Exploring Plantation Development and Land Cover Changes in the Meme-Mungo Corridor of Cameroon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

MINMAP South-West Region

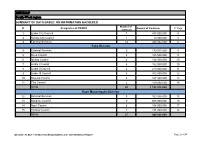

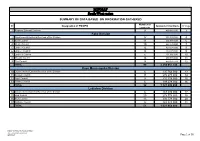

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

SSA Infographic

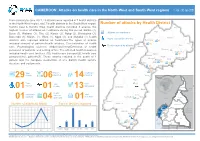

CAMEROON: Attacks on health care in the North-West and South-West regions 1 Jan - 30 Jun 2021 From January to June 2021, 29 attacks were reported in 7 health districts in the North-West region, and 7 health districts in the South West region. Number of attacks by Health District Kumbo East & Kumbo West health districts recorded 6 attacks, the Ako highest number of attacks on healthcare during this period. Batibo (4), Wum Buea (3), Wabane (3), Tiko (2), Konye (2), Ndop (2), Benakuma (2), Attacks on healthcare Bamenda (1), Mamfe (1), Wum (1), Nguti (1), and Muyuka (1) health Injury caused by attacks Nkambe districts also reported attacks on healthcare.The types of attacks Benakuma 01 included removal of patients/health workers, Criminalization of health 02 Nwa Death caused by attacks Ndu care, Psychological violence, Abduction/Arrest/Detention of health Akwaya personnel or patients, and setting of fire. The affected health resources Fundong Oku Kumbo West included health care facilities (10), health care transport(2), health care Bafut 06 Njikwa personnel(16), patients(7). These attacks resulted in the death of 1 Tubah Kumbo East Mbengwi patient and the complete destruction of one district health service Bamenda Ndop 01 Batibo Bali 02 structure and equipments. Mamfe 04 Santa 01 Eyumojock Wabane 03 Total Patient Healthcare 29 Attacks 06 impacted 14 impacted Fontem Nguti Total Total Total 01 Injured Deaths Kidnapping EXTRÊME-NORD Mundemba FAR-NORTH CHAD 01 01 13 Bangem Health Total Ambulance services Konye impacted Detention Kumba North Tombel NONORDRTH 01 04 destroyed 01 02 NIGERIA Bakassi Ekondo Titi Number of attacks by Month Type of facilities impacted AADAMAOUADAMAOUA NORTH- 14 13 NORD-OUESTWEST Kumba South CENTRAL 12 WOUESTEST AFRICAN Mbonge SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC 10 WEST Muyuka CCENTREENTRE 8 01 LLITITTORALTORAL EASESTT 6 5 4 4 Buea 4 03 Tiko 2 Limbe Atlantic SSUDOUTH 1 02 Ocean 2 EQ. -

Predicted Distribution and Burden of Podoconiosis in Cameroon

Predicted distribution and burden of podoconiosis in Cameroon. Supplementary file Text 1S. Formulation and validation of geostatistical model of podoconiosis prevalence Let Yi denote the number of positively tested podoconiosis cases at location xi out of ni sample individuals. We then assume that, conditionally on a zero-mean spatial Gaussian process S(x), the Yi are mutually independent Binomial variables with probability of testing positive p(xi) such that ( ) = + ( ) + ( ) + ( ) + ( ) + ( ) 1 ( ) � � 0 1 2 3 4 5 − + ( ) + ( ) 6 where the explanatory in the above equation are, in order, fraction of clay, distance (in meters) to stable light (DSTL), distance to water bodies (DSTW), elevation (E), precipitation(Prec) (in mm) and fraction of silt at location xi. We model the Gaussian process S(x) using an isotropic and stationary exponential covariance function given by { ( ), ( )} = { || ||/ } 2 ′ − − ′ Where || ||is the Euclidean distance between x and x’, is the variance of S(x) and 2 is a scale − pa′rameter that regulates how fast the spatial correlation decays to zero for increasing distance. To check the validity of the adopted exponential correlation function for the spatial random effects S(x), we carry out the following Monte Carlo algorithm. 1. Simulate a binomial geostatistical data-set at observed locations xi by plugging-in the maximum likelihood estimates from the fitted model. 2. Estimate the unstructured random effects Zi from a non-spatial binomial mixed model obtained by setting S(x) =0 for all locations x. 3. Use the estimates for Zi from the previous step to compute the empirical variogram. 4. Repeat steps 1 to 3 for 10,000 times. -

