Volume 1: a Dissertation, the Creative Leap: the Science and Philosophy of Creativity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Harron Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

RoRbeRr RtR HaRnHçHTH” Rµ eRåR½RbR± eHTRäR½HTH” R ¸RåR½RbR± R² RèHçRtHaR½HT¡ The One with the https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-with-the-routine-50403300/actors Routine With Friends Like https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/with-friends-like-these...-5780664/actors These... If Lucy Fell https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/if-lucy-fell-1514643/actors A Girl Thing https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-girl-thing-2826031/actors The One with the https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-with-the-apothecary-table-7755097/actors Apothecary Table The One with https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-with-ross%27s-teeth-50403297/actors Ross's Teeth South Kensington https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/south-kensington-3965518/actors The One with https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-with-joey%27s-interview-22907466/actors Joey's Interview Sirens https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sirens-1542458/actors The One Where https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-where-phoebe-runs-50403296/actors Phoebe Runs Jane Eyre https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/jane-eyre-1682593/actors The One Where https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-one-where-ross-got-high-50403298/actors Ross Got High https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/682262/actors Батман и https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%D0%B1%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%BC%D0%B0%D0%BD-%D0%B8- Робин %D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%B8%D0%BD-276523/actors ОглеР´Ð°Ð»Ð¾Ñ‚о е https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%B4%D0%B0%D0%BB%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%BE- -

August 26, 2014 (Series 29: 1) D.W

August 26, 2014 (Series 29: 1) D.W. Griffith, BROKEN BLOSSOMS, OR THE YELLOW MAN AND THE GIRL (1919, 90 minutes) Directed, written and produced by D.W. Griffith Based on a story by Thomas Burke Cinematography by G.W. Bitzer Film Editing by James Smith Lillian Gish ... Lucy - The Girl Richard Barthelmess ... The Yellow Man Donald Crisp ... Battling Burrows D.W. Griffith (director) (b. David Llewelyn Wark Griffith, January 22, 1875 in LaGrange, Kentucky—d. July 23, 1948 (age 73) in Hollywood, Los Angeles, California) won an Honorary Academy Award in 1936. He has 520 director credits, the first of which was a short, The Adventures of Dollie, in 1908, and the last of which was The Struggle in 1931. Some of his other films are 1930 Abraham Lincoln, 1929 Lady of the Pavements, 1928 The Battle of the Sexes, 1928 Drums of Love, 1926 The Sorrows of Satan, 1925 That Royle Girl, 1925 Sally of the Sawdust, 1924 Darkened Vales (Short), 1911 The Squaw's Love (Short), 1911 Isn't Life Wonderful, 1924 America, 1923 The White Rose, 1921 Bobby, the Coward (Short), 1911 The Primal Call (Short), 1911 Orphans of the Storm, 1920 Way Down East, 1920 The Love Enoch Arden: Part II (Short), and 1911 Enoch Arden: Part I Flower, 1920 The Idol Dancer, 1919 The Greatest Question, (Short). 1919 Scarlet Days, 1919 The Mother and the Law, 1919 The Fall In 1908, his first year as a director, he did 49 films, of Babylon, 1919 Broken Blossoms or The Yellow Man and the some of which were 1908 The Feud and the Turkey (Short), 1908 Girl, 1918 The Greatest Thing in Life, 1918 Hearts of the World, A Woman's Way (Short), 1908 The Ingrate (Short), 1908 The 1916 Intolerance: Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages, 1915 Taming of the Shrew (Short), 1908 The Call of the Wild (Short), The Birth of a Nation, 1914 The Escape, 1914 Home, Sweet 1908 Romance of a Jewess (Short), 1908 The Planter's Wife Home, 1914 The Massacre (Short), 1913 The Mistake (Short), (Short), 1908 The Vaquero's Vow (Short), 1908 Ingomar, the and 1912 Grannie. -

