ADOPTION HISTORY CROYDON.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of Great Bentley Patient Participation Group

Minutes of Great Bentley Patient Participation Group Thursday 20th March 2014 Chaired by – Melvyn Cox Present: Charles Brown – Vice Chairman Sharon Batson – Secretary Dr Freda Bhatti – Senior Partner Richard Miller – Practice Manager Approx 50 members present 1. Welcome and Apologies Melvyn Welcomed those present including Dr Shane Gordon Apologies received from Barry Spake 2. Minutes of Last Meeting Agreed 3.Guest Speak – Dr Shane Gordon, GP and Chief Officer, Clinical Commissioning Group The CCG has been in place since April 2013 and is the local NHS statutory body providing hospital and community services in our area, but does not cover general practice as this is provided by NHS England. Big Care Debate – looking at the future of the health service in the Colchester/Tendring areas. 1000 people have been involved in the last 4 months. The main topics are to look at changing the way NHS listens to the people it serves and being more available, and to make local general practice responsible for health services commissioned in the area. Circumstances we find ourselves in 2014 – The Health Service is very protected with regards to funding, services not needed to be slashed as drastically as within Social Services. However the growth in funding is not as fast as the growth in need. More people not working and paying tax, the older you get more medical conditions are likely and therefore costs more money. £400 million allocated to Colchester/Tendring CCG per annum £200 million allocated to NHS England for the area per annum. Under pressure to do more with the same money, £20 million more work in new year with the same money as last year. -

Cultural Sites and Constable Country a HA NROAD PE Z E LTO D R T M ROLEA CLO E O

Colchester Town Centre U C E L L O V ST FI K E N IN T R EMPLEW B T ı O R O BO D Cultural sites and Constable Country A HA NROAD PE Z E LTO D R T M ROLEA CLO E O S A T E 4 HE A D 3 CA D 1 D D P R A U HA O A E RO N D A RIAG S Z D O MAR E F OO WILSON W EL IE NW R A TO LD ROAD R EWS Y N R OD CH U BLOYES MC H D L R A BRO C D O R A I OA B D R A E LAN N D N D D R S O WA ROA W D MASON WAY T HURNWO O S S Y O I C A Y N P D TW A133 A I R S D A RD E G N E Colchester and Dedham routes W E CO L O R F VENU W A V R A F AY A AL IN B Parson’s COWDR DR N ENT G R LO C IN O Y A133 A DS ES A D A A Y WAY Heath Sheepen VE T A DR G A K C V OR NK TINE WALK 2 E IV K E D E BA N H IS Bridge NE PME IN I N 3 ON D I L A O R N P G R N C S E ER G G U R S O D E G L S 12 N N UM C MEADOW RD E N B H O IG A R R E E A O OA U U E RS E L C L EN A DI S D V R D R L A A A W D D B E D B K T R G D OA A A C I R L N A D R A 1 G B N ST Y T E D T D O R E 3 Y O A O A E O SPORTSWA A N R O L 4 D HE N U REET M W R R IR O V C AR CO EST FA RD R N T M H E D W G I A P S D C A C H R T T Y I V E ON D BA A E T R IL W E S O N O A B R E RO S T D RI W O M R A D R I O E T R N G C HA L I T STO ROAD U W A AU D E M I C UILDFOR R W G D N O A R SHEE C H ASE O BRIS L RO A E N T D PEN A A O S V A R O P OA D E 7 YC RU A D Y 3 W R C N 1 S E O S RD A RC ELL G D T ) A ES W R S TER S LO PAS D R N H S D G W O BY H E GC ENUE ER E U AV EST EP R RO ORY R E I D E K N N L F Colchester P AT N T IC ra L D R U H Remb S D N e ofnce DLEBOROUGH F E Institute ID H O V M ET LB RE E R A C R'SST C R IFER TE E N L E F D H O H ST -