The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon: a Geopolitical Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal December 2019 edition Vol.15, No.35 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon: A Geopolitical Analysis Ekah Robert Ekah, Department of 'Cultural Diversity, Peace and International Cooperation' at the International Relations Institute of Cameroon (IRIC) Doi:10.19044/esj.2019.v15n35p141 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2019.v15n35p141 Abstract Anglophone Cameroon is the present-day North West and South West (English Speaking) regions of Cameroon herein referred to as No-So. These regions of Cameroon have been restive since 2016 in what is popularly referred to as the Anglophone crisis. The crisis has been transformed to a separatist movement, with some Anglophones clamoring for an independent No-So, re-baptized as “Ambazonia”. The purpose of the study is to illuminate the geopolitical perspective of the conflict which has been evaded by many scholars. Most scholarly write-ups have rather focused on the causes, course, consequences and international interventions in the crisis, with little attention to the geopolitical undertones. In terms of methodology, the paper makes use of qualitative data analysis. Unlike previous research works that link the unfolding of the crisis to Anglophone marginalization, historical and cultural difference, the findings from this paper reveals that the strategic location of No-So, the presence of resources, demographic considerations and other geopolitical parameters are proving to be responsible for the heightening of the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon and in favour of the quest for an independent Ambazonia. -

Programming of Public Contracts Awards and Execution for the 2020

PROGRAMMING OF PUBLIC CONTRACTS AWARDS AND EXECUTION FOR THE 2020 FINANCIAL YEAR CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING LOGBOOK OF DEVOLVED SERVICES AND OF REGIONAL AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES SOUTH-WEST REGION 2021 FINANCIAL YEAR SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 6 219 193 000 3 2 Kumba City Council 1 100 000 000 4 Fako Division 3 Divisional External Services 6 261 261 000 5 4 Buea Council 10 215 928 000 5 5 Idenau Council 10 360 000 000 6 6 Limbe I Council 12 329 000 000 7 7 Limbe II Council 9 225 499 192 8 8 Limbe III Council 13 300 180 000 9 9 Muyuka Council 10 303 131 384 10 10 Tiko Council 8 297 100 000 11 TOTAL 78 2 292 099 576 Kupe Manenguba Division 11 Divisional External Services 2 47 500 000 12 12 Bangem Council 9 267 710 000 12 13 Nguti Council 8 224 000 000 13 14 Tombel Council 10 328 050 000 13 TOTAL 29 867 260 000 Lebialem Division 15 Divisional External Services 1 32 000 000 15 16 Alou Council 13 253 000 000 15 17 Menji Council 4 235 000 000 16 18 Wabane Council 10 331 710 000 17 TOTAL 28 851 710 000 Manyu Division 19 Divisional External Services 1 22 000 000 18 20 Akwaya Council 7 339 760 000 18 21 Eyumojock Council 8 228 000 000 18 22 Mamfe Council 10 230 000 000 19 23 Tinto Council 9 301 760 000 20 TOTAL 35 1 121 520 000 MINMAP/Public Contracts Programming and Monitoring Division Page 1 of 30 SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Meme Division 24 -

Cameroon - South-West Region ! H Administrative Breakdowns NIGER

Cameroon - South-West Region ! h Administrative Breakdowns NIGER CHAD N N " NIGERIA " 0 0 ' !Mfom ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 6 ! Iyahe 6 !Akumaye !Ngale !Wum CAMEROON CAR !Nkim EQUATORIAL GUINEA GABON CONGO NIGERIA NORTH-WEST AKWAYA !Bafut N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 !Acha Tugui 0 ° ° 6 6 !Ikom !Bamenda !Bali Baliben MANYU ! ! Mamfe Ayukaba ! Bachuo Akagbe ! WABANE EYUMODJOCK UPPER BAYANG LEBIALEM !Mbouda MAMFE ALOU N N " Bamougo!um " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 3 3 ° ° 5 5 ! Dschang FONTEM ! WEST ! Old Dunlop Town ! !Oban Company NGUTI ! KUPE-MANENGUBA TOKO !Kekem !Bafang !Melong SOUTH-WEST BANGEM !Passim N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 5 Calabar MUNDEMBA 5 ! !Nkongsamba !Ikot Offiong KONYE NDIAN TOMBEL !Manjo !Oron ! ISANGELE Tombel DIKOME BALUE ! Loum CAMEROON KUMBA ! KOMBO ITINDI EKONDO TITI 2ND Penja !Kumba ! KOMBO MEME !Ekondo Titi ABEDIMO KUMBA 3RD KUMBA 1ST N N " " 0 0 ' !Mbanga CENTRE ' 0 Longtoka 0 3 IDABATO ! 3 ° ° 4 BAMUSSO 4 !Ndokbélé !Mweli LITTORAL MBONGE MBONGE MUYUKA !Muyuka !Kaké !\ National capital FAKO !! Major Town WEST-COAST Bomono Gare ! BUEA ! Intermediate Town ! !Bonépoupa II ! Bomono Ba Buea ! Mbengué Small Town Mutengene ! TIKO ! International boundary Tiko Douala LIMBE !! LIMBE 2ND ! N N " 1ST Region boundary " 0 0 ' Limbe ' 0 0 ° ° 4 LIMBE 3RD 4 Department boundary Commune boundary ± River 0 10 20 E40QUATORIAL Surface Waterbody Kilometres !Edéa 8°30'0"E GUINEA 9°0'0"E 9°30'0"E 10°0'0"E Date Created: 20 Dec 2018 - Contact: [email protected] Data sources: Boundaries: OCHA, The designations employed and the presentation of material in the map(s) do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of WFP concerning Website: www.logcluster.org - Prepared by: HQ, OSE GIS ©OpenStreetMap Contributors © World Food Programme 2018 the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory, city or sea, or Map Reference: CMR_ADMIN_SudOuest_A3P_20181128 Populated places: GeoNames concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