Introduction and Methods the Field of Neuroesthetics Is a Recent Marriage

Introduction and Methods The field of neuroesthetics is a recent marriage of the realms of neuroscience and art. The objective of neuroesthetics is to comprehend the perception and subjective experience of art in terms of their neural substrates. In this study, we examined the effect of a number of original pieces of art on the brain of the artist herself and on that of a novice as she experienced the artwork for the first time. This allowed us to compare neural responses not only amongst different visual conditions but also between an expert (i.e. the artist) and a novice. Lia Cook lent her artwork to be used in this study. The pieces, which she believes to have an innate emotional quality, are cotton and rayon textiles. All of the pieces are portraits with a somewhat abstract, pixelated appearance imparted by the medium. In order to better understand the neural effects of the woven facial images, we used several types of control images. These included (i) scrambled woven pieces, or textiles that were controlled for color, contrast, and size but contained no distinct facial forms; and (ii) photographs, which were all photographs of human faces but were printed on heavy paper and lacked the texture and unique visual appearance of the textiles. All of the pieces are 12.5 in. x 18 in. The expert and novice were each scanned with functional MRI while they viewed and touched the tapestries and photographs. The subjects completed 100 trials divided across two functional scans. Each trial lasted a total of 12 s, with jittered intervals of 4 s to 6 s between trials. -

The Right Hemisphere in Esthetic Perception

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 14 October 2011 HUMAN NEUROSCIENCE doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2011.00109 The right hemisphere in esthetic perception Bianca Bromberger, Rebecca Sternschein, Page Widick,William Smith II and Anjan Chatterjee* Department of Neurology, The University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA Edited by: Little about the neuropsychology of art perception and evaluation is known. Most neuropsy- Idan Segev, The Hebrew University of chological approaches to art have focused on art production and have been anecdotal and Jerusalem, Israel qualitative. The field is in desperate need of quantitative methods if it is to advance. Here, Reviewed by: Juliana Yordanova, Bulgarian Academy we combine a quantitative approach to the assessment of art with modern voxel-lesion- of Sciences, Bulgaria symptom-mapping methods to determine brain–behavior relationships in art perception. Bernd Weber, We hypothesized that perception of different attributes of art are likely to be disrupted by Rheinische-Friedrich-Wilhelms damage to different regions of the brain. Twenty participants with right hemisphere dam- Universität, Germany age were given the Assessment of Art Attributes, which is designed to quantify judgments *Correspondence: Anjan Chatterjee, Department of of descriptive attributes of visual art. Each participant rated 24 paintings on 6 conceptual Neurology, The University of attributes (depictive accuracy, abstractness, emotion, symbolism, realism, and animacy) Pennsylvania, 3 West Gates, 3400 and 6 perceptual attributes (depth, color temperature, color saturation, balance, stroke, and Spryce Street, Philadelphia, PA simplicity) and their interest in and preference for these paintings. Deviation scores were 19104, USA. e-mail: [email protected] obtained for each brain-damaged participant for each attribute based on correlations with group average ratings from 30 age-matched healthy participants. -

Files/2014 Women and the Big Picture Report.Pdf>, Accessed 6 September 2018

The neuroscientific uncanny: a filmic investigation of twenty-first century hauntology GENT, Susannah <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0091-2555> Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26099/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26099/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. THE NEUROSCIENTIFIC UNCANNY: A FILMIC INVESTIGATION OF TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY HAUNTOLOGY Susannah Gent A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 Candidate Declaration I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University’s policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acknowledged. 4. The work undertaken towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Neuroesthetics and Healthcare Design

