An Exploration of How the Novel Form Responds to Digital Interactivity Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSLO Casting Announcement

MICHAEL ARONOV, ADAM DANNHEISSER, JENNIFER EHLE, DANIEL JENKINS, DARIUSH KASHANI, JEFFERSON MAYS, DANIEL ORESKES, HENNY RUSSELL, JOSEPH SIRAVO, T. RYDER SMITH TO BE FEATURED IN THE LINCOLN CENTER THEATER PRODUCTION OF “OSLO” a new play by J.T. ROGERS directed by BARTLETT SHER PREVIEWS BEGIN THURSDAY, JUNE 16 OPENING NIGHT IS MONDAY, JULY 11 AT THE MITZI E. NEWHOUSE THEATER Lincoln Center Theater (under the direction of André Bishop) has announced that Michael Aronov, Adam Dannheisser, Jennifer Ehle, Daniel Jenkins, Dariush Kashani, Jefferson Mays, Daniel Oreskes, Henny Russell, Joseph Siravo, and T. Ryder Smith will be featured in the cast of its upcoming production of OSLO, a new play by J.T. Rogers, directed by Bartlett Sher. Commissioned by Lincoln Center Theater, OSLO begins performances Thursday, June 16 and will open Monday, July 11 at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater (150 West 65 Street). Additional casting will be announced at a later date. It’s 1993. The world watches the impossible: Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat, standing together in the White House Rose Garden, signing the first ever peace agreement between Israel and the PLO. How were the negotiations kept secret? Why were they held in a castle in the middle of Norway? And who are these mysterious negotiators? A darkly comic epic, OSLO tells the true, but until now, untold story of how one young couple, Norwegian diplomat Mona Juul (to be played by Jennifer Ehle) and her husband social scientist Terje Rød-Larsen (to be played by Jefferson Mays), planned and orchestrated top-secret, high-level meetings between the State of Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, which culminated in the signing of the historic 1993 Oslo Accords. -

Eppie's Great Race Team Sets Time to Beat

FOUR EASY TREATS FOR THE FOURTH OF JULY Page 7 ExtremelyCordova Competitive Football Grapevine at Camp Page 14 VOLUMEI 47 • ISSUEndependent 2527 SLIM RANDLES' HOME COUNTRY PROUDLYPROUDLY SERVING SERVING RANCHO RANCHO CORDOVA CORDOVA & & SACRAMENTO SACRAMENTO COUNTY COUNTY Celebrating All Weekend for Independence Day Rancho Cordova Gears Up for the Fourth of July Festival June July 19, 3, 2015 RANCHO CORDOVA, CA (MPG) - freedom in a 5K fun run. Wave the flag at a hometown parade. Spend a couple of days along the beautiful American River, Exercise topped your New Red Light Page 14 off with some of the most spectacular fire works in the region. The two-day Rancho Cordova Fourth of Digital Camera O SAY CAN’T YOU July celebration returns for its 31st year on July 3rd and 4th, and organizers say they’re - System Location SEE, MY BROTHER confident they have something for everyone. RANCHO CORDOVA, CA (MPG) No event captures the spirit of Rancho - The Rancho Cordova Police Cordova like the Rancho Cordova Fourth of Department’s Red Light Photo July Festival. It may have something to do Enforcement Program has placed a with the long affiliation with the nation’s new digital red light photo enforce E defense rooted at the former Mather Air ment camera system on Sunrise ND Force Base or Aerojet company, which Boulevard at Folsom Boulevard, OF THE together gave birth to Rancho Cordova. within the City of Rancho Cordova. - Whatever the reason may be, no community The new system is currently being BENCH puts more into their Fourth of July obser tested and is scheduled to go “live” vance than Rancho Cordova. -

