Statelessness and Marginalisation in Assam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village & Town Directory Primary Census Abstract, Part X-A-, X-B

CENSUS -1 971 SERIES-3 ASSAM PART X-A VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY PART X-B PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK KAMRUP A. K. SAlKlA of the Indian Administ,rative Service DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, ASSAM Cover motif represents the Kamakhya temple' situated on the Nilachal HilJ of Kamrup District. Printed at the Sreegufu Press, Maligaon, Gauhati-ll and Published by the Government of Assam. ASSAM DISTRICT KAMRUP i. RF. i'25~OOO H u T A N o y A N 0 ~ G' 0 .f'i o Cl \ 'i" REFERENCES ~ DlmICTHE"OQu~ms ..• @ @ ~ TH,lNA Name of the lHmNAnONALBOI!MDA~r Thana sun 8.1,GIIBOR 6500 OISTRI~T BARPETA 769·2 TH.I,HA B"~AMA \. SOKO SUB'DIVISIONAL CHHAYGAO/l 450·7 HAfiOHAL ~IGHWAYS GAUHATI 7692 STAn HIGHWAYS ~ 1 ... ....!!L. HAjO 68 1·2 MHALLEDROAOS I JHAlUKe.l,~ 1 389 u~MmLLEDROADS 1t ... Irt1AlPUR 4222 177 t.1 ,G_RAILW.Io.YS WITH STATIONS 515 '4 432 POSia:THHiRAPH OffiCES P&T 6190 198 RmHOUSE /TRAV[llE I1SeU~GAtOW\HC .• , RM G '" '''LA~8'''RI ,n, 20b I e R"'NGIA 510·2 184 MARK£TS Gl SO R8110" 9687 256 MANIIIES IA M E TA~AeAAI 3004 73 ItO~PIUUf~.H,C,I!llsf'!W~~I'UC,W,CtHT!lf5 @: A W~ 0 I(S THE AR[A, FIGURES SUPPlltD er TH£ HMULPUR 769·2 211 Ilv", ~ SURVEYOR amAl OF INDIA *DEMHS aE APEAF ICUR ESSuPPLlEOBYTH~ 9.9560 ).)44 17 I' TOTAL ~ --« DIRECTOR OF LAND RECORDS, AS>AM 9.86} 'I TOWNS • CONTENTS Pa~es PREFACE iii FIGURES AT A GLANCE iv NOTE VOx Village Directory (vJ Town Directory (v-vi) Primary Census Abstract (vi-x) PART X-A VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE DIRECTORY 1-247 Key to the Codes used for the entries in the Village Directory (3)-Police Station wise Abstract of Educational,Medical and other Amenities (4-5)-Baghbor P. -

NRC Face Off in Assam

NRC face off in Assam First draft of National Register of Citizens (NRC) The much-awaited first draft of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was published with the names of 1.9 crore people out of the 3.29 crore total applicants in Assam recognizing them as legal citizens of India. What is NRC (National Register of Citizens)? The National Register of Citizens (NRC) contains names of Indian citizens. The NRC was prepared in 1951 by recording particulars of all the persons enumerated during that Census. Why is NRC currently in news? The NRC updation is currently going on across Assam and shall include the names of those persons (or their descendants) who appear in the NRC 1951, or in any of the Electoral Rolls up to the midnight of 24 March 1971 or in any one of the other admissible documents issued up to the midnight of 24 March 1971, which would prove their presence in Assam on or before 24 March 1971. The NRC (1951) and the Electoral Rolls up to the midnight of 24 March 1971 together are collectively called Legacy Data. How many states have its NCR’s? Assam is the only state to have its own register of citizens Why was it necessary to bring out an NRC in Assam? The NRC is being updated in Assam to detect Bangladeshi nationals, who may have illegally entered the State after the midnight of March 24, 1971, the cut-off date. This date was originally agreed to in the 1985 Assam Accord, signed between the then Rajiv Gandhi government and the All Assam Students Union (AASU). -