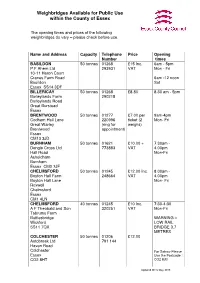

Weighbridges Available for Public Use Within the County of Essex

Weighbridges Available for Public Use within the County of Essex The opening times and prices of the following weighbridges do vary – please check before use. Name and Address Capacity Telephone Price Opening Number times BASILDON 50 tonnes 01268 £15 Inc. 6am - 5pm P.F Ahern Ltd 293931 VAT Mon - Fri 10-11 Heron Court Cranes Farm Road 6am -12 noon Basildon Sat Essex SS14 3DF BILLERICAY 50 tonnes 01268 £8.80 8.30 am - 5pm Barleylands Farm 290218 Barleylands Road Great Burstead Essex BRENTWOOD 50 tonnes 01277 £7.00 per 9am-4pm Codham Hall Lane 220996 ticket (2 Mon- Fri Great Warley (ring for weighs) Brentwood appointment) Essex CM13 3JD BURNHAM 50 tonnes 01621 £10.00 + 7.30am - Dengie Crops Ltd 773883 VAT 4.00pm Hall Road Mon-Fri Asheldham Burnham Essex CM0 7JF CHELMSFORD 50 tonnes 01245 £12.00 Inc. 8.00am - Boyton Hall Farm 248664 VAT 4.00pm Boyton Hall Lane Mon- Fri Roxwell Chelmsford Essex CM1 4LN CHELMSFORD 40 tonnes 01245 £10 Inc. 7:30-4:30 A F Theobald and Son 320251 VAT Mon-Fri Tabrums Farm Battlesbridge WARNING – Wickford LOW RAIL SS11 7QX BRIDGE 3.7 METRES COLCHESTER 50 tonnes 01206 £12.00 Autobreak Ltd 791 144 Haven Road Colchester For Satnav Please Essex Use the Postcode : CO2 8HT CO2 8JB Updated MCS May 2016 GREAT BENTLEY 50 tonnes 01206 £16.66 + 7:00am – George Wright Farms 252044 VAT 4.00pm Admirals Farm Office Mon – Fri Heckfords Road Great Bentley Weekends by Essex arrangement C07 8RS HARWICH 50 tonnes 01255 £18.50 24 hours Harwich International 252125 +VAT Port Ltd Station Road Parkeston Quay Harwich Essex CO12 4SR KELVEDON HATCH 50 tonnes 01277 £6.50 Inc. -

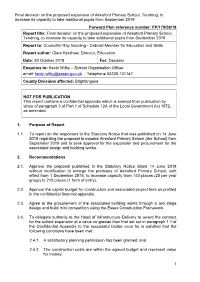

Final Decision on the Proposed Expansion of Alresford Primary

Final decision on the proposed expansion of Alresford Primary School, Tendring, to increase its capacity to take additional pupils from September 2019 Forward Plan reference number: FP/179/06/18 Report title: Final decision on the proposed expansion of Alresford Primary School, Tendring, to increase its capacity to take additional pupils from September 2019 Report to: Councillor Ray Gooding - Cabinet Member for Education and Skills Report author: Clare Kershaw, Director, Education Date: 30 October 2018 For: Decision Enquiries to: Kevin Wilby – School Organisation Officer email: [email protected] - Telephone 03330 131147 County Divisions affected: Brightlingsea NOT FOR PUBLICATION This report contains a confidential appendix which is exempt from publication by virtue of paragraph 3 of Part 1 of Schedule 12A of the Local Government Act 1972, as amended. 1. Purpose of Report 1.1. To report on the responses to the Statutory Notice that was published on 14 June 2018 regarding the proposal to expand Alresford Primary School (the School) from September 2019 and to seek approval for the expansion and procurement for the associated design and building works. 2. Recommendations 2.1. Approve the proposal published in the Statutory Notice dated 14 June 2018 without modification to enlarge the premises of Alresford Primary School, with effect from 1 September 2019, to increase capacity from 140 places (20 per year group) to 210 places (1 form of entry). 2.2. Approve the capital budget for construction and associated project fees as profiled in the confidential financial appendix. 2.3. Agree to the procurement of the associated building works through a two stage design and build mini competition using the Essex Construction Framework. -

Dedham St. Mary the Virgin Marriages 1813-1837 (Grooms)