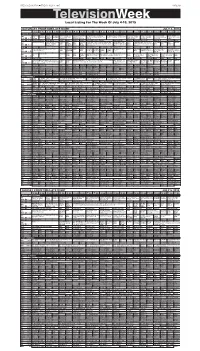

Televisionweek Local Listing for the Week of July 4-10, 2015

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, JULY 3, 2015 PAGE 9B TelevisionWeek Local Listing For The Week Of July 4-10, 2015 SATURDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT JULY 4, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS America’s Victory Prairie America’s Classic Gospel The The Lawrence Welk A Capitol Fourth Celebrating A Capitol Fourth Celebrating No Cover, No Mini- Austin City Limits Front and Center Globe Trekker Yor- PBS Test Garden’s Yard and Heartlnd Homecoming family Show A salute to America’s birthday. (N) (In Stereo America’s birthday. (In Stereo) Å mum Chancey Wil- Country singer Eric Rock band Counting ùbáland; witch doctors KUSD ^ 8 ^ Kitchen Garden performs. Å Broadway musicals. Live) Å liams performs. Church. Å Crows. Å in Oyo. KTIV $ 4 $ Motorcycle Racing Horse Racing Estate News News 4 Insider Macy’s 4th of July Fireworks July Fireworks News 4 Saturday Night Live Å Extra (N) Å 1st Look House Motorcycle Racing Horse Racing Belmont Paid Pro- NBC KDLT The Big Macy’s 4th of July Fireworks Spectacular Macy’s 4th of July KDLT Saturday Night Live Host Amy The Simp- The Simp- KDLT (Off Air) NBC Oaks & Suburban gram Nightly News Bang Starbursts blaze above the Big Apple. (N) (In Fireworks Spectacu- News Adams; One Direction performs. (In sons sons News Å KDLT % 5 % Handicap. (N) News (N) (N) Å Theory Stereo Live) Å lar Å (N) Å Stereo) Å KCAU ) 6 ) 30 for 30 30 for 30 (N) Joint ABC News Edition Astronaut-Club Bruce Jenner -- The Interview Å News Glee “Nationals” Paid The Good Wife Blue Bloods Å PGA Tour Golf Greenbrier Classic, Third Paid Pro- CBS Eve- News Home The Mill- The Mill- The Mc- The Mc- 48 Hours (In Ste- News The White Entertainment To- The Good Wife Eli Leverage The team CBS Round. -

2021 SPRING Pan Macmillan Spring Catalogue 2021.Pdf

PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] * * * * * * * Alice Dewing Rosie Wilson [email protected] [email protected] Amy Canavan Siobhan Slattery [email protected] [email protected] Camilla Elworthy [email protected] * * * * * * * Elinor Fewster [email protected] FREELANCE Emma Bravo Anna Pallai [email protected] [email protected] Gabriela Quattromini Caitlin Allen [email protected] [email protected] Grace Harrison Emma Draude [email protected] [email protected] Hannah Corbett Emma Harrow [email protected] [email protected] Jess Duffy Jamie-Lee Nardone [email protected] [email protected] Kate Green Laura Sherlock [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan Ruth Cairns [email protected] [email protected] CONTENTs PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY MANTLE MACMILLAN PAN TOR BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT PICADOR The War of the Poor Eric Vuillard A short, brutal tale by the author of The Order of The Day: the story of a moment in Europe’s history when the poor rose up and banded together behind a fiery preacher, to challenge the entrenched powers of the ruling elite. The fight for equality begins in the streets. The history of inequality is a long and terrible one. And it’s not over yet. Short, sharp and devastating, The War of the Poor tells the story of a brutal episode from history, not as well known as tales of other popular uprisings, but one that deserves to be told. Sixteenth-century Europe: the Protestant Reformation takes on the powerful and the privileged. -

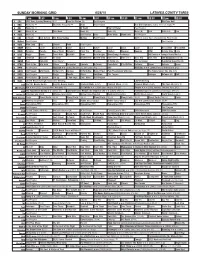

Sunday Morning Grid 6/28/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/28/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Red Bull Signature Series From Las Vegas. Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Vista L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Golf U.S. Senior Open Championship, Final Round. 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Bodyguard ›› (R) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Madison ›› (2001) Jim Caviezel, Jake Lloyd. -

Final Rounds

TVhome The Daily Home April 26 - May 2, 2015 Final Rounds The ever-smitten Eddie (Paul Schulze, left) is one of the few people who remain by Jackie’s (Edie Falco) side during her most troubled times on “Nurse 000208858R1 Jackie,” airing in its seventh and final season, Sundays at 8 p.m. on Showtime. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 26, 2015 — Sat., May 2, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 7 p.m. ESPN New York Mets at New WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 York Yankees (Live) Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Monday WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday 1 a.m. FOXSS Atlanta Braves at WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 1 p.m. ESPN2 O’Reilly Auto Parts Philadelphia Phillies (Replay) WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Springnationals from 1:30 a.m. -

Shameless, the Push-Pull of Transatlantic Fiction Format Adaptation, and Star Casting

