Pengorbanan Tokoh Melayu Dikenang (BH 27/06/2000)

27/06/2000 Pengorbanan tokoh Melayu dikenang iewed by Salbiah Ani JUDUL: Insan Pejuang Bangsa Melayu Abad Ke-20 PENULIS: Khairul Azmi Mohamad dan AF Yassin PENERBIT: Yayasan Warisan Johor HALAMAN: 146 halaman BUKU Insan Pejuang Bangsa Melayu Abad Ke-20 merakamkan detik bersejarah dalam kehidupan insan yang menjadi peneraju Umno pada awal kebangkitan bangsa Melayu lewat 1940-an. Hambatan dan jerit payah yang terpaksa dilalui pejuang Umno dirakamkan dalam buku ini bagi membolehkan generasi muda berkongsi pengalaman dan menghayati erti pengorbanan. Semua orang Melayu di Malaysia biar bagaimana pendirian politik mereka, terpaksa mengakui hakikat Umno yang menjadi tonggak kepada usaha penyatuan bangsa Melayu bagi mengusir penjajah keluar dari Tanah Melayu. Selain itu, tidak boleh dinafikan Umno juga adalah perintis usaha pembaikan dan pembinaan bangsa yang selama ini diperkotak-katikkan tangan asing. Tokoh yang ditampilkan dalam buku berkenaan ialah Datuk Onn Ja'afar, Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra al-Haj, Tun Abdul Razak Hussein, Tun Hussein Onn, Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Tun Dr Ismail Abd Rahman, Tan Sri Musa Hitam, Tun Abdul Ghafar Baba, Tan Sri Senu Abd Rahman dan Tun Sardon Jubir. Tidak ketinggalan Tan Sri Syed Jaafar Albar, Tan Sri Zainun Munsyi Sulaiman, Tan Sri Fatimah Hashim, Tan Sri Aishah Ghani, Dr Abd Rahman Talib, Tan Sri Zainal Abidin Ahmad, Tan Sri Sulaiman Ninam Shah, Tun Syed Nasir, Abd Aziz Ishak dan Datuk Ahmad Badawi Abdullah Fahim. Sesetengah daripada tokoh pejuang Melayu ini mungkin tidak dikenali sama sekali generasi muda kini kerana mereka lebih dulu menemui Ilahi tetapi sumbangan mereka terus melakari sejarah negara. Penulis buku ini, Dr Khairul Azmi dan AF Yassin, memilih tokoh untuk ditampilkan sebagai pejuang berdasarkan kedudukan mereka sebagai pemimpin tertinggi Umno. -

`Al-Ma'unah Are Terrorists' (HL) (NST 11/07/2000)

11/07/2000 `Al-Ma'unah are terrorists' (HL) Shamsul Akmar; Abdul Razak Ahmad PUTRAJAYA, Mon. - Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad today warned any group against justifying the actions of the Al-Ma'unah group, whom he described as "terrorists" out to topple the Government. "At this time, the people are condemning the actions of the Al-Ma'unah group, but I believe that not long from now, there will be attempts to justify their actions," said Dr Mahathir, who is Umno president, after chairing a special meeting of the party's supreme council to discuss the recent arms heist. The meeting, conducted one week earlier than scheduled, was held at his residence here today. Dr Mahathir singled out Pas as a group which he said would go "all out" to defend the actions of the terrorists. Citing the 1985 Memali incident in Baling, Kedah as an example, Dr Mahathir said Pas, in defending the group of religious fanatics had justified the murder of four policemen killed in the operation. "This will be the opinion voiced by groups whom we know sympathise with these people because they have the same objective - fighting supposedly for the establishment of an Islamic State," he added. The Prime Minister said many people would be swayed by such an opinion and hoped that there would be no Friday sermons (khutbah) or religious lectures aimed at justifying the actions of the Al-Ma'unah. Dr Mahathir said the Government was worried that people would sympathise with the actions of the terrorists if it did not explain the real motive of the group, which he described as belonging to the "lunatic fringe". -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL E/CN.4/2004/62/Add.1 26 March 2004 ENGLISH/FRENCH/SPANISH ONLY COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sixtieth session Agenda item 11 (c) CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS, INCLUDING QUESTIONS OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION The right to freedom of opinion and expression Addendum ∗ Summary of cases transmitted to Governments and replies received ∗ ∗ The present document is being circulated in the language of submission only as it greatly exceeds the page limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions GE.04-12400 E/CN.4/2004/62/Add.1 Page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction 1 – 2 5 SUMMARY OF CASES TRANSMITTED AND REPLIES RECEIVED 3 – 387 5 Afghanistan 3 – 5 5 Albania 6 – 7 6 Algeria 8 – 25 6 Argentina 26 – 34 11 Armenia 35 – 38 13 Azerbaijan 39 – 66 15 Bangladesh 67 – 87 30 Belarus 88 – 94 36 Benin 95 – 96 39 Bolivia 97 – 102 39 Botswana 103 – 106 42 Brazil 107 -108 43 Burkina Faso 109 -111 43 Cambodia 112 – 115 44 Cameroon 116 – 127 45 Central African Republic 128 – 132 49 Chad 133 – 135 50 Chile 136 – 138 51 China 139 – 197 52 Colombia 198 – 212 71 Comoros 213 – 214 75 Côte d’Ivoire 215 – 219 75 Cuba 220 – 237 77 Democratic Republic of the Congo 238 – 257 82 Djibouti 258 – 260 90 Dominican Republic 261 – 262 91 Ecuador 263 – 266 91 Egypt 267 – 296 92 El Salvador 297 – 298 100 Eritrea 299 – 315 100 Ethiopia 316 – 321 104 Gabon 322 – 325 106 Gambia 326 – 328 108 Georgia 329 – 332 109 Greece 333 – 334 111 Guatemala 335 – 347 111 Guinea-Bissau 348 – 351 116 E/CN.4/2004/62/Add.1 -