Dedham St. Mary the Virgin marriages 1813-1837 (grooms) Groom surname Groom 1st Status Bride 1st Bride surname Status Date Notes Reg Banns. Bride & Wit.2 (Hannah Tuke) mark others ABBOTT Joseph bachelor Mary TUKE spinster 25 Dec 1821 sign. Witness 1: David Fish 75 Licence all sign. Witnesses: Joseph Wardle, Catherine Thomas Hanrietta Bishop, Elizabeth Borthwick, M Sophia Warde, ALKIN Turner Mary Anne WARDE 16 Feb 1836 Charlotte Augusta Backley?, H A Seale? 220 Banns. Groom abode: Ardleigh. Bride & groom mark ALLEN George Mary GARWOOD 01 Nov 1833 others sign. Wits: Osyth Shout, Benjm Cole 198 Licence all sign. Witnesses: Mahala Bruce, Henry AMBROSE John Robert Eunice BRUCE 09 Oct 1829 Powell 152 Banns. Witness 1 (Maria Folkard) marks others sign. APPLEBY William bachelor Elizabeth PARKER spinster 15 Oct 1819 Witness 2 & 3: Joseph Blyth, Thos Barker 50 APPLEBY William bachelor Mary COLE spinster 08 Oct 1820 Banns all mark. Witnesses: Benjamin & Hannah Cole 59 Banns. Bride & groom mark others sign. Bride abode: APPLEBY Thomas Susan PEGGS 22 Jan 1830 Great Bentley. Witnesses: Lydia Reece, Benjm. Cole 156 Banns. Groom abode: Walton le Soken. Bride marks others sign. Wits: Thomas Turner?, Mary Turner, ATKINS William Lucy TURNER 09 Jun 1835 Thomas Cole 211 Banns. Groom abode: Thorrington. Bride & Wit.1 (Susan Rolph) mark others sign. Witness 2: Adam BACON John widower Hannah SCOTT spinster 24 Oct 1824 Harvey Scott 97 Banns all sign. Groom abode: Ardleigh. Witnesses: BACON William Mary BARKER 08 Nov 1825 Amelia Belstead, Thos Barker 114 Banns. Groom abode: Messing. Bride & groom mark BACON John Sarah BIRD 10 Jan 1826 others sign. -

Willow Tree House, Thorrington Road, Great Bentley, Colchester

Willow Tree House, Thorrington Road, Great Bentley, Colchester, CO7 8QD Asking Price Of £750,000 A fantastic opportunity has arisen to acquire a rare to market five bedroom, four bathroom, four reception room detached house with no onward chain, stunning views, a kitchen/breakfast room, separate utility room, study, double garage as well off street parking for several vehicles in the sought after location of Great Bentley. THE PROPERTY Willow Tree House offers stunning views over the local countryside as well as being conveniently located for the local amenities of Great Bentley. This impressive detached five bedroom house is presented in immaculate condition and is offered to the market with the added attraction of having no onward chain. It is set back from the road allowing ample parking for several vehicles as well as having a detached double garage. On entering the property you will be greeted by a generous entrance hallway. Immediately to the left is the dining room big enough to accommodate a minimum of twelve guests whatever the occasion might be. The large living room with feature fire place where the present owners often relax and entertain is light and airy as well as having lovely views and access via doors onto the private partly decked/lawned garden. To the side of the living room is another spacious reception room also with direct access to the garden and raised decked terrace, which can be closed off if so desired by double doors, currently used as a games rooms with pool table, sofa and two "playseat" fully functional driving stations. -

The Evolution of Puritan Mentality in an Essex Cloth Town: Dedham and the Stour Valley, 1560-1640