Neuroesthetics and Healthcare Design AUTHOR(S) Upali Nande, PhD; Debajyoti Pati, PhD; and Katie McCurry ABSTRACT: While there is a growing consciousness about the importance of visually pleasing environments in healthcare design, little is known about the key underlying mechanisms that enable aesthetics to play an instrumental role in the caregiving process. Hence it is often one of the first items to be value engineered. Aesthetics has (rightfully) been provided preferential consideration in such pleasure settings such as museums and recreational facilities; but in healthcare settings it is often considered expendable. Should it be? In this paper the authors share evidence that visual stimuli undergo an aesthetic evaluation process in the human brain by default, even when not prompted; that responses to visual stimuli may be immediate and emotional; and that aesthetics can be a source of pleasure, a fundamental perceptual reward that can help mitigate the stress of a healthcare environment. The authors also provide examples of studies that address the role of specific visual elements and visual principles in aesthetic evaluations and emotional responses. Finally, they discuss the implications of these findings for the design of art and architecture in healthcare. FOR COMPLETE ARTICLE PLEASE FOLLOW THE LINK BELOW TO HERD JOURNAL Link: http://www.herdjournal.com/ME2/dirmod.asp?sid=&nm=&type=Abstract&mod=Pu blications%3A%3AArticle&mid=8F3A7027421841978F18BE895F87F791&tier=1 &id=ADECCB0061A6483AB6E92E9379350BCE&Author=&ReturnUrl=dirmod%2 Easp%3Fsid%3D%26nm%3D%26type%3DPublishing%26mod%3DPublications %253A%253AArticle%26mid%3D8F3A7027421841978F18BE895F87F791%26ti er%3D4%26id%3DADECCB0061A6483AB6E92E9379350BCE For a personal copy of this article please contact: t 214.969.3320 Debajyoti Pati at [email protected] www.cadreResearch.org Email: [email protected] CADRE is a nonprofit research and development initiative, supported and funded in part by HKS, Inc. -

The Aesthetic Mind This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Aesthetic Mind Philosophy and Psychology

The Aesthetic Mind This page intentionally left blank The Aesthetic Mind Philosophy and Psychology EDITED BY Elisabeth Schellekens and Peter Goldie 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # the several contributors 2011 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–969151–7 13579108642 Contents List of Figures viii Notes on Contributors ix Introduction 1 Elisabeth Schellekens and Peter Goldie Part I. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO the Monochroidal Artist Or

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Monochroidal Artist or Noctuidae, Nematodes and Glaucomic Vision [Reading the Color of Concrete Comedy in Alphonse Allais’ Album Primo-Avrilesque (1897) through Philosopher Catherine Malabou’s The New Wounded (2012)] A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Theory and Criticism by Emily Verla Bovino Committee in charge: Professor Jack Greenstein, Chair Professor Norman Bryson Professor Sheldon Nodelman Professor Ricardo Dominguez Professor Rae Armantrout 2013 Copyright Emily Verla Bovino, 2013 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Emily Verla Bovino is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2013 iii EPIGRAPH PRÉFACE C’était en 18… (Ça ne nous rajeunit pas, tout cela.) Par un mien oncle, en récompense d’un troisième accessit d’instruction religieuse brillamment enlevé sur de redoutables concurrents, j’eus l’occasion de voir, avant qu’il ne partît pour l’Amérique, enlevé à coups de dollars, le célèbre tableau à la manière noire, intitulé: COMBAT DE NÈGRES DANS UNE CAVE, PENDANT LA NUIT (1) (1) On trouvera plus loin la reproduction de cette admirable toile. Nous la publions avec la permission spéciale des héritiers de l’auteur. L’impression que je ressentis à la vue de ce passionnant chef-d’oeuvre ne saurait relever d’aucune description. Ma destinée m’apparut brusquement en lettres de flammes. --Et mois aussi je serai peintre ! m’écriai-je en français (j’ignorais alors la langue italienne, en laquelle d’ailleurs je n’ai, depuis, fait aucun progrès).(1) Et quand je disais peintre, je m’entendais : je ne voulais pas parler des peintres à la façon dont on les entend les plus généralement, de ridicules artisans qui ont besoin de mille couleurs différentes pour exprimer leurs pénibles conceptions. -