2015 Annual Report

1 Annual report (2014/2015) Acknowledgment This report covers the activities carried out by AJESH in 2015.The results of the works here reported are realisations by all the staff of AJESH. AJESH would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the representatives of the Ministries, local, national and international NGOs, and local community representative who gave their time, ideas and contributed positively during the implementation of our projects. In particular, the AJESH team appreciates RFUK, EU-PASC, Plan International (Cameroon Office), FODER, CED, IRESCO, LTS International, Rainbow Environment Consult, WRI, Eyes on Africa, Transparency International (Cameroon) for providing the necessary financial and material support that enabled the realisation and attainment of some of our project objectives. In addition, AJESH wishes to express its appreciation to all partners: the Administrators of Nguti and Eyumojock, the DMOs for Tombel, Mbonge, Ekond Titi, and Kumba, other National NGO and SCOs, for their tireless support in seeing that planned activities are realised within the state norms. We equally appreciate the Green Vision Newspaper for all their publication and visibility of AJESH’s activities. We equally wish to express our hearty thanks to University of Wolverhampton UK, Well Grounded, MINFOF (C2D PSFE2), RFUK, PASC, for building staff capacities on: forest Governance, Leadership, Project development, Community Support, Advocacy, Accountability and Transparency, etc. Finally, but most importantly, the AJESH team would like to thank the Mayor of Nguti for hosting most of our meetings in the Council Chambers free of charge, the Member of Parliament for Nguti, and the Chiefs and members of the Communities who walked and travelled for many hours through notoriously difficult roads to attend our meeting and participating effectively in the implementation of our activities in their villages. -

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 329 101 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 10 184 301 000 4 3 Buea Council 9 148 093 000 5 4 Idenau Council 9 248 200 000 6 5 Limbe I Council 8 149 350 000 7 6 Limbe II Council 13 326 200 000 8 7 Limbe III Council 18 369 350 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 9 196 947 000 12 9 Tiko Council 12 381 200 000 13 TOTAL 88 2 003 641 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 2 55 000 000 15 11 Bangem Council 10 253 700 000 15 12 Nguti Council 8 266 700 000 16 13 Tombel Council 8 395 000 000 17 TOTAL 28 970 400 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 2 37 000 000 19 15 Alou Council 8 277 700 000 19 16 Menji Council 5 147 700 000 20 17 Wabane Council 9 273 000 000 21 TOTAL 24 735 400 000 Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 2 39 500 000 23 19 Akwaya Council 11 293 842 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 5 180 700 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 10 571 832 532 25 22 Tinto Council 11 254 769 714 26 TOTAL 39 1 340 644 246 MINMAP/Public Contracts Programming and Monitoring Division Page 1 of 42 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 5 182 000 000 28 24 Kumba I Council 6 115 134 500 28 25 Kumba II Council -

Sightsavers Deworming Program – Cameroon Givewell Wishlist 3 Schistosomiasis (SCH) / Soil Transmitted Helminth (STH) Project Narrative

Sightsavers Deworming Program – Cameroon GiveWell Wishlist 3 Schistosomiasis (SCH) / Soil Transmitted Helminth (STH) Project Narrative Country: Cameroon Location (region/districts): South-West, North-West, West, Far North, North, Littoral, East, Adamaoua Duration of project: 3 years Start date: April 2019 Goal Reduction in the prevalence and intensity of SCH and STH amongst school age children. Outcome School aged children (SAC) between 5 -15 years, and adults where prevalence dictates, within the intervention zone are effectively treated with mebendazole/albendazole and praziquantel as required. Program implementation areas Sightsavers is supporting SCH / STH mass drug administration (MDA) in three regions of South West, North West and West Cameroon in 2018 with funding from GiveWell’s quarterly payments. Wishlist 3 will extend this support in existing implementation areas for an additional two years to help control SCH and STH in compliance with the National NTD Program policies. We have divided the Wishlist 3 funding request into three priorities that constitute a nationwide program. Sightsavers will only expand cumulatively, i.e. each consecutive priority builds upon the ask of the previous priority. Priority 1: SCH/STH MDA in our existing operational regions of West, North-West, and South- West. Our current approach of using GiveWell’s quarterly allocations is not sustainable. The funding available through quarterly allocations varies. To enable a well-planned program we need secured funding to ensure resources are allocated appropriately. We therefore request grant funding to continue implementation of the SCH/STH program in the West, North-West and South- West regions from April 2019 – Mar 2022. Priority 2: SCH/STH MDA in North and Far North regions The two northern regions are the second priority because Sightsavers’ staff on the ground work in collaboration with HKI to support the MoH in the implementation of the trachoma programme (SAFE activities).