The Evolution of Puritan Mentality in an Essex Cloth Town: Dedham and the Stour Valley, 1560-1640 A.R. Pennie Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Research conducted in the Department of History. Submitted: November, 1989. bs. 1 The Evolution of Puritan Mentality in an Essex Cloth Town: Dedham and the Stour Valley, 1560-1640 A.R. Pennie Summary of thesis The subject of this thesis is the impact of religious reformation on the inhabitants of a small urban centre, with some reference to the experience of nearby settle- ments. Dedham has a place in national history as a centre of the Elizabethan Puritan Movement but the records of the Dedham Conference (the local manifestation of that movement), also illustrate the development of Reformed religion in Dedham and associated parishes. The contents of the thesis may be divided into four sections. The first of these concerns the material life of the inhabitants of Dedham and the way in which this generated both the potential for social cohesion and the possibility of social conflict. The second section examines the attempt at parish reformation sponsored by the ministers associated with the Dedham Conference and the militant and exclusive doctrine of the Christian life elaborated by the succeeding generation of preachers. The third element of the thesis focuses on the way in which the inhabitants articulated the expression of a Reformed or Puritan piety and, on occasion, the rejection of features of that piety. The ways in which the townspeople promoted the education of their children, the relief of the poor and the acknowledgement of ties of kinship and friendship, have been examined in terms of their relationship to a collective mentality characterized by a strong commitment to 'godly' religion. -

Colchester and Dedham Area Centres Throughout the County

Colchester Its gentle agricultural landscape dotted with 5. Hollytrees Museum 12. Dedham Art & Craft Centre For many years Colchester has celebrated church towers and mills features strongly in the Three centuries of fascinating toys, costume The centre is located in an imaginatively its status as Britain’s oldest recorded town - works of the 18th century artist and national and decorative arts displayed in an attractive converted church in the heart of ‘Constable documented since it was the Celtic stronghold favourite John Constable. Colchester’s Georgian town house from 1718. Parkland, Country’. Three floors housing resident artists, of Camulodunum. Today it is a place range of attractions and places to visit are children’s play area, shop and sensory garden. ceramics, candle shop, jewellery maker, toy which offers a happy blend of heritage of complemented by a great range of places to Tel: 01206 282940 museum. A vast array of beautifully crafted items international importance together with a strong stay as you’ll need a few days to explore it fully. www.colchestermuseums.org.uk including furniture, paintings and prints, interior contemporary atmosphere including small designer and furniture restorer can be found specialist shops, cafés, restaurants and galleries. Attractions along the route: 6. Tymperleys Clock Museum there. On-site is also a whole food vegetarian The picture postcard castle, built by the 1. Colchester Castle Museum & Castle Park Enjoy this beautiful 15th century timber-framed restaurant serving delicious home-made fayre. Normans on top of the Roman Temple of The largest Norman keep in Europe. Superb house, once home of William Gilberd, scientist Tel: 01206 322666 Claudius so despised by Queen Boudica in Roman displays, hands-on activities and tours. -

Alresford Parish Council

Alresford Parish Council Alresford Neighbourhood Plan 2018-2033 Submission (Regulation 16) Consultation Version March 2020 Alresford Neighbourhood Plan Submission (Regulation 16) Consultation Version CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 Purpose of the plan ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 Policy context .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Monitoring the Plan ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 2 LOCAL CONTEXT .................................................................................................. 5 History of Alresford ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Profile of the community today ................................................................................................................................. 6 Main infrastructure issues in Alresford ................................................................................................................. 10 3 VISION AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................. -

Cycle Route 2

Cycle Tendring 2 Great Bicycle rides around the Brightlingsea and Manningtree area Cycle Tendring Why not discover and explore the beauty of the Tendring Peninsula by bike? There’s nothing like following the beautiful coastline or taking in the picturesque villages and countryside en-route. You’ll find the ideal setting for a family cycle ride or a more challenging route for the independent rider. Cycle Tendring 52 miles Tendring Bicycle ride around Manningtree, Harwich, Frinton, Walton, Clacton, Great Bentley and Brightlingsea Distance: 52 miles. 18. Go over the railway crossing and turn left at the roundabout (31.6 miles). Route: Starts from Manningtree, finishing in Brightlingsea. 19. Continue on this road, passing two mini roundabouts. At the third mini roundabout (32.8 miles) turn left on Start: Manningtree Sports Centre, Colchester Road, Lawford CO11 2BN. Parking is available. the B1032 to Clacton. At the next mini roundabout turn right (34 miles). Finish: Brightlingsea Sports Centre, Church Road CO7 0QL. Parking is available. 20. Keep ahead to a grass triangle, turning left onto Sladburys Lane. Follow this to a T Junction (37 miles) then Route details: turn right towards Clacton along Holland Road. 1. From Manningtree Sports Centre turn left then at the bottom of the hill (0.5 miles) turn right to ride along 21. When you reach Vista Road (38 miles) turn left towards the seafront and at the end of the road turn right. Manningtree High Street. Continue ahead, passing Mistley Towers (1.25 miles). 22. With the sea on your left head towards Clacton Pier, crossing the traffic lights and immediately turning left to 2. -