Guwahati Development

Editorial Board Advisers: Hrishikesh Goswami, Media Adviser to the Chief Minister, Assam V.K. Pipersenia, IAS, Chief Secretary, Assam Members: L.S. Changsan, IAS, Principal Secretary to the Government of Assam, Home & Political, I&PR, etc. Rajib Prakash Baruah, ACS, Additional Secretary to the Government of Assam, I&PR, etc. Ranjit Gogoi, Director, Information and Public Relations Pranjit Hazarika, Deputy Director, Information and Public Relations Manijyoti Baruah, Sr. Planning and Research Officer, Transformation & Development Department Z.A. Tapadar, Liaison Officer, Directorate of Information and Public Relations Neena Baruah, District Information and Public Relations Officer, Golaghat Antara P.P. Bhattacharjee, PRO, Industries & Commerce Syeda Hasnahana, Liaison Officer, Directorate of Information and Public Relations Photographs: DIPR Assam, UB Photos First Published in Assam, India in 2017 by Government of Assam © Department of Information and Public Relations and Department of Transformation & Development, Government of Assam. All Rights Reserved. Design: Exclusive Advertising Pvt. Ltd., Guwahati Printed at: Assam Government Press 4 First year in service to the people: Dedicated for a vibrant, progressive and resurgent Assam In a democracy, the people's mandate is supreme. A year ago when the people of Assam reposed their faith in us, we were fully conscious of the responsibility placed on us. We acknowledged that our actions must stand up to the people’s expectations and our promise to steer the state to greater heights. Since the formation of the new State Government, we have been striving to bring positive changes in the state's economy and social landscape. Now, on the completion of a year, it makes me feel satisfied that Assam is on a resurgent growth track on all fronts. -

Director's Report

DIRECTOR'S REPORT First Convocation 19th M ay, 1999. Hon ' ble Govern or of Assam and Chairman of the Board of Governors of liT Guwahati, Gen. S.K. Sin ha, Hon' ble Chi ef Minister of Assam, Shri Prafu ll a Kumar Mahanta, Members of the Board of Governors, Members of the Senate, grad uating students, ladies and gentlemen: It gives me great pleasure to extend a very warm welcome to all of you on the occasion of the very first convocation of the Ind ian Institute of Technology, Guwahati. It is our privil ege on this hi storic occasio n to have amidst us the Hon' ble Chief Minister of Assam, Shri Mahanta, who, as the then President of the All Assam Students' Un ion in 1985, was one of the architects of the Assam Accord and was instrumental in paving the way for settin g up of a sixth liT in Assam as a part of that Accord. We therefore extend a very special welc ome to you, Sir, and look forward to hearing yo ur Convocation address. It is my pleasant duty now to present to you a rep0\1 of the acti vities of thi s Institute fro m the time of its establ ishment till now. I would like to begin the report with the genesis of th is Institute. GENESIS The Assam Accord signed in August 1985 by the then Prime Mi nister, Sri Raji v Gandh i, and the student leaders of the A ll Assam Students Unio n, stipulated among other clauses, that an IlT be set up in the State of Assam. -

THE DYNAMICS of the DEMOBILIZATION of the PROTEST CAMPAIGN in ASSAM Tijen Demirel-Pegg Indiana University-Purdue University Indi

THE DYNAMICS OF THE DEMOBILIZATION OF THE PROTEST CAMPAIGN IN ASSAM Tijen Demirel-Pegg Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Abstract: This study highlights the role that critical events play in the demobilization of protest campaigns. Social movement scholars suggest that protest campaigns demobilize as a consequence of polarization within the campaign or the cooptation of the campaign leaders. I offer critical events as an alternative causal mechanism and argue that protest campaigns in ethnically divided societies are particularly combustible as they have the potential to trigger unintended or unorchestrated communal violence. When such violence occurs, elite strategies change, mass support declines and the campaign demobilizes. An empirical investigation of the dynamics of the demobilization phase of the anti-foreigner protest campaign in Assam, India between 1979 and 1985 confirms this argument. A single group analysis is conducted to compare the dynamics of the campaign before and after the communal violence by using time series event data collected from The Indian Express, a national newspaper. The study has wider implications for the literature on collective action as it illuminates the dynamic and complex nature of protest campaigns. International Interactions This is the author's manuscript of the article to be published in final edited form at: Demirel-Pegg, Tijen (2016), “The Dynamics of the Demobilization of the Protest Campaign in Assam,” International Interactions. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03050629.2016.1128430 Introduction The year 2014 was marked by intense protests against the police after the killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Eric Garner in New York and the subsequent failure to indict the police officers that killed them. -

