Experiments in Living Cells and Theoretical Work Have Implicated Energy-Consuming Patterning Mechanisms Located at the Cell 'S Edge, the Plasma Membrane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graduate and Professional Bulletin 2000 • 2003 U Niversity of Pittsburgh

TABLE OF CONTENTS University of Pittsburgh GRADUATE AND PROFESSIONAL BULLETIN 2000 • 2003 U NIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH USING THIS BULLETIN Students who are interested in or accepted to any of the University of Pittsburgh’s graduate or professional programs other than those leading to the first-professional degrees offered by the University (MD, JD, LLM, PharmD, or DMD) will find useful most of the sections of this bulletin. Descriptions of the University, its regulations, and its services are included in the sections prior to the program-specific information in the Schools, Departments, and Programs section of the bulletin. Students interested in first-professional programs (MD, JD, LLM, PharmD, or DMD) can ignore much of the bulletin prior to the First-Professional Programs section, but should familiarize themselves with the general information on the University, as well as the section on Campus Facilities & Student Services, and the University-wide policies detailed in Rights and Responsibilities. The Schools of Medicine, Law, Dental Medicine, and Pharmacy appear in the Schools, Departments, and Programs section for programs leading to the graduate and professional advanced degrees as well as in the First-Professional Programs section since these schools offer both types of programs. Faculty are listed by their department or program at the end of the school. Students should note that the listings of requirements and procedures for admissions, registration, and other information listed in the sections prior to the more program-specific information provided in the Schools, Departments, and Programs section of this bulletin represent the minimum requirements and basic procedures. Students should consult the information on their specific school, program, and department for detail on additional or stricter requirements and procedures. -

Prof. Satyajit Mayor Got Prestigious Chevalier De L'ordre National Du

Prof. Satyajit Mayor got prestigious Chevalier De L’ordre National Du Mérite Prof. Satyajit Mayor, Director of the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS-TIFR) was conferred the distinguished Chevalier de l’Ordre national du Mérite, French order of merit by the Ambassador of France to India, Mr. H. E. Emmanuel Lenain on 19th November, 2019. Prof. Satyajit Mayor with Mr. H. E. Emmanuel Lenain, the Ambassador of France to India, Prof. Mayor is professor and director of the National Centre for Biological Science (NCBS), Bangalore, and Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine (inStem), Bangalore, India. In 2012, Prof. Mayor won the Infosys Prize for life sciences for his research on regulated cell surface organization and membrane dynamics. He studied chemistry at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Bombay and has earned his Ph.D. in life sciences from The Rockefeller University, New York. He developed tools to study the trafficking of membrane lipids and GPI- anchored proteins in mammalian cells using quantitative fluorescence microscopy during his post-doctoral research at Columbia University. Prof. Mayor has to his credit some of the prestigious national and international awards. Few of the awards and fellowships include Foreign Associate to US National Academy of Sciences, EMBO Fellow, TWAS Prize in Biology, JC Bose Fellowship, CSIR-Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Award, Swarnajayanti Fellowship, Wellcome Trust International Senior Research Fellowship, Mizutani Foundation for Glycoscience Award, Helen Hays Whitney Post-Doctoral Fellowship, etc. The prestigious Chevalier de l’Ordre national du Mérite award reflects Prof. Mayor’s extensive efforts in supporting Indo-French scientific collaborations. -