Land West of Heckford's Road Great Bentley Colchester Essex

Land west of Heckford’s Road Great Bentley Colchester Essex Archaeological Evaluation for Welbeck Strategic Land II LLP CA Project: 660840 Essex Site Code: GBEHR17 April 2017 LAND WEST OF HECKFORD’S ROAD GREAT BENTLEY COLCHESTER ESSEX Archaeological Evaluation CA Project: 660840 CA Report: 17132 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved revision by 25/04/17 TL SRJ QA MLC This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology Land west of Heckford’s Road, Great Bentley, Colcheester, Essex: Archaeological Evaluation CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 2 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 4 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................ 6 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 8 4. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 8 5. EVALUATION RESULTS (FIGS 2-9) ................................................................. 9 6. THE FINDS ....................................................................................................... -

ESSEX. [ KELLY's Farmers-Continued

614 FAR ESSEX. [ KELLY'S FARMERs-continued. Colyer John, Good Easter, Ohelmsford Craig Allan, Arden hall, Horndon-on- Olarke George, Purleigh, Maldon Oook J. Ga1leywood corn. Chelmsford the-Hill, Grays Olarke H. White's pI. Margaretting, Oook William E. Martin's farm, Hut- Oraig Andrew, Greenacre farm, Stock, Ingatestone RS.O ton, Brentwood Ingatestone RS.O Clarke J.Flowers hall,Toppesfld.Halstd Cooper OharIes, Broad ditch, Bad- Craig Hugh, Lower park, Havering- Clarke James, South Shoebury hall, winter, Saffron WaIden atte-Bower, Romford Shoeburyness S.O Oooper Edgar, Little Bromley hall & Craig Hugh, Paslow hall, High Ongar, Clarke Nathaniel, Lodge farm, Up- Mulley's farms, Little Bromley hall, Ongar 8.0 per Dovercourt, Harwich Manningtree Craig James, sen. Barnard's farm, Clarke R.Ashen, Glare R.S.O.(Snffolk) Cooper F. Block's farm, Hatfield,Harlw East Horndon, Brentwood Olarke W. B. Tye fm. Peldon, Colchstr Cooper Frederick, Ashen, Clare R.S.O..Oraig James, Fitzjohn's, Halstead Clarkll William, Bridge foot, Great (Suffolk) & Ashen Hall & Highfield Cr'lig James, jun. Little Tilling-ham East~n, Dunmow hall, Tilbury hall, Childerditch, Brentwood Clay Edwin,Littlebury, Saffron Waldn Cooper G. F. Heath, Hatfield, Harlow Craig Robert, Crondon. park, Stock, Olayden Oharles, PentoD hall, Manu- Cooper Henry 1Villiam, Folly farm, Ingatestone R.S.O den, Stansted R.S.O London road, Leigh S.O Craig Thomas, Toppesfield, Halstead Clayden Harry,Parsonage farm, Steeple Oooper Robert, Hockley S.O Oraig William, Toppesfield, Halstead Bumpstood, Have.rhill Oooper Sidney (poultry), Rettendon Orane James &; James WilIiam, Old Clayden John, Free Roberts, Great common, Chelmsford England, Little Warley, Brentwood Sampford, Braintree Oooper William, Malting green, Great Crane J ames, Bollen's, Great ""VarIey, G'laydenW.Breach Barnes,Wlthm.Abby Oakley, Harwich Brentwood Clayden William, Maynard's farm, Cooper William Percy, South heath, Crane Samuel, .A.rnold's farm, Lam- Waltham Abbey Great Bentley, Colchester bourne, Romford Claydon George, Ludham hall, Black Coote James W.