Shameless, the push-pull of transatlantic fiction format adaptation, and star casting Article Accepted Version Knox, S. (2018) Shameless, the push-pull of transatlantic fiction format adaptation, and star casting. New Review of Film and Television Studies, 16 (3). pp. 295-323. ISSN 1740-7923 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2018.1487130 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/71997/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17400309.2018.1487130 Publisher: Taylor & Francis All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Shameless, the Push-Pull of Transatlantic Fiction Format Adaptation, and Star Casting Simone Knox, University of Reading With a long history of transatlantic exchanges, recent years have seen a notable number of UK-to-USA format adaptations. Factually-based programming (including the Idol franchise) has generally been the most numerous, the most commercially successful and received the most sustained critical attention (e.g. Oren and Shahaf 2012). However, adaptations of fiction formats have met with increasing scholarly attention, and this article will build on this work, interested in the ways in which, as Jean K. Chalaby has noted, the adaptation process for scripted formats: cannot be as perfunctory as for other genres. -

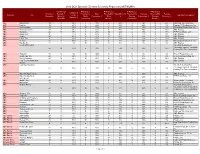

By % EPISODES DIRECTED by FEMALES & MINORITIES

2016 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by % EPISODES DIRECTED BY FEMALES & MINORITIES) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Male # Episodes Female Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Directed by Female Title Female + Caucasian Directed by Caucasian Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Minority % Female Female Minority % Minority % % Male Minority % Episodes Caucasian Caucasian Minority 11/22/63 9 0 0% 9 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% NS Pictures, Inc. Hulu Plus Almost There We're Out of Time DirecTV 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Productions Inc. Aquarius 13 0 0% 13 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Next Step Productions LLC NBC Ash vs. Evil Dead 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Starz Evil Productions, LLC Starz! Baby Daddy 20 0 0% 20 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Prodco, Inc. ABC Family Baskets 9 0 0% 9 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Louie Zach Productions, Inc. FX Benders 8 0 0% 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Blink TV, LLC IFC Berlin Station Paramount Overseas Epix 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Productions, Inc. Black Jesus 11 0 0% 11 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Triage Entertainment, LLC Cartoon Network Blunt Talk Right Here Right Now Starz! 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Productons, LLC Clipped Horizon Scripted Television TBS 9 0 0% 9 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Inc. CSI: Crime Scene CBS Broadcasting Inc. -

Leading the Way in Educating and Inspiring Visual Artists and Storytellers for More Than 45 Years

2018 leading the way in educating and inspiring visual artists and storytellers for more than 45 years THIS IS THE SUMMER TO COME TO MAINE. SEE WHAT’S NEW. PHOTO © NILS TCHEYAN We’re building more As I’ve watched the building grow, I think about all the ways that we are growing in creativity, craft, and community: than a dining pavilion • Our community of visual artists and storytellers reaches into more than 44 countries at the center of our across the globe. Our new website has been designed to help us stay connected longer and in more meaningful ways with this growing community of artists who campus. We’re building are changing the way we see the world through their stories in films, photos, and community. writing. • In 2018, new workshops and intensives will touch on filmmaking, photography, book A new pavilion was designed and gifted arts & design, and writing, and in ways that speak to the growing convergence by former board member and friend of between these forms of visual storytelling. the school, Brink Thorne, who wanted to • In film the 10-week-long cinematography intensive program includes an advisor to focus his gift on the heart of Maine Media provide continuity to the students while they benefit from experiencing the different where countless conversations, insights, styles of accomplished industry professionals each week. There’s a new Writing/ inspiration, and deep friendships begin. Directing Intensive, new comedy writing workshop, and so much more! • In photo we have so many of your favorite instructors returning, and we also have Maggie Taylor, Michael Christopher Brown, Xyza Cruz Bacani, Peter Krogh, Maggie Steber, and Brad Smith to name just a few of the outstanding new faculty that will be offering workshops in 2018. -

