An Abstract of the Thesis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story

Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story Edited by Oriana Palusci Alice Munro and the Anatomy of the Short Story Edited by Oriana Palusci This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Oriana Palusci and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0353-4 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0353-3 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Alice Munro’s Short Stories in the Anatomy Theatre Oriana Palusci Section I: The Resonance of Language Chapter One ............................................................................................... 13 Dance of Happy Polysemy: The Reverberations of Alice Munro’s Language Héliane Ventura Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 27 Too Much Curiosity? The Late Fiction of Alice Munro Janice Kulyk Keefer Section II: Story Bricks Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 45 Alice Munro as the Master -

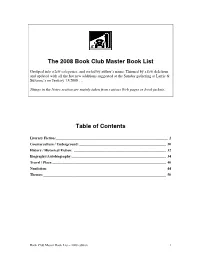

The 2008 Book Club Master Book List Table of Contents

The 2008 Book Club Master Book List Grouped into a few categories, and sorted by author’s name. Thinned by a few deletions and updated with all the hot new additions suggested at the Sunday gathering at Larrie & Suzanne’s on January 13/2008 … Things in the Notes section are mainly taken from various Web pages or book jackets. Table of Contents Literary Fiction:______________________________________________________________ 2 Counterculture / Underground: ________________________________________________ 30 History / Historical Fiction: ___________________________________________________ 32 Biography/Autobiography: ____________________________________________________ 34 Travel / Place:_______________________________________________________________ 40 Nonfiction: _________________________________________________________________ 44 Themes:____________________________________________________________________ 50 Book Club Master Book List – 2008 edition 1 Title / Author Notes Year Literary Fiction: Lucky Jim In Lucky Jim, Amis introduces us to Jim Dixon, a junior lecturer at 2004 (Kingsley Amis) a British college who spends his days fending off the legions of malevolent twits that populate the school. His job is in constant danger, often for good reason. Lucky Jim hits the heights whenever Dixon tries to keep a preposterous situation from spinning out of control, which is every three pages or so. The final example of this--a lecture spewed by a hideously pickled Dixon--is a chapter's worth of comic nirvana. The book is not politically correct (Amis wasn't either), but take it for what it is, and you won't be disappointed. Oryx and Crake Depicts a near-future world that turns from the merely horrible to 2004 (Margaret Atwood) the horrific, from a fool's paradise to a bio-wasteland. Snowman (a man once known as Jimmy) sleeps in a tree and just might be the only human left on our devastated planet. -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Reading Alice Munro, 1973-2013

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2016-02 Reading Alice Munro, 1973-2013 Thacker, Robert University of Calgary Press Thacker, R. "Reading Alice Munro: 1973-2013." University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51092 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca READING ALICE MUNRO, 1973–2013 by Robert Thacker ISBN 978-1-55238-840-2 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Being Gender/Doing Gender, in Alice Munro and Pedro Almadovar

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-25-2017 10:00 AM Being Gender/Doing Gender, in Alice Munro and Pedro Almadovar Bahareh Nadimi Farrokh The Univesity of Western Ontario Supervisor Professor Christine Roulston The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Bahareh Nadimi Farrokh 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Nadimi Farrokh, Bahareh, "Being Gender/Doing Gender, in Alice Munro and Pedro Almadovar" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5000. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5000 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract In this thesis, I compare the short stories, “Boys and Girls” and “The Albanian Virgin”, by Alice Munro, with two films, La Mala Educación and La Piel Que Habito, by Pedro Almodóvar. This comparison analyzes how these authors conceive gender as a doing and a performance, and as culturally constructed rather than biologically determined. My main theoretical framework is Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity as developed in Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. In my first chapter, I compare “Boys and Girls” with La Mala Educación, and in the second chapter, I compare “The Albanian Virgin” with La Piel Que Habito, to illustrate the multiple ways in which gender is constructed according to Munro and Almodóvar. -

Identity, Gender, and Belonging In

UNIVERSITY OF DUBLIN, TRINITY COLLEGE Explorations of “an alien past”: Identity, Gender, and Belonging in the Short Fiction of Mavis Gallant, Alice Munro, and Margaret Atwood A Thesis submitted to the School of English at the University of Dublin, Trinity College, in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Kate Smyth 2019 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. ______________________________ Kate Smyth i Table of Contents Summary .......................................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... iv List of Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................... v Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Part I: Mavis Gallant Chapter 1: “At Home” and “Abroad”: Exile in Mavis Gallant’s Canadian and Paris Stories ................ 28 Chapter 2: “Subversive Possibilities”: -

