Deep Earth. (M)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carnegie Institution of Washington Department of Terrestrial Magnetism Washington, DC 20015-1305

43 Carnegie Institution of Washington Department of Terrestrial Magnetism Washington, DC 20015-1305 This report covers astronomical research carried out during protostellar outflows have this much momentum out to rela- the period July 1, 1994 – June 30, 1995. Astronomical tively large distances. Planetary nebulae do not, but with studies at the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism ~DTM! their characteristic high post-shock temperatures, collapse of the Carnegie Institution of Washington encompass again occurs. Hence all three outflows appear to be able to observational and theoretical fields of solar system and trigger the collapse of molecular clouds to form stars. planet formation and evolution, stars and star formation, Foster and Boss are continuing this work and examining galaxy kinematics and evolution, and various areas where the possibility of introducing 26Al into the early solar system these fields intersect. in a heterogeneous manner. Some meteoritical inclusions ~chondrules! show no evidence for live 26Al at the time of their formation. So either the chondrules formed after the 1. PERSONNEL aluminium had decayed away, or the solar nebula was not Staff Members: Sean C. Solomon ~Director!, Conel M. O’D. Alexander, Alan P. Boss, John A. Graham, Vera C. Rubin, uniformly populated with the isotope. Foster & Boss are ex- Franc¸ois Schweizer, George W. Wetherill ploring the injection of shock wave particles into the collaps- Postdoctoral Fellows: Harold M. Butner, John E. Chambers, ing solar system. Preliminary results are that ;40% of the Prudence N. Foster, Munir Humayun, Stacy S. McGaugh, incident shock particles are swallowed by the collapsing Bryan W. Miller, Elizabeth A. Myhill, David L. -

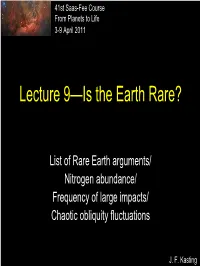

Lecture 9—Is the Earth Rare?

41st Saas-Fee Course From Planets to Life 3-9 April 2011 Lecture 9—Is the Earth Rare? List of Rare Earth arguments/ Nitrogen abundance/ Frequency of large impacts/ Chaotic obliquity fluctuations J. F. Kasting The Gaia hypothesis First presented in the 1970s by James Lovelock 1979 1988 • Life itself is what stabilizes planetary environments • Corollary: A planet might need to be inhabited in order to remain habitable The Medea and Rare Earth hypotheses Peter Ward 2009 2000 Medea hypothesis: Life is harmful to the Earth! Rare Earth hypothesis: Complex life (animals, including humans) is rare in the universe Additional support for the Rare Earth hypothesis • Lenton and Watson think that complex life (animal life) is rare because it requires a series of unlikely evolutionary events – the origin of life – the origin of the genetic code – the development of oxygenic photosynthesis) – the origin of eukaryotes – the origin of sexuality 2011 Rare Earth/Gaia arguments 1. Plate tectonics is rare --We have dealt with this already. Plate tectonics is not necessarily rare, but it requires liquid water. Thus, a planet needs to be within the habitable zone. 2. Other planets may lack magnetic fields and may therefore have harmful radiation environments and be subject to loss of atmosphere – We have talked about this one also. Venus has retained its atmosphere. The atmosphere itself provides protection against cosmic rays 3. The animal habitable zone (AHZ) is smaller than the habitable zone (HZ) o – AHZ definition: Ts = 0-50 C o – HZ definition: Ts = 0-100 C. But this is wrong! For a 1-bar atmosphere like Earth, o water loss begins when Ts reaches 60 C. -

Chapter 9: the Origin and Evolution of the Moon and Planets

Chapter 9 THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF THE MOON AND PLANETS 9.1 In the Beginning The age of the universe, as it is perceived at present, is perhaps as old as 20 aeons so that the formation of the solar system at about 4.5 aeons is a comparatively youthful event in this stupendous extent of time [I]. Thevisible portion of the universe consists principally of about 10" galaxies, which show local marked irregularities in distribution (e.g., Virgo cluster). The expansion rate (Hubble Constant) has values currently estimated to lie between 50 and 75 km/sec/MPC [2]. The reciprocal of the constant gives ages ranging between 13 and 20 aeons but there is uncertainty due to the local perturbing effects of the Virgo cluster of galaxies on our measurement of the Hubble parameter [I]. The age of the solar system (4.56 aeons), the ages of old star clusters (>10" years) and the production rates of elements all suggest ages for the galaxy and the observable universe well in excess of 10" years (10 aeons). The origin of the presently observable universe is usually ascribed, in current cosmologies, to a "big bang," and the 3OK background radiation is often accepted as proof of the correctness of the hypothesis. Nevertheless, there are some discrepancies. The observed ratio of hydrogen to helium which should be about 0.25 in a "big-bang" scenario may be too high. The distribution of galaxies shows much clumping, which would indicate an initial chaotic state [3], and there are variations in the spectrum of the 3OK radiation which are not predicted by the theory. -