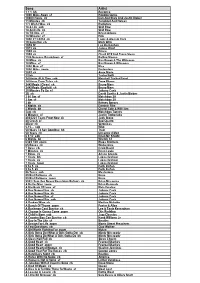

Karaoke List 2021.Xlsx

Song Artist 1 + 1 bh Beyonce 1000 Miles Away sf Hoodoo Gurus 10000 Hours ck Dan And Shay And Justin Bieber 11 Minutes ck Yungblud And Halsey 17 I Wish I Was ck Radiators 18 & Life sgb Skid Row 18 And Life cb Skid Row 18 Till I Die sf Bryan Adams 18 Wheeler sf Pink 1800 273 8255 ck Logic & Alessia Cara 19 Somethin cb Mark Wills 1959 Sf Lee Kernaghan 1973 cb James Blunt 1999 cb Prince 1999 ck Charli XCX And Troye Sivan 19th Nervous Breakdown sf Rolling Stones 20 Miles ck Ray Brown & The Whispers 20 Miles sf Ray Brown & Whispers 2000 Man sf Kiss 2000 Miles zoom Pretenders 2002 ck Anne Marie 22 bh Taylor Swift 24 Hours At A Time sgb Marshall Tucker Band 24 Hours From Tulsa ck Gene Pitney 24K Magic (Clean) ck Bruno Mars 24K Magic (Explicit) ck Bruno Mars 25 Minutes To Go sf Johnny Cash 2U ck David Guetta & Justin Bieber 3 00 Am sf Matchbox 20 3 Am sf Matchbox 20 3 bh Britney Spears 3 Nights ck Dominic Fike 3 Words bh Cheryl Cole & Will I Am 3am cb Matchbox Twenty 4 Minutes sf Justin Timberlake 4003221 Tears From Now ck Judy Stone 48 Crash sf Suzi Quatro 4Ever ck Veronicas 5.15… sgb Who 50 Ways To Say Goodbye bh Train 50 Years ck Uncanny X Men 6 8 12 sgb Brian Mc Knight 6 Words bh Wretch 32 6345 789 zoom Blues Brothers 65 Roses ck Wolverines 7 Days cb Craig David 7 Minutes ck Dean Lewis 7 Rings ck Ariana Grande 7 Years Bh Lukas Graham 7 Years ck Lukas Graham 7 Years zoom Lukas Graham 9 To 5 cb Dolly Parton 9 To 5 kh Dolly Parton 96 Tears sgb Mysterions 99 Red Balloons cb Nena 99 Red Balloons zoom Nena 999% Sure (Ive Never Been Here Before) cb -

Kafka Sends a Missive to His Father

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. Loser Sons Politics and Authority Avita! Ronell Universityof Illinois Press Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield "within" part was no longer locatabl and was working under the new ma1 the most part unrecognizably hande, be fair, Heidegger, too, when his tUI Chapter 4 interiority of self. But I don't see mt Heidegger's motif of the call with may The Good Loser of a lost friend that stays forever on tli and storyline for the call he had to ta Kafka Sends Off a handle its damages is another story I Missive to Father Kafka, for his part, could barely c the determined constraints of childh the writer's pose: one is bent over, wr pared to submit. The so-called "Lett submission, and, if I am not mistake11 "Was wissen die Kinder!" ("What do children know!") their limit of intelligibility wheneve: -Kafka, "Letter" denning birthday, a sexual encountE of manning up, attaining legal majoi "Bittendes Kind" ("Pleading Child") to something like adulthood would l -Schumann, Kinderszenen op. -