Table of Contents

Contents About This Volume, Charles E. May vii Career, Life, and Influence On Alice Munro, Charles E. May 3 Biography of Alice Munro, Charles E. May 19 Critical Contexts Alice Munro: Critical Reception, Robert Thacker 29 Doing Her Duty and Writing Her Life: Alice Munro’s Cultural and Historical Context, Timothy McIntyre 52 Seduction and Subjectivity: Psychoanalysis and the Fiction of Alice Munro, Naomi Morgenstern 68 Margaret Atwood and Alice Munro: Writers, Women, Canadians, Carol L. Beran 87 Critical Readings “My Mother’s Laocoon Inkwell”: Lives of Girls and Women and the Classical Past, Medrie Purdham 109 Who does rose Think She is? Acting and Being in The Beggar Maid: Stories of Flo and Rose, David Peck 128 Alice Munro’s The Progress of Love: Free (and) Radical, Mark Levene 142 Friend of My Youth: Alice Munro and the Power of Narrativity, Philip Coleman 160 in Search of the perfect metaphor: The Language of the Short Story and Alice Munro’s “Meneseteung,” J. R. (Tim) Struthers 175 The complex Tangle of Secrets in Alice munro’s Open Secrets, Michael Toolan 195 The houses That Alice munro Built: The community of The Love of a Good Woman, Jeff Birkenstein 212 honest Tricks: Surrogate Authors in Alice munro’s Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage, David Crouse 228 Narrative, Memory, and Contingency in Alice Munro’s Runaway, Michael Trussler 242 v Alice_Munro.indd 5 9/17/2012 9:01:50 AM “Secretly Devoted to Nature”: Place Sense in Alice Munro’s The View from Castle Rock, Caitlin Charman 259 “Age Could Be Her Ally”: Late Style in Alice Munro’s Too Much Happiness, Ailsa Cox 276 Resources Chronology of Alice Munro’s Life 293 Works by Alice Munro 296 Bibliography 297 About the Editor 301 Contributors 303 vi Critical Insights Alice_Munro.indd 6 9/17/2012 9:01:50 AM. -

The Love of a Good Woman” Ulrica Skagert University of Kristianstad

Things within Things Possible Readings of Alice Munro’s “The Love of a Good Woman” Ulrica Skagert University of Kristianstad Abstract: Alice Munro’s “The Love of a Good Woman” is perhaps one of the most important stories in her œuvre in terms of how it accentuates the motivation for the Nobel Prize of Literature: “master of the contemporary short story.” The story was first published in The New Yorker in December 1996, and over 70 pages long it pushes every rule of what it means to be categorised as short fiction. Early critic of the genre, Edgar Allan Poe distinguished short fiction as an extremely focused attention to plot, properly defined as that to which “no part can be displaced wit- hout ruin to the whole”. Part of Munro’s art is that of stitching seemingly disparate narrative threads together and still leaving the reader with a sense of complete- ness. The story’s publication in The New Yorker included a subtitle that is not part of its appearing in the two-year-later collection. The subtitle, “a murder, a mystery, a romance,” is interesting in how it is suggestive for possible interpretations and the story’s play with genres. In a discussion of critical readings of Munro’s story, I propose that the story’s resonation of significance lies in its daring composition of narrative threads where depths of meaning keep occurring depending on what aspects one is focusing on for the moment. Further, I suggest that a sense of completion is created in tone and paralleling of imagery. -