Dynamical Models of Terrestrial Planet Formation

Dynamical Models of Terrestrial Planet Formation Jonathan I. Lunine, LPL, The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ USA, 85721. [email protected] David P. O’Brien, Planetary Science Institute, Tucson AZ USA 85719 Sean N. Raymond, CASA, University of Colorado, Boulder CO USA 80302 Alessandro Morbidelli, Obs. de la Coteˆ d’Azur, Nice, F-06304 France Thomas Quinn, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington, Seattle USA 98195 Amara L. Graps, SWRI, Boulder CO USA 80302 Revision submitted to Advanced Science Letters May 23, 2009 Abstract We review the problem of the formation of terrestrial planets, with particular emphasis on the interaction of dynamical and geochemical models. The lifetime of gas around stars in the process of formation is limited to a few million years based on astronomical observations, while isotopic dating of meteorites and the Earth-Moon system suggest that perhaps 50-100 million years were required for the assembly of the Earth. Therefore, much of the growth of the terrestrial planets in our own system is presumed to have taken place under largely gas-free conditions, and the physics of terrestrial planet formation is dominated by gravitational interactions and collisions. The ear- liest phase of terrestrial-planet formation involve the growth of km-sized or larger planetesimals from dust grains, followed by the accumulations of these planetesimals into ∼100 lunar- to Mars- mass bodies that are initially gravitationally isolated from one-another in a swarm of smaller plan- etesimals, but eventually grow to the point of significantly perturbing one-another. The mutual perturbations between the embryos, combined with gravitational stirring by Jupiter, lead to orbital crossings and collisions that drive the growth to Earth-sized planets on a timescale of 107 − 108 years. -

The Iron Planet Sex and Skin Color

PERIODICALS Yet, this is the key to the lesson, Kass says. necessary condition for national self- "God's dispersion of the nations is the PO- awareness and the possibility of a politics litical analog to the creation of woman: in- that will. hearken to the voice of what is stituting otherness and opposition, it is the eternal, true, and good." SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY ''Mercu~'~Heart of Iron" by Clark R. Chapman, in Asfrononzy The Iron Planet (Nov. 19881, 1027 N. 7th St., Milwaukee, Wisc. 53233. More than a decade after America's un- plays a vita1 role in the two leading theo- manned Mariner 10 flew near the planet ries of the origins of the solar system. Ac- Mercury during 1974-75, scientists have fi- cording to one theory, formulated by cos- nally digested all of the data from the mochemist John Lewis during the 1970~~ flight. And they are starting to ask some the solar system was created in a more or big questions, reports Chapman, of Tuc- less orderly fashion. Lewis believes that son's Planetary Science Institute. the planets formed out of gases that cooled Located about midway between the and condensed. At some point, billions of Earth and the Sun, Mercury is a "truly bi- years ago, the sun flared up briefly, blast- zarre" planet. Its rock cmst is unusually ing away many gases. According to Lewis's thin; a "metallic iron core" accounts for theory, there should not be any sulfur, or 70 percent of the planet's weight. anything like it, on Mercury. The most surprising discovery made by A more recent theory, propounded by Mariner 10 was that the tiny planet has a George Wetherill of the Carnegie Institu- magnetic field, like Earth's but much tion, is that the solar system emerged from weaker. -

Complex Life, by Jove!

Complex Life, By Jove! By: Leslie Mullen The gas giants in our solar system. From left: Neptune, Uranus, Saturn, and Jupiter. Credit: NASA One of the tenets of astrology is that the positions of the planets affect us. For instance, the position of the planet Jupiter in your chart is supposed to indicate good luck for a certain aspect of your life. In an eerie echo of astrology, some scientists are now saying that the position of Jupiter in our solar system was very good luck for life on Earth. Jupiter is about 5 astronomical units (AU) away from the Sun − far enough away from Earth to not have interfered with the development of our planet, and yet close enough to gravitationally deflect asteroids and comets, limiting the number of dangerous impacts. Impacts by asteroids and comets can create cataclysmic events that destroy life − witness the demise of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, widely believed to have been brought about by a "killer" asteroid impact. Without Jupiter, instead of being hit with a killer asteroid every hundred million years or so, we´d get one every 10,000 years. This reduction in impacts enabled the Earth to develop both simple and complex forms of life. But gas giant planets like Jupiter don´t always help in the development of complex life. Consider, for instance, that while Jupiter deflects many asteroids away from Earth, it also is responsible for most of the asteroids in the first place. When planetesimals were clumping together to form the terrestrial planets, the gravitational influence of Jupiter prevented a fifth planet from forming. -