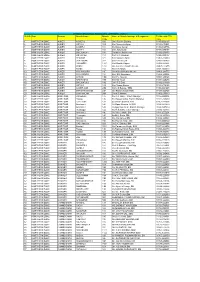

BO GRO LIST UPDATED 20-21-Without Email Id.Xlsx

BRANCH GRIEVANCE REDRESSAL OFFICERS : 2020-21 SL NO Zone Division Branch Name Branch Name of Branch Incharge & Designation Tel No. with STD Code code 1 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER AJMER-2 106 Shri Rajeev Sharma 0145-2662465 2 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KOTA-2 109 Shri Prameet billiyan 0744-2473051 3 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER AJMER-1 181 Sh. Manoj Kumar 0145-2429756 4 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KOTA-1 182 Shri Ajay Goyal 0744-2390457 5 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BHILWARA-1 198 Shri khem Raj Meena 01482-239838 6 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KOTA-CAB 313 Shri K C Mahavar 0744-2390797 7 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BEAWAR 321 Shri Kailash Chand 01462-225039 8 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER JHALAWAR 322 Shri B R Meena 07432-232433 9 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER LAKHAERI 1201 Shri Manish Kapoor 07438-261681 10 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KEKRI 1202 SH. Suresh Chandra Meena 01467-222475 11 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BUNDI 18A Shri V D Singh 0747-2456620 12 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KISHANGARH 18F Shri Kailash Kumar Meena 01463-246775 13 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER SHAHAPURA 18J Shri S K Srivastava 01482-223564 14 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BARAN 18M Shri P L Meena 07453-230165 15 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER NASIRABAD 18N Shri AD Tiwari 01491-220273 16 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BHILWARA-2 18U Shri R D Dad 01482-243199 17 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KOTA-3 18X Shri Pawan Kumar 0744-2472423 18 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER AJMER CAB 29N Shri J N Bairwa / SBM 0145-2664665 19 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BHAWANI MANDI 29P shri Rajesh Kumar Rathi 07433-222725 20 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BIJAYNAGAR 29R Shri K.S.Meena 01462-230149 21 NORTHERN ZONE AMRITSAR Pathankot-I 135 Sh. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta The Refugee Woman: Partition of Bengal, Women, and the Everyday of the Nation by Paulomi Chakraborty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Paulomi Chakraborty Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Dde18june21.Pdf

StudentId ROLLNO PROLLNO REGNO StudentName PAGE MName SUB1 SUB2 SUB3 SUB4 SUB5 SUB6 SUB7 174330 101010001 - 1025DDEJM20 BABLU SHARMA SHAM LAL SHARMA GEETA DEVI AA-101 ED-101 PY-101 GG-101 174331 101010002 - 1026DDEJM20 NITIN SHARMA ASHOK KUMAR ASHA DEVI AA-101 HT-101 SO-101 PS-101 174332 101010003 - 1027DDEJM20 AVNEET SINGH HARCHARAN SINGH RAVINDER KOUR AA-101 ED-101 PS-101 PU-101 174333 101010004 - 1028DDEJM20 TARUN SHARMA BHUSHAN LAL MAMTA DEVI AA-101 ED-101 SO-101 PS-101 174334 101010005 - 1029DDEJM20 KAMAL KUMAR VIJAY KUMAR JYOTI DEVI AA-101 ED-101 SO-101 PS-101 174464 101010006 - 1159DDEJM20 SHAID AHMED MOHD HAFIEEZ MANIZA BEGUM AA-101 ED-101 SO-101 GG-101 174466 101010007 - 1161DDEJM20 AJEET SINGH NARESH SINGH TRIPTA DEVI AA-101 ED-101 SO-101 PL-101 174468 101010008 - 1163DDEJM20 KAMALJEET KUMAR KALA RAM DARSHNA AA-101 ED-101 HT-101 HI-101 174469 101010009 - 1164DDEJM20 NAUSHAD AHMED AZAD MOHD RAZAQ AZMAT BI AA-101 HS-108 SO-101 PS-101 174470 101010010 - 1165DDEJM20 RAHUL KUMAR DARSHAN KUMAR ANITA DEVI AA-101 ED-101 PS-101 PL-101 174535 101010011 - 1230DDEJM20 KARTIK BHAN MAHRAJ KRISHAN BHAN PINKY BHAN AA-101 HT-101 SO-101 PS-101 174461 101010012 - 1156DDEJM20 PANKAJ SINGH CHARAK PARVEEN SINGH CHARAK JYOTI RANI AA-101 ED-101 SO-101 PS-101 174399 101010013 - 1094DDEJM20 SIDDHARATH SINGH BALI BAL KRISHAN BALI GIYAN DEVI AA-101 ED-101 HT-101 PS-101 174416 101010014 - 1111DDEJM20 ABHINASH SHARMA RAM LAL KAMLESH SHARMA AA-101 ED-101 PY-101 MA-101 174398 101010015 - 1093DDEJM20 BHUPINDER SINGH JASBIR SINGH TRIPTA DEVI AA-101 MA-101 PS-101 -