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018 www.scotiabankgillerprize.ca # The Boys in the Trees, Mary Swan – 2008 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, Mona Awad - 2016 Brother, David Chariandy – 2017 419, Will Ferguson - 2012 Burridge Unbound, Alan Cumyn – 2000 By Gaslight, Steven Price – 2016 A A Beauty, Connie Gault – 2015 C A Complicated Kindness, Miriam Toews – 2004 Casino and Other Stories, Bonnie Burnard – 1994 A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry – 1995 Cataract City, Craig Davidson – 2013 The Age of Longing, Richard B. Wright – 1995 The Cat’s Table, Michael Ondaatje – 2011 A Good House, Bonnie Burnard – 1999 Caught, Lisa Moore – 2013 A Good Man, Guy Vanderhaeghe – 2011 The Cellist of Sarajevo, Steven Galloway – 2008 Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood – 1996 Cereus Blooms at Night, Shani Mootoo – 1997 Alligator, Lisa Moore – 2005 Childhood, André Alexis – 1998 All My Puny Sorrows, Miriam Toews – 2014 Cities of Refuge, Michael Helm – 2010 All That Matters, Wayson Choy – 2004 Clara Callan, Richard B. Wright – 2001 All True Not a Lie in it, Alix Hawley – 2015 Close to Hugh, Mariana Endicott - 2015 American Innovations, Rivka Galchen – 2014 Cockroach, Rawi Hage – 2008 Am I Disturbing You?, Anne Hébert, translated by The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Wayne Johnston – Sheila Fischman – 1999 1998 Anil’s Ghost, Michael Ondaatje – 2000 The Colour of Lightning, Paulette Jiles – 2009 Annabel, Kathleen Winter – 2010 Conceit, Mary Novik – 2007 An Ocean of Minutes, Thea Lim – 2018 Confidence, Russell Smith – 2015 The Antagonist, Lynn Coady – 2011 Cool Water, Dianne Warren – 2010 The Architects Are Here, Michael Winter – 2007 The Crooked Maid, Dan Vyleta – 2013 A Recipe for Bees, Gail Anderson-Dargatz – 1998 The Cure for Death by Lightning, Gail Arvida, Samuel Archibald, translated by Donald Anderson-Dargatz – 1996 Winkler – 2015 Curiosity, Joan Thomas – 2010 A Secret Between Us, Daniel Poliquin, translated by The Custodian of Paradise, Wayne Johnston – 2006 Donald Winkler – 2007 The Assassin’s Song, M.G. -

Reading Alice Munro, 1973-2013

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2016-02 Reading Alice Munro, 1973-2013 Thacker, Robert University of Calgary Press Thacker, R. "Reading Alice Munro: 1973-2013." University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51092 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca READING ALICE MUNRO, 1973–2013 by Robert Thacker ISBN 978-1-55238-840-2 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

Courting Johanna: Adapting Alice Munro for the Stage

Shelley Scott University of Lethbridge Courting Johanna: Adapting Alice Munro for the Stage In this paper I will consider Alice Munro’s story “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage,” which was published in 2001 in a collection of the same name, in the form of its adaption as a play by Marcia Johnson. The play, Courting Johanna, premiered at the Blyth Theatre Festival in 2008 and was published the next year. In considering one of Munro’s stories as a play, I will be joining many other critics in asking how Alice Munro achieves her particular affect, but I will be approaching the question from a transmedia perspective. By asking how this adaptation works on the stage, I will be asking questions about the nature of theatrical representation, the feminism fundamental to Munro’s world view, and whether we can, perhaps paradoxically, understand Munro’s story-writing genius by looking at it in the mirror of the theatre. In my case, I am able to draw on the experience of directing a student production of Courting Johanna at the University of Lethbridge in February 2014 - the perspective of personally bringing the play from page to stage. Alice Munro’s stories have inspired a select number of Canadian film and television adaptations, most famously the 2006 film Away From Her, which won director Sarah Polley a Genie Award and an Oscar nomination for her adapted screenplay. The short story cycle Lives of Girls and Women was adapted for CBC television in 1994, and “Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage” premiered at the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival as Hateship Loveship, but has not yet had theatrical release. -

Alice Munro, at Home and Abroad: How the Nobel Prize in Literature Affects Book Sales

BNC RESEARCH Alice Munro, At Home And Abroad: How The Nobel Prize In Literature Affects Book Sales + 12.2013 PREPARED BY BOOKNET CANADA STAFF Alice Munro, At Home And Abroad: How The Nobel Prize In Literature Affects Book Sales December 2013 ALICE MUNRO, AT HOME AND ABROAD: HOW THE NOBEL PRIZE IN LITERATURE AFFECTS BOOK SALES With publications dating back to 1968, Alice Munro has long been a Canadian literary sweetheart. Throughout her career she has been no stranger to literary awards; she’s taken home the Governor General’s Literary Award (1968, 1978, 1986), the Booker (1980), the Man Booker (2009), and the Giller Prize (1998, 2004), among many others. On October 10, 2013, Canadians were elated to hear that Alice Munro had won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Since the annual award was founded in 1901, it has been awarded to 110 Nobel Laureates, but Munro is the first Canadian—and the 13th woman—ever to win. In order to help publishers ensure they have enough books to meet demand if one of their titles wins an award, BookNet Canada compiles annual literary award studies examining the sales trends in Canada for shortlisted and winning titles. So as soon as the Munro win was announced, the wheels at BookNet started turning. What happens when a Canadian author receives the Nobel Prize in Literature? How much will the sales of their books increase in Canada? And will their sales also increase internationally? To answer these questions, BookNet Canada has joined forces with Nielsen Book to analyze Canadian and international sales data for Alice Munro’s titles.