RUDOLPH VALENTINO January 1971

-,- -- - OF THE SON SHEIK . --· -- December 1970 -.. , (1926) starring • January 1971 RUDOLPH VALENTINO ... r w ith Vilma Banky, Agnes Ayres, George Fawcett, Kar l Dane • .. • • i 1--...- \1 0 -/1/, , <;1,,,,,/ u/ ~m 11, .. 12/IOJ,1/, 2/11.<. $41 !!X 'ifjl!/1/. , .....- ,,,1.-1' 1 .' ,, ,t / /11 , , . ... S',7.98 ,,20 /1/ ,. Jl',1,11. Ir 111, 2400-_t,' (, 7 //,s • $/1,!!.!!8 "World's .. , . largest selection of things to show" THE ~ EASTIN-PHELAN p, "" CORPORATION I ... .. See paee 7 for territ orial li m1la· 1;on·son Hal Roach Productions. DAVE PORT IOWA 52808 • £ CHAZY HOUSE (,_l928l_, SPOOK Sl'OO.FI:'\G <192 i ) Jean ( n ghf side of the t r acks) ,nvites t he Farina, Joe, Wheeze, and 1! 1 the Gang have a "Gang•: ( wrong side of the tr ack•) l o a party comedy here that 1\ ,deal for HallOWK'n being at her house. 6VI the Gang d~sn't know that a story of gr aveyard~ - c. nd a thriller-diller Papa has f tx cd the house for an April Fool's for all t ·me!t ~ Day party for his fr i ends. S 2~• ~·ar da,c 8rr,-- version, 400 -f eet on 2 • 810 303, Standord Smmt yers or J OO feet ? O 2 , v ozs • Reuulart, s11.9e, Sale reels, 14 ozs, Regularly S1 2 98 , Sale Pnce Sl0.99 , 6o 0 '11 Super 8 vrrs•OQ, dSO -fect,, 2-lb~ .• S l0.99 Regu a rly SlJ 98. Sale Pn ce I Sl2.99 425 -fect I :, Regularly" ~ - t S12 99 400lc0 t on 8 o 289 Standard 8mm ver<lon SO r Sate r eels lJ o,s-. -

THE LIVING YEARS 1 Timbaland

Artist - Track Count mike & the mechanics - THE LIVING YEARS 1 timbaland - nelly furtado - justin - GIVE IT TO ME 1 wet wet wet - LOVE IS ALL AROUND 1 justin timberlake - MY LOVE 1 john mayer - WAITING ON THE WORLD TO CHANGE 1 duran duran - I DON'T WANT YOUR LOVE 1 tom walker - LEAVE A LIGHT ON 1 a fine frenzy - ALMOST LOVER 1 mariah carey - VISION OF LOVE 1 aura dione - SOMETHING FROM NOTHING 1 linkin park - NEW DIVIDE (from Transformers 2) 1 phil collins - GOING BACK 1 keane - SILENCED BY NIGHT 1 sigala - EASY LOVE 1 murray head - ONE NIGHT IN BANGKOK 1 celine dion - ONE HEART 1 reporter milan - STAJERSKA 1 michael jackson - siedah garrett - I JUST CAN'T STOP LOVING YOU 1 martin garrix feat usher - DON'T LOOK DOWN 1 k'naan - WAVIN' FLAG (OFFICIAL 2010 WORLD CUP SONG) 1 jennifer lopez & pitbull - DANCE AGAIN 1 maroon 5 - THIS SUMMER'S GONNA HURT 1 happy mondays - STEP ON 1 abc - THE NIGHT YOU MURDERED LOVE 1 heart - ALL I WANNA DO IS MAKING LOVE 1 huey lewis & the news - STUCK WITH YOU 1 ultravox - VIENNA 1 queen - HAMMER TO FALL 1 stock aitken waterman - ROADBLOCK 1 yazoo - ONLY YOU 1 billy idol - REBEL YELL 1 ashford & simpson - SOLID 1 loverboy - HEAVEN IN YOUR EYES 1 kaoma - LAMBADA 1 david guetta/sia - LET'S LOVE 1 rita ora/gunna - BIG 1 you me at six - ADRENALINE 1 shakira - UNDERNEATH YOUR CLOTHES 1 gwen stefani - LET ME REINTRODUCE MYSELF 1 cado - VSE, KAR JE TAM 1 atomic kitten - WHOLE AGAIN 1 dionne bromfield feat lil twist - FOOLIN 1 macy gray - STILL 1 sixpence none the richer - THERE SHE GOES 1 maraaya - DREVO 1 will young - FRIDAY'S CHILD 1 christina aguilera - WHAT A GIRL WANTS 1 jan plestenjak - lara - SOBA 102 1 barry white - YOU'RE THE FIRST THE LAST MY EVERYTHING 1 parni valjak - PROKLETA NEDELJA 1 pitbull - GIVE ME EVERYTHING TONIGHT 1 the champs - TEQUILA 1 colonia - ZA TVOJE SNENE OCI 1 nick kamen - I PROMISED MYSELF 1 gina g.