Praagaash April 2020.Cdr

For Private Circulation Only Net-journal of 'Project Zaan’ ÒççiççMç Praagaash Dedicated to Our Heritage, Our Language and Our Culture Magnificient Harmukh, Kashmir (Elevation 5142 M) Photo @katoch104 1567 Mtr below lies Gangabal Lake 2500 M Long, 1000 M Wide (Photos bottom left wordpress.com, bottom right Memorable India) ß vçcçççÆcç lJççb Mççjoç oíJççR, cçnçYççiççR YçiçJçlççR kçÀçMcççÇj hçájJçççÆmçvççR çÆJçÐçç oççƳçvççR j#ç cççcçd j#ç cççcçd~ vçcçççÆcç lJççcçd~ Jç<ç& 5 : DçbkçÀ 4~ DçÒçÌuç 2020 Vol 5 : No. 4~ April 2020 02 Praagaash ÒççiççMç `Òççípçíkçwì ]pççvç' kçÀçÇ vçíì-HççÆ$çkçÀç Jç<ç& 5 : DçbkçÀ 4 ~ DçÒçÌuç 2020 In this issue Editorial l Cover - Magnificient Harmukh & Gangabal Lake 01 l Editorial - M.K.Raina 02 We are encouraged to see the l JççKç lçe ÞçáKç 03 popularity of our Supplements with l Nadim Sahib : Onkar Aima the readers, first The Story of a - My Pleasant Rememberances 04 l Agha-Bai of Zoona Dab : Bashir Arif Bicycle (released with the - Last Moments of Marriyam Begum 07 February 2020 issue of l Encounter with Reality : Manzoor Nawchoo Praagaash) and then the Zoona - Sweet Dreams Turned Into Bitter Reality 08 Dab (released with the March l kçÀLç : yçMççÇj DçççÆjHçÀ - Yç´ä (vçmlççuççÇkçÀ) 13 Yç´ä (oíJçvççiçjçÇ) 2020 issue of Praagaash). Not 16 only that people have read it with l kçÀçJ³ç : Jçnçyç Kççj - pçç³ç kçÀl³ççí s³ç (vçmlççuççÇkçÀ) 19 pçç³ç kçÀl³ççí s³ç (oíJçvççiçjçÇ) 20 interest but have also encouraged l My Medical Journey : Dr. K.L.Chowdhury us with their written responses. - An Old Remedy By An Old Hand 21 Thanks Readers. -

Champaign | Fall 2012 Dean's List | Illinois, out of State, International Students

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign | Fall 2012 Dean's List | Illinois, Out of State, International Students STATE / ZIP MIDDLE STUDENT NATION CITY CODE FIRST NAME NAME LAST NAME CLASS COLLEGE MAJOR Illinois Students Agricultural, Consumer & IL Addison Sarah Elizabeth Adams 4 Environmental Sciences Animal Sciences IL Addison Kimberly A Arquines 3 Liberal Arts & Sciences Sociology IL Addison Alex Baciu 1 Liberal Arts & Sciences Chemical Engineering IL Addison Justin T Cruce 2 Engineering Civil Engineering IL Addison Christopher M Gerth 3 Engineering Electrical Engineering IL Addison Cheryl A Kamide 1 Division of General Studies Undeclared IL Addison Timothy P O'Connor 2 Liberal Arts & Sciences Political Science IL Addison Megh J Patel 2 Liberal Arts & Sciences Molecular and Cellular Biology IL Addison Jennifer Marie Rowley 3 Liberal Arts & Sciences English IL Addison Justin T Sumait 1 Division of General Studies Undeclared IL Algonquin Melissa Kelly Blunk 4 Applied Health Sciences Recreation, Sport, and Tourism IL Algonquin Connor Lawrence Booker 1 Liberal Arts & Sciences Biology IL Algonquin Nicholas P Demetriou 2 Engineering Materials Science & Engineering IL Algonquin Anthony J Dombrowski 4 Fine & Applied Arts Architectural Studies IL Algonquin Jessica Ann Gardeck 3 Liberal Arts & Sciences Communication IL Algonquin Jason Mark Gatz 3 Applied Health Sciences Recreation, Sport, and Tourism IL Algonquin Carol Ann Henning 4 Liberal Arts & Sciences Psychology IL Algonquin Michael E Hubner 1 Engineering Mechanical Engineering IL Algonquin -

Modern-Baby-Names.Pdf

All about the best things on Hindu Names. BABY NAMES 2016 INDIAN HINDU BABY NAMES Share on Teweet on FACEBOOK TWITTER www.indianhindubaby.com Indian Hindu Baby Names 2016 www.indianhindubaby.com Table of Contents Baby boy names starting with A ............................................................................................................................... 4 Baby boy names starting with B ............................................................................................................................. 10 Baby boy names starting with C ............................................................................................................................. 12 Baby boy names starting with D ............................................................................................................................. 14 Baby boy names starting with E ............................................................................................................................. 18 Baby boy names starting with F .............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with G ............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with H ............................................................................................................................. 22 Baby boy names starting with I .............................................................................................................................. -