Obituaries Prepared by the Historical Astronomy Division

1274 Obituaries Prepared by the Historical Astronomy Division WULFF-DIETER HEINTZ, 1930-2006 also gained practical training in meridian circles and position Wulff Dieter Heintz, Professor Emeritus of Astronomy at micrometers, and learned to make binary star observations Swarthmore College, passed away at his home on 10 June with the old Fraunhofer refractor ͑1835͒ of the Munich Ob- 2006, following a two-year battle with lung cancer. He had servatory. It was here that his passion for binary stars was turned seventy-six just one week earlier. Wulff was a leading born. authority on visual double stars and also a chess master. A In 1953, Munich University awarded Wulff the degree of prominent educator, researcher, and scholar, Wulff was Doktor rerum naturalis in astronomy, which he completed noted for being both succinct and meticulous in everything under the direction of Felix Schmeidler. Wulff was almost he did. immediately recruited by the Munich University Observatory Wulff Heintz was born on 3 June 1930 in WXrzburg ͑Ba- to serve as the Scientific Assistant at the Southern Station in varia͒, Germany. Naturally left-handed, his elementary Mount Stromlo, Australia. He worked at Mount Stromlo school teachers forced him to learn to write ‘‘correctly’’ us- from 1954 to 1955, then returned to Munich to serve as ing his right hand, and so he became ambidextrous. During Research Officer from 1956-69, during which time he visited the 1930s, Wulff’s family saw the rise of Adolf Hitler and both the United Kingdom and the United States. Wulff was lived under the repressive Nazi regime. -

2006 Fall.Pdf

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CARNEGIE INSTITUTION [FALL 2006] [PAGE 3] [PAGE 10] [PAGE 11] Inside 3 Embryology Alumnus Andrew Z. Fire Shares Nobel Prize 4 Tipping the Mass Scales at the Edge of the Visible Universe 6 Small-scale Logging Blazes the Trail for Deforestation 7 Sugar Metabolism Tracked in Living Plant Tissues in Real Time 9 Minerals Go “Dark” Near Earth’s Core 10 More Awards: Two Other Carnegie Luminaries Honored 12 Mice Aid the Study of Human Eye Cancer 13 Carnegie’s George West Wetherill, Father of Earth-Formation Models, Dies at 80 14 Why Waves Go Wacky at Earth’s Center 14 Three New “Trojan” Asteroids Found Sharing Neptune’s Orbit 16 In Brief 20 David Greenewalt Building Dedicated at Broad Branch Road Ȝ Ȝ Ȝ Ȝ Ȝ Ȝ Ȝ DEPARTMENT GEOPHYSICAL DEPARTMENT THE DEPARTMENT DEPARTMENT CASE/ OF EMBRYOLOGY LABORATORY OF GLOBAL OBSERVATORIES OF PLANT OF TERRESTRIAL FIRST LIGHT ECOLOGY BIOLOGY MAGNETISM 2 As an institution founded with a mandate to conduct basic scientific research, Carnegie can often appear removed from the problems that dominate our headlines. Indeed, stories of violent crime, scandal, and complicated political problems can sometimes seem like dispatches from another frontier. The institution also seems distant from people who tackle issues of social gravity. One could easily conclude that Carnegie’s explorations of the nature of life, the Earth, and the cosmos have little to do with issues that are germane to our daily lives. Is this perceived gulf as wide as it seems? As a nonscientist, I am struck by how the passage of time can illuminate the value of basic research. -

Uranus, Neptune, and the Mountains of the Moon

PSRD: Uranus and Neptune: Late Bloomers http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/Aug01/bombardment.html posted August 21, 2001 Uranus, Neptune, and the Mountains of the Moon --- The tardy formation of Uranus and Neptune might have caused the intense bombardment of the Moon 3.9 billion years ago. Written by G. Jeffrey Taylor Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology Huge circular basins, marked by low regions surrounded by concentric mountain ranges, decorate the Moon. The giant holes may have formed during a short, violent period from about 3.9 to 3.8 billion years ago. Three hundred to 1000 kilometers in diameter, their sizes suggest that fast-moving objects with diameters of 20 to about 150 kilometers hit the Moon. Numerous smaller craters also formed. If most large lunar craters formed between 3.9 and 3.8 billion years ago, where were the impactors sequestered for over 600 million years after the Moon formed? One possibility has been studied with computer simulations by Harold Levison and colleagues from the Southwest Research Institute (Boulder, Colorado), Queen's University (Ontario, Canada), and NASA Ames Research Center in California. The idea, originally suggested in 1975 by George Wetherill (Carnegie Institution of Washington), is that a large population of icy objects inhabited the Solar System beyond Saturn. They were in stable orbits around the Sun for several hundred million years until, for some reason, Neptune and Uranus began to form. As the planets grew by capturing the smaller planetesimals, their growing gravitational attraction began to scatter the remaining planetesimals, catapulting millions of them into the inner Solar System. -

The Origin of the Earth What's New?