The Path to Malaysia's Neutral Foreign Policy In

SARJANA Volume 30, No. 2, December 2015, pp. 71-79 THE PATH TO MALAYSIA’S NEUTRAL FOREIGN POLICY IN THE TUNKU ERA Ito Mitsuomi Abstract During the era of Malaya/Malaysia’s first Prime Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, or Tunku as he is commonly referred to, the country was inclined to adopt a neutral foreign policy in the early years of post-independence. Along with other senior ministers, the Tunku’s stance on communism was soft even before Malaya won independence from the British in 1957. However, domestic and international situations at the time did not allow the government to fully implement a neutral foreign policy until the mid-sixties. With the establishment of diplomatic relations with communist countries that included Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, Romania and Bulgaria, the government shifted from a pro-Western policy to a neutral foreign policy nearing the end of the Tunku’s premiership. It was the Tunku, and not his successor Tun Abdul Razak, who was the pioneer in steering the country towards a neutral course. Keywords: Malaya, Tunku Abdul Rahman, Neutralization, Foreign policy, Communism Introduction Neutralism emerged in Europe, especially among the smaller nations, at the beginning of the nineteenth century as an option to protect national sovereignty against incursion by the major powers. By the mid-twentieth century, the concept had pervaded well into Asia. As Peter Lyon puts it, neutralism was almost ubiquitous in Southeast Asia in one form or another (Lyon 1969: 161), with its official adoption by Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar in the 1960s. The new government of Malaya was in a position to choose a neutral policy when the country achieved independence from the British in 1957, but found it inexpedient to do so. -

Umno Dan Krisis; Penelitian Kepada Krisis Dalaman-Kes Terpilih

UMNO DAN KRISIS; PENELITIAN KEPADA KRISIS DALAMAN-KES TERPILIH Ku Hasnan bin Ku Halim1, Ainudin Lee bin Iskandar Lee2, Suhaimi bin Sulaiman 3 1Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia [email protected] 2Universiti Utara Malaysia 3Universiti Malaysia Sabah ABSTRAK Demokrasi (Pilihanraya dan Pemilihan Parti) dan berasaskan amalan kebiasaan. Namun begitu dalam keadaan tertentu proses penggantian kepimpinan ini seringkali pula menimbulkan konflik dan polemik apabila ada keinginan untuk mengetahui kepimpinan itu secara wajarnya walaupun dilakukan atas nama Demokrasi (kebebasan untuk bertanding dan memilih pemimpin). Meskipun tuntutan Demokrasi membenarkan pertandingan (unsur keterbukaan), namun landasan sistem pemerintahan yang terbuka sifatnya itu akan menjadi agenda untuk mempertahankan kepentingan kelompok yang kecil sedangkan majoriti kumpulan yang lain menjadi mangsa akibat dasar liberalisasi serta keterbukaan itu. Maka akan wujud impak serta akibatnya. UMNO sebagai sebuah parti terbesar kepada orang-orang Melayu, telah menempuh tidak kurang daripada lima belas (15) krisis besar sejak parti itu ditubuhkan pada tahun 1946. Di dalam siri-siri krisis tersebut yang berlaku 4 kriteria ini diambil perhatian dan selalu di nilai dan dianalisis iaitu Siapa atau watak utama yang terlibat, Apakah isu-isunya yang terlibat dan dilibatkan, Sebab musabab pemula kepada krisis dan apakah pengakhiran kepada krisis tersebut serta implikasinya. Berasaskan kepada penelitian artikel ini merumuskan bahawa DNA UMNO itu adalah krisis dimana krisis dan konflik itulah