UGC NET PHILOSOPHY SAMPLE THEORY English Version

C SIR NET, GATE, IIT-JAM, UGC NET , TIFR, IISc , JEST , JNU, BHU , ISM , IBPS, CSAT, SLET, NIMCET, CTET UGC NET- PHILOSOPHY SAMPLE THEORY Rta : THE COSMIC ORDER ~ THE INSTITUTION OF YAJNA (SACRIFICE) CONCEPT OF Rna : (DUTY/OBLIGATIONS) THEORIES OF CREATION – CONCEPT OF ATMAN CONCEPT OF BRAHMAN CONCEPT OF KARMA – CONCEPT OF SAMSARA CONCEPT OF MOKSHA For IIT-JAM, JNU, GATE, NET, NIMCET and Other Entrance Exams 1-C-8, Sheela Chowdhary Road, Talwandi, Kota (Raj.) Tel No. 0744-2429714 Web Site www.vpmclasses.com [email protected] Phone: 0744-2429714 Mobile: 9001297111, 9829567114, 9001297243 W ebsite: www.vpmclasses.com E-Mail: vpmclasse [email protected] /[email protected] A ddress: 1-C-8, Sheela Chowdhary Road, SFS, TALWANDI, KOTA , RAJASTHAN, 324005 Page 1 C SIR NET, GATE, IIT-JAM, UGC NET , TIFR, IISc , JEST , JNU, BHU , ISM , IBPS, CSAT, SLET, NIMCET, CTET 1. Rta : The cosmic order 2. The institution of yajn% a (sacrifice) 3. Concept of Rna : (Duty / Obligations) 4. Theories of Creation 5. Concept of Atman 6. Concept of Brahman 7. Concept of Karma 8. Concept of Samsara 9. Concept of Moksha 1. RTA In the Vedic religion 'Rta' is the principle of natural order w hich regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything w ithin it. 'Rta' is properly joined order, rule and truth. In the hy mns of the Vedas 'Rta' is the described as that which is ultimately responsible for the proper functioning of the natural, moral and sacrificial orders. Conceptually, it is closely allied to the injunctions and ordinances thought to uphold it, collectively referred to as 'Dharma', and the action of the individual in relation to those ordinances, referred to as 'Karma' - two terms w hich eventually eclipsed. -

Understanding the Architecture of Hindu Temples: a Philosophical Interpretation A

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Architectural and Environmental Engineering Vol:13, No:12, 2019 Understanding the Architecture of Hindu Temples: A Philosophical Interpretation A. Bandyopadhyay the Upanishads and the Puranas, where the concept of soul Abstract—Vedic philosophy is one of the oldest existing (Atman) was evolved. The souls are a reflection of the philosophies of the world. Started around 6500 BC, in Western Supreme God and hence, in Hinduism there is no concept of Indian subcontinent, the Indus valley Civilizations developed a ‘anti-God’. The divine play (Lila) is the play in which Brahma theology which, gradually developed into a well-established transforms Himself into the world. Lila is a rhythmic play philosophy of beliefs, popularly known as ‘Hindu religion’. In Vedic theology, the abstract concept of God was formulated mostly by close which goes on in endless cycles, the One becoming many and observation of the dynamicity and the recurrence of natural and many becoming One [2, p.220]. “…If we think that the shapes universal phenomena. Through the ages, the philosophy of this and structures, things and events, around us are realities of theology went through various discursions, debates, and questionings nature, instead of realizing that they are concepts of our and the abstract concept of God was, in time, formalized into more measuring and categorizing mind” [2. p.100], then we are in representational forms by the means of various signs and symbols. the midst of the illusions (Maya) of the universe. The soul Often, these symbols were used in more subtle ways in the construction of “sacred” sculptures and structures. -