The Origin of the Earth What’s New? Alex N. Halliday1 rogress in understanding the origin of the Earth has been dramatic in been present. The relative propor- tions of aluminum-26 and iron-60 recent years, which is timely given the current search for other habitable are consistent with production in a Psolar systems. At the present time we do not know whether our solar supernova. system, with terrestrial planets located within a few astronomical units2 of a solar-mass star, is unusual or common. Neither do we understand where the DISKS AND PLANET FORMATION water that made Earth habitable came from, nor whether life in the Universe Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and is rare or plentiful. Perhaps something unusual happened here on Earth. Pierre-Simon de Laplace (1749–1827) However, the timescales over which the Sun and solar system formed, as well both argued that the solar system as the detailed mechanisms involved, have been the subjects of extensive originated from a swirling disk of gas and dust (FIG. 1). In 1755, Kant recent studies. Discoveries have resulted mainly from improved mass spectro- proposed the idea that the planets metric measurements leading to a resolution of just 100,000 years accreted from circumstellar dust in some cases. This short review explains some of these developments. under gravity. Laplace presented a similar model in 1796 and KEYWORDS: early Earth, solar system, core formation, planets, explained mathematically the geochemistry, cosmochemistry, isotopes rotation of the disk and planets. This resulted from the increase in angular momentum associated THE BIRTH OF THE SUN with the contraction of the solar nebula as it collapsed to The solar system formed 4.5–4.6 billion years ago (Patterson form the Sun. -

New Data, New Ideas, and Lively Debate About Mercury

PSRD: 2001 Mercury Conference http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/Oct01/MercuryMtg.html posted October 22, 2001 New Data, New Ideas, and Lively Debate about Mercury --- A hundred scientists gathered to share new data and ideas about the important little planet closest to the Sun. Written by G. Jeffrey Taylor Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology Mercury is an important planet. It is closest to the Sun, so its chemical composition helps us test ideas for how the planets formed. In contrast to Venus and Mars, Mercury is generating a magnetic field today--useful in understanding Earth's magnetic field. It has a huge metallic core compared to the other rocky planets. Its cratered, lunar-like surface records a fascinating geologic history. A hundred scientists attended a conference about this important little planet. It was held at the Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois, and was sponsored by the Museum, the Lunar and Planetary Institute, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Mariner 10, the only space mission to Mercury, flew by it three times in 1974 and 1975. Reworking the data in light of a better understanding of remote sensing and using new image analysis techniques is leading to amazing new insights about the planet's origin and geological evolution. And although we have had only one mission to the planet, there are a growing number of astronomical observations from Earth to study the tenuous and complicated mecurian atmosphere. Radar observations are providing dramatic new views of the surface and have revealed mysterious deposits (probably of water ice) in the polar regions. -

David Williams to Speak on the Tectonics of Venus by John Graham

National Capital Astronomers, Inc. Washington, DC (301) 320-3621 Volume L, Number.l9' ~ May 1992 ISSN 0898-7548 David Williams To Speak On The Tectonics of Venus by John Graham The next meeting of National Capital Astrono does Venus transmit stress and expel heat from its mers will be on May 2, 1992 ar7:30 PM at the interior? Theabilityto answerthesequestions will National Institutes ofHealth (the Bunim Room at depend to a large part on understanding how the the Clinical Center on Floor 9, Building 10). On surface of the Earth interacts with its interior and this occasion we shall be addressed by Dr. David what differences between Venus and Earth could Williams from the Department of Terrestrial be causing differences in this interaction. Magnetism of the Carnegie Institution of Wash ington on the subject "The Tectonics of Venus". Dr. Williams was born and grew up in Commack, New York. He obtainedhis firstdegree atthe State The outer shell of the Earth is divided into about University ofNew York at Binghamton. Follow ten largerigidplates which are in slow butdistinct ing this, he went to the University ofCalifornia at motion relative to one another, with deformation Los Angeles for graduate studies where he wrote of these plates largely confined to the vicinity of a dissertation dealing with tectonics and gravity in the boundaries between them. Their movement Venus. Aftera stayatArizonaStateUniversity,he represents the mechanism by which the Earth cameto WashingtoninJuly 1991 where he contin transmits stressand loses internal heat. Therecent ues his interest in Venus tectonics and also col results from the radar images of the surface of laborates with Dr.