English Speech 2020 (Today).Pmd

1. Speaker Sir, I stand before this August House today to present my fifth and final budget as Finance Minister of this Government led by Hon’ble Chief Minister Shri Sarbananda Sonowal. With the presentation of this Budget, I am joining the illustrious list of all such full-time Finance Ministers who had the good fortune of presenting five budgets continuously. From the Financial Year 1952-53 up to 1956-57, Shri Motiram Bora, from 1959-60 to 1965-66, former president of India Shri Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed in his capacity as Finance Minister of Assam, and then Shri Kamakhya Prasad Tripathi from 1967-68 to 1971-72 presented budgets for five or more consecutive years before this August House. Of course, as and when the Chief Ministers have held additional responsibility as Finance Minister, they have presented the budget continuously for five or more years. This achievement has been made possible only because of the faith reposed in me by the Hon’ble Chief Minister, Shri Sarbananda Sonowal and by the people of Assam. I also thank the Almighty for bestowing upon me this great privilege. This also gives us an opportune moment to now digitise all the budget speeches presented before this August House starting from the first budget laid by Maulavi Saiyd Sir Muhammad Saadulla on 3rd August 1937. 2. Hon’ble Speaker Sir, on May 24, 2016, a new era dawned in Assam; an era of hope, of aspiration, of development and of a promise of a future that embraces everyone. Today, I stand before you in all humility, to proudly state that we have done our utmost to keep that promise. -

1.How Many People Died in the Earthquake in Lisbon, Portugal? A

www.sarkariresults.io 1.How many people died in the earthquake in Lisbon, Portugal? A. 40,000 B. 100,000 C. 50,000 D. 500,000 2. When was Congress of Vienna opened? A. 1814 B. 1817 C. 1805 D. 1810 3. Which country was defeated in the Napoleonic Wars? A. Germany B. Italy C. Belgium D. France 4. When was the Vaccine for diphtheria founded? A. 1928 B. 1840 C. 1894 D. 1968 5. When did scientists detect evidence of light from the universe’s first stars? A. 2012 B. 2017 C. 1896 D. 1926 6. India will export excess ___________? A. urad dal B. moong dal C. wheat D. rice 7. BJP will kick off it’s 75-day ‘Parivartan Yatra‘ in? A. Karnataka B. Himachal Pradesh C. Gujrat D. Punjab 8. Which Indian Footwear company opened it’s IPO for public subscription? A. Paragon B. Lancer C. Khadim’s D. Bata Note: The Information Provided here is only for reference. It May vary the Original. www.sarkariresults.io 9. Who was appointed as the Consul General of Korea? A. Narayan Murthy B. Suresh Chukkapalli C. Aziz Premji D. Prashanth Iyer 10. Vikas Seth was appointed as the CEO of? A. LIC of India B. Birla Sun Life Insurance C. Bharathi AXA Life Insurance D. HDFC 11. Who is the Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh? A. Babulal gaur B. Shivraj Singh Chouhan C. Digvijaya Singh D. Uma Bharati 12. Who is the Railway Minister of India? A. Piyush Goyal B. Dr. Harshvardhan C. Suresh Prabhu D. Ananth Kumar Hegade 13. -

Shakti Vahini 307, Indraprastha Colony, Sector- 30-33, Faridabad, Haryana Phone: 95129-2254964, Fax: 95129-2258665 E Mail: [email protected]

Female Foeticide, Coerced Marriage & Bonded Labour in Haryana and Punjab; A Situational Report. (Released on International Human Rights Day 10th of Dec. 2003) Report Prepared & Compiled by – Kamal Kumar Pandey Field Work – Rishi Kant shakti vahini 307, Indraprastha colony, Sector- 30-33, Faridabad, Haryana Phone: 95129-2254964, Fax: 95129-2258665 E Mail: [email protected] 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report is a small attempt to highlight the sufferings and plights of the numerous innocent victims of Human Trafficking, with especial focus on trades of bride in the states of Haryana and Punjab. The report deals with the problem and throws light on how the absence of effective definition and law, to deal with trade in ‘Human Misery’ is proving handicap in protecting the Constitutional and Human Rights of the individuals and that the already marginalised sections of the society are the most affected. The report is a clear indication of how the unequal status of women in our society can lead to atrocities, exploitation & innumerable assault on her body, mind and soul, in each and every stage of their lives beginning from womb to helpless old age. The female foeticide in Haryana and Punjab; on one hand, if it is killing several innocent lives before they open the eyes on the other is causing serious gender imbalance which finally is devastating the lives of equally other who have been lucky enough to see this world. Like breeds the like, the evil of killing females in womb is giving rise to a chain of several other social evils of which the female gender is at the receiving end. -