National Centre for Biological Sciences

Cover Outside Final_452 by 297.pdf 1 16/01/19 10:51 PM National Centre for Biological Sciences Biological for National Centre National Centre for Biological Sciences Tata Institute of Fundamnetal Research Bellary Road, Bangalore 560 065. India. P +91 80 23666 6001/ 02/ 18/ 19 F +91 80 23666 6662 www.ncbs.res.in σ 2 ∂ NCBSLogo — fd 100 ∂t rt 100 fd 200 10-9m 10-5m 10-2m 1m ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 REPORT ANNUAL National Centre for Biological Sciences ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 Cover Inside Final_452 by 297.pdf 1 12/01/19 7:00 PM National Centre for Biological Sciences ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 A cluster of gossamer-winged dragonflies from Dhara Mehrotra’s exhibition “Through Clusters and Networks”, as a part of the TIFR Artist-in-Residence programme PHOTO: DHARA MEHROTRA CONTENTS Director’s Map of Research 4 7 Note Interests Research Theory, Simulation, New Faculty 8 and Modelling of 88 Reports SABARINATHAN RADHAKRISHNAN 8 Biological Systems SHACHI GOSAVI · MUKUND THATTAI · SANDEEP KRISHNA · MADAN RAO · SHASHI THUTUPALLI Biochemistry, Biophysics, 20 and Bioinformatics JAYANT UDGAONKAR · M K MATHEW R SOWDHAMINI · ASWIN SESHASAYEE RANABIR DAS · ARATI RAMESH · ANJANA BADRINARAYANAN · VINOTHKUMAR K R Cellular Organisation 38 and Signalling SUDHIR KRISHNA · SATYAJIT MAYOR · RAGHU PADINJAT · VARADHARAJAN SUNDARAMURTHY 48 Neurobiology UPINDER S BHALLA · SANJAY P SANE · SUMANTRA CHATTARJI · VATSALA THIRUMALAI · HIYAA GHOSH 60 Genetics and Development K VIJAYRAGHAVAN · GAITI HASAN P V SHIVAPRASAD · RAJ LADHER · DIMPLE NOTANI 72 Ecology and Evolution MAHESH -

PAGE-2-OBITUARY.Qxd (Page 2)

MONDAY, APRIL 26, 2021 (PAGE 2) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU UTHALA WITH PROFOUND GRIEF AND SORROW WE INFORM THE SAD DEMISE OF OUR BELOVED SH R.N KAPOOR S/O LT SH WASHESHWAR NATH KAPOOR R/O H.NO 137, SHOPPING CENTRE BAKSHI NAGAR JAMMU ON 23 APRIL 2021. UTHALA WILL BE HELD ON 26TH APRIL (MONDAY) FROM 3 PM TO 4 PM. VENUE - REHARI HARI MANDIR GRIEF STRICKEN DAUGHTER -IN-LAW & SONS MRS. MADHU & DAVINDER KAPOOR REMEMBRANCE MRS. KIRAN & ASHWANI KAPOOR (EX. CHIEF MANAGER CITIZEN C/O BANK) Your life was a blessing, MRS. ANITA & LOKESH KAPOOR BROTHER & BHABHI Your memory a treasure…. MR. SURINDER & KAMLESH KAPOOR You are loved beyond words MR. MOHINDER & USHA KAPOOR And missed beyond measure…. GRANDSON & DAUGHTER-IN-LAW SAMRAT & GARIMA KAPOOR We miss you everyday SHIVANG & RASHMI KAPOOR SH. R.N. KAPOOR MISSED BY ASHISH, TUSHAR Mrs. Subhash Gupta (Wife) GRAND DAUGHTER & SON-IN-LAW 31.10.1929 - 23.4.2021 SMRITI & ABHISHEK KHANNA (Son and DIL) PRIYANKA & RAJESH VERMA Raman Gupta and Shipra Mr. Krishan Lal Gupta HEMANI & VARUN GUPTA (SIL and Daughter) (Retd-Chief Engineer and Member SSRB) SUKRITI & ANKUR ARORA Sachin Sharma and Supriya (1st August 1938- 26th April 2020) YOGYATA & DUSHYANT VERMA Ashwini Gupta and Rashmi (Nephew and DIL) KAPOOR AUTO MOBILES Garvit, Ishan, Isheta, Raghav, Ridhima (Grand children) 10TH DAY/KRIYA/UTHALA Contact-9086052625 With profound grief and sorrow, we informed the sad demise of our 10TH DAY/ SATSANG beloved Mr Uttam Chand Sharma OBITUARY UTHALA (Smailpur Wale) S/o Raja Ram With profound grief and sorrow we regret to With profound grief and sorrow, we With profound grief & sorrow we House No.335 Sector-G, Sainik Colony, inform the sad demise of our beloved Mamaji inform the sad demise of our beloved regret to inform the sad & untimely Jammu who expired on 18-04-2021.