Showtime Offer

3/16/15 9:47 AM 9:47 3/16/15 1 460125-BI_Master.indd 3/23/15 1:40 PM 1:40 3/23/15 1 461418-BI_5210.indd NURSE JACKIE SHAMELESS RAY DONOVAN HOMELAND A SHOWTIME® Original Series A SHOWTIME® Original Series A SHOWTIME® Original Series A SHOWTIME® Original Series ©2015 Showtime Networks Inc. All rights reserved. SHOWTIME, THE MOVIE CHANNEL and related marks are trademarks of Showtime Networks Inc., a CBS Company. You must be a subscriber of Showtime to receive Showtime Anytime. Showtime Anytime is available through participating TV providers. Emmy® is a registered trademark of the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. “Happyish,” “Penny Dreadful” & “Ray Donovan”: ©Showtime Networks Inc. All rights reserved. “Homeland”: ©Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. All rights reserved. “Nurse Jackie”: ©Showtime Networks Inc. and Lions Gate Television, Inc. All rights reserved. “Shameless”: ©Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. All rights reserved. Stop Watching Cat Videos OK PENNY DREADFUL HAPPYISH BOYHOOD SHOWTIME CHAMPIONSHIP BOXING® A SHOWTIME® Original Series A New SHOWTIME® Original Series Hollywood Hits Showtime Sports® Get SHOWTIME® and THE START TM MOVIE CHANNEL WATCHING for only $8.95 per month for 12 months! • GET IT WHENEVER AND WHEREVER YOU WANT IT on your computer, tablet, mobile device and on your TV with SHOWTIME ANYTIME®, free with your subscription • With critically-acclaimed series, uncut hit movies, hard-hitting sports, Upgrade to a daring documentaries and outrageous comedy. • SHOWTIME® is the complete premium entertainment package. better breed of • Best of all, you’ll get SHOWTIME ON DEMAND® and THE MOVIE CHANNEL® ON DEMAND included FREE, for total control of the best in entertainment premium entertainment - on your schedule! Call 800-367-4882 www.gvtc.com Limited offer expires 07/31/15. -

Download Press

Does every relationship have an expiration date? GENERAL OVERVIEW 1 SYNOPSIS DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT BIOS – TEAM BIOS – TALENT LOCATIONS SCENE SHOOTS 2 PMA. Entertainment Marketing & PR Sell By is a romantic comedy about a group of friends navigating love, life, and relationships as they reach the mid-point. At the heart of the story is Adam (Scott Evans), a talented painter now stuck ghost painting for successful contemporary artist, Ravella Brewer (Patricia Clarkson). He and Marklin (Augustus Prew) are at the five-year mark of their relationship. They don't have kids, they're not married, and are face to face with the existential question “Is that all there is?” Their friend circle is confronting the same question in a whole host of ways: Elizabeth (Kate Walsh), Adam’s best friend, is at the 15 year mark of her marriage, ready to bail when she discovers her husband’s inappropriate text relationship with a younger woman; friend Cammy (Michelle Buteau) is dating Henry (Colin Donnell), but they never leave the house; Haley (Zoe Chao) is trying to figure out if her feelings for Scott James (Christopher Gray) are maternal or something more. Everyone’s a bit of a mess, but at the same time eternally optimistic at finding new ways to make things work. Sell By has heart, humor, and takes a very realistic look at romance -- fusing together the communal charm of a movie like The Big Chill unfolding in front of the gorgeous backdrop of New York City. www.pma.media 3 PMA. Entertainment Marketing & PR I am a child of divorce. -

2016 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By NETWORK)

2016 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by NETWORK) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Minority Directed by Female Directed by Female Network Title Female + Signatory Company Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A&E Bates Motel 10 3 30% 7 70% 2 20% 1 10% 0 0% Universal Television LLC A&E Damien 10 5 50% 5 50% 3 30% 2 20% 0 0% Damien TV Productions, Inc. A&E Unforgettable 13 3 23% 10 77% 1 8% 2 15% 0 0% Woodridge Productions, Inc. ABC American Crime 10 9 90% 1 10% 4 40% 4 40% 1 10% ABC Studios ABC Black-ish 24 18 75% 6 25% 10 42% 4 17% 4 17% FTP Productions, LLC ABC Blood & Oil 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0% ABC Studios ABC Castle 22 5 23% 17 77% 0 0% 1 5% 4 18% ABC Studios ABC Catch, The 9 3 33% 6 67% 1 11% 1 11% 1 11% ABC Studios ABC Dr. Ken 21 7 33% 14 67% 5 24% 2 10% 0 0% Woodridge Productions, Inc. ABC Family, The 11 1 9% 10 91% 0 0% 1 9% 0 0% ABC Studios ABC Fresh Off the Boat Twentieth Century Fox Television, a unit of Twentieth 24 15 63% 9 38% 3 13% 9 38% 3 13% Century Fox Film Corporation ABC Galavant 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Film 49 Productions, Inc.