Nmml Occasional Paper

NMML OCCASIONAL PAPER HISTORY AND SOCIETY New Series 78 Assam, Nehru, and the Creation of India’s Eastern Frontier, 1946–1950s Arupjyoti Saikia Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati Nehru Memorial Museum and Library 2015 NMML Occasional Paper © Arupjyoti Saikia, 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author. This Occasional Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the NMML. The views expressed in this Occasional Paper are those of the author(s) and speakers and do not represent those of the NMML or NMML policy, or NMML staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide support to the NMML Society nor are they endorsed by NMML. Occasional Papers describe research by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. Questions regarding the content of individual Occasional Papers should be directed to the authors. NMML will not be liable for any civil or criminal liability arising out of the statements made herein. Published by Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Teen Murti House New Delhi-110011 e-mail : [email protected] ISBN : 978-93-83650-88-0 Price Rs. 100/-; US $ 10 Page setting & Printed by : A.D. Print Studio, 1749 B/6, Govind Puri Extn. Kalkaji, New Delhi - 110019. E-mail : [email protected] NMML Occasional Paper Assam, Nehru, and the Creation of India’s Eastern Frontier, 1946–1950s* Arupjyoti Saikia The story of the making India’s eastern frontier has to begin by recounting the deep impact of World War II on the region. -

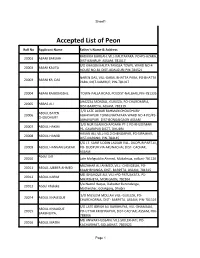

Accepted List of Peon

Sheet1 Accepted List of Peon Roll No Applicant Name Father's Name & Address RADHIKA BARUAH, VILL-KALITAPARA. PO+PS-AZARA, 20001 ABANI BARUAH DIST-KAMRUP, ASSAM, 781017 S/O KHAGEN KALITA TANGLA TOWN, WARD NO-4 20002 ABANI KALITA HOUSE NO-81 DIST-UDALGURI PIN-784521 NAREN DAS, VILL-GARAL BHATTA PARA, PO-BHATTA 20003 ABANI KR. DAS PARA, DIST-KAMRUP, PIN-781017 20004 ABANI RAJBONGSHI, TOWN-PALLA ROAD, PO/DIST-NALBARI, PIN-781335 AHAZZAL MONDAL, GUILEZA, PO-CHARCHARIA, 20005 ABBAS ALI DIST-BARPETA, ASSAM, 781319 S/O LATE AJIBAR RAHMAN CHOUDHURY ABDUL BATEN 20006 ABHAYAPURI TOWN,NAYAPARA WARD NO-4 PO/PS- CHOUDHURY ABHAYAPURI DIST-BONGAIGAON ASSAM S/O NUR ISLAM CHAPGARH PT-1 PO-KHUDIMARI 20007 ABDUL HAKIM PS- GAURIPUR DISTT- DHUBRI HASAN ALI, VILL-NO.2 CHENGAPAR, PO-SIPAJHAR, 20008 ABDUL HAMID DIST-DARANG, PIN-784145 S/O LT. SARIF UDDIN LASKAR VILL- DUDPUR PART-III, 20009 ABDUL HANNAN LASKAR PO- DUDPUR VIA ARUNACHAL DIST- CACHAR, ASSAM Abdul Jalil 20010 Late Mafiguddin Ahmed, Mukalmua, nalbari-781126 MUZAHAR ALI AHMED, VILL- CHENGELIA, PO- 20011 ABDUL JUBBER AHMED KALAHBHANGA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, 781315 MD ISHAHQUE ALI, VILL+PO-PATUAKATA, PS- 20012 ABDUL KARIM MIKIRBHETA, MORIGAON, 782104 S/o Nazrul Haque, Dabotter Barundanga, 20013 Abdul Khaleke Motherjhar, Golakgonj, Dhubri S/O MUSLEM MOLLAH VILL- GUILEZA, PO- 20014 ABDUL KHALEQUE CHARCHORRIA, DIST- BARPETA, ASSAM, PIN-781319 S/O LATE IDRISH ALI BARBHUIYA, VILL-DHAMALIA, ABDUL KHALIQUE 20015 PO-UTTAR KRISHNAPUR, DIST-CACHAR, ASSAM, PIN- BARBHUIYA, 788006 MD ANWAR HUSSAIN, VILL-SIOLEKHATI, PO- 20016 ABDUL MATIN KACHARIHAT, GOLAGHAT, 7865621 Page 1 Sheet1 KASHEM ULLA, VILL-SINDURAI PART II, PO-BELGURI, 20017 ABDUL MONNAF ALI PS-GOLAKGANJ, DIST-DHUBRI, 783334 S/O LATE ABDUL WAHAB VILL-BHATIPARA 20018 ABDUL MOZID PO&PS&DIST-GOALPARA ASSAM PIN-783101 ABDUL ROUF,VILL-GANDHINAGAR, PO+DIST- 20019 ABDUL RAHIZ BARPETA, 781301 Late Fizur Rahman Choudhury, vill- badripur, PO- 20020 Abdul Rashid choudhary Badripur, Pin-788009, Dist- Silchar MD. -

India May 2009

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT INDIA 12 MAY 2009 UK Border Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE INDIA 12 MAY 2009 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN INDIA FROM 17 MARCH 2009 – 12 MAY 2009 REPORTS ON INDIA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 17 MARCH 2009 AND 12 MAY 2009 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ......................................................................................... 1.01 Map ................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ............................................................................................. 2.01 3. HISTORY ............................................................................................... 3.01 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS....................................................................... 4.01 Elections ....................................................................................... 4.04 Mumbai terrorist attacks – November 2008 ............................... 4.08 5. CONSTITUTION ...................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM................................................................................ 6.01 Human Rights 7. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 7.01 UN Conventions ........................................................................... 7.05 8. SECURITY SITUATION ........................................................................... -

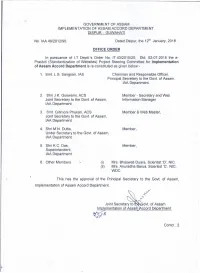

Government of Assam Implementation of Assam Accord Department

GOVERNMENT OF ASSAM IMPLEMENTATION OF ASSAM ACCORD DEPARTMENT. DISPUR :: GUWAHATI No. IAA 49/2012/90, Dated Dsipur, the 1ih January, 2018 . OFFICE ORDER In pursuance of LT DepU.'s Order No. IT.43/2015/20, Dtd. 02-07-2015 the e- Prastuti (Standardization of Websites) Project Steering Committee for Implementation of-Assam Accord Department is re-constituted as given below:- 1. Smt. L.S. Sangsan, IAS Chairman and Responsible Officer, Principal Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, IAA Department. 2. Shri J.K. Goswami, ACS Member - Secretary and Web Joint Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Information Manager IAA Department. 3. Smt. Gitimoni Phukan, ACS Member & Web Master, Joint Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, IAA Department. 4. Shri M.N. DuUa, Member, Under Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, IAA Department. 5. Shri K.C. Das, Member, Superintendent, IAA Department. 6. Other Members (i) Mrs. Bhaswati Duara, Scientist '0', NIC. (ii) Mrs. Anuradha Barua, Scientist 'C', NIC. WDC. This has the approval of the Principal Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Implementation of Assam Accord Department. Joint Secretary to t Im lementation of Assa Contd ... 2 -2- Memo No. IAA 49/2012/ 90-A Dated Dsipur, the 12th January,2018. Copy to: 1. P.S. to the Additional Chief Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Information Technology Department, Dispur for kind appraisal of the Additional Chief Secretary. 2. P.S. to the Principal Secretary to the Govt. of Assam, Implementation of Assam Accord Department, Dispur for kind appraisal of the Principal Secretary. 3. The Commissioner & Secretary to the Govt.